682

MRS BULLETIN

•

VOLUME 37

•

JULY 2012

•

www.mrs.org/bulletin

© 2012 Materials Research Society

Introduction

Now, perhaps more than at any previous time, there is widespread

appreciation of the urgent need for new functional materials and

the critical role they play in matters of great importance to energy,

the environment, sustainability, and the economy. A number of

recent panel reports in the United States, including those coordi-

nated by the National Research Council (NRC),

1

the Department

of Energy,

2

and the Offi ce of Science and Technology Policy of

the National Science and Technology Council,

3

have emphasized

the importance of new, enabling materials in the economy and

the need to critically examine the current status and future pros-

pects. With support and encouragement from the US National

Science Foundation, the authors of this contribution organized

a workshop in 2011 on the theme of “Materials by Design”

( http :// www . mbd . mrl . ucsb . edu ). Broadly defi ned, “Materials by

Design” has the goal of achieving desired properties in materials

through appropriate tuning of composition, structure, and architec-

ture, which enables a given application. The expertise represented

at the workshop ranged from solid-state chemistry, to organic,

hybrid, nano, and liquid crystalline materials, to crystal growth,

condensed matter experiment, and included both pencil-and-paper

and computational theory. The questions of most interest to the

participants were: How does one go about increasing the effi cien-

cies in the process of new materials development, and concurrently

to achieve this end, how does one make better, more effective use

of theory and computation?

While the workshop participants were primarily based in the

United States, we believe the fi ndings presented have global rel-

evance. Indeed, the integrated approaches to “Materials by Design”

lend themselves very well to international collaborations.

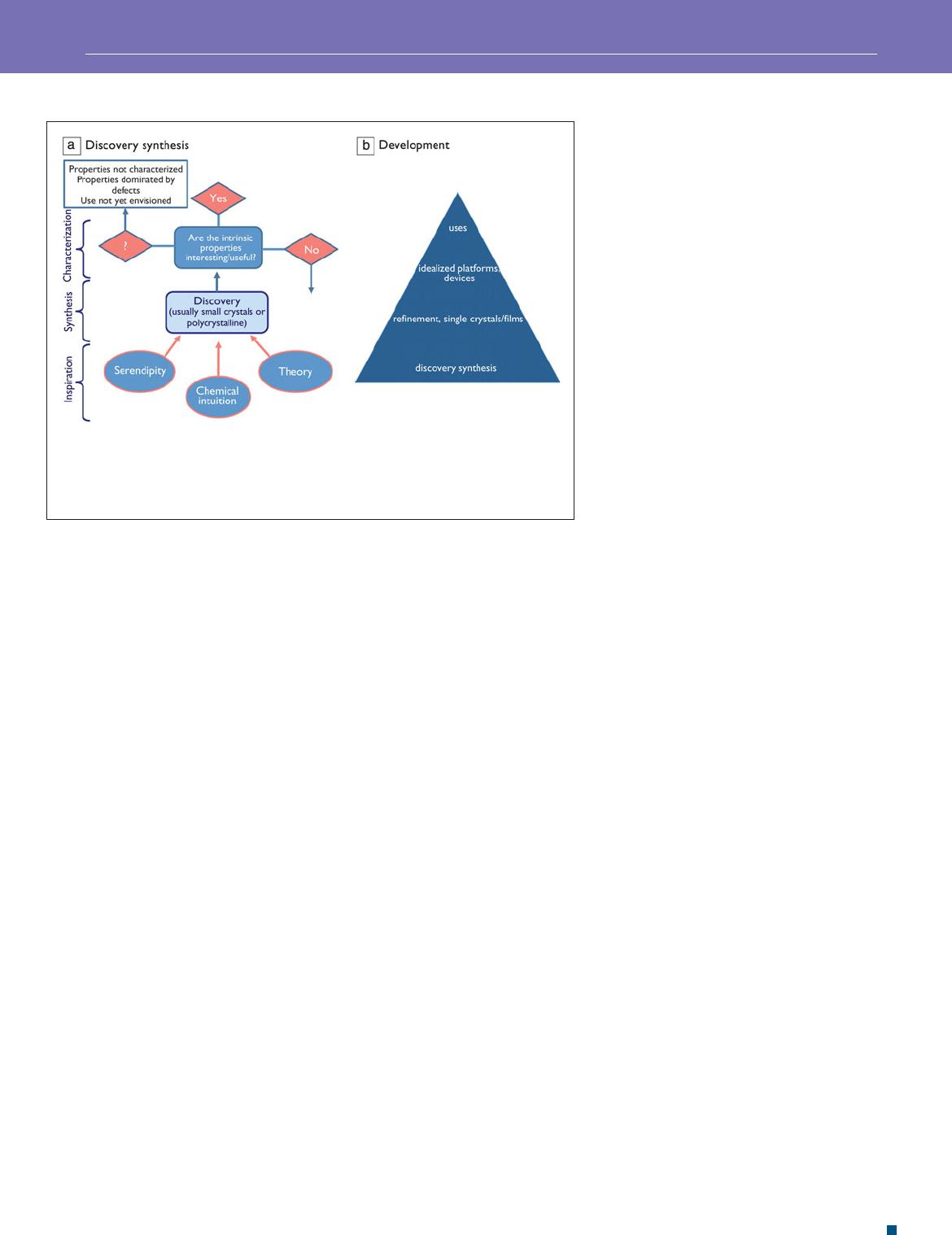

As a starting point, we consider a typical fl owchart

( Figure 1 a) depiction of the process of envisioning/designing

and preparing a new material for a particular application, also

sometimes referred to as discovery synthesis. Theory and chem-

ical intuition—often in conjunction with the known literature—

can combine to suggest a target material, but in many cases,

the material produced is not that intended, so the role of

serendipity cannot be overlooked. The synthesis of the material,

Advances in the development and

growth of functional materials: Toward

the paradigm of materials by design

Ram Seshadri , Stephanie L. Brock , Arthur Ramirez ,

M.A. Subramanian , and Mark E. Thompson

Research in functional materials is frequently driven by a desire to make informed choices

in the quest for better, more effective materials. A great deal of recent attention has been

focused on the modalities of how such informed choices can themselves be made in a better,

more effective manner. The examples presented here examine some of these modalities,

emphasizing the nexus between new synthesis, computational design and analysis, growth

in high purity forms, and nally, end-use in terms of either application or of signi cant property

measurement. The illustrations, many drawn from the recent literature, commence with the

role that theory has played, both in property prediction and concomitant materials selection,

in the areas of multiferroics and topological insulators. The importance of materials quality is

emphasized, using examples from observation of the fractional Quantum Hall Effect, where

new science has emerged as a result of improved materials. In the area of organic electronics,

prospects for advancing the eld are suggested, as are future directions in nanoscience.

While the examples chosen here point to developments that require a highly collaborative

“systems” approach to materials, the role that serendipity plays is not ignored.

DOI: 10.1557/mrs.2012.147

ADVANCES IN FUNCTIONAL MATERIALS: TOWARD THE PARADIGM OF MATERIALS BY DESIGN

683

MRS BULLETIN

•

VOLUME 37

•

JULY 2012

•

www.mrs.org/bulletin

often as small crystals or in polycrystalline form, followed by

property measurements, can result in a return to searching for other

materials or to the next steps of developing the material. The devel-

opment process, from small and potentially defective crystals to

samples that actually display the desired property, can be long and

arduous, but has a potentially huge payoff. In the characterization

stage, the properties could be other than that originally envisioned,

potentially leading to new applications. Some of the illustrative

examples, described later, are representative of various aspects of

such fl owcharts. The steps involved in discovery synthesis shown

in Figure 1a in turn lead to the generation of the broad class of

materials that form the base of the materials development pyra-

mid, displayed in Figure 1b . This scheme, fi rst described by Brian

Sales at Oak Ridge National Laboratory (this version is from John

Mitchell, Argonne National Laboratory), refl ects on the very large

number of samples of functional materials that normally require

screening before a select few are then chosen for refi ning in the

form of better samples and high quality thin fi lms. These then have

to be appropriately incorporated into the fi nal device in order for

the material to fi nd use.

The two panels of Figure 1 suggest a linear progression of

materials development, from conception to application. A key

recommendation of the Materials Genome Initiative for Global

Competitiveness

2

refl ects some of the intrinsic drawbacks of

such a linear progression and points to how the different stages

in the progression, when addressed by engineering or scientifi c

teams at different institutions, results in “opportunities for feed-

back between stages that could accelerate the full continuum.”

The initiative calls for greater transparency in the way that data

can be shared and potentially “mined” such that at every step

of the development process, all players can access the knowl-

edge that informs every step, including their own. Concerning

the materials pyramid displayed in Figure 1b , the NRC report

1

mentioned previously points to the weakened

status of efforts in the United States that are

focused on crystal growth, including the growth

of high quality thin fi lms, particularly follow-

ing the closure of some large industrial labs

that were able to focus on long-term materials

development. The specifi c role of one of these—

Bell Labs—in enabling many new technologies,

themselves frequently the result of advances in

materials research, has been recently described.

4

A question of continuing concern in the con-

text of the United States is whether research in

universities and National Laboratories can fi ll

the lacuna left by the closure of large industrial

labs that were active in the arena of materials

improvement and development.

The purpose of this article is to use illustra-

tive examples in the creation and deployment of

functional materials, both organic and inorganic,

to make a number of points regarding the cre-

ative lifespan of materials, from birth to utility.

Examples presented here emphasize the kind of

intellectual and experimental resources that are required at the

different stages. Suggestions for the advancement of the different

domains of materials research are made, when appropriate. The

takeaway message of this article is that the advancement of new

functional materials science follows many different paths, but all

of these paths benefi t from interdisciplinary collaborations and,

oftentimes, an openness to interesting surprises.

The development of GaN lighting

It is interesting to contemplate the emergence of effi cient GaN

light-emitting devices that allowed effi cient blue and green light

sources to become a reality. GaN is not a new material. First pre-

pared in 1932,

5

the structure was solved by Juza and Hahn in 1938.

6

According to the authoritative history by Schubert,

7

researchers

at the RCA labs recognized the potential for a GaN-based blue

emitter in the 1960s when they made the fi rst metal-insulator-

semiconductor blue emitter. Effi cient emission, however, had to

await p -type GaN and the formation of p-n junctions, leading to

the development of “candela” class blue emitters

8

and, eventually

in 1996, the blue laser diode.

9

It is interesting to note the break-

throughs did not necessarily come from large, well-funded labs, but

instead were the result of a few passionate and resourceful people

focusing their efforts on an important problem. The proliferation

of white solid-state lighting based on nitride emitters, with its

promise of clean, reliable, and effi cient lighting, suggests that

even materials that are potentially very impactful need not be the

product of a vast and concerted effort. This is not to suggest that

such a focused effort would not pay dividends.

Computational inspiration for new

multiferroics: The example of strained EuTiO

3

Magnetoelectric multiferroics are compounds that can display

concurrent and coupled magnetic and polar order, and, in the

Figure 1. Schematic owchart depicting the process of (a) discovery synthesis of new

materials, leading to the formation of the base of the (b) materials pyramid. Panel (a)

courtesy of P.W. Woodward, Ohio State University, and panel (b) courtesy of John Mitchell,

Argonne National Laboratory, modi ed from a scheme originally suggested by Brian Sales,

Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

ADVANCES IN FUNCTIONAL MATERIALS: TOWARD THE PARADIGM OF MATERIALS BY DESIGN

684

MRS BULLETIN

•

VOLUME 37

•

JULY 2012

•

www.mrs.org/bulletin

best possible case, these orders are respectively ferromagnetism

and ferroelectricity.

10

,

11

This is an area where density functional

calculations have played a particularly important role in unrav-

eling the different processes and mechanisms that allow for the

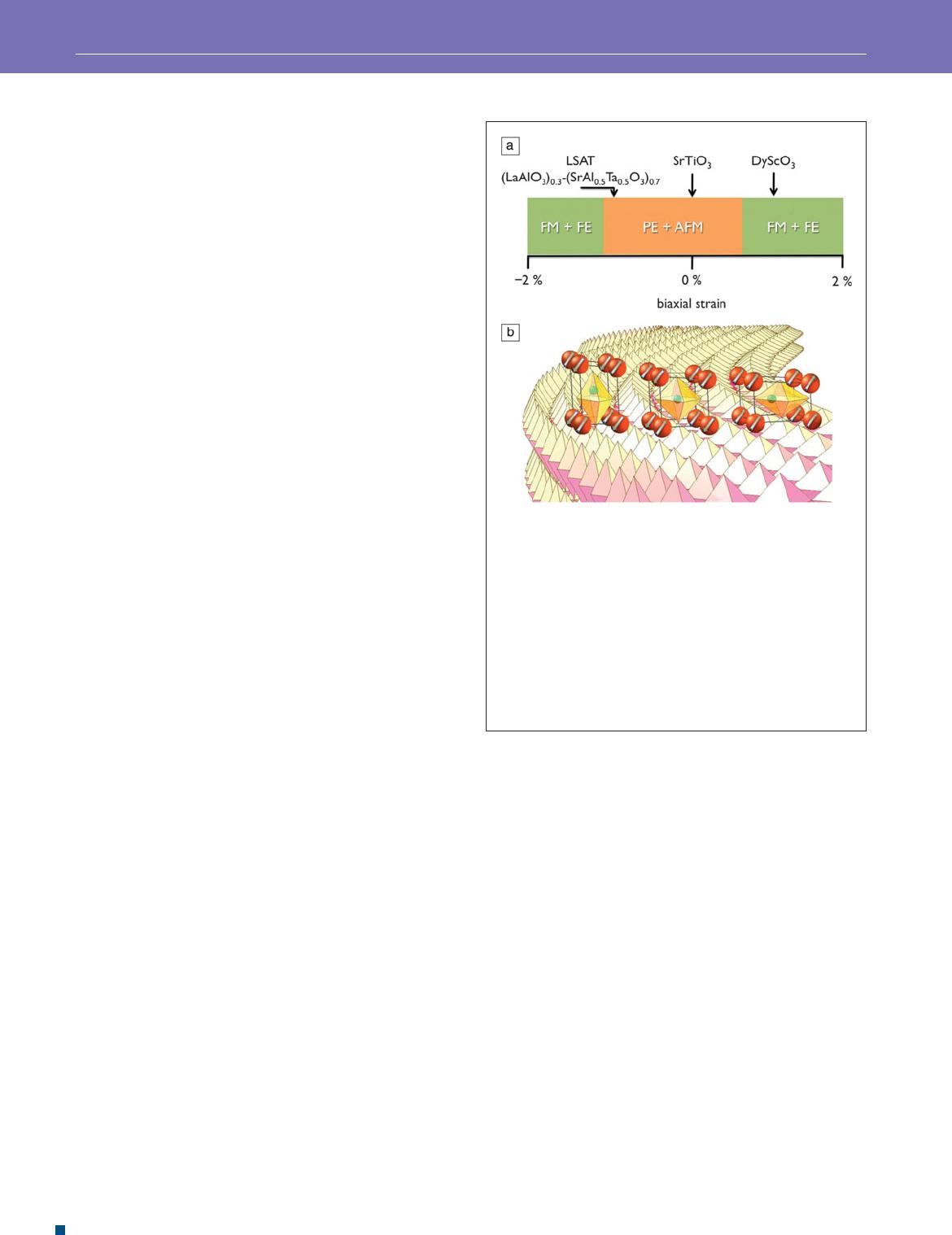

observation of these multiply ordered ground states. In one such

example using density functional modeling, a mechanism for

stabilizing a multiferroic phase in a material that is otherwise

antiferromagnetic and paraelectric in the bulk was identifi ed.

12

It was suggested that such control could be obtained through

tuning the competition between the different magnetic and

structural instabilities in the compound. The control parameter was

biaxial strain, which when applied to the material, EuTiO

3

,

was proposed to give rise to a multiferroic fi gure-of-merit that was

about a thousand-fold greater than the best previously known

material. The original theoretical study chose to focus only on

the application of compressive strain. The critical strain value

necessary to drive the system into the multiferroic phase was

about 1.1%. It was then suggested from the experimental side

that there are many more substrates that would result in tensile

strain being induced when EuTiO

3

is grown epitaxially on them.

As a result of this suggestion, the full strain phase diagram

of EuTiO

3

was obtained computationally, and it was found

that signifi cantly less tensile strain, about 0.6%, is required to

drive the compound into a multiferroic phase.

13

The smaller

strain required also allows thicker and higher quality fi lms to

be grown. As described in a recent letter,

13

strained EuTiO

3

was grown on a variety of substrates and characterized by a

team of collaborators from around the world, confi rming the

suggestions from computation. Figure 2 displays the computed

property phase diagram of strained EuTiO

3

as a function of

the strain and schemes of the resulting crystal and magnetic

structures. It should be noted that in these AB O

3

perovskites,

magnetism arises on the A site and polar behavior from the

displacement of the B ions.

The key role of formal theory: Development of

topological insulators

The discovery of three-dimensional topological insulators

provides an example of the interplay between different kinds

of theory and experiment and, in particular, emphasizes that for-

mal theory can play a key role in predicting and understanding

new phenomena. Materials-specifi c modeling, as embodied in

density functional electronic structure theory, can then play a

collaborating role in suggesting real systems where certain phe-

nomena may be observed. Interestingly, at a time when much

of condensed matter physics is focused on correlated electronic

phenomena, the understanding of topological insulators largely

requires simple, single-particle theories.

14

,

15

Topological insula-

tors are materials that are insulating in bulk but have protected

metallic surface states as a result of spin-orbit coupling. Formal

theoretical work, motivated by seeking generalizations of the

quantum Hall and quantum spin Hall effects in two-dimensional

systems, showed that similar mathematical structures (topologi-

cal invariants) could, in principle, be generated by spin-orbit

coupling, leading to new phases, dubbed topological insulators.

Several candidate materials were then proposed based on heu-

ristic arguments and fi rst-principles calculations, contributing

to the experimental discovery of the characteristic massless

surface state and spin-momentum locking in BiSb alloys and

Bi

2

Se

3

. This is an area that has been recently reviewed, for

example, in References 14 and 15. Following the initial role of

formal theory, more materials-specifi c approaches have come

into play, and a number of suggestions for interesting materials

classes have been put forth, such as the suggestion that the half-

Heusler XYZ structure type, comprising three interpenetrating

fcc sublattices of (usually) two metals, X and Y , and a main

group element, Z , is a rich playing fi eld for the area of tunable,

multifunctional topological insulators.

16

,

17

Better samples lead to new science: The

example of GaAs heterostructures

The science of topological insulators, referred to in the previous

section, is in fact closely inspired by studies on the fractional

quantized Hall effect. Single-crystal GaAs fi lms are a natural

extension of the deep experience of the scientifi c and techno-

logical community with single-crystal Si. A search by physi-

cists for a more perfect semiconductor-insulator interface than

realizable in Si-SiO

2

led to the development of the GaAs-AlAs

Figure 2. Suggestions from rst-principles electronic

structure calculations that perovskite EuTiO

3

can, under

both tensile and compressive strains, switch its ground state

from being paraelectric (PE) and antiferromagnetic (AFM)

to being ferroelectric (FE) and ferromagnetic (FM) have now

been experimentally realized. The upper panel (a) shows the

computed dependence of the ground state on strain, and the

lower panel (b) displays schemes of different magnetic and

polar orderings in the perovskite structure corresponding to the

regimes in (a). Orange atoms at the corners of the perovskite

cell are Eu

2+

and carry spin, indicated by arrows. TiO

6

octahedra

are indicated with Ti

4+

shown as green spheres at the centers

of the octahedra. Figure courtesy of Craig Fennie, Cornell

University.

ADVANCES IN FUNCTIONAL MATERIALS: TOWARD THE PARADIGM OF MATERIALS BY DESIGN

685

MRS BULLETIN

•

VOLUME 37

•

JULY 2012

•

www.mrs.org/bulletin

system, in which both the conducting GaAs and the insulating

AlAs are incorporated in the same single crystal, usually in

an alternating fashion. Using advances made in techniques

to epitaxially grow single-crystal fi lms, near-perfect crystal

interfaces can be produced. In these fi lms, the absence of a

disordered electronic interface gives the freedom to reduce the

conducting channel thickness to about 10 nm, which is near the

quantum size of conduction electrons in GaAs. The electrons

can thus move in the plane of the GaAs channel but not out of

the GaAs layer because of the AlAs insulating barriers. Thus,

a material that is effectively two-dimensional can be created.

The unusual nature of two-dimensional electrons can be

probed in Hall-effect experiments. For metal samples, such

as the gold leaf foil used originally by Edwin Hall in 1879, the

resistance grows smoothly and linearly with an increase in

the magnetic fi eld B. However, for high-purity semiconducting

systems at low temperatures, the Hall resistance shows a series

of discrete plateau steps that cannot be understood without

considering the quantum properties of the conducting electrons.

Even more striking is that the numerical values of the various

resistance plateaus are given by exact ratios of fundamental

physical constants, at values of h /( ν e

2

), where h is Planck’s

constant, e is the charge on the electron, and ν is the fi lling fac-

tor, which in the Quantum Hall Effect takes on integer values.

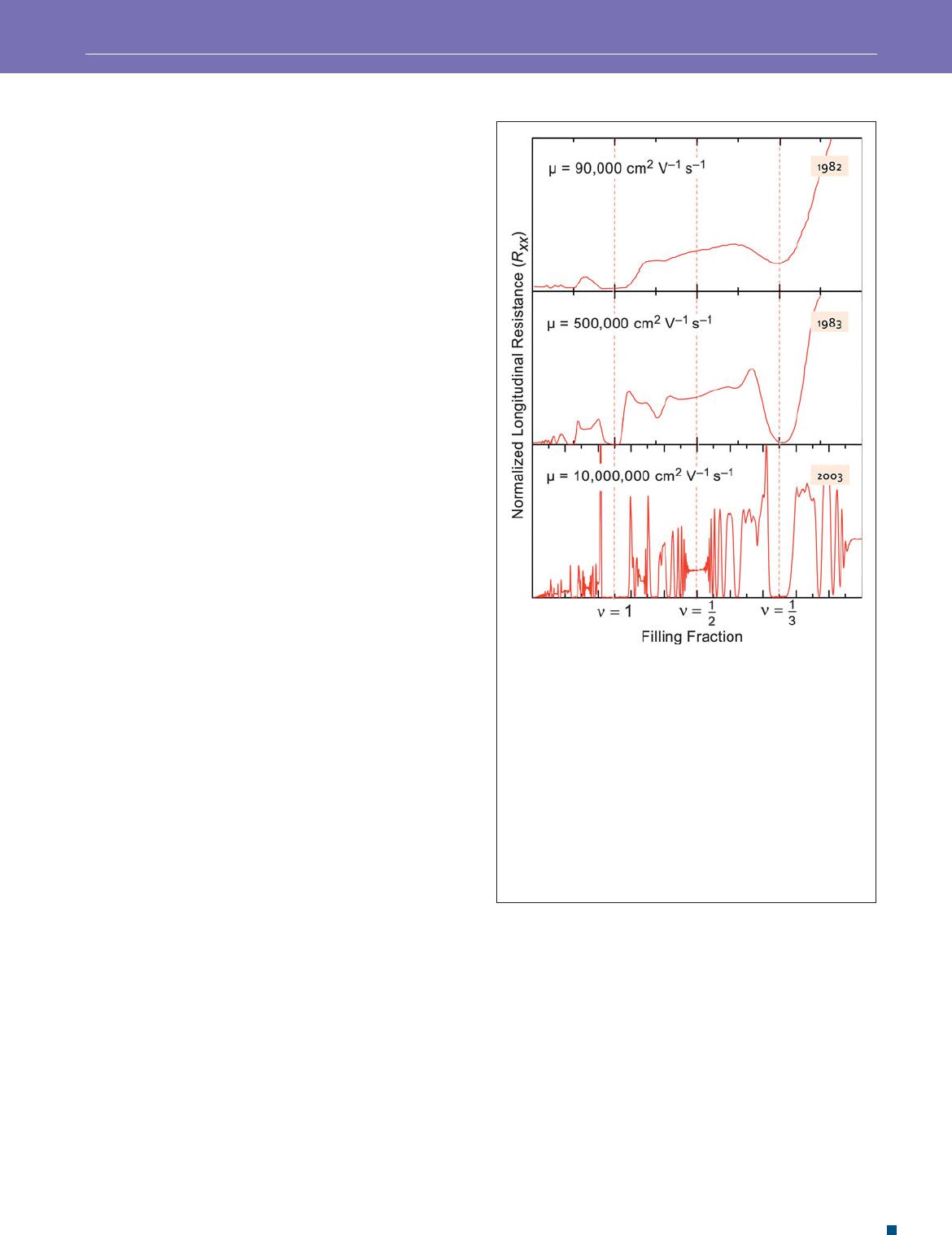

The realization that increasing the crystalline quality in the

two-dimensional region could lead to a more robust quantum

Hall effect led to experiments using the potentially higher-

quality GaAs-AlGaAs interface. In 1982, Stormer et al.

18

published a truly novel experimental result shown in the top

panel of Figure 3 . Not only did they see the integer effect,

but they also saw a clear plateau at ν = 1/3, in other words, a

fractional rather than an integer value. They had discovered

the fractional quantum Hall effect. This discovery in GaAs

launched an effort to further improve the quality of the GaAs

crystal samples. The panels in Figure 3 show the increasing

richness of observed fractional states as the sample quality

(measured by the electron mobility μ ) has improved over the

years. For a sample of mobility 5 × 10

5

cm

2

V

−1

s

−1

,

19

one sees that

the states at 1/3 and 2/3 are joined by other states, and in the

bottom-most trace where the mobility is of the order of 10

7

cm

2

V

−1

s

−1

,

20

these states are joined by a hierarchy of states, all hav-

ing odd denominators and all organized around an absent state

at ν = 1/2. These experiments provide dramatic evidence for a

series of new emergent particles called composite fermions.

21

Better samples lead to better understanding:

The example of SrTiO

3

and conducting polymers

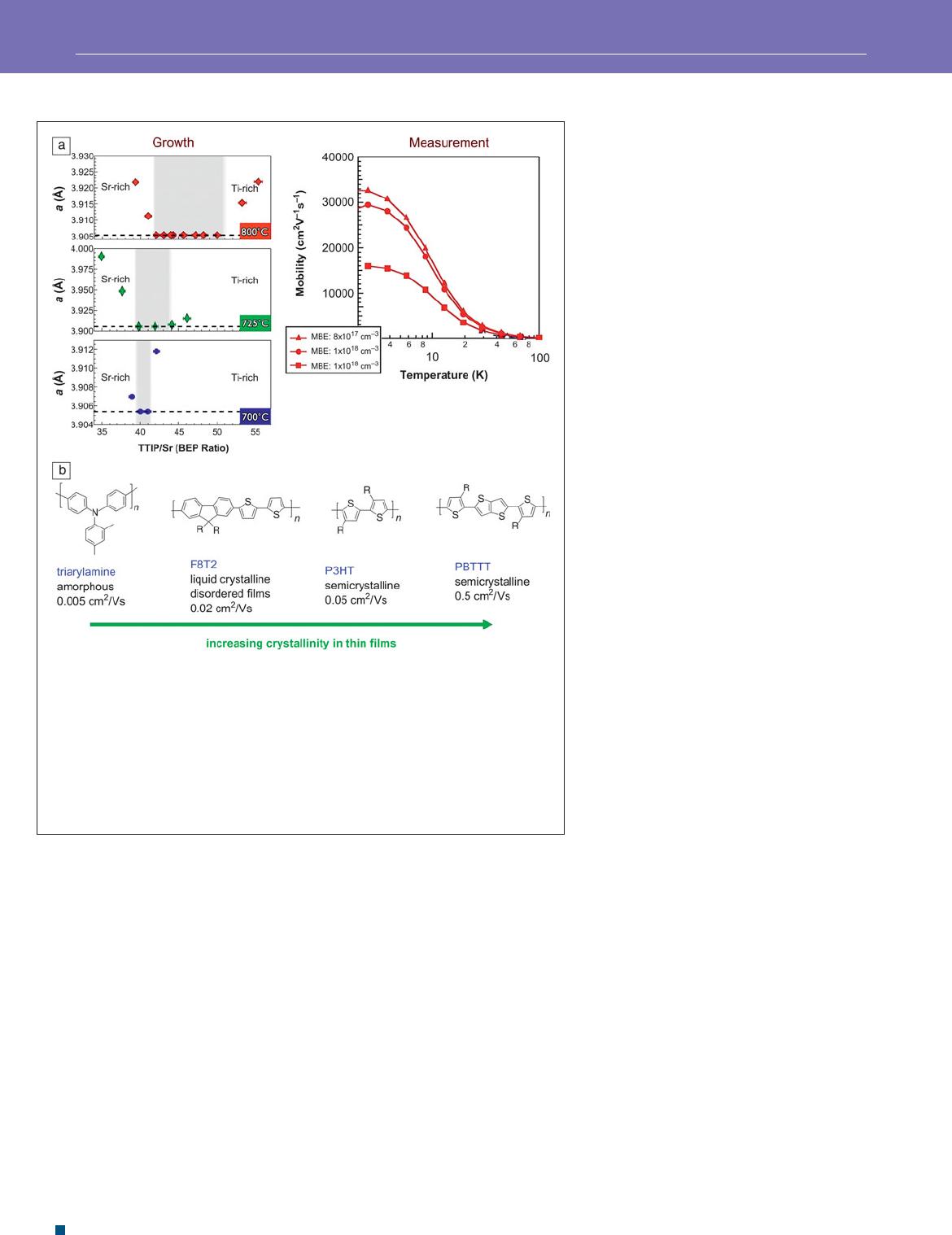

One of the lessons learned from GaAs is the importance of

sample quality. This has recently become of particular relevance

in the examination of thin fi lms of high quality oxides and their

heterointerfaces that have so captured the imagination with the

possibility of oxide electronics.

22

The question of whether the

kinds of growth processes that are applicable in the prepara-

tion of high quality GaAs fi lms can be transferred to oxide thin

fi lms has recently been addressed.

23

Molecular beam epitaxy

of SrTiO

3

uses a molecular beam source for Sr and titanium

tetraisopropoxide (TTIP) for the Ti source. A key to growing

high quality fi lms is to work under conditions, also frequently

referred to as growth windows, which naturally lead to the cor-

rect stoichiometry of the phase being formed. In SrTiO

3

, this

is appropriately probed using the unit cell parameter. SrTiO

3

is an optimally bonded band semiconductor, and any change

from the “1-1-3” stoichiometry results in underbonding, as seen

from an expansion of the lattice. The growth windows therefore

correspond to regions where the lattice parameter displays a

plateau as a function of varying the ratio of starting materials,

and this plateau is a minimum. This is displayed in the left panel

of Figure 4 a.

23

The use of such a growth window has resulted

in complex oxide fi lms with unprecedented mobilities,

24

as seen

Figure 3. Better samples lead to new science: Longitudinal

resistance, R

xx

, for three different two-dimensional electron gas

samples as a function of the magnetic eld, as expressed in

terms of lling factor ν = nh / eB, where n is the electron density,

h is the Planck constant, e is the charge on an electron, and B

is the magnetic eld. The samples are formed at the interface of

crystalline GaAs and AlGaAs grown by molecular beam epitaxy.

The samples are distinguished by different values of the mobility,

μ , that have increased systematically over time. The upper frame

shows the rst report, in 1982, of fractional lling at ν = 1/3 and

T = 0.48 K.

18

The middle frame shows new states at ν = 1/3,

2/5, 2/3 achieved in higher mobility samples at T = 0.55 K.

19

The

bottom frame shows data from a typical modern high mobility

sample at T = 0.35 K.

20

This sample exhibits self similarity

between the ν = 0 and ν = 1/2 states that is the basis for the

“composite fermion” description of electronic states.

ADVANCES IN FUNCTIONAL MATERIALS: TOWARD THE PARADIGM OF MATERIALS BY DESIGN

686

MRS BULLETIN

•

VOLUME 37

•

JULY 2012

•

www.mrs.org/bulletin

in the right panel of Figure 4a . Complex oxides are fascinating

materials because of the range of physical phenomena that they

can display and, in bringing semiconducting oxides into this

high-mobility regime, what seems to be one of the last materials

frontiers is being traversed.

In the area of organic electronics, discussed in the next

section, the extent of delocalization is important in design-

ing the electronic properties of molecules. In addition, it is

also critical to think of the morphology and, specifi cally,

the extent of crystallinity in the case of evaporated fi lms. In

Figure 4b , the mobility, measured using fi eld-effect transistor

geometry, of some amorphous, liquid crystalline, and semi-

crystalline conjugated polymers are displayed. A clear trend

is observed that with increasing crystallinity, the mobil-

ity increases by two orders of magnitude. The availability

of organic polymer fi lms displaying increasingly higher

mobility and potentially band-like transport enables better

understanding and even modeling of these

highly complex systems. Comparing organics

with the oxides, and the more classical main

group semiconductors referred to previously,

it becomes evident that although the observed

phenomena can differ by many orders of

magnitude, some of the goals (e.g., the fab-

rication of transistors) in the very divergent

materials classes can be similar.

The organic advance of

optoelectronics: Light-emitters,

photovoltaics, and transistors

Organic materials hold a great deal of promise

for applications in electronic and optoelectronic

devices. Both molecular and polymeric materi-

als have several properties that make them well

suited to these applications. Both are readily

tailored by chemical substitution to grossly and

fi nely tune their electronic properties, includ-

ing fi lled and vacant state energies as well as

their absorption and excited state energies.

They can have conductivities ranging from as

low as those of the best wide gap insulators,

through semiconducting to metallic. Their

optical absorptivity can be significantly

larger than direct bandgap semiconductors,

with extinction coeffi cients as high as 10

6

cm

−1

. They can also be designed to emit with

high effi ciency, ranging in color from the UV

to the near-infrared. Lastly, both molecular

and polymeric materials can be peripherally

substituted to affect the mechanical and mor-

phological properties without signifi cantly

affecting the electronic properties of the

materials. This last property of organic mate-

rials is key to their future applications, as we

move toward organic materials by design, in

which the microscopic and macroscopic properties of the

compounds are tailored independently to achieve the optimal

materials for each application.

The fi rst organic optoelectronic device to go into full-scale

production was the organic light-emitting diode (OLED), and

signifi cantly more manufacturing capacity is being planned and

added at this time. Electroluminescence in organic materials has

been known since the mid-1960s.

25

,

26

However, the demonstra-

tion of the fi rst heterostructured OLEDs in the late 1980s set

the stage for major advances in effi ciencies and color tunability

of these devices.

27

,

28

By carefully controlling charge injec-

tion and recombination as well as the site of light emission in

OLEDs, internal effi ciencies have improved from ca. 5% in

1987 to 100% in the early part of this century.

29

–

32

The rapid

development of OLEDs, from a laboratory demonstration

to a commercial product, involved the dedicated work of a

broad range of scientists and engineers working together to both

Figure 4. Better samples lead to better understanding. (a) The left panel displays the

existence of growth of windows (shaded regions) in the hybrid molecular beam epitaxy

(MBE) growth stoichiometric SrTiO

3

as monitored from the cubic unit cell parameter

a .

23

The horizontal axis displays the beam equivalent pressure (BEP) ratio of titanium

tetraisopropoxide (TTIP) to strontium. The right panel displays the record mobilities that

become achievable from the lms grown in these growth windows.

24

Figure courtesy of

Susanne Stemmer. (b) Improved crystallinity in semiconducting polymer lms results in

signi cantly increased mobilities, as measured using a eld-effect transistor geometry.

Figure courtesy of Michael Chabinyc. R, generic organic group; S, sulfur; N, nitrogen;

n , an integer; F8T2, dioctyl uorene-bithiophene; P3HT, poly(3-hexylthiophene);

PBTTT, poly(2,5-bis(3-alkylthiophen-2-yl)thieno[3,2- b ]thiophene).

ADVANCES IN FUNCTIONAL MATERIALS: TOWARD THE PARADIGM OF MATERIALS BY DESIGN

687

MRS BULLETIN

•

VOLUME 37

•

JULY 2012

•

www.mrs.org/bulletin

understand and improve electroluminescent devices. The solu-

tions that were developed involved the use of thin amorphous

fi lms. Materials need to be amorphous to achieve acceptable fi lm

uniformity for the 10 nm to 40 nm fi lms that are used in OLEDs.

These fi lm thicknesses are necessary to keep the resistivity of the

device low enough to achieve low drive voltages. Manufactur-

ing these devices would be easier, and the power effi ciencies of

the devices would be improved if we could increase fi lm thick-

ness and decrease fi lm resistivity, respectively. While these two

goals seem mutually exclusive, if crystalline thin fi lms—some of

which are shown in Figure 4b —could be used for OLED prepa-

ration, it could be possible to both increase fi lm thickness and

decrease resistivity. Beyond simply growing uniform crystalline

fi lms, it is important to be able to predetermine the orientation

of the lattice to maintain maximum conductivity in the desired

direction, parallel or perpendicular to the substrate. Two other

existing devices could benefi t from such a level of materials

design and control: photovoltaics and transistors.

Organic solar cells have the potential to achieve high effi -

ciency for conversion of sunlight into electricity at a cost

well below existing solar technologies. Organic photovoltaics

(OPVs) with effi ciencies exceeding 10% have been certifi ed

by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory,

33

although

the structures have not been published. Effi ciencies of >25%

are possible for single junction cells.

34

While the OPV is in

many ways the microscopic inverse of the OLED, there are

important differences between the two. The high resistivity of

organic materials can be tolerated in an OLED, because very

thin fi lms could be used to minimize the bias needed to inject

and transport charge in the devices. If such thin fi lms are used

in OPVs, the problem of resistivity is minimized, but the fi lms

are so thin that very little light is absorbed. Thus, in an OLED,

it is possible to restrict all light emission to a very thin fi lm,

typically less than 30 nm, while in an OPV, the light absorption

must be spread over a much larger volume to achieve good

light collection. The most effi cient OPVs are those that use

thermal or solvent annealing to achieve a degree of crystallin-

ity in the organic materials. This is often done with donor (D)

and acceptor (A) materials in an interpenetrating network to

effi ciently collect excitons (i.e., the bulk heterojunction, BHJ),

since simple layered devices give exciton diffusion lengths that

are too short to give effi cient collection at the D/A interface.

This is again a technology that would be well served by being

able to control fi lm crystallinity and morphology over a large

area. Crystalline materials will have lower resistivity and higher

exciton diffusion lengths than the amorphous or polycrystalline

materials that are used currently. If it were possible to grow

highly crystalline thin fi lms of organic materials, with the pre-

ferred orientation of the organic moieties to direct excitons to

the D/A interface and charges out the electrodes, OPVs could

be fabricated with simple layered structures, rather than BHJs,

and achieve effi ciencies closer to the 25% theoretical limit.

35

Organic fi eld-effect transistors, OFETs, have advanced tre-

mendously over the last decade.

36

,

37

A key limitation of OFETs is

the carrier mobilities of organic materials. While values higher

than 1 cm

2

V

−1

s

−1

have been reported for organic materials, these

are still many orders of magnitude below those seen for inor-

ganic semiconductors, including GaAs and SrTiO

3

mentioned

earlier. The highest mobilities, and thus the best transistor per-

formance, are observed for single-crystalline materials. An

approach to using such materials in OFETs involves thermal

annealing to achieve crystalline grains that are larger than the

channel length.

The key to improving the effi ciencies of organic electronic

and optoelectronic devices is to develop the methodology to

grow organic materials in predetermined structures and orienta-

tion in large area thin fi lms. To develop this capability, it will

take a multidisciplinary and consistent effort. This will start

with theorists. It is possible to calculate many molecular param-

eters and even the bulk properties of a material in a given struc-

ture, to a limited degree. It has not been possible, however, to

reliably predict the morphology an organic material will adopt

in the solid state. In order to create methodologies for crystal-

line organic fi lm growth, it is important to couple researchers in

theoretical modeling with experimentalists to develop models

that effectively deal with both kinetic and thermodynamic

parameters to predict the structures of organic thin fi lms.

The fi rst step is to develop deposition tools that allow the

researcher to accurately control the deposition and growth

parameters for the organic thin fi lm, from both solution and

vapor sources. Next, theorists and experimentalists need to

work together to design, synthesize, and study the deposition

of molecules that are predicted to give preferred structures

under a set of deposition conditions. Materials that fail to

give the expected structure can be used to refi ne the model

and develop the deposition techniques further, so there are

no real failures in this approach. Working through this cycle

many times should provide a set of design parameters that

can be used to control the morphologies and properties of

organic thin fi lms.

New directions in nanoscience

The fi eld of nanomaterials has progressed considerably

since its emergence as a distinct discipline from cluster

and colloid science some 30 years ago. Advances have

been spurred by new chemistry knowledge as well as

new physical techniques and/or greater access to appro-

priate physical techniques (e.g., electron microscopy,

atomic force microscopy). At the present stage of devel-

opment, syntheses exist for a range of nanomaterials, mostly

single-element phases or binaries. This is in contrast to the

better-developed solid-state chemistry discipline, where

highly complex materials—ternary, quaternary materials

and beyond, and defect or dopant controlled materials—are

at the forefront of science. With the excellent foundation of

the past three decades of research, the fi eld of nanomaterials

is now poised to tackle a range of technical challenges. This

includes the synthesis of new, more complex materials, better

methods for nanoparticle integration, more detailed physical

characterization of existing materials (wherein new phenomena

ADVANCES IN FUNCTIONAL MATERIALS: TOWARD THE PARADIGM OF MATERIALS BY DESIGN

688

MRS BULLETIN

•

VOLUME 37

•

JULY 2012

•

www.mrs.org/bulletin

can be found), combined theoretical/experimental approaches

to understand nanoscale phenomena, and the deployment of

nanomaterials in device architectures.

The rich phase diagrams established for solid-state materials

provide a great source of new material compositions to be

targeted on the nanoscale, both as homogeneous (alloys or com-

pounds) and heterogeneous (e.g., core-shell) architectures. The

formation of homogeneous structures of ternary phases has been

achieved by direct synthesis from multicomponent solutions or

from chemical transformations.

38

Likewise, the ability to tune

the electro-optical properties of quantum dots by overcoating

with a semiconductor of a different bandgap, or the creation

of multifunctional structures by combining mutually exclusive

properties (e.g ., magnetism and photoluminescence) into a single

nanostructure

39

,

40

have proven to be powerful paradigms in nano-

material design. Structure-property-size correlations in complex

nanomaterials will be a fruitful area of exploration for some time

to come, driven by improved synthetic methods that enable high

quality nanocrystals and nanocomposites to be generated.

Doping or the introduction of defects into bulk solids is an

established method for tuning the optoelectronic properties,

but doping on the nanoscale has proven to be a complex prob-

lem, restricting the kinds of phenomena that can be accessed in

such materials. This problem has been addressed by a com-

bination of experimental and theoretical approaches,

41

which

revealed the key issue to be low binding energies for dopant

ions on certain crystalline faces. If the residence time is not

suffi cient for host layer overgrowth (i.e ., incorporation), low

to zero incorporation occurs. A key advantage of this “trapped

dopant” model is that binding energies for ions and competing

surfactants can be calculated for distinct facets, enabling doping

to be enhanced by appropriate solvent choices and/or crystallite

morphologies. Exploitation of this insight enables the effect

of coupling of size and doping on the nanoscale to be probed, for

example, the effects of quantum confi nement effects on magnetic

semiconductors. Combining theory with experiment is also shed-

ding light on physical phenomena, as demonstrated by the appli-

cation of d -band theory to the prediction of catalyst performance

42

or the modeling of interface scattering to predict optimal grain

sizes in thermoelectric nanocomposites.

43

The synergy that arises

when experiment and theory act in a feedback loop enables the

rational construction of nanomaterials for targeted applications.

Employing nanoparticles as discrete components for med-

ical applications based on optical and magnetic properties

was an early focus of investigation and continues apace.

The integration of nanomaterials into electronic devices,

of particular relevance for energy applications (photovolta-

ics, thermoelectrics, and batteries), has progressed more

slowly, as it is predicated on conductive particle interfaces.

Methods that generate well-formed discrete nanoparticles

typically produce materials with long-chain organics on the

surface, preventing facile transport of electrons. Advances

have been made by the use of conducting ligands,

44

ligands

that are thermally labile ( t -butylthiol),

45

replacement of organic

ligands with inorganic ligands such as molecular chalcogenide

clusters,

46

sulfi de,

47

or hydrazine,

48

and use of ligand removal

coupled to direct inter-particle bonding (sol-gel particle assem-

bly).

49

A consequence of such modifi cations is changes in sur-

face defects that modify luminescence characteristics and the

potential reduction in quantum confi nement in semiconduc-

tors. Alternative approaches focus on building nanostructures

directly from molecular building blocks, generating gels or

templated solids and obviating the need for ligand modifi cation

strategies altogether.

50

The role of serendipity: New inorganic pigments

from the search for multiferroics

In Horace Walpole’s 1754 retelling of a Persian fairy tale, three

well-raised princes from Serendip—modern-day Sri Lanka—

are continually making discoveries of things they are not in

quest of. The word that has emerged into common currency

from this tale, serendipity, is used to suggest the act of fi nding

something useful without really looking for it, or even perhaps

without prior knowledge of its existence. Modern materials sci-

ence is a chronicle of serendipitous discovery exemplifi ed by the

original discovery of superconductivity by Kamerlingh-Onnes,

the discovery in 1938 of polytetrafl uoroethylene (Tefl on) by Roy

Plunkett of DuPont Company, or the recent discovery of super-

conductivity in layered transition metal pnictides by the Hosono

group at the Tokyo Institute of Technology, who were in fact

searching for new transparent conductors.

51

In this regard, we

emphasize the importance of exploratory synthesis in materials

research, whose purpose is to escape the intellectual confi nes of

what we know in order to discover the new and the unexpected.

The recent discovery of highly durable and non-toxic inor-

ganic color pigments in oxides with transition metal cations in

trigonal bipyramidal (TBP) coordination can be considered as a

textbook example of how a systematic approach to discover new

functional materials in one area can lead to a totally unexpected

discovery in another, unrelated area. Both YInO

3

and YMnO

3

are known in the common orthorhombic and centrosymmetric

perovskite structure, but they are also readily prepared in an

acentric hexagonal structure ( Figure 5 , left panel),

52

,

53

consisting

of layers of Y

3+

ions separating layers of corner-shared M O

5

trigonal bipyramids ( M = In or Mn). This structure has been

of considerable recent interest because it exhibits an unusual

form of improper ferroelectricity (meaning the ferroelectric

polarization is not the primary driving force for the structural

change) as a consequence of the tilting of MO

5

polyhedra.

54

,

55

Such ferroelectricity is compatible with M -site magnetism and

therefore allows multiferroic behavior. To explore such multi-

ferroic behavior, the complete YIn

1− x

Mn

x

O

3

solid solution was

prepared. Despite the large size mismatch between In

3+

and

Mn

3+

, these cations are randomly disordered in the TBP sites.

56

Unfortunately, such a disorder suppresses the multiferroic order

parameter, rendering the system unsuitable for applications as a

magnetoelectric material.

57

However, a surprisingly intense and

bright blue pigment is obtained when Mn

3+

is introduced into the

trigonal bipyramidal sites in hexagonal YInO

3

, and over much of

the YIn

1− x

Mn

x

O

3

solid solution range, in spite of the fact that YInO

3

ADVANCES IN FUNCTIONAL MATERIALS: TOWARD THE PARADIGM OF MATERIALS BY DESIGN

689

MRS BULLETIN

•

VOLUME 37

•

JULY 2012

•

www.mrs.org/bulletin

and YMnO

3

are white and black, respectively. An intense blue

color is also obtained when Mn

3+

is introduced into trigonal bipy-

ramidal sites in other oxides. These unexpected discoveries have

led to the rational design of other earth-abundant, environmentally

benign and highly durable inorganic pigments. Substitution of Fe

3+

in hexagonal YInO

3

resulted in the formation of intense orange

compounds,

58

whereas the simultaneous substitution of Cu

2+

and

Ti

4+

along with Al

3+

in TBP sites resulted in the formation of oxides

exhibiting intense green color.

59

Serendipitous discoveries require intellectual effort and are not

simply a question of luck, and, indeed, we hark back to the tale

that tells us that the princes were actually well trained to observe

and interpret whatever they happened upon. Unpredictable results

and discoveries are as much a part of scientifi c endeavor, but ser-

endipity manifests when the alert and trained mind responds to

an unexpected situation. Basic exploratory research necessarily

incorporates serendipity, and thus sustained support for exploratory

research should not be neglected.

Conclusions

The systematic search for new functional materials specifi cally

designed to address existing challenges of technology has seen

a recent and well-deserved surge of attention. In particular,

the need to fi ll the materials discovery gap engendered by the

shrinking of once-prolifi c industrial laboratories

1

and the need

(and the necessary means) for approaches that can speed up

the arc from discovery to technology

3

have been emphasized.

In this article, we have simultaneously pointed to the needs

in some emerging areas as well as the requirements for better

Figure 5. (a) Crystal structure of polar, hexagonal YMnO

3

displaying the B cation (Mn

atoms here) in a trigonal bipyramidal environment, indicated by the blue polyhedra. Orange

spheres represent O atoms, and the dark gray spheres represent Y atoms. (b) Examples of

oxide pigments prepared by appropriate substitution of transition metal ions into trigonal

bipyramidal coordination.

materials that can enable new science. The

consensus that is emerging is that in areas

where a targeted search for better materials

is necessary, there is a need for strong col-

laboration between theory and experiment at

every level. At the same time, history tells

us that exploratory research and the abil-

ity to be surprised should continue to play

an important role and should be supported

appropriately.

Acknowledgment

We are very grateful to the National Science

Foundation (DMR 1115294) for support-

ing the Materials by Design Workshop, and

especially to Drs. Linda Sapochak and Daniele

Finotello for their support and encouragement.

We thank all the participants of the Workshop

for their many useful and creative inputs,

and acknowledge Michael Chabinyc, Craig

Fennie, John Mitchell, Joel Moore, Susanne

Stemmer, and Pat Woodward for providing

us with fi gures and explanations.

References

1 . Frontiers in Crystalline Matter: From Discovery to

Technology, Committee for an Assessment of and Outlook

for New Materials Synthesis and Crystal Growth ( National Research Council ,

2009 ).

2 . Materials Genome Initiative for Global Competitiveness ( White House Offi ce

of Science and Technology Policy , 2011 ) p. 6 .

3. G.R. Fleming , M.A. Ratner , Phys. Today 61 ( 7 ), 28 ( 2008 ).

4. J. Gertner , “ Innovation and the Bell Labs Miracle ,” New York Times (February

25, 2012 ).

5. W.C. Johnson , J.B. Parsons , M.C. Crew , J. Phys. Chem. 36 , 2651 ( 1932 ).

6. R. Juza , H. Hahn , Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 239 , 282 ( 1938 ).

7. E.F. Schubert , Light Emitting Diodes, 2nd ed. ( Cambridge University Press ,

UK , 2006 ).

8. S. Nakamura , T. Mukai , M. Senoh , Appl. Phys. Lett. 64 , 1687 ( 1994 ).

9. S. Nakamura , M. Senoh , S. Nagahama , N. Iwasa , T. Yamada , T. Matsushita ,

H. Kiyoku , Y. Sugimoto , Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 35 , 74 ( 1996 ).

10. N.A. Spaldin , M. Fiebib , Science 309 , 391 ( 2005 ).

11. T. Kimura , Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 37 , 387 ( 2007 ).

12. C.J. Fennie , K.M. Rabe , Phys. Rev. Lett. 97 , 267602 ( 2006 ).

13. J.H. Lee L. Fang , E. Vlahos , X. Ke , Y.W. Jung , L. Fitting Kourkoutis , J.W. Kim ,

P. Ryan , T. Heeg , M. Roeckerath , V. Goian , M. Bernhagen , R. Uecker , C. Hammel ,

K.M. Rabe , S. Kamba , J. Schubert , J.W. Freeland , D.A. Muller , C.J. Fennie , P. Schiffer ,

V. Gopalan , E. Johnston-Halperin , D.G. Schlom , Nature 466 , 954 ( 2010 ).

14. J.E. Moore , Nature 464 , 194 ( 2010 ).

15. M.Z. Hassan , C.L. Kane , Rev. Mod. Phys. 82 , 3045 ( 2010 ).

16. S. Chadov , X. Qi , J. Kübler , G.H. Fecher , C. Felser , S.C. Zhang , Nat. Mater.

9 , 541 ( 2010 ).

17. H. Lin , L.A. Wray , Y. Xia , S. Xu , S. Jia , R.J. Cava , A. Bansil , M.Z. Hassan ,

Nat. Mater. 9 , 546 ( 2010 ).

18. D.C. Tsui , H.L. Stormer , A.C. Gossard , Phys. Rev. Lett. 48 , 1559

( 1982 ).

19. H.L. Stormer , A. Chang , D.C. Tsui , J.C.M. Hwang , A.C. Gossard , W. Wiegmann ,

Phys. Rev. Lett.

50 , 1953 ( 1983 ).

20. W. Pan , H.L. Stormer , D.C. Tsui , L.N. Pfeiffer , K.W. Baldwin , K.W. West , Phys.

Rev. Lett. 90 , 16801 ( 2003 ).

21. J.K. Jain , Phys. Rev. Lett. 63 , 199 ( 1989 ).

22. H.Y. Hwang , Y. Iwasa , M. Kawasaki , B. Keimer , N. Nagaosa , Y. Tokura , Nat.

Mater. 11 , 103 ( 2012 ).

23. B. Jalan , P. Moetakef , S. Stemmer , Appl. Phys. Lett. 95 , 032906 ( 2009 ).

24. J. Son , P. Moetakef , B. Jalan , O. Bierwagen , N.J. Wright , R. Engel-Herbert ,

S. Stemmer , Nat. Mater. 9 , 482 ( 2010 ).

25. M. Pope , H.P. Kallmann , P. Magnante , J. Chem. Phys. 38 , 2042 ( 1963 ).

ADVANCES IN FUNCTIONAL MATERIALS: TOWARD THE PARADIGM OF MATERIALS BY DESIGN

690

MRS BULLETIN

•

VOLUME 37

•

JULY 2012

•

www.mrs.org/bulletin

26. W. Helfrich , W.G. Schneidere , Phys. Rev. Lett. 14 , 229 ( 1965 ).

27. W. Helfrich , W.G. Schneidere , J. Chem. Phys. 14 , 2902 ( 1965 ).

28. C.W. Tang , S.A. VanSlyke , Appl. Phys. Lett. 51 , 913 ( 1987 ).

29. C.W. Tang , S.A. VanSlyke , J. Appl. Phys. 65 , 3610 ( 1989 ).

30. H. Yersin , Ed., Highly Effi cient OLEDs with Phosphorescent Materials ( Wiley-

VCH , Berlin , 2007 ).

31. M.E. Thompson , P.E. Djurovich , S. Barlow , S.R. Marder , in Comprehensive

Organometallic Chemistry III , R.H. Crabtree , D.M.P. Mingos , Eds. ( Elsevier ,

Oxford, UK , 2007 ), Chapter 12.04.

32. L. Flamigni , A. Barbieri , C. Sabatini , B. Ventura , F. Barigelletti , Top. Curr.

Chem. 281 , 143 ( 2007 ).

33. http :// www . nrel . gov / ncpv / images / effi ciency_chart . jpg

34. C. Ulbricht , B. Beyer , C. Freibe , A. Winter , U.S. Schubert , Adv. Mater. 21 ,

4418 ( 2009 ).

35. N.C. Giebink , G.P. Wiederrecht , M.R. Wasielewski , S.R. Forrest , Phys. Rev. B

83 , 195326 ( 2011 ).

36. M. Małachowski , J. Ľmija , Opto-Electron. Rev. 18 , 121 ( 2010 ).

37. W. Wu , Y. Liu , D. Zhu , Chem. Soc. Rev. 39 , 1489 ( 2010 ).

38. Y. Vasquez , A.E. Henkes , J.C. Bauer , R.E. Schaak , J. Solid State Chem. 181

1509 ( 2008 ).

39. H. Kim , M. Achermann , L.P. Balet , J.A. Hollingsworth , V.I. Klimov , J. Am. Chem.

Soc. 127 , 544 ( 2005 ).

40. F.X. Redl , K.-S. Cho , C.B. Murray , S. O’Brien , Nature 423 , 968 ( 2003 ).

41. S.C. Erwin , L. Zu , M.I. Haftel , A.L. Efros , T.A. Kennedy , D.J. Norris , Nature

436 , 91 ( 2005 ).

42. E. Nikolla , J. Schwank , S. Linic , J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131 , 2747 ( 2009 ).

43. A. Popescu , A. Datta , G.S. Nolas , L.M. Woods , J. Appl. Phys. 109 , 103709 ( 2011 ).

44. D.J. Milliron , A.P. Alivisatos , C. Pitois , C. Edder , J.M.J. Fréchet , Adv. Mater.

15 , 58 ( 2003 ).

45. D.H. Webber , R.L. Brutchey , J. Am. Chem. Soc.

134 , 1085 ( 2012 ).

46. M.V. Kovalenko , M. Scheele , D.V. Talapin , Science 324 , 1417 ( 2009 ).

47. H. Zhang , B. Hu , L. Sun , R. Hovden , F.W. Wise , D.A. Muller , R.D. Robinson ,

Nano Lett. 11 , 5356 ( 2011 ).

48. J.J. Urban , D.V. Talapin , E.V. Shevchenko , C.B. Murray , J. Am. Chem. Soc.

128 , 3248 ( 2006 ).

49. J.L. Mohanan , I.U. Arachchige , S.L. Brock , Science 307 , 397 ( 2005 ).

50. D.R. Rolison , L.F. Nazar , MRS Bull. 36 , 486 ( 2011 ).

51. Y. Kamihara , H. Hiramatsu , M. Hirano , R. Kawamura , H. Yanagi , T. Kamiya ,

H. Hosono , J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128 , 10012 ( 2006 ).

52. A. Waintal , J. Chenavas , C.R. Acad. Sci. Paris 264 ( 1967 ).

53. C.W.F.T. Pistorius , J.G. Kruger , J. Inorg. Nucl. Chem. 38 , 1471 ( 1976 ).

54. B.B. Van Aken , A. Meetsma , T.M. Palstra , Acta Crystallogr. C 57 , 230 ( 2001 ).

55. B.B. Van Aken , T.M. Palstra , A. Filippetti , N.A. Spaldin , Nat. Mater. 3 , 164 ( 2004 ).

56. A.E. Smith , H. Mizoguchi , K. Delaney , N.A. Spaldin , A.W. Sleight ,

M.A. Subramanian , J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131 , 17084 ( 2009 ).

57. A. Dixit , A.E. Smith , M.A. Subramanian , G. Lawes , Solid State Commun.

150 , 746 ( 2010 ).

58. P. Jiang , J. Li , A.W. Sleight , M.A. Subramanian , Inorg. Chem. 50 , 5858 ( 2011 ).

59. A.E. Smith , A.W. Sleight , M.A. Subramanian , Mater. Res. Bull. 46 , 1 ( 2011 ).

Ram Seshadri is a professor in the Materials

Department and in the Department of Chemistry

and Biochemistry at the University of California,

Santa Barbara (UCSB). He received his BS degree

in chemistry from St. Stephens College, Delhi, in

1989, and his PhD degree in solid-state chemistry

from the Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore, in

1995. After some years as a postdoctoral fellow in

Caen, France, and Mainz, Germany, he started a

faculty career as an assistant professor in

Bangalore in 1999, before moving to UCSB in

2002. Seshadri’s research program addresses

structure-composition-property relations in

functional inorganic materials, focusing currently

on magnetic and correlated materials, catalysts, and phosphors. Seshadri can be

reached at the Materials Department and the Department of Chemistry and

Biochemistry, Materials Research Laboratory, University of California, Santa Barbara,

CA, USA; tel. 805-893-6129; and email [email protected] .

Stephanie L. Brock is a professor in the

Department of Chemistry at Wayne State

University. She received her BS degree in

chemistry from the University of Washington in

1990 and her PhD degree in chemistry from the

University of California, Davis, in 1995. From

1995 to 1999, she was a postdoctoral associate

at the University of Connecticut working on

nanoscale manganese oxide materials. Brock’s

research focuses on the synthesis, properties, and

applications of metal pnictide and chalcogenide

nanomaterials; the development of sol-gel

nanoparticle assembly methods and their

application to non-traditional materials; and

establishment of novel hybrid organic/inorganic nanomaterials for optoelectronic

and drug-delivery applications. Brock can be reached at the Department of

Chemistry, Wayne State University, Detroit, MI, USA; tel. 313-577-3102; and

email [email protected] .

Arthur P. Ramirez joined the University of

California, Santa Cruz, as dean of the Baskin

School of Engineering in May 2009 from LGS,

a subsidiary of Alcatel-Lucent. He earned his

BS and PhD degrees in physics at Yale University.

Ramirez spent much of his career at AT&T

Bell Laboratories, where he served as the

director of the device physics research department

before becoming leader of composite materials

and device development for LGS. His research

interests include frustrated systems, multiferroic

magnetic materials, and organic semiconduc-

tors. Ramirez can be reached at the Baskin

School of Engineering, University of California,

Santa Cruz, CA, USA; tel. 831-459-2158; and email [email protected] .

M.A. Subramanian is the Milton Harris Professor

of Materials Science at Oregon State University.

He received his BS and MS degrees from the

University of Madras, and his PhD degree from

the Indian Institute of Technology, Madras, in

1981. Following postdoctoral research at Texas

A&M University (1982–1984), Subramanian

joined Central Research & Development at

DuPont, where he remained until his recent

appointment at Oregon State. His research

interests include designing new inorganic

solid-state functional materials for emerging

applications in electronics, solid-state energy

conversion, and other areas. Subramanian can be

reached at the Department of Chemistry, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR,

USA; tel. 541-737-8235; and email [email protected] .

Mark E. Thompson is a professor of chemistry

and materials science at the University of

Southern California (USC). He received his BS

degree in 1980 from the University of California,

Berkeley, and his PhD degree in 1985 from the

California Institute of Technology—both in

chemistry. After two years as a postdoctoral

fellow at Oxford University, he accepted a position

as an assistant professor in the Chemistry

Department at Princeton University. Thompson

joined USC in 1995. His research program

involves the study of new materials and devices

for electroluminescence, solar energy conversion,

chemical/biological sensing, and catalysis.

Thompson can be reached at the Department of Chemistry, University of

Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90089, USA; tel. 213-704-6402; and

email [email protected] .