Clinical Aspects of Liver Diseases

4

0

Tr

eat

m

e

n

tof

liv

e

r

d

i

seases

Pa

g

e:

1

From m

y

tholo

gy

to

p

rovable treatment

8

72

1

.1 In

g

lobal medicine

8

72

1

.2 In hepatolog

y

8

72

2

C

linical studies

8

73

2

.1 T

yp

es of clinical studies

8

73

2

.2 Problems of clinical studies

8

73

2

.3 Placebo

8

74

2

.4 D

i

ff

i

culty of evaluat

i

on

8

74

2

.5 Provabilit

y

of treatmen

t

8

74

3

Pr

i

nc

ipl

es o

fli

ver t

h

era

py

8

75

3.1 Bas

i

c cons

i

derat

i

ons

8

75

3.1.1 L

i

ver therap

y

8

75

3.1.2 Liver thera

p

eutic a

g

ents

8

75

3.1.3 Protective thera

py

of the live

r

8

75

3.2 Precond

i

t

i

ons

8

75

3.3 Formsof“l

i

ver therapy

”

8

76

3

.

4 Aim

so

f

t

r

eat

m

e

n

t

8

76

3.5 Cate

g

ories of “liver thera

p

eutics” 876

3.6 Act

i

ve substances

8

7

6

3.7 Dose adjustment of medicaments 87

7

3.8 Si

g

nificance of

q

ualit

y

of life

8

7

8

3.9 Assessment of survival rate

8

7

8

4

Nutr

i

t

i

ona

l

t

h

erapy o

fli

ver

di

sease

s

8

7

8

4.1 Artificial feedin

g

8

79

4.1.1 Enteral feedin

g

8

79

4.1.2 Parenteral feed

i

n

g

8

7

9

4.2 D

i

et

i

n malnutr

i

t

i

o

n

880

4.3 Special diet

s

8

8

0

5

Dru

g

t

h

era

py

o

fli

ver

di

seases

881

5.

1

V

irustatics

881

5.1.1 Interfero

n

8

82

5.1.2 Nucleoside analogues

8

83

5

.2

I

mmunosu

pp

ressants

88

4

5.2.1 Glucocort

i

co

i

ds

88

4

5.2.2 Azath

i

opr

i

n

e

8

84

5.2.3 Cyclosporine

A

8

85

5

.

2

.

4T

ac

r

o

lim

us

88

5

5.2.5 C

y

clo

p

hos

p

ham

i

de

88

5

5.2.6 Methotrexate

8

85

5

.3

I

mmunostimulant

s

8

85

5.3.1

S

eleniu

m

88

5

5.3.2 Z

i

nc

886

5.3.3 Thymos

in

8

86

5

.4

U

rsodeox

y

cholic aci

d

8

86

5

.5

L

actulose

887

8

7

1

Pa

g

e

:

5

.6

Br

anched

-

chain amino acids

888

5

.7

Amino acids o

f

the urea c

y

cle 89

0

5

.8

D-

p

enici

ll

amin

e

892

5.

9

Somatostati

n

892

5.10 Terlipressin 89

2

5

.

11 S-adenos

y

l-L-methionine 89

3

5

.12

H

aemar

g

inate

893

5.

1

3 P

h

ytot

h

erapeutics

894

5.13.1 Essent

i

al phosphol

i

p

i

d

s

89

4

5.13.2 Silymarin 89

6

5.13.3 Gl

y

c

y

rrhiza

g

labr

a

89

7

5.13.4 Colch

i

c

i

n

e

89

7

5.13.5 Beta

i

n

e

897

5.13.6 Cynara scolymu

s

898

5.13.7 Bu

pl

eurum

f

a

l

catu

m

898

5.13.8 P

hyll

ant

h

us amaru

s

898

5.13.9 Sch

i

zandra ch

i

nens

i

s 898

5.13.10

C

atechin 898

6

S

ur

gi

ca

l

t

h

era

py

o

fli

ver

di

seases

898

6

.

1

TIPS

899

6

.2 Shunt operatio

n

899

6.

3 Block surger

y

9

0

0

6.

4

Live

rr

esection

900

6

.4.1 Bas

i

c

p

r

i

nc

ip

le

s

900

6

.4.2 Class

i

f

i

cat

i

on and

i

nd

i

cat

i

ons

9

01

6

.4.3 Re

g

eneration

9

0

2

6.

5

L

iver in

j

urie

s

902

7

Li

ver trans

pl

antat

i

o

n

903

7.1 Ind

i

cat

i

ons

9

0

3

7.2

C

ontraindications

9

0

5

7.3 Preo

p

erative dia

g

nostics

905

7.4 Preparat

i

on of pat

i

ents

906

7.5 Surg

i

cal aspects

9

0

6

7.6 Posto

p

erative feature

s

9

0

8

7

.

7Af

te

r

ca

r

ea

n

d

r

e

h

ab

ili

tat

i

o

n

910

8

S

oc

i

ome

di

ca

l

aspect

s

911

8.1 Health awareness

9

11

8

.

2Pr

e

v

e

n

t

iv

e

m

ed

i

c

in

e

9

1

2

8

.

3R

e

h

ab

ili

tat

i

on

912

8.4 Capac

i

ty for wor

k

912

8.5 Self-help group

s

9

1

4

앫

R

e

f

erences

(

1

⫺

4

45

)

9

1

4

(

Fi

g

ures 40.1

⫺

4

0.11; ta

bl

es 40.1

⫺

40.19

)

4

0

Tr

eat

m

e

n

tof

liv

e

r

d

i

seases

1

From mythology to provabl

e

t

r

eat

m

e

n

t

1.1 In

g

lobal medicine

䉴

Reco

mm

e

n

dat

i

o

n

sa

n

dd

i

scuss

i

o

n

so

n

t

h

et

r

eat-

m

ent of d

i

seases and

i

n

j

ur

i

es are as old as med

i

c

i

ne

i

tself. Accord

i

ng to our knowledge of earl

i

er t

i

mes

,

m

edicine has its origins i

n

m

ythological therapy

.

Thi

s

a

lso a

pp

lies to the treatment of liver diseases. •

U

n

d

erstan

d

a

bly,

“

surgica

l

me

d

icine

”

,es

p

ec

i

all

y

trau-

m

atology, en

j

oyed the h

i

ghest sc

i

ent

i

f

i

c status

in

a

ntiquity, since the actual “cause” and medical

“effect” were most obvious in this field. • M

y

tho

-

l

o

gi

cal

i

deas and r

i

tuals were therefore of m

i

nor s

ig

-

ni

f

i

cance to the barber surgeon:

i

n general, pract

i

cal

experience, manual skill and (mostly self-developed

)

app

ro

p

riate instruments

p

roduced the desired result

.

By

contrast,

“conse

r

vative medicine”

was c

h

arac-

ter

i

zed by mythology, steeped

i

nr

i

tual as well as

(mantic) divination and, for many epochs, mostly left

in the hands of the “

p

riest doctor”. In s

p

ite of some

-

t

i

mes aston

i

sh

i

n

g

l

yg

ood d

i

a

g

nost

i

cca

p

ab

i

l

i

t

i

es and

p

rognost

i

c accuracy, med

i

c

i

ne on the whol

e

⫺

espe-

c

ially treatment of the individual patien

t

⫺

was sub-

j

ect to the

p

revailin

g

m

y

tholo

gy

of the res

p

ectiv

e

e

p

oc

h

.

(

s. ta

b

. 40.1

)

W

ith the

g

radual re

j

ection of “m

y

thos” and a

s

tronger tendency to “logos”, therapeut

i

c measures

of a mytholog

i

cal and r

i

tual nature were

i

ncreas

i

ngly

a

bandoned. At the same time

,

h

o

wever, the a

bsu

r

d

a

ideas o

f s

p

eculat

i

ve thera

py

reached an unima

g

inable

l

evelofod

i

ousness. Obscure m

i

xtures, fantast

i

c prep-

a

rat

i

ons as well as nauseat

i

ng and even cruel treat

-

m

ent met

h

o

d

s were more an

d

more

p

ro

p

a

g

ate

d

an

d

app

lied. An insi

g

ht into these abnormalities of s

p

ecu

-

l

at

i

ve med

i

c

i

ne

i

sg

i

ven b

y

K.F. Paullin

i

(

1699

)

in hi

s

book:

„Neu-verme

h

rte,

h

ei

l

same Drec

k

-A

p

ot

h

e

k

e

“

(“Rev

i

sed and Enlarged Curat

i

ve D

i

rty Pharmacy”)

.

Wi

th the com

i

n

g

of the A

g

e of Enl

ig

htenment

i

n the

mi

ddle of the 18

t

h

centur

y

, accom

p

anied b

y

ara

p

i

d

i

ncrease

i

n med

i

cal knowledge, the calls for con

-

fi

rmed results became more and more urgent. Th

i

s

led to the ad

v

e

n

tof

em

p

irical thera

py

, which required

y

y

s

ubtle observation, critical anal

y

sis, careful examin

-

a

t

i

on and, above all, a wr

i

tten record of case h

i

stor

i

es

.

I

nth

i

s connect

i

on, surg

i

cal emp

i

r

i

c

i

sm was mor

e

s

tron

g

l

y

based on mor

p

holo

g

ical facts and ob

j

ectiv

e

m

ethodolo

g

ical ex

p

erience than the thera

p

eutic

emp

i

r

i

c

i

sm of conservat

i

ve med

i

c

i

ne

.

8

7

2

䉴

P

reventive thera

p

eutic em

p

iricism was a

pp

lied fo

r

t

he first time around 1600, when it was discovered b

y

“

thera

py

com

p

ar

i

son” that those seamen of the Eas

t

Ind

i

a Company who drank lemon

j

u

i

ce as a supple

-

m

entar

y

bevera

g

e did not contract scurv

y.

T

his was

th

e

b

asis o

f(

pro

b

a

bly)

t

h

e

f

irst

“

stat

i

st

i

ca

l”

t

h

era

p

eu-

ti

c stu

dy,

which

J

.

L

IN

D carried out in 17

4

7inordert

o

con

f

irm t

h

et

h

eor

y

o

f

a

l

emon-

j

uice t

h

erap

y

in severa

l

groups o

f

peop

l

e

b

ya

d

ministering various su

b

stances,

i

ncluding a “placebo”

.

T

h

i

s theory was also conf

i

rmed

b

y

J. C

oo

k in 1776, usin

g

a similar stud

y

desi

g

n.

•

F

urther therapeut

i

cm

i

lestones of med

i

cal h

i

stor

y

i

nclude the comparat

i

ve stud

i

es w

i

th digitalis

(W.

W

itherin

g

,

1785

)

,

s

mallpox vaccine

(

E.

J

enner

, 1798)

rr

a

n

d

m

ercur

y

treatment of syphilis

(

J.

P

earson

,

1800

)

.•

S

uch

com

p

arative studies, which were based on individua

l

o

bservations, aimed at

p

rovin

g

the effectiveness of

t

reatments; th

i

s development ended the epoch o

f

e

mp

i

r

i

cal therapy.

(2

)

(

ta

b

. 40.1

)

1

.2 In he

p

atolo

gy

䉴

D

ur

i

ng a per

i

od of about 3,000 years, hepatology als

o

e

xper

i

enced thes

e

historical medical epochs of therapy

,

(

1

.) mythological, (

2

(

(

.

)

s

p

eculative,

(

3

.)

em

p

irical, and

(

4

.) p

rovable.

(

s. tab. 40.1

)

• In addition to cata

p

lasm

s

⫺

c

ons

i

st

i

ng of var

i

ous herbs, o

i

ls or products der

i

ve

d

from an

i

mals, mostly prepared and used accord

i

ng t

o

m

y

tholo

g

icall

y

related idea

s

⫺

c

u

pp

in

g

, scarification

,

e

nemas, blood-lettin

g

and sternutators, the followin

g

mater

i

als were also used: dr

i

ed wolf l

i

ver w

i

th honey,

donkey l

i

ver w

i

th parsley, raw ox l

i

ver d

i

pped

i

n honey

,

o

x blood, etc. Some hi

g

hl

y

com

p

lex and fantasti

c

m

y

tholo

g

ical diets were a

pp

lied as well. Thera

p

euti

c

measures were often based on certa

i

n mytholog

i

ca

l

numbers or r

i

tual-dependent po

i

nts

i

nt

i

me and per

-

formed before statues of

g

ods or in connection with ani-

mal sacrifice

.

(

see c

h

a

p

ter 1.

)

• From the mediaeval

“d

i

rty pharmacy” came numerous, d

i

sgust

i

ng therapeu-

t

ic recommendations for patients with liver disease, e.g

.

consum

p

tion of the excrement of certain animals, ea

r

w

ax, dirt scra

p

ed off shee

p

udders, earthworms,

p

ol

y

-

pods d

i

ssolved

i

nw

i

ne, or a certa

i

n number of l

i

v

e

sheep’s lice. (s. p. 446) • Empirical treatment increasingl

y

made use of substrates of

p

lant ori

g

in or extracts o

f

Hy

oscamus, Cheliodonium, dandelion or milk thistle,

e

tc. To my knowledge, comparative therapeutic investiga-

ti

on

s

such as those mentioned above were not performe

d

in he

p

atolo

gy

. Until modern times, treatment of live

r

d

i

seases rema

i

ned almost exclus

i

vel

y

em

pi

r

i

cal

⫺

a

n

d

t

hus sc

i

ent

i

f

i

cally unproven.

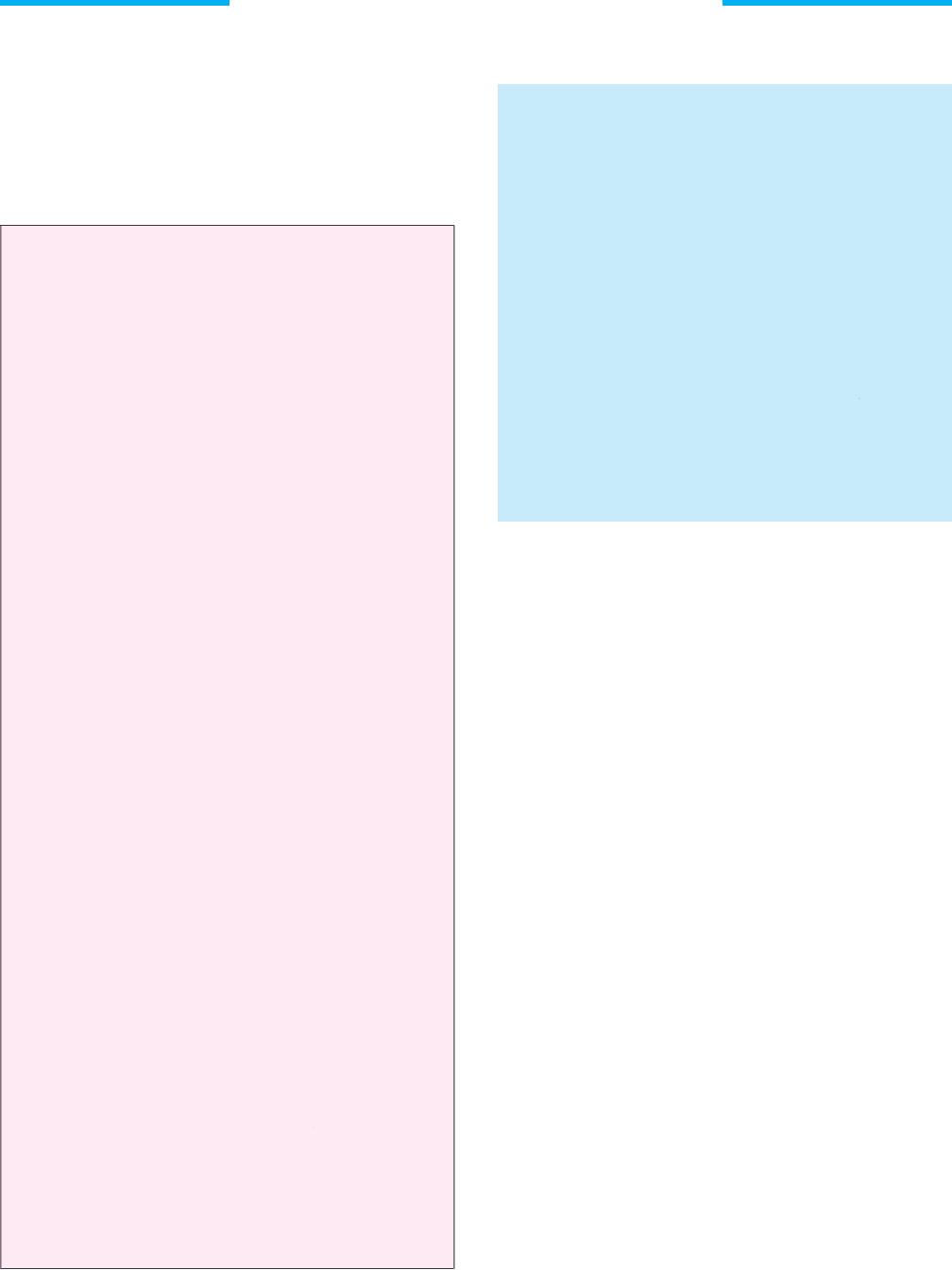

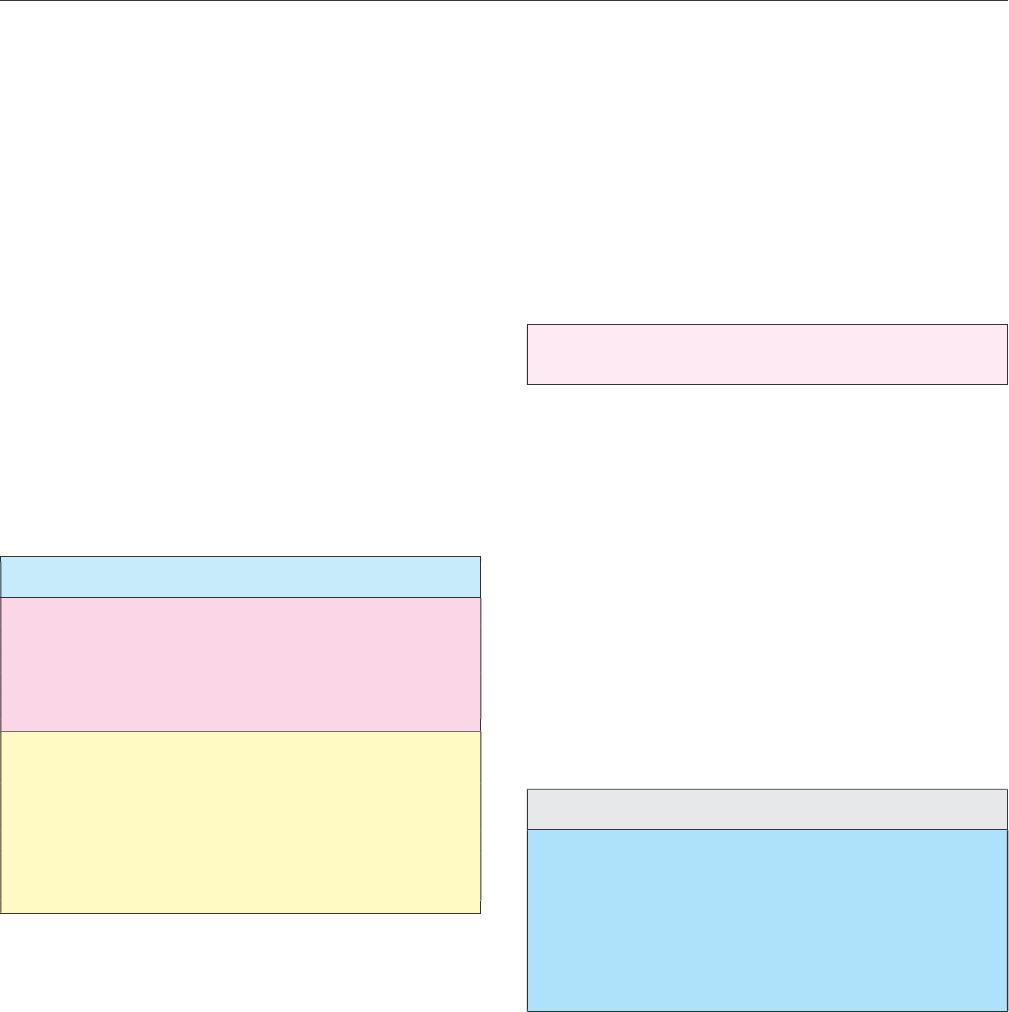

Treatment o

fl

iver

d

isease

s

M

y

tholo

g

ical therap

y

S

peculative therap

y

Emp

i

r

i

cal therap

y

La

c

k

o

f

T

hera

p

euti

c

p

roof

n

ihili

s

m

A

d

j

uvant therap

y

P

r

ov

a

b

l

e

tr

e

atm

e

n

t

•

p

h

armaco

l

og

i

ca

l

exper

i

menta

l

s

t

ud

i

es

•

clinicall

y

controlled studie

s

New approaches to treatment

g

enet

ic

bio

m

olecula

r

i

nvas

i

v

e

sur

g

ica

l

Tab. 40.1:

E

pochs of medicine:

(

1

.) mythological, (

2

(

(

.

) speculative

,

a

nd

(

3

.) emp

i

r

i

cal therapy, through to (

4

.) provable treatmen

t

The occas

i

onally pronounced “polypragmatism”

was

c

onfronted by the opposite extreme o

f

“

therapeuti

c

n

i

h

i

l

is

m

”

i

n the sense of treatment based on ex

p

ect-

a

t

i

on. Th

i

s

i

nev

i

tabl

y

led to frustrat

i

on on the

p

art o

f

t

he phys

i

c

i

an and to res

i

gnat

i

on on the part of the

patient suffering from a liver disease. • Thus, the real

-

i

zation of

p

rovable treatment also became an ur

g

en

t

c

hallen

g

e

i

nhe

p

atolo

gy.

2

Clinical studie

s

䉴 The f

i

rst eth

i

cal pr

i

nc

i

ples of b

i

omed

i

cal research ha

d

alread

y

been develo

p

ed in German

yp

rior to World

War I: relevant instructions were issued b

y

the Prussia

n

E

ducat

i

on Off

i

ce

i

n 1900. • At the proposal of the Ger

-

man Nat

i

onal Health Board, gu

i

del

i

nes for modern

curative treatment and for the

p

erformance of scientifi

c

studies in humans were issued in 1931 b

y

the Ministr

y

o

f Internal Affa

i

rs

i

n Germany.

Th

i

s measure was

i

ndeed the beg

i

nn

i

ng of scienti

f

ic

-

ally based therapy

.

• In 193

2

y

y

P

.M

artini

published hi

s

methodolo

gy

of thera

p

eutic research

(

8

)

,

and in 193

7

A.B. H

ill

established the

p

rinci

p

les of medical statis-

ti

cs

.

(6

)

2.1 Types of clinical studies

S

i

gn

i

f

i

cant contr

i

but

i

ons have s

i

nce been made concern

-

i

n

g

the im

p

ortance,

p

erformance and evaluation of

c

lin

-

ica

l

studies.

(

5, 7

)

In recent

y

ears, statistical and le

g

al

issues in

p

articular have been discussed

.

(

3, 10, 11, 12

)

•

C

ontrolled cl

i

n

i

cal stud

i

es are r

ig

htl

y

called for and the

y

8

73

are

i

nd

i

spensable for avo

i

d

i

ng therapeut

i

cm

i

s

j

udgement

deriving from “trial and error” and for creating a

n

ob

j

ective basis for official decisions. The

y

ma

y

be car

-

ri

ed out, as far as

p

oss

i

ble com

p

arat

i

vel

y

, as a retros

p

ec-

t

i

ve or prospect

i

ve

i

nvest

i

gat

i

on. • A retrospective study

is a backward-looking review of facts and effects, i.e.

a

g

ainst a time axis, to identif

yp

recedin

g

causes. The

data can be collected accord

i

n

g

toaf

i

xed

p

la

n

(

ⴝ

p

ro-

l

ective

)

o

r generated before the study beg

i

n

s

(

ⴝ

retro

l

ec

-

t

ive). Furthermore

,

a distinction is made between

f

ollowin

g

the individual course from the time the caus-

a

t

i

ve factor a

pp

ears throu

g

h to the onset of effec

t

(

ⴝ

c

ohort

)

a

nd follow

i

ng the

i

nd

i

v

i

dual course from the

onset of effect back to the earliest possible point in tim

e

when the causative factor a

pp

eare

d

(

ⴝ

t

rohoc

)

(

A.R.

F

e

in

s

tein

,

1977

)

. Thus, a retrospect

i

ve study

i

s deemed

s

cientifically correct if its execution is justified and the

m

ethodolo

gy

is clearl

y

defined. • A

p

ros

p

ect

i

ve stud

y

s

tarts from causat

i

ve factors, observ

i

n

g

the effect ove

r

the course of t

i

me.

(

7, 10, 12)

Sp

ecial case

s

a

r

e the

open

(

non-

bl

in

d)

stu

dy

o

n

the o

n

e

ha

n

da

n

d the

crossover stu

dy

o

n

t

h

eot

h

e

rh

a

n

d.

• Thi

s

means that the controlled cl

i

n

i

cal study

i

s “fundamen

-

tally” (

i

.e. w

i

th some except

i

ons) the sole and mos

t

e

ssential tool for obtainin

gp

roof of the efficac

y

of

a

g

iven substance. If the conditions for a controlled clin-

i

cal study cannot be met, then

i

t must be d

i

spensed w

i

th.

Th

e t

yp

o

l

o

gy

of cl

i

n

i

cal stud

i

es d

i

fferent

i

ates four t

yp

e

s

accord

i

ng to the

i

ra

i

ms:

(

1

.

) pharmacolog

i

cal stud

i

es

,

(

2

(

(

.

)

thera

p

eutic ex

p

lorative studies,

(

3

.)

thera

p

eutic con

-

firmative studies, and

(

4

.)

dru

g

-monitorin

g

studies. Th

e

p

urpose of the last-ment

i

oned group

i

stodef

i

ne the

cost/benef

i

trat

i

o more prec

i

sely,

i

dent

i

fy rare s

i

de

e

ffects and

p

rovide better dosa

g

e recommendations.

2

.

2Pr

ob

l

e

m

so

f

c

l

i

n

ica

l

studies

T

here is a vast arra

y

of literature dealin

g

with still con

-

trovers

i

al aspects of controlled cl

i

n

i

cal stud

i

es.

•

W

e

s

hould be aware that on the one hand

,

medicine is not an

e

xact science an

d

on t

h

eot

h

er

h

an

d

,

h

umans

d

o not re

p

re

-

s

ent a quanti

f

ia

bl

emo

d

e

l

wit

hd

ata on ca

ll

as nee

d

e

d

.

P

roblems

i

ncl

i

n

i

cal stud

i

es often ar

i

se

in

d

i

fferent f

i

elds:

1

. eth

i

ca

l

4

. psycholog

i

ca

l

2

. methodological 5. heuristic

3

.le

g

a

l

6. eco

n

o

m

ic

P

roof

i

n the str

i

ct sense cannot be del

i

vered by a con-

trolled cl

i

n

i

cal study, wh

i

ch has been called the “sacred

co

w”

.

(

5

)

However, the prob

a

bility of statistical error in

a

terms of the chosen tar

g

et criteria can be fixed i

n

advance. In clinical studies, different inter

p

retations o

f

r

esults are st

i

ll poss

i

ble, s

i

nce “

intuitive medical obse

r

va

-

tion and

j

udgement remain indispensable in the individual

Ch

a

p

ter 4

0

c

ase

”

(

E.

B

uc

hb

o

rn

,

1982

)

.

•Th

e

tria

d

of emp

i

r

i

c

i

sm,

i

ntu-

i

t

i

o

n

a

n

d

lo

g

i

c

is necessary in both diagnosis and treat

-

m

e

n

t

(

R.

G

ross, 1988

)

.

2

.

3

Placeb

o

A

placebo (Latin, “I shall please”) or ADT

(

⫽

a

n

ywha

t

yo

u

d

es

ir

e

t

hin

g)

is a “dumm

y

” without an

y

active sub

-

stance,

i

dent

i

cal

i

na

pp

earance to the res

p

ect

i

ve act

i

v

e

d

rug and not des

i

gned to be effect

i

ve. Th

i

s term has

bee

nkn

o

wn

s

in

ce t

h

e

14

th

c

entur

y

.

(

4)

•

In med

i

c

i

ne,

a

placebo assumes two ro

l

es

:

(

1

.) as a therapeut

i

c agent

in

t

he practical treatment of patients, intended to have a

n

“

effect” on a disease or a s

y

m

p

tom, or exertin

g

suc

h

effects without the physician’s knowledge, and (

2

(

(

.

)

as

a

control substance

i

ncl

i

n

i

cal stud

i

es w

i

th drugs. • I

n

i

ndividual cases

,

even objective

c

hanges in physiological

fu

n

ct

i

o

n

sa

n

d

s

p

ec

i

f

ic

eff

ects ma

yb

e

d

emonstra

bl

e. T

h

e

f

orm of adm

i

n

i

strat

i

on and the dosa

g

eofa

p

lacebo, the

phys

i

c

i

an’s personal

i

ty (and that of the pat

i

ent) and th

e

i

ntensity of the disease situation may lead to a weaken

-

i

n

g

or

p

otentiation of the

p

lacebo effect. The im

p

ortant

(i

nd

i

v

i

dual and soc

i

al

)

eth

i

cal

i

ssues assoc

i

ated w

i

th

placebo adm

i

n

i

strat

i

on concern both the pat

i

ent and th

e

physician, who have to be informed in general about

such

p

rocedures. These issues have been clarified b

y

law

a

fter be

i

n

g

d

i

scussed

i

n deta

i

l and assessed on the bas

is

o

f exper

i

mental f

i

nd

i

ngs

.

䉴

The

p

lacebo effect in controlled clinical studie

s

s

hould never be re

g

arded as “zero”, even thou

g

h this

i

s, of course, des

i

red

(

or even

i

m

p

uted

)

from th

e

s

tat

i

st

i

cal v

i

ewpo

i

nt.

Wi

th

i

n the sco

p

eofcl

i

n

i

cal stud

i

es, valuable econom

ic

i

nformat

i

on on med

i

cal procedures can (and should) b

e

obtained. Today

,

eco

n

o

mi

c assess

m

e

n

t

a

ssumes a special

role in clinical studies, and because of its com

p

lex strati-

fi

cat

i

on and the

g

eneral need for rat

i

onal

i

zat

i

on, e.

g

.

i

n

terms of the cost/benef

i

t analys

i

s,

i

t

i

sl

i

kely to become

m

ore and more important. The quality-adjusted lif

e

y

ea

r

(

G. W.

T

o

rr

a

n

ce

,

1987)

s

hould be

i

ncluded

i

nth

e

assessment. (s. p. 878

)

2

.4 Difficult

y

of evaluation

P

rov

i

ng the eff

i

cacy of a (surg

i

cal or med

i

c

i

nal) thera-

p

eut

i

c measur

e

⫺

and this also applies in hepatolog

y

⫺

i

sver

y

difficult, as it mainl

y

de

p

ends on

t

w

o facto

r

s:

1

. non-comparab

i

l

i

ty of

i

nd

i

v

i

dual humans

2. non-com

p

arabilit

y

of individual diseases

S

tatistical methods cannot render eithe

r

non

-

compar

-

a

b

i

l

i

t

y

of individual humans or that of diseases com

p

ar

-

able

⫺

a

t best, the

y

ma

y

com

p

ensate

i

tb

y

means o

f

l

arge pat

i

ent numbers or are able to assess samenes

s

8

7

4

under certa

i

nc

i

rcumstances.

(

1, 5

)

•S

tat

i

st

i

ca

l

compar

-

a

bility

o

f different patient groups can only be achieved

if

t

hree re

q

u

i

rements

a

r

e

m

et:

1. e

q

ual

i

t

y

of structure

2. equal

i

ty of observat

i

on

3. equality of representation

E

ven with

g

reat dia

g

nostic effort, no convincin

g

s

truc-

t

ura

l

equa

l

ity

i

s obtainable. Conse

q

uentl

y

, randomiza-

ti

on alone does not guarantee a valuable cl

i

n

i

cal study.

Desp

i

te these problems

,

t

hree study types

s

hould (and

must

)b

e use

d:

1

.

E

x

a

min

at

i

o

n

o

f

e

ff

ect

⫽

chan

g

einan

y

one

p

aramete

r

2.

E

xamination of efficacy

⫽

cureorim

p

rovement of diseas

e

3.

E

xamination of superiorit

y

⫽

im

p

rovement of

p

arameters, or cure, o

r

i

m

p

rovement of disease b

y

conventional

th

era

py

vs. new t

h

era

py

2.5 Provability of treatmen

t

I

ncl

i

n

i

cal stud

i

es

i

nvolv

i

ng drug

s

⫺

this also applies t

o

h

epato

l

og

y

⫺

t

he terms “effect” and “efficac

y

”havenot

alwa

y

s been a

pp

ro

p

riatel

y

distin

g

uished, but were often

(

erroneously) cons

i

dered

i

dent

i

cal. • Th

e

e

ffect of a spe

-

c

i

f

i

c drug (or “l

i

ver therapeut

i

c”) show

i

ng changes

i

n

an

y

measured

p

arameters or reactions is easier to

p

rove

t

han its efficac

y

in the sense of cure or im

p

rovement of

d

i

sease. Therapeut

i

c eff

i

cacy

(

or eff

i

cacy of “l

i

ver ther-

apy”)

i

s def

i

ned by the d

i

fference between the un

i

nflu

-

e

nced disease course

(

i.e.

p

ossible or usual course

)

and

t

he disease course chan

g

ed b

y

thera

p

eutic measures

(

i.e

.

actual course)

.

There is, however, no chance of ever

o

bserving and assessing the “possible” and the “actual”

d

isease course simu

l

taneous

ly

.

(

1

.

)Th

e

m

arketability of a pharmaceut

i

cal preparat

i

o

n

is controlled by an act of administration. In this context,

t

hr

ee c

r

ite

r

ia

m

ust be satisfied for the licensin

g

of medic-

aments,

i

nclud

i

n

g

“l

i

ver thera

p

eut

i

cs”

:

1.

qua

l

it

y

2

. sa

f

ety

3

.

e

fficac

y

(

2

(

(

.

)

T

h

eterm“

q

ual

i

t

y”

is defined b

y

various criteria:

p

urit

y,

i

dent

i

t

y

, content,

g

alen

i

c

p

ro

p

ert

i

es and tem

p

erature sta-

bi

l

i

ty of a substance. • The ter

m

“sa

f

ety

”

i

s def

i

ned

i

n

r

elation to acute and chronic toxicit

y

, foetal toxicit

y

and

fertilit

y

,muta

g

enic and carcino

g

enic

p

otential.

(

3

.

) As regards the term

“

efficacy”

,

no legal definition

e

xists. As a rule, efficac

y

is defined b

y

the sum of desired

Treatment o

fl

iver

d

isease

s

e

ffects w

i

th regard to a certa

i

n therapeut

i

ca

i

m. Thus

,

i

n terms of the licensing regulations, the efficacy of a

dru

g

, includin

g

“liver thera

p

eutics”, ma

y

be defined a

s

“

t

h

ea

b

stract qua

l

ity o

f

me

d

icine to ac

h

ieve t

h

erapeuti

c

success with proper use, accidental and placebo success

h

avin

g

been excluded

”

(

K.J.

H

ennin

g

,

1978

)

.

T

h

eUSFoo

d

,

D

rug and Cosmet

i

c Act def

i

nes the term “eff

i

cacy”

i

n

a

s

imilar manner. • Mere proof of quality and safety i

s

s

ufficient for medicine that does not have be licensed

,

but onl

y

re

gi

stered; no

p

roof of eff

i

cac

yi

sre

q

u

i

red. Th

is

a

ppl

i

es to homoeopath

i

c remed

i

es, for example.

(

4

.) The eff

i

cacy of med

i

c

i

nal remed

i

es,

i

nclud

i

ng “l

i

ve

r

therapeutics”, may be regarded as a

c

ontinuum, i

.e.

fr

om

“

ver

y

wea

k”

to

“h

ig

hly

potent

”

.

T

hus, efficac

y

is also

p

roven when the substance

i

s shown to be onl

y

sl

ig

htl

y

effect

i

ve or

i

s only effect

i

ve

i

n some pat

i

ents (

i

nd

i

v

i

dual

c

ases). Principally (

⫽

e

xceptions are possible), proof o

f

efficac

y

is to be

p

rovided b

y

controlled clinical studies

.

No

p

roof of su

p

er

i

or

i

t

y

of the dru

g

under

i

nvest

ig

at

i

o

n

over the standard preparat

i

on

i

s requ

i

redbylaw.No

r

d

oes the licensing procedure check whether there is

a

p

otential need for the dru

g

in

q

uestion

.

T

hus the aim of clinical studies is to provide proof o

f

sa

f

et

y

and a

pp

ro

p

riate e

ff

icac

y

. • However, it is essen-

ti

a

l

to ensure t

h

e

q

ua

li

t

y

o

f

t

h

eran

d

om

i

ze

d

, contro

ll

e

d

t

rials in every respect

!

(9

)

3

Principles of liver therap

y

3.1 Bas

i

c cons

i

derat

i

ons

First of all, two terms need rectif

y

in

g

, since th

e

su

p

erficial

y

et incorrect use of the desi

g

nation

s

“live

r

t

herapy” an

d

“

protective therapy of the liver

”

have

rendered

i

t fundamentally more d

i

ff

i

cult to make

accu

r

ate state

m

e

n

ts.

Th

ese te

rm

sa

r

e

r

e

li

cs

fr

o

m

t

h

e

e

p

ochs of s

p

eculative or em

p

irical thera

py

and con

-

s

t

i

tute the or

i

g

i

n of the catchword “therapeut

i

cn

i

h

i

l-

i

sm”. (s. tab. 40.1)

3.1.1 L

i

ver thera

py

T

here has never been and there st

i

ll

i

s not any “l

i

ve

r

thera

py

” in the true sense ⫺

a

nd no such thera

py

will

exist in future either. The liver as the lar

g

est biochemica

l

p

erformance centre of the bod

yi

s constantl

y

act

i

ve

in

s

ome 11 ma

j

or metabol

i

c areas w

i

th 60

⫺

7

0

i

ntegrated

p

artial functions. In order to accom

p

lish the man

y

tasks, about 300 billion liver cells undertake a

pp

rox. 50

0

b

i

omolecular react

i

ons da

i

l

y

⫺

i

ndeed an unbel

i

evable

f

eat. Consequently,

i

t

i

s not poss

i

ble for drugs to have

a

n

e

ff

ect o

n

t

h

e

liv

e

r

as a

wh

o

l

e.

However

,

rr

t

hera

p

ies fo

r

l

i

v

e

r

diseases

o

rt

h

erapies

f

or

h

epato

l

ogica

l

symptoms are

available.

W

i

th th

i

sl

i

ngu

i

st

i

c correctness, our therapeu-

8

75

t

i

c efforts

i

n hepatology become

r

ealistic

a

nd objectifi

-

able

.

There are far more than 100 liver diseases plus

v

ariants and diverse com

p

lications. A lar

g

e number of

t

hem can be treated successfull

y

w

i

th

p

harmacolo

gi

cal

r

eg

i

men

s

⫺

somet

i

mes w

i

th str

i

k

i

ngly good result

s

⫺

as

w

ell as, of course, by invasive and surgical therapy

.

3

.1.2 L

i

ver thera

p

eut

i

ca

g

ents

I

n the str

i

ct l

i

ngu

i

st

i

c and hepatolog

i

cal sense, there

is

n

o such thing as liver therapeutic agents. How

e

v

er,

t

hi

s

u

n

f

ortunate ter

m

i

sfre

q

uentl

y

⫺

and indeed deliberatel

y

⫺

used rhetor

i

call

yi

n

p

ubl

i

cat

i

ons or for adm

i

n

i

strat

i

v

e

r

easons. Here, the express

i

o

n

“hepatic agents”

(

analo-

gous to cardiac, otologic and diuretic agents, etc.) woul

d

b

e more correct and not so

p

romisin

g

in the

p

o

p

ular

sense as the des

ig

nat

i

on “l

i

ver thera

p

eut

i

ca

g

ents”. •

In

any case, one ought to be aware of the possible psycholog

-

ical e

ff

ect o

f

such a term, especiall

y

with regard to

a

“pl

ace

b

o

”

.

(

s.

p

. 874

)

3

.1.3 Protect

i

ve thera

py

of the l

i

ve

r

S

imilarly, there is no generally protective therapy of the

liver. Liver “

p

rotection” as such ma

y

include active

v

acc

i

nat

i

on a

g

a

i

nst v

i

ral he

p

at

i

t

i

s A or B, for exam

p

le

,

and,

i

naw

i

der sense, also pass

i

ve

i

mmun

i

zat

i

on after

e

xposure or general avoidance of typical liver noxae

.

This can “

p

rotect” the liver from diseases

.

(16

)

I

n

i

n-v

i

tro

a

n

d

i

n-v

i

vo ex

p

er

i

ments

,

certa

i

n substance

s

can be stud

i

ed for the

i

r protect

i

ve effect on the hepato-

c

y

tes or endothelial cells

(

includin

g

biomembranes an

d

or

g

anelles

)

under the influence of various noxae or

tox

i

ns. Many su

b

stances

h

ave

b

een s

h

own to

d

isp

l

ay

d

is

-

tinct protective properties experimentall

y

under various

i

nvesti

g

ative con

d

itions.

S

uch studies are not

,

h

o

w

e

v

er,

admissible in humans. • These ex

p

erimental

p

rotectiv

e

p

ropert

i

es may also be of therapeut

i

c value

i

n

i

nd

i

v

i

dual

cases (e.g. appl

i

cat

i

on o

f

s

ilibini

n

i

n Aman

i

ta po

i

son

i

ng)

.

A“l

i

ver-protect

i

ve preparat

i

on” must therefore be cap

-

able of

p

rotectin

g

the he

p

atoc

y

tes

(

as well as the sinu

s

e

ndothelium

)

from a

p

articular liver toxin, or from tw

o

to three clearly def

i

ned (or,

i

n the opt

i

mal case, all obl

i-

gate) l

i

ver tox

i

ns

,

b

y

administration be

f

ore or, at the lat

-

e

st, w

h

en t

h

e

d

ama

g

e occurs. Th

e use o

f

a substa

n

ce

i

n

e

xistin

g

cellular dama

g

e would be classified as “ther-

apy” and no longer “protect

i

on”. The term protect

i

ve

l

i

ver therapy clearly

i

mpl

i

es prophylax

is

⫺

w

h

i

ch, apar

t

from the above exce

p

tions

(

e.

g

. vaccination

)

, is usuall

y

n

ot feasible under the

p

rovisions of the res

p

ective health

i

nsurance system.

(16

)

3.2 Precond

i

t

i

ons

T

he

q

uestion of

p

rovabilit

y

of a certain thera

py

is als

o

de

p

endent on various

facto

r

s

in he

p

atolo

gy

:

(

1

.) k

now-

ledge of the spontaneous course of a l

i

ver d

i

sease (not

Ch

a

p

ter 4

0

known

i

n

i

nd

i

v

i

dual cases, but only globally assessable)

,

(

2

(

(

.

) endogenous factors (gender, age, genetics), and (

3

.)

exo

g

enous influence

(

e.

g

. lifest

y

le, noxae,

p

atient com

-

p

l

i

ance

)

. These

i

m

p

onderables can scarcel

y(i

f at all

)

be

i

ntegrat

i

vely assessed or excluded even us

i

ng subtle stat-

ist

i

ca

lm

et

h

ods.

R

a

n

do

miz

at

i

o

n

a

n

d doub

l

e

-

b

lin

dc

lin-

ica

l

t

ri

a

l

sca

n

do

n

o

m

o

r

et

h

a

n

ba

l

a

n

ce out t

h

ese d

iff

e

r

-

ences. In order to obta

i

n usable data, certa

in

s

tat

i

st

i

cal

c

ondition

s

s

hould be fulf

i

lled as far as poss

i

ble:

⫺

homogeneous f

i

nd

i

ngs

in

⫺

homo

g

eneous

p

atient

s

with

⫺

homogeneous d

i

seas

e

T

hese re

q

u

i

rements are d

i

ff

i

cult to meet even

i

n con

-

trolled cl

i

n

i

cal stud

i

es

i

n hepatology. Moreover, the us

e

o

fm

ed

i

cat

i

o

ninliv

e

r

d

i

sease

i

s based o

nf

u

r

t

h

e

r

esse

n-

t

i

a

l

c

l

i

n

ica

l

co

n

ditio

n

s:

1

. Deta

i

led hepat

i

cd

i

agnos

i

sw

i

th exact class

i

f

i

cat

i

on

o

f

t

h

e

liv

e

r

d

i

sease

2

.

I

de

n

t

ifi

cat

i

o

n

a

n

de

limin

at

i

o

n

o

f

t

h

e causat

iv

e

noxa

(

e

)

3

.El

i

m

i

nat

i

on of concom

i

tant negat

i

ve factors or

add

i

t

i

o

n

a

ln

o

x

ae

T

herapeut

i

c uncerta

i

nt

i

es or d

i

ffer

i

ng conclus

i

ons re-

g

ard

i

ng drug effects or eff

i

cacy may thus be attr

i

bute

d

to var

y

in

g

de

g

rees of methodolo

g

ical inaccurac

y

:

⫺

di

fferent d

i

sease courses

with

⫺

d

ifferent

p

atho

g

enesi

s

in

⫺

di

fferent pat

i

ent

s

and an

⫺

i

nsufficient detailed dia

g

nosi

s

were subm

i

tte

d

to

⫺

j

oint statistical evaluation

3

.3 Formsof“l

i

ver therapy”

C

ausal treatment of l

i

ver d

i

seases, wh

i

ch

i

s rarely (

i

f

ever

)

feasible, should achieve the com

p

lete eliminatio

n

of the actual cause

(

s

)(

e.

g

. elimination of the causativ

e

noxa, ant

i

v

i

ral treatment, gene therapy

i

n hered

i

tary

li

ver d

i

seases).

•

T

reatment of pathogenetic primary reac

-

t

i

o

n

s

(

e.

g

. with interferon, immunosu

pp

ressants or

p

eni

-

c

illamine

)

is aimed at interru

p

tin

g

the “

p

ostcausal

”

p

athogenes

i

s.

•

Treatment of d

i

sease progress

i

o

n

i

nter-

v

enes

i

n the patholog

i

cal process

i

n a last

i

ng and eff

i-

c

ient manner and thus

p

revents or slows down the

g

en

-

erall

y

dan

g

erous conse

q

uences

(

e.

g

. inhibition of

c

holestas

i

s, f

i

brogenes

i

s and portal hypertens

i

on).

•

8

76

A

lmost all substances used

i

n hepatology are classe

d

as

s

ymptomatic treatment

.

These substances help (

1

.) to

combat malaise and disturbances secondar

y

to the live

r

disease (e. g. antipruritics), and (

2

(

(

.

)

to

i

nfluence th

e

structures and funct

i

ons of the hepatocytes and endo

-

t

helial cells as well as the bile capillaries (e.g. antioxi

-

dants, essential

p

hos

p

holi

p

ids, UDCA, sil

y

marin

).

(16

)

3

.

4 Aim

so

f

t

r

eat

m

e

n

t

Drug therapy of a part

i

cular l

i

ver d

i

sease or compl

i

ca-

ti

ve development must have bas

ic

t

reatment aims

.

T

h

e

p

rimar

y

thera

p

eutic aim is to eliminate the existin

g

causative factors and

p

atho

g

enetic mechanisms. Th

e

f

i

nal goal

i

salwaysthe

rehabilitation

o

f the l

i

ver pat

i

ent.

(

s. tab. 40.2) (s. p. 912

)

1. Eliminatin

g

or definitivel

y

overcomin

g

the caus

e

of disease

(

as far as

p

ossible

)

as well as

p

romotin

g

and s

p

eed

i

n

g

u

pi

ts cur

e

2. Inhibition of inflammator

y

reactions

3. Curbin

g

of mesench

y

mal reactions

4

. Modulat

i

on of

i

mmunolog

i

cal react

i

on

s

5

. Support/normal

i

zat

i

on of l

i

ver cell funct

i

on

s

6. Stimulation of hepatic regeneration

Rehab

i

l

i

tat

i

o

n

Ta

b

.

4

0.

2

:

T

reatment a

i

ms

i

nl

i

ver d

i

sease

s

䉲

䉲

䉲

䉲

䉲

䉲

3.5

C

ategor

i

es of “l

i

ver therapeut

i

cs

”

A

number of substances and

p

re

p

arations are availabl

e

for the treatment of liver diseases. The

y

can be cate

g

or

-

i

zed

i

nvar

i

ous ways. (s. tab. 40.3

)

1

.

P

ro

p

h

y

lactics: e.

g

. immuno

g

lobulins or vaccines

a

g

ainst he

p

atotro

p

ic virus infections

2

.

Ant

i

dotes: e.g. s

i

l

i

b

i

n

i

naga

i

nst Aman

i

t

a

p

o

i

son

i

ng or N-acetylcyste

i

ne

i

n paracetamo

l

intoxication, haemar

g

inate in acute

p

or

p

h

y

ri

a

3

.

P

r

i

mar

y

l

i

ver thera

p

eut

i

cs

:

e

.

g

.

p

enicillamine,

glucocort

i

co

i

ds, azath

i

opr

i

ne,

i

nterferon-

α

,

a

i

med

at pr

i

mary

i

ntervent

i

on

i

n the aet

i

ology o

r

p

athomechanism of liver disease

.

4.

S

econdar

y

l

i

ver thera

p

eut

i

cs:

e

.

g

.

f

at-so

l

u

bl

e

vi

tam

i

ns

i

n

i

mpend

i

ng def

i

c

i

ency states, drugs t

o

reduce portal hypertens

i

on, substances to rel

i

eve

h

yp

erammoniaemia, aimed at secondar

yp

reven-

t

ion of the various se

q

uelae of liver disease

.

Tab. 40.3:

C

ategories of liver therapeutic agent

s

3.6 Act

i

ve substance

s

F

or several

y

ears,

(

ne

g

ative

)

claims a

pp

eared in the

p

res

s

stat

i

n

g

that the

p

harmaceut

i

cal market was over

-

Treatment o

fl

iver

d

isease

s

saturated w

i

th more than 600 l

i

ver preparat

i

ons

.

A

lthough the originator of this claim was not identified

,

t

his uto

p

ian number made the rounds. • In fact, there

are mere

ly

2

5 substances or

g

rou

p

s of substance

s

(

o

f

chem

i

cal or plant or

i

g

i

n) l

i

sted

i

n the pharmacopoe

i

a.

Here, the various preparations containing the same sub-

stance are numbered se

p

aratel

y

, which

g

ives a total o

f

90

ⴚ

100 l

i

sted

p

re

p

arat

i

on

s

.

•It

i

s

i

rres

p

ons

i

ble tha

t

some “l

i

ver therapeut

i

cs” st

i

ll have an a

l

co

h

o

l

conten

t

of

2

5

⫺

66 vol.% (particularly homoeopathic and phyto

-

t

hera

p

eutic remedies

)

.

(

s.

p

.64

)

Althou

g

h the ofte

n

q

uant

i

tat

i

vel

y

low

i

ntake of alcohol

i

na

p

re

p

arat

i

o

n

may be “harmless” (even “3 t

i

mes da

i

ly”),

i

tw

i

ll usually

cause a relapse in an abstinent alcoholic

.

In principle

,

th

ereisno

j

usti

f

ia

bl

e argument

f

or

k

eeping t

h

ea

l

co

h

o

l

content in a

h

e

p

ato

l

ogica

lp

re

p

aration

!

Some dru

g

s with

sp

ecial indications

a

r

e used

in liv

e

r

d

i

s-

e

ases or in certain com

p

lications. The

y

are not found in

t

he s

p

ec

i

al cate

g

or

y

of l

i

ver thera

p

eut

i

cs

(p

harmaco-

poe

i

a), but are l

i

sted accord

i

ng to the

i

rma

i

n

i

nd

i

cat

i

on.

Treatment with some of these active substances ma

y

be

accom

p

anied b

y

side effects.

(

s. tab. 40.4

)

C

hem

i

cal substances (or

g

rou

p

s)

1

.

AA

o

f

t

h

eureac

y

c

l

e

2. Beta blockers

3.

Bil

eac

i

ds

4

.BC

AA

5. Deferoxam

i

ne

6. D-pen

i

c

i

llam

i

n

e

7.

Di

u

r

et

i

cs

8

. Glucocorticoids

9. Haemar

gi

nate

10. Immunosuppressants

11

.

Imm

u

n

ost

im

u

l

a

n

ts

12

.

L

actulose

13. Nucleos

i

de analogue

s

14. S-adenosyl-L-meth

i

on

i

n

e

15.

S

omatostati

n

16. S

p

ironolacton

e

17. V

i

rustat

i

c

s

18. V

i

tam

i

ns (

A

⫺

K

)

19

.

Zin

c

Ph

y

tothera

p

eut

i

ca

g

ents (or

g

rou

p

s

)

1. Colch

i

c

i

n

e

2. Essent

i

al phosphol

i

p

i

d

s

3. Gl

y

c

y

rrhizi

n

4

. Sil

y

marin

5

.Var

i

ous herbal preparat

i

on

s

Ta

b

.

4

0.

4

: Act

i

ve chem

i

cal substances (or groups) and phytothera-

p

eut

i

ca

g

ents used

i

n some l

i

ver d

i

seases or the

i

r com

p

l

i

cat

i

ons

Acti

v

e substa

n

ces

w

ith

p

roven efficac

y

in he

p

atolo

gy

a

r

e

o

n

l

ya

d

ministere

d

as

“

treatment

”

an

d

not as

“l

iver protec-

8

77

tion” (apart from the prophylactics mentioned above

)

.

T

hese active substances are used in patients when,

accordin

g

to the dia

g

nosed disease and the clinical an

d

p

harmacolo

gi

cal results, the

y

are actuall

yi

nd

i

cated.

•

Thus, it is the existing liver disease and/or complication

and not the medication budg et or the patient’ s wishes whic

h

d

eci

d

es t

h

et

h

era

p

eutic in

d

ication.

•

An

y

thin

g

else would

g

oa

g

a

i

nst the

p

r

i

nc

ip

les of a

p

h

y

s

i

c

i

an or be uneconom-

i

cal, and legally problemat

i

c

i

n

i

nd

i

v

i

dual cases

.

T

he second d

i

mens

i

on of controlled stud

i

es

,

“t

i

me”

,

is

frequently g

i

ven

i

nsuff

i

c

i

ent cons

i

derat

i

on

i

n evaluat

i

n

g

therapeutic results. In fact, it is only possible to asses

s

w

h

et

h

e

r

t

h

e substa

n

ces used

in

c

hr

o

ni

c

liv

e

r

d

i

sease

h

ave the re

q

u

i

red eff

i

cac

y

after an ade

q

uate treatmen

t

p

er

i

od. In the drug therapy of pat

i

ents w

i

th chron

i

cl

i

ver

disease as carried out by the clinician and general prac-

titioner, evaluation

p

eriods invariabl

y

extend over sev

-

e

ral

y

ears. In such cases,

p

os

i

t

i

ve or ne

g

at

i

ve results can

be obta

i

ned “emp

i

r

i

cally”, but because they are not

“statistically” confirmed, they are not “provable”. I

n

this context as well,

•

emp

i

r

i

c

i

s

m

•

i

ntu

i

t

i

o

n

•

l

o

g

ic

ma

y

diver

g

e

(

s.

p

. 873

)

, so that statistics, which as such

are

i

nd

i

spensable, may

i

ndeed prove to be an obstacle.

P

erhaps the expectat

i

ons or requ

i

rements of “l

i

ver ther

-

apy” are too h

i

gh. W

i

th regard to other organs and the

ir

r

es

p

ective diseases, established medication often does no

t

r

eall

y

achieve a “cure”, but merel

y

“functional im

p

rove-

ments” (e.g. recompensat

i

on,

i

nh

i

b

i

t

i

on of progress

i

on

,

s

tab

i

l

i

zat

i

on

in

everyday l

i

fe

,

i

mprovement

i

n qual

i

ty of l

i

fe,

r

ehabilitation

)

.In

p

rinci

p

le, these full

y

acce

p

table thera

py

aims a

pp

l

y

to the treatment of liv

e

r

d

i

s

eases as

w

ell.

3.7 Dose ad

j

ustment of med

i

cament

s

L

iv

e

r

a

n

d

m

ed

i

ca

m

e

n

ts a

r

e

in

te

rr

e

l

ated

in

t

hree wa

y

s

:

1. Med

i

cat

i

o

n

inducing

li

ver d

i

seases

2.

M

ed

i

cat

i

on

for

l

iv

e

r

d

i

seases

3.

M

ed

i

cat

i

on

changed by

l

iv

e

r

d

i

seases

Apart from the k

i

dneys, the l

i

ver

i

s the most

i

mportan

t

excretory organ for drugs. In contrast to other mech

-

a

nisms of dru

g

elimination, which are relativel

y

wel

l

u

n

d

erstoo

d

,

li

ver metabol

i

s

m

o

fd

ru

g

s

h

as

p

rove

d

extremely compl

i

cated. (s. pp 5

6

⫺

60)

B

iotransformation

is influenced by variable and non-variable factors unde

r

p

h

y

siolo

g

ical and

p

atholo

g

ical conditions.

(

s. tab. 3.18

)

•

C

han

g

es

i

n

p

harmaceut

i

cal

p

re

p

arat

i

on

s

are alterat

i

on

s

i

n the respect

i

ve propert

i

es wh

i

ch occur due to the d

i

s

-

turbed metabolization function of the liver cells and

/

o

r

he

p

atic blood flow secondar

y

to liver disease. Addition

-

a

ll

y

, dru

g

metabol

i

sm ma

y

be drast

i

call

y

mod

i

f

i

ed b

y

Ch

a

p

ter 4

0

c

oex

i

st

i

ng hypoalbum

i

naem

i

a or cholestas

i

s. L

i

ver d

i

s

-

eases do not only affect the elimination parameters (e.g

.

half-life, clearance

)

, but also absor

p

tion

(

e.

g

. bioavail

-

a

b

i

l

i

t

y)

and d

i

str

i

but

i

on of the dru

gi

n the bod

y

. A fur-

ther factor are the

i

nteract

i

ons of certa

i

n drugs w

i

t

h

receptors at the site of action (e.g. increased sensitivit

y

of the brain to diaze

p

am in cirrhosis

p

atients

)

. Biotoxo

-

m

etabol

i

tes and l

ipi

d

p

erox

i

dat

i

on, wh

i

ch are not nor-

m

ally typ

i

cal of a certa

i

n med

i

cament, must also be

a

nticipated. • In principle, a

dose

r

educt

i

o

n

s

h

ou

l

dbe

c

onsidered in severe and chronic liver disease, es

p

eciall

y

when the med

i

cament

i

s used re

g

ularl

y

. On the other

hand

,a

d

ose increase may be requ

i

red

i

n

i

.v. adm

i

n

i

stra-

tion owing to reduced hepatic blood flow and usin

g

m

edication with a hi

g

h elimination rate. • Disturbe

d

d

ru

g

metabol

i

sm ma

y

be further a