Lecture Notes in Mathematics 2214

Saeed Zakeri

Rotation Sets

and Complex

Dynamics

Lecture Notes in Mathematics 2214

Editors-in-Chief:

Jean-Michel Morel, Cachan

Bernard Teissier, Paris

Advisory Board:

Michel Brion, Grenoble

Camillo De Lellis, Zurich

Alessio Figalli, Zurich

Davar Khoshnevisan, Salt Lake City

Ioannis Kontoyiannis, Athens

Gábor Lugosi, Barcelona

Mark Podolskij, Aarhus

Sylvia Serfaty, New York

Anna Wienhard, Heidelberg

Saeed Zakeri

Rotation Sets and Complex

Dynamics

123

Saeed Zakeri

Department of Mathematics

Queens College of CUNY

Queens, NY

USA

Department of Mathematics

Graduate Center of CUNY

New York, NY

USA

ISSN 0075-8434 ISSN 1617-9692 (electronic)

Lecture Notes in Mathematics

ISBN 978-3-319-78809-8 ISBN 978-3-319-78810-4 (eBook)

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-78810-4

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018939069

Mathematics Subject Classification (2010): 37E10, 37E15, 37E45, 37F10

© Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature 2018

This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of

the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation,

broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information

storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology

now known or hereafter developed.

The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication

does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant

protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use.

The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book

are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or

the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any

errors or omissions that may have been made. The publisher remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional

claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Printed on acid-free paper

This Springer imprint is published by the registered company Springer International Publishing AG part

of Springer Nature.

The registered company address is: Gewerbestrasse 11, 6330 Cham, Switzerland

Preface

For an integer d ≥ 2, let m

d

: R/Z → R/Z denote the multiplication by d map

of the circle defined by m

d

(t) = dt (mod Z).Arotation set for m

d

is a compact

subset of R/Z on which m

d

acts in an order-preserving fashion and therefore has

a well-defined rotation number. Rotation sets for the doubling map m

2

seem to

have first appeared under the disguise of Sturmian sequences in a 1940 paper of

Morse and Hedlund on symbolic dynamics [17] (the equivalence with the rotation

set condition was later shown by Gambaudo et al. [10] and Veerman [28]). Fertile

ground for their comeback was provided half a century later by the resurgence

of the field of holomorphic dynamics. For example, in the early 1990s Goldberg

[11] and Goldberg and Milnor [12] studied rational rotation sets in their work on

fixed point portraits of complex polynomials. The main result of [11] was later

extended by Goldberg and Tresser to irrational rotation sets [13]. Around the same

time, Bullett and Sentenac investigated rotation sets for the doubling map and their

connection with the Douady–Hubbard theory of the Mandelbrot set [7](seeFig.1

for an illustration of this link). Aspects of this work were generalized to arbitrary

degrees a decade later by Blokh et al. who in particular gave recipes for constructing

a rotation set for m

d+1

from one for m

d

and vice versa [2]. More recently, Bonifant,

Buff, and Milnor used rotation sets for the tripling map m

3

in their work on antipode-

preserving cubic rational maps [4]. In an entirely different context, rational rotation

sets appear in McMullen’s study of the space of proper holomorphic maps of the

unit disk [19]; they play a role analogous to simple closed geodesics on compact

hyperbolic surfaces.

This monograph presents the first systematic treatment of the theory of rotation

sets for m

d

in both rational and irrational cases. Our approach, partially inspired

by the ideas in [4], has a rather geometric flavor and yields several new results on

the structure of rotation sets, their gap dynamics, maximal and minimal rotation

sets, rigidity, and continuous dependence on parameters. This “abstract” part is

supplemented with a “concrete” part which explains how rotation sets arise in the

dynamical plane of complex polynomial maps and how suitable parameter spaces of

such polynomials provide a complete catalog of all rotation sets of a given degree.

v

vi Preface

5

/

31

9

/

31

10

/

31

18

/

31

20

/

31

+

1

/

2

5

/

31

9

/

31

10

/

31

18

/

31

20

/

31

+

1

/

2

=

2

/

5

=

(

√

5

−

1

)

/

2

0

0

ω

ω

ω

ω

θθ

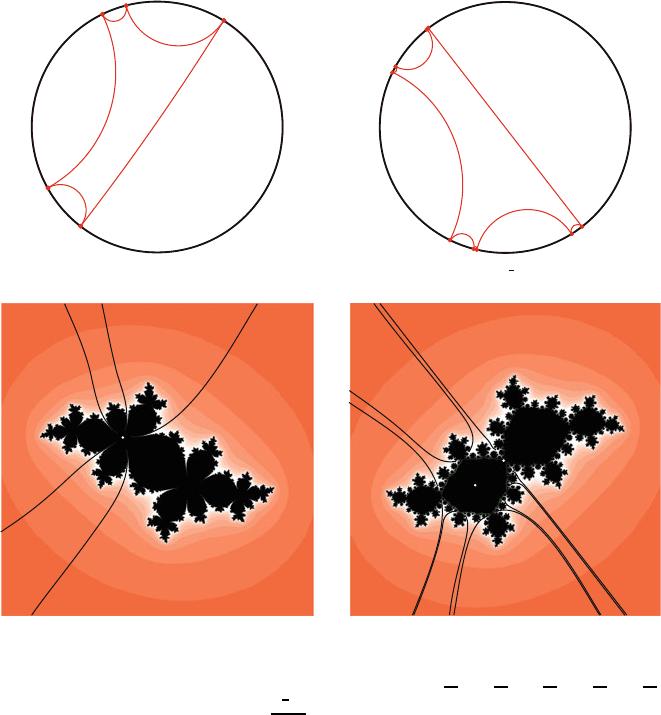

Fig. 1 For each 0 ≤ θ<1 the doubling map t → 2t(mod Z) has a unique minimal invariant

set X

θ

⊂ R/Z of rotation number θ which is a period orbit if θ is rational and a Cantor set

otherwise. Top left: The case θ = 2/5whereX

θ

is the 5-cycle

5

31

→

10

31

→

20

31

→

9

31

→

18

31

.

Top right: The golden mean case θ =

√

5−1

2

where the Cantor set X

θ

is the closure of the orbit

of ω ≈ 0.35490172 .... According to Douady and Hubbard, the “rotation set” X

θ

is related to the

external rays of the corresponding quadratic map z → e

2πiθ

z + z

2

(shown in the bottom row) as

well as the parameter rays that land on the boundary of the main cardioid of the Mandelbrot set.

See Sect. 5.3 for details

Here is an outline of the material presented in this monograph:

Chapter 1 provides background material on the dynamics of degree 1 monotone

maps of the circle. Given such a map g : R/Z → R/Z, its Poincaré rotation

number ρ(g) is constructed using a Dedekind cut approach that quickly leads

to basic properties of the rotation number and how it essentially determines the

asymptotic behavior of the orbits of g. These orbits converge to a cycle if ρ(g)

is rational and to a unique minimal Cantor set if ρ(g) is irrational. A key tool in

understanding this dichotomy is the semiconjugacy between g and the rigid rotation

r

θ

: t → t + θ(mod Z) by the angle θ = ρ(g). This semiconjugacy is also utilized

Preface vii

in studying the existence and uniqueness of invariant probability measures for g:

If ρ(g) is rational, every such measure is a convex combination of Dirac measures

supported on the cycles of g, while if ρ(g) is irrational, there is a unique invariant

measure supported on the minimal Cantor set of g.

Chapter 2 introduces rotation sets for the map m

d

and develops their basic

properties. A rotation set for m

d

is a non-empty compact set X ⊂ R/Z, with

m

d

(X) = X, such that the restriction m

d

|

X

extends to a degree 1 monotone map

of the circle. The rotation number of X, denoted by ρ(X), is defined as the rotation

number of any such extension. We refer to X as a rational or irrational rotation

set according as ρ(X) is rational or irrational. Understanding X is facilitated by

studying the dynamics of the complementary intervals of X called its gaps.A

gap I is labeled minor or major according as m

d

|

I

: I → m

d

(I ) is or is not a

homeomorphism, and the multiplicity of I is the number of times the covering map

m

d

wraps I around the circle. Counting multiplicities, X has d − 1 major gaps,

a statement reminiscent of the fact that a degree d polynomial has d − 1 critical

points. Major gaps completely determine a rotation set and the pattern of how they

are mapped around can be recorded in a combinatorial object called the gap graph.

Next, we study maximal and minimal rotation sets. Maximal rotation sets for

m

d

are characterized as having d − 1 distinct major gaps of length 1/d.A

rational rotation set may well be contained in infinitely many maximal rotation sets.

By contrast, we show that an irrational rotation set for m

d

is contained in at most

(d − 1)! maximal rotation sets. Minimal rotation sets are cycles in the rational case

and Cantor sets in the irrational case. We prove that a rational rotation set contains

at most as many minimal rotation sets as the number of its distinct major gaps. As

a special case, we recover Goldberg’s result in [11] according to which a rational

rotation set for m

d

contains at most d −1 cycles. On the other hand, every irrational

rotation set is easily shown to contain a unique minimal rotation set.

Chapter 3 offers a more in-depth study of minimal rotation sets by presenting a

unified treatment of the deployment theorem of Goldberg and Tresser. Suppose X

is a minimal rotation set for m

d

with the rotation number ρ(X) = θ = 0. Then

X is a q-cycle (i.e., a cycle of length q)ifθ = p/q in lowest terms and a Cantor

set if θ is irrational. The natural measure on X is the unique m

d

-invariant Borel

probability measure μ supported on X.Thecanonical semiconjugacy associated

with X is a degree 1 monotone map ϕ : R/Z → R/Z, whose plateaus are precisely

the gaps of X, which satisfies ϕ ◦ m

d

= r

θ

◦ ϕ on X. It is related to the natural

measure by ϕ(t) = μ[0,t] (mod Z). The covering map m

d

has d − 1 fixed points

u

i

= i/(d − 1)(mod Z).Thedeployment vector of X is the probability vector

δ(X) = (δ

1

,...,δ

d−1

) where δ

i

= μ[u

i−1

,u

i

). Note that qδ(X) ∈ Z

d−1

if θ is

rational of the form p/q.

The deployment theorem asserts that given any θ and any probability vector δ ∈

R

d−1

that satisfies qδ ∈ Z

d−1

if θ = p/q, there exists a unique minimal rotation

set X = X

θ,δ

for m

d

with ρ(X) = θ and δ(X) = δ. The rational case of this

theorem that appears in [11] and its irrational case proved in [13] are treated using

very different arguments. By contrast, we provide a proof that reveals the nearly

viii Preface

identical nature of the two cases. The key tool in our unified treatment is the gap

measure

ν =

d−1

i=1

∞

k=0

d

−(k+1)

1

σ

i

−kθ

,

where σ

i

= δ

1

+···+δ

i

and 1

x

denotes the unit mass at x.Thisisanatomic

measure supported on the union of at most d − 1 backward orbits of the rotation

r

θ

. The general idea is that the gap measure can be used to construct the “inverse”

of the canonical semiconjugacy of X and therefore X itself. This measure makes

a brief appearance in an appendix of [13], but its real power is not nearly utilized

there. In addition to its theoretical role, the gap measure turns out to be a highly

effective computational gadget.

Chapter 3 also includes a fairly detailed discussion of finite rotation sets, namely,

unions of cycles that have a well-defined rotation number. Let C

d

(p/q) denote the

collection of all q-cycles under m

d

with rotation number p/q. According to the

deployment theorem, C

d

(p/q) can be identified with a finite subset of the simplex

Δ

d−2

={(x

1

,...,x

d−1

) ∈ R

d−1

: x

i

≥ 0and

d−1

i=1

x

i

= 1} with

q+d−2

q

elements. A collection of cycles in C

d

(p/q) are compatible if their union forms

a rotation set. In [19], McMullen proposes that C

d

(p/q) can be identified with

the vertices of a simplicial subdivision Δ

d−2

q

of Δ

d−2

, where each collection of

compatible cycles corresponds to the vertices of a simplex in Δ

d−2

q

. We provide

a justification for this geometric model; in particular, for each x ∈ Δ

d−2

our

proof gives an explicit algorithm for finding a simplex in Δ

d−2

q

that contains x.

The subdivision Δ

d−2

q

is different from (and in a sense simpler than) the standard

barycentric subdivision and could perhaps be of independent interest in applications

outside dynamics.

In Chap.4, we give sample applications of the results of Chaps. 2 and 3,

especially the deployment theorem. For example, we show that every admissible

graph without loops can be realized as the gap graph of an irrational rotation set.

We also study the dependence of the minimal rotation set X

θ,δ

on the parameter

(θ, δ). We prove that the map (θ, δ) → X

θ,δ

is lower semicontinuous in the

Hausdorff topology, and it is continuous at some parameter (θ

0

,δ

0

) if and only

if X

θ

0

,δ

0

is exact in the sense that it is both minimal and maximal. We provide a

characterization of exactness which shows that the set of such parameters has full

measure in (R/Z) × Δ

d−2

.

As another application, we use the gap measure to compute the leading angle ω

of X = X

θ,δ

, that is, the smallest angle when X is identified with a subset of (0, 1):

ω =

1

d − 1

ν(0,θ]+

N

0

d − 1

=

1

d − 1

d−1

i=1

0<σ

i

−kθ≤θ

d

−(k+1)

+

N

0

d − 1

.

Preface ix

Here, N

0

≥ 0 is the number of indices i with σ

i

= 0. The formula gives an explicit

algorithm for computing the base-d expansion of the angle (d − 1)ω, which has

an itinerary interpretation in the context of polynomial dynamics. We exploit the

leading angle formula in the low-degree cases d = 2andd = 3tocarryouta

detailed analysis of the structure of minimal rotation sets under the doubling and

tripling maps.

Chapter 5 explores the link between rotation sets and complex polynomial maps.

After a brief review of the basic definitions in polynomial dynamics, we explain

how an indifferent fixed point of a polynomial of degree d determines a rotation set

under m

d

. More precisely, the angles of the dynamic rays that land on a parabolic

point or on the boundary of a “good” Siegel disk define a rotation set X with

ρ(X)=θ,wheree

2πiθ

is the multiplier of the parabolic point or the center of the

Siegel disk. In the parabolic case, this statement is well known and goes back to the

work of Goldberg and Milnor [12]. The Siegel case, while similar in spirit, is trickier

because of the possibility of rays accumulating but not landing on the boundary. The

“good” Siegel disk assumption refers to a limb decomposition hypothesis, similar

to Milnor’s in [22], which allows us to prove the required landing statements (this

hypothesis is weaker than local connectivity of the Julia set and presumably holds

for Lebesgue almost every θ). The deployment vector δ(X) can be recovered from

the internal angles of the marked roots on the boundary of the Siegel disk, as seen

from its center.

These general remarks are illustrated in greater detail in two low-degree families

of polynomialmaps. According to Douady and Hubbard, the combinatorial structure

of the Mandelbrot set (specifically, the boundary of the main cardioid and the limbs

growing from it) catalogs all rotation sets under the doubling map m

2

(see [9]

and [20]). We give a brief account of this in a section on the quadratic family,

setting the stage for the simplest higher degree example, namely, the family of

cubic polynomials with an indifferent fixed point of a given rotation number. This

one-dimensional slice was studied in [30] in the irrational case and has been the

subject of investigations by others (see for example [6]). There are indeed intriguing

connections between rotation sets under the tripling map m

3

and this cubic family.

Fix 0 <θ <1 and consider the space of monic cubic polynomials with a fixed

point of multiplier e

2πiθ

at the origin. Each such cubic has the form f

a

: z →

e

2πiθ

z + az

2

+ z

3

for some a ∈ C,wheref

a

and f

−a

are affinely conjugate under

the involution z →−z.Theconnectedness locus

M

3

(θ) ={a ∈ C : The Julia set J(f

a

) is connected}

is compact, connected, and full (compare Figs. 5.8 and 5.10). Outside M

3

(θ) exactly

one critical point of f

a

escapes to ∞ and the Böttcher coordinate of the escaping

co-critical point gives a conformal isomorphism CM

3

(θ) → CD which can

be used to define the parameter rays of M

3

(θ).

When θ is rational of the form p/q in lowest terms, the set X

a

of angles of

dynamic rays that land at the parabolic point 0 is a rotation set under tripling

with ρ(X

a

) = p/q.Thereare2q + 1 possibilities for X

a

parametrized by their