Exploring the Orthogonal Relationship

between Controlled and Automated Processes

in Skilled Action

John Toner

1

& Aidan Moran

2

#

The Author(s) 2020

Abstract

Traditional models of skill learning posit that skilled action unfolds in an automatic

manner and that control will prove deleterious to movement and performance profi-

ciency. These perspectives assume that automated processes are characterised by low

levels of control and vice versa. By contrast, a number of authors have recently put

forward hybrid theories of skilled action which have sought to capture the close

integration between fine-grained automatic motor routines and intentional states.

Drawing heavily on the work of Bebko et al. (2005) and Christensen et al. (2016),

we argue that controlled and automated processes must operate in parallel if skilled

performers are to address the wide range of challenges that they are faced with in

training and competition. More specifically, we show how skilled performers use

controlled processes to update and improve motor execution in training contexts and

to stabilise performance under pressurised conditions.

Keywords Control

.

Automaticity

.

Continuous improvement

.

Expertise

.

Skilled action

1 Introduction

Skilled action in sport is widely believed to be facilitated by an absence of conscious

attention to the mechanics of one’s movements during skill execution (see Masters and

Maxwell, 2008, for a review). Anecdotal evidence to support this idea abounds in sport.

Review of Philosophy and Psychology

https://doi.org/10.1007/s13164-020-00505-6

* John Toner

john.toner@hull.ac.uk

Aidan Moran

aidan.moran@ucd.ie

1

Department of Sport, Health and Exercise Sciences, University of Hull, Cottingham Road,

Hull HU6 7RX, UK

2

School of Psychology, University College Dublin, Belfield, Dublin 4, Ireland

For example, when the triple-major champion golfer Padraig Harrington won the 2007

open Championship in Carnoustie after a play-off against Sergio Garcia, he described

his thoughts as he prepared for his final putt: ‘no conscious effort whatsoever went into

that putt. There were no thoughts about ‘this is for the Open’… I stroked it in’ (cited in

Jones, 2007, p. 12). Supporting this idea, evidence from the experimental psychological

literature would suggest that engaging in any form of conscious control will hamper

athletic performance. To illustrate, performance pressure may lead athletes to become

increasingly conscious of their movement and suffer a concomitant breakdown of

automated skills (Beilock et al., 2002;Masters&Maxwell,2008) – a phenomenon

popularly known as ‘paralysis-by-analysis’ (Beilock, 2010). More generally, a consid-

erable body of experimental evidence highlights the debilitating effect of ‘conscious

processing’ (or paying attention to one’s action during motor skill execution) on skilled

athletes’ movement and performance (e.g., Beilock and Carr, 2001).

These findings support the predictions made by a number of highly influential

models of skill acquisition which place controlled and automated processing at opposite

ends of a single continuum (e.g., Shiffrin and Schneider, 1977). According to this view,

processing becomes less deliberate and effortful (i.e., controlled) as a skill becomes

more automatized. However, we argue that this perspective is unable to account for the

wide range of empirical evidence which indicates that performance continues to be

mediated by controlled processes even after one attains expertise. We seek to address

this misunderstanding by presenting a model which explains how controlled and

automated processes may emerge concurrently and how they must operate in a

synergistic fashion if experts are to overcome the challenges they face in seeking to

maintain performance proficiency over long timescales. We start by pointing to some

of the weaknesses associated with linear or serial models of skill learning and the

experime ntal paradigms used by studies they have spawned. Following this, we

introduce a model of skilled action which explains how controlled and automatic

processes operate in an orthogonal manner. Next, we elucidate what is meant by the

term “controlled processes” before considering how expert performers will often revert

to controlled processing when confronted by “bodily crises” andaspartofongoing

attempts to maintain or update their bodily capacities. We then consider the role

controlled processes play during peak performance states and detail some of the

strategies athletes might use to induce clutch performances. We conclude by briefly

discussing the role metacognition plays in allowing expert performers to identify and

apply situationally appropriate modes of control.

At first glance, the body of empirical evidence which has explored the role con-

sciousness plays in expert action would seem to suggest that conscious control will

inevitably prove to be a hazardous activity for athletes to engage in during performance.

But does this evidence tell the whole story? To answer this question, we need to delve

deeper into the issues involved. One of the oldest distinctions in cognitive psychology

is that between mental processes that require conscious control and those that do not.

For example, William James (1892) distinguished between ‘willed’ actions (which

involve a conscious component in the form of a ‘fiat, mandate or expressed consent’,p.

335) and ‘ideo-motor’ actions (where the person is ‘aware of nothing between the

conceptions and the execution’, p. 335). This distinction surfaced again in cognitive

psychology in the 1970s when researchers differentiated between ‘controlled’ process-

es (e.g., reading for comprehension), which are typically portrayed as being effortful,

J. Toner, A. Moran

conscious, slow and error-prone and ‘automatic’ processes (e.g., writing one’sname),

which are regarded as being unintentional, effortless, involuntary, unconscious and fast

(e.g., see Shiffrin and Schneider, 1977). In an effort to account for certain subsequent

empirical anomalies (e.g., the fact that some automatic processes are amenable to

consciousness and can be controlled intentionally whereas others are not; Sternberg

and Sternberg, 2009), ‘dual process’ views of attention (e.g., Evans and Stanovich,

2013) have given way to a more fine-grained analysis of this construct. For example, a

number of researchers have proposed hybrid theories of skilled action which have

sought to capture the synthesis between cognitive and automatic processes (e.g.,

Mylopoulos and Pacherie, 2017).

And yet, despite the emergence of these latter perspectives, dual process views of

skill learning (which place cognitive processes on a continuum ranging from fully

controlled to fully automatic) continue to hold sway in the skill acquisition/sport

psychology literature (e.g., Furley et al., 2015). Before considering the utility of hybrid

theories, however, we should provide a brief overview of the dual process view and

consider how this perspective has shaped current conceptualisations of skilled action.

Dual process views typically portray learning as involving a gradual reduction of

cognitive resources as one acquires an increasing level of control over motor execution.

Take, for example, Fitts and Posner’s(1967) highly influential model of skill acquisi-

tion which postulates that learning occurs in three linear stages. In the initial cognitive

stage, agents draw on explicit rules to consciously guide task performance. This will

inevitably require them to experiment with different strategies to see which brings them

closer to a movement goal (Wulf, 2007). The associative stage is characterised by

increasingly consistent and economical movement patterns. In a final autonomous

stage, movement production is fluent, effortless, immune to dual task interference,

and requires little cognitive control. Similar to a number of other influential models of

skill learning (e.g., Anderson’s, 1982, Adaptive Control of Thought Theory), Fitts and

Posner theorise that controlled and automatic processes reside at opposite ends of a

single continuum. According to this view, low automaticity is associated with high

levels of control and vice versa.

Another feature common to dual process views is the belief that automaticity is a

defining feature of optimal performance while control is associated with the degrada-

tion of motor execution (Masters and Maxwell, 2008). Advocates of this perspective

often present the phenomenon of “expert induced amnesia” (when asked to recall how

they have performed a task experts provide impoverished accounts containing little

recollection of the episodic ‘rules’ that guided their action; see Beilock et al. 2002)as

prima facie evidence that skilled actions are governed by automatic processes. In a

number of experimental studies, skilled performers have reported few explicit episodic

rules relating to the execution of a highly practiced motor skill (e.g., Beilock et al.

2002). Unfortunately, the experimental paradigm adopted by many of these studies

presents performers with conditions that are static and largely unchanging (take the

standard putting task which is such a popular means of testing motor control in

laboratory studies; see Christensen et al., 2015, for a detailed critique). As a result,

the tasks are hampered by a lack of real-world complexity – key features that one

would find in a naturalistic setting (e.g., changes in environmental conditions or high

levels of performance pressure). It is perhaps unsurprising that ‘experts’ in Beilock’s

study appeared amnesiac when asked to report what they had focused on when

Exploring the Orthogonal Relationship between Controlled and...

performing the putting task. Once a feel for the pace of the putt had been established,

motor execution could be initiated and run to completion without any need for the

participant to supervise elements of performance or to alter any movement parameters

(e.g., timing, force etc).

In summary, task difficulty is likely to have a significant influence on the type of

processing engaged in by the skilled performer. Simple laboratory tasks might reveal

how automated processes underpin skilled performance when conditions are static and

predictable but they do not shed light on the forms of control that might be required

when experts face “challenging-but-normal conditions” (Christensen et al., 2016).

Additionally, there will often be proponents or properties of a task which have not

been automated and this leaves the performer with little choice but to maintain control

over task execution (Carr, 2015). This would suggest that automated and controlled

processes are actually tightly integrated rather than acting independently of each other.

In one of the few empirical studies to explore the latter possibility, Bebko et al. (2005)

examined the evolution of controlled and automatic processing in a three-ball bounce

juggling task. This task required participants to bounce a ball on the floor alternately

from one hand to the other in a V-shape (at least one of the three balls was always in

motion). A control task introduced two variations to the juggling task that involved

changing the ball weights, sizes and textures in one task whilst using an inclined

surface or a flat floor in the other. The basic parameters of the tasks remained the same

(i.e., bounce juggling). Control over these adaptations emerged along with the devel-

opment of automatized skills on the main task. On the basis of these findings, Bebko

et al. (2005) presented a model in which controlled and automatic processes emerge

orthogonally. According to the authors, “control processes refer to processes that

enable adaptation within cognitive schema or motor programs, rendering the programs

flexible so that one can respond to changing external or internal demands while still

executing the same behaviour” (Bebko et al. 2005,p.474).

2 Control and Skilled Action

In the following sections, we detail various forms of control that experts might utilise

during performance. We argue that automated and controlled processes must operate

synergistically if the performer is to continue to develop their embodied capacities. In

doing so, we will delineate the different types of control skilled agents might employ in

seeking to maintain performance proficiency in the face of the huge variety of

challenges they face over their lifespan. We will focus on the interaction between

automated and controlled processes in two particular contexts (1) when performers seek

to update and improve motor execution and (2) when they attempt to stabilise perfor-

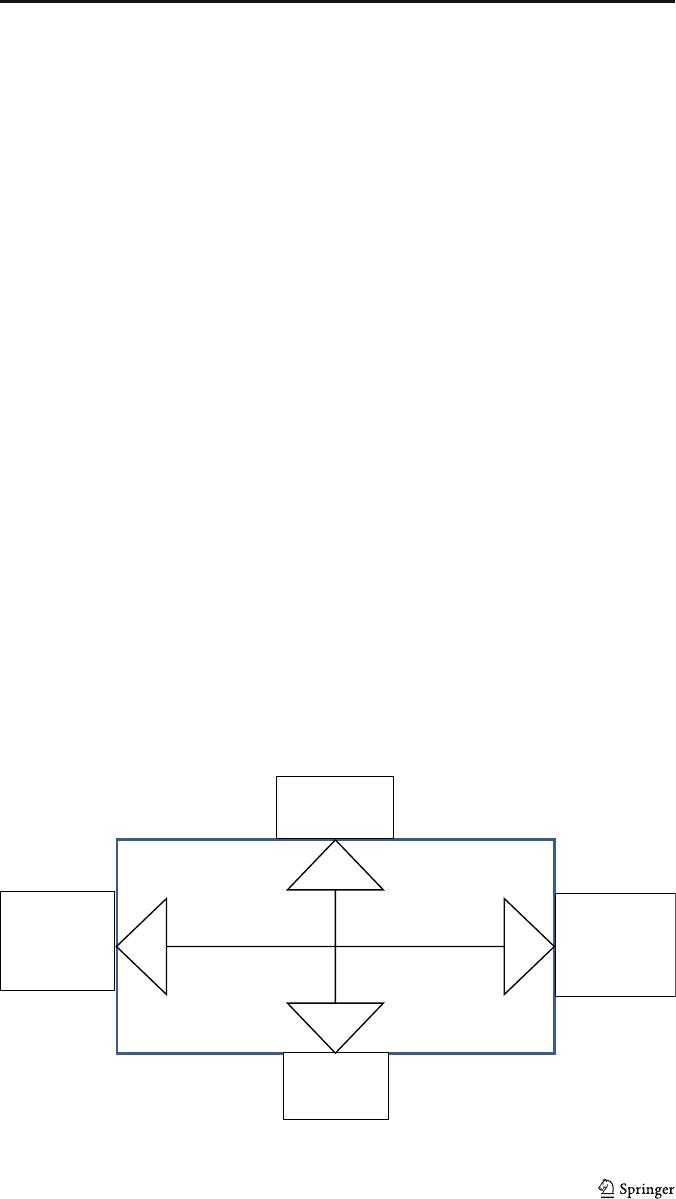

mance proficiency under pressurised conditions. We use Bebko et al.’s(2005)model–

which focuses largely on the emergence of controlled and automatic processes as

performers learn to master motor tasks - to show how the maintenance of skilled or

expert action is dependent upon these processes operating in an orthogonal fashion (see

Fig. 1). That is, rather than existing on a linear and single continuum, automaticity

exists on one continuum (ranging from nonautomatic to automatic processing) and

control refers to a separate, orthogonal continuum (ranging from low to highly con-

trolled processing). Using this model, we show how certain performance states are

J. Toner, A. Moran

characterised by these processes emerging together whilst others are characterised by

high levels of automaticity and low levels of control, and vice versa (i.e., one process

developing more quickly than the other).

Given the importance we attribute to control processes perhaps we should devote a

little more attention to explaining what is meant by the term. In this regard, Fujita et al.

(2014) argued that this term has two different meanings. On the one hand, it is defined

by the absence of the features (unintentional, unconscious, effortless) that characterise

automaticity (bearing in mind that not all automatic processes will be equally

characterised by each of these features all of the time, see Fridland, 2014). In other

words, controlled processes are simply ones that are not automatic. On the other hand,

“controlled” can be defined in terms of its capacity to foster conscious goal-pursuit.

Thus, according to Moors (2016), a process is controlled when “apersonhasagoal...

and there is a causal relation between the goal and the occurence of the desired state”

(p. 265). Such conceptualisations seem to cover higher-level goals or intentional states

(to do with planning, forethought etc) but do not account for evidence that performers

often seek to deliberately control motor execution (e.g., when they experience perfor-

mance pressure or when they attempt to alter “attenuated” movement patterns) in an

effort to maintain performance proficiency. Indeed, there is a wide range of theoretical

perspectives and empirical evidence demonstrating the important role cognitive control

plays not only in directing strategic aspects of performance but in influencing motor

execution also (see Christensen et al. 2016).

Drawing on some of this evidence, philosophers of skilled action have attempted to

present a fine-grained analysis of the types of control agents might use during the

performance of complex actions (see Fridland, 2014; Mylopoulos & Pacherie, 2017;

Shepherd, 2014 for examples). To illustrate, Christensen et al. (2016) distinguished

between three different types of control. First, they argue that strategic control involves

formulating the overall game plan one hopes to employ during a temporally extended

event (e.g., tennis match). Based on a careful evaluation of one’s technical and tactical

strengths, and those of the opponent, a tennis player might start a match with the

intention of playing largely from the back of the court. However, as the match unfolds,

High

Automaticity

(Low Effort)

High Control

(High Effort)

Low

Automaticity

(High Effort)

Low Control

(Low Effort)

Fig. 1 Orthogonal model of automatic and controlled processing in skilled action (adapted from Bebko et al. 2005)

Exploring the Orthogonal Relationship between Controlled and...

the player might realise that this tactic is being neutralised by an opponent who is

adopting a similar strategy. To address this, the player might employ situational control

whereby he or she determines what actions are suitable for the specific situational

challenge they face (if an opponent is wedded to the baseline then one may wish to

exploit this by attacking the net). Finally, implementation control involves overseeing

the execution of the actions specified by situation control. If one has decided that the

most effective strategy is to increase the frequency with which one approaches the net

then implementation control will involve automatic adjustments to parametric details of

action such as the force and direction of one’s volleys (in response, of course, to the

opponent’smovement).

Not only does received wisdom hold that automaticity underpins the fluent execu-

tion of complex skills but, in the psychological literature, control is often presented as

the enemy of embodied coping. A large volume of evidence has shown how skilled

action is disrupted when experts reinvest conscious attention in proceduralised skills

(e.g., Gray, 2004; Jackson et al. 2006). To explain these findings, self-focus models

(e.g., Masters’, 1992, conscious processing hypothesis and Beilock and Carr’s, 2001,

explicit monitoring hypothesis) have proposed that anxiety increases athletes’ level of

self-consciousness and causes them to turn attention away from goal-directed action

and inwards towards movement mechanics. As noted above, this shift to self-focused

attention is held to prompt a form of “paralysis-by-analysis” whereby athletes attempt

to gain control over automated skills. Here, proceduralised control structures that

normally operate without interruptions are broken down (or de-chunked) into a se-

quence of smaller, independent movements, in a manner representative of performance

during novice learning. If performers seek to control motor execution by drawing upon

explicit rules to manipulate the mechanics of their action during on-line skill execution

then one would expect skilled action to be disrupted – especially if the performer had

little previous experience focusing on these aspects of technique. That said, we

shouldn’t take this as evidence that all forms of control will inevitably prove deleterious

to performance proficiency.

3 Bodily “Crises”

In what follows, we seek to address this issue by discussing a number of situations (i.e.,

“crises”, continuous improvement and performance pressure) that are likely to require

flexible control of automated procedures. Let us start by considering how the emer-

gence of certain “crises” might compel the performer to employ controlled modes of

processing. The challenges faced by embodied agents who are required to execute

complex actions with extraordinary precision over many years means that conscious

reflection is a routine feature of their everyday training regimes. They must retain an

awareness of their corporeal schema to ensure that everything continues to run smooth-

ly and they have little choice but to consciously intervene – especially when they

encounter a variety of what might be termed bodily ‘crises’. According to Schilling

(2008) crises occur when ‘there develops a significant mismatch or conflict between

the social and physical surroundings in which individuals live and their biological and

bodily potentialities’ (p. 16). We argue that these crises represent a relatively ubiquitous

feature of the performance environment and present a threat to the athlete’sroutinised

J. Toner, A. Moran

ways of acting. Examples include injury, performance slumps and the senescence that

confronts the aging body. These events leave the skilled performer with little choice but

to consciously override habituated modes of action.

To do so, performers will often seek to address ‘attenuated’ movement patterns by

reinvesting conscious attention in the training context (see Toner et al. 2020). To regain

prior levels of performance, athletes in sports such as swimming and javelin throwing

have employed a variety of conscious processing strategies to restore or refine habitual

movements (Carson et al., 2014; Hanin et al., 2004). Successful cases of technical

change have involved performers becoming more consciously aware of the kinaesthetic

differences between current (problematic) and desired actions. This is a process that

often requires athletes to break down or parse proceduralised movement patterns rather

than continuing to practise in a manner which further automates or establishes them.

This is undoubtedly a highly effortful process where the performer seeks deliberately

and consciously to de-automate habitual movements – often focusing on explicit rules

and procedures that guide the execution of the movement. This state is characterized by

processing which is slow, attentionally demanding and effortful. Here, habitual actions

are broken down into separate units and this may involve freezing various degrees of

freedom in an effort to perform the desired movement. In this state, motor execution is

rigid and inflexible as the performer seeks to re-parameterize action and gain control

over movement proficiency. Considerable conscious resources are required until com-

ponents of the behavior become “chunked” into single units (motor programs,

cognitive schemata; Bebko et al. 2005). Performers undertaking this process would

be positioned in the lower left quadrant of our model (characterized by high effort, low

automaticity and low control; see Fig. 1). In summary, de-automating an undesired

movement pattern and re-automating a new movement requires a high degree of effort.

As noted above, the performer would have little control over action at this stage –

movement outcome will be inconsistent and error-strewn until the new movement is

established (see Carson et al. 2014).

4ContinuousImprovement

Whilst ‘crises’ will often prompt conscious modes of processing, we argue that skilled

performers’ are strongly motivated by a desire to master their craft (see Hardy et al.

2017) and this requires them to remain deeply attentive to embodied capacities. We

refer to this process as “continuous improvement” and suggest that it is characterized

by a desire to refine and update one’s repertoire of skills (Toner and Moran, 2014).

There is a tendency in the motor control literature to conflate performance on simplistic

laboratory tasks (which, once automatized, require little subsequent oversight) with

those requiring considerably more degrees of freedom (e.g., the golf swing) and which

are particularly susceptible to bodily crises. It is perfectly understandable why reflection

or conscious computation may be unnecessary when one is engaged in mundane

activities such as brushing one’s teeth or perhaps performing the simplistic sensorimo-

tor skills that are often tested in experimental studies. In these cases, we are likely to

have acquired an action which is adequate for the job at hand and have little reason or

motivation to consider whether a better or more efficient technique exists. Once

acquired and routinized, the action can be initiated and run to completion without the

Exploring the Orthogonal Relationship between Controlled and...

need to devote any attention to the mechanics of the movement. Skilled agents, on the

other hand, have devoted extraordinary care and attention to the development of their

embodied capacities and are heavily invested in the gradual refinement and improve-

ment of their bodily movement (see Montero, 2016).

Indeed, many seem committed to mastering their craft and this appears to be a

defining feature of continuous improvement. To illustrate, Hardy et al. (2017)com-

pared the psychosocial biographies of super-elite athletes from Olympic sports (those

who had medalled) to those of elite athletes (who had not medalled) and found that the

super elite athletes emphasised the importance of both mastery and outcome while the

elite athletes focused almost exclusively on winning. The performer who wishes to

master his/her craft has little choice but to c onsciously intervene as excessive

proceduralisation is likely to result in ‘arrested development’–where performance is

constrained and plateaus as a result (Ericsson, 2008). Furthermore, longevity in any

skill domain requires participants to keep pace with changes in rules, the introduction of

new technology, and advances in understanding as well as dealing with a range of

crises. Performers must be able to make intentional modifications to their action in

response to these challenges. Avoiding the proceduralisation of skill seems to be an

important means by which they achieve this aim (represented by high control and high

effort on our model).

5 Is Optimal Performance Fully Automatic?

While some researchers might broadly accept that experts can make intentional mod-

ifications to their action in the practice context, received wisdom holds that optimal

performance in sport is an entirely automatic process (characterised by features such as

a lack of awareness, effortless, fast etc). Indeed, the phenomenon known as “flow” is

presented as a paradigmatic example of the mindlessness of skilled action (see Dietrich,

2004). This state often accompanies optimal performances and has been characterised

by various features such as a merging of action-awareness, a loss of self-consciousness,

a sense that one is in total control over one’s performance, and the altered sense of time

(see Csikszentmihalyi, 1990). Early research on flow presented this state as involving

reduced frontal activation (indicative of a reduction in conscious processing) but more

recent findings have suggested that supervisory attentional and cognitive control

systems of the brain are highly active during flow (see Harris et al., 2017a). For

example, Ulrich et al. (2016) discovered that brain areas related to the Multiple

Demand (MD) network (which is linked to goal-directed behaviour and selective visual

attention) had higher levels of activation during a flow level of difficulty in an

arithmetic task than a harder level of difficulty. These findings would suggest that flow

states require more attentional effort than previously thought and therefore cannot be

considered fully automatic. In a study using a simulated car-racing task designed to

promote different levels of flow, Harris et al. (2017b) found that the absorption that

accompanies the flow state is based on an efficient but effortful form of attention (as

indexed by peak ratings of absorption, peak heart rate and reduced gaze variability).

These neuroscientific and experimental discoveries have been mirrored by recent

qualitative evid ence which has shown how optimal performance in sport is

characterised not by the ‘mindlessness’ that is typically associated with automated

J. Toner, A. Moran

processes but, rather, by the flexible deployment of attentional resources in order to

maintain performance proficiency under pressurised conditions. In fact, Swann et al.

(2017) research on elite athletes’ experiences of peak performance indicates that these

states are characterised by high levels of automaticity and high levels of control

(placing this type of performance state in the upper right quadrant of our model).

Interestingly, they have discovered a flow-like state which they termed “letting it

happen” and a state which was not characterised by the attentional processes one

typically associates with flow or peak performance which they termed “making it

happen”. Although these states share similar features, “making it happen” was de-

scribed as a more intense state of optimal arousal with participants experiencing a sense

of heightened and effortful concentration. This is intriguing because flow has tradition-

ally been conceptualised as involving an effortless form of attention.

“Letting it happen” seems to be associated with a gradual build-up of confidence

over time. One’s performance or the fluency of motor execution may improve incre-

mentally over practice sessions until a point where everything ‘clicks’ into place. As

performance improves and one acquires increasing control over performance, the

athlete develops the confidence to let motor execution unfold automatically. “Making

it happen”, on the other hand, is an intentional process involving a conscious decision

to increase the attentional resources that one devotes to performance. During this state,

task execution continues to unfold in an automatic manner but the performer devotes

additional cognitive resources to strategic control. This might happen when the per-

former realises that they have reached a make-or-break stage of a match/competition

(i.e., a situation in which the stakes are particularly high). As a result, the performer

must remain sensitive to any changes in the structure of a situation. This, in turn, leads

to an increased focus on the strategic aspects of task control (Christensen et al. 2016).

The process of “making it happen” bears conceptual similarity to the phenomenon of

“clutch” (which occurs when a participant in a competitive sport succeeds at a point in

competition where success or failure has a significant impact on the outcome of the contest;

Hibbs, 2010) performance in sport. Both processes are characterised by the use of effortful

attention. Evidence in support of this contention can be found in a recent study by Swann

et al. (2017) who interviewed 16 athletes from a range of sports about their subjective

experiences of clutch performances. The defining characteristics of this state included

complete and deliberate focus, intense effort (including trying harder and making a con-

scious effort), heightened awareness (including awareness of self, self-monitoring), height-

ened arousal, absence of negative thoughts,andautomaticity of skills. Interestingly, the data

from this study indicates that both automatic and controlled processes may be involved in

clutch states. In stark contrast to earlier accounts of flow/peak performance, Swann et al.’s

findings (2 017) show how performing at one’s best often requires increased effort rather

than letting things happen; conscious processing; intensity; and effortful concentration.

These athletes induced a clutch state by using self-regulatory processes to increase self-

monitoring and the effort and concentration that they devoted to performance. We argue that

flow is characterised by an increase in situational awareness which serves to establish a

cognitive and motor configuration appropriate to the context (Christensen et al.

2016).

At first glance, the argument presented above seems to contradict the widely held view

that flow states involve effortless (where our attention is held easily) rather than effortful

attention (where we must concentrate hard in order to maintain our focus). Interestingly,

although Csikszentmihalyi consistently argues that flow is reliant on automated sequences

Exploring the Orthogonal Relationship between Controlled and...

of actions he claims that effortless attention is not fully automatic in nature. Thus,

Csikszentmihalyi and Nakamua (2010) postulate that ‘it is likely that in flow a person is

more open, more alert and flexible, within the attentional structure of the activity’ (p. 186).

These authors argue that skilled actors can filter out extraneous information and focus their

attention on the complex and ambiguous stream of information that must be processed and

interpreted as the activity unfolds. In this way, they can respond to c hallenges in an

appropriate and context-sensitive manner. It is difficult to envisage how this might happen

if the agent is unable to exert control over performance – if they are ‘off-task’ or fail to

keep the intentional go al of the activity activated in consciousne ss. Flow or optimal

experience may very well involve getting caught up in the current of activity but this

doesn’t mean that performers aren’t acutely aware of the quality of their action and the

varying problems that may present themselves during the course of skill execution.

Retaining situational awareness allows them so respond in a context-sensitive manner

by exerting higher-order control over action and this appears to be precisely what happens

during clutch performances (high control and high automaticity in our model).

Peak performance states like flow or clutch are characterised by a sense of total control

over performance - involving an extremely tight integration between intentional and motor

states (Fridland, 201 7). Importantly, motor execution here is not of the brute, low-level

reflexive variety but is characterised by its variability and flexibility. Fridland (2017)

marshals a range of e vidence which contradicts the widely held view that automatized

basic action routines are ballistic (once initiated they cannot be inhibited) and invariant.If

one thinks of automated action in these latter terms then one conceives of movement

kinematics as unfolding in a fixed, rigid or predetermined way. We argue that clutch states

will only arise if the movement system possesses the flexibility to tailor parametric control

to the fine-grained structure of a situation. Skilled agents are capable of this because they

possess movement repertoires that are inherently variable (owing to physiological pro-

cesses and environmental factors) and this allows movement outcomes to be achieved in

different ways by dynamical movement systems. Here, movement variability is seen as a

key signature of adaptability (Seifert et al. 2013). Variability is believed to provide the

movement system with the flexibility required to discover coordination solutions to

“achieve the same task goal under dynamically interacting task, environmental and

personal constraints” (Chow et al. 2016, p. 37). So, the variability inherent in human

movement systems means that automatic basic actions can be adjusted in response to

contextually-contingent demands. That said, the athlete can continue to exert higher-order

control over the parametric details of action. This performance state is characterised by

high speed, high accuracy, flexible control over variations in a task and effortful attention

(represented by the top right quadrant of the model; see Fig. 1).

6 Control and Clutch Performances

Performance pressure is a ubiquitous feature of elite performers’ training and compet-

itive regime. Poor performances can often have important financial and personal

implications and this invariably places huge pressure upon athletes. In the next section

we detail various forms of control that athletes might employ in seeking to combat the

deleterious consequences of performance pressure and to produce clutch performances.

A number of studies (see Gucciardi et al., 2010;Hilletal.,2010; Oudejans et al., 2011)

J. Toner, A. Moran