Vol.:(0123456789)

1 3

European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-020-06149-7

HOW I DOIT

The nasal tent: anadjuvant forperforming endoscopic endonasal

surgery intheCovid era andbeyond

S.H.Maharaj

1

Received: 6 June 2020 / Accepted: 16 June 2020

© Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature 2020

Abstract

Purpose To propose a cost-effective reproducible barrier method to safely perform endoscopic endonasal surgery during

the Covid-19 pandemic.

Methods This manuscript highlights the use of a clear, cost-effective disposable plastic sheet that is draped as a tent over

the operating area to contain aerolization of particles. This is then connected to a suction to remove airborne particles and

thus reduce transmission of the virus.

Conclusion The use of a nasal tent is a simple and affordable method to limit particle spread during high-risk aerolisation

procedures during the Covid era and beyond.

Keywords Nasal tent; endoscopic sinus surgery· Covid-19

Background

The advent of the Covid-19 pandemic has disrupted health-

care systems and surgical procedures throughout the world.

Coronaviruses are approximately 0.125µm in size and are

frequently carried in respiratory droplets [1]. The study dem-

onstrates that COVID-19 can remain viable and infectious

for hours in aerosolized materials and for days on surfaces

[2].

Due to the high risk of viral aerolisation during proce-

dures such as endoscopic sinus surgery, a plethora of cases

have been postponed or cancelled [3].

However, it is not feasible to continue in this manner, as

the duration of the pandemic is hard to predict. There may

also be further global viral pandemics in future and thus the

otorhinolaryngology community has to now adapt to the new

normal. Mitigation strategies have included cold surgical

instrumentation, negative pressure theatres and the use of

the microdebrider [4].

The gold standard would be to create two self-contained

surgical environments (one for the aneathetized patient and

another for the theatre team) that can easily interact with

each other and not allow cross contamination.

The use of Personal protective equipment (PPE) creates

a barrier that protects the health care worker, however, it

would be easier just to isolate the patient within a three-

dimensional surgical field that would trap and remove aero-

solized particles [5].

We propose the use of a simple clear isolation plastic

sheet (160 × 200cm) nasal tent to limit aerolization during

these procedures. The cost of such a sheet varies from 4 to

8 US dollars and is quite readily available in most centres

throughout the world.

Description ofthetechnique

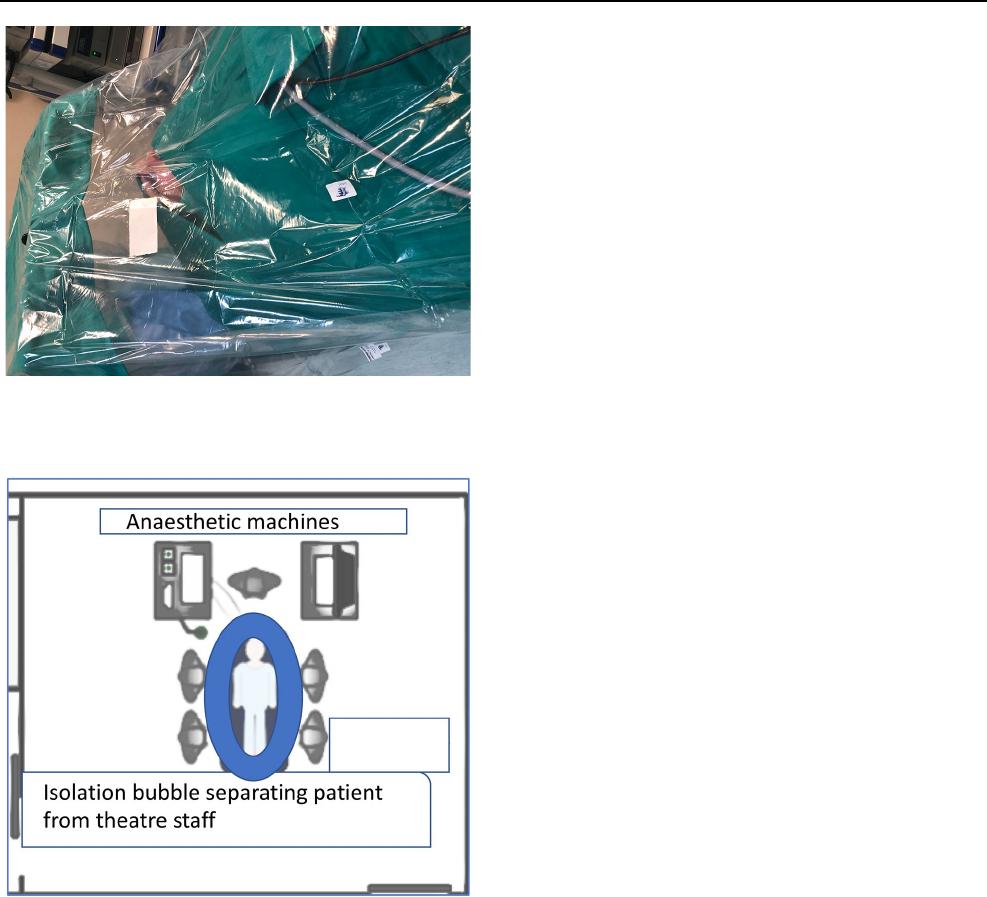

The patient is intubated with a cuffed endotracheal tube

using PPE and the video laryngoscope. The patient is posi-

tioned, a throat pack inserted and draped. An operating tray

is positioned at the cranial end of the bed 30cm above the

patients head (Fig.1).

Two openings are left for the surgeons hands and the scrub

nurse. These are inserted under the tent which then secured to

the operating table using adhesive tape along with the entire

head and torso region. A separate low flow suction unit (such

that it does not collapse the tent) is connected to the tent to

steadily remove aerosolized particles within the tent and filter

* S. H. Maharaj

Shivesh.mahara[email protected]

1

Department ofOtorhinolaryngology, University

oftheWitwatersrand, Johannesburg, SouthAfrica

European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology

1 3

it through a separate suction unit to prevent cross-contamina-

tion with the theatre filtration system (Fig.2).

Indications

Endoscopic sinonasal procedures done in the operating theatre.

Limitations

The tent is best suited for a single surgeon procedure. Once

the procedure is started there is no passing of instruments

under the tent, thus all instruments need to be selected and

set out under the tent prior to surgery.

There is a learning curve to operating under the tent.

The theatre staff still need to use full PPE.

Currently may only be used in theatre.

Further studies are required to assess the efficacy and effi-

ciency of the nasal tent.

How to avoid complications:

Theatre staff should be trained and should practice on

how to safely drape and remove the plastic without compro-

mising the integrity of the unit.

The use of diathermy and sharp instrumentation needs

to be carefully monitored so as to not damage the nasal tent

and compromise its barrier effect.

The surgery should be well planned with all members of

the team.

All surgical instruments and apparatus should be secured

into the tent prior to commencing the procedure. Once the

surgeon has placed his hands under the tent, the adhesive

tape creates a seal that prevents aerosolization into the oper-

ating theatre.

Key points

•

Pre-operative testing of surgical patients prior to endo-

nasal surgery is advised.

•

Postpone surgery in COVID-19 positive patients if pos-

sible till they recovered.

•

All emergency cases and untested patients should be

managed as positive until proven otherwise.

•

Aneasthesia and surgery should limit the degree of

aerolization of particles.

•

Cost-Effective and simple barriers may be used to isolate

the surgical field and prevent contamination of the theatre

and infection of theatre staff.

•

The nasal tent is an easy to learn and cost-effective bar-

rier that may be used to prevent viral dissemination in

theatre.

•

Further by connecting suction to the tent will the viral

particles may be safely extracted and filtered.

•

The Covid pandemic may be protracted and thus we will

have to re-think the way we perform surgery to protect

both the patient and the staff, in the current pandemic

climate and beyond.

Funding No research grant was utilized for the study conducted.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest The authors hereby declare that they have no con-

flict of interest.

Fig. 1 Nasal tent draped over the patient

Fig. 2 Diagram of the isolated patient in theatre-bubble theory

European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology

1 3

Ethical approval All procedures performed in this study involving

human participants were conducted in accordance with the ethical

standards of the Helsinki guidelines. Consent was obtained from the

patient for the use of the images.

References

1. Fehr AR, Perlman S (2015) Coronaviruses: an overview of their

replication and pathogenesis. Methods Mol Biol 1282:1–23

2. Van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Morris DH, Holbrook MG,

Gamble A, Williamson BN etal (2020) Aerosol and surface sta-

bility of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. N Engl J

Med. 382:1564–1567

3. Judson SD, Munster VJ (2019) Nosocomial transmission of

emerging viruses via aerosol-generating medical procedures.

Viruses 11:940

4. Zheng MH, Boni L, Fingerhut A (2020) Minimally invasive

surgery and the novel coronavirus outbreak: lessons learned in

China and Italy. Ann Surg 272(1):e5–e6. https ://doi.org/10.1097/

SLA.00000 00000 00392 4

5. Radonovich LJ Jr, Simberkoff MS, Bessesen MT, Brown AC,

Cummings DAT, Gaydos CA etal (2019) N95 respirators vs medi-

cal masks for preventing influenza among health care personnel:

a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 322(9):824–833

Publisher’s Note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to

jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.