Chapter 7

Catching Up on Studies Not Employment

7.1 Middle East and North Africa

1

7.1.1 Employability

In its 2015 global report, the ILO observes that in the Middle East and North Africa,

the overall level of unemployment has risen to 11.6 %, and that youth unemploy-

ment rate is “remaining 3.7 higher than the adult rate”,

2

thus remaining one of the

highest. In that context women experience similar difficulties, access to employ-

ment is more difficult.

This situation is worsened by strong religious and cultural barriers which prevent

women to enter the labour market. As a matter of fact, female participation rate to

the labour market remains extremely low; for the whole region, it is estimated to be

of about 21.7 %, one of the lowest rate observed in the whole world. Complying

with written and unwritten rules, women remain “invisible” on the labour market.

Yet, as the number of graduated women increases, some improvements can be

observed over the past years. This is demonstrated by Tunisia. Despite a complex

environment, women labour force participation rate on the labour market has

gained almost 10 points in the last decade (from 25 % in 2005 to 34 % in 2012),

while that of all women access is of 26 %. A similar demonstration can be

developed for Algeria where the important increase of graduated women is an

element that has contributed to improve their labour force participation rate which

has grown from 6.6 % in 2000 to 16.6 % in 2013 (see Fig. 7.1).

When the detailed data is available, it appears that tertiary graduated women

ability to enter the labour market is much higher. For instance, while all women

1

For purpose of analysis consistent with part I, countries included in the geographic analysis are

Algeria, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Tunisia and the United Arab

Emirates.

2

Source: ILO (2015a).

© Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2017

C. Schmuck, Women in STEM Disciplines, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-41658-8_7

157

labour force participation rate is of 65 %, in Tunisia, it reaches 78 % for women

holding the equivalent of a master and almost 88 % for those who have a PhD. In

Qatar, 61 % of tertiary graduated women enter the labour market (which is 10 %

higher than what is observed for all women). In Saudi Arabia where all women

labour force participation rate is much closer to the regional average with 20 %,

about 80 % of tertiary graduated women enter the labour market.

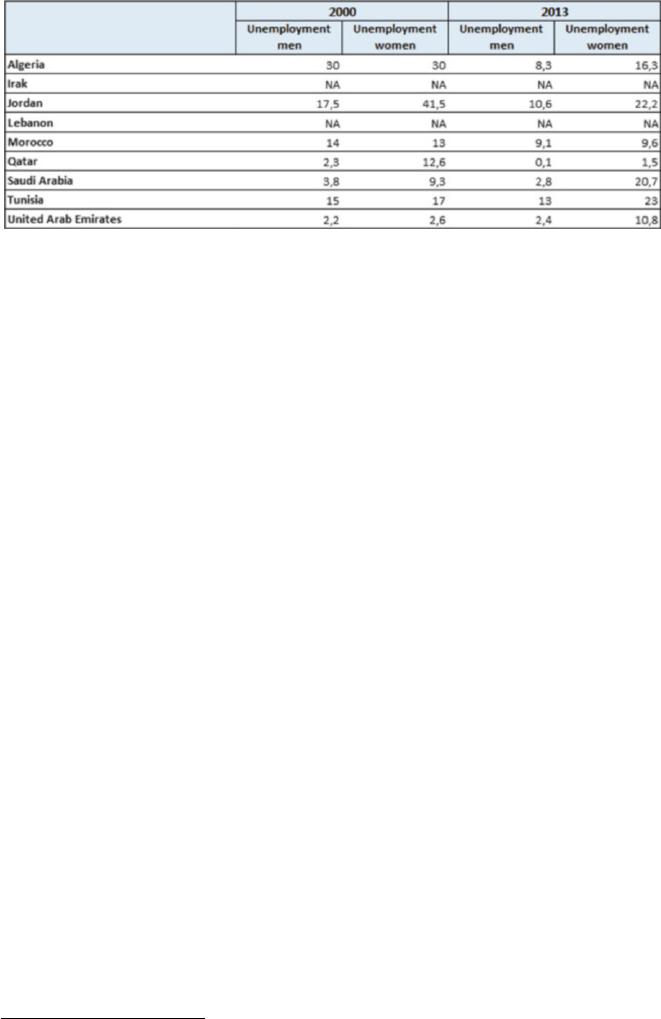

However while access to the labour market has improved in most countries

where the proportion of tertiary graduates has increased, access to employment

hasn’t, except in a few countries. Overall unemployment levels reflect a wider

problem of these economies, which despite continued growth until 2008 have not

created enough jobs for new entrants. As dem onstrated by the World Bank in a 2013

report, employment grew but not as rapidly as the working age population; as a

result both MENA countries are experiencing a “youth bulge”.

3

In countries that benefit from a strong commitment from public decision makers,

women have gained better access to employment. For instance, in Jordan, women

level of unemployment has been cut by half, from 41.5 % in 2000 to 22.2 % in 2013

(see Fig. 7.2). In addition the gender gap with men has decreased importantly from

24 % to 11 %. In Qatar the same situation is observed; women access to work has

also significantly improved since their level of unemployment has dropped from

12.6 % to 1.5 %. In Morocco, according to the data available, the level of unem-

ployment of men and women was already equivalent in 2000; for both gender it has

diminished in similar proportion to reach approximately 9 %.

To the contrary women situation has deteriora ted in Algeria, Saudi Arabia and

the United Arab Emirates in the last decade either in terms of unemployment level

NA

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

Algeria Irak Jordan Lebanon Morocco Qatar Saudi

Arabia

Tunisia United

Arab

Emirates

LFMmen LFM women

Fig. 7.1 Labour force participation rate by gender and country in 2013. Source: Analysis of

total labour force participation rate by gender 2013 or nearest year available, ILO, extraction

August 2015

3

Source: World Bank (2013).

158 7 Catching Up on Studies Not Employment

(from 9.3 to 20 % in Saudi Arabia and 2.4 to 10.8 % in the United Arab Emirates) or

gender gap (no gender gap in Algeria in 2000, gender gap of 8 % in 2013). However

holding a degree doesn’t always bring an advantage to women. For instance, in

Saudi Arabia tertiary graduated women face an unemployment rate which is higher

than that of all women: 20.7 % versus 9.3 %. Even being graduated in STEM

doesn’t appear to improve employment level either. In fact results to the online sur-

vey

4

indicate that women from MENA who are tertiary graduated in STEM

experience an unemployment level which is higher than that of all tertiary graduate

respondents: 18 % versus 16 %. This reflects the fact that qualified women face

much higher barrier to acce ss emp loyment than men. Not only do they have to

overcome religious and cultural barriers, they also have to face legal and institu-

tional obstacles which makes it more costly for companies to hire them and forbid

them to work in certain types of jobs considered to be “against women morals”.

5

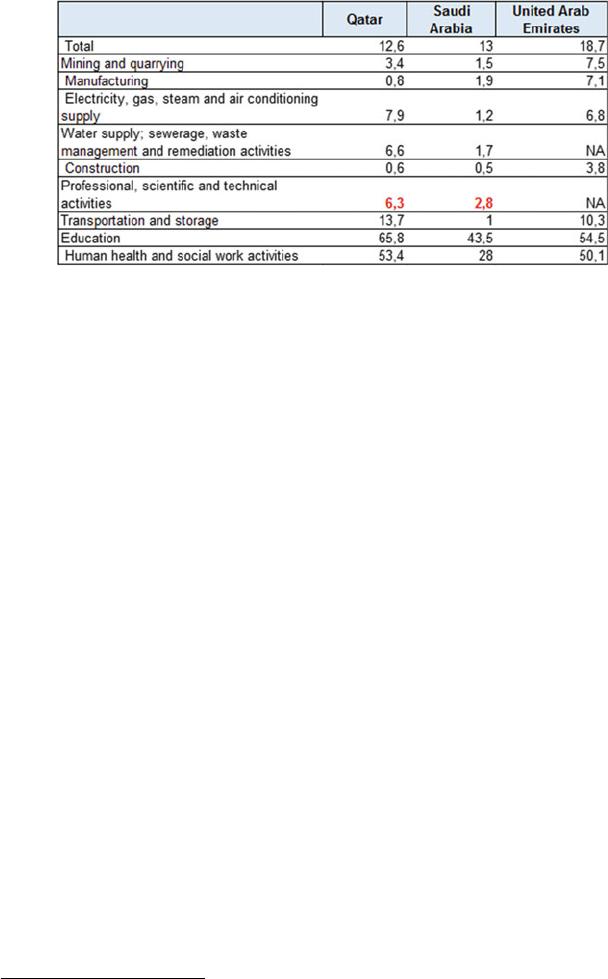

7.1.2 Sectors and Occupation

Despite all these obstacles, are there some countries where the proportion of women

in scientific or technical jobs reflects the strong increase of STEM graduated

women? On this subject the lack of data doesn’t allow to develop a thorough

analysis. However some preliminary conclusions can be developed based on what

is available. In all of the countries observed in this report, the proportion of women

in technical and professional jobs is well below 50 % (see Fig. 7.3). Yet there are

some countries where the situation is slightly more positive. In Algeria and Tunisia,

for instance, the higher proportion of graduated women in STEM is reflected by the

higher proportion of women in technical occupations. But that doesn’ t apply to

Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates which are also countries where

Fig. 7.2 Unemployment rate by gender. Source: Analysis of tertiary graduated unemployment

rate by gender, ILO, extraction: August 2015

4

Source: Yfactor 2014 survey, 196 respondents from 20 MENA countries.

5

Source: World Bank (2013).

7.1 Middle East and North Africa 159

the proportion of graduated women in STEM is high, but do not have high

proportion of women in these jobs.

A closer look at the feminization of scientific and technical sectors confirms the

fact that the proportion of women in these jobs remains low. More specifically on

professional, scientific and technical activities, they represent less than 10 % of

workers. The only sectors in which the proportion of women is higher are human

health and social work activities, as well as education (see Fig. 7.4).

Clearly choosing to study STEM does not bring women from the MENA regions

the type of jobs their studies are preparing them for. In fact, there is an increasing

gap between the number of women who are graduated and access to qualified jobs.

This gap has been widened by the general lack of employment opportunities from

the private sector.

However the high proportion of women who are gradu ated in computing

(MENA countries rank second, after East Asia by the proportion of graduated

women in ICT which reached 47.4 % in 2013) and therefore can more easily

work at a distance does open new possibilities to practise remote working. It is an

option that is probably curr ently generating results that can ’t be measured. It is

known that current statistics do not reflect the rece nt growth of the “invisible

economy”, which is viewed by some obser vers as a “powerful socio-economic

phenomenon

6

” led by women, as it enables them to generate revenue from home.

The need for a programme on gender and economic inclusion is strong. This has

been highlighted both by the World Bank and the World Economic Forum. Hope-

fully results from pilot experiment such as the one developed in Jordan focused on

facilitating school-to-work transition by supporting young women to acquire “on-

the-job experience and skills”

7

will enable to identify solutions. In addition new

32.7

33.7

48.7

15.5

31.7

45.4

21

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

Algeria Jordan Lebanon Qatar Saudi

Arabia

Tunisia United Arab

emirates

Fig. 7.3 Feminization of technical occupations. Source: Analysis of unemployment by occu-

pation by gender, nomenclature: ISCO 88 for Algeria, Jordan, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, the United

Arab Emirates, extraction: August 2015

6

Source: “Gulf women, competing economies”, Dr Amal Mohammed Al-Malki, World Bank,

March 6, 2015.

7

Source: World Bank (2010).

160 7 Catching Up on Studies Not Employment

initiatives are conducted to make this change. For instance, the 2014 initiative of the

World Economic Forum on “rethinking Arab employment” held by the Gulf

Cooperation Council

8

reflects the level of awareness of public and private decision

makers on that subject, as does the more recent initiative from the United Nations

Industrial Development Organization which is working on the project of “promot-

ing women empowerment for inclusive and sustainable industrial development in

the MENA region”.

7.2 South-West Asia

9

7.2.1 Employability

Both in Bangladesh and Iran, women labour force participation rate hasn ’t

improved over the past years (see Fig. 7.5). As in the Middle East and North Africa,

women access to the employment market is among the lowest in the world. No

detailed data is available on the situation of graduated women, but the overall

evolution indicates that the increas e of graduated women is not reflec ted by an

improvement of women access to the employment market. In all these countries,

which are also among those where women face the most important level of

discrimination according to SIGI (Social Institutions and Gender Index), access

to the employment market has decreased for graduated women in the past 10 years.

Fig. 7.4 Feminization of sectors. Source: Analysis of employment by economic activity by

gender, ISIC Rev.4 (except for UAE), ILO, extraction: August 2015

8

Gulf Cooperation Council members: Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United

Arab Emirates.

9

For purpose of analysis consistent with part I, countries included in the geographic analysis are

Bangladesh and Iran.

7.2 South-West Asia 161

Both Bangladesh and Iraq have experienced substantial growth over the past

years, but it has been a jobless growth; unemployment remains high both for men

and women (see Fig. 7.6). Even in Bangladesh where unemployment is much

lower, this results from strong increase of vulnerable forms of employment (mostly

subsistence agriculture), which accounts for three quarter of all employment.

7.2.2 Sectors and Occupation

As in MENA and sub-Saharan African countries, the proportion of women working

in technical occupations is below 50 % (see Fig. 7.7). Yet the growing number of

graduated women in STEM is reflected by their growing share in technical jobs .

In the two countries, the share of women holding a degree in STEM has

increased importantly over the past 10 years; in Bangladesh it has grown to 17 %

of EMC resulting from an increase of 57 %. During the same period of time, it has

grown in similar proportion in Iran (þ56 %); as a result women represent 21 % of

EMC graduates. This could provide an element of explanation to the increasing

proportion of women in sectors such as manufacturing and construction in

Bangladesh. In manufacturing it moves from 25 to 28 %, in construction from

7 to 9 % (see Fig. 7.8).

Conversely the proportion of women working in manufacturing in Iran decreases

from 29 % to 23 % and remains about similar in construc tion. In Iran a strong

Fig. 7.5 Labour force participation rate by gender and country in 2000 and 2013. Source:

Analysis of total labour force participation rate by gender 2000 and 2013 or nearest year available,

ILO, extraction: August 2015

Fig. 7.6 Unemployment rate by gender in 2003 and 2013. Source: Analysis of tertiary graduate

unemployment rate by gender, ILO, extraction: August 2015

162 7 Catching Up on Studies Not Employment

increase in the proportion of graduated women in manufacturing had been

observed, which is not reflected at all by their percentage in that sector.

7.2.3 Remuneration

No data is available for any of the two countries on this subject.

0

5

10

15

20

25

Bangladesh Iran

2005 2013

Fig. 7.7 Feminization of technical occupations in 2005 and 2013. Source: Analysis of employ-

ment by occupation by gender, nomenclature in 2005 and 2013 (or nearest years available),

ISCO 88, extraction: August 2015

Fig. 7.8 Feminization of sectors. Source: Analysis of employment by economic activity by

gender 2013 or nearest year available, ISIC Rev.4 ILO, ISIC Rev.3, extraction: August 2015

7.2 South-West Asia 163

7.3 Sub-Saharan Africa

10

7.3.1 Employability

Over the past years, women labour force participation rate has improved in the

region. ILO estimates that the whole region has the highest labour force participa-

tion rate of all regions with a regional average of 70.9 %, which is high above the

global average at 63.5 %,

11

and a gender gap which is well below 20 % in most

countries observed. Yet in less-de veloped countries rather than being a sign of

empowerment, this reflects the absolute necessity to work for a living. In addition,

the situation differs important ly from one country to the other; as illustrated by

Lesotho, Madagascar, Rwanda or Zimbabwe where on the contrary women labour

force participation rate is declining. As confirmed by SIGI (Social Institutions and

Gender Index), these are all countries where the level of discrimination against

women is among the highest, which is an additional element that prevents women

from entering the labour market (see Fig. 7.9).

Levels of unemployment contrast widel y from one country to another yet tend to

be fairly similar between men and women (see Fig. 7.10). The gender gap appears

to be low, in general well below 5 %. Rather than being a positive indicator, this is

the result of the fact that a majority of women are working in vulnerable jobs. The

share of women who are either own-account workers or cont ributing family

workers is one of the highest in the world. It is estimated to reach 76.6 % for the

whole region, which is 30 % higher than the world average (54.3 %). A closer look

at the count ries observed in this report confirms that the proportion of women

working for “households as employers” is indeed extremely high, reaching more

than 86 % in Ethiopia and Zimbabwe.

Fig. 7.9 Labour force participation rate by gender and country in 2000 and 2013. Source:

Analysis of tertiary graduates labour force participation rate by gender 2000 and 2013 or nearest

year available, ILO, extraction: August 2015

10

For purpose of analysis consistent with part I, countries included in the geographic analysis are

Ethiopia, Lesotho, Madagascar, Rwanda, South Africa and Zimbabwe.

11

Source: ILO (2015b).

164 7 Catching Up on Studies Not Employment

In this context rather than providing a better access to employment, being

graduated should enable access to better jobs. The lack of data on graduated

women unemployment level doesn’t allow to check if that applies to women.

7.3.2 Sectors and Occupation

The proportion of women working in technical occupations is below 50 % in mos t

countries, reflecting the low proportion of graduated women in STEM (see

Fig. 7.11). In the two countries where women represent more than 50 % of the

workforce, this is consistent with the recent evolution of the proportion of

graduated women in STEM (30 % in EMC for Lesotho, 50 % in science for

South Africa).

NA

32.9

63.2

42.6

37.5

55.4

32.3

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

Ethiopia Lesotho Madagascar Rwanda South Africa Zimbabwe

2005 2013

Fig. 7.11 Feminization of technical occupations in 2005 and 2013. Source: Analysis of

employment by occupation by gender, nomenclature in 2005 and 2013 (or nearest years available),

ISCO 88, data not available for Lesotho, extraction: August 2015

Fig. 7.10 Unemployment rate by gender in 2003 and 2013. Source: Analysis of total unem-

ployment rate by gender and educational attainment, ILO, extraction: August 2015

7.3 Sub-Saharan Africa 165

Similarly the proportion of women in professional, scientific and technical

activities is below 45 % in all count ries (see Fig. 7.12). But South Africa stands

out as one of the countries where the proportion of women in sectors such as energy,

construction and information and communication is among the highest.

Fig. 7.12 Feminization of sectors. Source: Analysis of employment by economic activity by

gender 2013 or nearest year available, ISIC Rev.4 ILO, except Lesotho ISIC Rev.3 extraction:

August 2015

Economic activity Ethiopia Madagascar

South Africa

Total -46% -35%

-26%

Agriculture, forestry and fishing -31% -36%

-33%

Mining and quarrying -89% -74%

-2%

Manufacturing -50% -19%

-71%

Electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply -3% 16%

4%

Water supply; sewerage, waste management and

remediation activities -36% 39%

NA

Construction -65% -10%

-37%

Wholesale and retail trade; repair of motor vehicles and

motorcycles -41% -5%

-10%

Transportation and storage -17% 60%

24%

Accommodation and food service activities -61% -32%

NA

Information and communication -39% -36%

NA

Financial and insurance activities -33% -12%

-16%

Real estate activities -23% 48%

NA

Professional, scientific and technical activities -26% -20%

NA

Administrative and support service activities -41% 49%

NA

Public administration and defence; compulsory social

security -28% -20%

NA

Education -24% -12%

-33%

Human health and social work activities -60% -36%

NA

Fig. 7.13 Remuneration gender gap by sectors in 2013. Source: Analysis of mean nominal

monthly earnings by gender and sector ISIC Rev.4 2013 or nearest year available, no data

available for, data for Kenya ISIC Rev.2, ILO, extraction: August 2015

166 7 Catching Up on Studies Not Employment