Talk softly but carry a big stick: transfer pricing

penalties and the market valuation of Japanese

multinationals in the United States

Lorraine Eden

1

, Luis F Juarez

Valdez

2

and Dan Li

1

1

Department of Management, Texas A&M

University, College Station, TX, USA;

2

Department of Accounting and Finance,

Universidad de las Americas-Puebla, Cholula,

Mexico

Correspondence:

Professor L Eden, Department of

Management, Texas A&M University,

4221 TAMU, College Station,

TX 77843-4221, USA.

Tel: þ 1 979 862 4053;

Fax: þ 1 979 845 9641;

E-mail: [email protected]

Received: 12 February 2004

Revised: 1 September 2004

Accepted: 4 October 2004

Online publication date: 19 May 2005

Abstract

Corporate income tax law in OECD countries requires multinational enterprises

(MNEs) to set their transfer prices according to the arm’s length standard. In

1990 the United States (US) government introduced a transfer pricing penalty

for cases where MNEs deviated substantially from this standard. More than two

dozen other governments have followed suit. Our paper uses event study

methodology to assess the impact of the US transfer pricing penalty on the

stock market valuation of Japanese MNEs with US subsidiaries in the 1990s. We

find that the penalty caused a drop in their cumulative market value of $56.1

billion, representing 12.6% of their 1997 market value.

Journal of International Business Studies (2005) 36, 398–414.

doi:10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400141

Keywords: transfer pricing; tax penalty; event study; market value; ADR; Japanese

multinationals; IRS

Introduction

Nobody wants to pay taxes. No wonder, then, that so many companies spend so

much effort trying to avoid them. Almost every big corporate scandal of recent

years, from Enron to Parmalat, has involved tax-dodging in one form or

another. (The Economist, 2004, 71)

Corporate income tax law in all OECD countries requires multi-

national enterprises (MNEs) to set their transfer prices according to

the arm’s length standard; that is, the external market or arm’s

length price that two unrelated firms would set for the same or

similar product traded under the same or similar circumstances, as

the product traded within the MNE (Eden, 1998, 2001). In 1990,

the United States (US) government introduced a transfer pricing

penalty – Internal Revenue Code y6662 – for cases where MNEs

engage in transfer price manipulation (TPM), setting a transfer

price that deviates significantly from the arm’s length price. The US

Congress approved the y6662 penalty partly in response to the

widespread perception that foreign-owned, particularly Japanese,

MNEs were paying little US tax (Inoue, 1990).

When first introduced, the penalty was broadly condemned by

other OECD tax authorities, but over the past few years the policy

has begun to spread. Ernst & Young (2004), for example, document

the international tax policies of 46 countries in 2003; 27 of the

Journal of International Business Studies (2005) 36, 398–414

&

2005 Academy of International Business All rights reserved 0047-2506 $30.00

www.jibs.net

countries now have explicit transfer pricing penalty

legislation modeled on the US legislation.

How important an issue is transfer pricing? In

Ernst & Young’s (2003, 7) most recent global

transfer pricing survey, 86% of MNE parent and

93% of subsidiary respondents stated that transfer

pricing was the most important international tax

issue they currently face. The respondents noted

that almost half their MNEs had been audited since

1999, and two-thirds expected to be audited within

the next 2 years (Ernst & Young, 2003, 10). Of the

MNEs that had been audited, one-third of the

audits concluded with an adjustment (that is, the

MNE owed more tax to the national tax authority).

Tax penalties were threatened in one-third of these

cases and actually imposed in one-sixth of them

(Ernst & Young, 2003, 7). To quote Ernst & Young

(2003, 15): ‘If an MNE is subject to an adjustment as

the result of a transfer pricing examination, there is

almost a one-in-three chance of being threatened

with a penalty, and a one-in-seven chance of

actually having one imposed.’

Global dollar estimates for TPM are hard to come

by. The US Department of the Treasury (1999, 3)

estimated the annual loss in US income tax revenue

due to TPM at $2.8 billion. Manufacturing

accounted for one-half the estimated tax loss,

followed by wholesale and retail trade; over half

the estimated loss came, not surprisingly, from

large corporations (US Department of the Treasury,

1999, 13). In terms of actual, not estimated, tax

dollars, in fiscal year 2002, the US Internal Revenue

Service (IRS) recommended $5.56 billion in transfer

pricing adjustments (that is, additional income tax

owed by the MNEs) and spent $15 million on direct

examination costs (US Department of the Treasury,

2003, 10). Estimates of the impacts of the transfer

pricing penalty are not available, but a recent IRS

survey revealed that 31% of US MNEs were spend-

ing between $100,000 and $1 million dollars

annually preparing the contemporaneous transfer

pricing documentation required as a precondition

to avoid being hit by the y6662 penalty (US

Department of the Treasury, 2003). Moreover, even

the threat of transfer pricing adjustments and

penalties can affect a multinational’s market valua-

tion. Swatch, for example, saw its stock price drop

by 11% on the Zurich stock exchange when two

employees claimed to the US Labor Department

that the Swiss MNE had used transfer price

manipulation through its British Virgin Islands

subsidiary to evade millions of dollars in taxes

(Lopez, 2004).

These numbers suggest that both the threat and

the reality of transfer pricing penalties should

affect the strategies and market valuation of

MNEs. The purpose of our paper is to address

exactly that question: How do transfer pricing

penalties affect the behavior and profits of multi-

nationals? We develop a theoretical model analyz-

ing the penalty’s impact on MNE after-tax profits.

We hypothesize that MNEs that engage in TPM

should respond to the transfer pricing penalty

either by continuing their existing pricing policies

(and therefore risking being hit with the penalty),

or by setting government-approved arm’s length

prices (and therefore paying more income taxes).

We outline the circumstances under which MNEs

would choose one or the other of these alternatives.

In either case, the MNE’s cash flows should fall,

having a negative impact on the firm’s stock market

valuation.

We test our model using an event study of the

stock market prices of American Depository

Receipts (ADRs) of all Japanese multinationals with

US subsidiaries over the 1990s. A brief history of the

US transfer pricing penalty legislative process from

1989 to the present is used to isolate the critical

dates for our event study. We follow the rigorous

research methodology design for event studies laid

out in MacKinlay (1997), McWilliams and Siegel

(1997) and McWilliams et al. (1999).

Our results show a strong negative reaction to the

penalty for Japanese stock market returns in the US,

providing support for our theoretical model, even

though there has been only one major penalty case

to date. We estimate the impact of the y6662

legislation on the market value of the Japanese

ADRs between 1990 and 1997 to be a cumulative

loss of $56.1 billion (an average $7 billion dollars

per year), which is 12.6% of the ADRs’ market value

at the end of the period. This drop in market value

can be compared with US Treasury estimates,

mentioned above, of $2.8 billion in annual forgone

tax revenues due to TPM and $5.56 billion in

recommended tax adjustments in 2002. Thus, the

market value impact – on Japanese MNEs alone –

appears to be larger than the US Treasury’s esti-

mates of forgone tax revenues.

We therefore conclude that the transfer pricing

penalty – and even the threat of the penalty – can

be punitive for targeted firms. The penalty dis-

courages transfer price manipulation and reduces

the MNEs’ market value. Talking softly but carrying

a big stick does encourage tax compliance, albeit at

a very high cost in terms of lost market value.

Talk softly but carry a big stick Lorraine Eden et al

399

Journal of International Business Studies

Literature review

Economic theory suggests that MNEs will maximize

global after-tax profits by shifting revenues to low-

tax, and deductions to high-tax, jurisdictions

(Horst, 1971). Manipulation of transfer prices is

widely believed to be the primary route for such

income shifting. There has been a large theoretical

literature on transfer pricing responses to income

tax differentials (Horst, 1971; Halperin and Srinid-

hi, 1987; Eden, 1998). Empirical studies by Grubert

et al. (1993), Harris (1993), Harris et al. (1993),

Klassen et al. (1993), Jacob (1996), Clausing (1998)

and Collins et al. (1998), among others, suggest that

high tax rates negatively affect volume and location

of foreign direct investment (FDI), and encourage

aggressive transfer pricing techniques. Hines (1999,

318) concludes that international tax avoidance is a

‘successful activity’, limited only by ‘available

opportunities and the enforcement activities of

governments’.

Most of the empirical work on this topic has been

macroeconomic in nature, using US foreign direct

investment data. An alternative approach is to

analyze the impact of tax policy changes on stock

market prices, using event study methodology.

Schipper et al. (1987), Cornett and Tehranian

(1990), Malatesta and Thompson (1993), Barth

et al. (1995) and Harper and Huth (1997), for

example, measure the impacts of government tax

and regulatory changes on firms’ abnormal returns.

As policy changes typically provide many possible

event dates, it is critical to select those dates that (i)

provide major new information and (ii) are unanti-

cipated by the markets.

Three recent surveys of event study research

(MacKinlay, 1997; McWilliams and Siegel, 1997;

McWilliams et al., 1999) argue that past researchers

often paid inadequate attention to theory and

research design issues, leading to spurious, overly

optimistic results. The authors outline the

necessary components of a ‘good’ event study

design. In our paper, we follow the steps outlined

by these authors, using event study methodology to

provide an ‘inverse test’ of transfer price manipula-

tion.

If foreign MNEs did manipulate transfer prices in

order to artificially shift profits out of the US, then

introduction of the penalty should reduce their

incentive to manipulate transfer prices, causing a

drop in cash flows and generating negative cumu-

lative average returns (CARs). We therefore expect

the market valuation of foreign MNEs with US

subsidiaries to fall in response to the introduction

of penalty legislation, and to fall furthest for

those MNEs using aggressive transfer pricing tech-

niques.

Theory development

We hypothesize that a transfer pricing penalty has

two key effects: a direct effect and an indirect effect.

The first effect is the penalty itself, which is an

extra, nondeductible tax levied as some percentage

a of the MNE’s profits. The penalty is not auto-

matic, but depends on the extent of TPM as defined

by the tax authority: that is, by the gap between the

MNE’s transfer price p and the tax authority’s arm’s

length transfer price W

ˆ

, multiplied by the volume

of intrafirm trade X. The regulated transfer price, in

practice, is not a single price but an arm’s length

range; however, in the interests of simplicity, we

assume W

ˆ

is a fixed price.

The penalty is levied on top of the corporate

income tax rate t on the MNE’s profits. There is

some probability U of a penalty being levied: the

larger the extent of TPM, the more likely the

assessment of a penalty. For simplicity, assume the

penalty is triggered by a transfer pricing gap that

exceeds some known percentage k of the arm’s

length price W

ˆ

. The transfer pricing penalty T is

therefore

T ¼ Fatðp

^

WÞX ð1Þ

which is positive if U40 and (pW

ˆ

)XkW

ˆ

, and zero

if U¼0orif(pW

ˆ

) okW

ˆ

. Equation (1) suggests that

the penalty will be larger, the higher the probability

of assessment U, the higher the penalty tax rate a

and corporate income tax rate t, the greater the

degree of transfer price manipulation (pW

ˆ

), and

the larger the volume of intrafirm trade X.

Second, if a penalty is assessed, the tax authority

replaces the MNE’s transfer price p with the arm’s

length price W

ˆ

and restates the MNE’s profits with

the new transfer price.

1

The indirect effect of the

penalty is the reassessment of income tax based on

substituting the arm’s length price W

ˆ

for the MNE’s

transfer price p. The indirect effect also depends

positively upon U, t and X.

Where the MNE’s chosen transfer price p differs

from the regulated price W

ˆ

, the MNE pays an

additional tax if the tax authority audits the MNE

and finds that the transfer pricing differential

exceeds the minimum allowable gap. By staying

inside the arm’s length range set by the tax

authority, the MNE avoids the penalty but reduces

its profits from manipulating the transfer price.

Talk softly but carry a big stick Lorraine Eden et al

400

Journal of International Business Studies

Thus, the penalty reduces the MNE’s marginal after-

tax profitability. Our first hypothesis therefore is:

H1: The transfer pricing penalty reduces the net

profitability of the MNE.

In the absence of the penalty, the MNE would

simply overinvoice its transfer price whenever the

US corporate income tax rate was higher than

the foreign tax rate. With the penalty, however, the

incentive to manipulate the transfer price is

reduced for two reasons. First, as U rises, the MNE

is less willing to take chances with its transfer

pricing policy. Second, the higher the penalty

rate a the less likely the MNE is to overinvoice

because the cost of the penalty rises. In effect, the

MNE balances the tax-saving gains from transfer

price manipulation against the probability and

size of the penalty. The penalty provides an

additional constraint on the MNE’s transfer

pricing range, reducing its overall net profitability

from transfer price manipulation. Our second

hypothesis is:

H2: The higher the probability of penalty assess-

ment and/or the higher the penalty rate, the less

likely is the MNE to engage in transfer price

manipulation.

There is a third effect to the transfer pricing

penalty. Most tax authorities also require the MNE

to contemporaneously collect transfer pricing

documents, in both primary and secondary forms,

and to make these available to the tax authority on

request. Contemporaneous documentation is a

necessary, but not sufficient, condition to avoid

the penalty. Therefore, there are administrative

costs attached to the penalty regulations, which

should be included in a full model.

2

Let C

D

represent the administrative costs of complying

with the penalty regulations, and assume C

D

is

negatively related to the probability of the

penalty. The MNE’s optimal transfer price is now

affected because documentation reduces the

probability of the penalty being levied, all other

things being equal, and thus permits a higher

transfer price: that is, documentation reduces

the likely penalty costs and encourages greater

transfer price manipulation. This suggests our third

hypothesis:

H3: Because contemporaneous documentation

reduces the probability of a tax penalty, it has the

unintended consequence of encouraging transfer

price manipulation.

A brief history of the y6662 transfer pricing

penalty

Tax penalties have been part of the US income tax

code for many years, but they were aimed at severe

cases of tax evasion, and were seldom levied.

Congress, cognizant of the IRS’s apparent reluc-

tance to levy tax penalties, consolidated all the

different penalties on 19 December 1989 into

y6662. In 1990 the US government introduced

added an accuracy-related penalty for cases where

the MNE’s transfer prices deviated significantly

from IRS-approved arm’s length transfer price.

3

The transfer pricing penalty was introduced for

two reasons. The first rationale was IRS experience

in transfer pricing audits (Lowell et al., 1994, 352).

The Service had found that most taxpayers had no

documentation, and were unable to explain their

transfer prices at the time of an audit, causing

increased time and costs for the Service. The IRS

believed that taxpayer compliance would improve

if an inaccuracy penalty were introduced.

4

A second reason was the widespread perception

that foreign MNEs were underpaying their US taxes.

The Wall Street Journal (Wall Street Journal,

20

February 1990) interviewed an IRS official who

noted that, while inward FDI and sales revenues

had surged in the 1980s, US tax payments by

foreign-owned subsidiaries had not grown (Stout,

1990). (Underlined events are considered signifi-

cant and tested in the event study below.) He also

noted that more than 36,000 foreign-owned com-

panies filing US tax returns reported negative

taxable income, and that the IRS was stepping up

its surveillance of foreign-owned MNEs. This was

documented on

10 July 1990, when the US Ways

and Means Committee conducted hearings (known

as the Pickle hearings after its chair) into tax

compliance by foreign subsidiaries in the US. An

IRS report, based on an investigation of 36 large

foreign-owned subsidiaries, concluded that most

had paid little or no US taxes over a 10-year period

(Heck, 1990; Inoue, 1990). About half the subsidi-

aries had Japanese parents. The study concluded

that inflated transfer prices for goods purchased

from foreign parents and the performance of

functions not fully charged to foreign parents were

the main causes for the low US taxes. A former US

Treasury official was quoted as saying, ‘For most

Japanese firms operating in the US, it’s a question of

when, not if, they’ll be audited and investigated by

the IRS’ (Inoue, 1990).

These events provided support for congressional

critics who contended that foreign firms were

Talk softly but carry a big stick Lorraine Eden et al

401

Journal of International Business Studies

manipulating their books to avoid paying US tax.

As a result, Congress developed legislation for a

new transfer pricing penalty (Schmedel, 1990). On

5 November 1990, as part of the Revenue Reconci-

liation Act, y6662(e) was added to the Income Tax

Code, creating a penalty for transfer pricing mis-

valuations. The 1990 legislation differentiated

between a substantial valuation misstatement

(SVM) and a gross valuation misstatement (GVM).

With a US federal tax rate of 34%, the penalty raised

the effective US tax rate to 41% for an SVM

(1.2 34) or 48% for a GVM (1.4 34). An escape

clause from the penalty was provided in y6664(c),

requiring the taxpayer to show that there was

reasonable cause for the underpayment and that

the taxpayer had acted in good faith with respect to

the transfer price. As part of RRA ‘90, Congress

directed the IRS to develop regulations to imple-

ment the y6662 legislation.

The IRS issued its first tax penalty regulations,

covering everything but the transfer pricing penalty

on

4 March 1991, with essentially unchanged final

regulations issued on 30 December 1991. However,

it took the IRS until

13 January 1993 to prepare

and release its proposed transfer pricing penalty

regulations for y6662(e).

5

Issued along with the

revised y482 temporary transfer pricing regulations,

the penalty caused immediate controversy among

US and foreign transfer pricing professionals. The

most controversial issue was the ‘reasonable cause

and good faith’ exemption in y 6664(c). To qualify

for the exemption, the taxpayer had to meet two

tests: (i) contemporaneously document the transfer

pricing methodology by the time taxes were filed,

and provide the documentation to the IRS within

30 days of a request; and (ii) prove that the transfer

pricing result, more likely than not, would be

sustained on its merits in a transfer pricing audit.

6

On 2 February 1994, the IRS issued temporary

y6662 regulations to take into account the changes

introduced by RRA ‘93. The changes tightened the

rules, introducing two classifications of documents

(principal and background) required for contem-

poraneous documentation, and requiring the tax-

payer to use a transfer pricing methodology that

met the best method test of y482. On

17 March

1994, the temporary regulations were amended to

raise the disclosure standard from ‘not frivolous’ to

‘reasonable basis’, as required in RRA ‘93. On

8 July

1994 the y6662 regulations were updated to con-

form to the IRS final y482 regulations. The key

change was to provide a complete list of all the

principal and supporting documents required for

contemporaneous documentation. This was the last

major change in the y6662 regulations.

7

The IRS

formalized the penalty process by establishing a

penalty oversight committee to ensure uniform

application of y6662, on

11 March 1996.

The first y6662 non-transfer pricing penalty

(company unnamed) under the pre-1994 rules was

announced by the IRS at a conference on 8 June

1996. The first transfer pricing penalty was

announced on

17 September 1997. The one, major

transfer pricing penalty case to date has been DHL,

8

filed on 30 December 1998, where the US Tax

Court levied a 40% penalty for the undervaluation

of DHL’s sale of its trademark to a foreign related

corporation, and a 20% penalty for failing to charge

for the use of its trademark in earlier years. The

total amount of y 6662 penalties was $162.5 mil-

lion.

9

Thus, nine years elapsed between December

1989, when Congress first consolidated the tax

penalties into y6662, and December 1998 when the

first significant transfer pricing penalty was upheld

in Tax Court. Since that time there have been no

publicly discussed, major transfer pricing penalties

announced by the IRS. Our historical analysis

therefore stops with the DHL case.

Data and methods

As our historical review shows, Japanese MNEs were

perceived by the IRS and US Congress to be the

most serious tax underpayers in the 1990s.

10

Japanese firms were targeted in the Pickle hearings

in 1990. Hufbauer and van Rooij (1992, 116–117)

calculated that the 1990 net return on sales in the

US was 3.4% for US MNEs, but only 0.1% for

Japanese MNEs. Eden (1998, 373) reported an

operating profit to gross income ratio of 7.1% for

US majority-owned foreign affiliates in Japan

compared with 0.2% for Japanese affiliates in

the US. In the early 1990s, the IRS launched several

transfer pricing cases against Japanese MNEs in the

US, including Epson, Fujitsu, Hitachi, NEC, Nissan,

and Yamaha (Borkowski, 1997, 31). Therefore, we

expect that, even though the transfer pricing

penalty should have negatively affected all foreign

MNEs with cross-border intrafirm trade, the penalty

should have most strongly and negatively affected

the stock market prices of Japanese MNEs with US

affiliates because the y6662 legislation was targeted

primarily at these MNEs.

Japanese MNEs with US affiliates over the 1990s

are therefore selected as the appropriate sample for

testing our hypotheses. We collected data on the

ADRs of all the Japanese MNEs with US affiliates

Talk softly but carry a big stick Lorraine Eden et al

402

Journal of International Business Studies

over this period. The ADRs must have been listed

on the NYSE and NASDAQ stock markets for a

minimum of 255 days between 1989 and 1999. In

all, 24 Japanese MNEs met these criteria and were

included in our study. They are listed in Table 1.

Using Eventus version 6.2 and CRSP data, we

employ event study methodology to test whether

y6662 negatively affected the stock market returns

of foreign MNEs with US subsidiaries, using the 10

underlined dates in our history section. We care-

fully checked our event windows and did not find

evidence of confounding events.

11

As outlined in McWilliams and Siegel (1997, 628),

we compute the standardized abnormal returns,

where the abnormal return is standardized by its

standard deviation.

12

The standardized returns are

then cumulated over 2-day (1, 0) and 3-day (1,

þ 1) event windows

13

to derive measures of the

cumulative abnormal return (CAR), as a percentage,

for each firm.

14

Assuming markets are efficient, the

event contains significant information that is

unanticipated, and there are no confounding

events, the test statistic Z provides a good test of

whether the CARs are statistically significant.

15

Another important issue raised by McWilliams

and Siegel (1997, 635–636) is the presence of

outliers, which are important in small samples

typical of event studies. We compute two non-

parametric tests to test for outliers: the ratio of

positive to negative returns (PRNEG), and the

binomial Z statistic, which tests whether PRNEG

is statistically significant (McWilliams and Siegel,

1997, 634–635).

The next stage of our research design, following

McWilliams and Siegel (1997), tests our hypotheses

about the time-series and cross-sectional variation

in abnormal returns using three post hoc analyses,

two tests using multiple regression techniques and

a third looking at the impact of the penalty on the

Tokyo stock market. We employ additional regres-

sion diagnostics and bootstrapping methods as

further tests for small sample bias and outliers. In

the last stage of the research design, we conclude by

estimating the cumulative wealth impact of the

transfer pricing penalty, as discussed in McWilliams

et al. (1999).

Empirical results

Event study results

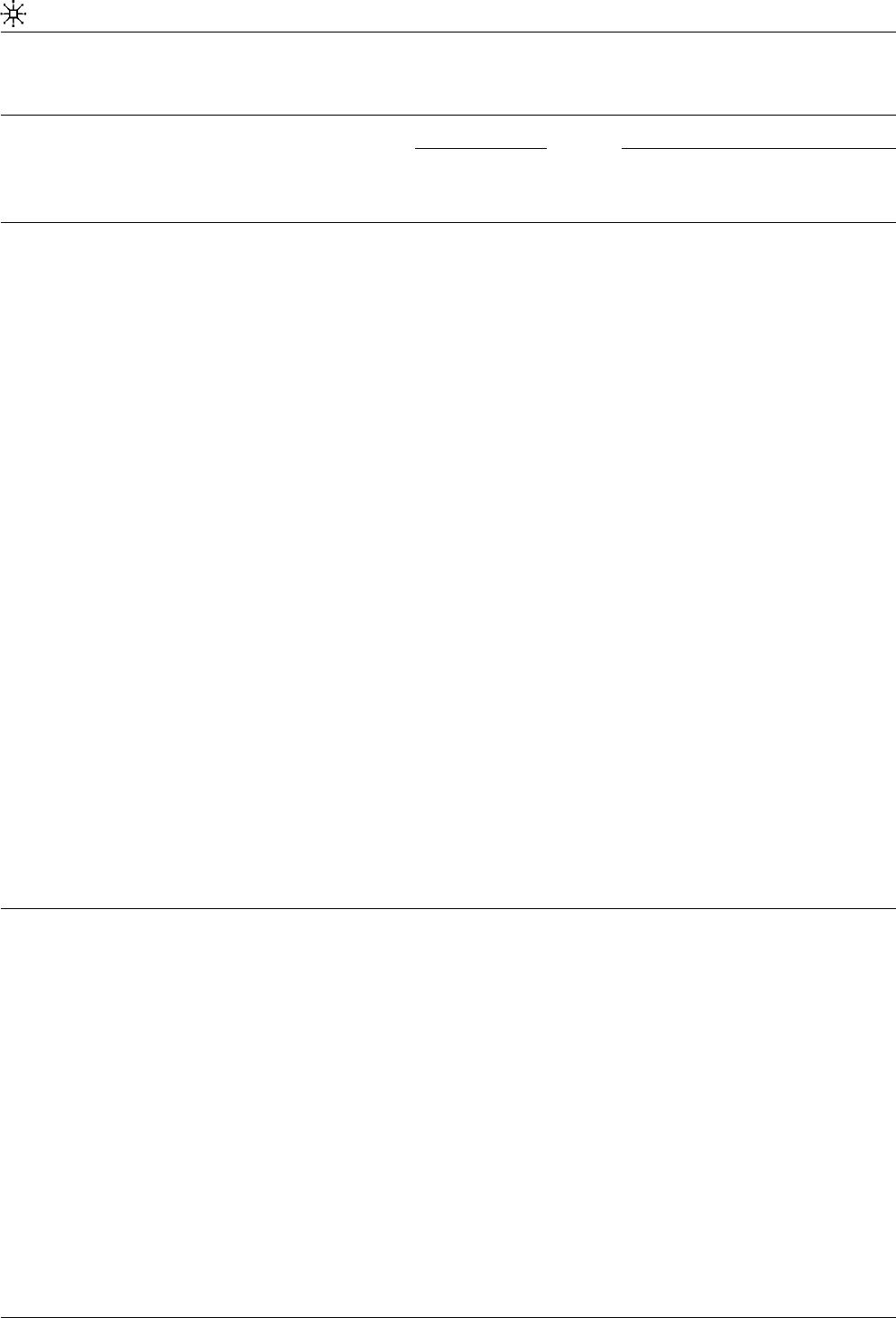

Table 2 summarizes the impacts of y6662 on

Japanese MNEs’ abnormal returns for our selected

event dates. The table reports CARs, as a percen-

tage, for two windows (1, 0) and (1, þ 1), along

with their Z scores, ratio of negative to positive

returns, and binomial Z scores.

As the table shows, our event study results closely

follow their predicted signs, with the impacts being

negative and significant for almost all event dates.

In addition, both the y6662 penalty regulations

(13 January 1993, 2 February 1994) and their

accompanying contemporaneous documentation

requirements (2 February 1994, 8 July 1994) have

significant, negative impacts on CARs. This

provides empirical support for H1 (the penalty

reduces MNE profitability) and H3 (documentation

requirements reduce profitability). The policy

impacts are also larger at the beginning of the

period; as the surprise factor should deteriorate over

time, one would expect the CARs to be smaller for

later dates.

There are three anomalies where H1 is not

confirmed by the empirical results. The Pickle

hearings (10 July 1990) had no effect on CARs.

Event study methodology depends on surprise: an

event affects abnormal returns only if it is a surprise

Table 1 Japanese multinationals with ADRs and subsidiaries in

the United States, 1990–1999

No. PERMNO TICKER Company name

1 21152 CANNY Canon Inc.

2 26060 CSKKY CSK Corp.

3 28303 DAIEY Dai Ei Inc.

4 37867 FUJIY Fuji Photo Film

5 46085 IYCOY ITO Yokado Ltd

6 46309 JAPNY Japan Air Lines

7 47897 KNBWY Kirin Brewery Ltd

8 51087 MKTAY Makita Electric W

9 51131 SNE Sony Corp.

10 53727 MC Matsushita Electric

11 54579 MITSY Mitsui & Co Ltd

12 55782 NIPNY NEC Corp.

13 57681 NSANY Nissan Motors

14 59344 KUB Kubota Corp.

15 59424 PIO Pioneer Electronic

16 59555 HMC Honda Motor Ltd

17 61778 KYO Kyocera Corp.

18 64231 HIT Hitachi Limited

19 64362 TDK TDK Corp.

20 68823 SANYY Sanyo Electronic

21 75811 MBK Mitsubishi Bank

22 76428 TKIOY Tokyo Marine & Fire

23 76655 TOYOY Toyota Motor Corp.

24 81331 WACLY Wacoal Corp.

Talk softly but carry a big stick Lorraine Eden et al

403

Journal of International Business Studies

to investors. Although the hearings were widely

publicized, within the Japanese MNE community

this would not have been ‘new news’, so the lack of

market reaction is to be expected. The disclosure

standard was raised on 17 March 1994, but this

event was also either ignored or anticipated by the

market. Lastly, the DHL penalty (30 December

1998), although widely reported in the financial

press, was not reflected in CARs, presumably

because there was no surprise factor attached to

the penalty announcement.

We therefore conclude that the empirical evi-

dence provides strong support for our hypotheses.

Subgroup analysis

We now turn to the second stage of our analysis.

Following the research methodology laid out in

McWilliams and Siegel (1997), we perform three

post hoc tests to further explore the relationship

between tax penalties and MNE profits.

The first test is a subgroup analysis of all the

dates, separating our 24 Japanese MNEs into two

groups: automotive and electronics (A&E, eight

firms) and all other firms. The A&E group were

heavily targeted during the 1990 Pickle hearings as

the foreign firms most heavily engaged in transfer

price manipulation and underpayment of US taxes.

Table 2 Impact of y6662 on the abnormal returns of US ADRs by Japanese multinationals

Results Window Actual effect on CAR

Date Event Predicted

by

theory

Actual

results

(Z o5%)

CAR Z Pos:Neg Binomial Z

20 Feb 1990 IRS audits foreign MNEs for tax

underpayment.

(1,0) 2.87% 6.22*** 0:24 4.40***

(1,+1) 5.12% 9.02*** 0:24 4.4.0***

10 Jul 1990 Pickle hearings on underpayment of

US tax by foreign MNEs.

+(1,0) 0.57% 1.17 16:8 2.04*

(1,+1) 0.91% 1.48

w

18:6 2.86**

4 Mar 1991 y6662 proposed penalty regulations

issued (except for transfer pricing section).

(1,0) 4.96% 7.47*** 0:24 4.57***

(1,+1) 6.66% 8.05*** 0:24 4.57***

13 Jan 1993 y 6662 proposed transfer pricing

penalty regulations. Documentation

required for ‘reasonable cause and good

faith’ exemption.

(1,0) 1.99% 3.47*** 2:22 4.05***

(1,+1) 1.76% 2.59** 3:21 3.64***

2 Feb 1994 y6662 temporary regulations outline penalty

and documentation requirements.

(1,0) 0.19% 0.30 10:14 0.29

(1,+1) 1.87% 3.00** 6:18 1.93*

17 Mar 1994 y6662 temporary regulations raise

disclosure standard, impose cost burden.

0(1,0) 0.40% 0.71 12:12 0.56

(1,+1) 0.35% 0.67 9:15 0.68

8 Jul 1994 y6662 temporary regulations

provide documentation list, clarify

requirements.

(1,0) 1.19% 2.38** 5:19 2.50**

(1,+1) 0.57% 0.78 9:15 0.87

11 Mar 96 Transfer pricing penalty oversight

committee created to coordinate

penalties.

(1,0) 1.07% 1.81* 6:18 2.27*

(1,+1) 1.06% 1.40

w

9:15 1.05

17 Sep 1997 First y6662 transfer pricing penalty

announced.

(1,0) 1.31% 3.10*** 7:17 2.10*

(1,+1) 0.45% 1.03 10:14 0.87

30 Dec 1998 40% transfer pricing penalty against

DHL Corporation is sustained by

US Tax Court.

0(1,0) 0.25% 0.38 15:9 1.46

(1,+1) 0.04% 0.18 11:13 0.18

Asterisks show significance levels using a two-tailed test, where

w

o0.10, *o0.05, **o0.01, ***o0.001.

Talk softly but carry a big stick Lorraine Eden et al

404

Journal of International Business Studies

Therefore, these firms were the most likely targets

for y6662.

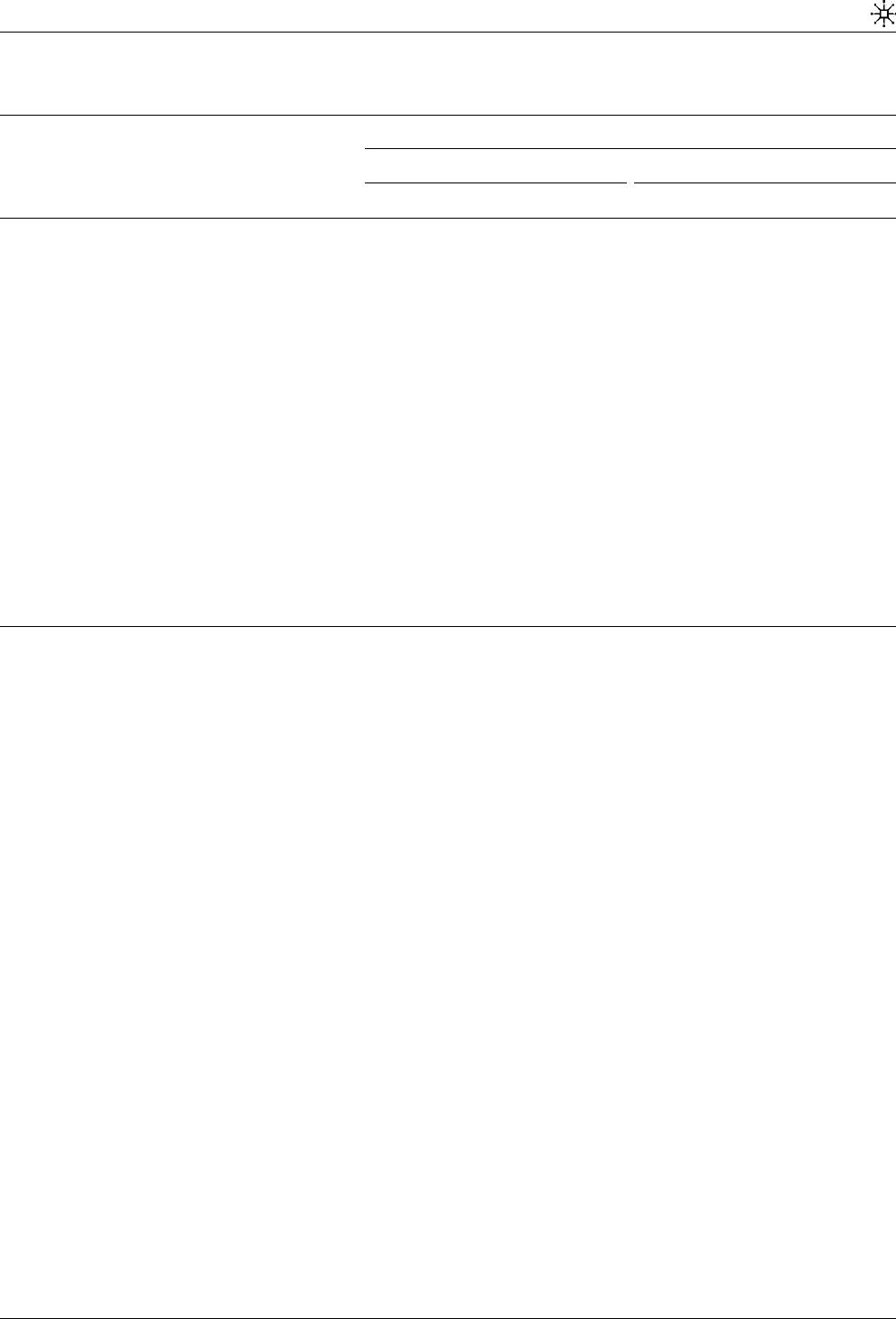

Table 3 reports CARs by subgroup for the seven

significant event dates from Table 2. Although both

groups show negative, significant Z, and binomial

Z scores for most dates, two items are noteworthy.

First, the negative CARs are larger for the non-A&E

group. Second, the A&E CARs are significant only

in the early years, whereas the non-A&E CARs are

significant in all time periods. Paired means tests of

the CARs for the two groups show significant

differences between the two groups, using either a

2-day (po0.0328) or 3-day (po0.0518) window or a

combined window (po0.0012).

The most likely explanation for the differences

between the two subgroups is the lack of policy

surprise for the A&E firms. As the A&E group has

been audited continuously since the late 1980s, and

several A&E firms were in tax court by the mid-

1990s, the penalty proposals would not have been a

surprise for these firms. The group most surprised

by y6662 should have been the non-A&E group,

which accords with our event study results in

Table 3, and our paired means comparison test. In

practice, the actual penalties levied on the A&E

group might be higher, but event study methodol-

ogy does not measure the actual income lost, only

the impact on market valuations when investors are

surprised.

Cross-section and panel data tests

Cross-section tests

Our second post hoc test examines the cross-

sectional variation in CARs within our sample. H2

suggests that the penalty should have the most

negative impact on MNE after-tax profits in cases

where the probability of the penalty is high and the

penalty is likely to be large. These two cases are

most likely where the MNE has large intrafirm sales,

is highly profitable before tax, pays little or no US

taxes, and is a member of the A&E group.

Our dependent variable is CAR3, the 3-day

cumulative abnormal returns. In the absence of

firm-level data on intrafirm sales, we use the

natural log of total sales, LNSALE, as a proxy for

intrafirm sales. LNSALE also proxies for size of the

MNE, which would accord with the hypothesis that

large MNEs are more likely to attract attention from

Table 3 Subgroup analysis of abnormal returns

Actual effect on CAR

Autos & electronics group (n¼8) All other Japanese MNEs (n¼16)

Date Event Window CAR Z Pos:Neg Binomial Z CAR Z Pos:Neg Binomial Z

20 Feb 1990 IRS audits foreign MNEs

for tax underpayment

(1,0) 2.72% 3.55*** 0:8 2.58** 2.94% 5.11*** 0:16 3.57***

(1,+1) 5.02% 5.43*** 0:8 2.58** 5.16% 7.21*** 0:16 3.57***

4 Mar 1991 y6662 proposed regulations (1,0) 4.04% 3.76*** 0:8 2.65** 5.42% 6.49*** 0:16 3.73***

(1,+1) 5.31% 3.96*** 0:8 2.65** 7.34% 7.06*** 0:16 3.73***

13 Jan 1993 y6662 proposed transfer

pricing regulations

(1,0) 1.86% 2.13* 0:8 2.77** 2.06% 2.74** 2:14 3.00**

(1,+1) 2.32% 2.03* 1:7 2.06* 1.48% 1.73* 2:14 3.00**

2 Feb 1994 y6662 temporary regulations (1,0) 0.86% 0.78 5:3 0.89 0.72% 0.92 5:11 0.99

(1,+1) 1.16% 1.23 4:4 0.18 2.23% 2.80** 2:14 2.51**

8 Jul 1994 Document list (1,0) 1.46% 1.68* 1:7 2.04* 1.06% 1.73* 4:12 1.62

w

(1, +1) 1.03% 0.98 3:5 0.63 0.34% 0.27 6:10 0.62

11 Mar 1996 Transfer pricing oversight

committee

(1,0) 0.12% 0.24 3:5 0.63 1.55% 2.05* 3:13 2.34**

(1,+1) 0.02% 0.04 5:3 0.79 1.58% 1.69* 4:12 1.84*

17 Sep 1997 First y6662 transfer pricing

penalty

(1,0) 0.39% 0.65 3:5 0.62 1.77% 3.34*** 4:12 2.13*

(1,+1) 0.27% 0.21 3:5 0.62 0.81% 1.42

w

7:9 0.63

Asterisks show significance levels using a two-tailed test, where

w

o0.10, *o0.05, **o0.01, ***o0.001.

Talk softly but carry a big stick Lorraine Eden et al

405

Journal of International Business Studies

the IRS. We expect a negative relationship between

LNSALE and CARs.

PPM, the pre-tax profit margin, and the Berry

ratio (BERRY) are used as measures of pre-tax

profitability. The Berry ratio is a well-known profit-

ability measure used by transfer pricing profes-

sionals and the IRS as possible evidence of transfer

price manipulation; it is the ratio of sales minus

cost of goods sold, divided by selling and general

administrative expenses.

16

TXASSET, the ratio of total US taxes paid divided

by total assets, is used as a proxy for taxes paid. Low

tax/asset ratios have been used by the IRS as

evidence of transfer price manipulation (e.g. Heck,

1990; Eden, 1998). Low tax/asset ratios should

trigger investigations by the IRS, raising the prob-

ability of the transfer pricing penalty. We therefore

expect a positive relationship between TXASSET

and CARs. Lastly, a dummy variable A&E is added

for firms with primary SIC code in the automotive

and electronics sectors.

Our model is therefore of the form

CAR3 ¼a

0

þ a

1

LNSALE þ a

2

PPM þ a

3

BERRY

þ a

4

TXASSET þ a

5

A&E þ x ð2Þ

Table 4 reports our results for the cross-section

tests, by event date. Data for the independent

variables are taken from Compustat’s ADR set for

1990–98. Where variables are missing, the firm is

deleted from our data set: thus the number of firms

varies for each of the regressions. In addition, a

pooled time-series, cross-section test is conducted

for the 19 firms with complete information for all

years. All variables, including the dependent vari-

able,

17

are centered at mean zero and the resulting

variance inflation factors (VIFs) for all regressions

are close to 1.0 so that multicollinearity is not a

problem (except in the moderator analysis where

high VIFs are inevitable). We use the REGRESS

ROBUST technique in STATA/SE 8.0. This technique

uses the Huber/White/sandwich estimator of var-

iance in place of traditional OLS estimators: this

generates ‘consistent standard errors even if the

data are weighted or the residuals are not identi-

cally distributed’ (STATA, 2003, Vol 3, 328).

Although we do have predictions for the direction

of expected effects, we use a conservative two-tailed

t-test.

The general fit of our model is very good, with all

equations having significant F statistics. Looking

first at the individual cross-section events, the most

consistent result is firm size; LNSALE is negative

and significant in three of the six dates, as

hypothesized. The A&E variable is positive for all

years, but significant on only one date (13 January

1993), contrary to our original expectations, but in

accordance with our subgroup analysis. BERRY is

negative and significant for two dates, but positive

and significant for a third (13 January 1993);

Table 4 Cross-section time-series analysis of cumulative abnormal returns

Pooled dates

20 Feb

1990

4 Mar

1991

13 Jan

1993

2 Feb

1994

11 Mar

1996

17 Sep

1997

(1) (2) (3)

LNSALE 0.0167

w

0.0002 0.0165* 0.0323

w

0.0038 0.0230 0.0093

w

0.0089 0.0086

A&E 0.0146 0.0186

w

0.0025 0.0000 0.0157 0.0015 0.0107

w

0.0114

w

0.0113

w

BERRY 0.0005 0.0008** 0.0007

w

0.0011 0.0007 0.0026*** 0.0001 0.0067* 0.0101**

PPM 0.0221 0.0776 0.2766* 0.0670 0.0389 0.3008 0.0189 0.0301 0.0360

TXASSET 0.1973 0.4348* 1.0544** 0.7751** 0.3064 0.9554

w

0.0661 0.4279 0.7150*

BERRY TXASSET 0.2733* 0.4106**

PPM TXASSET 3.3724

w

YR90 0.0474*** 0.0492*** 0.0498***

YR91 0.0568*** 0.0585*** 0.0588***

YR93 0.0082 0.0091 0.0095

YR94 0.0107 0.0136 0.0152

YR96 0.0002 0.0001 0.0019

Constant 0.0316*** 0.0414*** 0.0111** 0.0061 0.0120* 0.0183* 0.0205*** 0.0109 0.0027

Number of obs. 22 22 22 21 21 23 114 114 114

R

2

0.3321 0.5167 0.4871 0.2245 0.1645 0.3818 0.4267 0.4400 0.4517

F statistic 4.42* 65.53*** 4.23* 14.72*** 2.87

w

9.41*** 9.85*** 9.13*** 9.21***

F DIST 5.20* 6.26**

Asterisks show significance levels using a two-tailed test, where

w

o0.10, *o0.05, **o0.01, ***o0.001.

Talk softly but carry a big stick Lorraine Eden et al

406

Journal of International Business Studies

interestingly, that is the only date where PPM is

significant, suggesting that a moderator effect may

be at work. TXASSET is significant in four of the six

years; however, its sign switches (positive for two

years, negative for two), so that no clear relation-

ship emerges between CARs and the tax/asset ratio.

In addition, we ran a series of regression diag-

nostic tests (DFITS, Cook’s Distance, WELSCH

distance) to check for possible confounding effects

from outliers (STATA, 2003, Vol 3, 373–377); none

appeared. As the number of firms in our cross-

section regressions is small (N¼ 22 or 23), we also

employed bootstrapping techniques (STATA, 2003,

Vol 1, 112–127; Mooney and Dulal, 1993).

18

Setting

the number of replications at 1000, we found that

the bootstrap bias estimate relative to the observed

standard error, for each independent variable in

each regression, was always a small percent of the

bootstrapped standard error, and that our observed

standard error always lay within the bootstrapped

confidence interval. We therefore concluded that

the underlying distribution was approximately

normal and our results were not affected by the

small sample size.

Pooled cross-section time-series tests

In the pooled cross-section time-series regression,

column 1 simply repeats the individual year

regressions, with the addition of year dummy

variables. Only two variables are significant:

LNSALE (negative) and A&E (positive), which is

consistent with our individual date results. In

column 2 we add one moderator term, BER-

RY TXASSET, to test our hypothesis that high

profitability, coupled with low tax payments, is a

better predictor of abnormal returns than either

variable separately. Owing to the multicollinearity

induced by adding the moderator term, the signs

on the individual variables are somewhat suspect.

However, it is interesting to note that both BERRY

and the moderator variable BERRY TXASSET are

negative and significant, suggesting that MNEs

with high profits and low taxes earned negative

abnormal returns over the six-event period. The F

DIST test is also significant (F¼5.20), implying that

there is a moderator effect at work. The F DIST test

is even stronger in column 3 when we add

PPM TXASSET as a second moderator. TXASSET

now becomes significant and negative, with a

weakly positive moderator term. In all the three

pooled regressions, the 1990 and 1991 year dummy

variables are highly significant, suggesting that

earlier event dates had more impact on abnormal

returns than later dates. This coincides with our

expectations: because the surprise factor and the

relative significance of the policy changes decline

over time, we expect a greater impact earlier on.

19

Looking across the nine regressions, some pat-

terns are evident. Abnormal returns are negatively

related to LNASSET and BERRY, as expected. CARs

are also positively (not negatively) related to A&E,

contrary to our original predictions but in accor-

dance with our subgroup analysis. TXASSET is a

significant predictor of CAR, but its sign varies; one

reason may be that TXASSET moderates the

relationship between the profitability ratios and

abnormal returns. The two earliest event dates (20

February 1990 and 4 March 1991) are negatively

and significantly related to abnormal returns,

whereas later dates are not statistically significant.

This accords with event study methodology where-

by surprise is critical to the generation of abnormal

returns.

We conclude that our post hoc analyses provide

strong support for our hypotheses. Cumulative

abnormal returns are affected by the size of the

firm (), membership in the A&E group ( þ ), and

pre-tax profitability (). MNEs with high profits

and low tax-asset ratios earned negative abnormal

returns. The impact of the penalty on CARs was

strongest at the beginning of the 1990s, and

became less important as the element of surprise

disappeared.

As final checks on our cross-section, time-series

regressions, we ran regression diagnostic tests for

outliers, without finding any problems. We also

employed bootstrapping techniques (number of

replications¼1000) and concluded that our results

were robust to sample size.

Market valuation of Japanese parents

As a third test, we examined the impact of US

transfer pricing penalty announcements on the

stock market returns of the Japanese parent firms,

using daily stock prices on the Tokyo Stock

Exchange.

20

While we expected the major impact

of the US penalty to be on the abnormal returns of

Japanese subsidiaries in the US (and therefore

reflected in their US ADRs), there was some

possibility, albeit remote, that US tax penalties

could have negatively affected the market returns

of Japanese parent firms on the Japanese stock

market.

Using EVENTUS, external datasets were required

to perform event studies with non-CRSP data. We

retrieved the daily stock prices and market indices

Talk softly but carry a big stick Lorraine Eden et al

407

Journal of International Business Studies