METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS B VOLUME 28B, FEBRUARY 1997—47

Effect of FeO in the Slag and Silicon in the Metal

on the Desulfurization of Hot Metal

P.K. IWAMASA and R.J. FRUEHAN

Work has been conducted to investigate the effects of FeO in the slag and silicon in the metal on

hot metal desulfurization. Laboratory experimental results show that FeO decreases and silicon in-

creases the rate of desulfurization. Silicon in the metal is consumed by the reduction of FeO and

also by the desulfurization reaction. A mathematical kinetic model was developed to describe both

the effects of silicon and FeO on desulfurization for the laboratory scale. The model predicts the

sulfur and silicon content in the metal and the FeO and sulfur content in the slag as a function of

time. It is based on four-component simultaneous mass transfer: sulfur and silicon in the metal and

FeO and sulfur in the slag. Experimental results, the development of the kinetic model, and a com-

parison of the model and experimental results are presented.

I. INTRODUCTION

THE desulfurization of hot metal is a vital part of the

steelmaking process since sulfur in many steel products is

detrimental. In general, desulfurizing hot metal is more ec-

onomical than desulfurizing steel, and about 90 pct of the

metal produced in the iron blast furnace is desulfurized be-

fore it is sent to be processed in a steelmaking furnace. A

common practice is the injection of a desulfurizing reagent

through a lance. During injection, there are two sites at

which sulfur is removed from the metal. Sulfur is removed

by the reagent particles that are injected and rise in the

metal bath and also by the slag that accumulates at the top

of the metal. These reaction sites can be studied indepen-

dently and are referred to as the transitory (rising particles)

and the permanent contact (top slag) reactions. It has been

shown that when the same amount of slag is either simply

added to the top of the metal or injected, the sulfur content

of the metal reaches the equilibrium amount at about the

same time after the slag is introduced.

[1,2]

The present study

will focus only on the top slag reaction as results obtained

from these findings can be used to predict the behavior

during the injection desulfurization process. A subsequent

publication will utilize the basis of the model presented

here to demonstrate the effect of FeO in the slag and silicon

in the metal on desulfurization in actual industrial practice.

Although hot metal desulfurization is a mature process,

the effects of FeO in the slag have never been quantitatively

assessed. The FeO present in the desulfurizing unit origi-

nates from two main sources. The first source is slag carried

over from the iron blast furnace and the second is hot metal

oxidized during tapping from the blast furnace and during

transportation to the desulfurization station. The presence

of FeO in the slag during desulfurization hinders both the

thermodynamics and kinetics of the desulfurization process.

P.K. IWAMASA, formerly Graduate Student, Department of Materials

Science and Engineering, Carnegie Mellon University, is Research

Associate, BHP Research, New South Wales 2287, Australia. R.J.

FRUEHAN, Professor, is with the Department of Materials Science and

Engineering, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA 15213.

Manuscript submitted October 5, 1995.

This can be demonstrated in the definition of the sulfur

partition ratio, L

S

, a measure of the thermodynamic ability

of a slag to contain sulfur.

[3]

(pct S) fC

SS

L 55 [1]

S

[pct S] hK

O2

where

(pct S) 5 weight percent of sulfur in the slag;

[pct S] 5 weight percent of sulfur in the metal;

f

S

5 activity coefficient of sulfur in metal relative to the

1 wt pct standard state;

C

S

5 sulfide capacity of the slag (as defined by Rich-

ardson and Withers

[5]

);

h

O

5 Oxygen potential of the system; and

K

2

5 equilibrium constant for the slag and gas equilib-

rium:

11

S (g) 1 O 5 O (g) 1 S [2]

22

22

FeO in the slag effects the sulfur partition ratio by con-

trolling the oxygen potential at the interface between the

slag and metal. This can be demonstrated by the chemical

equilibrium between FeO in the slag and the liquid iron and

the corresponding equilibrium constant expression:

(FeO) 5 Fe (I) 1 O [3]

ah

Fe O

K 5 [4]

3

i

a O

Fe

where

a 5 activity of liquid iron; and

Fe

i

a 5 activity of FeO in the slag at the interface.

FeO

By substituting Eq. [4] into Eq. [1], it can be seen that the

sulfur partition ratio is inversely proportional to the amount

of FeO in the slag at the interface for a fixed value of C

S

.

1

L

a

[5]

S

(pct FeO)

i

As the amount of FeO in the slag at the interface increases,

the thermodynamic ability of the slag to contain sulfur de-

48—VOLUME 28B, FEBRUARY 1997 METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS B

Fig. 1—Schematic of the experimental apparatus used for kinetic study.

creases for a fixed value of C

S

. In reality, C

S

may be a

function of FeO and S content, but this effect is small.

[4]

The aim of this work is to determine the kinetics of de-

sulfurization in the presence of silicon in the metal and

simultaneous reduction of FeO from lime (CaO) based slags

according to the following chemical reactions:

2S 1 2(CaO) 1 Si 5 2(CaS) 1 (SiO ) [6]

2

2(FeO) 1 Si 5 2Fe (I) 1 (SiO ) [7]

2

A mathematical kinetic model is also presented to describe

the time dependence of the concentration of silicon and

sulfur in the metal and FeO in the slag.

II. EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURE

The experimental work included trials using 300 g of

metal and 30 g of slag of the following chemistry.

Metal: carbon saturated

0.12, 0.45 pct Si

0.14 pct S

master slag: 50 pct CaO

(premelted) 45 pct SiO2

5 pct MgO

slag addition: 0 to 5 pct FeO

Alloys, slags, and FeO used in the experiments carried out

in this study were prepared as follows.

Master Alloys. An Inductotherm induction furnace was

used to melt the metal alloys. Iron chips or lumps were

placed in a graphite crucible and melted. Silicon in the form

of ferro-silicon (50 pct Si) was added to the liquid metal

and allowed to equilibrate for a few minutes. Sulfur was

then added in the form of granular ferrous sulfide (FeS) and

allowed to equilibrate for another few minutes. The metal

was then cast into graphite crucibles (29-mm i.d., 50-mm

o.d., and 305-mm height) and left to cool overnight. Once

at room temperature, the resulting casting was cut, sand-

blasted, and ultrasonically cleaned to remove any surface

residue.

Slag. One kilogram of the mixture of reagent grade pow-

ders (50 pct CaO, 45 pct SiO

2

, 5 pct MgO) was mixed and

placed in a high density MgO crucible (96-mm i.d., 102-

mm o.d., and 152-mm height). The crucible was placed in

a Lindberg molybdenum disilicide resistance box furnace

and heated to a temperature of 1425 7C at a rate of 2 7C

per minute. The furnace was stabilized at 1425 7C for 30

minutes, the slag and crucible were furnace cooled, and the

slag was crushed.

FeO. FeO was prepared using a Lindberg silicon carbide

resistance tube furnace. About 100 g of reagent grade Fe

2

O

3

powder was placed in a steel crucible (39-mm i.d., 45-mm

o.d., and 128-mm height) and placed in the reaction tube.

The top was sealed and an alumina lance was placed

through the lid to about 1 cm from the powder surface. A

gas mixture of 50/50 CO/CO

2

was flowed through the lance

at a rate of 2 cc/s. The furnace was heated to a temperature

of 1150 7C and kept there for about 12 hours; it was then

cooled to about 800 7C. The gas atmosphere was changed

to argon for a 10-minute purge; then the cover of the fur-

nace was opened and the crucible removed and quenched

in a high flow rate of argon. X-ray diffraction analysis

showed that the end product was converted (more than 99

pct) to FeO.

A. Kinetic Experiments

Experiments were run using a 10 kW Ameritherm in-

duction furnace. A schematic of the apparatus is shown in

Figure 1. The metal was placed in a magnesia crucible (in-

side diameter 32 mm) and gradually heated to 1450 7C.

The experimental temperature was periodically measured

with an optical pyrometer. The chamber was closed to the

atmosphere and a low flow rate of argon (0.5 cc/s) was

maintained within the furnace during the experiment. A

graphite ring was used as a susceptor from the induction

field to heat the slag layer over the metal. The slag was

added by means of a funnel through the sample port, and

metal and slag samples were taken at varying times from

the time of slag addition. The metal samples were obtained

using silica suction tubes and the slag samples with notched

copper rods. The slag samples were chemically analyzed

for FeO (total iron, assumed to be in the form of FeO) by

METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS B VOLUME 28B, FEBRUARY 1997—49

Table I. Starting Composition of Slag and Metal for

Kinetic Experiments

Run

Identification [Pct S] [Pct Si] (Pct FeO)

S1 0.141 0.12 0.0

S2 0.143 0.12 5.0

S3 0.143 0.12 3.0

S4 0.143 0.12 1.0

S5 0.145 0.41 0.0

S6 0.144 0.43 5.0

S7 0.147 0.47 3.0

S8 0.147 0.44 1.0

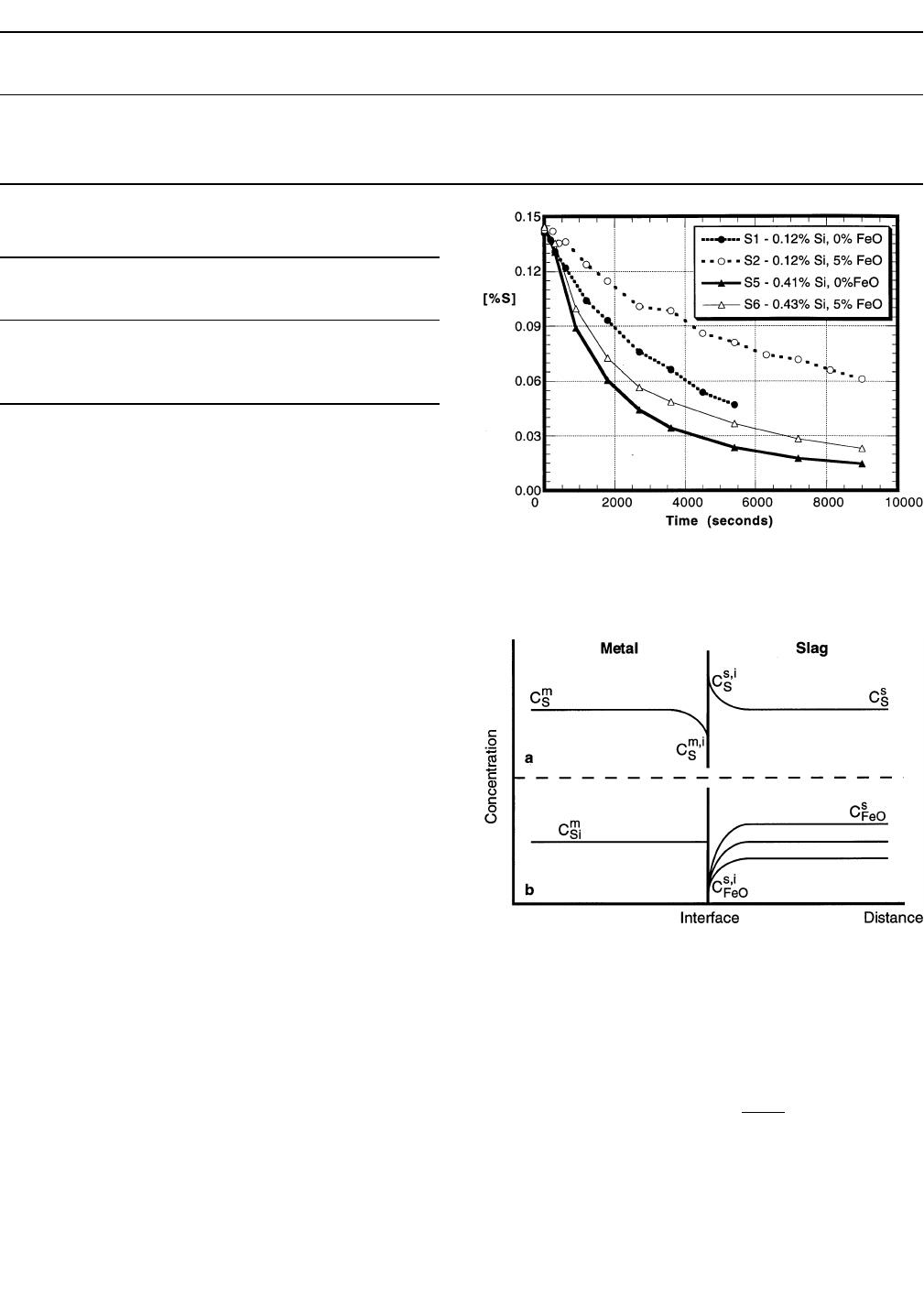

Fig. 2—Effect of FeO on desulfurization: experimental results for metal

sulfur content as a function of time for initial slag FeO contents between

0 and 5 pct.

Fig. 3—FeO reduction: experimental results for slag FeO content as a

function of time for initial slag FeO contents between 1 and 5 pct.

redox titration with K

2

Cr

2

O

7

. The metal samples were an-

alyzed for carbon and sulfur using a LECO* Analyzer pro-

*LECO is a trademark of LECO Corporation, St. Joseph, MI.

vided by the AISI Pilot Plant (Universal, PA). Silicon con-

tents in the metal samples were determined using a wet

chemical technique at Spectrochemical Laboratories (Pitts-

burgh, PA).

B. Constant Volume Pressure Increase Experiments

Experiments utilizing the constant volume pressure in-

crease (CVPI) technique were carried out to investigate if

there was any gas evolution between the slag and metal

from experiments similar to those done in the induction

furnace. The motivation for these experiments was to jus-

tify the mass transfer coefficients that were fit to the math-

ematical model. These experiments were also used to prove

the assumption that the reduction of FeO in the slag by

carbon dissolved in the metal producing carbon monoxide

gas did not appreciably affect the mass balances used in

the development of the mathematical model.

A Lindberg silicon carbide resistance furnace was used

with a mullite reaction tube (48-mm i.d., 54-mm o.d., 610-

mm length, and closed round at bottom). An alumina ped-

estal was place at the bottom of the tube, and the MgO

crucible containing the metal was seated on the pedestal. A

mullite guiding tube (25-mm i.d., 32-mm o.d., and 457-mm

length) cemented (AREMCO* Cermabond 503) to the

*AREMCO is a trademark of Aremco Products, Inc., Ossining, NY.

MgO crucible extended through the length of the furnace.

The furnace was sealed and the temperature was slowly

increased from room temperature to 1450 7C under an ar-

gon atmosphere. Once 1450 7C was obtained, the argon

flow was stopped. Calibration of the equipment was carried

out by injecting a known volume of air into the furnace

and the response recorded by the data acquisition system.

Once the calibration was completed, a port in the lid was

opened and a pin sample was obtained. The slag was then

added and the port quickly sealed. The exit port of the lid

was connected to a pressure transducer (Daytronic 502)

which was connected to an analog to digital converter and

a data acquisition system. The data collected were in the

form of volts vs time, and volts were converted to moles

of gas using the calibration curve.

III. RESULTS

Table I outlines the starting composition of the slag and

metal for the experiments carried out in this series. The

normalized sulfur content of the metal as a function of time

is shown in Figure 2 for experiments S1 through S4. These

data clearly show the dependence of the desulfurization

ability of a slag as a function of the amount of FeO added

to the slag. In these experiments, the initial silicon content

of the metal is 0.12 pct Si. As the initial amount of FeO in

the slag increases, the desulfurization ability of the slag

decreases as does the rate of sulfur removal. Figure 3 shows

the concentration of FeO in the slag as a function of time.

For the results presented here, the initial silicon (0.12 pct

Si) and sulfur (0.14 pct S) contents were consistent. As seen

from this plot, FeO is reduced out of the slag rather quickly

and the equilibrium value for the concentration of FeO in

the slag is quite low.

Figure 4 displays the time dependence of silicon concen-

tration in the metal for the same series of experiments men-

tioned previously. As expected from the FeO reduction

reaction and the results for FeO content in the slag, as the

amount of FeO in the slag increases, more silicon is con-

sumed. Silicon is stoichiometrically consumed in both the

50—VOLUME 28B, FEBRUARY 1997 METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS B

Fig. 4—Silicon removal during desulfurization: experimental results for

metal silicon content as a function of time for initial slag FeO contents

between 0 and 5 pct.

desulfurization reaction and the FeO reduction reaction.

Mass balance calculations for silicon consumption for the

series of experiments, where the initial silicon content in

the metal is 0.12 pct, are presented in Table II. These cal-

culations are based on the initial and final values of the

constituents that were analyzed. As evident from the cal-

culations presented in Table II, the mass balances between

silicon in the metal are reasonable within a maximum 10

pct discrepancy. The contribution of silicon consumption

from FeO and sulfur varies depending on the initial FeO

content of the slag and is presented in Table III for the

same series of experiments.

Figure 5 shows both the effects of FeO in the slag and

silicon in the metal on desulfurization. A greater silicon

content in the metal provides for better and more rapid

sulfur removal for both cases where the slag contains 5 pct

FeO and no FeO.

IV. MATHEMATICAL KINETIC MODEL

To better understand and analyze the results of the lab-

oratory experiments, a kinetic model was developed. This

section discusses the underlying assumptions that went into

the development of the mathematical model based on chem-

ical Reactions [6] and [7]. Sulfur, in the presence of silicon

in the metal, is removed by a lime based reagent, and FeO

in the slag is reduced by silicon in the metal. These as-

sumptions will be shown to be consistent with the experi-

mental results. The reduction of FeO in the slag by carbon

in the metal, as presented in the following chemical reac-

tion, is slow compared to the reaction between FeO and

silicon.

(FeO) 1 C 5 Fe (I) 1 CO (g) [8]

Reaction [8] was neglected in the mathematical model,

since it was determined to be relatively insignificant com-

pared to Reactions [6] and [7]. Previous investigators have

shown that Reaction [8] which involves three phases

(metal, slag, and gas) proceeds at a relatively slow rate by

means of gaseous intermediates.

[6,7,8]

It was found that for

a slag FeO content below about 2.5 pct, the rate is limited

by the chemical reaction rate at the gas/metal interface. For

slags with higher FeO contents, the reaction is controlled

by the kinetics of the chemical reaction at the slag/gas in-

terface. Kinetics of chemical reactions involving two phases

(slag and metal) are usually faster than three-phase reac-

tions. Typical slag/metal reactions are mass transfer con-

trolled in terms of elements diffusing through the slag and

the metal with very fast chemical kinetics at the interface.

The elimination of Reaction [8] in the mathematical model

is further discussed in the results for the CVPI experiments.

A. Assessment of All Possible Rate Controlling

Mechanisms

Before work on the model can commence, initial as-

sumptions about the controlling mechanisms to the preced-

ing reactions need to be made. There are many possible

rate controlling steps that may influence the reaction and

they are listed subsequently. It should be noted that com-

pounds in the slag phase diffuse as ions. For example, the

diffusing species for CaO are Ca

2+

and O

22

ions. However,

for charge neutrality, ‘‘CaO’’ can be considered as the

equivalent diffusing compound.

(1) Chemical reaction rate of Reference 6.

(2) Chemical reaction rate of Reference 7.

(3) Liquid-phase mass transfer of sulfur in the metal from

the bulk metal to the interface between the slag and

metal.

(4) Liquid-phase mass transfer of silicon in the metal from

the bulk metal to the interface between the slag and

metal.

(5) Liquid-phase mass transfer of CaO in the slag from the

bulk slag to the interface between the slag and metal.

(6) Liquid-phase mass transfer of ‘‘FeO’’ in the slag from

the bulk slag to the interface between the slag and

metal.

(7) Liquid-phase mass transfer of iron in the metal from

the interface between the slag and metal to the bulk

metal phase.

(8) Liquid-phase mass transfer of ‘‘SiO

2

’’ in the slag from

the interface between the slag and metal to the bulk

slag phase.

(9) Liquid-phase mass transfer of ‘‘CaS’’ in the slag from

the interface between the slag and metal to the bulk

slag phase.

B. Elimination of Possible Rate Controlling Mechanisms

To a first approximation, the chemical rates were as-

sumed to be fast, and the liquid phase mass transfers of

lime and silica in the slag are also assumed to be fast since

the slag composition is rich in both lime and silica which

results in a high driving force for mass transfer. As a par-

allel argument, liquid-phase mass transfer of iron in the

metal phase is taken to be fast. After elimination of the

previous mechanisms, the remaining possible rate control-

ling phenomena are the following:

(1) liquid-phase mass transfer of sulfur in the metal;

(2) liquid-phase mass transfer of silicon in the metal;

(3) liquid-phase mass transfer of ‘‘FeO’’ in the slag; and

(4) liquid-phase mass transfer of ‘‘CaS’’ or, more simply,

sulfur (S

22

) in the slag.

METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS B VOLUME 28B, FEBRUARY 1997—51

Table II. Mass Balance Calculations for Experiments S1 through S4

Run

Identification

Initial FeO

Content in the

Slag (Wt Pct)

Moles Silicon

Consumed (n

Si

)

Moles FeO

Reduced (n

FeO

)

Moles Sulfur

Lost (n

S

)

0.5 n

FeO

1 0.5 n

S

Difference between

(n

Si

) and

(0.5 n

FeO

1 0.5 n

S

)

S1 0 0.00471 0 0.00903 0.00452 1 5 pct

S2 5 0.01210 0.01920 0.00784 0.01350 210 pct

S3 3 0.01080 0.01200 0.00943 0.01070 1 1 pct

S4 1 0.00634 0.00316 0.00948 0.00632 1 0.3 pct

Table III. Relative Contribution to Silicon Consumption

for Experiments S1 through S4

Run

Identification

Initial FeO

Content in the

Slag (Wt Pct)

Pct Silicon

Consumed by

FeO Reduction

Pct Silicon

Consumed by

Desulfurization

S1 0 0 100

S257129

S335644

S412575

Fig. 5—Effect of FeO and silicon on desulfurization: experimental results

for metal sulfur content as a function of time for initial slag FeO contents

of 0 and 5 pct and initial silicon contents of 0.12 and 0.41/0.43 pct Si.

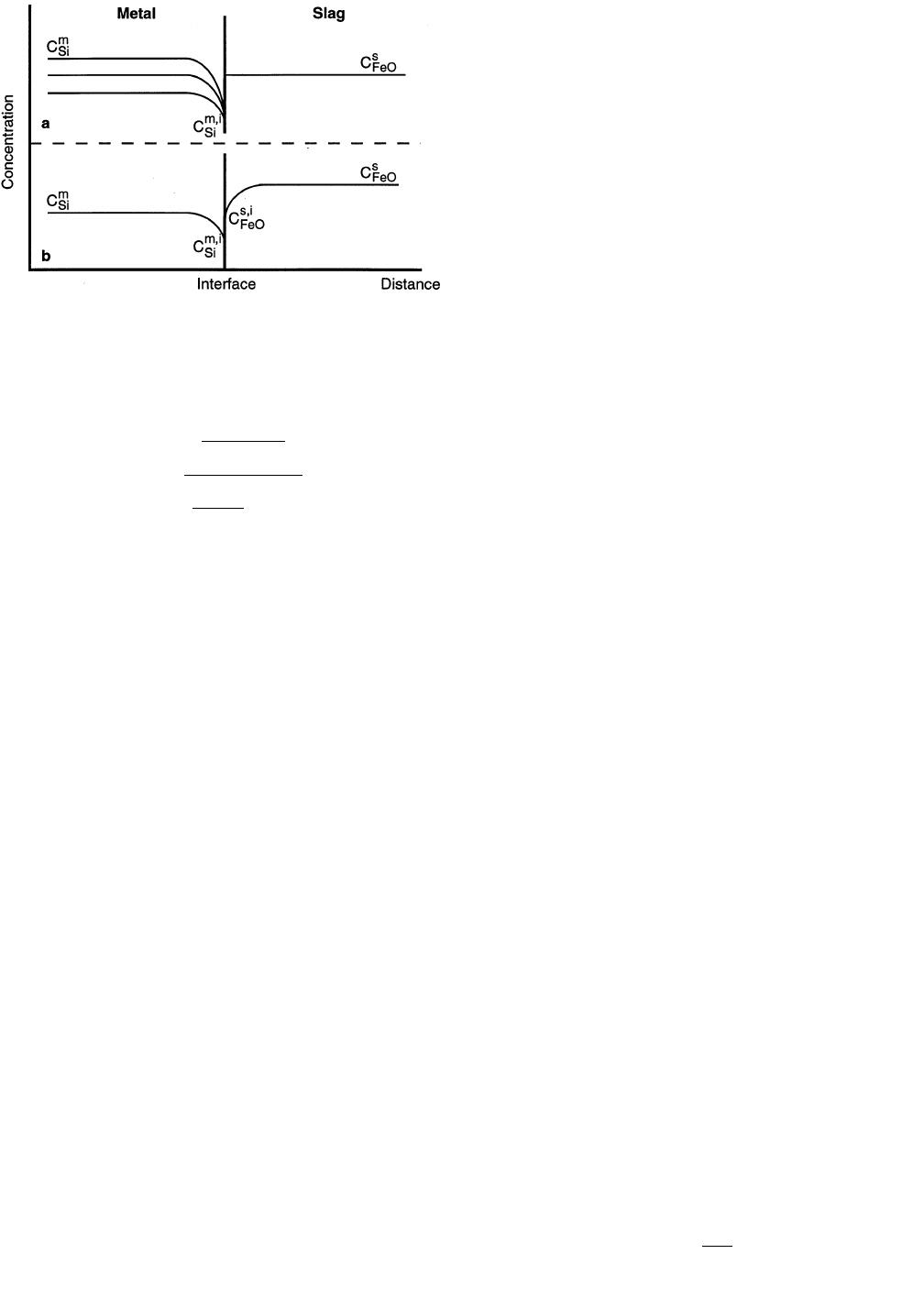

Fig. 6—Schematic concentration profile of elements in the slag and metal

phases near the interface: (a) sulfur in the metal and slag; and (b) silicon

in the metal and FeO in the slag based on mass transfer of FeO in the

slag.

The model is based upon the four mechanisms presented

earlier, and because the reactions are mass transfer con-

trolled, the flux of these elements and species at any given

time during the process can be defined as follows:

mmmm,i

J 5 mC2 C [9]

SS

~

SS

!

mmmm,i

J 5 mC2 C [10]

Si Si

~

Si Si

!

S S S S,i

J 5 mC2 C [11]

FeO FeO

~

FeO FeO

!

S S S,i S

J 5 mC

2

C [12]

SS

~

SS

!

where

5 flux of A in phase (slag or metal) b (moles cm

22b

J

A

s

21

);

5 mass transfer coefficient of A in phase b (cm s

21

);

b

m

A

5 concentration of A in bulk b phase (moles cm

23

);

b

C

A

and

5 concentration of A in the b phase at the interface

b,i

C

A

between the slag and metal (moles cm

23

).

C. Sulfur Mass Transfer

The mass transfer behavior of sulfur is well known and

has been extensively studied. It has been found that, in

general, it is the simultaneous mass transfer of sulfur in the

metal and sulfur in the slag that controls sulfur removal

from metal. This is represented by equating the sulfur fluxes

( ) and is schematically displayed in Figure 6(a).

ms

J 5 J

SS

mm m,iSs,iS

m (C 2 C ) 5 m (C 2 C ) [13]

SS S SS S

In Eq. [13], the surface concentrations of sulfur in the slag

and metal are related to each other by the sulfur partition

ratio. In the model, the concentration of sulfur in the slag

and metal are continually changing and the sulfur partition

ratio is defined at each time-step. The mass transfer of sul-

fur in the metal phase can be rewritten to include the mass

transfer of sulfur in the slag phase:

S

C

r

S m

mm

J 5 mC2 [14]

S0S

~!

L

r

S s

where

r

m

5 density of metal (g cm

23

);

r

s

5 density of slag (g cm

23

);

m

0

5 time-dependent overall mass-transfer coefficient for

sulfur in the metal:

52—VOLUME 28B, FEBRUARY 1997 METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS B

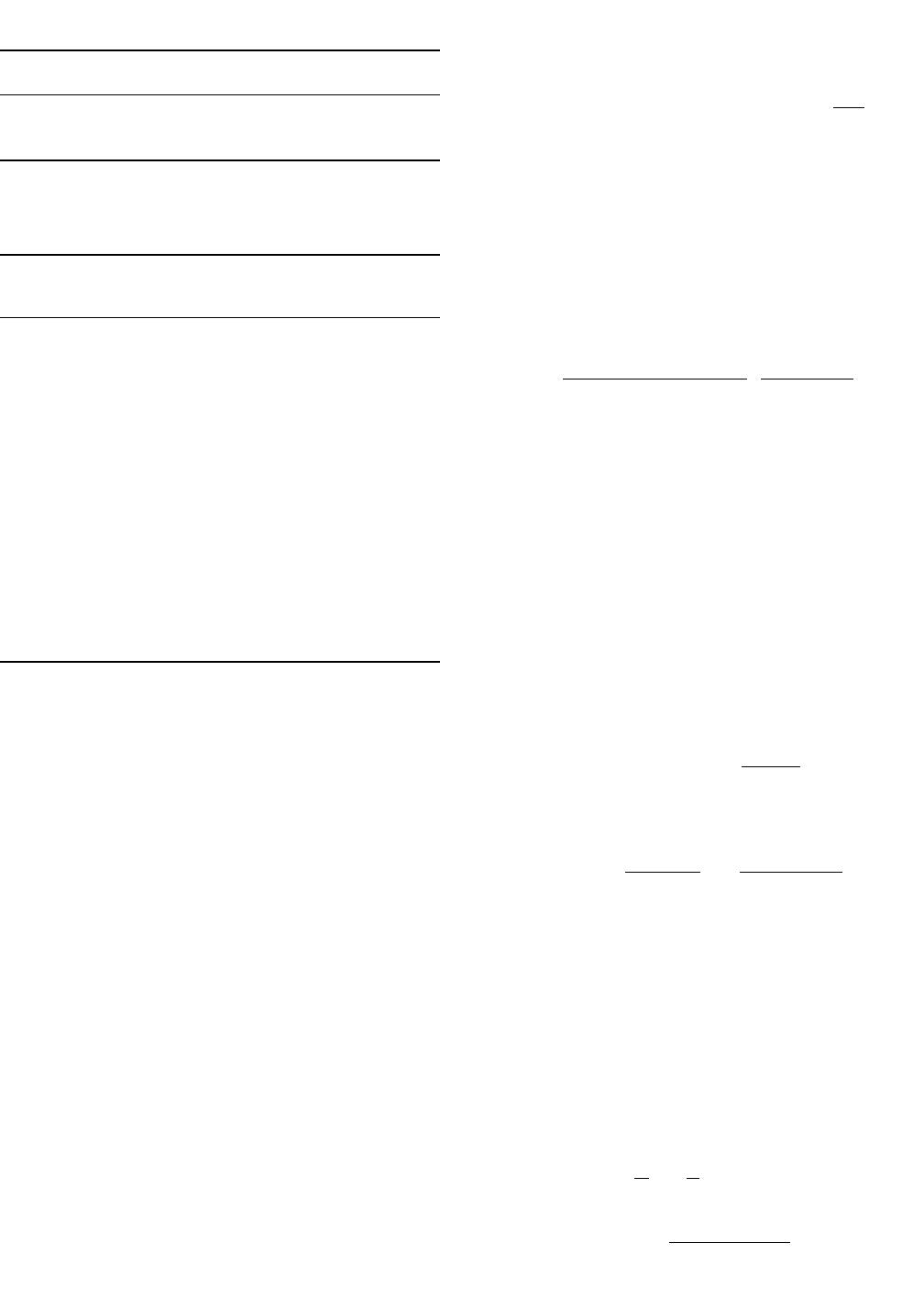

Fig. 7—Schematic concentration profile of elements in the slag and metal

phases near the interface: (a) silicon in the metal and FeO in the slag

based on mass transfer of silicon in the metal; and (b) silicon in the metal

and FeO in the slag based on simultaneous mass transfer of FeO in the

slag and silicon in the metal.

ms

mmL

r

SSSs

~!

r

m

m 5 [15]

0

s

mL

r

SSs

m

1 m

S

~!

r

m

For most desulfurizing slags (for instance, lime-rich slags),

the sulfur partition ratio L

S

is quite large, on the order of

10

2

to 10

4

. In those limiting cases, the overall mass transfer

coefficient for sulfur (m

0

) will reduce simply to the mass

transfer coefficient for sulfur in the metal ( ). Since FeO

m

m

S

in the slag was being reduced and silicon in the metal was

being oxidized, the concentration gradient of FeO and sil-

icon would affect the interfacial conditions for sulfur trans-

fer. Therefore, the coupled sulfur mass transfers in the slag

and metal were ruled out as the only two rate controlling

mechanisms.

D. Mass Transfer of FeO in the Slag

The mass transfer of FeO from the bulk slag to the in-

terface between the slag and metal was the next mechanism

considered. Because of the ionic nature of the slag, a more

accurate description of FeO transfer is the mass transfer of

Fe

2+

and O

22

ions. Since mass transfer will depend on the

slower of the two ions, namely, O

22

, it should be an ac-

ceptable assumption to consider the mass transfer of the

compound itself. A simplified way to conceptualize FeO

transfer is to look at a schematic of the concentration pro-

files of FeO in the slag and silicon in the metal, as shown

in Figure 6(b).

If the rate is controlled only by mass transfer of FeO in

the slag, the driving force for FeO reduction is proportional

to the difference between the concentration of FeO in the

bulk slag and the concentration of FeO at the interface

( ). The concentration of FeO at the interface is

ss,i

C 2 C

FeO FeO

in equilibrium with the silicon in the metal. This means that

for a constant silicon content, is a low, constant value

s, i

C

FeO

and is independent of the bulk FeO concentration. The ox-

ygen potential at the interface is defined by the equilibrium

between FeO at the interface and the iron in the metal.

Also, the sulfur partition ratio is inversely proportional to

the interfacial concentration of FeO. The sulfur partition

ratio would then be a constant value, independent of the

FeO content of the bulk slag. Based on the results of the

experiments, desulfurization behavior was dependent on the

bulk FeO content in the slag so mass transfer of FeO in the

slag was ruled out as the sole rate controlling step.

E. Mass Transfer of Silicon in the Metal

The mass transfer of silicon from the bulk slag to the

interface between the slag and metal is examined next. This

is shown schematically in Figure 7(a). If the mass transfer

of silicon in the metal is the sole rate controlling step, the

driving force for silicon oxidation is proportional to the

difference between the bulk and interfacial concentration of

silicon in the metal, ( ). The concentration of sil-

mm,i

C 2 C

Si Si

icon at the interface is a low and constant value and sets

the oxygen potential for desulfurization. In this case, the

sulfur partition ratio is inversely proportional to the inter-

facial concentration of silicon which is set by the equilib-

rium between the slag and the metal at the interface and

independent of the silicon content of the bulk metal. Based

on the experimental results, desulfurization is dependent on

the bulk silicon content of the metal, and mass transfer of

silicon in the metal is ruled out as the sole rate controlling

step.

F. Model Basis: Flux Equations

Sulfur transfer in the metal and slag, mass transfer of

FeO in the slag, and mass transfer of silicon in the metal

considered separately were eliminated as the individual rate

controlling steps for the reactions kinetics. Therefore, the

model is developed utilizing dynamic simultaneous mass

transfer of sulfur in the slag, sulfur in the metal, silicon in

the metal, and FeO in the slag. Based on the stoichiometry

for chemical Reactions [6] and [7], the balance of the mass

fluxes between silicon in the metal with FeO in the slag

and sulfur in the metal at any time during the process is

represented as

ms m

2 J 5 J 1 J [16]

Si FeO S

A schematic of the overall process of combined FeO and

silicon diffusion is shown in Figure 7(b).

These assumptions do not provide for a priori knowledge

of the dependency of the sulfur partition ratio, since the

interfacial concentrations of silicon in the metal and FeO

in the slag are in equilibrium and are no way related to the

bulk concentrations. The interfacial concentrations of sili-

con in the metal and FeO in the slag are related by the

equilibrium constant for chemical Reaction [7]. Therefore,

the mathematical model is based on the preceding flux

equations and the sulfur balance Eq. [14], which are solved

simultaneously at each time-step.

G. Mass Transfer Coefficients

Since the experiments were inductively stirred, the mass

transfer coefficient for sulfur and FeO in the slag and sulfur

and silicon in the metal can be related to one another based

on the relationship presented by Higbie.

[9]

1/2

4Dv

m 5 [17]

~!

p

r

METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS B VOLUME 28B, FEBRUARY 1997—53

Table IV. Diffusion Data for Sulfur and Silicon in Carbon

Saturated Iron at 1450 7C

Diffusing

Element

Concentration

(Wt Pct) D (cm

2

/s) Reference

S ,0.64 3.13 3 10

25

10

S — 3.09 3 10

25

11

Si — 2.20 3 10

25

11

Table V. Diffusion Data for Sulfur and Oxygen in Slags at

1450 7C

Diffusing

Element

Slag

Composition

(Wt Pct) D (cm

2

/s) Reference

40CaO

O

[17]

40SiO

2

6.17 3 10

2612

20Al

2

O

3

40CaO

O

[18]

40SiO

2

7.76 3 10

2612

20Al

2

O

3

38CaO

O 42SiO

2

7.5 3 10

2613

20Al

2

O

3

50.6CaO

S 39SiO

2

7.13 3 10

2714

10.4Al

2

O

3

40.8CaO

40.8SiO

2

S 51Al

2

O

3

6.65 3 10

2715

3FeO

0.4S

where

m 5 mass transfer coefficient (cm s

21

);

D 5 diffusivity (cm

2

s

21

);

v 5 surface velocity (cm s

21

); and

r 5 radius of the crucible (cm).

Diffusion data for sulfur and silicon in carbon saturated

iron and relevant components in example slags as presented

in the literature are summarized in Tables IV and V. Based

on average values obtained for the diffusivity of sulfur and

silicon in the metal as presented in Table IV and the ratios

of the square roots of the diffusivities, the relationship be-

tween the mass transfer for the elements in the metal phase

was taken to be

mm

m 5 1.2 m [18]

SSi

Likewise for the slag phases, the following relationship was

made based on the data presented in Table V:

ss

m 5 0.31 m [19]

SFeO

In the model, the values used for and were deter-

ms

mm

Si FeO

mined from the experimental data and were not derived

from first principles. The values for and were cal-

ms

mm

SS

culated from the input values for and by Eqs. [18]

ms

mm

Si FeO

and [19]. Therefore, the model only has two adjustable

mass transfer parameters, one for the slag and one for the

metal.

H. Governing Flux Equation

The governing dynamic mass transfer flux equation, an

expansion of Eq. [16], is represented as follows:

s

C

r

S m

m m m,i s s s,i m

2 m (C 2 C ) 5 m (C 2 C)

1

m (C 2 ) [20]

Si Si Si FeO FeO FeO 0 S

L

r

S s

Equation [20] is based on Eq. [16], which assumes silicon

is consumed by FeO reduction and the desulfurization re-

action.

I. Interfacial Concentration of FeO in the Slag

The interfacial concentration of FeO in the slag is defined

in terms of the interfacial concentration of silicon in the

metal using the equilibrium constant for chemical Reaction

[7] and is solved at each time-step.

2

2

aa

100 nMW

Fe SiO

s FeO

2

K 5 [21]

7

ii2 i,2

~!

f [pct Si]

g

(pct FeO) W

Si FeO s

where

a

Fe

5 activity of liquid iron;

5 activity of silica in the slag;a

SiO

2

5 activity coefficient of silicon in the metal at the

i

f

Si

slag/metal interface with respect to the 1 wt pct standard

state;

[pct Si]

i

5 interfacial silicon concentration in the metal

(wt pct);

(pct FeO)

i

5 interfacial FeO concentration in the slag

(wt pct);

g

FeO

5 activity coefficient for FeO in the slag

W

s

5 slag weight (g); and

n

s

5 number of moles in the slag.

The interfacial concentration of FeO in the slag can be

expressed as

1/2

1

i

(pct FeO) 5 G [22]

FeO

i

~!

[pct Si]

where

1/2

2

aa

100 nMW

Fe SiO

s FeO

2

G 5 [23]

FeO

i 2

~!~ !

f

g

KW

Si FeO 7 s

J. Oxygen Potential at the Slag Metal Interface

The interfacial oxygen potential is defined by the time-

dependent equilibrium between silica in the slag and silicon

in the metal. Because of the interfacial equilibrium condi-

tions between the constituents in chemical Reaction [7], the

oxygen potential defined by the equilibrium between silica

in the slag and silicon in the metal will be identical to the

oxygen potential defined by FeO in the slag and the liquid

iron. Therefore, the following reaction is at equilibrium at

the slag/metal interface:

Si 1 2O 5 (SiO ) [24]

2

The equilibrium constant of this reaction is

a

SiO

2

K 5 [25]

24

ii2

f [pct Si] (h )

Si O

54—VOLUME 28B, FEBRUARY 1997 METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS B

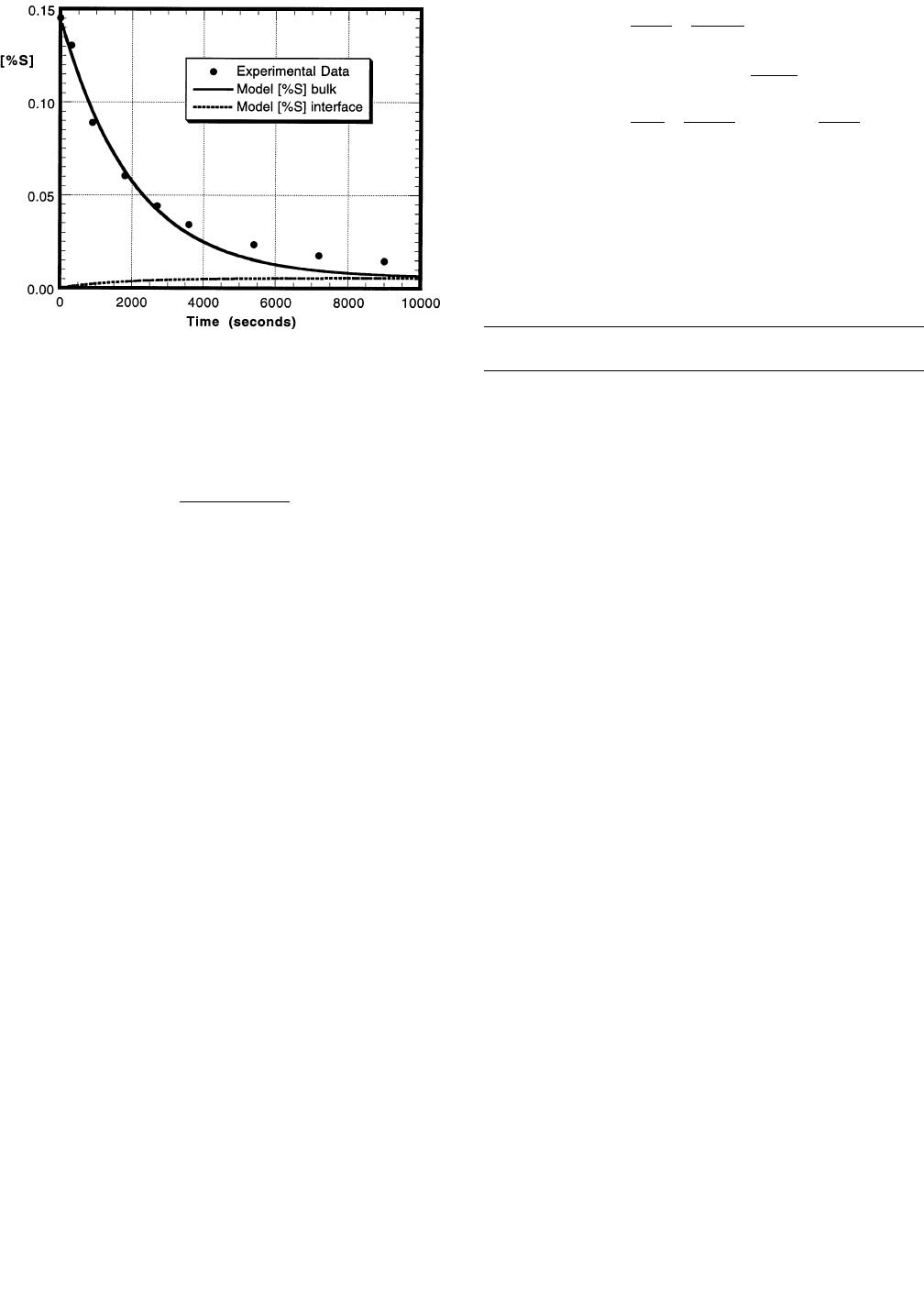

Fig. 8—Experimental data and model results for metal sulfur contents as

a function of time for experiment S5. Initial experimental conditions:

0.145 [pct S], 0.41 [pct Si], and 0 (pct FeO).

The oxygen potential at the slag/metal interface is defined

by

1/2

ii

f [pct Si] K

Si 24

h 5 [26]

O

~!

a

SiO

2

K. Sulfide Capacity of the Slag

Besides the oxygen potential of the system, the sulfide

capacity of the slag, C

S

, must be known to calculate the

sulfur partition ratio. In this model, the sulfide capacity

used is taken from the data originally generated by Ka-

lyanram et al. for a slag of similar composition to the one

used in the experiments.

[16]

Kalyanram et al. made meas-

urements at 1500 7C, so a temperature correction for the

temperature of the experiments used in this study (1450 7C)

was taken from work carried out by Nassaralla et al.

[17]

The

value used for the sulfide capacity in this study was 9.33

3 10

24

, which was found to be consistent with the average

sulfide capacities computed from the final experimental val-

ues for the experiments that were assumed to reach equi-

librium.

For example, in experiment S6, the sulfur partition ratio

calculated by mass balance of sulfur at the end of the ex-

periment was L

S

5 52.6. The final FeO content in the slag

equaled 0.13 pct FeO. The oxygen potential was based on

the final FeO content in the slag and the activity of liquid

iron in the metal. Based on Eq. [1], the sulfide capacity was

determined to be 9.4 3 10

24

. The value used for C

S

was

taken to be constant for the duration of the experiment since

the bulk slag composition did not appreciably change. For

the model, the sulfur partition ratio was calculated (Eq. [1])

based on the oxygen potential of the system and the sulfide

capacity of the slag, and the sulfur flux equation was

solved.

L. Interfacial Concentration of Silicon in the Metal

The overall flux equation which is solved at each time-

step is recast in terms of the interfacial concentration of

silicon in the metal:

s

m

r

MW

FeO s Si

i

[pct Si] 5 [pct Si] 2

m

~!~ !

MW 2 m

r

FeO Si m

1/2

1

(pct FeO) 2 G [27]

FeO

i

~~!!

[pct Si]

m

r

MW (pct S)

0 m Si

2 [pct S] 2

m

~!~ !~ !

MW 2 m

r

L

SSim S

As presented in Eq. [27], [pct Si]

i

is not a simple algebraic

expression and is solved by a numeric iteration technique.

The interfacial silicon content in the metal is solved and is

used as the basis for solving for the interfacial concentra-

tions of the FeO in the slag. These values are solved at

each time-step and then the flux equations

[9–12]

are solved.

A computer program was written in THINK Pascal for

the MACINTOSH* for this kinetic model. In this program,

*MACINTOSH is a trademark of Apple Computers, Inc., Cupertino,

CA.

the process variables of the system are read as input (tem-

perature, slag and metal weight, and composition). The only

other input variables in the program are the mass transfer

parameters for FeO in the slag and silicon in the metal. The

program output consists of the following bulk and interfa-

cial concentrations as a function of time: sulfur in slag,

sulfur in the metal, FeO in slag, and silicon in metal.

V. DISCUSSION

A. Kinetic Experiments

The mathematical model developed was utilized to ana-

lyze the results of the small scale experiments. In this anal-

ysis, the model is fit to the experimental results by

obtaining the ‘‘best-fit’’ values for the mass transfer coef-

ficients ( and ). The mass transfer coefficients used

ms

mm

Si FeO

in the model which best fit the experimental data are

m

m

Si

5 0.003 cm s

21

m

m

FeO

5 0.002 cm s

21

In experiments carried out in similar types of induction fur-

naces, the mass transfer coefficient is normally somewhat

larger than was observed in this study. This may be due to

the graphite ring consuming the bulk of the induction cou-

pling and the surface velocity at the interface between the

slag and metal not being as high as in the previous work

where no graphite ring was used. The importance of the

surface velocity at the slag/metal interface to determine the

mass transfer coefficient in an inductively stirred melt was

presented in Eq. [17]. Another contribution to this low mass

transfer coefficient as related to the velocity at the interface

of the slag and metal is the resistance that the slag provides

for flow. Also, it would be expected from the diffusivity

data that the value of would be about half of , and

sm

mm

FeO Si

this is about what was observed. Actually, was greater

s

m

FeO

than half of , and this could be attributed to the evolution

m

m

Si

of gas at the interface between the slag and the metal. This

is discussed later in detail.

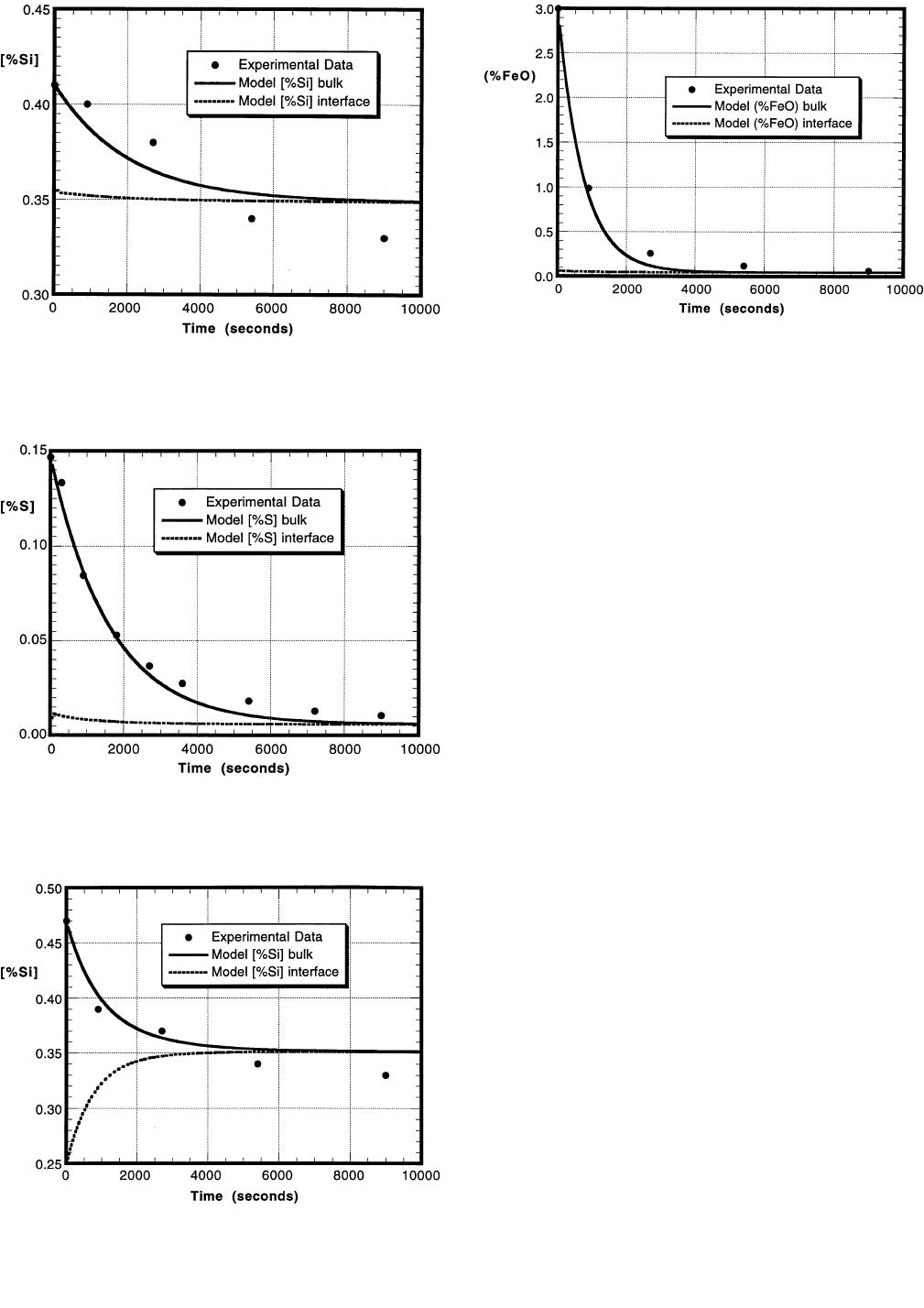

Figures 8 and 9 display the experimental results and the

kinetic model output for the sulfur and silicon contents in

the metal for experiment S5, where no FeO was added to

the slag. Since there was no FeO present in the slag, only

the desulfurization reaction (chemical Reaction [6]) was

METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS B VOLUME 28B, FEBRUARY 1997—55

Fig. 9—Experimental data and model results for metal silicon content as

a function of time for experiment S5. Initial experimental conditions:

0.145 [pct S], 0.41 [pct Si], and 0 (pct FeO).

Fig. 10—Experimental data and model results for metal sulfur content as

a function of time for experiment S7. Initial experimental conditions:

0.147 [pct S], 0.47 [pct Si], and 3 (pct FeO).

Fig. 11—Experimental data and model results for metal silicon content as

a function of time for experiment S7. Initial experimental conditions:

0.147 [pct S], 0.47 [pct Si], and 3 (pct FeO).

Fig. 12—Experimental data and model results for slag FeO content as a

function of time for experiment S7. Initial experimental conditions: 0.147

[pct S], 0.47 [pct Si], and 3 (pct FeO).

considered in this case, where the moles of silicon lost from

the metal is twice the moles of sulfur lost from the metal.

The agreement between the experimental data and the

model results is quite good for the sulfur profile but not as

good for the silicon. As seen from these figures, the inter-

facial (equilibrium) concentrations of sulfur and silicon are

plotted along with their respective bulk concentrations. It

can be seen that as the reaction proceeds, the bulk concen-

trations tend to the equilibrium concentrations, as expected.

There is a reasonable fit of the experimental results with

the calculated values obtained from the mathematical

model. Since this simplified case utilizes both the metal and

slag mass transfer coefficients, it can be assumed that the

values used for and are reasonable and should be

ms

mm

SS

used in the case where FeO is present in the slag. In the

experiments where FeO is present in the slag, it is difficult

to compare the model results with the experimental data

since the starting amount of FeO in the slag is not known

accurately. Experimentally, the FeO powder is added to the

master slag when it is at room temperature and mechani-

cally mixed. This ‘‘cold’’ slag is then introduced to the

metal melt which is at 1450 7C, and the starting time for

the desulfurization of the metal is defined as this point. The

problem inherent in this method is the fact that the slag

does not melt instantaneously as assumed. From visual in-

spection of the procession of the experiments, it takes a few

minutes for the slag to melt and cover the metal surface.

Figures 10 through 12 display the experimental data and

model predictions for the results of experiment S7, where

the initial cold amount of FeO in the slag is 3 pct and the

initial silicon content in the metal is 0.47 pct. Figure 10

shows the amount of sulfur in the metal as a function of

time as compared to the bulk concentration predicted from

the model. Also, the interfacial concentration of sulfur in

the metal is shown in this plot. Figure 11 displays the sil-

icon content in the metal vs time, and Figure 12 shows the

amount of FeO in the slag vs time. The model was run with

the initial amount of FeO in the slag as 3 pct. The plots

display that equilibrium is obtained near the end of the

experiment, about 8000 seconds after the slag is added to

the melt, when the bulk concentration profiles and interfa-

cial concentration profiles merge. The experimental data

56—VOLUME 28B, FEBRUARY 1997 METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS B

Fig. 13—Experimental results for CVPI experiments comparing the moles

of gas evolved for experiments where there was 0 or 5 pct FeO in the

slag.

and the model predictions fit reasonably well. Similar

agreement between the experimental results and model pre-

dictions were obtained with the other slag FeO contents and

metal silicon contents.

Based on the experimental data and the results obtained

from the model, the basis of the mathematical model seems

to be viable. The presence of FeO in the slag does affect

desulfurization of hot metal, and as the amount of FeO in

the slag increases, the desulfurization rate decreases and the

equilibrium sulfur content in the metal increases. Silicon in

the metal is stoichiometrically consumed by two reactions:

the desulfurization reaction and reduction of FeO from the

slag.

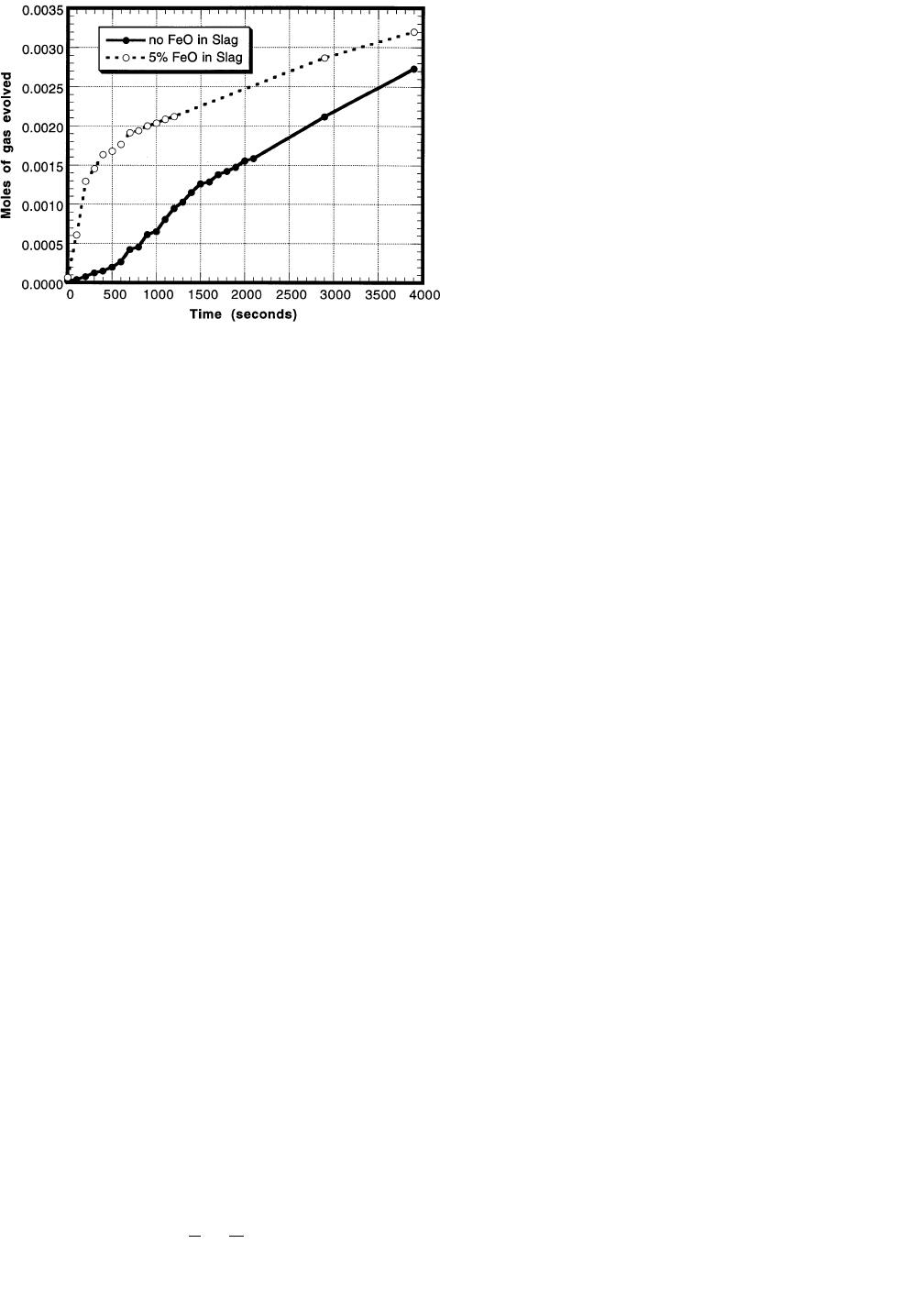

B. CVPI Experiments

Experiments were carried out to investigate if there was

any evolution of gas from reactions between the slag and

metal for the kinetic experiments. Based on the diffusivity

data presented, it is expected that the mass transfer coeffi-

cients for elements in the slag phase should be about half

of those in the metal phase for the case where there is a

stagnant slag metal interface. (The diffusivity of oxygen in

the slag is about a factor of 4 less than the diffusivity of

silicon in the metal, and they are related by the square root

of the diffusivity). Since it was found that the mass transfer

coefficients for the slag used in the kinetic model were

comparatively greater than expected, it was proposed that

there may be some evolution of gas at the interface between

the slag and metal that would increase the mixing in the

slag phase and promote better mass transfer kinetics.

Results from these experiments with 0 and 5 pct FeO in

the slag are presented in Figure 13 for metal initially con-

taining 0.17 pct silicon and 0.19 pct sulfur. The results

show that there is some gas evolution during the experi-

ments. It may be surprising that gas is produced in the

experiments, where FeO is not present in the slag, but it

has been found that the following chemical reaction may

take place at the slag/metal interface:

[7]

(SiO ) 1 2C 5 Si 1 2CO (g) [28]

2

Exit gas from some of these experiments was analyzed us-

ing a mass spectrometer (Dycor M100 Quadrupole Gas An-

alyzer), and it was found that the gas that evolved was

primarily CO with some CO

2

. The balance of the gas pro-

duced in the experiments where FeO was present in the

slag was assumed to be from the chemical reaction men-

tioned previously.

This amount of gas evolved was assumed to be enough

to provide for an increased mass transfer over the stagnant

case, but not a significant amount to account for it in the

mass balances for the model. The total amount of FeO that

is consumed by carbon in the metal (the difference of these

two plots) is determined to be about 5 pct of the total

amount of FeO in the slag that is reduced. This would sig-

nify that the bulk (95 pct) of the FeO is reduced by silicon

in the metal and would not significantly alter the mass bal-

ances assumed in the model.

For the experiment where no FeO was present in the slag,

about 0.0027 moles of CO (g) were produced throughout

the duration of the experiment. This amount of gas corre-

sponds to 0.00135 moles of silica that are reduced (Eq.

[28]), which equals about 7 pct of the total initial silicon

content in the metal. Therefore, the amount of silicon in

the metal available for desulfurization may actually be a

little higher than expected. There may also be experimental

reasons for measuring an increase in pressure in these ex-

periments that are independent of any reaction between the

slag and metal. These reasons include the initial heating

and melting of the slag and shifting of the reaction tube as

it was sealed. Like carbon reduction of FeO, it was assumed

that this 7 pct increase in the silicon content was insignif-

icant in the model mass balances.

A subsequent publication will include a scale up and ex-

pansion of this kinetic model to include desulfurization as

pertaining to the AISI Direct Steelmaking process. Also,

submerged injection of the desulfurizer will be incorporated

in the model to describe the industrial hot metal desulfur-

ization process.

VI. CONCLUSIONS

Experiments with carbon saturated iron containing sili-

con and sulfur and a slag of nominal composition 50 pct

CaO, 45 pct SiO2, and 5 pct MgO, with additions of FeO,

were carried out in this study. A mathematical kinetic

model was developed to predict sulfur, silicon, and FeO

transfer to describe the results of the laboratory experi-

ments. The results from the laboratory experiments and the

model show the following.

1. As FeO in the slag decreases, the desulfurization rate

increases and the final sulfur equilibrium content in the

metal is lowered. The oxygen potential at the interface

between the slag and metal is lower with lower FeO

contents in the slag, which increases the sulfur partition

ratio.

2. Greater desulfurization results as the amount of silicon

in the metal is increased. Higher contents of silicon in

the metal provide for a lower equilibrium FeO content

in the slag at the slag metal interface and a greater driv-

ing force for FeO reduction from the slag. This also

increases the sulfur partition ratio of the slag.