Vol.:(0123456789)

1 3

Journal of Neurology

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-020-10001-7

LETTER TOTHEEDITORS

Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome (PRES) inaCOVID‑19 patient

LuciaPrinciottaCariddi

1,5

· PayamTabaeeDamavandi

1,6

· FedericoCarimati

1

· PaolaBan

1

· AlessandroClemenzi

1

·

MargheritaMarelli

2

· AndreaGiorgianni

3

· GabrieleVinacci

4,5

· MarcoMauri

1,7

· MaurizioVersino

1,7

Received: 3 June 2020 / Revised: 13 June 2020 / Accepted: 16 June 2020

© Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature 2020

Abstract

Recently WHO has declared novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak a pandemic. Acute respiratory syndrome

seems to be the most common manifestation of COVID-19. Besides pneumonia, it has been demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2

infection affects multiple organs, including brain tissues, causing different neurological manifestations, especially acute

cerebrovascular disease (ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke), impaired consciousness and skeletal muscle injury. To our

knowledge, among neurological disorders associated with SARS-CoV2 infection, no Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy

Syndrome (PRES) has been described yet. Herein, we report a case of a 64-year old woman with COVID19 infection who

developed a PRES, and we suggest that it could be explained by the disruption of the blood brain barrier induced by the

cerebrovascular endothelial dysfunction caused by SARS-CoV-2.

Keywords Reversible encephalopathy syndrome PRES· COVID-19· Endothelialdysfunction

Abbreviations

COVID-19 Corona virus disease 19

CTA Computed tomography angiography

ED Endothelial dysfunction

SARS-Cov2 Severe acute respiratory syndrome covid 2

Case presentation

A 64-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital with a

10-day history of fever and dyspnea treated at home with

ceftriaxone.

Her medical history included hypertension, gastroesopha-

geal reflux disease, hyperuricemia, dyslipidemia, obstructive

sleep apnea and paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Her medica-

tions were: irbesartan/hydrochlorothiazide, acetylsalicylic

acid, pantoprazole, rosuvastatin, allopurinol and bisoprolol.

She was febrile (39°C) with marked dyspnea. Neurologi-

cal examination was unremarkable. Laboratory tests were

significant for lymphocytopenia with increased transami-

nases and LDH. Oxygen saturation was low, thereby oxygen

therapy was administered (Table1). Chest X-ray showed

reduction of the parenchymal transparency in basal region

of right lung.

A continuous positive airway pressure had to be started.

A nasopharyngeal swab resulted positive for SARS-CoV-2;

antiviral therapy with darunavir/cobicistat, associated with

hydroxychloroquine were started. After 24h, she was taken

to Intensive Care Unit: she was sedated and mechanical

ventilation was started. Antiviral plus antibiotic therapies

were continued for 10days. After 23days bronchial aspirate

turned negative for SARS-CoV-2.

On day 25 she woke up when sedation was weaned; she

was drowsy and complained of blurred vision. She showed

Lucia Princiotta Cariddi and Payam Tabaee Damavandi

contributed equally as first authors.

Marco Mauri and Maurizio Versino contributed equally as last

authors.

* Maurizio Versino

1

Neurology andStroke Unit, ASST Sette Laghi, Circolo

Hospital, Viale Borri, 57, 20100Varese, Italy

2

Pneumology Unit, ASST Sette Laghi, Circolo Hospital,

Varese, Italy

3

Neuroradiology Unit, ASST Sette Laghi, Circolo Hospital,

Varese, Italy

4

Radiology Unit, ASST Sette Laghi, Circolo Hospital, Varese,

Italy

5

Clinical andExperimental Medicine andMedical

Humanities, Center ofResearch inMedical Pharmacology,

University ofInsubria, Varese, Italy

6

University ofMilano Bicocca, Monza, Italy

7

University ofInsubria, Varese, Italy

Journal of Neurology

1 3

an altered mental status, a decreased left nasolabial fold, the

tone and the strength were slightly decreased in the legs, and

all deep tendon reflexes were reduced symmetrically. Brain

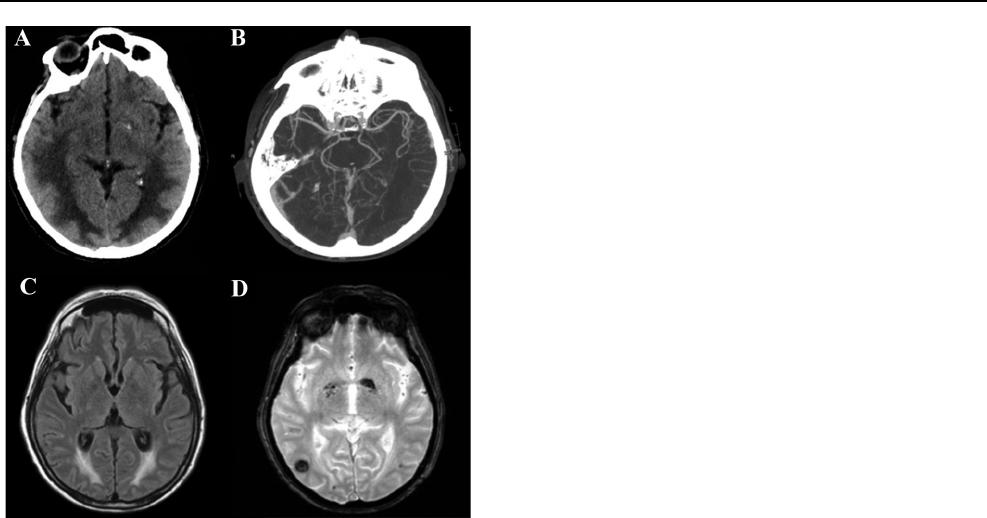

CT and CTA were consistent with hemorrhagic Posterior

Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome (PRES; Fig.1a, b).

In the following days spontaneous breathing was restored.

No epileptic seizures were reported during hospitalization.

On day 56 a brain MRI showed a reduction of the bilateral

edema with bilateral occipital foci of subacute hemorrhage

(Fig.1c, d). A second nasopharyngeal swab was negative for

SARS-CoV-2, and she was alert and fully oriented with a nor-

malization of blurred vision.

Table 1 Laboratory and

neurophysiologic assessment

Assessment Exams

Laboratory At admission in Emergency Department

Vital Signs: blood pressure—150/70mmHg, heart rate 90 beats per minute, respira-

tory rate was 22 breaths per minute, oxygen saturation: 88% in air room

Arterial blood gas: pH 7.48, pCO

2

27.9mmHg, pO

2

82.2mmHg, lactates

1.56mmol/L, CHCO

3

24.5mmol/L

Blood count: Red cells: 4.11 10

12

/L (4–5.5), Hemoglobin: 12.1g/dL (12–16.5),

White cells: 7.21 10

9

/L (4.3–11), Neutrophils: 84%, Lymphocytes: 12%, Mono-

cytes: 4%, Platelets: 180 10^9/L (150–450)

Reactive C protein: 245.5mg/L (0–5), Creatinine: 1.20mg/dL, AST: 83 U/L (11–34),

ALT: 87 U/L (8–41), LDH:481 U/L (125–220), Glucose: 122mg/dL (74–109)

Infectious diseases

Day 0:

Real-Time PCR oropharyngeal swab SARS-CoV-2: positive

Day 2:

Mycoplasma, Legionella, Chlamydia Pneumoniae Antibodies/antigen: negative;

Day 12:

Urine culture:positive (Candida Albicans > 100,000CFU/mL) treated with flucona-

zole

Day 16:

Blood cultures: positive (St. Epidermidis) treated with piperacilin/tazobactam and

daptomicyn

Day 23:

Bronchial aspirate RNA SARS-CoV-2: negative

Urine culture: negative

Day 26:

Bronchial aspirate RNA SARS-CoV-2: negative

Day 29:

Blood cultures: positive (St. Epidermidis)

Day 33:

Real-Time PCR oropharyngeal swab SARS-CoV-2: negative

Day 44:

Mycoplasma, Legionella, Chlamydia Pneumoniae Antibodies/antigen: negative

Day 47:

Blood culture: negative

Autoimmune assessment

ANA: positive 1:160 homogeneous pattern; ANCA, (PR3)-Anti-Neutrophil Cytoplas-

mic Antibodies, MPO neutrophil antigen: negative

Immunological assessment

Lymphocyte typing: 918 cells/uL ( 1.000–4.000), CD3% antigen: 62% (60–86), anti-

gen CD3 573 cells/uL ( 836–2644), CD4% antigen:23 (30–60), CD4 antigen: 213

clls/uL:493–1772, CD8% antigen: 38%(16–42), CD4/CD8: 0.6 (1.0–2.2), CD16/

CD56% antigen: 2 (3–24), CD19% antigen: 34 (5–22)

CSF of lumbar puncture

Clear, colorless, normal pressure, glucose: 139mg/dl, protein: 53mg/dl, cells: 0.8

mm

3

; Microscopic examination: negative for

HSV 1–2 DNA, VZV DNA, Mycobacterium, Borrelia-Antibodies, COVID19 tested

on CSF: negative

Thyroid function: 1.140 McUI/mL (0.270—4.200)

Neurophysiology EEG: globally slow activity, with focus on the central-temporal and posterior regions

EMG/ENG: bilateral compressive common peroneal nerve axonal neuropathy

Journal of Neurology

1 3

Discussion

PRES is characterized by acute impairment in level of con-

sciousness, headache, visual disturbances and seizures, with

cortical/subcortical vasogenic edema, involving predomi-

nantly the parietal and occipital regions bilaterally [1]. PRES

is commonly associated with blood pressure fluctuations,

renal failure, autoimmune conditions, sepsis, preeclampsia

or eclampsia and immunosuppressive-cytotoxic drugs. In

our patient the sepsis (Table1) was due to Staph. Epider-

midis, that has never been associated with PRES, and did

not induce a shock condition as is usually the case in septic

PRES [2–4]. None of the drugs given to our patient has been

associated with PRES [5].

Several studies suggested a key role of endothelial dys-

function (ED), combined with hemodynamic stress (hyper-

tensive crisis) and immunological activation with release of

cytokines (TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-1) able to activate endothelial

cells, thus increasing vascular permeability. ED is a prin-

cipal determinant of microvascular perfusion: by shifting

the vascular equilibrium towards a more pro-inflammatory,

pro-coagulant and proliferative state, it leads to ischaemia

and inflammation with edema [6].

This is the second report of hemorrhagic PRES in

COVID-19, and these other two patients were very similar

to ours.[7].

Mounting evidence suggests that the SARS-Cov2

directly infects endothelial cells causing diffuse inflamma-

tion [8–10]. The pivotal host cell receptor for the entry of

SARS-CoV-2 into the cells is the Angiotensin-Converting

Enzyme 2, which is also expressed by the brain endothe-

lium [9, 11]. Varga etal. [10] showed the presence of viral

elements within endothelial cells in different vascular beds,

suggesting a role of an ED in the systemic toxicity caused

by the virus.

In our patient we can rule out the causes of PRES listed

above. A contribution from the respiratory distress was

unlikely since PRES developed during mechanical ventila-

tion. We hypothesize that SARS-CoV-2 may have caused a

cerebrovascular ED which in turn was responsible for both

the hemorrhagic lesions and the for the disruption of the

blood brain barrier with vasogenic edema.

Availability ofdata andmaterial

Our data are available upon request to the corresponding

author.

Funding This research received no specific grant from any funding

agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflicts of interest The authors declare no potential conflicts of inter-

est with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this

article.

Consent for publication A written informed consent was obtained from

the patient.

Ethics approval Not applicable. This case has been described retro-

spectively, without the patient undergoing procedures and tests other

than those she already had to undergo to treat her clinical condition.

This research was performed in accordance with GCP and the ethical

standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki.

References

1. Hinchey J, Chaves C, Appignani B, Breen J, Pao L, Wang A, Pes-

sin MS, Lamy C, Mas JL, Caplan LR (1996) A reversible posterior

leukoencephalopathy syndrome. N Engl J Med 334(8):494–500.

https ://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM1 99602 22334 0803

2. Bartynski WS, Boardman JF, Zeigler ZR, Shadduck RK, Lister J

(2006) Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome in infection,

sepsis, and shock. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 27(10):2179–2190

3. Racchiusa S, Mormina E, Ax A, Musumeci O, Longo M, Granata

F (2019) Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES)

Fig.1 Radiological findings. a Brain axial CT on day 25 shows pos-

terior frontal and temporo-parieto-occipital symmetric bilateral

hypodensity of the subcortical white matter, and a tiny left occipi-

tal parenchymal hemorrhage. b Para-axial CTA scan confirms the

absence of vascular malformation and alterations of posterior circle

vessel caliber, suggestive of vasoconstriction mechanism. c Axial T2

Flair image on day 56 shows that vasogenic edema is reduced but still

detectable and d T2 Gradient-Echo reveals the onset of right temporal

hypodensity, correlated to hemorrhagic process

Journal of Neurology

1 3

and infection: a systematic review of the literature. Neurol Sci

40(5):915–922. https ://doi.org/10.1007/s1007 2-018-3651-4

4. Toledano M, Fugate JE (2017) Posterior reversible encephalopa-

thy in the intensive care unit. Handb Clin Neurol 141:467–483.

https ://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-63599 -0.00026 -0

5. Pilato F, Distefano M, Calandrelli R (2020) Posterior reversible

encephalopathy syndrome and reversible cerebral vasoconstriction

syndrome: clinical and radiological considerations. Front Neurol

11:34. https ://doi.org/10.3389/fneur .2020.00034

6. Fugate JE, Rabinstein AA (2015) Posterior reversible encepha-

lopathy syndrome: clinical and radiological manifestations, patho-

physiology, and outstanding questions. Lancet Neurol 14(9):914–

925. https ://doi.org/10.1016/S1474 -4422(15)00111 -8

7. Franceschi AM, Ahmed O, Giliberto L, Castillo M (2020) Hemor-

rhagic posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome as a mani-

festation of COVID-19 infection. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. https

://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A6595

8. Guo J, Huang Z, Lin L, Lv J (2020) Coronavirus disease 2019

(COVID-19) and cardiovascular disease: a viewpoint on the

potential influence of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/

angiotensin receptor blockers on onset and severity of severe acute

respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. J Am Heart Assoc

9(7):e016219. https ://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.120.01621 9

9. Sardu C, Gambardella J, Morelli MB, Wang X, Marfella R, San-

tulli G (2020) Hypertension, thrombosis, kidney failure, and

diabetes: is COVID-19 an endothelial disease? A comprehensive

evaluation of clinical and basic evidence. J Clin Med. https ://doi.

org/10.3390/jcm90 51417

10. Varga Z, Flammer AJ, Steiger P, Haberecker M, Andermatt R,

Zinkernagel AS, Mehra MR, Schuepbach RA, Ruschitzka F, Moch

H (2020) Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID-

19. Lancet 395(10234):1417–1418. https ://doi.org/10.1016/S0140

-6736(20)30937 -5

11. Natoli S, Oliveira V, Calabresi P, Maia LF, Pisani A (2020) Does

SARS-Cov-2 invade the brain? Translational lessons from animal

models. Eur J Neurol. https ://doi.org/10.1111/ene.14277