MichelJ. A. M.vanPutten

Dynamics

ofNeural

Networks

AMathematical and Clinical Approach

Dynamics of Neural Networks

Michel J. A. M. van Putten

Dynamics of Neural

Networks

A Mathematical and Clinical Approach

123

Michel J. A. M. van Putten

Clinical Neurophysiology Group

University of Twente

Enschede, The Netherlands

Neurocenter, Dept of Neurophysiology

Medisch Spectrum Twente

Enschede, The Netherlands

ISBN 978-3-662-61182-1 ISBN 978-3-662-61184-5 (eBook)

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-61184-5

© Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature 2020

This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part

of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations,

recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission

or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar

methodology now known or hereafter developed.

The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this

publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from

the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use.

The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this

book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the

authors or the editors give a warranty, expressed or implied, with respect to the material contained

herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. The publisher remains neutral with regard

to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This Springer imprint is published by the registered company Springer-Verlag GmbH, DE part of

Springer Nature.

The registered company address is: Heidelberger Platz 3, 14197 Berlin, Germany

Preface

This book evolved from the course “Dynamics of Neural Networks in Health and

Disease.” It treats essentials from neurophysiology (Hodgkin-Huxley equations,

synaptic transmission, prototype networks of neurons) and related mathematical

concepts (dimensionality reductions, equilibria, bifurcations, limit cycles, and phase

plane analysis). This is subsequently applied in a clinical context, focusing on EEG

generation, ischaemia, epilepsy, and neurostimulation.

The book is based on a graduate course taught by clinicians and mathematicians

at the Institute of Technical Medicine at the University of Twent e. Throughout the

text, we present examples of neurological disorders in relation to applied mathe-

matics to assist in disclosing various fundamental properties of the clinical reality at

hand. Exercises are provided at the end of each chapter; answers are included.

Basic knowledge of calculus, linear algebra, differential equations, and famil-

iarity with Matlab or Python is assumed. Also, students should have basic

knowledge about essentials of (clinical) neurophysiology, although most concepts

are shortly summarized in the first chapters. The audience includes advanced

undergraduate or graduate students in Biomedical Engineering, Technical

Medicine, and Biology. Applied mathematicians may find pleasure in learning

about the neurophysiology and clinical applications. In addition, clinicians with an

interest in dynamics of neural networks may find this book useful.

The chapter that treats the meanfield approach to the human EEG, Chap. 7, was

written by Dr. Rikkert Hindriks. The Chaps. 3 and 4, discussing essentials of

dynamics, were in part based on lecture notes by Prof. Stephan van Gils, Dr. Hil

Meijer, and Dr. Monica Frega made various useful suggestions to previous versions.

Further, Annemijn Jonkman, Bas-Jan Zandt, Sid Visser, Koen Dijkstra, Manu Kalia,

and Jelbrich Sieswerda are acknowledged for their critical reading and commenting

on earlier versions. Finally, I would like to thank our students and teaching assistants

who provided relevant feedback during the course.

Enschede, The Netherlands Michel J. A. M. van Putten

v

Prologue

A 64-year old, previously health y, patient was seen at the emergency department.

He woke up this morning with loss of muscle strength in his left arm and leg. On

neurological examination, he has a left-sided paralysis . A CT-scan of his brain

showed a hypodensity in the right middle cerebral artery area, with a minimal shift

of brain structures to the left, characteristic for a cerebral infarct (Fig. 1). His wife

tells you that he complained about some loss of muscle strength already the evening

before. He is admitted to the stroke unit. Two days later, he is comatose, with a

one-sided dilated pupil. A second CT-scan shows massive cerebral edema of the

right hemispher e with compression of the left hemisphere and beginning herniation.

The day after, he dies. What happened? Why did his brain swell? Which processes

are involved here? Could this scenario have been predicted and perhaps even

prevented?

A 34-year old woman is seen by a neurologist because of recurring episodes of

inability to “find the right words.” These episodes of dysphasia recur with a variable

duration and frequency, sometimes even several times per day. The duration is up to

several minutes, and recovery takes up to half an hour. She suffered from a trau-

matic brain injury half a year earlier and on her MRI scan a minor residual lesion

was shown near her left temporal lobe. Despite treatment with various anti-epileptic

drugs, she does not become seizure free. Early warning signs are essentially absent

and she finds it difficult to continue her job as a high school teache r. Why did her

How can a three-pound mass of jelly that you can hold in your palm imagine angels,

contemplate the meaning of infinity, and even question its own place in the cosmos?

Especially awe inspiring is the fact that any single brain, including yours, is made up of

atoms that were forged in the hearts of countless, far-flung stars billions of years ago. These

particles drifted for eons and light-years until gravity and change brought them together

here, now. These atoms now form a conglomerate—your brain—that can not only ponder

the very stars that gave its birth but can also think about its own ability to think and wonder

about its own ability to wonder. With the arrival of humans, it has been said, the universe

has suddenly become conscious of itself. This, truly, is the greatest mystery of all.

—V. S. Ramachandran, The Tell-Tale Brain: A Neuroscientist’s Quest for What Makes Us

Human

vii

seizures not respond to medication? Are there perhaps alternatives such as surgery

or deep brain stimulation? What triggers her seizures? Can we perhaps develop a

device that predicts her seizures?

A 72-year old man has recently been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. His

main complaint is a significant right-sided tremor and problems with walking, in

particular stopping and starting is difficult. Sometimes, it is even so severe that he

cannot move at all, a phenomenon called freezing. Initially, medication had a fairly

good effect on his tremor, with moderate effects on walking. The last years,

however, his tremor got worse, walking has almost become impossible, and his

symptoms show strong fluctuations during the day. Remarkably, cycling does not

pose any problems. What underlies this condition? Can we treat his tremor and

walking disability with other means than medication? And what causes the motor

symptoms in Parkinson’s disease in the first place?

A 23-year old university student was recently diagnosed with a severe mood

disorder. Her extremely happy weeks were alternated with depressive periods, and

she was eventually diagnosed wi th a manic-depressive disorder, with mood swings

occurring approximately every other two weeks. Treatment with medication had a

moderate effect on her mood with several side effects, including blunting of

emotion and loss of general interest. We all experience moderate changes in mood,

which is norm al. In this patient, however, these fluctuations are much stronger. Can

we better understand the underlying physiology? Could this unders tanding con-

tribute to prevention or better treatment? Are there alternatives for drug treatment,

for instance, deep brain stimulation?

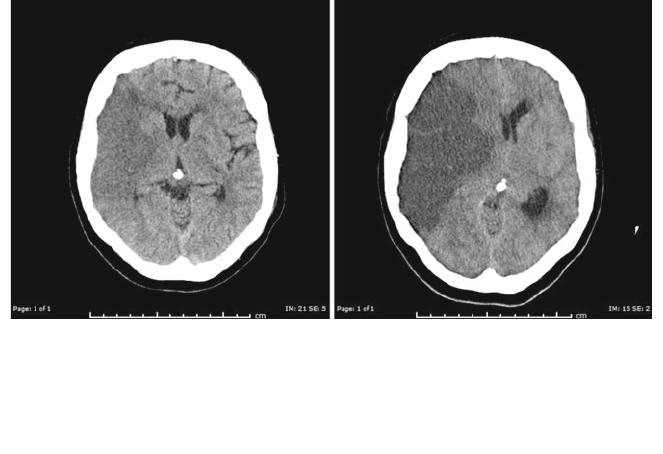

Fig. 1 Left: Noncontrast head CT of a patient with an acute right middle cerebral artery infarction,

showing hypodense gray and white matter on the right side of the brain. Note that this is left in the

image, as we “look from the feet upwards to the head” of the patient. Right: head CT two days

later shows an increase in the hypodensity and marked swelling of the infarcted tissue on the right,

with significant cerebral edema and brain herniations. Courtesy: M. Hazewinke l, radiologist

Medisch Spectrum Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands.

viii Prologue

We discuss neurophysiology and general principles for some of these neuro-

logical and neuropsychiatric diseases. Clinically relevant questions vary, but a

common element is a change in dynamics. Healthy brains switch from normal to

abnormal behavior, as in the transition to seizures. What are candidate mechanisms

that trigger seizures and why do some patients respond so poorly to current

anti-epileptic drugs? Initially, severe injury can suddenly become fatal, as in some

patients with stroke. Why do neurons swell in stroke patients and more so in some

and hardly in others? Motor behavior can be disturbed by the occurrence of tremors,

characterized by involuntary oscillations that are not present in a healthy motor

system. How should we treat tremors in patients with Parkinson’s disease? Why is

deep brain stimulation so effective in some? Moods oscillate between euphoria and

depression in patients with a manic-depressive disorder. In other patients, the

depressions are so severe that electroconvulsive therapy is the only treatment option

left. How does that work?

In the first two chapters, we treat essentials of neurophysiology: the neuron as an

excitable cell, action potentials, and synaptic transmission. Next to a treatment of the

phenomenology, we present a quantitative mathematical physiological context,

including the Hodgkin-Huxley equati ons. In Chaps. 3 and 4, we introduce scalar and

planar differential equations as essential tools to model physiologi cal and patho-

logical behavior of single neurons, This includes a treatment of equilibria, stability,

and bifurcations. In this chapter, we also discuss various reductions of the

Hodgkin-Huxley equations to two-dimensional models. Chapter 5 describes inter-

acting neurons. We review some fundamental “motifs,” treat the integrate-and-fire

neuron, and discuss synchronization. In Chap. 6, we introduce the basics of the

generation of the EEG, and show various clinical conditions where EEG recordings

are relevant. In Chap. 7, we discuss a meanfield model for the EEG, using the

physiological and mathematical concepts presented in earlier chapters. Two chapters

discuss pathology and include applications of the concepts and mathematical models

to clinical problems. Chapter 8 treats dynamics in ischemic stroke including a

detailed treatise of processes involved in edema/cell swelling. In Chap. 9, we discuss

clinical characteristics of epilepsy, the role of the EEG for diagnostics, and present

various mathematical model s in use to further understanding of (transition to) sei-

zures. Limitations of current treatment options and pharmacoresistance are treated, as

well. Finally, in Chap. 10, we review some clinical applications of neurostimulation.

All chapters contain examples and exercises; answers are included.

Mastering the contents of this book provides students with an in-depth under-

standing of general principles from physiology and dynamics in relation to common

neurological disorders. We hope that this enhances understanding of several

underlying processes to ultimately contribute to the development of better diag-

nostics and novel treatments.

Prologue ix

Contents

Part I Physiology of Neurons and Synapses

1 Electrophysiology of the Neuron

........................... 3

1.1 Introduction

...................................... 3

1.2 The Origin of the Membrane Potential

................... 4

1.2.1 Multiple Permeable Ions

....................... 7

1.2.2 Active Transport of Ions by Pumps

............... 9

1.2.3 ATP-Dependent Pumps

........................ 9

1.3 Neurons are Excitable Cells

........................... 10

1.3.1 Voltage-Gated Channels

....................... 10

1.3.2 The Action Potential

.......................... 11

1.3.3 Quantitative Dynamics of the Activation

and Inactivation Variables

...................... 13

1.3.4 The Hodgkin-Huxley Equations

................. 14

1.4 Voltage Clamp

.................................... 16

1.5 Patch Clamp

...................................... 19

1.5.1 Relation Between Single Ion Cha nnel Currents

and Macroscopic Currents

...................... 20

1.6 Summary

........................................ 22

Problems

............................................. 23

2 Synapses

............................................. 27

2.1 Introduction

...................................... 27

2.2 A Closer Look at Neurotransmitter Release

............... 29

2.3 Modeling Postsynaptic Currents

........................ 31

2.3.1 The Synaptic Conductance

..................... 32

2.3.2 Very Fast Rising Phase: s

1

s

2

................. 35

2.3.3 Equal Time Con stants: s

1

¼ s

2

.................. 35

2.4 Channelopathies

................................... 36

2.5 Synaptic Plasticity

.................................. 37

xi

2.5.1 Short Term Synaptic Plasticity .................. 37

2.5.2 Long-Term Synapti c Plasticity

.................. 39

2.6 Summary

........................................ 40

Problems ............................................. 41

Part II Dynamics

3 Dynamics in One-Dimension

.............................. 47

3.1 Introduction

...................................... 47

3.2 Differential Equations ............................... 50

3.2.1 Linear and Nonl inear Ordinary Differential

Equations

.................................. 50

3.2.2 Ordinary First-Order Differential Equations

......... 50

3.2.3 Solving First-Order Differential Equations

.......... 51

3.3 Geometric Reasoning, Equilibria and Stability

............. 55

3.4 Stability Analysis

.................................. 57

3.5 Bifurcations

...................................... 57

3.5.1 Saddle Node Bifurcation

....................... 58

3.5.2 Transcritical Bifurcation

....................... 62

3.5.3 Pitchfork Bifurcation

......................... 65

3.6 Bistability in Hodgkin-Huxley Axons

.................... 66

3.7 Summary

........................................ 67

Problems

............................................. 68

4 Dynamics in Two-Dimensional Systems

..................... 71

4.1 Introduction ...................................... 71

4.2 Linear Autonomous Differential Equations in the Plane

....... 72

4.2.1 Case 1: Two Distinct Real Eigenvalues

............ 73

4.2.2 Case 2: Complex Conjugate Eigenvalues

........... 75

4.2.3 Case 3: Repeated Eigenvalue

................... 76

4.2.4 Classification of Fixed Points

................... 76

4.2.5 Drawing Solutions in the Plane .................. 79

4.3 Nonlinear Autonomous Differential Equations in the Plane

.... 80

4.3.1 Stability Analysis for Nonlinear Systems

........... 82

4.4 Phase Plane Analysis

............................... 84

4.5 Periodic Orbits and Limit Cycles

....................... 87

4.6 Bifurcations

...................................... 89

4.6.1 Saddle Node Bifurcation

....................... 91

4.6.2 Supercritical Pitchfork Bifurcation

................ 92

4.6.3 Hopf Bifurcation

............................ 92

4.6.4 Oscillations in Biology

........................ 96

4.7 Reductions to Two-Dimensional Models

................. 97

4.7.1 Reduced Hodgkin-Huxley Model

................ 98

4.7.2 Morris-Lecar Model

.......................... 98

xii Contents