Huang

etal. acta neuropathol commun (2020) 8:219

https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-020-01092-4

RESEARCH

Eects ofH3.3G34V mutation ongenomic

H3K36 andH3K27 methylation patterns

inisogenic pediatric glioma cells

Tina Yi‑Ting Huang

1

, Andrea Piunti

2

, Jin Qi

1

, Marc Morgan

2

, Elizabeth Bartom

2

, Ali Shilatifard

2

and Amanda M. Saratsis

1,2,3*

Abstract

Histone H3.3 mutation (H3F3A) occurs in 50% of cortical pediatric high‑grade gliomas. This mutation replaces glycine

34 with arginine or valine (G34R/V), impairing SETD2 activity (H3K36‑specific trimethyltransferase). Consequently,

reduced H3K36me3 is observed on H3.3G34V nucleosomes relative to wild‑type, contributing to genomic instabil‑

ity and driving a distinct gene expression signature associated with tumorigenesis. However, it is not known if this

differential H3K36me3 enrichment is due to H3.3G34V mutant protein alone. Therefore, we set to elucidate the effect

of H3.3G34V mutant protein in pediatric glioma on H3K36me3, H3K27me3 and H3.3 enrichment in vitro. We found

that the doxycycline‑inducible shRNA knockdown of mutant H3F3A encoding the H3.3G34V protein resulted in loss

of H3.3G34V enrichment and increased H3K36me3 enrichment throughout the genome. After knockdown, H3.3G34V

enrichment was preserved at loci observed to have the greatest H3.3G34V and H3K36me3 enrichment prior to

knockdown. Induced expression of mutant H3.3G34V protein in vitro was insufficient to induce genomic H3K36me3

enrichment patterns observed in H3.3G34V mutant glioma cells. We also observed strong co‑enrichment of H3.3G34V

and wild‑type H3.3 protein, as well as greater H3K27me3 enrichment, in cells expressing H3.3G34V. Taken together,

our study demonstrates the effects of H3.3G34V mutant protein on genomic H3K36me3, H3K27me3 and H3.3 enrich‑

ment patterns in isogenic cell lines.

Keywords: Pediatric high‑grade glioma, Post‑translational modifications, H3K36me3, Histone H3 mutations

© The Author(s) 2020. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing,

adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and

the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material

in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material

is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds

the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://crea‑

tivecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdo‑

main/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Introduction

Pediatric high-grade glioma (pHGG) is the number one

cause of cancer death in children, with a 5-year survival

of less than 20%. is dismal prognosis is in large part

due to an historical lack of understanding of its distinct

biology and the presumption that pHGG is biologically

identical to its adult counterpart, resulting in ineffective

treatment. However, with the development of next-gen

-

eration sequencing technologies to analyze rare tumor

specimens, knowledge of pHGG biology significantly

increased over the past decade. Somatic missense muta

-

tions in genes encoding Histone H3 isoforms, including

H3F3A, HIST1H3B and HIST1H3C, were subsequently

identified in up to 50% of supratentorial hemispheric

pHGG, and 80% of pediatric diffuse midline gliomas

(DMG), a form of pHGG in the thalamus or brainstem

[11, 15, 20]. ese mutations are associated with distinct

tumor biology and poorer clinical outcome, and are now

understood to play a role in pediatric gliomagenesis. As a

result, determining the effects of these mutations on his

-

tone H3 function and regulation of gene transcription, in

order to identify more effective therapeutic targets, is of

great interest.

Open Access

*Correspondence: [email protected]g

3

Division of Pediatric Neurosurgery, Department of Surgery, Ann &

Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, 225 E Chicago Avenue,

Box 28, Chicago, IL 60611‑2991, USA

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article

Page 2 of 13

Huangetal. acta neuropathol commun (2020) 8:219

In hemispheric pHGG, somatic mutations of H3F3A

(GGG to GTG) result in a glycine 34 to arginine (G34R)

or valine (G34V) substitution on the histone H3.3 N-ter

-

minal tail, while H3F3A mutations in DMG result in

lysine to methionine alterations (K27M or K36M). Sev

-

eral studies have focused on the effects of these muta-

tions on global methylation, chromatin structure, and

transcription regulation to promote tumorigenesis. For

example, mutant H3.3K27M protein exhibits higher

affinity for EZH2, a H3K27-specific lysine methyltrans

-

ferase, compared to wildtype H3.3, resulting in EZH2

sequestration and preventing PRC2 from propagating

transcriptionally repressive H3K27 methylation [14].

Mutant H3.3K36M protein inhibits H3K36-specific

lysine methyltransferases, including NSD1, NSD2, and

SETD2, reducing global H3K36 methylation [3, 12, 21].

In contrast, less is known about the epigenetic and tumo

-

rigenic effects of H3.3G34V/R mutations in pHGG. Sev-

eral studies comparing H3.3G34V mutant and wild type

cell lines suggest distinct epigenetic changes at H3K27

and H3K36 in association with H3.3G34V/R mutation,

as well as alteration to DNA repair pathways leading

to transcriptional upregulation, increased mutational

burden and genomic instability [2, 10, 16]. However, as

these studies did not use isogenic cell lines, the distinct

mechanism by which H3.3G34V/R mutation exerts the

observed changes is not clear. erefore, we set to better

elucidate the direct epigenetic effects of H3.3G34V muta

-

tion in pediatric glioma invitro using isogenic cell lines.

Here, we demonstrate changes in genomic enrichment of

multiple chromatin marks after DOX-inducible knock

-

down of H3F3A in an H3.3G34V mutant pediatric glioma

cell line, and H3.3G34V mutation transduction in wild-

type astrocytes, providing insight on epigenetic effects of

this mutation that promote tumorigenesis.

Materials andmethods

Cell lines andculture conditions

Experiments were conducted using an established

H3.3G34V mutant patient-derived pediatric high-grade

glioma cell line (KNS42), and Histone H3.3 wild-type

human astrocytes (NHAs, ScienCell #1800). KNS42 was

obtained from Rintaro Hashizume (Northwestern Uni

-

versity), it is well characterized as previously described

[6]. KNS42 cells were maintained in EMEM (10009CV,

Corning) with 5% FBS (16000-044, Gibco). NHA cells

were maintained in high glucose DMEM (11995-065,

Gibco) and 10% FBS, according to the cell line provider’s

recommendation. Cells were grown in an incubator with

5% CO

2

at 37 °C. All experiments were conducted in

accordance to institutional protocols and approvals (NU

IRB# STU00202063).

H3.3G34V mutation induction andknock‑down

Lentiviral delivery of a doxycycline-inducible RNAi

vector targeted against H3F3A was transduced to

KNS42 cells to knock down H3.3G34V protein expres

-

sion. e vector contains the selectable markers of

puromycin as well as a red fluorescent protein (RFP)

reporter. Lentiviral vector-mediated doxycycline-

inducible cDNA encoding a c.104G > T p.(Gly34Val)

H3F3A mutation was transduced to NHAs in order to

express H3.3G34V mutant protein. is vector, pUC57-

Kan, contained a kanamycin resistant gene. A vector

containing doxycycline-inducible H3F3A for wild-type

H3.3 protein expression was used as negative control.

All vectors were purchased from Genscript. A total of

250,000 cells from each cell line were transduced with

lentivirus for 6h, rinsed in PBS, then cultured in their

respective media as described above. A second round of

lentiviral transduction was performed 24h later. After

an additional 24h, antibiotics were added at 2µg/mL.

Cells were then cultured in their respective media for

three to 5days to achieve desired confluency. For dox

-

ycycline-induced transduction conditions, doxycycline

was added at 1:5000 every other day for 1week (days

one, three, five, seven), and on day eight cells were col

-

lected as a pellet for Western Blotting to confirm pro-

tein expressions, or crosslinked with 1% formaldehyde

for ChIP-Seq (see below). Cells without doxycycline

treatments were cultured and collected in parallel. Flu

-

orescent imaging and flow cytometry were performed

to select for cells with successful protein knockdown or

transduced expression.

Western blotting

Protein was extracted from cells using RIPA buffer

(89900, ermo Fisher Scientific). A total of 60 µg of

protein (from whole cell extract) was separated by elec

-

trophoresis in a 4–15% precast protein gel (4561086, Bio-

Rad) and transferred to PVDF membranes. Blocking was

subsequently performed with 5% non-fat milk in TBST,

followed by incubation with anti-H3K27Ac antibody at

1:500 dilution (8173S, Cell Signaling Technology) over

-

night. After 5 washes with TBST, membranes were incu-

bated with HRP-conjugated anti-Rabbit IgG antibody at

1:1000 (7074 Cell Signaling Technology) for 1h. Pierce

ECL Plus (32132, ermo Fisher Scientific) was used to

detect protein bands. Blots were then stripped (46430,

ermo Fisher Scientific) and re-probed with anti-total

H3 primary antibody at 1:1000 dilution (14269S, Cell

Signaling Technology) as a loading control. HRP-con

-

jugated anti-Mouse IgG antibody (7076, Cell Signaling

Technology) was used to detect total H3 signal. Densi

-

tometry analysis was performed with image J.

Page 3 of 13

Huangetal. acta neuropathol commun (2020) 8:219

Cell proliferation assay

Cell proliferation was measured by counting viable cells

using the TC20 Automated Cell Counter (Bio-Rad).

3 × 10

5

cells were seeded in cell culture dishes. At 3 and

7 days after seeding, cells were harvested, dissociated

into single cell suspension, and stained with 0.4% Trypan

Blue Solution (15250061, ermoFisher) for 5min before

counting.

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was assessed using the CellTiter-Glo Lumi-

nescent Assay (G7570, Promega). 3000 cells were seeded

in 96-well plate. Measurements were taken 1, 3, 5, and 7

days after seeding. Reagent was diluted at 1:1 ratio with

PBS to achieve optimal luminescent range. 100µL rea

-

gent was added to cells in 100µL media. e mix was

incubated for 10min at room temperature with gentle

shaking, followed by luminescent measurement.

Cell crosslinking andchromatin immunoprecipitation

For each immunoprecipitation, 30 million cells were

crosslinked using freshly prepared 1% formaldehyde in

complete cell medium for 10min at RT, and subsequently

quenched with 0.125M glycine for 5min. e cells were

then rinsed twice in cold PBS, gently scraped from the

plates and centrifuged in a 15mL tube (Falcon) at 1350×g

for 8min at 4 °C. Crosslinked cells were either stored

in − 80 °C or used immediately for chromatin immu

-

noprecipitation, as previously described [14]. Briefly,

crosslinked cells were resuspended in 10mL buffer 1 for

10min at 4°C then centrifuged at 1350×g for 5min at

4°C. Pellet was resuspended in 10mL buffer 2 for 10min

at RT then centrifuged at 1350×g for 5min at 4°C. Pellet

was resuspended 1mL buffer 3 and transferred to a 1mL

milliTUBE (520135, Covaris). Sonication was performed

using the Covaris E220 ultrasonicator with the following

parameters: 20% duty cycle, 175 PIP, 200 cycles/burst,

for 8 min. After sonication, sample was centrifuged at

20,000×g for 15min at 4°C and supernatant containing

chromatin was collected. 50 µL of chromain were de-

crosslinked with elution buffer for 3h at 65°C and DNA

was extracted using PCR purification kit (28104, Qiagen).

Purified DNA were loaded in a 1.5% agarose gel to check

for the fragment size (average range 200–500bp). A total

of 100µL ChIP dilution buffer was added to the remain

-

ing sheared chromatin. A total of 10µL of each sample

was saved at 4°C to serve as input. e remaining chro

-

matin was incubated with primary antibody on a nutator

overnight at 4°C (refer to Table1 for a list and dilution of

antibodies used). e following day, 60µL of 50% protein

A/G agarose beads (sc-2003, Santa Cruz Biotech) were

added to the samples and incubated for 3h on a nutator

at 4°C. Agarose beads were pelleted by centrifugation at

2500×g for 1min and washed with 1mL of RIPA buffer

four times followed by 1mL of 50mM NaCl in TE. e

beads and the 10µL input sample were resuspended in

200µL elution buffer for 30min at 65°C then centrifuged

for 2min at 15,000×g. Supernatant was transferred into a

new 1.6mL tube and de-crosslinked overnight 65°C. e

following day, DNA was extracted with PCR purification

kit (28104, Qiagen), and eluted to a final volume of 60µL.

A total of 45µL of each sample and input were used for

library preparation and subsequent sequencing steps. All

additional reagents (Elution buffers 1, 2, 3, Elution buffer,

10× ChIP dilution buffer, RIPA buffer, and elution buffer)

were prepared as previously described [14].

Library Preparation andNext‑Generation Sequencing

ChIP-Seq libraries were prepared with the KAPA Library

preparation kit (KK8234, Kapa Biosystems) and NETflex

DNA barcodes (514104, Bioo Scientific). A total of 10µg

DNA was used as starting material for input and immu

-

noprecipitation samples. Libraries were amplified with a

thermocycler for 13 cycles. Post-amplification libraries

were size-selected at 250-45bp in length using the Agen

-

court AMPure XP beads (A63881, Beckman Coulter).

Libraries were validated using the Agilent High Sensi

-

tivity DNA Analysis Kit (5067-4626). ChIP-Seq libraries

were single-read sequenced on the Illumina NextSeq500

Sequencing System.

ChIP‑Seq data analysis

Reads were filtered using the FASTX-Toolkit suite and

read quality was assessed with FastQC v0.11.5. After

removal of duplicated reads, unique reads were mapped

to human reference genome Hg38. ChIP-Seq reads were

aligned with the ENCODE pipeline. Peaks were called

with MACS2 v2.1.0 software with cutoff of p < 0.01.

Enrichment values were determined as log2(Normalized

experimental read count—normalized input read count)

Table 1 List ofantibodies used

*We would like the table to be inserted following the section “Cell Crosslinking

and Chromatin Immunoprecipitation” of Materials and Methods

Antibody Company Catalog # ChIP WB

H3.3WT Millipore 09‑838 10 µg 1:1000

K36me3 Homemade na 30 µL 1:1000

G34V RevMAb 31‑1193‑00 10 µg 1:1000

K27me3 Homemade na 30 µL na

Total H3 CST 14,269 na 1:1000

Anti‑Rabbit IgG, HRP CST 7074 na 1:5000

Anti‑Mouse IgG, HRP CST 7076 na 1:5000

Page 4 of 13

Huangetal. acta neuropathol commun (2020) 8:219

in regions of interest in each ChIP specimen and cor-

responding input sample. Called peaks were annotated

with HOMER v4.10 to the nearest gene. Active enhanc

-

ers were defined as H3K27ac peaks excluded from the

transcription start site (TSS) (2.5kb upstream and down

-

stream). ChIP-Seq reads density and data visualizations

were generated using Deeptools v3.1.1. Additional func

-

tional pathways and upstream regulator analysis was

performed on differentially enriched loci using Ingenuity

Pathways Analysis software (Qiagen, Germantown MD).

Results

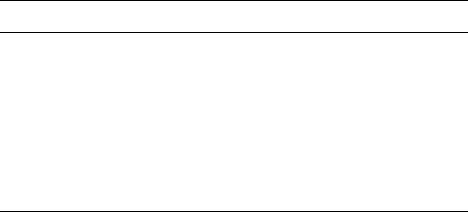

Lentiviral induced knockdown andexpression ofH3.3G34V

To characterize the epigenetic effects of H3.3G34V

mutant protein in pediatric glioma, we compared global

methylation and Histone H3 enrichment patterns in

isogenic cell lines. We used doxycycline-induced lenti

-

viral delivery of genetic constructs designed to silence

(shRNA) or express (cDNA) mutant and wild-type

H3F3A in H3.3G34V mutant glioma cells (KNS42),

and H3 wild type astrocytes (NHA). Using fluorescent

imaging, we measured lentiviral RFP expression after

DOX-induction to confirm vector expression (Fig. 1a).

Western blot analysis of whole-cell extracts confirmed

successful knockdown of H3.3G34V mutant protein in

glioma cells treated with doxycycline, compared to those

not treated with doxycycline and those transduced with

H3F3A for wild-type H3.3 expression, with no significant

reduction in H3K36 trimethylation across conditions

(Fig.1b). In turn, we observed DOX-induced expression

of H3.3G34V mutant protein in cDNA transduced astro

-

cytes, with no mutant protein detected in untreated cells,

or in cells transduced with H3F3A (Fig. 1c). While we

achieved significant overexpression of H3.3G34V mutant

protein in astrocytes compared to control, the maxi

-

mum level of mutant protein we could express in astro-

cytes is only 28.9% of the level observed in H3.3G34V

mutant glioma KNS42 (Additional file 1: Figure S1A,

B). Flow cytometry was used to select the top 30% cells

with successful H3.3G34V knockdown and knock-in, for

subsequent ChIP-Seq (Fig.1d). We did not observe sig

-

nificant difference in cell viability (Additional file1: Fig-

ure S1C) or proliferation (Additional file1: Figure S1D, E)

between KNS42 with and without doxycycline-induced

H3.3G34 knockdown, nor between NHA overexpressed

with H3.3G34V and H3.3 control. On ChIP-Seq analysis,

we observed decreased H3.3G34V enrichment at H3F3A

in KNS42 glioma cells after DOX-induced transduc

-

tion of H3F3A shRNA, relative to KNS42 cells that were

transduced without DOX induction, or not transduced

(Fig. 1e). We also confirmed enrichment of H3.3G34V

mutant protein at H3F3A in DOX-induced astrocytes,

with no mutant protein in untreated NHAs or those

transduced with wild-type H3F3A cDNA (Fig.1e). Out

-

side of H3F3A, metagene plots of H3.3G34V enrichment

within the gene body for the top 1000 most H3.3G34V-

enriched genes demonstrated reduction, but not com

-

plete elimination, of H3.3G34V deposition in KNS42

with DOX-induced knockdown compared to KNS42

cells that were transduced but without DOX induction.

Higher H3.3G34V enrichment is also observed in NHAs

transduced for H3.3G34V expression, compared to

NHAs with only wild-type H3.3 expression (Fig.1f).

H3.3G34V Co‑enriches withWild‑type H3.3

Overall, we observed greater H3.3 enrichment in cells

expressing H3.3G34V mutant protein. Specifically, we

identified 270,656 wild-type H3.3 peaks in glioma cells

after H3.3G34V knockdown (6628 promoter, 144,735

gene body), and significantly fewer H3.3 peaks in KNS42

glioma cells with intact H3.3G34V expression (164,785

total, 4071 promoter, 87,770 gene body, Fig. 2a). e

same trend was observed in astrocytes induced to

express H3.3G34V (77,018 total peaks, 2019 promoter,

40,530 gene body) compared to controls (15,9235 total

peaks, 3952 promoter, 84,746 in gene body, Fig.2a). At

genes previously reported to have greater WT H3.3

enrichment in H3,3G34V mutant tumors compared to

WT, manipulation of H3.3G34V mutant protein expres

-

sion had no effect on WT H3.3 enrichment (Fig.2b). To

further determine the effect of H3.3G34V expression on

genomic enrichment of WT and mutant H3.3, we identi

-

fied the top 10,000 loci most-enriched for H3.3G34V in

transduced KNS42 cells without DOX induction (nega

-

tive control), and compared H3.3G34V and WT H3.3

enrichment at these loci across experimental conditions.

Fig. 1 Genetic Modification of Histone H3.3 expression in Pediatric Glioma Cells and Astrocytes. a Expression of RFP reporter was confirmed in

> 95% of Doxycycline‑induced cells. b H3.3G34V expression was significantly reduced in lentiviral‑transduced KNS42 cells treated with Doxycycline,

compared to no Doxycycline and control conditions. **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001. c H3.3G34V protein was expressed in lentiviral‑transduced NHAs

treated with doxycycline, with no H3.3G34V expression observed in controls. d Flow cytometry was used to select the top 30% cells with H3.3G34V

knockdown and knock‑in for subsequent ChIP‑Seq analysis. e Genome browser view of H3.3G34V enrichment at the H3F3A locus across cell lines

studied. Tracks highlighted in red are those conditions without H3.3G34V expression. f Metagene profile of H3.3G34V enrichment in the gene body

across the top 1000 most H3.3G34V‑enriched genes in KNS42. Reduction of H3.3G34V enrichment is observed following doxycycline‑induced

knockdown (light blue versus navy blue lines). Greater H3.3G34V enrichment is also observed in NHA transduced for H3.3G34V expression (green

line) compared to control transduced for H3.3WT expression (orange line)

(See figure on next page.)

Page 5 of 13

Huangetal. acta neuropathol commun (2020) 8:219

a

b c

d

e

f

Page 6 of 13

Huangetal. acta neuropathol commun (2020) 8:219

a

b

c

d

e

Fig. 2 H3.3G34V Co‑enriches With Wild‑type H3.3. a Relative proportion of H3.3WT enrichment across gene elements with H3.3G34V expression

or knock‑down. b H3.3 enrichment at SOX2 was greatest KNS42 cell s expressing H3.3G34V, compared to NHAs lacking H3.3G34V expression (red

highlight) or after H3.3G34V transduction. c, d Co‑enrichment of H3.3G34V and H3.3WT was observed across experimental conditions at the top

10,000 loci most‑enriched for C) H3.3G34V, and D) H3.3WT in transduced KNS42 cells without DOX induction. e When the top 10,000 loci most

enriched for H3.3G34V, H3.3 wild‑type, H3K36me3 and H3K27me3 in transduced KNS42 cells without DOX induction are compared, greatest overlap

is observed between H3.3G34V and wild‑type H3.3 enrichments patterns, with 3041 common loci between these two groups

Page 7 of 13

Huangetal. acta neuropathol commun (2020) 8:219

We detected co-enrichment of H3.3G34V and WT H3.3

in all glioma cell treatment conditions at these 10,000 loci

most enriched for H3.3G34V (Fig.2c), as well as at the

10,000 loci most enriched for WT H3.3 (Fig.2d). When

these loci are mapped to the nearest gene, H3.3G34V and

WT H3.3 enriched loci have the most overlap, with 3041

shared loci between groups (Fig. 2e). Taken together,

these data suggest that glioma H3.3G34V expression is

associated with increased WT H3.3 enrichment through

-

out the genome, that WT H3.3 and H3.3G34V strongly

co-enrich, and that loci most enriched by these proteins

do not significantly change with H3.3G34V knockdown.

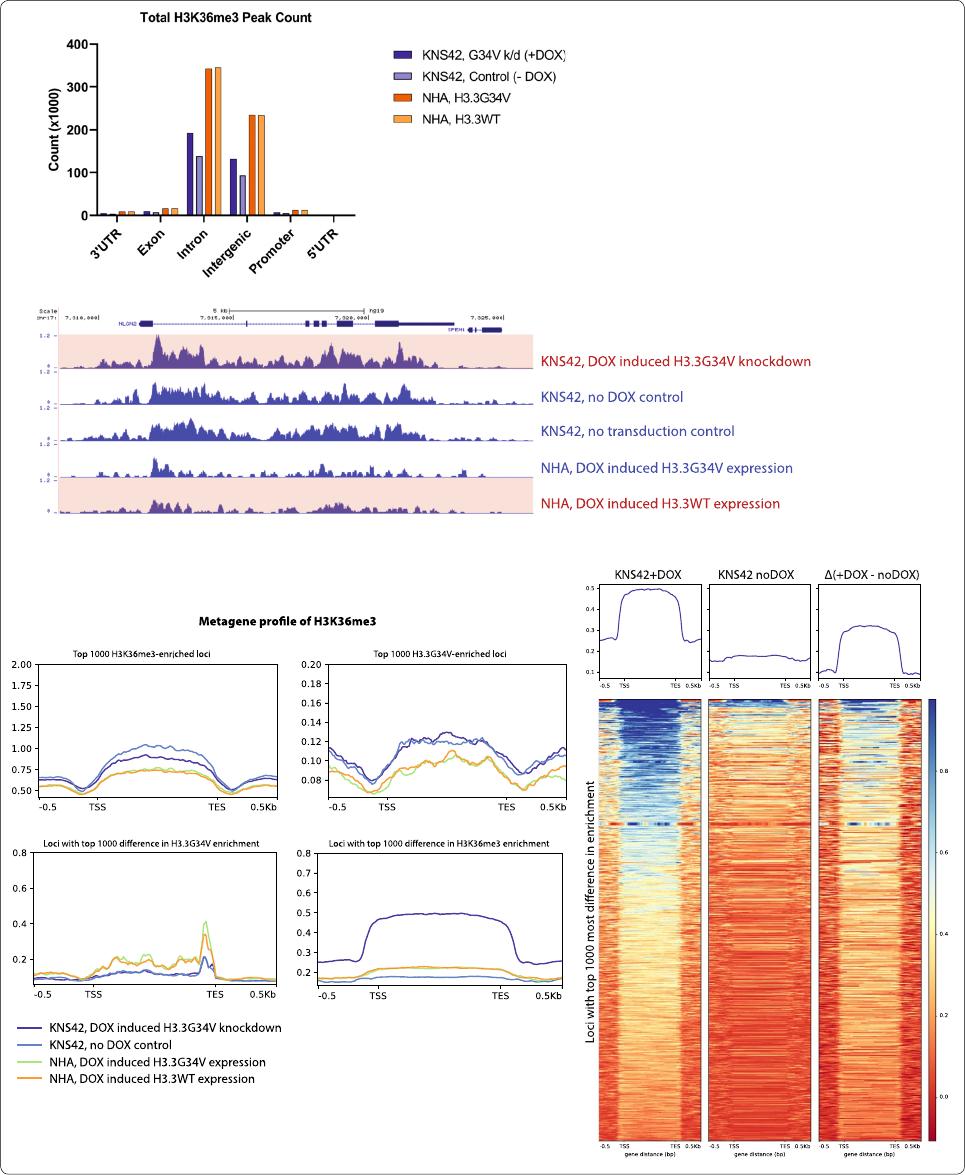

H3.3G34V does notaect global H3K36me3 enrichment

levels

Next, we set to determine the effects of H3.3G34V expres-

sion on patterns of genomic H3K36me3 enrichment.

Consistent with previous studies [17], H3.3G34V knock

-

down in glioma cells did not result in significant change in

the level of global H3K36me3 enrichment across all gene

elements evaluated, with a total of 354,857 K36me3 peaks

after H3.3G34V knockdown (7187 promoter, 202,284

gene body), compared to 254,315 H3K36me3 peaks cells

in KNS42 cells with intact H3.3G34V expression (5193

promoter, 145,856 gene body, Fig.3a). Similarly, we did

not observe a significant difference in the number of

H3K36me3 peaks in astrocytes after H3.3G34V knock-in

compared to WT cells (Fig.3a).

In H3.3G34V mutant KNS42 cells, we observed no

difference in H3K36me3 enrichment with or without

DOX-induced H3.3G34V knockdown, at neither the

1000 most H3K36me3 enriched loci, nor at the 1000

most H3.3G34V enriched loci (Fig. 3c, top left and

top right panels). Additionally, we not observe any dif

-

ference in H3K36me3 enrichment in NHAs, with or

without induced H3.3G34V expression. It is possible

that H3.3G34V knockdown in KNS42 did not occur

at loci with highest H3.3G34V enrichment, nor at

loci with highest H3K36me3 enrichment. To test this

hypothesis, we examined the loci with highest differ

-

ence in H3.3G34V and H3K36me3 enrichment, with

and without DOX-induced H3.3G34V knockdown. At

the 1000 loci with the greatest difference in H3.3G34V

enrichment between no DOX and DOX-induced

H3.3G34V knockdown conditions, we also saw no dif

-

ference in H3K36me3 enrichment (Fig.3c, bottom left

panel). Interestingly, at the 1000 loci with the greatest

difference in H3K36me3 enrichment with versus with

-

out H3.3G34V knockdown, we observed much greater

H3K36me3 enrichment with H3.3G34V knockdown

compared to no DOX control (Fig. 3c, bottom right

panel). For example, we saw reduced enrichment with

H3K36me3 at neuroligin-2, NLGN2 with H3.3G34V

knockdown, compared to transduced KNS42 with no

DOX control and KNS42 non-transduced cell lines

(Fig.3b). ese data are consistent with previous obser

-

vations that H3.3G34V mutation leads to local reduc-

tions in H3K36me3 enrichment. Additionally, our data

indicate that the loci with differences in H3K36me3

enrichment after H3.3G34V knockdown are neither

those with greatest H3.3G34V enrichment, nor those

with the greatest H3K36me3 enrichment.

In contrast, induced expression of H3.3G34V was not

sufficient to change genomic H3K36me3 enrichment

patterns. Evaluation of the top 1000 loci with the most

significantly different H3K36me3 enrichment between

no DOX and DOX-induced knockdown of H3.3G34V

in KNS42 showed that, compared to no DOX control,

KNS42 cells with DOX-induced H3.3G34V knock

-

down have greater overall H3K36me3 enrichment at

698 loci (Fig.3d). It has been previously suggested that

H3.3G34V expression leads to differential distribu

-

tion of H3K36me3 on approximately 150 genes [19].

Taken together, our data suggest that DOX-induced

H3.3G34V knockdown does not affect the most

H3.3G34V or H3K36me3 enriched loci, but does have

specific genomic effects on a limited subset of biologi

-

cally relevant genes.

Fig. 3 G34V mutation does not affect global H3K36me3. Increased H3K36me3 is observed at loci with G34V knockdown. a Relative proportion of

H3K36me3 enrichment across gene elements with H3.3G34V expression or knock‑down. b H3K36me3 enrichment at the NLGN2 gene is higher in

KNS42 after G34V knockdown, compared to KNS42 no DOX control and non‑transduced KNS42. However, transduced H3.3G34V into NHAs had

no effect on H3K36me3 enrichment patterns. c Metagene profile of H3K36me3 enrichment. No significant difference in H3K36me3 enrichment

was observed at the 1000 most H3K36me3 enriched loci (top left), nor at the 1000 most H3.3G34V enriched loci (top right) with or without

DOX‑induced H3.3G34V knockdown. No difference H3K36me3 enrichment was also observed at the 1000 loci with the greatest difference in

H3.3G34V enrichment between KNS42 no DOX and DOX‑induced H3.3G34V knockdown (bottom left). In contrast, greater H3K36me3 enrichment

was observed in 1000 loci with the greatest difference in H3K36me3 enrichment with H3.3G34V knockdown, compared to no DOX control (bottom

right). d Heatmap profiles of K36me3 peaks at loci with the top 1000 most difference in enrichment before and after knockdown. Signals from (left)

KNS42 with DOX‑induced G34V knockdown, (middle) KNS42 without G34V knockdown (no DOX control), and (left) the difference between them (Δ,

left minus middle). Positive values indicate that KNS42 with DOX‑induced G34V knockdown has higher K36me3 enrichment compared to no DOX

control

(See figure on next page.)

Page 8 of 13

Huangetal. acta neuropathol commun (2020) 8:219

a

b

c

d

Page 9 of 13

Huangetal. acta neuropathol commun (2020) 8:219

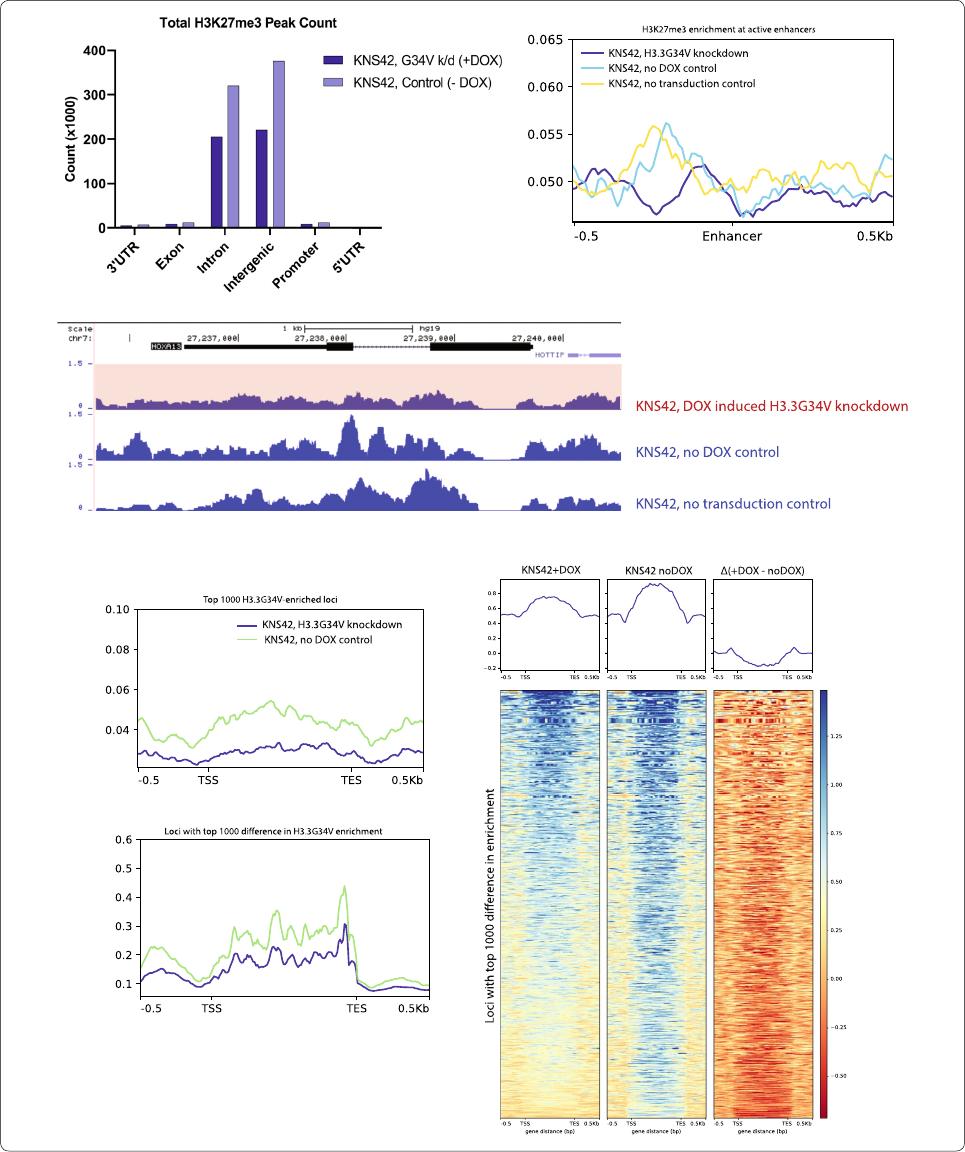

H3.3G34V isassociated withhigher H3K27me3 enrichment

Several studies have shown that H3.3G34V directly

impacts the modification state of adjacent K27 and K36

residues on the mutant H3.3 protein [2]. In line with this,

we observed greater H3K27me3 enrichment in KNS42

cells with H3.3G34V (740,497 peaks total, 11,516 pro

-

moter, 332,437 gene body), compared to KNS42 cells after

H3.3G34V knockdown (457,844 peaks total, 8270 pro

-

moter, 214,405 gene body) (Fig.4a). e greater enrich-

ment of H3.3K27me3 in non-transduced KNS42 and

transduced KNS42 with no DOX control compared to

KNS42 cells with DOX-induced H3.3G34V knockdown

was observed at active enhancers (Fig. 4b). In turn, at

HOXA13 we saw lower enrichment of H3K27me3 in

KNS42 cells with DOX-induced H3.3G34V knockdown,

compared to transduced KNS42 with no DOX control and

non-transduced KNS42, indicating that the H3.3G34V

mutation is associated with higher H3K27me3 enrich

-

ment (Fig.4c). Indeed, at the top 1000 most H3.3G34V-

enriched loci in KNS42 without DOX, we observed that

KNS42 cells without DOX-induced H3.3G34V knock

-

down harbored higher HK27me3 enrichment relative

to other cell lines studied (Fig.4d, top panel). is same

finding was observed at loci with greatest differential

H3.3G34V enrichment between DOX-induced H3.3G34V

knockdown cells and no-DOX controls (Fig. 4d, bot

-

tom panel). Heatmap profiles of the top 1000 most

H3K27me3 enriched loci in KNS42 showed that DOX-

induced knockdown of H3.3G34V results in lower relative

H3K27me3 enrichment, compared to no DOX controls.

H3.3G34V enrichment implicates distinct molecular

pathways

As H3.3G34V mutation is associated with distinct

changes in H3K36me3 and H3K27me3 enrichment pat

-

terns, we sought to determine functional pathways of

gene expression implicated by differential enrichment

patterns of mutant and wild-type H3.3. Functional path

-

ways analysis revealed cellular assembly and organiza-

tion (p = 1.12 × 10

−3

), cellular function and maintenance

(p = 1.18 × 10

−3

), and cell signaling (p = 8.81 × 10

−5

) as

the top molecular functions associated with the gene set

co-enriched in H3.3G34V and H3K36me3. Cell death

and survival (p = 1.12 × 10

−2

), cellular development

(p = 1.25 × 10

−4

), and cellular function and maintenance

(p = 1.25 × 10

−4

), are the top molecular and cellular func-

tions implicated by the gene set co-enriched in H3.3G34V

and K27me3. As expected, the top disease associated

with both these gene sets was cancer (p = 2.11 × 10

−10

).

GO and KEGG analyses were also performed to iden

-

tify functional annotations of genes with the most differ-

ential H3.3G34V, H3.3WT, and H3K36me3 enrichment

between KNS42 with intact H3.3G34V expression and

H3.3G34V knockdown. Cellular metabolism and onco

-

genesis were consistently the top two enriched pathways

in cells expressing H3.3G34V (Additional file 2: Figure

S2), with metabolic pathways implicated as the top cellu

-

lar function of this gene set (−log(p value) = 12.92–21.15,

Additional file3 Figure S3). Cellular neuron projection

morphogenesis and neuron differentiation were also

highly enriched in this gene set, consistent with previous

studies showing genes enriched in H3K36me3 contribute

to in neuronal differentiation and cell proliferation [19].

Discussion

Somatic missense mutations that alter histone H3.3 struc-

ture and function are uniquely common in pediatric

high-grade glioma. Tumors harboring the H3.3G34V/R

mutation are clinically and biologically distinct from wild

type tumors, with poorer progression free and overall

survival, and unique genomic, proteomic, methylomics

and epigenetic profiles relative to wild-type tumors [5,

9]. However, the mechanisms by which these mutations

lead to tumorigenesis are still not completely understood.

While prior studies have attempted to compare the effects

of H3.3G34V invitro, these studies did not employ iso

-

genic cell lines. Here, we genetically modified pediatric

glioma cells and normal astrocytes using a DOX-induci

-

ble construct in order to more accurately determine the

effects of H3.3G34V expression on the glioma epigenetic

landscape that may contribute to tumorigenesis.

Prior studies have shown that unlike the K27 and K36

amino acid residues on the histone H3 N-terminal tail,

the H3G34 residue is not post-translationally modified.

(See figure on next page.)

Fig. 4 H3.3G34V is associated with higher H3K27me3 enrichment. a Relative proportion of H3K27me3 enrichment across gene elements

with H3.3G34V expression or knock‑down in KNS42 cells. b Metagene profile of H3K27me3 enrichment at active enhancers (H3K27ac peaks

2.5 kb away from TSS). Higher H3K27me3 was observed in transduced KNS42 without DOX and non‑transduced KNS42 compared to KNS42

with G34V knockdown. c At HOXA13, H3K27me3 enrichment is lower in KNS42 with G34V knockdown, compared to KNS42 no dox control and

non‑transduced KNS42. Blue tracks are cell lines that harbor, or overexpressed, H3.3G34V; red tracks are cell lines that do not harbor, or knockdown,

H3.3G34V. d Metagene profile of H3K27me3 enrichment. H3K27me3 enrichment in the gene body across the top 1000 (top) most G34V‑enriched

genes in KNS42 TRIP no dox control. (bottom) most diff genes in G34V enrichment before and after KD in KNS42 TIRP ± DOX. e Heatmap profiles of

K27me3 peaks at the top 1000 most K27me3 enriched loci. Signals from (left) KNS42 with DOX‑induced G34V knockdown, (middle) KNS42 without

G34V knockdown (no DOX control), and (left) the difference between them (Δ, left minus middle). Negative values in the third column indicate that

KNS42 with DOX‑induced G34V knockdown has lower K27me3 enrichment compared to no DOX control

Page 10 of 13

Huangetal. acta neuropathol commun (2020) 8:219

However, H3G34 does lie in close proximity to H3K36,

which undergoes methylation during transcriptional

elongation. As a result, H3.3G34V/R mutations may

alter accessibility of H3K36 to lysine methyltrans

-

ferases, thereby affecting H3K36 methylation and hence

gene expression. For example, a recent study reported

a

c

d e

b