Structure and Viscosity of Molten CaO-SiO

2

-Fe

x

O

Slag During the Early Period of Basic Oxygen

Steelmaking

RUI ZHANG, YU WANG, XUAN ZHAO, JIXIAN G JIA, CHENGJUN LIU, and YI MIN

According to the composition variation during the initial period of basic oxygen steelmaking,

ice-quenched samples of the CaO-SiO

2

-Fe

x

O system were prepared, and the viscosity and

structure of molten slag were further analyzed by a rotary viscometer and Raman spectroscopy,

respectively. The results showed that Si

4+

existed as Q

0

,Q

1

,Q

2

and Q

3

units. The O

2

ions led

to the depolymerization of [SiO

4

] tetrahedrons from Q

3

to Q

0

units with increasing Ca/Fe ratio.

For Fe

3+

cations, two types of [FeO

4

] tetrahedron and [FeO

6

] octahedron coexisted in the

molten slag, and coordination of Fe

3+

transformed from tetrahedron to octahedron with the

Ca/Fe ratio increasing to 3.18. Viscosity of molten slag showed a continuous decrease because

of the simpler network. Moreover, to clarify the viscosity-structure relationship, the viscos ity

estimation equation applied to the CaO-SiO

2

-Fe

x

O-based system was established in terms of the

deconvolution result of the melt structure.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11663-020-01888-8

The Minerals, Metals & Materials Society and ASM International 2020

I. INTRODUCTION

BASIC oxygen steelmaking is widely used in the

primary smelting process of steel because of the better

smelting effect and the shorter smelting cycle. The core

task of basic oxygen steelmaking is to control the

appropriate chemical composition and temperature of

molten steel by desiliconization, dephosphorization and

decarburization. However, the different smelting periods

have different functions during basic oxygen steelmak-

ing. The main task of the initial smelting period is to

promote the dephosphorization reaction by rapid slag-

ging. At this period, molten slag plays an irreplaceable

metallurgical role in fixing phosphorus transferred from

molten steel and controlling the slag-steel reaction rate.

These metallurgical functions are closel y related to the

viscosity of the converter slag. The suitable viscous flow

of molten slag can facilitate the chemical reaction to

eliminate impurity elements and control the heat trans-

fer, mass transfer and smelting stability related to the

active multiphase reaction among molten slag, liqui d

steel and gas.

[1,2]

To adjust the viscosity of molten slag, the relationship

of the viscosity-structure-composition of converter slag

was investigated in previous studies,

[3–7]

which showed

that the increasing CaO/SiO

2

ratio and MgO resulted in

lower viscosity of the converter slag because of a

decrease in the complex structures of the [SiO

4

] tetra-

hedron. The structural role of MgO is similar to that of

CaO, which could cut off the bridging oxygen of the

[SiO

4

] tetrahedron. Therefore, investigations on the

structures of molten slag are essential to gain a thorough

comprehension of the viscosity of metallurgical slag

systems.

Considering the structure of the converter slag, the

structural behaviors of silicon as a network-forming ion

are explicit, and it can form the tetrahedral unit by

combining oxygen to construct a three-dimensional

network structure.

[8]

The structural behaviors of alkali

and alkaline earth metals in converter slag are also clear.

For example, as typical network modifiers, calcia and

magnesia can dissociate into Ca

2+

,Mg

2+

and O

2 [9]

The dissociated O

2

can cut off the bridging oxygen

bonds of the network structure, forming two non-bridg-

ing oxygen bonds. The dissociated Ca

2+

and Mg

2+

,

called compensator cations, play a role in compensating

the electronegativity of complex anion groups such as

RUI ZHANG, YU WANG, XUAN ZHAO, and CHENGJUN

LIU are with the Key Laboratory for Ecological Metallurgy of

Multimetallic Ores (Ministry of Education), Shenyang 110819,

Liaoning, P.R. China, and also with the School of Metallurgy,

Northeastern University, Shenyang 110819, Liaoning, P.R. China.

JIXIANG JIA is with the State Key Laboratory of Metal Material for

Marine Equipment and Application, Anshan 114021, Liaoning, P.R.

China. YI MIN is with the Key Laboratory for Ecological Metallurgy

of Multimetallic Ores (Ministry of Education), Shenyang 110819,

Liaoning, P.R. China, and also with the School of Metallurgy,

Northeastern University, Shenyang 110819, Liaoning, P.R. China, and

also with the Key Laboratory for Ecological Metallurgy of

Multimetallic Ores (Ministry of Education), Shenyang 110819,

Manuscript submitted July 31, 2019.

METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS B

the SiO

4

unit to maintain the electrical neutrality of the

network. However, other important components of

converter slag have more complicated struc tural behav-

iors. For example, the valence values of iron ions are not

fixed. Even though the valence values of iron ions are

identical, different structural types are formed by iron

ions. Mysen

[10]

and Virgo

[11]

thought that Fe

3+

cations

behaved as network formers as well as network mod-

ifiers and Fe

2+

cations only existed as network modifiers

in the SiO

2

-Al

2

O

3

-Fe

2

O

3

-based slag. Zhang et al.

[12]

also

reported that the larger concentration of Fe

3+

cations

resulted in the coexis tence of a [FeO

4

] tetrahedron and

[FeO

6

] octahedron. In addition, some studies

[13,14]

revealed that Fe

2+

cations were chiefly regarded as

network formers in the K

2

O-FeO-SiO

2

systems, and

only when divalent cations were absent would a few

ferrous ions fill the larger gaps caused by ferrous ions

because of Fe

3+

merging into the sites of silicate

tetrahedrons. Consequently, there is no consensus on

the structures of converter slag containing Fe

2+

and

Fe

3+

. Particularly research on the evolution of struc-

tural units of Fe

3+

in converter slag is relatively lacking.

Currently, although the initial period of basic oxygen

steelmaking is considered the fundamental stage of

acquiring satisfactory liquid steel, the slagging process in

this stage has not been paid attention yet. In the present

work, focusing on the evolution of the slag composition

during the initial period of the basic oxygen steelmaking

process, the viscosity and structure of the simplified

CaO-SiO

2

-Fe

x

O slag system are examined, which can

reveal the viscosity transition from the perspective of the

melt structure. Moreover, the quantitative relationship

between the viscosity and melt structure is established in

terms of the deconvolution results of Raman spectra.

The results contribute to understanding the macroscopic

properties and control metallurgical behavior of con-

verter slag and thereby provide theoretical guidance for

designing the slagging route for basic oxygen

steelmaking.

II. EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

A. Design of Converter Slag

For traditional basic oxygen steelmaking, composi-

tions of converter slag mainly consist of CaO, SiO

2

and

Fe

x

O, with a small amount of MgO, MnO and P

2

O

5

.

Considering the chemical property and structural role,

MgO is similar to CaO and MnO is similar to FeO.

[15]

The influence of P

2

O

5

on the melt structure is not

considered because there is relatively less content in the

molten slag. As a result, the CaO-SiO

2

-Fe

x

O ternary

system is designed as the experimental slag system in

present study.

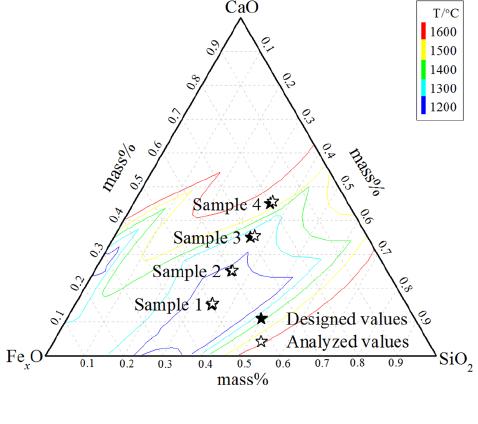

During the initial smelting period, silicon and iron

elements in the converter slag are preferentia lly oxidized

to silica and iron ox ide. Then, the generated silica and

iron oxide could penetrate into the interior slag layer

along the capillary of lime (the main component of lime

is CaO), promoting the melting of lime. In this reaction

process, the CaO content increases from 17 to 32

mass pct, the FeO content decreases from 30 to 15

mass pct, the total iron content also decreases from 28

to 17 mass pct, and SiO

2

content stabilizes ne ar 20

mass pct.

[16,17]

Referring to these data, the specific

composition of the designed slag is plotted in Figure 1.

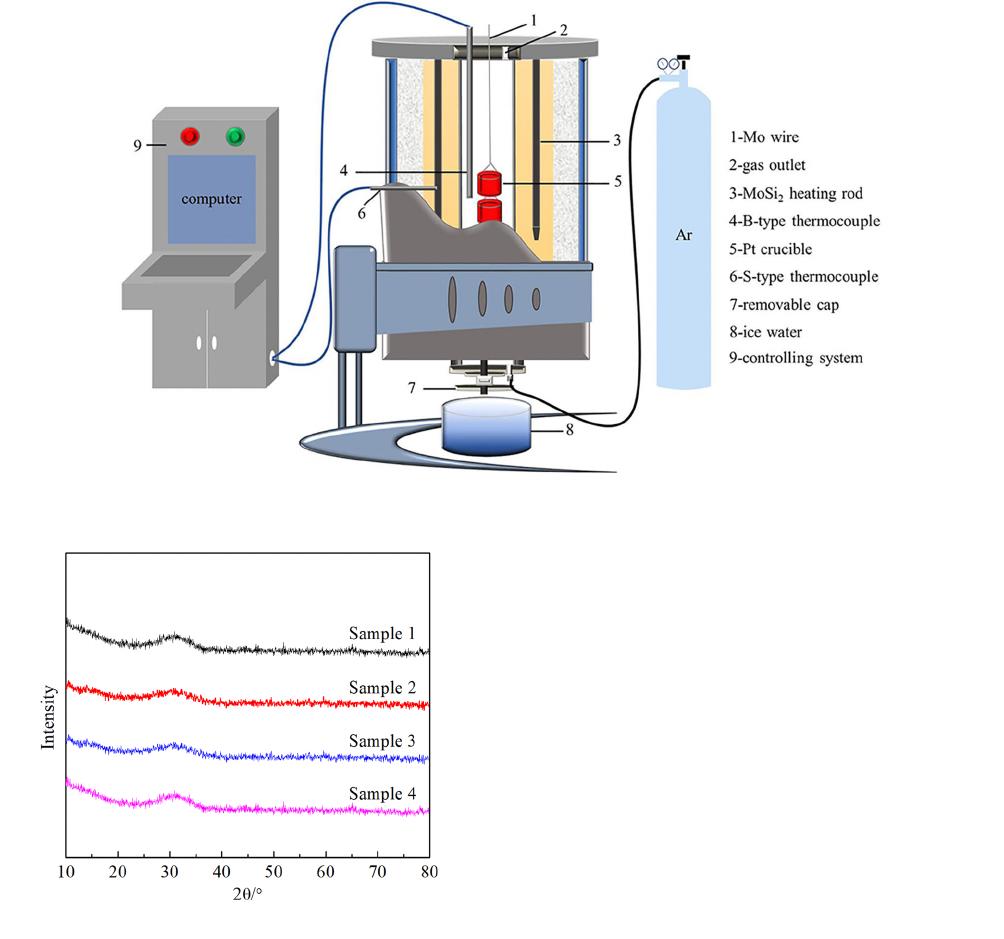

B. Pre-melted Slag Preparation

All the slag samples in the experiments were prepared

using analytical reagent grade CaO, SiO

2

and

Fe

2

C

2

O

4

Æ2H

2

O. When the temperature exceeds

1123 K, FeO can be obtained from the composi tion of

Fe

2

C

2

O

4

Æ2H

2

O.

[18]

CaO and SiO

2

were calcined at

1273 K for 4 h to remove moisture and volatile impu-

rities. The Fe

2

C

2

O

4

Æ2H

2

O powder was calcined at 873 K

for 4 h. Samples were loaded in a platinum crucible and

suspended with Mo wire in the constant temperature

zone of a high-temperature quenching furnace. The

schematic representation of a high-temperature quench-

ing furnace is shown in Figure 2. Thereafter, samples

were heated up to a temperature of 1873 K and held at

that temperature for 4 h to reach homogenization.

[19]

During the preparation of the sample, a constant flow

rate of argon (0.8 LÆmin

1

, purity > 99.9999 pct) was

maintained. The oxygen partial pressure of the system

was monitored by a ZrO

2

-CaO oxygen probe produced

by Australian Oxytrol Systems Pty. Ltd. The measured

oxygen partial pressure was controlled at about 10

10

atm, in which condition FeO was considered as the

coexistence of bivalent and trivalent irons in the molten

slags. A similar result was reported by Osugi et al.

[20]

Thereafter, the crucible fell rapidly into ice water by

opening the removable cap and loosening the Mo wire;

then, the quenched samples could be obtained.

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patte rns over the range

of 2h = 10 to 80 deg were performed using a X’pert

PRO diffractometer (PANalytiical, Holland), which

determined whether glassy samples were achieved. The

phase analyses of quenched samples are shown in

Figure 3. All the XRD profiles only showed a broad

peak around the diffraction angle 2h of 30. This

Fig. 1—Composition distribution of synthetic samples.

METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS B

so-called hola pattern confirmed that the samples were

amorphous.

[21]

Homogeneous glassy samples could be

considered to maintain the high-temperature state of the

melt structure and substituted the high-temperature

molten slag for analyzing the structures.

[22–24]

Additionally, compositions of glassy samples were

analyzed by an X-ray fluorescence spectrometer (S4

explorer, Germany). Yet, the iron ions in Fe

x

O could be

not specified as Fe

2+

or Fe

3+

by XRF, so the values of

Fe

2+

/

P

Fe and Fe

3+

/

P

Fe were ascertained by the

direct analysis of Fe

2+

using the K

2

Cr

2

O

7

titration

method (JIS M 8212:2005). The analyzed compositions

of glassy samples are listed in Table I and plotted in

Figure 1, which shows that the SiO

2

, CaO and total iron

contents are consistent with the designed compositions

of slag samples, and the values of Fe

3+

/Fe

2+

in glassy

samples are also close to redox ratio of iron in the

industrial slag.

[16]

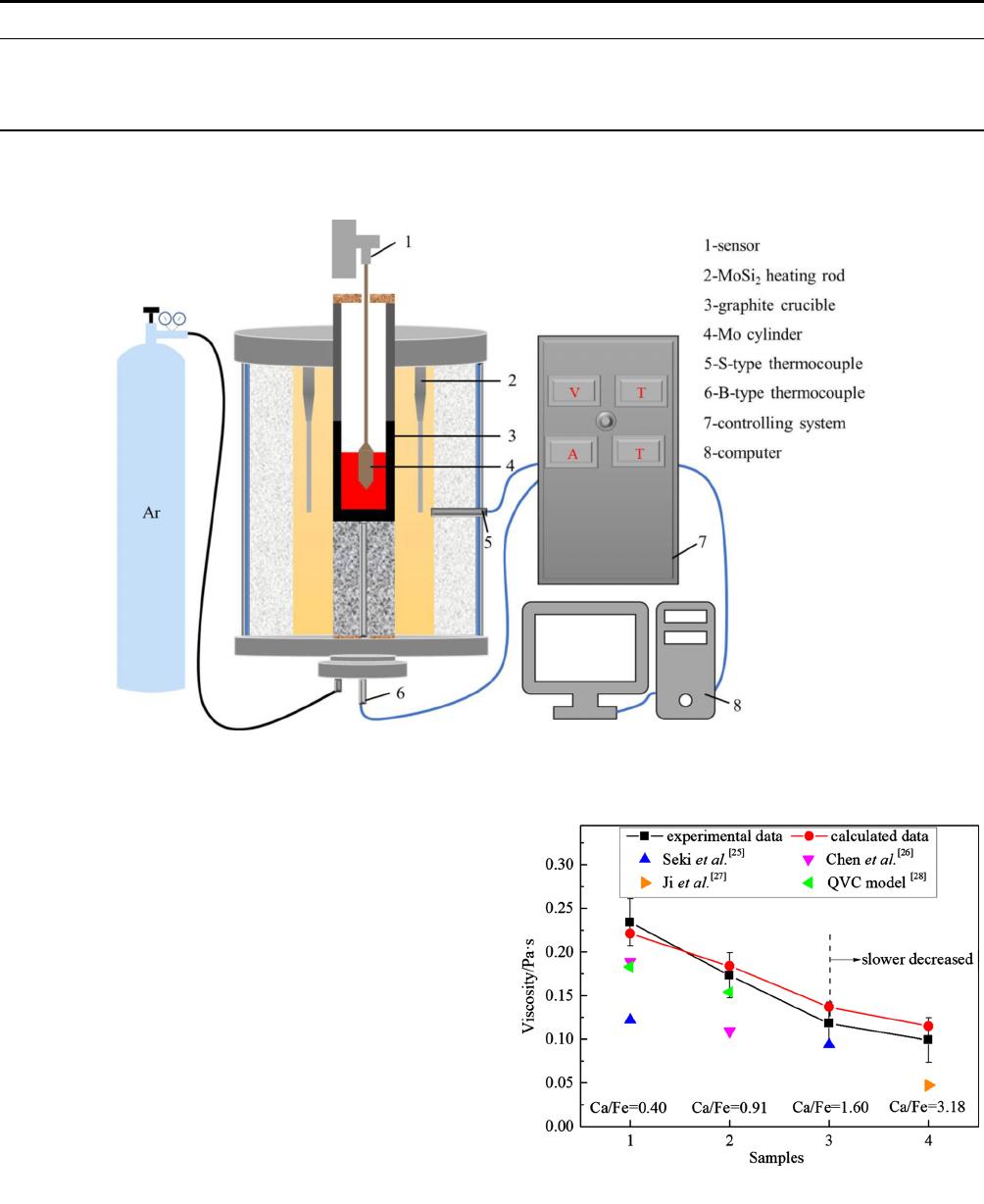

C. Experimental Method

The viscosity of experimental samples was measured

by the rotating cylinder method. The experimental

apparatus for high-temperature viscosity measurements

is shown in Figure 4. About 140 g of pre-melted slag

was put into the graphite crucible and heated to 1873 K

for 30 min. The viscosity of the measured sample

remained stable with altering rotation speed, indicating

that the molten slag had been completely melted and

was Newtonian fluid. Then, the viscosity of molten slag

was measured every other minute with a Mo spindle at a

constant temperature of 1873 K. The measurement of

each sample was carried out three times. Similar

experimental methods have been described in our

previous work elsewhere.

The measurements of melt structures were carried out

using a Raman spectrometer (JY-HR800, France).

About 1 mg of slag sample was flattened and placed

on the sample stage. The Raman spectra were recorded

by a multichannel modular triple Raman system with an

excitation wavelength of 488 nm and a 1-mW semi con-

ductor laser as a light source. The measured range of the

frequency band was from 100 to 4000 cm

1

, and the

resolution of the spectrum was 0.65 cm

1

.

Fig. 2—Schematic representation of high-temperature quenching furnace.

Fig. 3—X-ray diffraction pattern of quenched samples.

METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS B

III. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

A. Viscosity Analysis of Slag

The viscosity of CaO-SiO

2

-Fe

x

O slags with various

Ca/Fe ratios is shown in Figure 5. With the Ca/Fe ratio

increasing from 0.40 to 3.18, the average viscosity values

gradually decreased. A similar trend was reported by

Seki et al.

[25–28]

In addition, the viscosity of CaO-SiO

2

-

Fe

x

O slag shows a dramatic decrease at a lower Ca/Fe

ratio (0.40 to 1.60), while the viscosity decreases slowly

at a higher Ca/Fe ratio (1.60 to 3.18). Generally, the

viscous property of molten slag is affected by its

structure. For further clarification, the melt structures

of experi mental slags were also studied, and they will be

discussed in the following section.

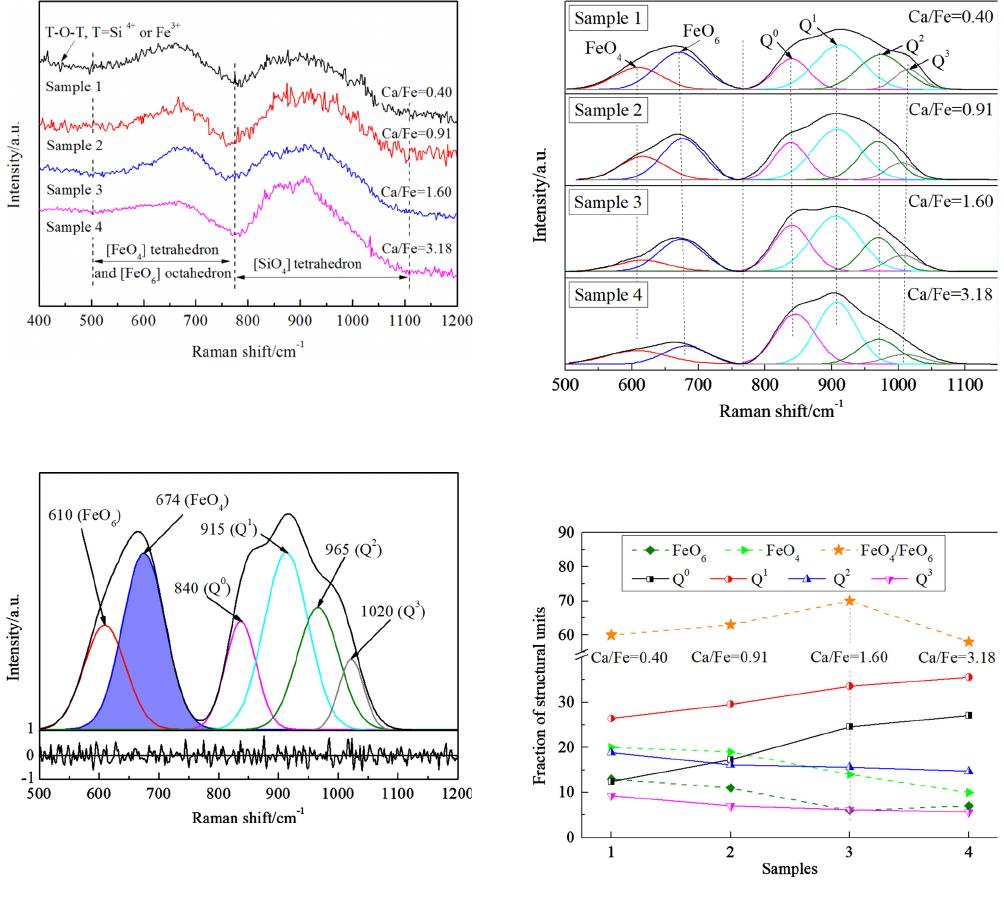

B. Microstructural Analysis of Viscosity

All the original Raman spectra of quenched slags are

presented in Figure 6. The spectra can be divided into

three regions: the low-fr equency region (LF: 400 to

500 cm

1

), intermediate-frequency region (MF: 500 to

780 cm

1

) and high-frequency region (HF: 780 to

1200 cm

1

). Accord ing to previous studies, different

regions correspond to the various structural vibrations.

The HF region has been traditionally interpreted as the

Table I. Analysis Result of Sample Compositions (Mass Percent)

Sample Basicity CaO SiO

2

FeO Fe

2

O

3

Fe

3+

/Fe

2+

Total Iron Ca/Fe

1 0.63 15.43 35.09 32.64 16.84 0.46 37.17 0.40

2 0.87 25.23 35.25 23.10 13.42 0.52 27.36 0.91

3 0.99 35.34 35.88 18.82 9.96 0.47 21.61 1.60

4 1.13 45.61 35.37 12.27 6.75 0.49 14.27 3.18

Fig. 4—Experimental apparatus for viscosity measurement.

Fig. 5—Viscosity of molten CaO-SiO

2

-Fe

x

O slags.

METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS B

convolution of bands related to symmetric Si-O stretch-

ing vibrations of units with variable numbers of bridging

oxygen (Q

n

: n being the number of BO).

[29–32]

Investi-

gations showed that the MF region was the overlapping

zone of the Fe-O and Si-O vibration. It was interpreted

as the convolution of bands related to symmetric Fe-O

stretching vibrations of FeO

4

and FeO

6

units

[33–36]

and

the convolution of bands related to Si-O stretching

vibrations and breathing modes of three- and four-mem-

bered ring structures of [SiO

4

] tetrahedrons.

[29–32]

Fig-

ure 6 shows that the peak intensity at 500 to 780 cm

1

steadily decreases with increasing Ca/Fe ratio, but it

does not show the obvious band related to the Si-O

vibration. Consequently, the MF region is deduced to be

mainly related to the Fe-O vibration. For the LF region,

it is usually attributed to the bending vibration involving

T-O-T bridging oxygen relative to almost stationary

four-fold coordinat ed cations in the TO

4

units, where T

refers to the fourfold cation (Si

4+

,Fe

3+

).

[37–39]

Based on the above results, Fe

3+

coordinated with four

oxygen atoms, as a network former, forms a [FeO

4

]

tetrahedron, and Fe

3+

coordinated with six oxygen

atoms, as a network modifier, form s a [FeO

6

] octahedr on.

However, the vibration related to Fe

2+

is not detected in

the Raman spectra, so Fe

2+

is considered a non-frame-

work cation, which acts as a charge compensation in the

molten slag. Similar results were obtained from Mysen’s

research.

[10]

In the present slags, the peak intensity of the

MF region decreases with varying Ca/Fe ratios, indicat-

ing that the structural beh avior of Fe

3+

has changed.

Meanwhile, the shifting shoulders of the envelope peak in

the HF region show that the different types of SiO

4

units

have also changed. These variations in Raman spectra can

affect the degree of polyme rization of the melt and thereby

alter the viscosity of molten slag. The structural evolu-

tions of Si

4+

and Fe

3+

will be further discussed by the

deconvolution method of Raman spectra.

Fig. 6—Raman spectra of quenched slags.

Fig. 7—Typical deconvolution of Raman spectra.

Fig. 8—Deconvolution result of Raman spectra.

Fig. 9—Fraction of structural units.

METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS B

In general, the measured curves of Raman spectra are

not on the same horizont al line because of the fluores-

cence effect. Consequently, baselines of curves over the

Raman shift of 500 to 1200 cm

1

were first subtracted.

Thereafter, the spectra were fitted using the Gauss ian

deconvolution function in the Origin 9.0 software. In

our fits, the band position, width and intensity were

treated as independent variables. The spectra were

statistically treated by minimization of residuals. What

is more, the characteristic peaks obtained from the

deconvolution results could be used to calculate the

corresponding areas by the integral method. The ratio of

the integral area to the sum of all the characteristic

peaks could give the fraction of a specific structural unit

in the molten slag. The typical dec onvolution of the

Raman spectra is shown in Figure 7. Currently, this

method has been widely used by scholars in the

deconvolution of Raman spectra.

[40–43]

In addition, some studies revealed that the Fe-O

vibration could probably exist in the HF region. For

example, Genova et al.

[44,45]

named the band at

~ 970 cm

1

of Raman spectra the ‘‘Fe

3+

band,’’ and

Muro et al.

[46]

reported that the band at ~ 980 cm

1

was

attributed to the anti-symmetric coupled mode of

FeO

4

-SiO

4

unit. In Figure 7, there is a weak shoulder

near 980 cm

1

in samples 1, 2 and 3. If an extra line

parameter denoting the Si-O-Fe bond is added at

980 cm

1

during the curve-fitting process, this peak

obtained from the deconvolution result will be covered

by the Q

2

band and its content is relatively less.

According to the result, the Si-O-Fe bond is considered

to be possibly derived from the Fe-containing Q

2

unit

because of the interconnecti on of FeO

4

and Q

2

units.

Consequently, the Raman spectra were deconvoluted

again without separately considering the assignment of

the Fe-O-Si bond.

The deconvolution results are shown in Figure 8. The

peaks near 610, 670, 840, 915, 965 and 1020 cm

1

were

confirmed as the structural units of FeO

6

, FeO

4

,Q

0

(SiO

4

), Q

1

(Si

2

O

7

), Q

2

(Si

2

O

6

) and Q

3

(Si

2

O

5

), respec-

tively.

[29–36]

The relative area fractions obtained from

the deconvolution results are shown in Figure 9.

The slag composition is a process of fixed SiO

2

content

and decreasing total iron content. Because the SiO

2

/

Fe

2

O

3

ratio increases, the relative fraction of the SiO

4

unit

obviously increases and the relative fractions of Fe-O

structural units ([FeO

4

] tetrahedron and [FeO

6

] octahe-

dron) steadily decrease. However, the relative fractions of

[SiO

4

] tetrahedrons with variable numbers of bridging

oxygen (Q

0

,Q

1

,Q

2

and Q

3

) and different types of Fe-O

structural units also have a significant change.

With the Ca/Fe ratio increasing from 0.40 to 1.60, the

most polymerized units of [SiO

4

] tetrahedrons (Q

3

and

Q

2

) de crease and the small polymerized units of [SiO

4

]

tetrahedrons (Q

1

and Q

0

) increase. Consequently, the

number of non-bridging oxygens increases and the

degree of depolymerization of molten slag decreases,

resulting in decreasing viscosity. Obviously, the reason

for depolymerization is that the O

2

ions dissociated

from CaO can cut off the Si-O-Si bonds of [SiO

4

]

tetrahedrons, causing SiO

4

units to depolymerize from

Q

3

to Q

0

. The depolymerization process is represented

by Eq. [1], which coincides with the depolymerization

mechanism proposed by Mysen et al.

[10]

Under the condition of increasing Ca/Fe ratio from 0.40

to 1.60, the sum of relative fractions of the [FeO

4

]

tetrahedron and [FeO

6

] octahedron gradually decreases,

but the FeO

4

/FeO

6

ratio increases markedly. In this stage,

most O

2

ions enter [SiO

4

] tetrahedrons, and only a small

part of O

2

ions surround Fe

3+

. With the increasing O

2

dissociated from CaO, Fe

3+

tends to combine with O

2

,

forming a [FeO

4

] tetrahedron, which promotes an increase

Fig. 10—Schematic diagram of the structural evolution of molten slag.

Si

2

O

5

(Q

3

, sheet)

Si

4

O

11

(Q

2

, double chain)

2Si

2

O

6

(Q

2

, single chain)

4SiO

4

(Q

0

, monomer)

2Si

2

O

6

(Q

2

, ring)

2Si

2

O

7

(Q

1

, dimer)

O

2-

2O

2-

O

2-

2O

2-

2O

2-

½1

METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS B

in the FeO

4

/FeO

6

ratio. Although the net-like structures

formed by Fe

3+

increase, depolymerization of the [SiO

4

]

tetrahedron is the main reason for decreasing viscosity.

Similar results were found in Ru

¨

ssel’s research.

[47]

With further increasing of the Ca/Fe ratio from 1.60 to

3.18, the [SiO

4

] tetrahedron shows the same depolymer-

ization behavior as the lower Ca/Fe ratio of molten slag.

However, the increasing fractions of Q

0

and Q

1

are less in

this stage, indicating that the effect of O

2

on the

depolymerization of the [SiO

4

] tetrahedron becomes

weaker when the Ca/Fe ratio is 3.18. This phenomenon

coincides with a slowly decreasing trend of viscosity of

molten slag over the range of Ca/Fe = 1.60 to 3.18.

Meanwhile, it is also observed that the relative fraction

of the [FeO

4

] tetrahedron decreases significantly and the

relative fraction of the [FeO

6

] octahedron stays constant.

The possible reason for the decreasing FeO

4

/FeO

6

ratio can

be explained as follows. When the Ca/Fe ratio of molten

slag is 1.60, much more non-bridging oxygen exists in the

melt structure, indicating that the degree of polymerization

of molten slag is in a lower state. With further increasing of

the Ca/Fe ratio, the O

2

in molten slag is relatively

excessive, which can depolymerize SiO

4

and FeO

4

groups

to simpler units such as SiO

4

and FeO

4

monomers. Because

the bond strength of Si-O (799.6 KJ/mol) is stronger than

that of Fe-O (390 KJ/mol), the SiO

4

monomer formed by

the Si-O bond is relatively compact while the FeO

4

monomer formed by the Fe-O bond is relatively loose.

Excessive O

2

can be more easily incorporated into the

FeO

4

monomer to form a FeO

6

octahedron, which leads to

better stabilization of the [FeO

6

] octahedron. Therefore,

increasing of the Ca/Fe ratio over the range of 1.60 to 3.18

favors the depolymerization of molten slag and further

decreases the viscosity of molten slag. A similar result has

been reported by Vada

´

sz et al.

[48]

who considered that the

coordination of central ferric atoms might be changed from

a tetrahedron to octahedron depending on the surplus of

free oxygen ions in the complex Fe

3+

anions. Bowker

et al.

[49]

found that Fe

3+

behaved primarily as a network

modifier in very low iron glasses, which also supports the

present experimental result.

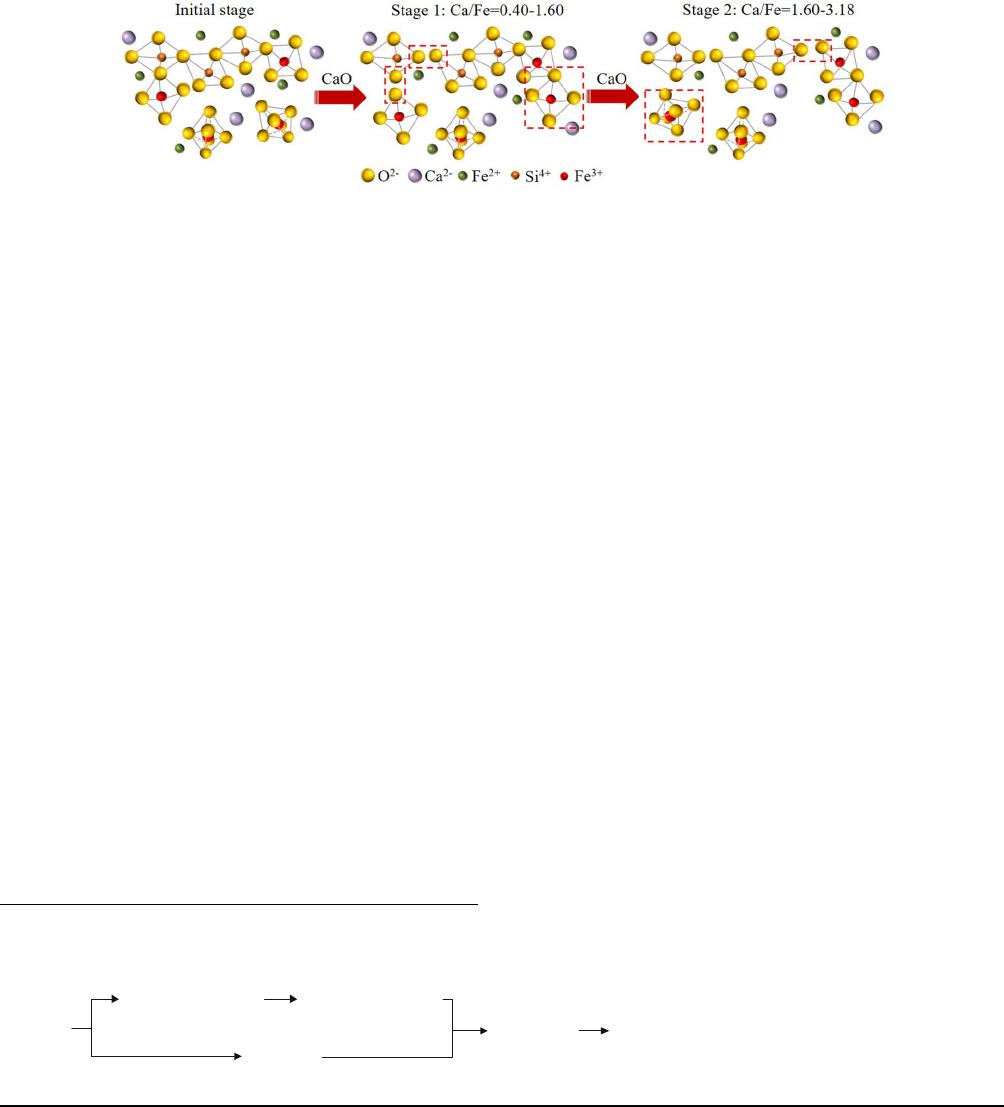

The schematic diagram of the structural behaviors of

Si

4+

and Fe

3+

in the melt are descri bed in Figure 10.

The structural evolution of molten slag is divided into

two stages in terms of different structural behaviors of

Fe

3+

. The Ca/Fe ratio increasing from 0.40 to 1.60 is

considered the first stage. In this stage, the [SiO

4

]

tetrahedron gradually depolymerizes from Q

3

to Q

0

and

the FeO

4

/FeO

6

ratio increases progressively. The Ca/Fe

ratio increasing from 1.60 to 3.18 is considered the

second stage. The [SiO

4

] tetrahedron further depoly-

merizes while the FeO

4

/FeO

6

ratio decreases. In these

two stages, the degree of polymerization of molten slag

gradually decreases, resulting in a continuous decrease

in the viscos ity of the molten slag.

C. Relationship Between Viscosity and Structure

The above results show a strong relationship between

the viscosity of molten slag and its structure. The higher

the degree of polymerization of the melt is, the larger the

viscosity of the molten slag is. Generally, three forms of

oxygen (brid ge oxygen O

0

, terminal oxygen O

and free

oxygen O

2

) are used to represent the degree of poly-

merization of molten slag. By adding some basic oxides

(such as CaO, Na

2

O) to silicate slag, O

and O

2

can be

generated by cutting off the bridging oxygen bonds of the

[SiO

4

] tetrahedron. O

and O

2

have greater fluidity than

O

0

because the oxygen is not connected to Si. Hence, the

numbers of O

and O

2

determine the viscosity of molten

slag. Nakamoto et al.

[50,51]

proposed a model for esti-

mating the viscosity of the silicate melt according to the

oxygen bonds. However, the viscosity model for the

Fe

2

O

3

-bearing silicate melt has not been studied so far. In

the present work, to establish a quantitative relationship

between the viscosity of molten slag and structure, the

viscosity estimation model for the CaO-SiO

2

-Fe

x

O slag

system is developed by applying the deconvolution results

of the Raman spectra.

For the silicate slag containing Fe

2

O

3

,Fe

3+

acts as

network former and can form Fe-O-Fe bonds (Fe-O

0

).

Therefore, when the chemical bonds of oxygen are

estimated, the Fe-O

0

bond should also be considered in

the viscosity equation proposed by Nakamoto et al.

except for three kinds of oxygen bonds related to Si. The

equation to calculate the viscosity of CaO-SiO

2

-Fe

x

O

slag is modified as follows:

g ¼ A expðE

v

=RTÞ½2

E

v

¼ E= 1 þ

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

X

i

a

i

NðO

þ O

2

Þ

i

þ

X

j

a

j

NðFe-O

0

Þ

j

q

½3

where E

v

is the activation energy; a

i

and a

j

are the

bond parameters of the slag component except SiO

2

and the non-frame cations, respectively; bond parame-

ters of CaO, FeO, Fe

2

O

3

,Ca

2+

and Fe

2+

are 4.00,

6.05, 1.00, 1.46 and 3.15,

[52]

respectively; N(O

+O

2

)

is the fraction of O

and O

2

, and N(Fe-O

0

) is the

fraction of O

0

in the [FeO

4

] tetrahedron; A is constant,

4.8 9 10

6

; E is the activation energy of pure SiO

2

,

5.21 9 10

5

J/mol.

The values of N(O

+O

2

) and N(Fe-O

0

) can be

calculated by relative fractions of structural units

obtained from Raman spectra instead of the evaluation

of the thermodynamic cell model proposed by Gaye

et al.

[53,54]

The calculated equations of N(O

+O

2

)

and N(Fe-O

0

) are shown in Eqs. [4] through [6] and the

calculated values are as shown in Table II.

NðO

þ O

2

Þ

i

¼ðN

O

NðSi - O

0

ÞNðFe - O

0

ÞÞ

n

i

=n

ðCaOþFeOþFe

2

O

3

Þ

½4

NðFe - O

0

Þ

j

¼ NðFeO

4

Þn

j

=n

ðCa

2þ

þFe

2þ

Þ

½5

NðSi-O

0

Þ¼3NðQ

3

Þþ2NðQ

2

ÞþNðQ

1

Þ; ½6

where i denotes CaO, FeO or Fe

2

O

3

; j denotes Ca

2+

and Fe

2+

; n

i

, n

j

denotes the fraction of i , j, respectively.

METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS B

The calculated viscosity obtained through Eqs. [2]and

[3] is shown in Figure 5. It is observed that the

calculated viscosity is in agreement with the measured

viscosity. The mean deviation (D) between the calculated

and experimental viscosities as defined in Eq. [7]is

shown in Table II.

D ¼ð1=NÞ

X

g

cal

g

exp

=g

exp

100 ð%Þ½7

where g

cal

and g

exp

are the calculated and measured

viscosities, respectively; N is the test number of

viscosity.

The mean deviations of all slags are almost within

20 pct, which is accep table for estimation of viscosity,

considering the reported experimental uncertainties of

25 pct. These results confirm that Eqs. [2] and [3]can

represent a reasonable estimation of viscosity in

CaO-SiO

2

-Fe

x

O slag systems during the early period

of basic oxygen steelmaking. The model is very useful

for estimating the viscosity of converter slag during the

early smelting period. The converter slag designer can

use this model to produce an appropriate slag that can

optimize the smelting performance to attain a satisfac-

tory metallurgical effect. Meanwhile, the estimation

model for viscosity can provide theoretical guidance

for designing the slagging route for basic oxygen

steelmaking.

IV. CONCLUSIONS

The viscosity of CaO-SiO

2

-Fe

x

O slags during the

initial period of basic oxygen steelmaking was analyzed

in terms of the structure of molten slags. The typical

conclusions are summarized as follows:

1. The viscosity of CaO-SiO

2

-Fe

x

O slags decreased

continuously with increasing Ca/Fe ratio, and the

Ca/Fe ratio showed an obvious influence on the vis-

cosity of molten slags. A more pronounced effect of

increasing Ca/Fe ratio on the decrease of viscosity

was revealed in the range of Ca/Fe = 0.40 to 1.61.

2. When the Ca/Fe ratio increased from 0.40 to 1.61,

increasing O

2

led to the depolymerization of [SiO

4

]

tetrahedrons from Q

3

to Q

0

units and an increasing

FeO

4

/FeO

6

ratio. Because depolymerization of [SiO

4

]

tetrahedrons was the main reaction, the degree of

polymerization of the molten slag gradually de-

creased and thereby decreased the viscosity of molten

slag in this stage.

3. With further increasing of the Ca/Fe ratio from 1.61

to 3.18, [SiO

4

] tetrahedrons were further depolymer-

ized, and more O

2

ions reacted with [FeO

4

] tetra-

hedrons to form [FeO

6

] octahedrons, resulting in a

decreasing FeO

4

/FeO

6

ratio. The variations of both

Si-O and Fe-O structural units caused a decrease in

the viscosity of molten slag.

4. The viscosity estimation model was established by

considering the Fe-O

0

in the melt structure and suc-

cessfully applied to the CaO-SiO

2

-Fe

x

O-based slag

system. In the model, the concentrations of bridging

oxygen, terminal oxygen and free oxygen were cal-

culated by decon volution results instead of estima-

tion derived from the thermodynamic cell model. The

model can estimate the viscosity of converter slag

during the early period of basic oxygen steelmaking

and design a reasonable converter slag to optimize

smelting perfor mance.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supp orted by the National Natural

Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 51674069,

51974075), the National Key R & D Program of Chi-

na (Grant No. 2017YFC0805100), the Open Funds of

State Key Laboratory of Metal Material for Marine

Equipment and Application (SKLMEA-K201911) and

the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central

Universities of China (Grant Nos. N182506001,

N180725008).

REFERENCES

1. J.J. Parka and R.J. Fruehan: Metall. Mater. Trans. B, 1991,

vol. 22B, pp. 39–46.

2. K. Gu, N. Dogan, and K.S. Coley: Metall. Mater. Trans. B, 2017,

vol. 48B, pp. 2595–2606.

3. J. Diao, P. Gu, D.M. Liu, L. Jiang, C. Wang, and B. Xie: JOM,

2017, vol. 69, pp. 1745–50.

4. G.H. Zhuang, K.C. Chou, Q.G. Xue, and K.C. Mills: Metall.

Mater. Trans. B, 2012, vol. 43B, pp. 64–72.

5. G.H. Kim and I. Sohn: J. Non-Cryst. Solids, 2012, vol. 358,

pp. 1530–37.

6. G.H. Kim, H. Matsuura, F. Tsukihashi, W.L. Wang, D.J. Min,

and I. Sohn: Metall. Mater. Trans. B, 2013, vol. 44B, pp. 5–12.

7. P.C. Li and X.J. Ning: Metall. Mater. Trans. B, 2016, vol. 47B,

pp. 446–57.

8. C. Feng, J. Tang, L.H. Gao, Z.G. Liu, and M.S. Chu: ISIJ Int.,

2019, vol. 59, pp. 31–38.

9. Y.M. Gao, S.B. Wang, C. Hong, X.J. Ma, and F. Yang: Int. J.

Miner. Metall. Mater., 2014, vol. 21, pp. 353–62.

10. B.O. Mysen, D. Virgo, and C.M. Scarfe: Am. Mineral., 1980,

vol. 65, pp. 690–710.

Table II. Fractions of Different Oxygen Atom Types and Mean Deviation of Viscosity

Sample NðO

+O

2

Þ

CaO

NðO

+O

2

Þ

FeO

NðO

+O

2

Þ

Fe

2

O

3

NðFe - O

0

Þ

Ca

2þ NðFe - O

0

Þ

Fe

2þ

D (Pct)

1 0.148 0.217 0.057 0.069 0.113 5.556

2 0.246 0.168 0.045 0.106 0.075 6.358

3 0.440 0.112 0.031 0.086 0.037 16.102

4 0.516 0.108 0.027 0.072 0.015 16.162

METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS B

11. D. Virgo and B.O. Mysen: Phys. Chem. Mineral., 1985, vol. 12,

pp. 65–76.

12. Z.J. Wang, Y.Q. Sun, S. Sridhar, M. Zhang, M. Guo, and Z.T.

Zhang: Metall. Mater. Trans. B, 2015, vol. 46B, pp. 2246–54.

13. T.F. Cooney and S.K. Sharma: J. Non-Cryst. Solids, 1990,

vol. 122, pp. 10–32.

14. G.A. Waychunas, G.E. Brown, C.W. Ponader, and W.E. Jacksom:

Nature, 1988, vol. 332, pp. 251–53.

15. W. Wu, Z.S. Zou, and Z.H. Guo: J. Iron Steel Res., 2004, vol. 16,

pp. 21–24.

16. M.Y. Zhu: Modern Metallurgical Technology, 1st ed., Beijing

Industrial Press, Beijing, 2011, pp. 207–309.

17. Y.Z. Wang, Y. Zhang, and W.H. Zhang: The Process and Equip-

ment of Oxygen Top Blown Converter Steelmaking, 2nd ed., Me-

tallurgical Industry Press, Beijing, 1983, pp. 33–40.

18. S. Caric

´

, L. Marinkov, and J. Slivka: Phys. Stat. Sol., 1975,

vol. 13, pp. 263–68.

19. J.A. Duff: J. Non-Cryst. Solids, 1996, vol. 196, pp. 45–50.

20. T. Osugi, S. Sukenaga, Y. Inatomi, Y. Gonda, N. Saito, and K.

Nakashima: ISIJ Int., 2013, vol. 53, pp. 185–90.

21. B.O. Mysen: Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta, 2006, vol. 70, pp. 2337–

53.

22. E.J. Jung and D.J. Min: Steel Res. Int., 2012, vol. 83, pp. 705–11.

23. M. Taylor, G.E.B. Jr and P.M. Fenn: Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta,

1980, vol. 44, pp. 109-17.

24. F.A. Seifert, B.O. Mysen, and D. Virgo: Geochim. Cosmochim.

Acta, 1981, vol. 45, pp. 1879–84.

25. K. Seki and F. Oeters: Trans. Iron Steel Inst. Jpn., 1984, vol. 24,

pp. 445–54.

26. M. Chen and B.J. Zhao: Metall. Mater. Trans. B, 2015, vol. 46B,

pp. 577–84.

27. F.Z. Ji, D. Sichen, and S. Seetharaman: Metall. Mater. Trans. B,

1997, vol. 28B, pp. 827–34.

28. M. Suzuki and E. Jak: Proc. VIIII Int. Conf. Molten Slags Fluxes

Salt, Beijing, 2012, pp. 68–83.

29. B.O. Mysen, D. Virgo, W.J. Harrison, and C.M. Scarfe: Am.

Mineral., 1980, vol. 65, pp. 900–14.

30. P.F. McMillan: Am. Mineral., 1984, vol. 69, pp. 622–44.

31. T. Furukawa, K.E. Fox, and W.B. White: J. Chem. Phys., 1981,

vol. 75, pp. 3226–37.

32. F.L. Galeene: Solid State Commun., 1982, vol. 44, pp. 1037–40.

33. B.O. Mysen, F.J. Ryerson, and D. Virgo: Am. Mineral., 1980,

vol. 65, pp. 1150–65.

34. G. Lucazeau, N. Sergent, T. Pagnier, A. Shaula, V. Kharton, and

F.M.B. Marques: J. Raman Spectrosc., 2007, vol. 38, pp. 21–33.

35. R. Iordanova, Y. Dimitriev, V. Dimitrov, and D. Klissurski: J.

Non-Cryst. Solids, 1994, vol. 167, pp. 74–80.

36. Z.J. Wang, Q.F. Shu, S. Sridhar, M. Zhang, M. Guo, and Z.T.

Zhang: Metall. Mater. Trans. B

, 2015, vol. 46B, pp. 758–65.

37. R.M. Santos, D. Ling, A. Sarvaramini, M. Guo, J. Elsen, F.

Larachi, G. Beaudoin, B. Blapain, and T.V. Gerven: Chem. Eng.

J., 2012, vol. 203, pp. 239–50.

38. A.A. Francis: J. Am. Ceram. Soc., 2005, vol. 88, pp. 1859–63.

39. A.A. Francis: Mater. Res. Bull., 2006, vol. 41, pp. 1146–54.

40. J.H. Park: J. Non-Cryst. Solids, 2012, vol. 358, pp. 3096–3102.

41. S. Sukenaga, N. Saito, K. Kawakami, and K. Nakashima: ISIJ

Int., 2006, vol. 46, pp. 352–58.

42. J. Yang, J.Q. Zhang, Y. Sasaki, O. Ostrovski, C. Zhang, D. Cai,

and Y. Kashiwaya: Metall. Mater. Trans. B, 2017, vol. 48B,

pp. 2077–91.

43. J. Qi, C.J. Liu, and M.F. Jiang: J. Non-Cryst. Solids, 2017,

vol. 475, pp. 101–07.

44. D.D. Genova, S. Sicola, C. Ramano, A. Vona, and S. Fanara:

Chem. Geol., 2017, vol. 457, pp. 76–86.

45. D.D. Genova, D. Morgavi, K. Hess, D.R. Neuville, N. Borovkov,

D. Perugini, and D.B. Digwell: J. Raman Spectrosc., 2015, vol. 46,

pp. 1235–1244.

46. A.D. Muro, N. Mtrich, M. Mercier, D. Giordano, D. Massare,

and G. Montagnac: Chem. Geol., 2009, vol. 259, pp. 78–88.

47. C. Ru

¨

ssel and A. Wiedenroth: Chem. Geol., 2004, vol. 213,

pp. 125–35.

48. P. Vada

´

sz, M. Havlı

´

k, and V. Daneˆ k: Can. Metall. Quart., 2000,

vol. 39, pp. 143–52.

49. J.C. Bowker, C.H. Lupis, and P.A. Flinn: Can. Metall. Quart.,

1981, vol. 20, pp. 69–78.

50. M. Nakamoto, J. Lee, and T. Tanaka: ISIJ Int., 2005, vol. 45,

pp. 651–56.

51. M. Nakamoto, T. Tanaka, J. Lee, and T. Usui: ISIJ Int., 2004,

vol. 44, pp. 2115–19.

52. M. Nakamoto, Y. Miyabayashi, L. Holappa, and T. Tanaka: ISIJ

Int., 2007, vol. 47, pp. 1409–15.

53. H. Gaye and J. Welfringer: Proc. 2nd Int. Symp. Metall. Slags and

Fluxes, TMA-AIME, Warrendale, PA, 1984, pp. 357–75.

54. H. Gaye, J. Lehmann, T. Matsumiya and W. Yamada: 4th Int.

Conf. on Molten Slags and Fluxes, ISIJ, Tokyo, 1992, pp. 103–08.

Publisher’s Note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to

jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS B