Vol.:(0123456789)

1 3

Japanese Journal of Radiology

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11604-020-00972-y

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Improved delineation ofCT virtual bronchoscopy

byultrahigh‑resolution CT: comparison amongdierent

reconstruction parameters

TakuyaAdachi

1

· HaruhikoMachida

2

· MakikoNishikawa

2

· TakahiroArai

1

· ToshiyaKariyasu

2

·

MasamichiKoyanagi

1

· KenichiYokoyama

2

Received: 27 December 2019 / Accepted: 3 April 2020

© The Author(s) 2020

Abstract

Purpose We compared the maximal recognizable bronchial bifurcation order (MRBBO) in CT virtual bronchoscopy (CTVB)

using ultrahigh-resolution CT (UHRCT) and different reconstruction parameters.

Materials and methods We enrolled 38 patients undergoing noncontrast chest CT by UHRCT and reconstructed CTVB

utilizing 3 different combinations of reconstruction parameters, as classified into Group A (matrix size, 512; slice thickness,

1.0mm), Group B (matrix size, 512; slice thickness, 0.5mm), and Group C (matrix size, 1024; slice thickness, 0.25mm). In

right S1, left S1 + 2, and both S3 and S10, two reviewers counted the number of consecutively identified bronchial bifurca-

tions to compare MRBBO among these groups using Kruskal–Wallis test.

Results In these segments, MRBBO increased from Group A to C. MRBBO was significantly higher in Group C than in

both Groups A and B in all the segments except left S10 (P < 0.05 for all). In left S10, it was significantly higher in Group

C than in Group A (P < 0.05) but comparable between Groups B and C (P = 0.122).

Conclusions MRBBO is higher in CTVB by UHRCT utilizing 1024-matrix size and 0.25-mm thickness than parameters

currently recommended for CTVB (matrix size, 512; slice thickness, 0.5–1.0mm).

Keywords CT virtual bronchoscopy· Maximal recognizable bronchial bifurcation order· Peripheral pulmonary lesions·

Ultrahigh-resolution CT

Introduction

Widespread use of multidetector computed tomography

(MDCT) scanners has increased the incidental detection

of peripheral pulmonary lesions (PPLs) subsequently diag-

nosed by surgical, percutaneous needle, or transbronchial

biopsy. The transbronchial method offers the lowest compli-

cation rate but can require tough insertion of a bronchoscope

and/or a biopsy instrument into the lesions [1].

In transbronchial biopsy, CT virtual bronchoscopy

(CTVB) is commonly used for navigation to assist scope

insertion and thus to improve diagnosis of PPLs because

of its 3-dimensional delineation of the tracheal and bron-

chial lumina as observed by actual bronchoscopy [2–4]. The

recent introduction of an ultrathin bronchoscope (external

diameter, ≤ 3mm) in CTVB navigation has required higher

spatial resolution to improve delineation of small peripheral

bronchi [5, 6]. To address this need and improve in- and

through-plane spatial resolution of CT images in clinical

settings, ultrahigh-resolution CT (UHRCT) scanners have

been introduced [7, 8]. However, we believe their utility for

CTVB has not been reported.

We therefore undertook this pilot study to compare the

maximal recognizable bronchial bifurcation order in CTVB

by UHRCT using different reconstruction parameters and

assessed whether use of UHRCT improved delineation of

CTVB compared to that obtained using standard MDCT.

* Haruhiko Machida

1

Department ofRadiology, Kyorin University Hospital,

6-20-2 Shinkawa, Mitaka, Tokyo181-8611, Japan

2

Department ofRadiology, Faculty ofMedicine, Kyorin

University, 6-20-2 Shinkawa, Mitaka, Tokyo181-8611, Japan

Japanese Journal of Radiology

1 3

Materials andmethods

Study population

We retrospectively identified 88 consecutive adult patients

who underwent noncontrast chest CT using a UHRCT

scanner (Aquilion Precision; Canon Medical Systems,

Tokyo, Japan) with superhigh-resolution (SHR) scan mode

(slice thickness, 0.25mm; number of detector channels,

1792) from April 1 through May 31, 2017 at our institu-

tion. We excluded 50 of the 88 whose image data were

deemed invalid for analysis because of significant CT

image artifacts due to poor breath-hold (n = one), inad-

equate positioning of the upper limb (one), and pulmonary

or bronchial structural distortions due to post-operative

(n = 13), interstitial pneumonia (13), pulmonary emphy-

sema (six), bronchiectasis (five), post-radiotherapy state

(four), non-tuberculous mycobacterial infection (two),

elevated diaphragm (two), pneumonia (one), bronchial

obstruction (one), and traumatic hemopneumothorax

(one). Thus, the final study population comprised 38

patients (17 men, 21 women; aged 24–89years, mean age

63 ± 15years) with mean body weight of 56.6 ± 9.9kg

(range 37.4–77.8kg) and body mass index (BMI) of

22.7 ± 3.4kg/m

2

(range 16.9–30.7kg/m

2

).

Our institutional review board approved this retrospec-

tive study, and we obtained written informed consent from

all patients.

CT scan technique

Patients underwent standard noncontrast routine helical

chest CT scanning covering the entire lungs in a cranio-

caudal direction during breath-hold using the UHRCT

scanner with the SHR scan mode (slice collimation,

0.25mm × 160 rows; number of channels, 1792). Scan

parameters were: tube voltage, 120kV; noise index, 12

Hounsfield units (HU) for the 5-mm reconstruction in fil-

tered back projection by automatic exposure control; heli-

cal pitch, 0.806; rotation time, 0.5s; and x-ray focus size,

0.4 × 0.5mm or 0.6 × 0.6mm. Just before each CT scan-

ning, we checked the maximal tube current displayed on

the CT console and selected the focus size of 0.4 × 0.5mm

unless the tube current exceeded 260mA because the max-

imal limitation of tube current is 260mA for the focus

size of 0.4 × 0.5mm and 310mA for that of 0.6 × 0.6mm.

We recorded the volume CT dose index (CTDI

vol

, meas-

ured in mGy) and dose length product (DLP, measured in

mGy・cm) displayed on the dose report on the CT scanner

for each patient and calculated the mean CTDI

vol

and DLP

for all patients.

CTVB image generation

For each patient, we used adaptive iterative dose reduction

(AIDR 3D Enhanced Strong; Canon Medical Systems) to

reconstruct the UHRCT image datasets with field of view

of 320–375mm and a kernel for mediastinal display (FC03)

utilizing 3 different combinations of reconstruction param-

eters including matrix size (512

2

and 1024

2

) and slice thick-

ness/interval (0.25/0.2, 0.5/0.4, and 1.0/0.8mm) (Table1).

All datasets were transferred to a dedicated worksta-

tion (SYNAPSE VINCENT version 4.6.0007; FUJIFILM

Medical, Tokyo, Japan), on which an experienced radiol-

ogy technologist reconstructed images by: applying an auto-

matic algorithm to extract the region of the bronchial wall

to generate 3-dimensional CTVB; simulating a pulmonary

nodule as a target lesion adjacent to the pleura of the most

apical part in Segment 1a of the right lung (right S1) and

Segment 1 + 2a of the left lung (left S1 + 2) and the most

anterior part of Segment 3b of the right lung (right S3) and

Segment 3b of the left lung (left S3) (both S3) and the most

basal part in Segment 10c of the right lung (right S10) and

Segment 10c of the left lung (left S10) (both S10) in each

patient; applying an automatic function to draw a tracking

line running through the center of the tracheal and bronchial

lumina to the nodule under each combination of reconstruc-

tion parameters; and adjusting the threshold to preserve con-

tinuity of the inner surface through the entire route under

each condition (Fig.1). We classified the CTVB image sets

with the 3 different combinations of reconstruction param-

eters into Groups A to C, with C having the smallest voxel

size (Table1).

CTVB assessment

Using a CTVB navigation mode, the experienced radiology

technologist and a board-certified radiologist observed the

CTVB images along the tracking line toward the simulated

nodules in the right S1, left S1 + 2, and both S3 and S10

using a paging method to confirm the absence of pathology

throughout the route for each patient. The 2 blinded review-

ers then assessed all the CTVB image sets of Groups A to C

in random order, and in consensus, they counted the number

Table 1 Three combinations of reconstruction parameters

Group Matrix size Slice thickness

(mm)

Slice

interval

(mm)

A 512 × 512 1.0 0.8

B 512 × 512 0.5 0.4

C 1024 × 1024 0.25 0.2

Japanese Journal of Radiology

1 3

of consecutively identified bronchial bifurcations (based on

the carina as the first bifurcation) to determine the maximal

recognizable bronchial bifurcation order in the right S1, left

S1 + 2, and both S3 and S10 for each group. The reviewers

confirmed identification of bronchial bifurcation when they

could clearly observe at least 2 bronchial orifices as they

moved back and forth at least 3 times.

Statistical analysis

All continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard

deviation (SD). We analyzed statistics using commercially

available software (IBM SPSS Statistics, version 23 IBM

SPSS, Armonk, NY, USA). We used Kruskal–Wallis test

to compare the maximal recognizable bronchial bifurcation

order in the right S1, left S1 + 2, and both S3 and S10 among

Groups A, B, and C. We selected Groups A and B as coun-

terparts to Group C because Group C had the smallest voxel

size, and the current recommendation for slice thickness for

CTVB using standard MDCT scanners with 512

2

matrix

size is 0.5–1.0mm [2]. In each segment and group, we used

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient to assess correla-

tion between the maximal recognizable bronchial bifurcation

order and BMI. A P value less than 0.05 was considered

statistically significant.

Results

We observed a mean CTDI

vol

of 12.8 ± 1.5mGy and mean

DLP of 581.6 ± 93.1mGycm.

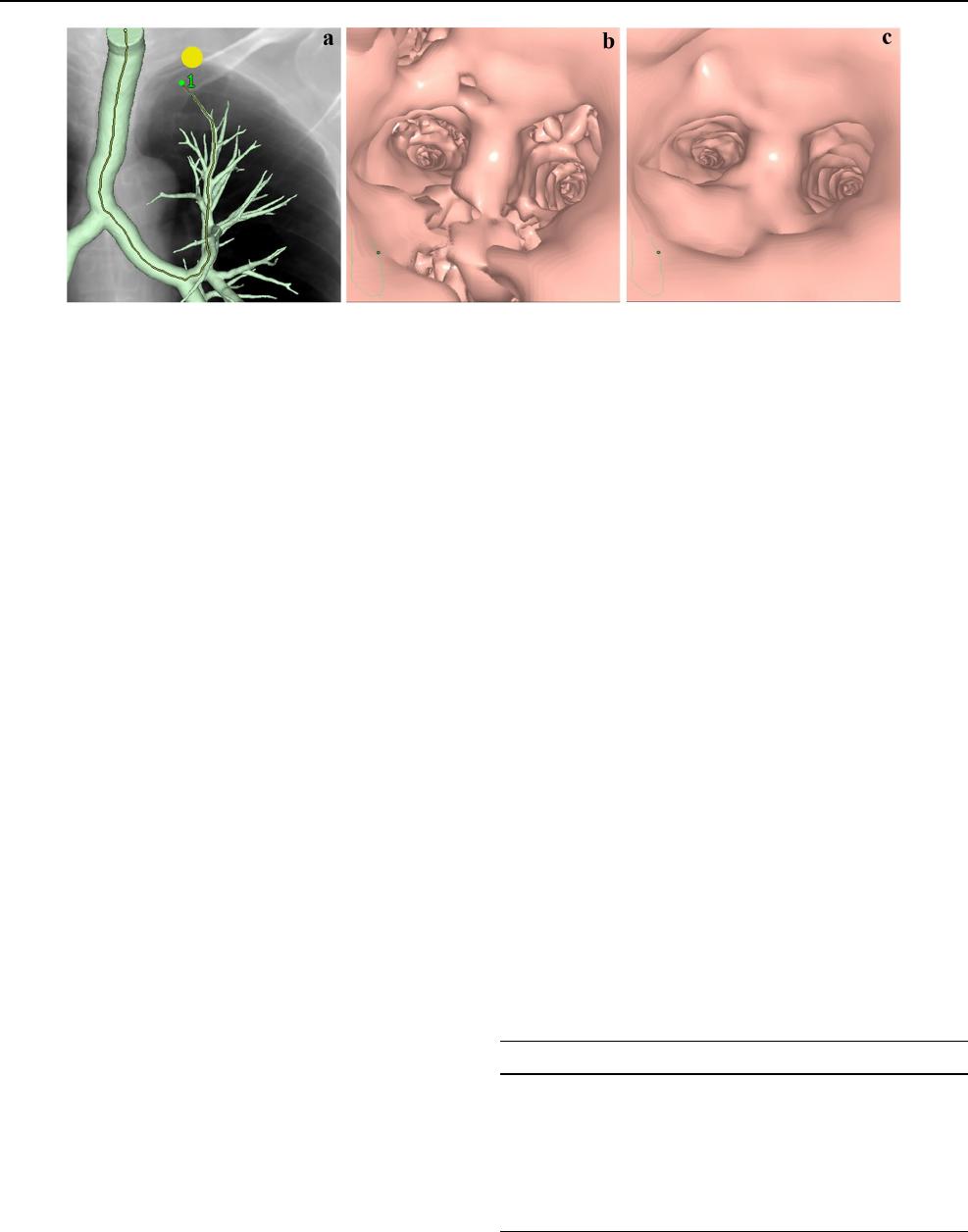

The maximal recognizable bronchial bifurcation order

tended to increase from Group A to Group C in the right

S1, left S1 + 2, and both S3 and S10 (Table2 and Fig.2).

The maximal recognizable bronchial bifurcation order was

significantly higher in Group C than in both Groups A

and B in all these segments except left S10 (P < 0.05 for

all); was significantly higher in Group C than in Group A

(P = 0.021) but comparable between Groups B and C in

left S10 (P = 0.122) (Fig.2). All of these values in Group

C were higher by one or more than in Groups A and B.

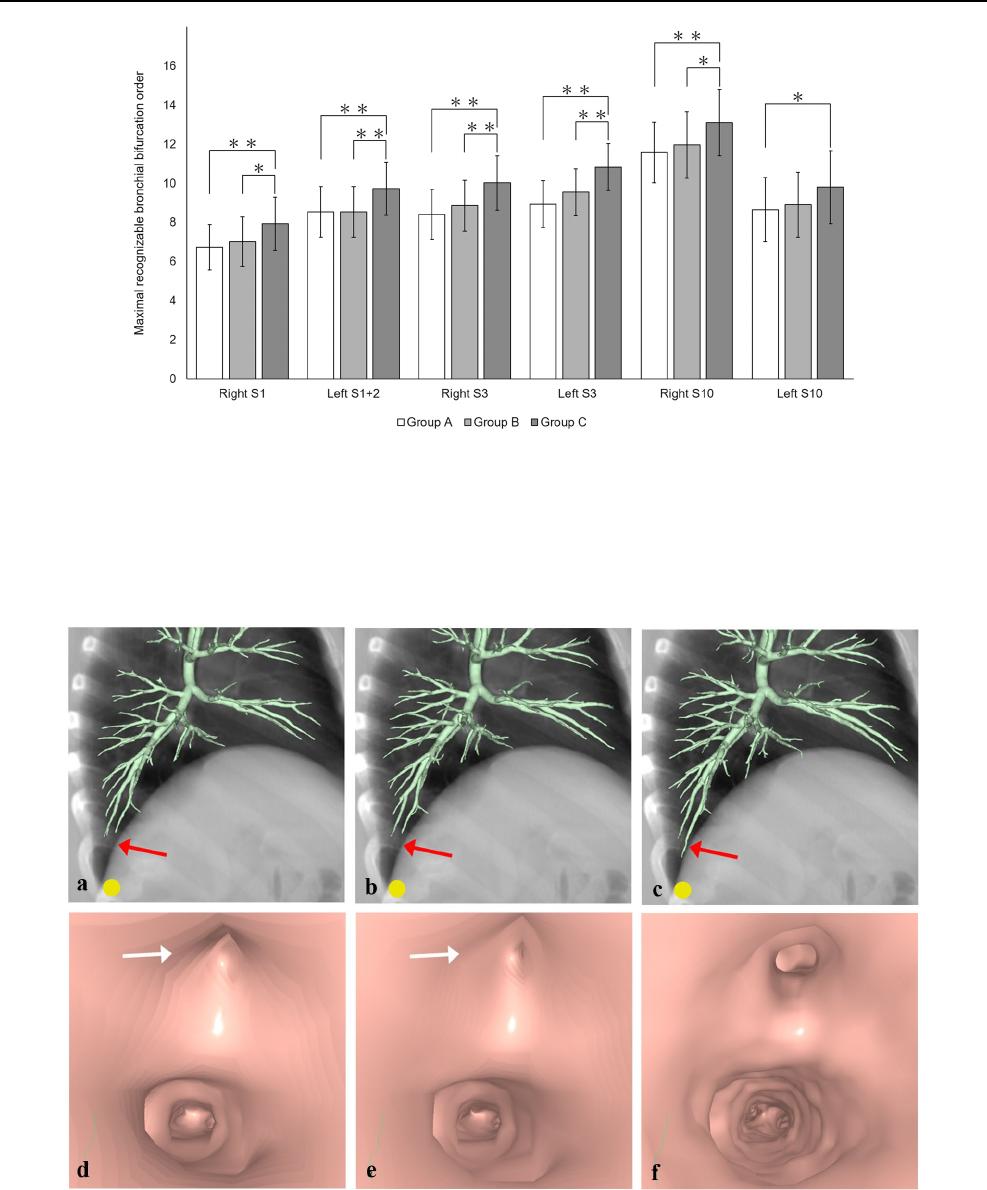

Figure3 shows the improved delineation of peripheral

bronchi and bronchial orifices at the maximal recogniz-

able bronchial bifurcation order in each patient in Group

C compared with delineation in Groups A and B in CTVB

images obtained using UHRCT. No significant correlation

was found between the maximal recognizable bronchial

bifurcation order and BMI in any segments and groups

(P = 0.320–0.989, ρ = − 0.191–0.188).

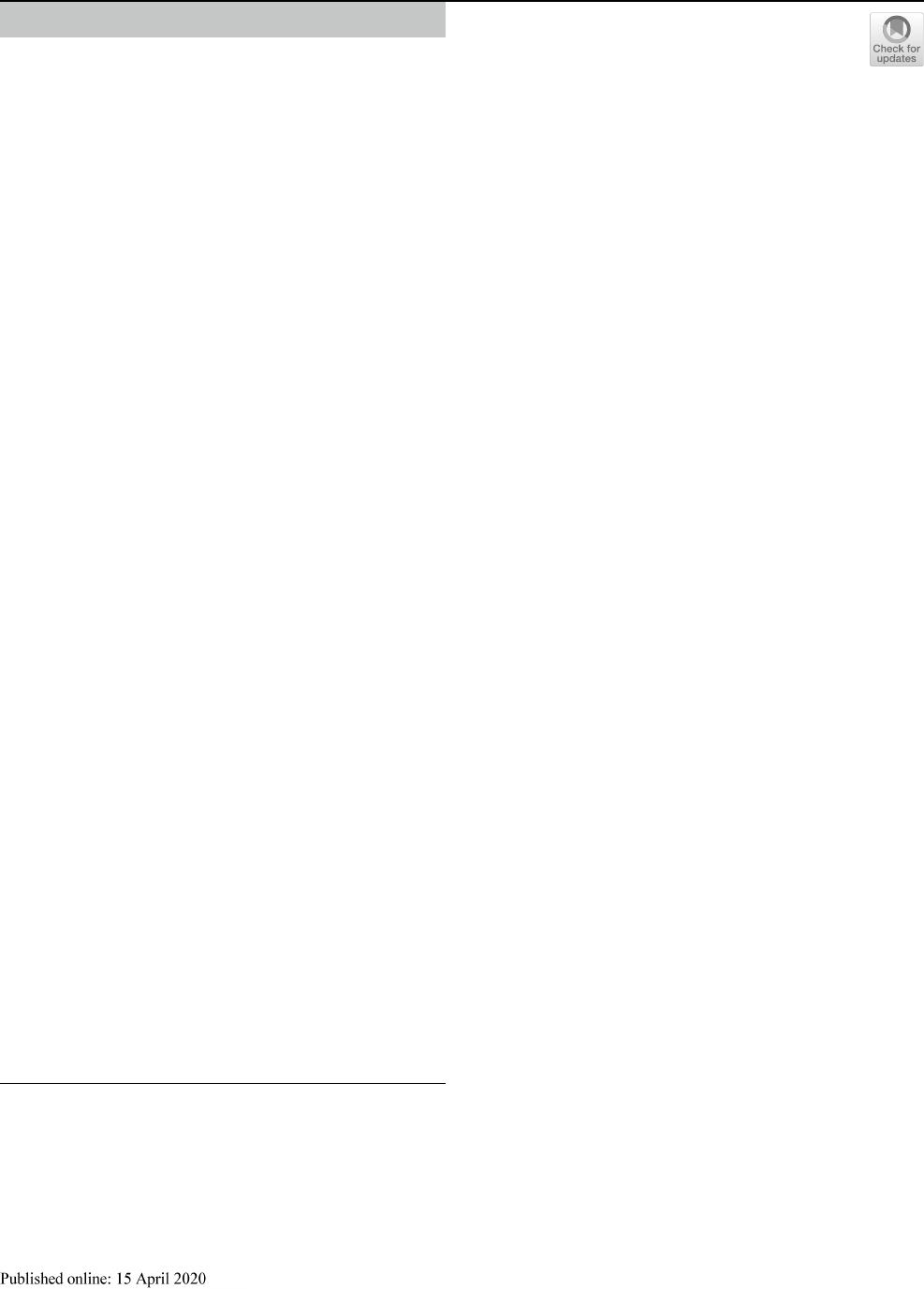

Fig. 1 Process of image generation for computed tomographic (CT)

virtual bronchoscopy (CTVB). A pulmonary nodule (yellow circle)

is simulated as a target lesion adjacent to the pleura of the most api-

cal part in Segment 1 + 2 of the left lung for CTVB on a simulated

chest radiograph, and a tracking line (yellow line) is then automati-

cally drawn running through the center of the tracheal and bronchial

lumina to the nodule on the frontal overlapped view of a volume-ren-

dered bronchial tree (a). The wall region of the tree has been auto-

matically extracted and the simulated chest radiograph reconstructed

from the same CT volume data. Endoscopic view of CTVB before

adjustment of the threshold to preserve continuity of the inner surface

of the bronchial tree through the entire route (b). Endoscopic view of

CTVB after threshold adjustment shows improved continuity (c)

Table 2 Comparison of maximal recognizable bronchial bifurcation

order among Groups A, B and C

Left S1 + 2 Segment 1 + 2a in the left lung, Left S3 Segment 3b in the

left lung, Left S10 Segment 10c in the left lung, Right S1 Segment 1a

in the right lung, Right S3 Segment 3b in the right lung, Right S10

Segment 10c in the right lung

Group A Group B Group C

Right S1 6.7 ± 1.2 7.0 ± 1.3 7.9 ± 1.4

Left S1 + 2 8.6 ± 1.3 8.6 ± 1.3 9.7 ± 1.4

Right S3 8.4 ± 1.3 8.9 ± 1.3 10.0 ± 1.4

Left S3 8.9 ± 1.2 9.6 ± 1.2 10.8 ± 1.2

Right S10 11.6 ± 1.5 12.0 ± 1.7 13.1 ± 1.7

Left S10 8.7 ± 1.6 8.9 ± 1.7 9.8 ± 1.9

Japanese Journal of Radiology

1 3

Fig. 2 Bar graphs show the maximal recognizable bronchial bifur-

cation order on computed tomographic (CT) virtual bronchoscopy

(CTVB) obtained using various reconstruction parameters in Seg-

ment 1a of the right lung (right S1), Segment 1 + 2a of the left lung

(left S1 + 2), Segment 3b of the right lung (right S3), Segment 3b

of the left lung (left S3), Segment 10c of the right lung (right S10),

and Segment 10c of the left lung (left S10). In all these segments,

the maximal recognizable bronchial bifurcation order increased from

Group A to Group C. Asterisk indicates statistically significant dif-

ferences by Kruskal–Wallis test between each combination (

*

P < 0.05

and

**

P < 0.01, respectively)

Fig. 3 Computed tomographic (CT) virtual bronchoscopy (CTVB)

for a simulated nodule (yellow circle) adjacent to the pleura of the

most basal part in Segment 10c of the right lung in a 73-year-old

man. On the lateral overlapped view of a volume-rendered bronchial

tree and a simulated chest radiograph reconstructed from the same

CT volume data (a–c), delineation of peripheral bronchi in this seg-

ment (red arrows) improved from Group A (a) to Group B (b) to

Group C (c). On the endoscopic view of CTVB at the 13th bifurca-

tion in the segment (d–f), 2 bronchial orifices are clearly identified in

Group C (f), but one of these orifices appears to be obstructed (white

arrows) in Groups A (d) and B (e). Detailed delineation of the bron-

chial inner surface is also better in Group C (f) than in Groups A (d)

and B (e)

Japanese Journal of Radiology

1 3

Discussion

As expected, we observed the highest maximal recogniz-

able bronchial bifurcation order in CTVB by UHRCT uti-

lizing matrix size of 1024

2

and slice thickness of 0.25mm,

and that order was significantly higher than that obtained

using the values currently recommended for CTVB using

standard MDCT scanners (matrix size, 512

2

; slice thick-

ness, 0.5 or 1.0mm) [2]. The UHRCT scanner used in

our study has been in clinical application since 2017 and

achieved higher spatial resolution (maximal spatial resolu-

tion, approximately 0.15mm or less) than that of standard

MDCT scanners, even with the same voxel size [7–10].

Physical specifications improved by UHRCT included

the SHR scan mode (slice thickness, 0.25mm; number

of channels, 1792) and smaller x-ray tube focus (small-

est, 0.4 × 0.5mm). In fact, delineation of the anatomy of

the temporal bone has been reported more conspicuous

utilizing the improved detector of UHRCT than depic-

tion achieved using standard MDCT, even with the same

voxel size [11]. In addition, UHRCT facilitates the use of

smaller voxel size to decrease partial volume averaging,

so the superiority of CTVB by UHRCT to that utilizing

standard MDCT has been shown in delineating more distal

bronchi while preserving the continuity of the bronchial

inner surface [4, 6].

The maximal recognizable bronchial bifurcation order

by UHRCT ranged from 7.9 ± 1.4 to 13.1 ± 1.7 (median,

10; mean, 10.2 ± 2.4) in Group C, higher than that reported

by standard MDCT [4, 6]. Specifically, in the study by

Asano and colleagues, the median order was 6 using 16-

or 64-detector-row CT with matrix size of 512

2

and slice

thickness of 0.5 to 1.0mm; in the study by Khan and col-

leagues, the mean order was 6.5 ± 0.3 using 16-detector-

row CT with matrix size of 512

2

and slice thickness of

0.75mm. An ultrathin bronchoscope allows more distal

insertion than a larger conventional bronchoscope with

external diameter of approximately 5 to 6mm, and maxi-

mal insertion of the thinner scope to the ninth order has

been reported (median, fifth order) [4]. Thus, use of

UHRCT can better assist this maximal insertion of the

ultrathin bronchoscope. For transbronchial biopsy, diag-

nostic yield can be improved and examination time and

risk of complication reduced by insertion of an ultrathin

bronchoscope to PPLs with the aid of CTVB navigation by

UHRCT employing matrix size of 1024

2

and slice thick-

ness of 0.25mm [1, 4].

The maximal recognizable bronchial bifurcation order

was higher in the left S1 + 2 than in the right S1, pre-

sumably because the bronchial anatomy tends to detour to

the apex more prominently in the left S1 + 2. Image noise

and beam-hardening artifact caused by surrounding bony

structures in this apical area might diminish bronchial

delineation compared with both S10. However, the use of

UHRCT in combination with model-based iterative recon-

struction can improve the maximal recognizable bronchial

bifurcation order in this apical region. We excluded from

analysis a patient with poor breath-hold but did not per-

form electrocardiographically gated chest CT scanning,

which offers higher radiation exposure to patients. Thus,

the maximal recognizable bronchial bifurcation order was

lower in the left S10 than the right S10 and comparable

between Groups B and C only in the left S10, presumably

because bronchial delineation might be more susceptible

to motion artifacts from cardiac pulsation in the left S10.

According to the vendor of our workstation, its automated

tracking function permits the automatic drawing of a track-

ing line into bronchi with inner diameter of at least one

mm. Thus, improvement of this function will even further

increase the maximal recognizable bronchial bifurcation

order in CTVB by UHRCT.

Study limitations

Our study was limited because it was retrospective and

included only a small study population at a single institution,

and we restricted our pilot assessment of maximal recogniz-

able bronchial bifurcation order to only the right S1, left

S1 + 2, and right and left S3 and S10, whereas we selected

the right S1 and left S1 + 2 as the most apical segments, both

S10 as the most basal segments, and both S3 where the bron-

chi run almost parallel to the axial CT plane. We did not use

actual bronchoscopy as a reference to confirm delineation of

bronchial orifices, and insertion of even an ultrathin bron-

choscope to the maximal recognizable bronchial bifurcation

order delineated using CTVB navigation by UHRCT may

not be possible [4]. Confirmation of the clinical utility of

CTVB navigation by UHRCT to assist actual bronchoscopy

and thus transbronchial biopsy may warrant a large-scale

multicenter prospective study. Further, we used the only

workstation at our institution that was capable of generating

CTVB by UHRCT with matrix size of 1024

2

or more, but its

limited capacity to process high-volume data did not permit

reconstruction of UHRCT images with maximal matrix size

of 2048

2

. Our findings may also have been influenced by

the smaller body weight and BMI of our Japanese patients

compared to that of average-sized patients in Western coun-

tries, and the noise index in our study was that commonly

used for routine chest CT at our institution and might be

relatively small. Nevertheless, both the CTDI

vol

and DLP

complied with the criteria for radiation dose to patients for

standard chest CT (CTDI

vol

, 30mGy; DLP, 650mGycm)

according to European guidelines on quality criteria for

CT [12]. The lower radiation dose may have affected our

results by increasing image noise, whereas more advanced

Japanese Journal of Radiology

1 3

reconstruction techniques for further reducing image noise,

such as model-based iterative reconstruction, are applicable.

The 2 blinded reviewers in consensus assessed the CTVB

image sets, which may result in a confirmation bias.

Conclusion

In conclusion, with preserving continuity of the bronchial

inner surface, CTVB by UHRCT using matrix size of 1024

2

and slice thickness of 0.25mm improves delineation of

bronchial bifurcation compared to that achieved using the

values currently recommended for CTVB (matrix size, 512

2

;

slice thickness, 0.5–1.0mm), and its clinical application for

navigation in transbronchial biopsy, particularly using an

ultrathin bronchoscope, may improve clinical management

for patients with PPLs.

Acknowledgements This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for

Scientific Research (C) 18K07643, the Japan Society for the Promotion

of Science, Japan.

Funding A Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) 18K07643, the

Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, Japan.

Compliance with ethical statement

This study was approved by our institutional review board.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attri-

bution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adapta-

tion, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long

as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source,

provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes

were made. The images or other third party material in this article are

included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated

otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in

the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not

permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will

need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a

copy of this licence, visit http://creat iveco mmons .org/licen ses/b y/4.0/.

References

1. Asano F, Aoe M, Ohsaki Y, Okada Y, Sasada S, Sato S, etal.

Deaths and complications associated with respiratory endoscopy:

a survey by the Japan Society for Respiratory Endoscopy in 2010.

Respirology. 2012;17:478–85.

2. Asano F, Eberhardt R, Herth FJ. Virtual bronchoscopic navigation

for peripheral pulmonary lesions. Respiration. 2014;88:430–40.

3. Ishida T, Asano F, Yamazaki K, Shinagawa N, Oizumi S, Moriya

H, etal. Virtual bronchoscopic navigation combined with endo-

bronchial ultrasound to diagnose small peripheral pulmonary

lesions: a randomised trial. Thorax. 2011;66:1072–7.

4. Asano F, Shinagawa N, Ishida T, Shindoh J, Anzai M, Tsuzuku A,

etal. Virtual bronchoscopic navigation combined with ultrathin

bronchoscopy. A randomized clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care

Med. 2013;188:327–33.

5. Summers RM, Shaw DJ, Shelhamer JH. CT virtual bronchoscopy

of simulated endobronchial lesions: effect of scanning, reconstruc-

tion, and display settings and potential pitfalls. AJR Am J Roent-

genol. 1998;170:947–50.

6. Khan MF, Herzog C, Ackermann H, Wagner TO, Maataoui A,

Harth M, etal. Virtual endoscopy of the tracheo-bronchial system:

sub-millimeter collimation with the 16-row multidetector scanner.

Eur Radiol. 2004;14:1400–5.

7. Kakinuma R, Moriyama N, Muramatsu Y, Gomi S, Suzuki M,

Nagasawa H, etal. Ultra-high-resolution computed tomography

of the lung: image quality of a prototype scanner. PLoS ONE.

2015;10:e0137165. https ://doi.or g/10.1371/journ al.pone.01371 65.

8. Hata A, Yanagawa M, Honda O, Kikuchi N, Miyata T, Tsukagoshi

S, etal. Effect of matrix size on the image quality of ultra-high-

resolution CT of the lung: comparison of 512 × 512, 1024 × 1024,

and 2048 × 2048. Academic Radiol. 2018;25:869–76.

9. Tanabe N, Oguma T, Sato S, Kubo T, Kozawa S, Shima H,

etal. Quantitative measurement of airway dimensions using

ultra-high resolution computed tomography. Respir Investig.

2018;56(6):489–96.

10. Yanagawa M, Hata A, Honda O, Kikuchi N, Miyata T, Uranishi

A, etal. Subjective and objective comparisons of image quality

between ultra-high-resolution CT and conventional area detec-

tor CT in phantoms and cadaveric human lungs. Eur Radiol.

2018;28(12):5060–8.

11. Yamashita K, Hiwatashi A, Togao O, Kikuchi K, Matsumoto N,

Momosaka D, etal. Ultrahigh-resolution CT scan of the temporal

bone. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;275:2797–803.

12. Menzel H, Schibilla H, Teunen D, eds. European guidelines on

quality criteria for computed tomography. Luxembourg: European

Commission, 2000. Publication No. EUR 16262 EN

Publisher’s Note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to

jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.