Risk of Pneumonia with Ticagrelor Versus Clopidogrel:

a Population-Based Cohort Study

J Gen Intern Med

DOI: 10.1007/s11606-020-06131-3

© Society of General Internal Medicine 2020

INTRODUCTION

Ticagrelor is a potent antiplatelet agent used in the manage-

ment of acute coronary syndromes (ACS) that exerts pleiotro-

pic effects, including anti-inflammatory

1

and anti-Gram-

positive antibacterial

2

activity, and may reduce pneumonia

complications.

3

The objective of this study was to compare the risk of

community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), predominantly

caused by the Gram-positive pathogen Streptococcus

pneumoniae, with ticagrelor versus clopidogrel among ACS

patients who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention

(PCI).

METHODS

We conducted a population-based cohort study by linking the

Alberta Provincial Project for Outcome Assessment in Coro-

nary Heart Disease (APPROACH) registry with administra-

tive data for hospitalizations, emergency department (ED)

visits, outpatient prescription fills, and laboratory data. We

previously compared major adverse coronary events with

ticagrelor versus clopidogrel.

4

We included patients ≥ 18 years old, discharged alive after

undergoing PCI for ACS from April 2012 to March 2016, who

filled a prescription for ticagrelor or clopidogrel ≤ 31 days

after PCI. We excluded individuals already prescribed these

medications prior to index admission. Medication exposure

and adherence (assuming an intended standard 1-year therapy

duration) were defined using outpatient prescription fills.

4

The primary outcome was hospitalization or ED visit for

non-viral CAP (discharge International Classification of

Diseases-10th Revision codes J13.x to J18.x

5

)within1year

after PCI. Secondary outcomes were individual components

of hospitalization for CAP and ED visit for CAP. Hazard

ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for ticagrelor

versus clopidogrel were obtained using Cox proportional-

hazard models, censored at time of P2Y

12

inhibitor switch,

prescription fill gaps (greater than days’ supply plus 15-day

grace period) or death, and adjusted for potential confounders

selected a priori: age, sex, Cardiac-Specific Comorbidity In-

dex,

6

smoking status, chronic pulmonary disease, p roton

pump inhibitor use, fiscal year, and adherence. Moreover,

we evaluated the primary outcome based on P2Y

12

inhibitor

adherence (≥ 80% versus < 80%). A sensitivity analysis using

propensity score matching was consistent with the primary

analysis (not shown; available upon request). The University

of Alberta Research Ethics Office approved this study with

consent waived because investigators were provided de-

identified data. Statistical significance was set at 2-sided p <

0.05. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute)

and R 3.4.3 (R Project for Statistical Computing).

RESULTS

Among 11,185 eligible patients, the median age was 61 years

(interquartile range 54 to 71) and 2760 (24.7%) were women

(Table 1). Ticagrelor users were younger, had fewer comor-

bidities, and were less likely to be women, current smokers, to

have chronic pulmonary disease, or use a proton pump inhib-

itor than clopidogrel users. Ticagrelor users were more adher-

ent, but more likely to switch to another P2Y

12

inhibitor.

Outpatient use of ticagrelor was associated with a lower risk

of hospitalization o r ED visit for CAP compared with

clopidogrel in the year following PCI for ACS, which

persisted in adjusted analysis (adjusted HR 0.64, 95% CI

0.47–0.88) (Table 2). These associations were consistent for

hospitalizations for CAP (HR 0.65, 95% CI 0.44–0.97) and

ED visits for CAP (HR 0.72, 95% CI 0.51–1.02), although the

latter was not statistically significant. Adherence ≥ 80% was

associated with fewer CAP hospitalizations or ED visits com-

pared with adherence < 80% in both clopidogrel users (2.7%

versus 4.2%; adjusted HR 0.69, 95% CI 0.52–0.91) and

ticagrelor users (1.4% versus 3.2%; adjusted HR 0.42, 0.25–

0.71); however, this was more pronounced with ticagrelor.

Received April 1, 2020

Accepted August 11, 2020

DISCUSSION

In this study, ticagrelor was associated with fewer hospitali-

zations or ED visits for CAP than clopidogrel. Moreover,

adherent ticagrelor users had a lower risk of the primary

outcome than non-adherent users. This study adds to recent

promising data suggesting that ticagrelor may have clinically

relevant antibacterial activity.

1–3

This study has limitations inherent to its observational

design. First, residual confounding may persist despite adjust-

ment for key confounders. Second, our definition for CAP

(restricted to events that resulted in hospitalization or ED visit)

may have excluded clinically relevant outcomes managed in

the ambulatory setting. However, this compromise was made

to maximize the likelihood that pneumonia diagnoses were

confirmed by imaging.

Among patients with ACS managed with PCI, ticagrelor

was associated with a reduced risk of hospitalization or ED

visit for community-acquired pneumonia comp ared with

clopidogrel. Future studies will need to determine the mecha-

nism so that targeted ticagrelor-derived agents without hem-

orrhagic risk can be developed for the management of

pneumonia.

Ricky D. Turgeon, BSc(Pharm), PharmD

1

Erik Youngson, MMath

2

Michelle M. Graham, MD

3

1

Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of

British Columbia,

Vancouver, BC, Canada

2

Alberta SPOR Support Unit, University of Alberta,

Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

3

Division of Cardiology, Faculty of Medicine and

Dentistry, University of Alberta,

Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

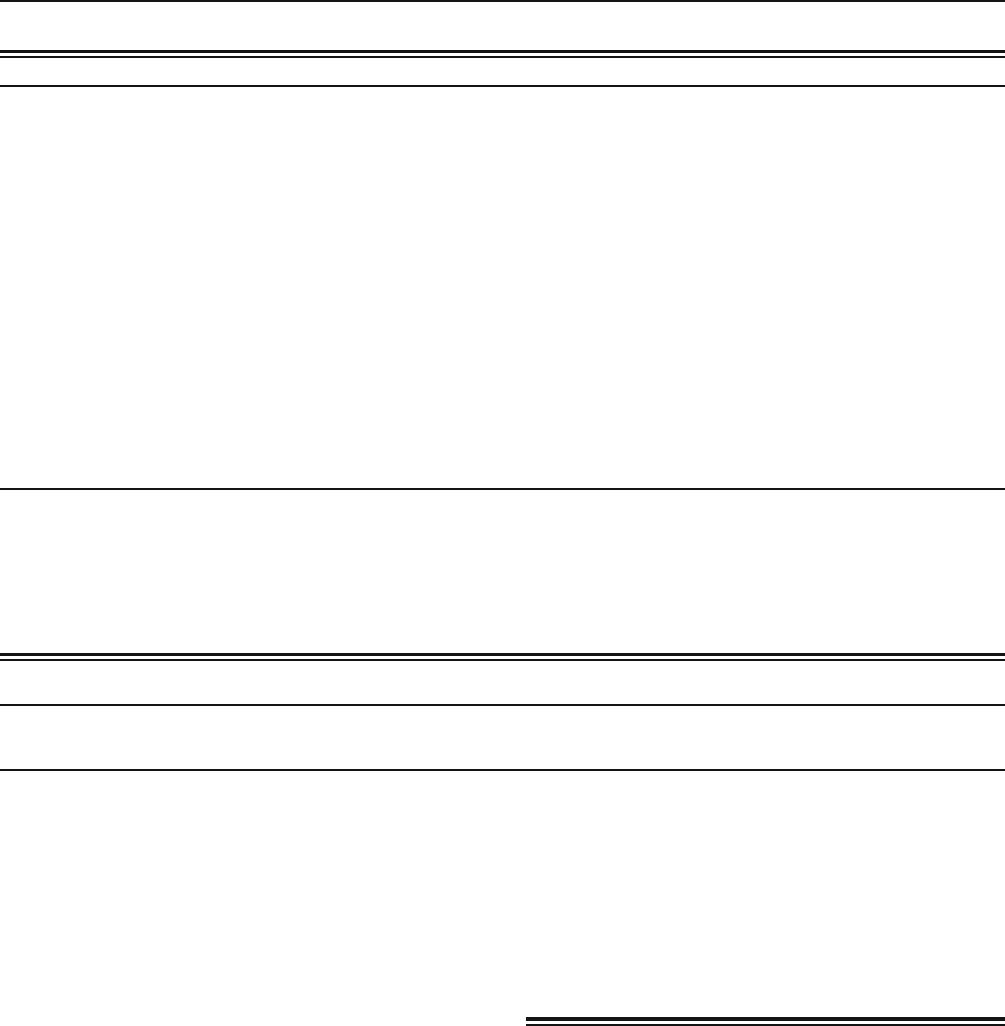

Table 1 Clinical Characteristics

Characteristic Clopidogrel (n = 7109) Ticagrelor (n = 4076) p value

Age, median (IQR), years 62 (54, 72) 60 (53, 69) < 0.0001

Women, No. (%) 1831 (25.8) 929 (22.8) 0.0005

ACS Type, No. (%) 0.0119

STEMI 3170 (44.6) 1783 (43.7)

NSTEMI/unstable angina 3910 (55.0) 2259 (55.4)

Unknown 29 (0.4) 34 (0.8)

Cardiac-Specific Comorbidity Index, median (IQR) − 5.4 (− 5.9, − 4.6) − 5.5 (− 6.0, − 4.9) < 0.0001

Medical history, No. (%)

Prior MI 858 (12.1) 287 (7.0) < 0.0001

Cerebrovascular disease 326 (4.6) 120 (2.9) < 0.0001

Heart failure 434 (6.1) 126 (3.1) < 0.0001

Diabetes mellitus 1807 (25.4) 968 (23.7) 0.0491

Smoking status < 0.0001

Current 2301 (32.4) 1060 (26.0)

Former 1580 (22.2) 715 (17.5)

Never/not recorded 3228 (45.4) 2301 (56.5)

Chronic pulmonary disease 714 (10.0) 147 (3.6) < 0.0001

eGFR, mL/min, median (IQR) 62 (61, 85) 81 (65, 93) < 0.0001

Proton pump inhibitor ≤ 31 days after PCI, No. (%) 2630 (37.0) 1270 (31.2) < 0.0001

Study P2Y

12

inhibitor utilization

MRA, median (IQR), % 98 (78, 101) 99 (88, 102) < 0.0001

MRA ≥ 80%, No. (%) 5256 (73.9) 3328 (81.6) < 0.0001

Switch, No. (%) 162 (2.3) 571 (14.0) < 0.0001

ACS, acute coronary syndrome; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; MI, myocardial infarction; MRA, medication refill adherence; NSTEMI,

non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; TIMI, thrombolysis in myocardial infarction

Table 2 Outcomes with Ticagrelor Compared with Clopidogrel

Outcome Clopidogrel

(n = 7109)

Ticagrelor

(n = 4076)

Unadjusted HR

(95% CI)

Fully adjusted HR*

(95% CI)

Primary outcome, n (%) 217 (3.1) 69 (1.7) 0.53 (0.40–0.71) 0.64 (0.47–0.88)

Hospitalization for CAP 140 (2.0) 41 (1.0) 0.48 (0.33–0.70) 0.65 (0.44–0.97)

ED visit for CAP 155 (2.2) 56 (1.4) 0.62 (0.45–0.85) 0.72 (0.51–1.02)

*Adjusted for baseline age, sex, current smoking, chronic pulmonary disease, Cardiac-Specific Comorbidity Index, proton pump use within 31 days

after PCI, fiscal year, and adherence using MRA as a continuous variable

CAP, community-acquired pneumonia; CI, confidence interval; ED, emergency department; HR, hazard ratio

Turgeon et al.: Ticagrelor and Risk of Pneumonia JGIM

Corresponding Author: Michelle M. Graham, MD; Division of

Cardiology, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Alberta,

Edmonton, Alberta, Canada (e-mail: mmg2@ualberta.ca).

Compliance with Ethical Standards:

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they do not have a

conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

1. Sexton TR, Zhang G, Macaulay TE, et al. Ticagrelor reduces

thromboinflammatory markers in patients with pneumonia. JACC Basic

Transl Sci 2018;3(4):435-449. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacbts.2018.

05.005

2. Lancellotti P, Musumeci L, Jacques N, et al. Antibacterial activity of

ticagrelor in conventional antiplatelet dosages against antibiotic-resistant

Gram-positive bacteria. JAMA Cardiol 2019;4(6):596-599. doi:https://doi.

org/10.1001/jamacardio.2019.1189

3. Storey RF, James SK, Siegbahn A, et al. Lower mortality following

pulmonary adverse events and sepsis with ticagrelor compared to

clopidogrel in the PLATO study. Platelets 2014;25(7):517-525.

doi:https://doi.org/10.3109/09537104.2013.842965

4. Turgeon RD, Koshman SL, Youngson E, et al. Association of ticagrelor vs

clopidogrel and major adverse coronary events in patients with acute

coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention.

JAMA Intern Med 2020;180(3):420-428. doi: https://doi.org/10.1001/

jamainternmed.2019.6447

5. Skull SA, Andrews RM, Byrnes GB, et al. ICD-10 codes are a valid tool for

identification of pneumonia in hospitalized patients aged > or = 65 years.

Epidemiol Infect 2008;136(2):232-240. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/

S0950268807008564

6. Azzalini L, Chabot-Blanchet M, Southern DA, et al. A disease-specific

comorbidity index for predicting mortality in patients admitted to hospital

with a cardiac condition. CMAJ 2019;191(11):E299-E307. doi:https://doi.

org/10.1503/cmaj.181 186

Publisher’sNoteSpringer Nature remains neutral with regard to

jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Turgeon et al.: Ticagrelor and Risk of PneumoniaJGIM