Eutectic Growth: Selection of Interlamellar Spacings

V. SEETHARAMAN and R. TRIVEDI

Critical experimental studies in a model transparent organic system have been carried out to estab-

lish the interlamellar spacing selection criterion for directionally solidified eutectic alloys. It is

shown that the spacing selection is not very sharp and a finite distribution of spacing is observed for

a given velocity. The width of the distribution is found to increase as the velocity is decreased. This

band of spacings is shown to lie within the stable zone predicted by the lamellar stability theory, and

the average spacing lies slightly above the value which corresponds to the minimum undercooling

condition. A number of velocity change experiments were also carded out in which the initial spac-

ing was either larger or smaller than the final spacing. For both these conditions, the average eutec-

tic spacing is found to drift toward the spacing value which is slightly larger than the smallest stable

spacing for the final velocity. All experimental results show that the stable range of eutectic spac-

ings is much smaller than that discussed by Jackson and Hunt.

I. INTRODUCTION

THE

growth of eutectic and eutectoid structures has

received considerable theoretical and experimental atten-

tion since these fine periodic microstructures give rise to

improved mechanical properties. [~-7] Furthermore, eutectic

or near-eutectic alloys can be directionally solidified to ob-

tain

in situ

composite structures. Two important parameters

of eutectic structures, which can be controlled experimen-

tally, are the relative volume fractions of the two phases

and the interlamellar spacing. The volume fractions are

controlled to some extent by the composition of the alloy, f8J

whereas the eutectic spacing is controlled by the imposed

growth rate.

Jackson and Hunt, in their already classic paper, tT] devel-

oped a detailed theoretical model to relate eutectic spacing

with the growth rate for directionally solidified alloys.

They solved the diffusion equation by assuming that the

lamellar fronts are locally flat and they considered the

average curvature of the lamellae only for determining

the average capillary undercooling at the solid-liquid inter-

face. Furthermore, they assumed that the diffusion distance

ahead of the interface is much larger than the interlamellar

spacing so that the periodic diffusion field can be character-

ized by the solution of the Laplace equation. Under these

assumptions, the relationship between the undercooling,

AT, at the solid-liquid interface and the eutectic spacing, h,

was obtained as

AT = Kl,kV + KJ,k,

[1]

where V is the growth rate. Kl and K2 are constant param-

eters for a given system and are defined in the Appendix.

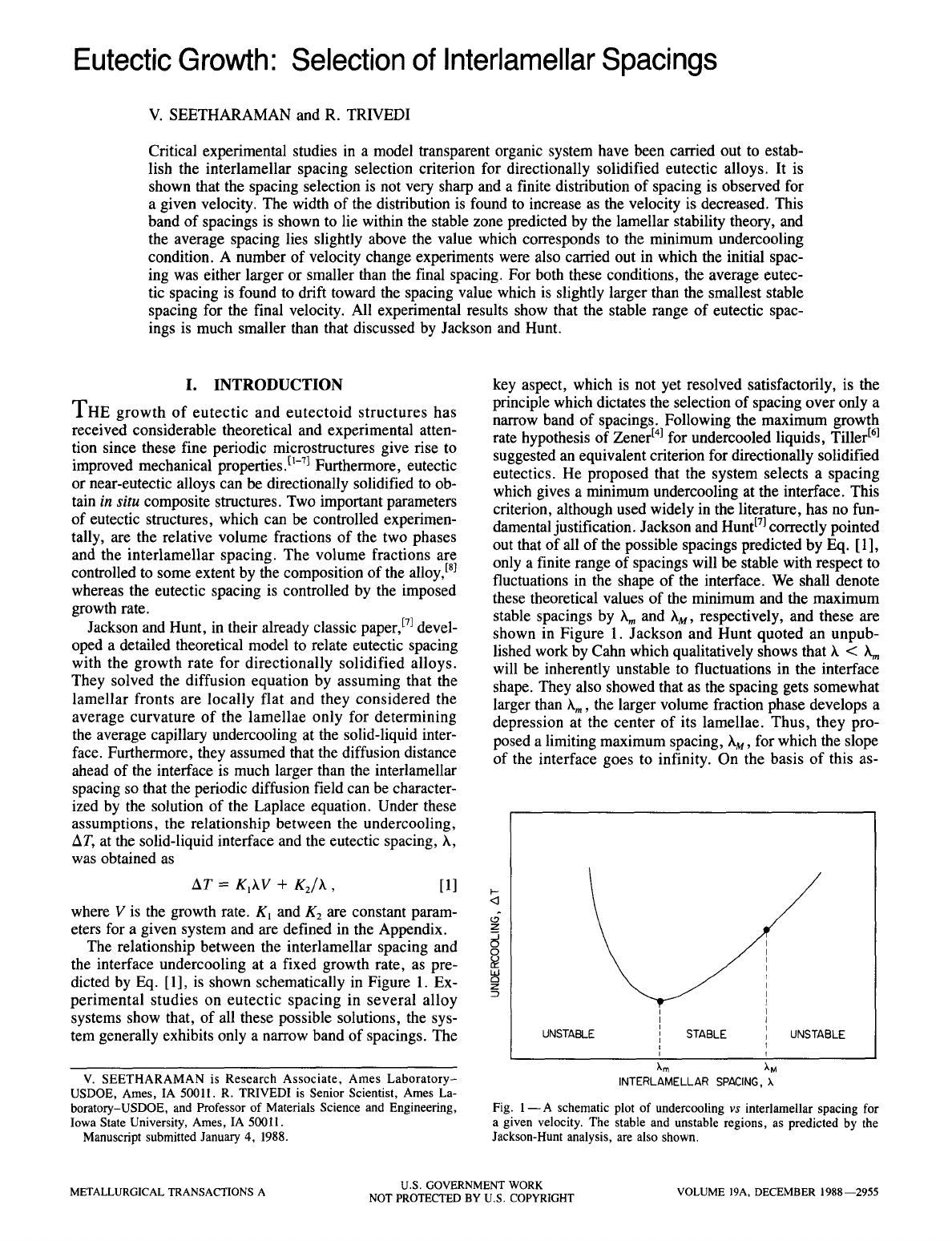

The relationship between the interlamellar spacing and

the interface undercooling at a fixed growth rate, as pre-

dicted by Eq. [1], is shown schematically in Figure 1. Ex-

perimental studies on eutectic spacing in several alloy

systems show that, of all these possible solutions, the sys-

tem generally exhibits only a narrow band of spacings. The

V. SEETHARAMAN is Research Associate, Ames Laboratory-

USDOE, Ames, IA 50011. R. TRIVEDI is Senior Scientist, Ames La-

boratory-USDOE, and Professor of Materials Science and Engineering,

Iowa State University, Ames, IA 50011.

Manuscript submitted January 4, 1988.

key aspect, which is not yet resolved satisfactorily, is the

principle which dictates the selection of spacing over only a

narrow band of spacings. Following the maximum growth

rate hypothesis of Zener t41 for undercooled liquids, Tiller trl

suggested an equivalent criterion for directionally solidified

eutectics. He proposed that the system selects a spacing

which gives a minimum undercooling at the interface. This

criterion, although used widely in the literature, has no fun-

damental justification. Jackson and Hunt E71 correctly pointed

out that of all of the possible spacings predicted by Eq. [1],

only a finite range of spacings will be stable with respect to

fluctuations in the shape of the interface. We shall denote

these theoretical values of the minimum and the maximum

stable spacings by hm and hM, respectively, and these are

shown in Figure 1. Jackson and Hunt quoted an unpub-

lished work by Cahn which qualitatively shows that h < h m

will be inherently unstable to fluctuations in the interface

shape. They also showed that as the spacing gets somewhat

larger than hm, the larger volume fraction phase develops a

depression at the center of its lamellae. Thus, they pro-

posed a limiting maximum spacing, hM, for which the slope

of the interface goes to infinity. On the basis of this as-

<3

~4

Z

s

I I

I I

I I

UNSTABLE I

STABLE Jl

UNSTABLE

I ,

Xm

~'M

INTERLAMELLAR SPACING, k

Fig. 1- A schematic plot of undercooling

vs

interlamellar spacing for

a given velocity. The stable and unstable regions, as predicted by the

Jackson-Hunt analysis, are also shown.

U.S. GOVERNMENT WORK

METALLURGICAL TRANSACTIONS A NOT PROTECTED BY U.S. COPYRIGHT VOLUME 19A, DECEMBER 1988--2955

sumption, they were able to derive simple analytical results

which related h,, and hM with the growth rate as follows:

Vh 2 = K2/K J,

and [2]

vx], = K3, [31

where

K 3

is a constant parameter which depends on the

properties of the system only. The expression for

K 3

is

given in the Appendix. The range of stable eutectic spac-

ings is shown schematically in Figure 1.

The basic ideas of eutectic stability, first proposed by

Jackson and Hunt, have subsequently been examined by a

number of detailed stability analyses of eutectic inter-

faces. 19-161 The most extensive theoretical studies by Langer

and coworkers I14A5'161 show that the smallest stable spacing

corresponds to the minimum undercooling value. These

theoretical models of eutectic stability do not predict a

unique spacing value for a given growth rate. Datye and

LangertlSJ pointed out that the system might drift toward the

lower marginal stability point, given by

hm.

This sugges-

tion is somewhat analogous to that for the dendrite tip

selection where the experimental studies show that the den-

drite tip radius assumes the marginally stable radius based

on the isothermal or the isoconcentrate interface model. It

should be pointed out that the dendrite tip selects the largest

stable radius value, whereas the minimum undercooling

criterion predicts that the eutectic system will select the

smallest stable spacing value. It is not very clear as to why

these two different systems will drift in different directions.

Also, there is no proper justification for the marginal sta-

bility criterion. One of the current thoughts t~7'~8'~91 on the

dendrite growth problem is that the anisotropy of the inter-

facial energy controls the stable dendrite tip radius. For

eutectic growth, anisotropy effects do not appear to be im-

portant, at least for the case of nonfaceted eutectic phases.

One would thus expect that a range of eutectic spacings,

h,, < h < kin,

is possible. We shall now examine some of

the experimental studies which give some insight into the

actual observed spacings.

The variations in average eutectic spacing with growth

rate have been measured in many eutectic systems, and all

the results show that

Vh 2

= constant for low growth rates.

The values of the constants for different systems have been

summarized by Kurz and Sahm. t2~ These experimental re-

suits have often been interpreted as the justification for the

minimum undercooling principle. It is not well appreciated

in the literature that the largest stable spacing also gives a

similar result; see Eqs. [2] and [3]. The specific value of

the theoretical constants will, however, depend on whether

the spacing is established close to Am or h M. Often, the

system parameters are not known precisely and this makes

it difficult to interpret unambiguously where the operating

point of the eutectic spacing lies. For lead-tin and alu-

minum-copper systems, the system parameters have been

measured independently and accurately. In these systems

the average spacing is found to be close to but slightly

larger than

hm.t2~-241

A more detailed study on eutectic spac-

ings in the Pb-Sn system has been carded out by Jordan and

Hunt, t241 who observed a range of eutectic spacings for a

given velocity. This range is quite narrow at high veloci-

ties, although it is significantly larger at low velocities. In

this regard it is worthwhile to note the experimental studies

by Kurz and coworkers 12s-28~ on faceted-nonfaceted eutec-

tics in which the eutectic spacing oscillates between

hm

and hM.

The above experimental studies clearly indicate that

there is no sharp selection criterion for eutectic spacing.

It is then puzzling as to why the average eutectic spac-

ings tend to be closer to

hm

rather than midway between hm

and hM. In order to examine the eutectic spacing selection

problem in more detail, we have carried out critical experi-

mental studies in a transparent eutectic system. Initially,

steady-state eutectic lamellar structures were examined to

characterize precisely the distributions of spacings at differ-

ent velocities. These studies allowed us to characterize the

variations in the average, the smallest, and the largest spac-

ing with the growth rate. Subsequently, dynamical studies

were carried out to see how these observed distributions

evolve with time. Specifically, we have approached a given

velocity by initially stabilizing the eutectic spacings at a

smaller spacing

(i.e.,

higher velocity) or at a larger spacing

(i.e.,

lower velocity). In both cases, the spacing is found

to drift toward

hm

and stabilize at values slightly larger

than

h m .

A small hysteresis effect is found for the average

spacing value. In all cases spacings close to hM have been

found to drift toward the

h m

value, indicating that the range

of stable eutectic spacing is significantly smaller than that

proposed by Jackson and Hunt. [71

II. EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

A. Materials and Cell Preparation

Experimental studies were carried out in carbon tetra-

bromide (CBr4)-hexachloroethane

(C2C16)

system which is

a transparent organic analog for nonfaceted, lameUar eutec-

tic structures. The equilibrium phase diagram for this sys-

tem has been determined by several authors.I29-321 Although

there are some discrepancies among these diagrams, par-

ticularly with respect to the maximum solid solubility of

C2C16 in CBr4 (c~ phase), there is a reasonably good agree-

ment on the following features: eutectic temperature =

356 K; eutectic composition = 8.4 wt pct

C2C16;

melting

point of CBr4 = 364.8 K, and melting point of

C2C16 :

459.6 K. Pure carbon tetrabromide solidifies with a face-

centered cubic structure with a lattice constant of 8.82/k.

It undergoes a transition to a monoclinic phase at 321.4 K.

Pure hexachloroethane also solidifies into a cubic form with a

lattice constant of 7.51/~ and undergoes a solid state transi-

tion to a triclinic phase at 344.3 K. Additional values of the

thermal and physical properties of the a and fl phases have

been measured by Kaukler. f321 Only the value of the inter-

diffusion coefficient has not been measured independently.

The commercial grade carbon tetrabromide was purified

by the vacuum sublimation process. This consisted of heat-

ing carbon tetrabromide at approximately 330 K under a

pressure of 100 mm Hg and allowing its vapors to condense

at -230 K. In contrast, the hexachloroethane could be sub-

limed at atmospheric pressure and at 320 K and then con-

densed at 290 K. These purified materials were mixed,

melted, and filled in specially fused glass cells which had

two narrow openings for filling the cell with the alloy.

Since the vapor pressures of both CBr4 and C2C16 are quite

appreciable at the eutectic temperature, it was necessary to

2956--VOLUME 19A, DECEMBER 1988 METALLURGICAL TRANSACTIONS A

carry out the melting and filling operations in a specially

constructed glass apparatus. In this apparatus a net positive

pressure of argon was applied to force the liquid alloy into

the glass cell and fill it completely. Soon after the filling,

the cells were removed and cooled quickly to ambient tem-

perature in order to prevent macrosegregation of the com-

ponents during the solidification of the alloy. The two small

openings in the cell were then sealed with an epoxy.

B. Directional Solidification Experiments

Directional solidification experiments were carried out

by using an apparatus which is described in detail by Mason

and Eshelman.I33J It consisted of a temperature gradient

stage, drive mechanism, and the measuring and recording

systems. The glass cell was held between the hot and cold

chambers of the temperature gradient stage. The tempera-

tures of these chambers were adjusted such that the portion

of the sample in the hot chamber was molten and that in the

cold chamber was frozen. Directional solidification of the

sample was induced by moving the cell from the hot cham-

ber to the cold chamber by means of a computer controlled

high precision ground lead screw mechanism. An optical

microscope and camera system were mounted such that the

solid/liquid interface present in the gap between the hot and

cold chambers could be viewed and recorded continuously.

The temperature gradient at the interface was measured

from the temperature profile obtained from a calibrated,

low inertia thermocouple which was placed inside the cell.

The solidification velocity was monitored with the help of a

linear variable differential transformer coupled with an elec-

tronic differentiator. 134]

The directional solidification experiments on CBr 4-

8.4 wt pet

C2CI 6 were

conducted using a temperature gra-

dient, G = 3.6 K/mm, and at velocities ranging from 0.1

to 20/zm/s. Since CBr4 tends to break down (particularly

in the presence of

C2C16) at

high temperatures to yield

bromine, it was necessary to keep the hot chamber tempera-

tures quite low (388 K), and this placed an upper limit on

the temperature gradient. At G = 3.6 K/ram, the eutectic

interface remained flat at a macroscopic level only at ve-

locities below 2.0/~m/s. At velocities above this value the

eutectic interface exhibited a tendency to assume a cellular

morphology. In view of this transition from planar to cellu-

lar morphology of the eutectic interface all the lamellar

spacing data presented in this paper were restricted to the

velocity range of 0.1 ~< v ~ 2.0/xm/s.

All the experiments were conducted with a constant cell

thickness of 150/xm. At this thickness level, the convection

effects in the liquid have been found to be negligible.t351 At

the same time, this thickness would minimize the curva-

ture of the solid/liquid interface in the vertical plane. This

thickness, however, would influence the kinetics of spacing

adjustment and this will be discussed by examining sev-

eral cases with different sample thickness to lamellar spac-

ing ratios.

Two sets of solidification studies were carried out in

these experiments. In the first set, the sample was initially

held at Vo = 0 for at least one hour and then the velocity

was quickly changed to the desired value, V, and held at

this velocity until the steady state growth conditions were

obtained. A steady state condition was considered to be

present when the interface position, as observed under the

microscope, did not change with time over a sufficiently

large period of time, so that the interface velocity was equal

to the externally imposed velocity.

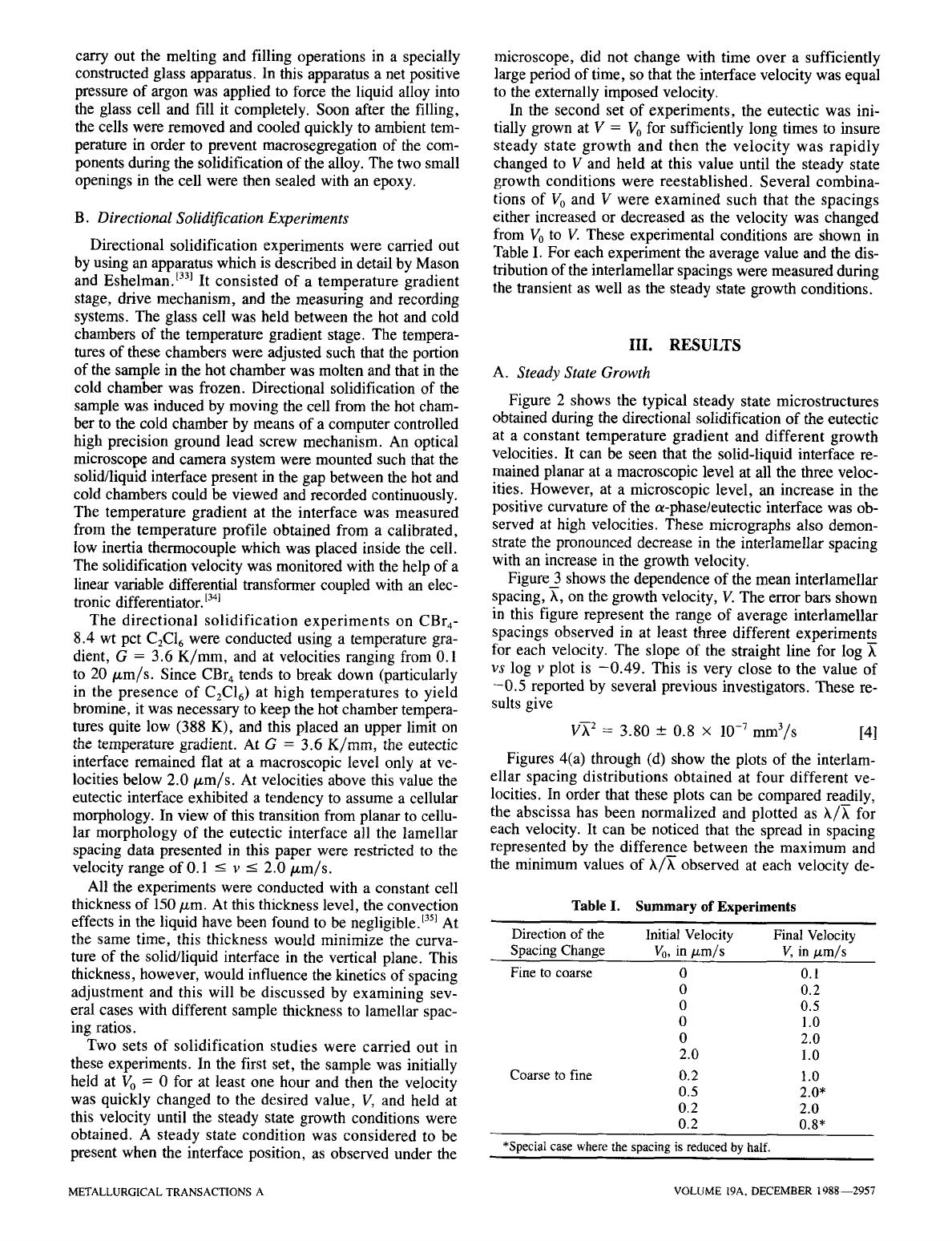

In the second set of experiments, the eutectic was ini-

tially grown at V = Vo for sufficiently long times to insure

steady state growth and then the velocity was rapidly

changed to V and held at this value until the steady state

growth conditions were reestablished. Several combina-

tions of V 0 and V were examined such that the spacings

either increased or decreased as the velocity was changed

from V0 to V. These experimental conditions are shown in

Table I. For each experiment the average value and the dis-

tribution of the interlamellar spacings were measured during

the transient as well as the steady state growth conditions.

III. RESULTS

A. Steady State Growth

Figure 2 shows the typical steady state microstructures

obtained during the directional solidification of the eutectic

at a constant temperature gradient and different growth

velocities. It can be seen that the solid-liquid interface re-

mained planar at a macroscopic level at all the three veloc-

ities. However, at a microscopic level, an increase in the

positive curvature of the a-phase/eutectic interface was ob-

served at high velocities. These micrographs also demon-

strate the pronounced decrease in the interlamellar spacing

with an increase in the growth velocity.

Figure3 shows the dependence of the mean interlamellar

spacing, h, on the growth velocity, V. The error bars shown

in this figure represent the range of average interlamellar

spacings observed in at least three different experiments

for each velocity. The slope of the straight line for log

vs

log v plot is -0.49. This is very close to the value of

-0.5 reported by several previous investigators. These re-

suits give

V~ 2 : 3.80 • 0.8 • 10 -7 mm3/s [4]

Figures 4(a) through (d) show the plots of the interlam-

ellar spacing distributions obtained at four different ve-

locities. In order that these plots can be compared readily,

the abscissa has been normalized and plotted as h/h for

each velocity. It can be noticed that the spread in spacing

represented by the difference between the maximum and

the minimum values of )~/h observed at each velocity de-

Table I. Summary of Experiments

Direction of the Initial Velocity Final Velocity

Spacing Change V0, in/zm/s V, in/zm/s

Fine to coarse 0 0.1

0 0.2

0 0.5

0 1.0

0 2.0

2.0 1.0

Coarse to fine 0.2 1.0

0.5 2.0*

0.2 2.0

0.2 0.8*

*Special case where the spacing is reduced by half.

METALLURGICAL TRANSACTIONS A VOLUME 19A. DECEMBER t988 2957

(a)

(b)

(c)

Fig. 2--Steady-state eutectic optical microstructures of directionally

solidified CBr4-8.4 wt pct CzCI6 alloys at different velocities: (a) V =

0.2/~rn/s, (b) V = 0.5/zm/s, and (c) V = 1.0/xm/s.

E

::L

I00

I0

.... I ........

I ' ' '

slope : -0.49

,,,,I , ,,

, ,,,,L ,

, ,

0.1 0 5 1.0 50

V,

/xrn/s

Fig. 3--Variation in the average interlamellar spacing with velocity.

creases with an increase in the velocity. Secondly, the plots

are distinctly asymmetric and have pronounced tails at

higher values of

h/-h. Thus it is necessary to measure the

following four experimentally observed spacing parameters

for each velocity: (i) the minimum observed spac:,g, h~an,

(ii) the maximum observed spacing, hmax, (iii) the average

spacing, h, and (iv) the most probable spacing, hmp. A

summary of these parameters, measured for different ve-

locities, is given in Table II.

Figure 5 shows the variations in hm~x and

hmi n

with the

growth velocity. Both the sets of data can be fitted with

straight lines of different slopes. The straight line corre-

sponding to the log

h~, vs log V plot has a slope of -0.50,

while that corresponding to log

hma x VS

log V has a slope

of -0.60.

B. Time Dependent Evolution of Eutectic Lamellae

In order to understand the distributions in the lamellar

spacings observed at steady state growth conditions, it is

essential to examine the manner in which the interlamellar

spacings evolve during the growth of the eutectic structure.

For this purpose, the interface was initially held at V = 0

for one hour and then the velocity was quickly increased to

the desired value. The microstructures obtained at and

slightly behind the solid-liquid interface were examined

from the very'early stages of growth and continued until

the steady state conditions were established. Figure 6 il-

lustrates typical microstructures observed as a function

of time at a velocity of 0.5/zm/s. When the cell was ini-

tially stationary, the solid/liquid interface was found to be

planar and the solid consisted of a single phase structure

only. When the imposed velocity was changed from zero to

0.5/zm/s, the single phase interface was found to move for

a few minutes before the eutectic lamellae were nucleated.

It is interesting to note that these lamellae were initially nu-

cleated at one edge of the cell and then the lamellar struc-

ture propagated very rapidly along the solid-liquid interface

toward the other edge (Figure 6(a)). Although the finely-

spaced, two-phase structure observed at early times was

rather ill-defined, it quickly developed into a periodic array

(Figure 6(b)). Subsequently, some of the lamellae were

eliminated and this led to a substantial increase in the inter-

lamellar spacing (Figures 6(c) and (d)). This elimination

process occurred quite randomly, leading to a continuous

increase in the interlamellar spacing with time. Figure 7

shows the increase in the average lamellar spacing with

time for different growth velocities. The important features

indicated in this graph are (i) the time required to 'nucleate'

the eutectic structure decreased with an increase in the ve-

locity, (ii) initially the lamellar spacing increased very

rapidly at all velocities but very soon the process of elimi-

nation of the lamellae became very slow, leading to a very

gradual increase in the lamellar spacing with time until

steady state spacings were established. If r is defined as

the time required to achieve an average spacing equal to

0.9 times the steady-state spacing, then ~" was found to de-

crease with the increase in velocity.

C. Dynamic Response of LameUar Spacings

It is now well established that the steady state primary

spacings of cellular and dendrite structures at any given ve-

locity are dependent on the previous solidification his-

tory. [36'37'381 In contrast, the cell or dendrite tip radii are

found to be independent of the path by which the final ve-

locity was reached. In view of this, it is germane to verify

whether the eutectic interlamellar spacings and their dis-

tribution obtained at any growth velocity are influenced

significantly if the initial velocity, V0, differs from zero.

2958--VOLUME 19A, DECEMBER 1988 METALLURGICAL TRANSACTIONS A

Fig. 4--Frequency distributions of the lamellar spacings observed at different velocities: (a) 0.2, (b) 0.5, (c) 1.0, and (d) 2.0/xm/s.

Accordingly, several directional solidification experiments

were designed and performed, as shown in Table I. In these

experiments, the sample cell was solidified at a specific

value of V0 mentioned above until the steady state growth

was achieved at that velocity. Then the cell velocity was

quickly changed from V0 to V and the directional solidifica-

tion was continued until steady state growth conditions

were re-established. The interlamellar spacings of the eu-

tectic structure were monitored continuously throughout

these experiments.

Table II. Experimental Values of Characteristic

Parameters for the Lamellar Spacing Distribution

V

(/~m/s) hm,, (/xm) hma x (/xm) X (/zm) hmp (/zm)

0.2 38.4 67.5 48.1 47.6

0.5 21.3 32.0 25.9 25.5

1.0 15.5 23.6 19.0 18.4

2.0 12.3 15.0 13.6 13.3

In one set of experiments, the steady-state eutectic spac-

ings were examined for V = 1/xm/s. For this study, three

different initial velocities, namely V0 = 0, 2.0, and 0.2/xm/s,

were chosen. The first two velocities will give a smaller

initial spacing and the third one a larger initial spacing

compared to the steady-state spacing at V = 1 /xm/s.

Figure 8(a) shows the changes in the average lamellar spac-

ing with time after the velocity was changed from V0 to

V = 1 /zm/s. The frequency distributions of the inter-

lamellar spacings for these three conditions are plotted in

Figure 8(b). Since a slightly larger average spacing was ob-

served for V0 = 0.2/xm/s, where the initial spacing was

larger, two additional experiments were carried out under

identical conditions to examine the reproducibility of these

results. Also, these experiments were extended over three

hours since the spacing was observed to drift to a smaller

value at an extremely slow rate. All these experiments showed

the spacing to remain slightly larger than that for the V0 =

0 case. The frequency distributions, however, were nearly

identical except that the peaks were slightly displaced to

METALLURGICAL TRANSACTIONS A VOLUME 19A, DECEMBER 1988~2959

I00

5O

E

::k

x"

10

_I I I~ I I I I I I I i I I I

"~ 9 X max

5 tl tl i i L i i i LL[ L I I

O. I 1.0 5.0

V, Fm/s

Fig. 5- Variations in the experimentally observed minimum and maxi-

mum lamellar spacings with different velocities.

(a)

(b)

60

50

40

2O

I I I I I I I I I I t "/z"

I0

=

-- -- -

V= 0 5/~m/s

9 • It ~VV = 2 p.m/s

I I I I I I I I 1

I//

O( I0 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 I00 I000

Fig. 7--Time evolution of the average interlamellar spacings during the

solidification of the eutectic at different velocities.

sequently, another set of experiments was carried out with

V0 = 0 and 0.2/im/s, and V = 2.0/zm/s. In this case,

d/-h

= 11. The results of these experiments are shown in

Figures 9(a) and 9(b). A small hysteresis effect was still

found to be present in this case.

If the hysteresis effect is present due to the kinetic diffi-

culty in creating new lamellae, one may not observe the

hysteresis effect if special values of V 0 and V were chosen

such that the initial spacing is twice the final steady-state

spacing. In this case, a reduction in spacing by half can

occur by nucleating fl-phase lamellae at the center of all

~-phase lamellae. Two different sets of such experiments

were carried out, as indicated in Table I. The results are

shown in Figures 10(a) and 10(b). Note that the spacing dis-

tribution curves superpose to some extent and the average

spacings do not differ significantly. It should be pointed out

that two different mechanisms for the creation of additional

lamellae were observed in these two experiments and these

mechanisms are described elsewhere in detail, t4~

(c)

(d)

Fig. 6--Evolution of larnellar structures during the directional solidifica-

tion

of the eutectic alloy at a velocity of 0.5/~m/s. The times measured

from the instant at which the velocity was changed from zero to 0.5/~m/s

are (a) II.33 rain, (b) II.67 rain, (c) 12.33 rain, and (d) 16 rain.

different average spacing values. In Figure 8(b), only one

distribution is shown to keep the clarity of the figure. The

small differences in the average spacings observed in our

experiments could be due to the fact that the spacing reduc-

tion on a finer scale requires faults which may not form in a

thin sample, t391 In our experiments the final value of

d/'h

was about 7.6, where d is the thickness of the sample. Con-

IV. DISCUSSION

We shall first discuss our results on interlamellar spac-

ings observed under steady-state conditions. Next, we shall

consider our dynamical experiments to examine the mecha-

nism which is responsible for the interlamellar spacing

selection.

The experimental results, for the case in which the veloc-

itywas increased from zero to the required value, show that

Vh 2 =

constant. The value of the constant is given in

Eq. [4]. In order to compare our steady-state results with

the theoretical model of Jackson and Hunt, the values of the

physical constants for the CBr4-C2C16 are required. The val-

ues off~ and f~ were determined from the micrographs

shown in Figure 2. We obtained f~ = 0.72, which is the

same result as that reported by Kaukler. t32] The values of

capillary constants and the contact angles have been mea-

sured by Kaukler, ml and they are given in Table III. The

only unknown value is the interdiffusion coefficient, D, in

the liquid phase.

Our experimental results for the minimum spacing

vs

ve-

locity show that

VX2mm

= 2.67 X 10 -7 mmS/s. [5]

2960--VOLUME 19A, DECEMBER 1988 METALLURGICAL TRANSACTIONS A

(a)

(a)

(b)

Fig. 8--(a) Changes in the average interlamellar spacings with time at a

growth velocity of 1 /zm/s for V0 = 0, 0.2, and 2.0 p.m/s. The times

were measured from the instant at which the velocity was changed from

V0 to V = 1 p.m/s. (b) Frequency distributions in the lamellar spacings

observed during steady state growth at V = 1 /.~m/s for different initial

velocities of 0, 0.2, and 2.0/.Lm/s.

Because of the transparent nature of the system, the elimi-

nation of spacings less than h m could be observed as a func-

tion of time. Thus, if we now consider only the observed

minimum spacing it should correspond to the smallest

stable spacing predicted by the eutectic stability theory, t~SJ

Thus, comparing Eqs. [2] and [5], we obtain

K2/K 1

=

2.67

x 10 -7

mm3/s. [6]

(b)

Fig. 9--(a) Changes in the average lamellar spacing with time, and

(b) the lamellar spacing distribution for the steady-state velocity of

2.0 p.m/s when the initial velocities were 0 and 0.2/xm/s.

Substituting the expressions for K~ and

K 2

from the Ap-

pendix, and using the values of the physical constants given

in Table III, the unknown value of D was determined to be

D = 8.27 • l0 -l~ mE/s [7]

With all the values of the physical constant known, we

can now compare our experimental results with the theo-

retical predictions of Jackson and Hunt, given by Eq. [1].

METALLURGICAL TRANSACTIONS A VOLUME 19A, DECEMBER 1988--2961

Table III. Numerical Values of the Physical

Constants for the CBr4-C2CI6 Eutectic System

f, = 0.72

0, = 65 deg

0t~ = 55 deg

m, = 1.482 K/wt pct

m s = 2.164 K/wt pct

C0= ll.lwtpct

F, = 8.0 • 10 -8 mK

F~ = 11.4 x 10 -8 mK

P(f,~

= 0.72) = 0.025

(a)

(b)

Fig. lO--(a) Changes in the average lamellar spacing with time for two

special cases in which the velocity was decreased by a factor of four to

change the spacing by half. The results for the increase in velocity from

the initial zero velocity are also shown for comparison. (b) The steady-

state lamellar spacing distribution for the two cases in which the final

steady-state velocity was the same.

Figure 11 shows the theoretical relationship between the

undercooling and the interlamellar spacing for different ve-

locities. The values of the minimum and the maximum

stable spacings, given by Eqs. [2] and [3], were also cal-

culated. These values are listed in Table IV, and they are

Fig. 11--Theoretically predicted variations in the interface undercool-

ing, AT, with the lamellar spacing, h, for different velocities. The experi-

mentally observed ranges of lamellar spacings at different velocities are

indicated by the hatched regions, and the mean values are shown by the

solid circle.

indicated on Figure 11 by the pairs of vertical arrows. The

experimentally observed range of spacing and the average

value of the spacings at each velocity are also shown in

the figure.

The average values of spacings are found to be much

closer to the minimum marginal stability values, and these

are significantly smaller than the maximum marginal stabil-

ity values. Furthermore, the distribution in spacings at a

given velocity is somewhat narrow at higher velocities, and

it becomes broader as the velocity is decreased. These re-

suits are similar to those reported by Jordan and Hunt t241 for

the Pb-Sn eutectic system.

All the experimentally observed spacings fall within the

stable region predicted by the Jackson-Hunt model. How-

ever, the experimental spacings constitute only a small

subset of the theoretically stable set of spacings. Further-

more, this subset lies very close to the minimum undercooling

value so that the deviation of the average spacing from that

corresponding to the minimum undercooling is small. Fig-

ure 12 shows the theoretical stable range of spacings as a

function of velocity. Experimental results are also plotted

for comparison. It should be noted that the line representing

the average spacing is nearly parallel to the theoretical line

for the minimum stable spacing. Consequently, the average

spacing, X, can be described as X

= ~)hm,

where ~b is a

constant, t251 The value of 4) = 1.2 describes the results in

the CBr4-C2C16 system.

The key point that we must address here is the experi-

mental observation of the selection of only a small band of

spacings from a larger stable band predicted by the theory.

Table IV. The Theoretical Values of VA 2 and

VA 2, as Predicted by the Jackson-Hunt Theory

f, Vh2

(~m3/s)

Vh~

(~m3/s)

0.5 194.5 2170

0.72 284 --

0.9 1072 2222

2962--VOLUME 19A, DECEMBER 1988 METALLURGICAL TRANSACTIONS A

Fig. 12--A comparison of the experimental results on the interlamellar

spacing variation with velocity with the theoretical values for the two

marginally stable spacings.

Specifically, we would like to examine the reason for the

formation of a range of spacings and understand why this

range of spacings lies close to the minimum undercooling

value. Both these aspects are interrelated, and they will

now be discussed by examining the results of our dynami-

cal studies.

The experiments discussed above had a zero initial ve-

locity, which was then increased rapidly to the desired

value, V. The initial spacing, dictated by the nucleation

considerations, was extremely fine, and it increased with

time, as shown in Figure 7. This coarsening continued until

the spacing entered the stable region. Since the spacing ap-

proached the stable region from h < h,,, they became

stable just above the minimum undercooling point. Once

the lamella with h <

h m

is eliminated, the local spacing

that is created would be larger than

h m .

Thus a range of

spacings less than

h m

will give rise to a range of spacings

above

h m

as the lamellar terminations occur.

The results of dynamical studies in which the initial spac-

ing was larger than the final value will now be discussed.

These studies show that the spacing decreases rapidly first,

but then it approaches the steady-state value at very low

rates. Figure 8(a) shows that the final spacing change is sig-

nificantly slower so that the eutectic spacing does not attain

a constant value even after a long time. This very slow rate

of spacing reduction gives an apparent hysteresis effect

which, we believe, is due to the finite thickness of our sam-

pies. Experimental studies for the special case of spacing

reduction by half show that the average spacing approaches

the same distribution irrespective of the direction in which

the spacing change occurred. Since the mechanisms of

spacing reduction were found to be the same for both cases,

we conclude that the small hysteresis effect observed in

these experiments is due to the small ratio of the sample

thickness to the lamellar spacing.

In order to examine the effect of sample thickness on the

eutectic spacing change, experiments were carried out with

larger sample thickness values. In these experiments sev-

eral grains of eutectics were observed which resulted in a

poor resolution of structure so that it was difficult to mea-

sure the spacing precisely. In order to check the effect of

sample thickness, an analogous experiment has been car-

ded out in a metallic system t41] which shows identical spac-

ing distributions irrespective of whether the initial spacing

was larger or smaller than the steady-state spacing.

One of the aims of this study was to examine the range

of stable spacings discussed by Jackson and Hunt.IT1 All

our experimental results show that the actual spacing dis-

tribution is always close to the hm value. Figure 13 sche-

matically summarizes experimental observations. The open

points represent the initial average spacings, whereas the

filled points show the corresponding final average spac-

ings. It is observed that all the final average spacings were

always slightly above the minimum stable spacing value.

Furthermore, the results of the velocity change from 0.5 to

2.0 ~m/s, represented schematically in Figure 13 as open

and filled circles, show that the initial spacing distribution

for this case was within the stable zone of the final ve-

locity as predicted by the Jackson-Hunt criterion. Thus, if

the theoretical range of stable spacings is valid, then no

change in spacing would be expected. However, as seen in

Figure 10(a), a significant decrease in spacing occurred as

the velocity was changed. Thus, the hM value discussed by

Jackson and Hunt I7] is significantly larger than the actual

hM

value exhibited by the system. We thus conclude that the

criterion of infinite interface slope of the major phase is not

a proper criterion to predict the largest stable spacing. It is

quite probable that the interface becomes unstable when the

slope is finite but exceeds some critical value. A similar

conclusion has been reached by Magnin and

Kurz [26]

for the

growth of irregular eutectics. They showed that the spacing

becomes unstable when the minor phase lamella develops

a small depression whose center is slightly above the line

joining the two triple point junctions of that lamella. De-

tailed experimental studies in the CBr4-C2C16 system by the

authors I4~ have also shown that the larger eutectic spacings

become unstable before the slope of the major phase inter-

face with liquid becomes infinity. Thus, a more rigorous

stability analysis is still needed to characterize precisely the

value of hM.

Fig. 13--A schematic diagram which summarizes the results of the dy-

namical experiments. Various initial spacings are represented by the open

points, and the final spacings are given by the corresponding filled points.

METALLURGICAL TRANSACTIONS A VOLUME 19A, DECEMBER 1988--2963

V. CONCLUSIONS

The theoretical model of eutectic growth, based on diffu-

sional considerations, shows that the lamellar structures

have infinite solutions for a given velocity. It is now well-

established in the literature that, of all these solutions, only

a band of spacings is stable with respect to fluctuations in

the shape of the interface (or in the local spacings). Experi-

mental studies on the variation in the average eutectic spac-

ing with velocity show that this average value lies very

close to the minimum undercooling value. Therefore, it has

been suggested that the eutectic spacing is unique at a given

velocity and this unique value is governed by the minimum

undercooling criterion. Since there is no fundamental basis

for such an optimization principle, we carried out critical

experiments to determine carefully the spacing selection

mechanisms. This study was partly influenced by the ex-

perimental studies of Jordan and Hunt who showed that the

eutectic spacing is not unique but that a band of spacings

exists at a given velocity. We have confirmed their results

in the CBr4-C2C16 system. Furthermore, we have examined

the distribution of spacings at different velocities. We have

shown that average spacing is closer to the minimum under-

cooling value. It is also shown that such spacing distribu-

tions, for a sample of large thickness, are independent of

the direction of the spacing change for a given final veloc-

ity. Dynamical experiments were carried out in which the

initial spacings were larger than the steady-state spacing,

but were within the stable range predicted by Jackson-

Hunt. I71 A sharp reduction in spacing was observed which

shows that the stable range of eutectic spacings is signifi-

cantly smaller than that discussed by Jackson and Hunt.

APPENDIX

Values of system parameters in the Jackson-Hunt model

The values of the constants Kl and K2, in Eq. [ 1 ], are

given by

K, = -~Co P /f~,ft3 O ,

and

t[-F~

Sin 0~ F0 Sin 0p]

K2 = 2~ - --- +

L f~m~ f~m~ I

where 1/m = (1/m~) + (1/m~), in which m~ and m~ are

the magnitudes of the liquidus slopes for the oL and/3

phases, respectively, at the eutectic temperature, f~ and f0

are the volume fractions of the a and 13 phases, respec-

tively. D is the interdiffusion coefficient in liquid, Co the

equilibrium concentration difference between the/3 and the

o~ phase at the eutectic temperature, F, and F~ are the capil-

lary coefficients, and 0~ and 00 are the equilibrium angles

with respect to the planar interface at the triple point junc-

tion. P is a function of volume fraction, and its value is

given by P = E~=l 1/(n'lr) 3 Sin2(mrf~).

For the largest stable spacing, h M, given by Eq. [3], the

value of the constant K3 is given by:/vl

K 3 = a(1 + b sin 0)~:',

when s c' = F~ Sin O,~D/PCom,~ and the constants a and b

are functions of the volume fractions of the two phases.

Table IV in the text shows that the numerical value of K3 is

not very sensitive to the volume fraction changes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was carried out at Ames Laboratory which is

operated for the United States Department of Energy by

Iowa State University under contract no. W-7405-ENG-82.

This work was supported by the Office of Basic Energy

Sciences, Division of Materials Sciences. Appreciation is

expressed to W. Kurz and J.T. Mason for many valuable

discussions and for their comments on the manuscript.

REFERENCES

1. R. Elliott:

Eutectic Solidification Processing,

Butterworth's, Lon-

don, 1983.

2. C.A. Adam: in

Science and Technology of Undercooled Melt, P. R.

Sahm, H. Jones, and C. M. Adam, eds., Martinus Nijhoff, Dedrecht,

1986.

3. W.H. Brandt:

J. Appl. Phys.,

1945, vol. 16, p. 139.

4. C. Zener:

Trans. AIME,

1946, vol. 167, p. 550.

5. M. Hillert:

Jernkontorets Ann.,

1960, vol. 144, p. 520.

6. W.A. Tiller:

Liquid Metals and Solidification,

ASM, Metals Park,

OH, 1958, p. 276.

7. K.A. Jackson and J.D. Hunt:

Trans. AIME,

1966, vol. 236,

p. 1129.

8. E R. Mollard and M.C. Flemings:

Trans. AIME,

1967, vol. 239,

p. 1526.

9. S. Strassler and W. R. Schneider:

Phys. Cond. Matter,

1974, vol. 17,

p. 153.

10. D.T.J. Hurle and E. Jakeman:

J. Cryst. Growth,

1968, vol. 3,

p. 574.

11. H.E. Cline:

J. Appl. Phys.,

1982, vol. 53, p. 5898; 1968, vol. 242,

p. 1613.

12. G.E. Nash:

J. Cryst. Growth,

1977, vol. 38, p. 155.

13. R.E Sekerka:

J. Cryst. Growth,

1971, vol. 10, p. 239.

14. J.S. Langer:

Phys. Rev. Lett.,

1980, vol. 44, p. 1023.

15. V. Datye and J. S. Langer:

Phys. Rev. B,

1981, vol. 24, p. 4155.

16. V. Datye, R. Mathur, and J. S. Langer:

J. Stat. Phys.,

1982, vol. 29,

p. 1.

17. D. Meiron:

Phys. Rev. A,

1986, vol. 33, p. 2704.

18. J.S. Langer and D. C. Hong:

Phys. Rev. A,

1986, vol. 34, p. 1462.

19. D.A. Kessler and H. Levine:

Phys. Rev. A,

1987, vol. 36, p. 4123.

20. W. Kurz and P. R. Sahm:

Gerichtet Erstarrte Eutektische Werkstoffe,

Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 1975.

21. M. Tassa and J. D. Hunt:

J. Cryst. Growth,

1976, vol. 34, p. 38.

22. J.N. Clark and R. Elliott:

Met. Sci. J.,

1976, vol. 10, p. 101.

23. J.N. Clark and R. Elliott:

Metall. Trans. A,

1976, vol. 7A, p. 1197.

24. R.M. Jordan and J. D. Hunt:

Metall. Trans.,

1971, vol. 2, p. 3401.

25. D.J. Fisher and W. Kurz:

Acta Metall.,

1980, vol. 28, p. 777.

26. P. Magnin and W. Kurz:

Acta Metall.,

1987, vol. 35, p. 1119.

27. H. Jones and W. Kurz:

Z. Metallk.,

1981, vol. 72, p. 792.

28. D.J. Fisher and W. Kurz: in

Solidification and Casting of Metals,

Metals Soc., London, 1978, p. 57.

29. J.D. Hunt and K. A. Jackson:

Trans. AIME,

1966, vol. 236, p. 843.

30. H.S. Chen and K. A. Jackson:

J. Cryst. Growth,

1971, vol. 8,

p. 184.

31. W.F. Kaukler and J.W. Rutter:

Mat. Sci. Engg.,

1984, vol. 65,

p. LI.

32. W. E Kaukler: Ph.D. Thesis, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON,

Canada, 1981.

33. J.T. Mason and M. A. Eshelman: IS-4906, Ames Laboratory, Ames,

IA, 1986.

34. M.A. Eshelman: Ph.D. Thesis, Iowa State University, Ames, IA,

1987.

35. K. Somboonsuk: Ph.D. Thesis, Iowa State University, Ames, IA,

1984.

36. K. Somboonsuk and R. Trivedi:

Acta Metall.,

1985, vol. 33,

p. 1051.

37. M.A. Eshelman, V. Seetharaman, and R. Trivedi:

Acta Metall.,

1988, vol. 36, p. 1165.

38. V. Seetharaman, M.A. Eshelman, and R. Trivedi:

Acta Metall.,

1988, vol. 36, p. 1175.

39. H.E. Cline:

Mat. Sci. Eng.,

1984, vol. 65, p. 93.

40. V. Seetharaman and R. Trivedi: in

Solidification Processing of Eu-

tectic Alloys,

D. Stefanescu and G.J. Abbaschian, eds., AIME,

Warrendale, PA, 1988.

41. R. Trivedi, J.T. Mason, and W. Kurz: unpublished work. 1987.

2964--VOLUME 19A, DECEMBER 1988 METALLURGICAL TRANSACTIONS A