Article

DOI: 10.1557/jmr.2019.299

ADVANCES IN BATTERY TECHNOLOGY: MATERIAL INNOVATIONS IN DESIGN AND FABRICATION

Annealing of LiCoO

2

films on flexiblestainlesssteel for thin

film lithium batteries

Yibo Ma

1

, Mu Chen

1

, Yue Yan

1,a)

, Youxiu Wei

1

, Weiming Liu

1

, Xiaofeng Zhang

1

, Jiaming Li

1

,

Ziyi Fu

1

, Jiuyong Li

1

, Xuan Zhang

1

1

Beijing Engineering Research Center of Advanced Structural Transparencies for the Modern Traffic System, Beijing Institute of Aeronautical Materials,

Beijing 100095, China

a)

Received: 27 June 2019; accepted: 18 September 2019

The LiCoO

2

films were directly deposited on stainless steel (SS) using medium-frequency magnetron sputtering,

and the effects of annealing paramete rs, such as ambiences, temperatures, holding times, and heating rates,

were systematically compared based on surface morphologies, crystal structures, and electrochemical

properties. The results demonstrate that an aerobic atmosphere with 3.5 Pa is the most important parameter to

maintain the performance of LiCoO

2

films. The in fluence of the annealing temperature (>550 °C) ranks second

because the formed (101) or (104) planes of LiCoO

2

facilitate Li

+

migration. A short holding time of 20 min and

a moderate heating rate of 3 °C/min are selected to reduce the oxidation or inter-diffusion between the LiCoO

2

films and the SS substrate. Finally, the optimal annealing process is confirmed and corresponds to the initial

discharge capacity of 37.56 lA h/(cm

2

lm) and the capacity retention of 83.81% at the 50th cycle.

Introduction

Researchers now pay more attention to all-solid-state thin film

lithium batteries (TFLBs) due to their potential applications

such as main power in identification cards, metal–oxide–

semiconductors, and flexible electronic paper displays [1].

The fabrication of LiCoO

2

films as cathodes in TFLBs is

a successful choice due to their excellent electrochemical

properties and maturity of manufacturing [2]. Compared to

the traditional hard substrates, such as Si or mica, TFLBs on

stainless steel (SS) are flexible; that is, they can be charged/

discharged in a bending state [3] and, thus, can be applied in

wearable devices [4, 5]. Since the as-grown LiCoO

2

films

prepared by magnetron sputtering (MS) at room temperature

are in an amorphous state, a post-annealing process is indispens-

able to obtain crystalline LiCoO

2

. Traditional post-annealing

methods for LiCoO

2

films include tube furnace heating [6], rapid

thermal annealing [7, 8, 9, 10, 11], in situ heating [12], two-step

heating [13], and plasma-assisted treatment [14, 15]. In this

article, annealing is performed in the tube furnace due to the

uniform temperature distribution and low cost.

The deposition of LiCoO

2

films by MS is always in an

anoxic state; in order to keep the ideal stoichiometric ratio of

Co:O and an ideal layered structure, an aerobic environment is

required in the post-annealing process. But the SS substrate is

inevitably oxidized and the oxidation layer formed on both

sides of SS increases the battery internal resistance [16, 17, 18].

These oxidation layers need to be polished before battery

assembly. However, the shortcomings do not obscure the

potential of SS as a substrate. SS can directly act as current

collectors, and thereby simplify the manufacturing process and

reduce the material cost [19]. Compared with flexible sub-

strates such as Cu or Al foil, SS has better chemical stability, is

more suitable for annealing at a high temperature, and is easily

compatible with flexible electronic devices [20, 21].

Failures in LiCoO

2

films, such as delaminations, wrinkles,

or cracks, often occur after post-annealing. The cracks cause

short circuits when the solid electrolyte and lithium anode are

deposited subsequently during TFLB fabrication. So it is

obvious to optimize annealing parameters of the LiCoO

2

films

to improve the discharge capacity or cycle life of TFLBs. In

addition, some annealing works on LiCoO

2

in Table I in-

troduce the following four annealing parameters [6, 8, 21, 22,

23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28]. First, both pure oxygen and air

environments are preferred annealing ambiences. Second,

a low annealing temperature (,600 °C) can reduce film cracks

or by-products; however, insufficient heating (,400 °C) leads

ª Materials Research Society 2019 cambridge.org/JMR 1

j Journal of Materials Research j www.mrs.org/jmr

FOCUS ISSUE

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. La Trobe University, on 27 Oct 2019 at 05:00:57, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1557/jmr.2019.299

to poor crystallization, which results in poor cycle ability. Last,

a time-saving method is adopted to reduce the interface side

reaction for holding time and heating rate. All of the articles

mentioned in Table I is beneficial to the optimal annealing of

LiCoO

2

films on flexible SS. However, each article only

discusses one annealing parameter, while a reasonable anneal-

ing process considering the combined effects of four annealing

parameters is performed here.

This article introduces a systematic investigation of the

effects of the post-annealing process on LiCoO

2

films grown by

MS. The effects of annealing ambiences, temperatures, holding

times, and heating rates are compared in terms of composi-

tions, surface morphologies, crystal structures, and charge/

discharge performances. Then, an optimum annealing process

for LiCoO

2

films is obtained and this work provides compre-

hensive support for the annealing of LiCoO

2

films.

Results and discussion

Annealing atmosphere

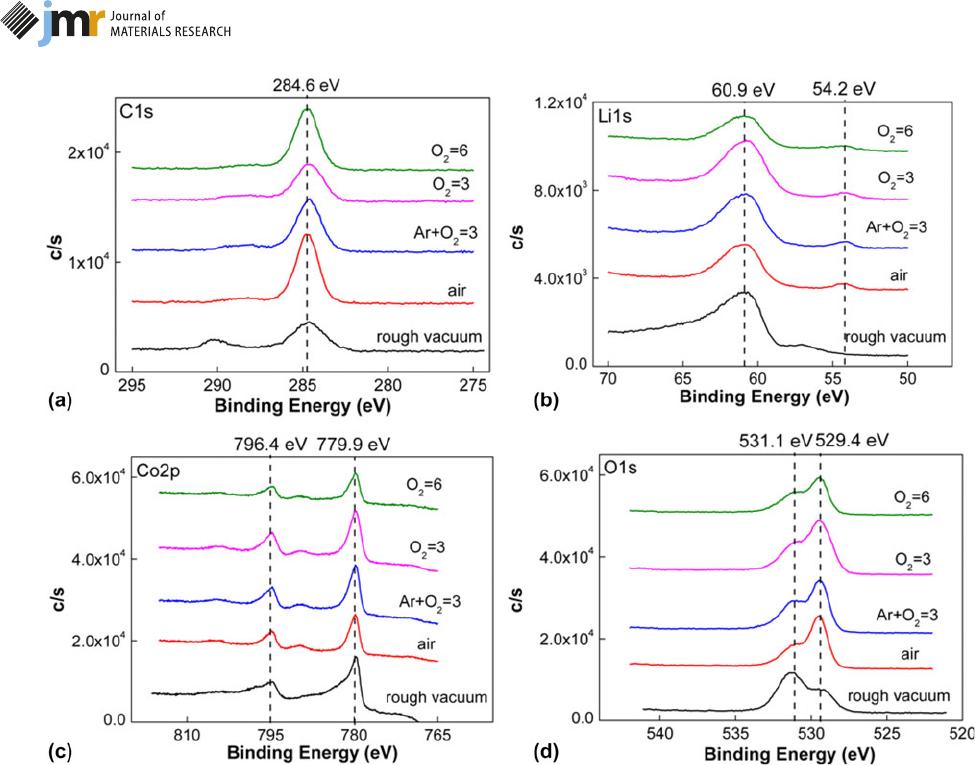

The compositions of these LiCoO

2

films ann ealed u nder

different atmospheres are detected by X-ray photoelectron

spectroscopy (XPS). The contaminated carbon (C 1s,284.8

eV) in Fig. 1(a) is used to c alibrate the positions of other

elements. In Fig. 1(b), Li signals at the binding en ergy of 60.9

eV represent LiC

6

[27], which is a compound with surface-

contaminated carbon; this p roduct exists in other annealing

conditions too. However, Li signals under rough v acuum exist

in the form of Li

2

CO

3

at 55.6 eV, and Li

2

CO

3

may be formed

by the reaction between Li

2

O precipitated from film and H

2

O

and CO

2

in air. The other Li signals are LiOH at 54.2 eV,

formed by the reaction between Li

2

Oprecipitatedfrom

LiCoO

2

and H

2

O in air [24]. Figure 1(c) expresses the same

Co s ignal s of Co 2p

3/2

(BE 5 77 9.9 eV) and Co 2p

1/2

(BE 5

796.4 eV) in any an nealing atmosphere, and the correspond-

ing products are Co

3

O

4

and CoO impurity phases [29, 30].

The peaks of O 1s signals for different samples are also the

same in Fig. 1(d). One peak corresponds to LiCoO

2

at 531.1

eVandtheotherisCo

3

O

4

at 529.4 eV, with the removal of Li

element d uring annealing, and th e signal of Co

3

O

4

increases

[31, 32]

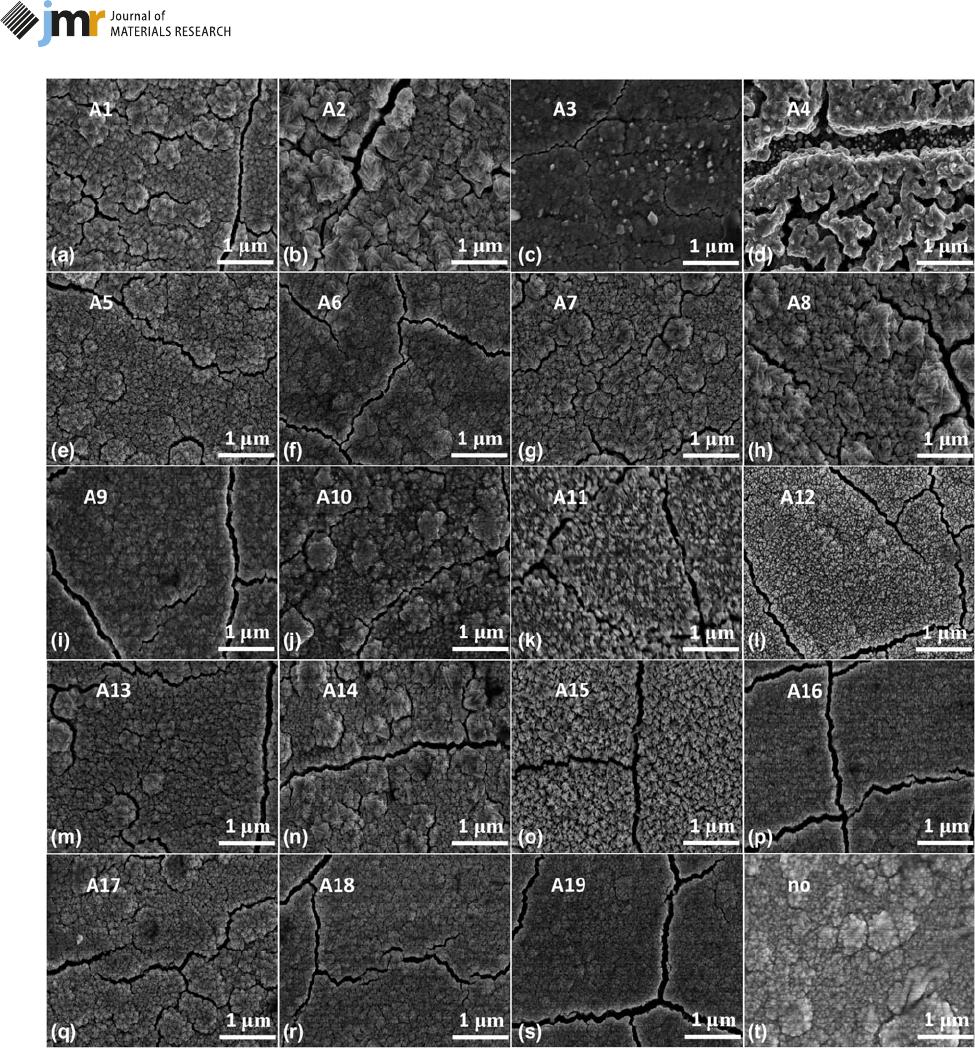

The SEM images of the annealed LiCoO

2

films are shown

in Fig. 2. The surface of any annealed LiCoO

2

films [as shown

in Figs. 2(a)–2(s)] exhibits the network cracks, and the

average width of the crack is ;100 n m. Particularly, sample

A4 annealed under pure vacuum [Fig. 2(d)] expresses more

obvious c rack topography with a width more than ;400 nm.

In fact, all the cracks are introduced by the thermal stress

(r

thermal

) during the cooling down process, and r

thermal

is

calculated by the difference in thermal expansion coefficient

between the LiCoO

2

film and SS according to formula (1) [33,

34, 35]. Once the thermal stress exceeds the load limitation,

more interface cracks are generated to release the excessive

thermal stress [21, 36, 37]. For example, r

thermal

in the

LiCoO

2

film annealed at 650 ° C is equal to 0.78 GPa

(compressive stress); the film’ sstressis0.18GPalargerthan

that of the sample annealed at 500 °C. Especially, the un-

annealed film is uniformly continuous without any cracks, but

several large particles with diameter of ;500 nm distribute on

the surface according to Fig. 2(t). Moreover, Fig. 3 shows

a cross-sectional image of the LiCoO

2

films on SS; the

annealed LiCoO

2

films possess the traditional columnar

crystal structure and the film thickness is ;1.09 lm, consistent

with the measured thickness of 1.1 lm using a profilerTencorP

7, KLA (keeping looking ahead) Co., Chandler, Arizona.

r

thermal

¼ Y

LiCoO

2

=1 m

LiCoO

2

a

LiCoO

2

a

SS

ðÞDT ; ð1Þ

where the thermal expansion coefficient of LiCoO

2

a

LiCoO

2

ðÞis

1.3 10

5

K

1

, a

SS

is 1.8 10

5

K

1

, and Young’s modulus

Y

LiCoO

2

ðÞand Poisson’s ratio m

LiCoO

2

ðÞof LiCoO

2

are 191 GPa

and 0.24, respectively [38].

All the LiCoO

2

films annealed in pure oxygen ambiences,

such as A1, A2, and A5 in Figs. 2(a), 2(b), and 2(e), form

triangular-shaped grains and the average grain size is

;100 nm. This triangular shape is probably due to the strong

(001) preferential plane [39]. For the LiCoO

2

film annealed

under air (A3) in Fig. 2(c), grains are uniformly granular

shaped and the average size also approaches 100 nm. However,

sample A4 annealed in rough vacuum shows loosely packed

worm-like particles and large amounts of voids or cracks

[Fig. 2(d)]. These are not typical morphologies of the crystal-

lized LiCoO

2

structure.

TABLE I: Previous annealing parameters for LiCoO

2

thin films.

Annealing parameters Type or range Function Reference

Annealing atmosphere Ar/O

2

mixture, air, O

2

, Ar,

rough vacuum

Influencing the film composition. Pure O

2

—better LiCoO

2

performance;

pure Ar—dehydrated LiCoO

2

; Air—poor LiCoO

2

performance

[3, 13, 21]

Annealing temperature 400–750 °C T . 700 °C—Li is missing, Co

3

O

4

impurity phase, and a serious side

reaction occurs; T , 400 °C— a spinel type (LT-LiCoO

2

);

T 5 550 °C–600 °C—an ideal layered structure

[13, 14, 15, 16]

Holding time 0–120 min Determining the crystal structure [6, 17]

Heating rate 1–600 °C/min Controlling the interface side reactions [5, 18, 19]

Article

ª Materials Research Society 2019 cambridge.org/JMR 2

j Journal of Materials Research j www.mrs.org/jmr

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. La Trobe University, on 27 Oct 2019 at 05:00:57, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1557/jmr.2019.299

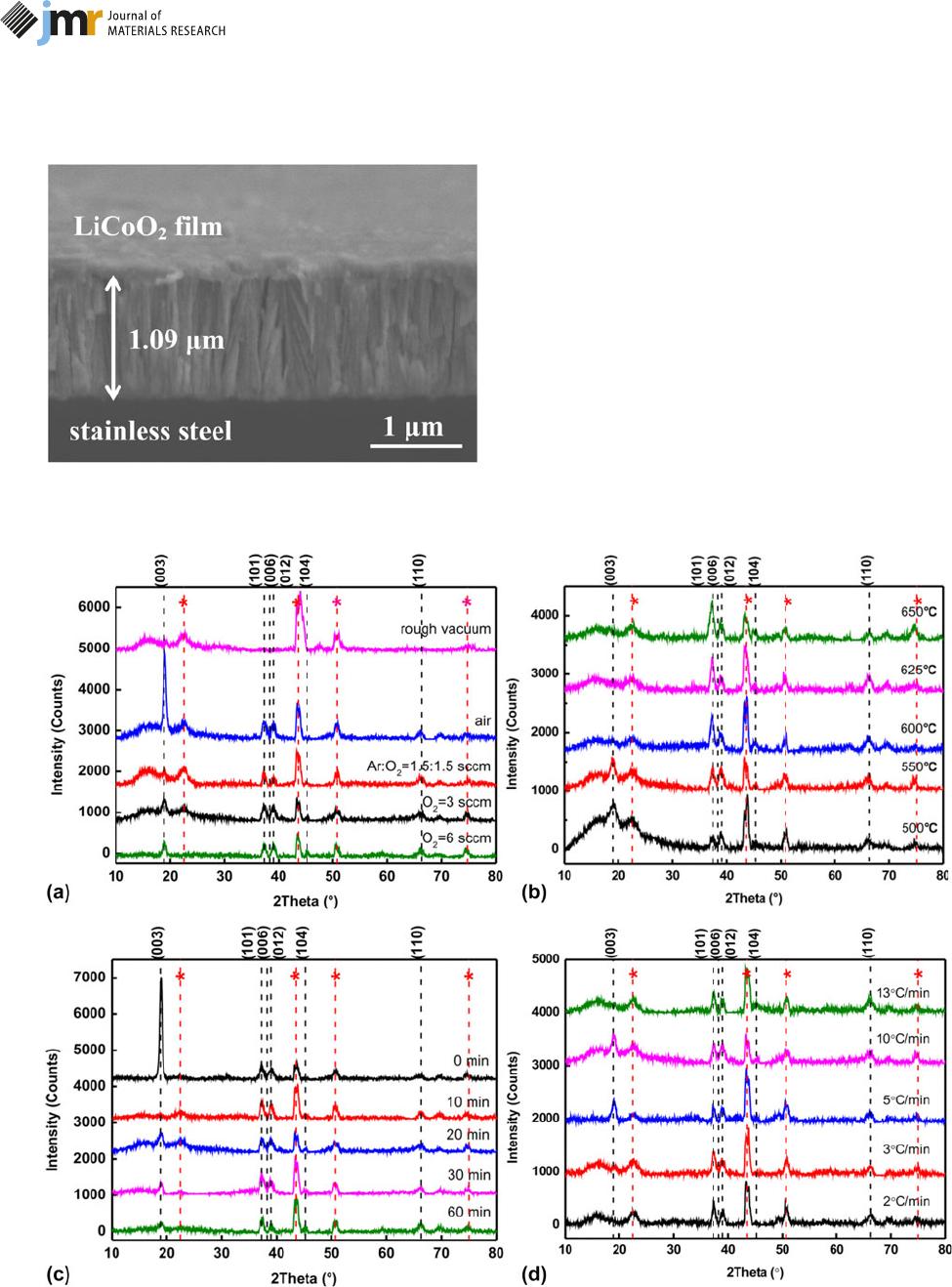

Figure 4(a) presents the XRD patterns of the LiCoO

2

films

annealed at various atmospheres. The diffraction peaks are

located at 2h 5 19.2°, 37.3°, 39.0°, 45.3°, and 66.1°, corre-

sponding to the (003), (101), (012), (104), and (110) crystal

planes of the LiCoO

2

film [7]. Here, (003) stands for a layered

structure and (104) identifies a basic unit Co–O–Co in the

layered LiCoO

2

structure. Additional four positions particularly

marked by the asterisk (*) stand for MoNi

4

(PDF 65-5480)

from SS during the annealing process [21]. The sample

annealed in air shows (003) preferred plane especially; the

other samples are polycrystalline. The relative intensity of the

(003) peak gradually increases and the intensity of the (104)

peak begins to appear with the enhancement of O

2

content,

which declares that the oxygen-rich environment contributes to

LiCoO

2

crystallization. Due to the formation of oxygen

vacancies during the annealing process, the increase in oxygen

vacancies is against the formation of dense (003) grains, but

tends to form (101) and (104) grains. So the efficient oxygen

content in the annealing environment is necessary because

excess oxygen atoms on the LiCoO

2

surface are first taken away

and then a large number of oxygen atoms at the grain

boundary position are driven into the film surface to form an

oxide layer, causing an increase in oxygen vacancies inside the

films.

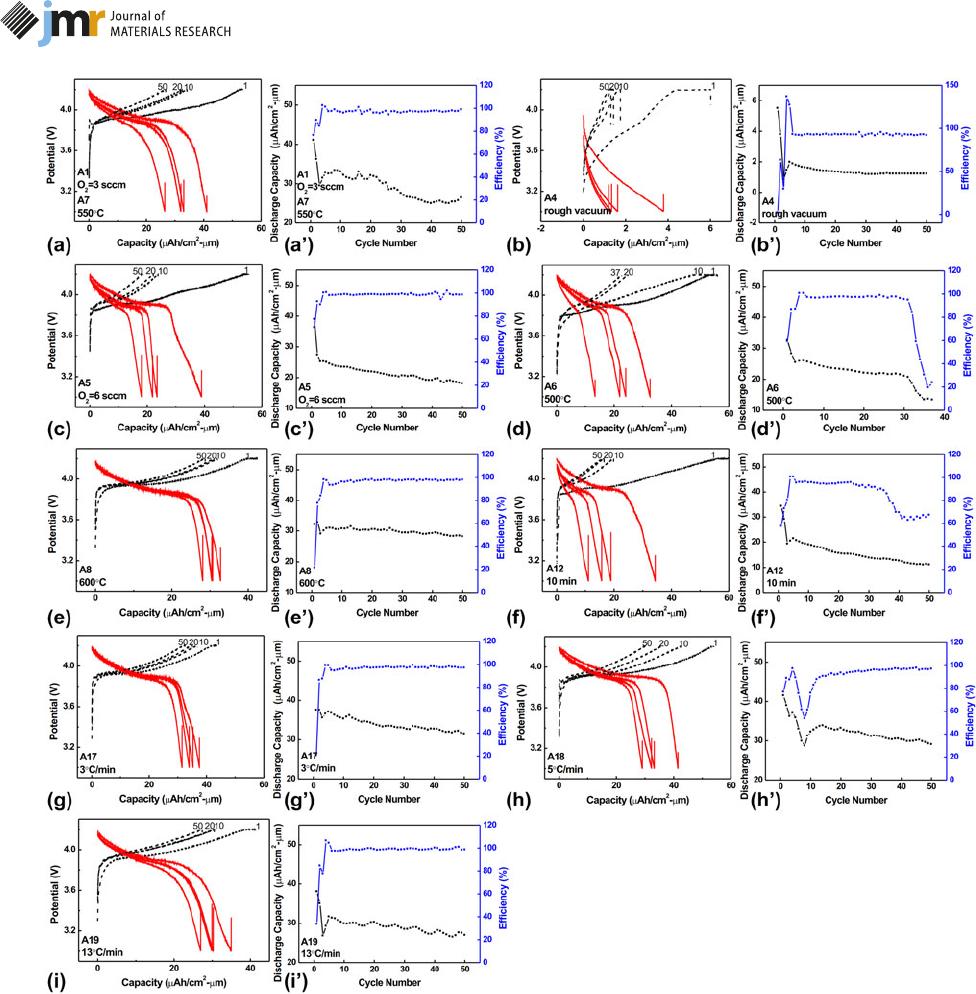

It should be mentioned that the initial open-circuit

potential is ;2.8 V when the LiCoO

2

half-cells are assembled.

Charge/discharge curves and cycle performance are presented

in Fig. 5. The annealed LiCoO

2

films show the same trend: the

discharge capacity decays abruptly during the initial four cycles

and then decreases slowly, which is testified by the columbic

efficiency values. In the case of two samples annealed in O

2

5 3

sccm and O

2

5 6 sccm, the discharge curves in Figs. 5(a) and

5(c) show a typical discharge platform in the range of 3.8–4.0

V, and the discharge capacity decreases with ;0.1 lA h/(cm

2

lm) per cycle as shown in Figs. 5(a9) and 5(c9), the sample

treated with O

2

5 3 sccm has the 1st discharge capacity of

41.06 lA h/(cm

2

lm) and the 50th capacity retention ratio of

64.34%, and the sample treated with O

2

5 6 sccm has the

corresponding values of 38.96 lA h/(cm

2

lm) and 46.25%.

However, the discharge curve slopes down without any

plateaus in Fig. 5(b) for the sample annealed under rough

vacuum, its 1st discharge capacity is only 5.51 lA h/(cm

2

lm),

Figure 1: Surface composition of LiCoO

2

films under different annealing atmospheres: (a) C 1s, (b) Li 1s, (c) Co 2p, and (d) O 1s signals. Atmosphere types are

added next to the curves.

Article

ª Materials Research Society 2019 cambridge.org/JMR 3

j Journal of Materials Research j www.mrs.org/jmr

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. La Trobe University, on 27 Oct 2019 at 05:00:57, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1557/jmr.2019.299

and the 50th discharge capacity is 1.21 lAh/(cm

2

lm); this low

capacity can be explained by decomposing of the formed LiCoO

2

to an Li-deficient phase (Li

0.62

CoO

2

) or to the spinel hetero-

phase due to the lack of oxygen during annealing. The presence

of the above phases makes LiCoO

2

capacity to attenuate fast

during charging in a wide range of voltages (3.6–4.2 V) [24].

Furthermore, the LiCoO

2

films annealed in Ar/O

2

mixed gas or

air atmosphere are unable to charge to 4.2 V because an unstable

secondary phase of LiCoO

2

forms and this disturbs Li

1

migration. In addition, the formation of the Co

3

O

4

impurity

phase during the annealing process also deteriorates the electro-

chemical properties of LiCoO

2

[22, 40]. According to the above

charge/discharge curves, the annealing atmosphere of pure O

2

is

confirmed prior to the other process parameters.

Annealing temperature (T)

The effects of different T on the surface topographies are

shown in Figs. 2(f)–2(j). Sample A6 that annealed at 500 °C

contains uniformly granular grains with a small size of ;30 nm

Figure 2: SEM images of the LiCoO

2

films annealed with different atmospheres, temperatures, holding times, and heating rates from (a) to (s), and (t) represents

an un-annealed LiCoO

2

film.

Article

ª Materials Research Society 2019 cambridge.org/JMR 4

j Journal of Materials Research j www.mrs.org/jmr

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. La Trobe University, on 27 Oct 2019 at 05:00:57, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1557/jmr.2019.299

as shown in Fig. 2(f); LiCoO

2

grains become triangular once

the T reaches 550 °C and the corresponding grain size increases

to ;50 nm as shown in Fig. 2(g). Moreover, the average

LiCoO

2

grain size increases by ;35 nm for every 50 °C

increment between 550 and 650 °C. Some micro-cracks with

a length of 200–500 nm appear as the T increases. Thermal

stress in sample A6 (500 °C) is compressive and the stress value

is 0.66 GPa, 0.13 GPa less than that in A10 (650 °C). This

excessive stress may be released in the form of micro-cracks.

Figure 4(b) presents the XRD diagrams of the LiCoO

2

films

annealed at different T.Allofthesefilms are crystallized and

a hexagonal phase with a space group of R

3m is obtained. The

(003) plane disappears when the T exceeds 550 °C, while the other

peaks exist in the range of 500–650 °C. In addition, the intensities

of (101) and (104) peaks relative to substrate signals increase

slightly with the elevated T, which indicates the LiCoO

2

films

tend to be crystallized in (101) and (104) facets and the

crystallization degree becomes better on a SS substrate [12,

19]. The preferred textures block Li

1

diffusion s ince no Li

1

channel is accessible on the film surface [41]. Especially, the

Figure 3: SEM image of the fractured cross section of the LiCoO

2

film grown

on SS substrate, annealed at 550 °C under a pure oxygen environment.

Figure 4: XRD patterns of LiCo O

2

films annealed at different (a) annealing atmospheres, (b) temperatures, (c) holding times, and (d) heating rates. Crystal patterns

in LiCoO

2

are marked with the black dashed line and substrate signals are marked by the red dotted line. Different annealing conditions are added next to the

curves.

Article

ª Materials Research Society 2019 cambridge.org/JMR 5

j Journal of Materials Research j www.mrs.org/jmr

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. La Trobe University, on 27 Oct 2019 at 05:00:57, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1557/jmr.2019.299

sample annealed at 650 °C shows a slight splitting at the (104)

peak position, which indirectly reflects that the grain is

distorted here, and the Li

1

lacking phase may occur due to

severe evaporation of Li

1

atoms when T is too high [21, 29].

Moreover, Jeon et al. point out that the interface side reaction

between LiCoO

2

films and SS occurs using XRD di agrams of

different T.WhenT increases to 700 °C, the reflections of

Fe

2

O

3

,Fe

3

O

4

,andCoCrO

4

compounds are observed [12, 21].

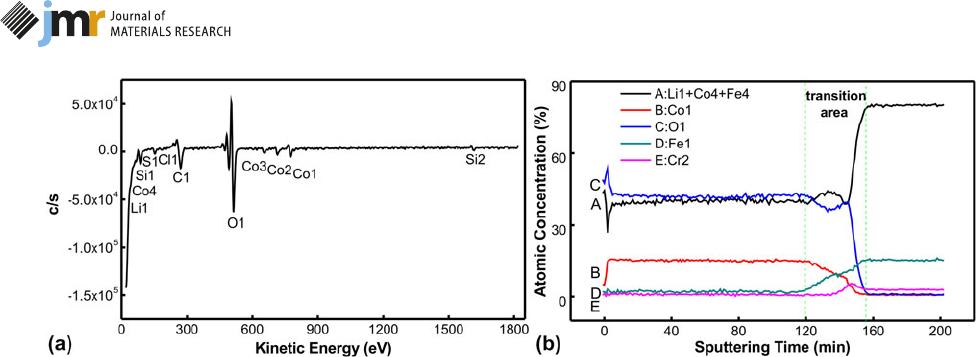

An AES spectrum and an auger depth pro file in Fig. 6 are

used to indicate the inter-diffusion between LiCoO

2

and SS

[42]. Using SS as substrates, elements from both LiCoO

2

and SS

can diffuse into each other. The LiCoO

2

films become semi-

conducting due to Fe, Cr doping [17, 18], while SS is lightly

oxidized by O atoms from LiCoO

2

. Figure 6(a) shows the AES

spectrum obtained from the LiCoO

2

film surface. It consists of

Li, Co, and O at the surface. The auger peak of Li1 (39 eV) is

particularly affected by Fe

4

(50 eV) and Co

4

(57 eV), and the Li

element signal cannot be deducted from Co and Fe during

post-data processing. An auger depth profile of the annealed

LiCoO

2

films is shown in Fig. 6(b); it clearly shows that the

stoichiometric ratio of Li:Co:O is stable at ;1:1:2 in the LiCoO

2

film zone. Fe, Cr elements also have a steady concentration in

the SS substrate zone. However, Li, Co, O, Fe, and Cr in the

transition zone between LiCoO

2

and SS vary with the

Figure 5: The (a)–(i) charge/discharge curves and corresponding (a‘)–(i‘) cycle performance of LiCoO

2

films annealed at different atmospheres, temperatures,

holding times, and heating rates, and these annealing parameters are marked at the lower left corner.

Article

ª Materials Research Society 2019 cambridge.org/JMR 6

j Journal of Materials Research j www.mrs.org/jmr

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. La Trobe University, on 27 Oct 2019 at 05:00:57, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1557/jmr.2019.299

sputtering depth. The content of Li

1

1 Co

4

1 Fe

4

has

a complex diversification; the decline curve in the initial stage

is mainly caused by Li, Co reduction; and the latter sharp

increment is caused by the Fe content from SS. The Co

1

atomic

content decreases linearly from 15 to 0% with the increased

sputtering depth. The O

1

signal decreases slowly from 41 to

37% at the initial 2/3 stage and then decays to nearly 0. Fe

1

and

Cr

2

increase linearly from 2% to 15% and 0% to 4% with

sputtering depth, respectively.

So the diffusion of impurity from the SS substrate into

LiCoO

2

is the main reason for the destruction of the compo-

sition of LiCoO

2

and it also reduces LiCoO

2

discharge capacity.

The films obtained at 500 °C in Fig. 5(d) express a short

discharge platform near the 3.8 V position, which may

correspond to an unexpected Li

x

Co

2

O

4

phase, whose structure

falls between the ideal layered structure and the ideal spinel

structure [13]. In addition, cycle stability of the sample at

500 °C only lasts 37 times because the large LiCoO

2

surface

roughness results in uneven current density distributions,

which may lead to lithium dendrite and short circuits. The

1st and 37th discharge capacities are 32.53 lA h/(cm

2

lm) and

13.37 lA h/(cm

2

lm), respectively. This short-circuit is figured

out according to its columbic efficiency in Fig. 5(d9). The half-

cell assembled by the sample A6 can only cycle 37 times

normally; it stays in a charge state but do not discharge when

reaching the cutoff voltage at the 38th cycle. In addition, the

columbic efficiency of this half-cell remains at 97% for 31

cycles and it decays to 24% from the 31st cycle to 38th cycle.

The formation of lithium dendrite may cause short-circuits

because the declination of columbic efficiency along with the

cycle numbers reflects the formation of lithium dendrite [5].

Furthermore, both the short discharge platform and limited

cycle life indicate that 500 °C cannot meet the perfect

crystallization of LiCoO

2

films. It is necessary to increase T

or extend the holding time further. As T increases to 550 or

600 °C, the initial discharge capacity is equal to 41.06, 32.05 lA

h/(cm

2

lm) separately, and the highest discharge capacity

retention ratio equals to 64.34%, 87.69% at the 50th cycle, as

shown in Figs. 5(a), 5(a9), 5(e), and 5(e9). Particularly, the

LiCoO

2

films annealed at T . 625 °C have the discharge

capacity of ;0; this may be a result of the LiCoO

2

component

destruction caused by inter-diffusion or severe side reactions.

Holding time and heating rate

The interface diffusion between LiCoO

2

and SS is inevitable

during the annealing process. This partially changes the LiCoO

2

composition and impairs the discharge capacity of the LiCoO

2

cathodes severely. However, the interface diffusion can be

controlled by tuning the holding time and heating rate. The

surface particles on the sample A11 without heat preservation (0

min) in Fig. 2(k) are in an irregular shape and are packed-up

together. While the sample A12 annealed at 550 °C, holding for

10min[asshowninFig.2(l)]formsaregulargranulargrain

shape, but the average grain size is smaller than 30 nm. Besides,

thegrainshapetransformsintoatriangleshapewhentheholding

time exceeds 30 min and the grain size becomes more uniform

with the extended holding time, as shown in Figs. 2(m) and 2(n).

ThesampleA15withthelongestholdingtimeof;120 min

[Fig. 2(o)] corresponds to an average grain size of 100 nm.

Especially, the selected heating rate range (2–13 °C/min) corre-

sponding to Figs. 2(p)–2(s) have no obvious effect on the LiCoO

2

surface morphologies, all of which are uniform and loosely

packed, and the average crack width is ;100 nm [30].

The lattice orientation of LiCoO

2

films annealed with

different holding times and heating rates is given in Figs. 4(c)

and 4(d) individually. Both holding time and heating rate

mostly affect the intensities of the (003) diffraction peak. For

example, the samples with no holding time (0 min) or with

higher heating rates (5 °C/min and 10 °C/min) express distinct

(003) grains, and the intensity of the (003) peak attenuates as

the holding time increases or the heating rate decreases.

In the case of the films grown at different holding times

and diverse heating rates, there exists a holding time or

Figure 6: (a) AES spectrum of LiCoO

2

films surface and (b) auger depth profile of the LiCoO

2

films grown on SS. Different element types are marked with letters A,

B, C, D, and E.

Article

ª Materials Research Society 2019 cambridge.org/JMR 7

j Journal of Materials Research j www.mrs.org/jmr

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. La Trobe University, on 27 Oct 2019 at 05:00:57, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1557/jmr.2019.299

a heating rate that corresponds to the best capacity. For the

sample annealed in 10 min in Figs. 5(f) and 5(f9), the discharge

capacity at 1st/50th is equal to 34.31/11.08 lA h/(cm

2

lm),

respectively. Once the holding time exceeds more than 30 min,

the discharge curves quickly reach 3.9 V with cycle numbers.

Battery internal resistance increases with holding time possibly;

the reason for the increased impedance is the loss of Co and the

dislodged structures of LiCoO

2

, and black traces of LiCoO

2

material on the separator in the literature support the claim

[32]. In Figs. 5(g) and 5(g9), the LiCoO

2

sample with a ramping

rate of 3 °C/min has the 1st discharge capacity of 37.56 lAh/

(cm

2

lm) and capacity retention of 83.81% at the 50th cycle,

and the sample annealed with 5 °C/min has the equivalent

values of 41.48 lA h/(cm

2

lm) and 70.07%, as shown in

Figs. 5(h) and 5(h9). The sample annealed with 13 °C/min in

Figs. 5(i) and 5(i9) has the 1st discharge capacity of 38.07 lAh/

(cm

2

lm) and capacity retention of 70.82% at the 50th cycle.

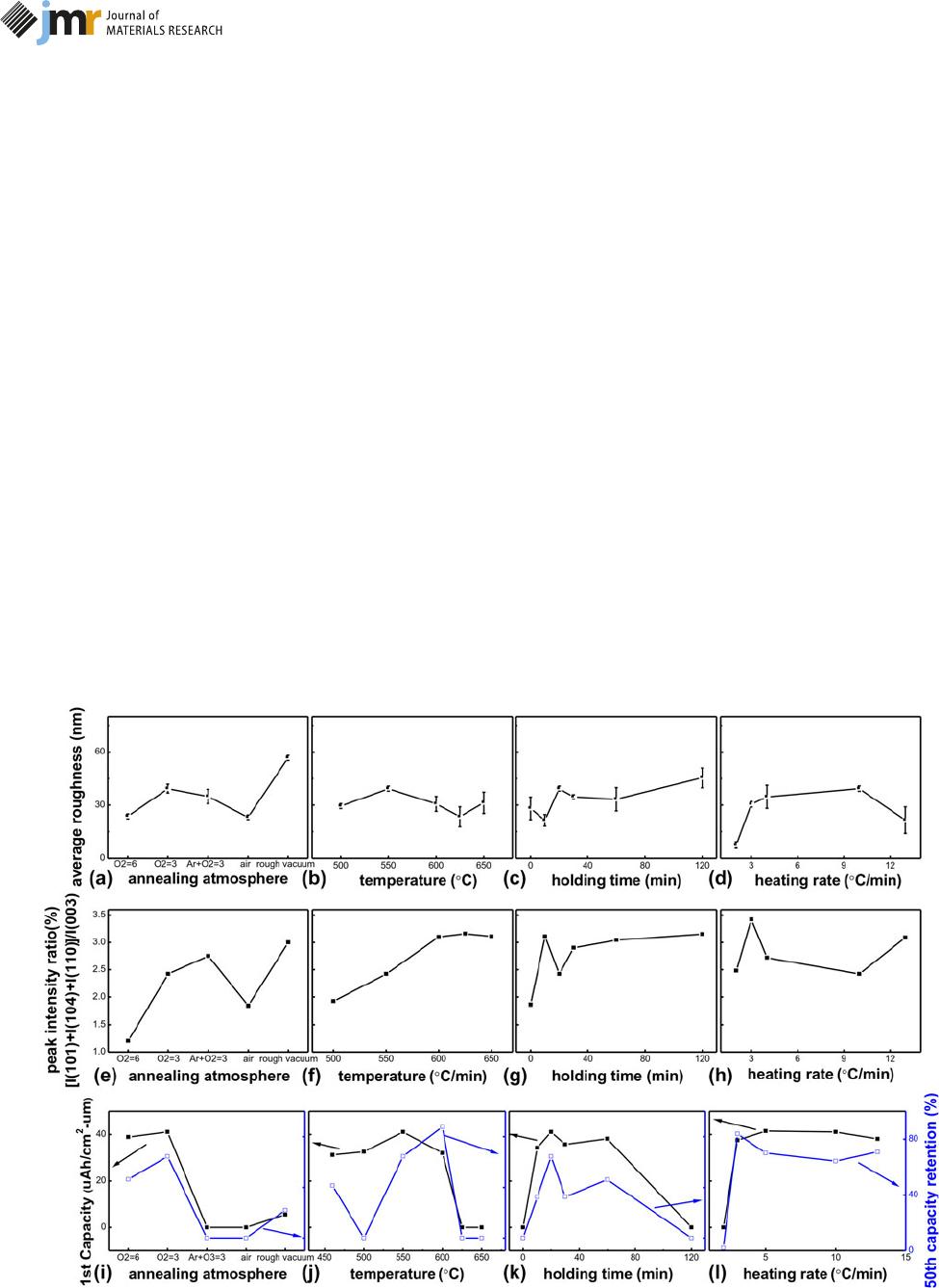

Comparison of the parameters

Since the properties of the LiCoO

2

films strongly correlate with

their compositions, morphologies, and structures, it is neces-

sary to take the synthetic effects into account. Figure 7

summarizes several important parameters: surface roughness,

peak intensity ratio [I

(101)

1 I

(104)

1 I

(110)

]/I

(003)

, the 1st

discharge capacity, and capacity retention rate at the 50th cycle

for selection of the optimum annealing process.

In Figs. 7(a)– 7( d), the average roughness of all the

annealed LiCoO

2

films lies between 10 and 60 nm; this

roughness can be acceptable because the separator thickne ss

(30 lm) is thicker than the roughness. Annealing atmosphere

has the most obvious impact on roughness. The sample

annealed under rough vacuum has the largest roughness of

56.68 6 12.69 nm; the high roughness corresponds to

a large activation area, but more likely leads to battery failure.

The other annealing conditions lead to an average roughness

of ;30 nm.

The value of c/a lies among 4.95–5.00 and reflects the layer

spacing for Li

1

transfer; however, the peak intensity ratio of

[I

(101)

1 I

(104)

1 I

(110)

]/I

(003)

lies between 1.20 and 3.42 with

varied annealing processes, as shown in Figs. 7(e) and 7(f).

Generally, the (101) and (104) planes facilitate de-intercalation

of Li

1

and correspond to a high initial discharge capacity; the

(003) plane can maintain structure stability during the Li

1

transfer process and a long cycle life can be achieved [43, 44,

45], so the ratio of [I

(101)

1 I

(104)

1 I

(110)

]/I

(003)

can reflect the

comprehensive electrochemical performance of LiCoO

2

cath-

odes directly. The maximum c/a value of 4.98 and maximum

Figure 7: Summary of the influences of annealing atmospheres, temperatures, holding times, and heating rates on (a)–(d) surface roughness, (e)–(h) peak

intensity ratio [I

(101)

1 I

(104)

1 I

(110)

]/I

(003)

, and (i)–(l) the 1st discharge capacity (solid point) and the 50th capacity retention ratio (hollow point).

Article

ª Materials Research Society 2019 cambridge.org/JMR 8

j Journal of Materials Research j www.mrs.org/jmr

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. La Trobe University, on 27 Oct 2019 at 05:00:57, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1557/jmr.2019.299

ratio [I

(101)

1 I

(104)

1 I

(110)

]/I

(003)

of 3.42 are preferred for the

LiCoO

2

crystal structure.

Electrochemical performance of the LiCoO

2

filmsisthe

combined effect of the film’s composition and structure. The 1st

discharge capacity and 50th capacity retention are two key

indicators for LiCoO

2

annealing works, and their change trends

arerelatedtothechangeruleoftheratioof[I

(101)

1 I

(104)

1

I

(110)

]/I

(003)

. In Figs. 7(i)–7(l), the normal value of the 1st

discharge capacity is at 32.05–41.48 lAh/(cm

2

lm), which is

lower than the theoretical value of 69 lAh/(cm

2

lm) [46]; this is

mainly caused by the diffusion and contamination from SS

substrates. The 50th capacity retention varies between 32.28 and

87.69%; some annealed samples can be confirmed to behave

a long cycle life according to the index of 80% capacity retention.

An optimum annealing process (pure O

2

, 550 °C, 20 min, and

3 °C/min) for large-scale LiCoO

2

filmsisproposedthrough

comparison with these characteristic values (as shown in Fig. 7),

corresponding to the initial discharge capacity of 37.56 lAh/(cm

2

lm) and capacity retention at the 50th cycle of 83.81%.

Conclusions

The crystal LiCoO

2

cathode on a flexible SS has been successfully

obtained by annealing with a traditional tube furnace. According

to the different annealing conditions, a pure oxygen annealing

atmosphere is confirmed first because the LiCoO

2

composition

ratio is the basis. T is the second important factor for an ideal

layered form of LiCoO

2

cathode because T can directly change the

crystal structures. After T ensures LiCoO

2

crystallization, the

holding time needs to be chosen to be as short as possible to limit

the SS oxidation and inter-diffusion, and it is equivalent to cutting

down the holding time or accelerating the heating rate to optimize

the LiCoO

2

annealing process.

In the end, LiCoO

2

films annealed at 550 °C for 20 min

under pure oxygen (O

2

5 3 sccm, 3.5 Pa) and with a heating rate

of 3 °C/min show the optimum electrochemical performance in

our system. The initial discharge capacity is 37.56 lAh/(cm

2

lm)

and the capacity retention at the 50th cycle is 83.81%.

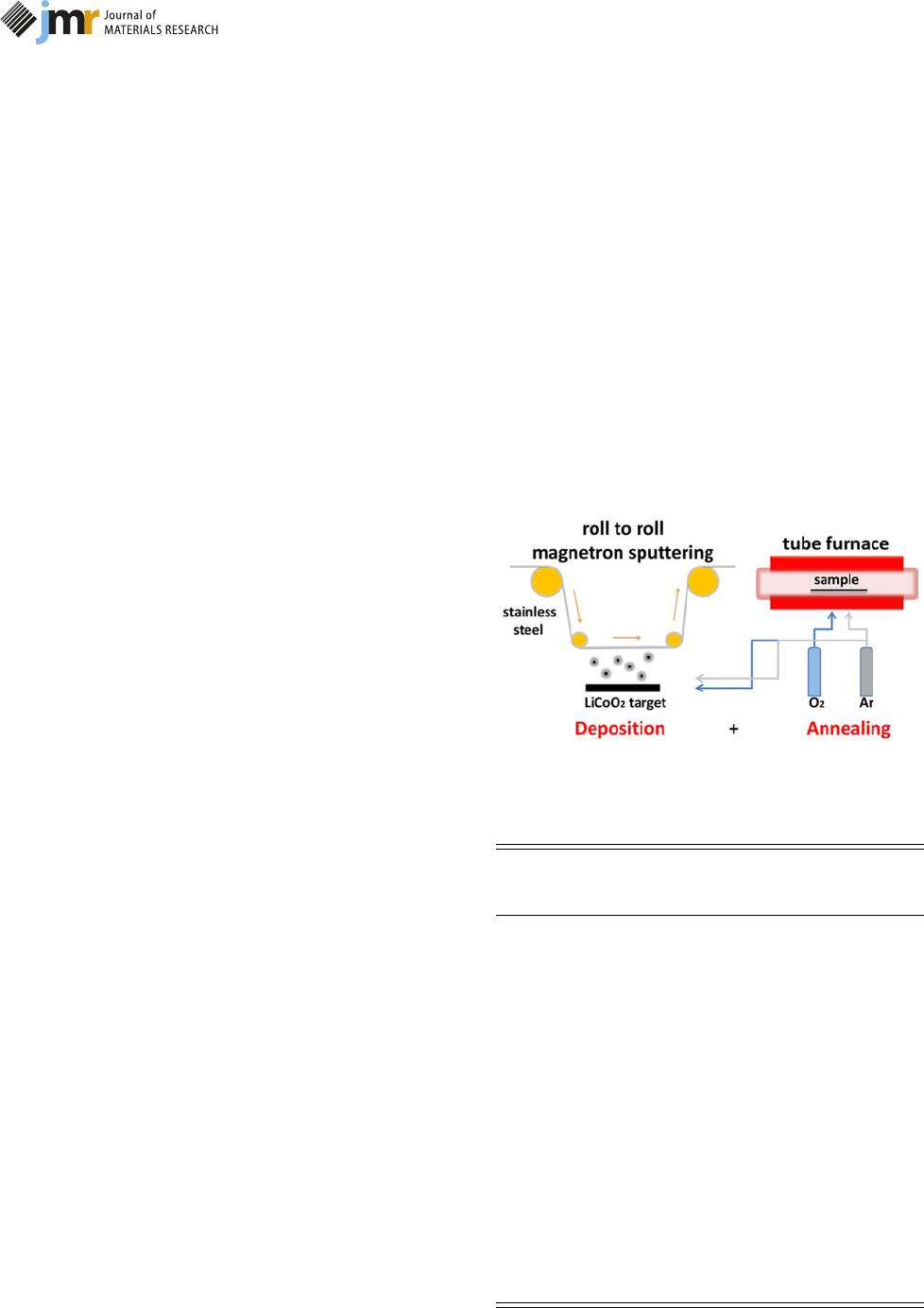

Experimental

LiCoO

2

film deposition and annealing

A roll of SS (SUS304) with dimension of 2.0 0.5 m was, first,

wiped with ethanol to remove surface contaminants and release

residual stress. The nominal thickness equaled to 0.03 mm and

the density was 7.93 g/cm

3

. The preparation and annealing

process are shown in Fig. 8; the LiCoO

2

films were fabricated

by MS with a power density of 4 W/cm

2

and the working

pressure during the whole deposition was 1.0 Pa. A uniform

film thickness of 1.1 lm was achieved by controlling the

dynamic deposition rate and deposition time. In fact, the film

thickness actually equals to 1.09 lm by calibration of the cross-

section image, and the deposited LiCoO

2

film had an areal

loading of 0.28 mg/cm

2

. The as-grown LiCoO

2

films were

annealed according to the annealing parameters shown in

Table II. Among them, the annealing experiment marked with

A1 acted as reference and the other experiments changed only

one parameter once based on A1.

Half-cell assembly and electrochemical

performance test

The half-cells were assembled with an Li foil as a counter-

electrode and 0.5 M LiPF

6

in an EC and DMC mixture solvent

(volume ratio is 1:1). The used polyethylene (PE) separator was

purchased from Linyi Gelon New Battery Material Co., Ltd.,

Shandong, China. This separator was prepared by a dry stretching

method, the holes on its surface were elliptical shapes with the long

Figure 8: Schematic diagram of LiCoO

2

film deposition and annealing.

TABLE II: LiCoO

2

film thermal treatment parameters.

Category

Batch

number

Annealing

atmosphere

(sccm)

Annealing

temperature

(°C)

Holding

time

(min)

Heating

rate (°C/

min)

Reference A1 O

2

=3 550 20 10

Annealing

atmosphere

A2 Ar:O

2

=

1.5:1.5

550 20 10

A3 Air 550 20 10

A4 Rough

vacuum

550 20 10

A5 O

2

=6 550 20 10

Annealing

temperature

A6 O

2

5 3 500 20 10

A7 O

2

5 3 550 20 10

A8 O

2

5 3 600 20 10

A9 O

2

5 3 625 20 10

A10 O

2

5 3 650 20 10

Holding

time

A11 O

2

5 3 550 0 10

A12 O

2

5 3 550 10 10

A13 O

2

5 3 550 30 10

A14 O

2

5 3 550 60 10

A15 O

2

5 3 550 120 10

Heating rate

A16 O

2

5 3 550 20 2

A17 O

2

5 3 550 20 3

A18 O

2

5 3 550 20 5

A19 O

2

5 3 550 20 13

Article

ª Materials Research Society 2019 cambridge.org/JMR 9

j Journal of Materials Research j www.mrs.org/jmr

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. La Trobe University, on 27 Oct 2019 at 05:00:57, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1557/jmr.2019.299

side of ;80 nm and width of ;30 nm, and its average thickness

was confir med to be 30 6 2 lm. Additionally, the electrolyte

amount was strictly controlled by a pipettor (MicroPette, 100–500

lL, Dragon Laboratory InstrumentsLtd.,Beijing,China),and

a total of 200 lL electrolyte were controlled for each half-cell. The

charge/discharge test was preceded on a LAND machine

(CT2001A, Wuhan LANDHE Electronic Co., Ltd., Wuhan, China)

using a constant current density of 16 lA/cm

2

between 3.0 and

4.2 V in a glove box. Especially, the initial discharge capacity and

the capacity retention rate at the 50th cycle were chosen as

selection standards for the charge/discharge performance.

Film characterization

Film crystal structure was investigated using a grazing incidence

X-ray mode diffractometer (XRD-SmartLab, Rigaku Co., Tokyo,

Japan; Cu K

a1

radiation, k 5 0.15405 nm, an X-ray tube voltage

of 40 kV, a tube current of 15 mA) in order to minimize

interference from substrates. The measurement procedure fixed

the incident angle at 5° with respect to substrate surface and

restricted scanning interval of 10° # 2h # 80°. And then, the

original XRD data were made by background correction and K

b

stripping. The surface morphology of each annealed LiCoO

2

film

was probed by using a field emission scanning electron micro-

scope (FESEM; SU 8010, Hitachi, Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), and the

surface roughness was detected by using an atomic force

microscope (AFM-Dimension Edge, Bruker Co., Karlsruhe,

Germany); a tapping mode and five measurement positions were

selected to calculate average roughnessanditsstandarddeviation.

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS; SXM PHI Quantera SXM,

ULVAC PHI, Inc., Kanagawa, Japan) was adopted to analyze

surface element types and valence states. Testing conditions were

as follows: a hemispherical energy analyzer and monochromatic

Al target were chosen to detect C, Li, Co, O element signals; the

X-ray beam had a spot size of 200 lmandwasfixed with an

incident angle of 45°. The binding energy positions of different

elements were calibrated by the contaminated carbon position

(C 1s,284.8eV),andthepeakfitting procedure was performed

by a nonlinear fitting method. At the same time, the AES

measurements were performed on the annealed LiCoO

2

films by

using the scanning auger microscope (Phi-700, ULVAC-PHI, Inc.,

Kanagawa, Japan). The electron gun sets a high voltage of 5 kV

and an incident angle of 30°. The analytical chamber vacuum is

lowerthan5.2 10

7

Pa, the sputtering gun uses Ar

1

,andthe

sputtering rate is 14 nm/min for SiO

2

.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support of

the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos.

21603204 and 51702305).

References

1. Y.S. Yoon, C.H. Park, and J.H. Kim: Lattice orientation control of

lithium cobalt oxide cathode film for all-solid-state thin film

batteries. J. Power Sources 226, 186 (2013).

2. H. Castaneda: The impedance response of different mechanisms

for LiCoO

2

/acetylene carbon electrodes in alkaline solutions under

polarization conditions. Electrochim. Acta 112, 562 (2013).

3. J.F. Ribeiro, R. Sousa, J.A. Sousa, L.M. Goncalves, M.M. Silva,

L. Dupont, and J.H. Correia:Flexiblethin-film rechargeab le lithium

battery. In Transducers (IEEE, Barcelona, Spain, 2013); p. 2233.

4. ID TechEx Ltd.: Flexible, printed and thin film batteries 2019–2029

(2018). Available at: https://www.giiresearch.com/report/ix314818-

flexible-printed-thin-film-batteries.html (accessed September 03, 2019).

5. H.S. Lee, S. Kim, K-B. Kim, and J-W. Choi: Scalable fabrication

of flexible thin-film batteries for smart lens applications. Nano

Energy 53, 225 (2018).

6. Z.M. Yang, G.J. Xing, J. Yang, C.H. Mao, and J. Du: Effects of

annealing temperature on structure and electrochemical properties

of LiCoO

2

cathode thin films. Rare Met. 25, 189 (2006).

7. Y.S. Yoon, S.H. Lee, S.B. Cho, and S.C. Nam:Influence of two-

step heat treatment on sputtered lithium cobalt oxide thin films. J.

Electrochem. Soc. 158, A1313 (2011).

8. H.K. Kim and Y.S. Yoon: Characteristics of rapid-thermal-

annealed LiCoO

2

cathode film for an all-solid-state thin film

microbattery. J. Vac. Sci. Technol., A 22, 1182 (2004).

9. H.Y. Park, S.C. Nam, Y.C. Lim, K.G. Choi, K.C. Lee, G.B. Park,

J.B. Kim, H.P. Kim, and S.B. Chao: LiCoO

2

thin film cathode

fabrication by rapid thermal annealing for micro power sources.

Electrochim. Acta 52, 2062 (2007).

10. K.F. Chiu, H.H. Hsiao, G.S. Chen, and H.L. Liu: Structural

evolution and stability of RF sputter deposited Li

x

Mn

2y

O

4

thin

film cathodes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 151, A452 (2004).

11. W.S. Kim: Characteristics of LiCoO

2

thin film cathodes according

to the annealing ambient for the post-annealing process. J. Power

Sources 134, 103 (2004).

12. S.W. Jeon, J.K. Lim, S.M. Lim, and S.M. Lee: As-deposited

LiCoO

2

thin film cathodes prepared by rf magnetron sputtering.

Electrochim. Acta 51, 268 (2005).

13. P.Fragnaud,R.Nagarahan,D.M.Schleich,andD.Vujic:Thin-film

cathodes for secondary lit hium batteries. J. Power Sources 54, 362 (1995).

14. Y.S. Kang, H. Lee, Y.M. Kang, P.S. Lee, and J.Y. Lee:

Crystallization of lithium cobalt oxide thin films by radio-

frequency plasma irradiation. J. Appl. Phys. 90, 5940 (2001).

15. Y.S. Kang, H. Lee, S.C. Park, P.S. Lee, and J.Y. Lee: Plasma

treatments for the low temperature crystallization of LiCoO

2

thin

films. J. Electrochem. Soc. 148, A1254 (2001).

16. British Stainless Steel Association: Heat tint (temper) colors on

stainless steel surfaces heated in air (2016). Available at: https://

www.bssa.org.uk/topics.php?article5140 (accessed September 03,

2019).

Article

ª Materials Research Society 2019 cambridge.org/JMR 10

j Journal of Materials Research j www.mrs.org/jmr

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. La Trobe University, on 27 Oct 2019 at 05:00:57, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1557/jmr.2019.299