New Techniques for Damage Assessment

of Diesel Particulate Filters

Tim Hands and Qiang Li

Abstract The maximum soot load capacity for ceramic Diesel Particulate Filters

(DPFs) is sometimes limited by a thermal crack failure mechanism associated with

high temperature gradients which can occur during regeneration of highly loaded

parts—particularly at low exhaust flow rates. The filter material and construction

can be optimised for resistance to thermal cracking, however, the precise condi-

tions which give rise to thermal failure of DPFs can be difficult to establish

accurately and repeatably. For instance, thermal failure of DPFs may occur at the

onset of the heating due to the exotherm of trapped soot, or during cooling (for

instance at the fuel cut during deceleration or start of idle). The time of occurrence

of thermal failure can help to establish the worst conditions for filters. Sectioning

parts post-test is often conducted to establish the nature and location of any

damage. However non-destructive testing allows for the possibility of progressive

testing of single parts—allowing determination of the ‘Soot Mass Limit’. Post-test

scanning techniques have been demonstrated (e.g. X-Ray/CT scanning). These

allow non-destructive testing, but are generally expensive, and require the DPF to

be removed from the can. This paper describes important considerations for

application of two existing post-test evaluations as follows. (1) Radial and axial

ultrasound ‘Time-of-flight’ measurement. (2) Internal imaging of the DPF with a

small borescope. Also presented are two novel non-destructive techniques for

assessing damage to DPFs as follows. (1) An in situ technique capable of mea-

suring filter vibration events during DPF operation which may be associated with

F2012-A04-006

T. Hands

Cambustion Ltd, Cambridge, UK

e-mail: [email protected]

Q. Li (&)

Cambustion China Office, Shanghai, China

SAE-China and FISITA (eds.), Proceedings of the FISITA 2012 World

Automotive Congress, Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering 189,

DOI: 10.1007/978-3-642-33841-0_47, Ó Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013

609

thermal crack damage. A surface microphone coupled directly to the filter sub-

strate through a hole in the can and intumescent matting measures brick vibration,

while a background detector measures exhaust pipe and canning vibration events

in order to discriminate metallic thermal expansion. Vibration and internal ther-

mocouple data is presented from exothermic regenerations for several different

filters loaded with soot on a commercial Diesel Particulate Generator with standard

Diesel fuel and fuel treated with a catalytic additive. The extension of the tech-

nique to testing on a vehicle is demonstrated. (2) A relatively simple, post-test

evaluation which involves reverse aspiration of DPF test parts with a cold Diesel

soot aerosol generated with compressed air. The technique can locate DPF cells

where the soot aerosol is not filtered though the substrate between the inlet and

outlet channels. The deposition of soot on the substrate is shown to be an indicator

of internal damage and, together with simple optical microscopy, can help to

identify failure mechanisms. The paper presents examples of the above techniques

to examine thermal damage to Silicon Carbide and Aluminium Titanate DPFs

which have been subject to ‘worst case’ regenerations.

Keywords DPF

Crack

SML

DPG

Diesel

1 Introduction

The regeneration of heavily loaded Diesel Particulate Filters (DPF) parts can cause

thermal damage to DPF substrates due to the high thermal gradients associated

with the exothermic oxidation of the deposited soot.

The threshold of thermal damage depends on the physical properties of the DPF

material used—including: thermal conductivity, heat capacity, material strength

(fracture toughness K

Ic

), Coefficient of Thermal Expansion (CTE), Young’s

modulus (E), melting point/maximum application temperature. Further, the

application of a catalytic coating to the DPF or addition of a fuel borne catalyst can

significantly affect the threshold of exothermic reaction.

Most wall flow DPFs fall into two categories as follows:

Monolith These have a single brick construction and are usually made from

Cordierite.

Segmented For vehicle applications, these are typically made from individual

segments which are cemented together. They are usually made from

Silicon Carbide.

The differences in the physical and thermal properties of these filter types leads

to significant differences in thermal damage resistance (usually associated with

loaded regeneration).

610 T. Hands and Q. Li

1.1 Damage Assessment

An important part of Soot Mass Limit Testing is the method by which a part is

determined to be damaged.

1.1.1 Filtration Performance

Concerning the degradation in the filtration performance of a part, the assessment

of filtration should be made on a DPF part which is loaded from clean, since the

filtration performance is a strong function of the soot loaded onto the part at small

soot loads. Further, for small cracks, the accumulation of soot on the part can

‘bridge’ or plug the cracks and restore filtration performance. This behaviour of

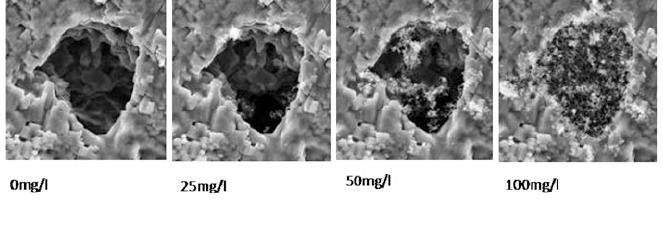

soot can be observed in Figs. 1 and 2.

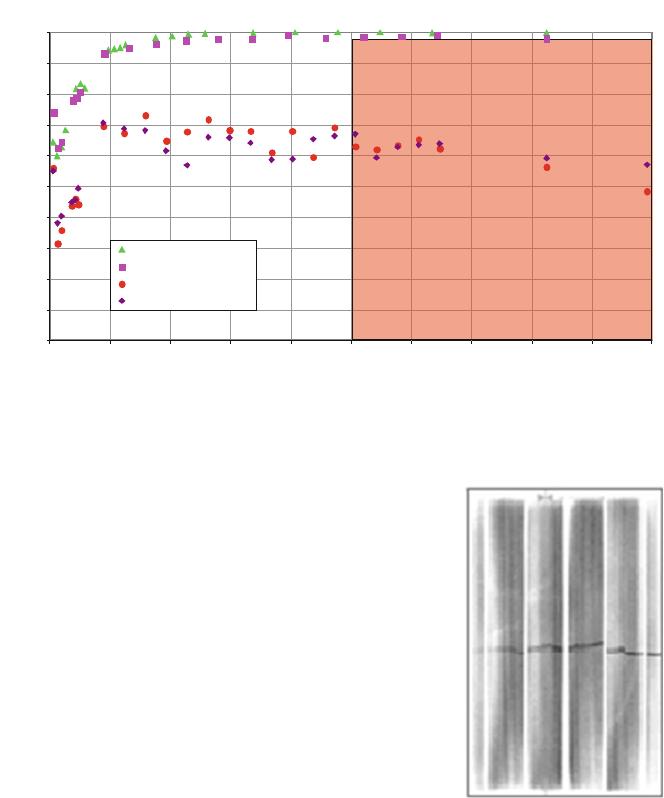

Figure 2 shows the change in soot mass filtration efficiency following Soot

Mass Limit tests of increasing severity with soot load measured with an AVL415S

smoke meter.

Some workers have adopted the criterion for damage to a part to be a reduction

in filtration efficiency of more than one percent at a total accumulated soot load of

0.5 g. By this criterion, the data in Fig. 2 indicates that the Soot Mass Limit for

this part is between base load (6 g soot/l) and base load +15 % (6.9 g soot/l).

1.1.2 Mechanical Integrity

Although DPFs may leak due to missing end plugs or manufacturing faults, the

cause of the degradation in filtration performance is generally due to internal

cracks. Computerised Tomography using X rays can produce images of internal

cracks (see Fig. 3).

However, this technique is relatively expensive and requires the DPF to be

removed from its can. This paper describes alternative techniques to identify

damaged parts.

Fig. 1 TEM pictures of soot loading onto a DPF from clean (from [9])

New Techniques for Damage Assessment of Diesel Particulate Filters 611

2 Instrumentation

2.1 Existing Post-Test Evaluation Techniques

This section discusses two techniques which can only be conducted post-test, when

the sample is cooled and with reasonable access to the rear face of the DPF.

DPF Filtration Efficiency

50

55

60

65

70

75

80

85

90

95

100

0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6

0.7

0.8 0.9 1

Soot Load (g)

Filtration Efficiency %

De-greened part

Base load

Base + 15%

Base + 30%

Fail

Fig. 2 Mass-based filtration efficiency of a DPF as a function of total soot load

Fig. 3 CT image of radial

crack in SiC DPF from [1]

612 T. Hands and Q. Li

2.1.1 Ultrasound Time of Flight Measurement

The technique of non-destructive inspection of rigid materials via Acoustic

Emission (AE) is well established [2]. Recently, it has been applied to alternative

materials including asphalt [3] and ceramic monoliths [4, 5].

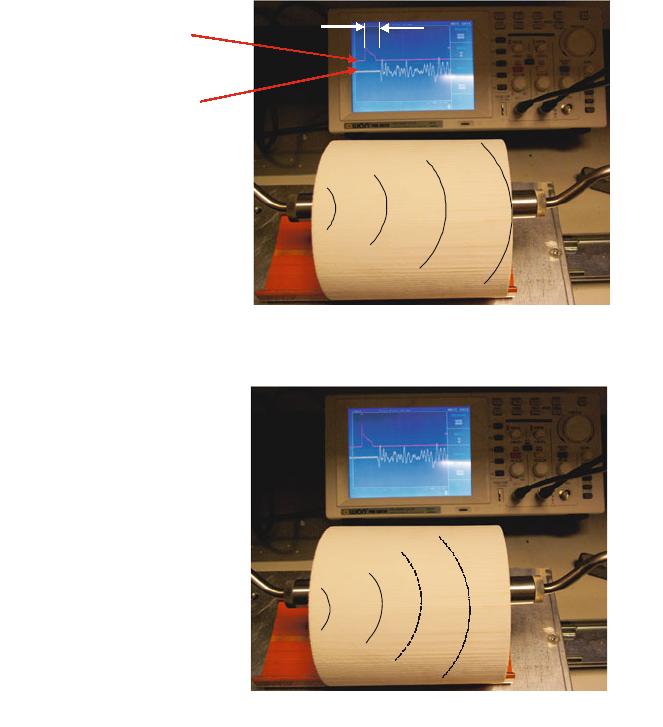

‘Time of flight’ measurements were made using a Pundit plus Model PC1006.

The system uses a separate ultrasound emitter and detector and measures the

transit time through the substrate. The experimental arrangement is shown in

Figs. 4 and 5 for an ‘intact’ and damaged DPF respectively.

The figures above illustrate how a radial crack significantly attenuates and

delays the detected signal. If the part is not canned (as shown in the figures), it is

also possible to make radial measurements (across diameters of the DPF).

Emitter

signal

Detector

signal

‘Time of flight’ ~ 40us

For ‘Intact’ DPF

Fig. 4 Axial ultrasound measurement ‘intact’ DPF

‘Time of flight’ ~ ?

For cracked DPF

(Detector signal very

attentuated)

Fig. 5 Axial ultrasound measurement damaged DPF

New Techniques for Damage Assessment of Diesel Particulate Filters 613

When making these measurements, the following considerations are important:

1. The coupling of the emitter and detector to the surface of the DPF has a strong

effect on the detected signal. We have found that Blu-tack [6] with a thickness

of *2 mm gives good and repeatable acoustic coupling for the detector and

emitter.

2. The compressive force by which the emitter and detector are coupled to the

DPF also has a strong effect on the detected signal (a high compressive force

can tend to close cracks which tends to reduce transit times and generally

increase the energy in the transmitted signal). In order to obtain repeatable

results, a mechanical arrangement which keeps this force constant is required.

2.1.2 Internal Borescope Inspection

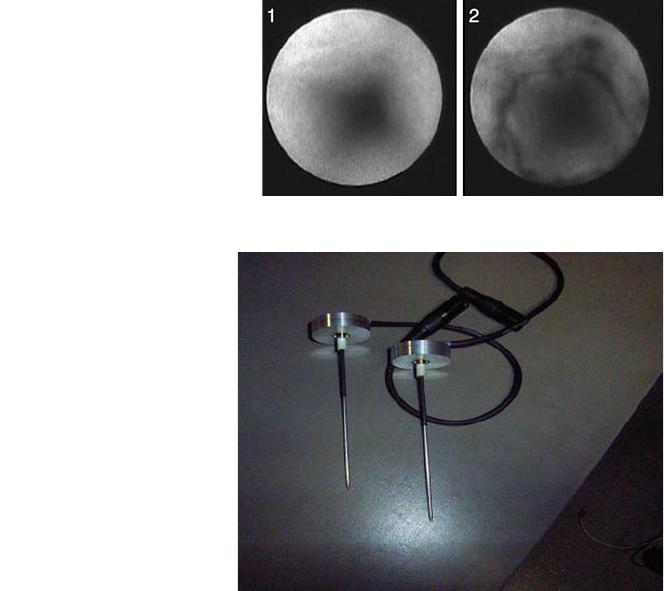

Some workers have used a small diameter borescope (e.g. [7]) to inspect individual

cells of a DPF. In order for the technique to work well, the part should be loaded

with a small amount of soot. The optical fibre bundle (*0.5 mm diameter) is

inserted down the exit cell of a DPF with suspected crack as shown in Fig. 6.

As the fibre is traversed along the length of the cell, where the cell walls are

intact, there is no evidence of soot (see image 1 in Fig. 7). However, a cracked cell

allows soot through from the inlet side of the DPF and a black line is observed (see

image 2 in Fig. 7).

Note that this technique is most sensitive where there is good contrast between

the DPF substrate and the soot (it is more difficult to locate cracks in SiC parts—

which are generally dark grey).

Fig. 6 Borescope inserted

into exit cells of DPF

614 T. Hands and Q. Li

2.2 Novel evaluation techniques

2.2.1 In-situ: Custom Vibration Detectors

During ‘worst case’ regenerations of loaded DPFs on a burner-based DPF testing

system (Cambustion DPG [8]) it was noted that damage to DPFs was associated

with audible cracks. These were distinct from the metallic creaks associated with

the rapid heating of the exhaust pipe and DPF can.

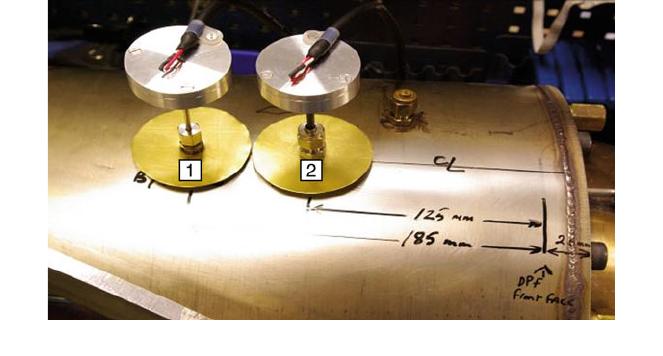

Custom surface microphones were developed where the microphone diaphragm

is remote from the DPF substrate, but coupled to it via a rigid rod. These are shown

in Fig. 8 and installed on a DPF test housing in Fig. 9.

The background sensor rod is coupled directly to the DPF can and responds

primarily to vibration ‘events’ associated with the exhaust pipe and DPF can. The

DPF crack sensor (2) in Fig. 9 is located in a stainless steel guide tube and the tip

is resting directly onto the surface of the DPF (a small hole is cut in the intu-

mescent matting to allow this). It responds primarily to vibration ‘events’ from the

DPF itself.

Fig. 7 Images of intact

channel (1) and damaged

channel (2)

Fig. 8 Custom surface

microphones with coupling

rods

New Techniques for Damage Assessment of Diesel Particulate Filters 615

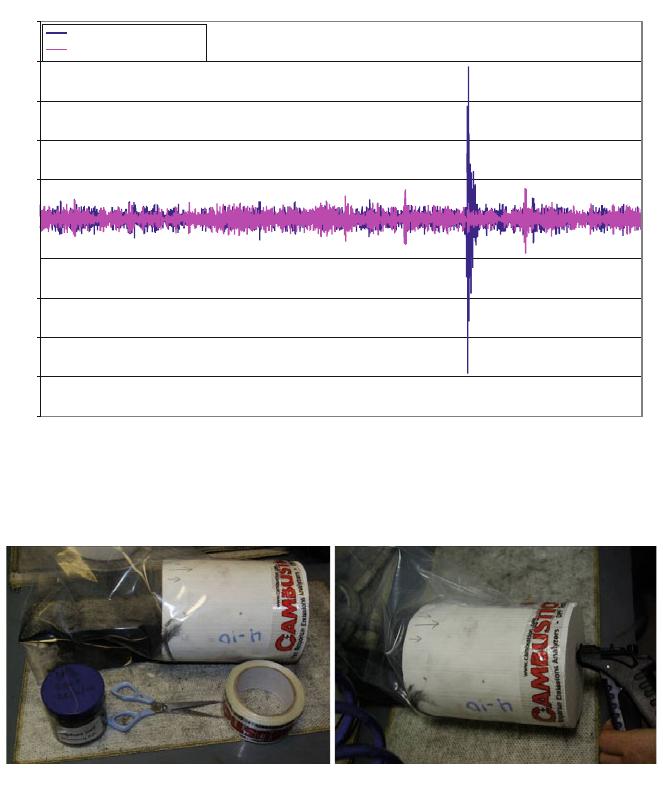

The raw vibration signals from these microphones are high-pass filtered in order

to accentuate the events associated with cracks. The high-pass filtered signals are

then monitored to produce a second by second output of DPF and background

crack activity.

2.2.2 Post Test: Reverse Soot Aspiration

A damaged DPF part can provide a transit path for soot through a crack rather than

through the wall of the filter. If a highly concentrated soot aerosol is blown through

a DPF (from entry to exit), the portion of aerosol travelling through the walls of the

DPF will be filtered and therefore no soot will arrive at the exit face. For a

damaged part however, soot can travel from the entry face to the exit face without

being filtered.

Some workers use a smoke aerosol and laser sheet on the entry face to observe

this ‘leakage’. An alternative novel technique conducted on a clean, cold DPF is

illustrated below.

1. A sample of Diesel soot (typically several grams) is placed into a polythene bag

which is sealed around the entry face of the DPF (upper picture).

2. Clean compressed air is blown backwards through the DPF (from exit to entry)

creating a jet of air at the entry. This jet stirs the Diesel soot and creates a

highly concentrated aerosol which then travels through the DPF (from entry to

exit)—with a total flow rate similar to the compressed air jet.

3. As the air jet is moved over the surface of the suspect DPF, all cells of the DPF

are exposed to highly concentrated Diesel aerosol (lower picture) (Figs 10, 11).

Where a part is damaged, the soot exiting the front face of the DPF via cracks

leaves a black deposit. Figure 12 shows a part after reverse aspiration. Missing/

Fig. 9 Background (1) and DPF (2) crack sensors installed on DPF can

616 T. Hands and Q. Li

damaged plugs are evident at the bottom and top left of the image and a crack

across the part is also evident.

Note that this technique is also most sensitive where there is good contrast

between the DPF substrate and the soot (it is more difficult to locate cracks in SiC

parts—which are generally dark grey).

Filtered vibration sensor

-0.05

-0.04

-0.03

-0.02

-0.01

0

0.01

0.02

0.03

0.04

0.05

350.95 350.97 350.99 351.01 351.03 351.05

Time (s)

Crack sensor filtered

Can sensor filtered

Fig. 10 DPF crack (blue) and can (pink) sensors filtered response to single brick crack

Fig. 11 Reverse aspiration of DPFs with soot aerosol

New Techniques for Damage Assessment of Diesel Particulate Filters 617

3 Test Program

Two Passenger car DPFs were tested as follows:

1. SiC uncoated 5.66

00

9 10

00

.

2. Aluminium Titanate uncoated 5.66

00

9 8

00

.

These parts were successively loaded to higher and higher soot loads and

regenerated with a ‘worst case’ regeneration (heated to *700C inlet at 63 kg/hr,

overall lean) whilst being continually monitored for cracks. The tests are sum-

marised in Table 1.

The parts were instrumented with internal 0.5 mm thermocouples inserted from

the rear face in order to resolve the temperature field during the regeneration

(Table 3).

4 Results

4.1 SiC In Situ Crack Data

See Figs. 13–15.

Fig. 12 Crack and missing/

damaged cell plugs

Table 1 DPF test program

Soot load (g/l) SiC 5.66 9 10

00

AT 5.66 9 8

00

8 4 (with Eolys fbc) 4

12 4 (with Eolys fbc) 4 (with and without Eolys fbc)

15 4

618 T. Hands and Q. Li