REVIEW ARTICLE

Telehealth in the rehabilitation of female pelvic floor dysfunction:

a systematic literature review

Kyannie Risame Ueda da Mata

1

& Rafaela Cristina Monica Costa

1

& Ébe dos Santos Monteiro Carbone

1,2

&

Márcia Maria Gimenez

1,2

& Maria Augusta Tezelli Bortolini

2

& Rodrigo Aquino Castro

2

& Fátima Faní Fitz

1,2

Received: 31 July 2020 /Accepted: 23 October 2020

#

The International Urogynecological Association 2020

Abstract

Introduction and hypothesis The pandemic caused by coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) increased the awareness and

efforts to provide care from distance using information technologies. We reviewed the literature about the practice and effec-

tiveness of the rehabilitation of the female pelvic floor dysfunction via telehealth regarding symptomatology and quality of life

and function of pelvic floor muscles (PFM).

Methods A bibliographic review was carried out in May 2020 in the databases: Embase, Medline/PubMed, LILACS and PEDro.

A total of 705 articles were reviewed after the removal of duplicates. The methodological quality of the articles was evaluated by

the PEDro scale. Two authors performed data extraction into a standardized spreadsheet.

Results Four studies were included, two being randomized controlled trials. Among the RCTs, only one compared telehealth

with face-to-face treatment; the second one compared telehealth with postal treatment. The other two studies are follow-up and

cost analysis reports on telehealth versus postal evaluation. Data showed that women who received the intervention remotely

presented significant improvement in their symptoms, such as reducing the number of incontinence episodes and voiding

frequency, improving PFM strength and improving quality of life compared to women who had the face-to-face treatment.

Conclusions Telehealth promoted a significant improvement in urinary symptoms, PFM function and quality of life. Telehealth is

still emerging, and more studies are needed to draw more conclusions. The recommendations of the governmental authorities,

physical therapy councils and corresponding associations of each country also need to be considered.

Keywords Telemedicine

.

Telemotoring

.

Pelvic floor

.

Urinary incontinence

.

Women’shealth

Introduction

Telehealth involves health care services, support and informa-

tion provided remotely via digital communication and de-

vices. It intends to facilitate effective delivery of health ser-

vices such as physical therapy by improving access to care and

information and managing health care resources [1]. Other

terms such as telemedic ine, telemonitoring, tele-education

and tele-assistance describe digital practice [2]. Due to the

pandemic caused by coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19),

health associations worldwide have released recommenda-

tions about care from distance using tools of communication

and information technologies [3–5].

In clinical practice, however, it is still unclear how the

professionals can perform rehabilitation of female pelvic floor

dysfunction via telehealth.

Before starting a pelvic floor muscle (PFM) training pro-

gram, one must ensu re that the patients are able to perform a

correct PFM contraction [6]. More than 30% of women are not

able to voluntarily contract the PFM at their first consultation

even with individual instruction verbally and by using digital

manual therapy [7, 8]. The success rate varies from 60% to 75%

when the PFM exercises are performed in the outpatient setting

[9, 10]. The literature has shown that home PFM training

(PFMT) provides equal benefit to outpatient PFMT in reducing

Supplementary Information The online version contains

supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-020-

04588-8.

* Fátima Faní Fitz

fanifitz@yahoo.com.br

1

Centro Universitário São Camilo, São Paulo, SP, Brazil

2

Department of Gynecology, Universidade Federal de São Paulo, Rua

Napoleão de Barros, 608 - Vila Clementino, São Paulo, SP CED

04024-002, Brazil

International Urogynecology Journal

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-020-04588-8

urinary symptoms when the patients attend some outpatient

sessions to monitor their exercises during their treatment [11,

12]. So, the question in telehealth is: How can we perform

rehabilitation of the pelvic floor in women in order to overcome

the issues of not using manual therapy in the process of pelvic

floor evaluation and teaching of PFM contraction?

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, adequate patient care is

urgently needed. So, alternatives in this dynamic clinical sit-

uation include systematic review as a way to connect evidence

and practice and to guide clinical care [13]. Therefore, the

purpose of the present study was to review telehealth in female

pelvic floor dysfunction rehabilitation. The outcome of inter-

est was the methodology by which the digital practice can be

performed. Secondarily, pelvic floor symptoms, quality of life

and function of the PFM were assessed.

Methods

Protocol and registration

This systematic review was developed following the PRISMA

guidelines. The systematic review protocol was registered in

the PROSPERO database under number CRD42020200457.

Eligibility criteria and study selection

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they were randomized

controlled trials and clinical trials that used telehealth in reha-

bilitation of female pelvic floor dysfunction. For this review,

digital practice was regarded as health care services, support

and information provided remotely via digital communication

as a form of intervention. We excluded studies that aimed only

to investigate new technologies such as mobile applications

and digital devices for home treatment with no comparator.

Information sources and search

The literature search was performed on May 2020 and includ-

ed studies from inception with no language restriction. The

consulted datab ases were: Embase, Medline/PubMed,

LILACS and PEDro (Physiotherapy Evidence Database).

The keywords u sed were: Telerehabi litation; Internet;

Videoconferencing; Tele; Continence; Women’sHealth;

Pelvic Floor; Telehealth; Urinary Incontinence ; Muscle

Dysfunction; Sexual Dysfunction; Pelvic Pain; Fecal

Incontinence; Pelvic Organ Prolapse. The search strategies

are described in the supplemental material (Supplement 1).

Screening and data extraction

A data search was performed by the authors (K.R.U.M. and

R.C.M.C.). A third author (F.F.F.) was consulted for a consensus

if discrepancies occurred. A standardized data extraction form

was used to collect the following data: authors, year of public a-

tion, journal, country of o rigin, sample, age (years), obje ctives,

outcome measure and results/conclusio ns. Data extraction was

performed by two independent raters (E.S.M.C. and M.M.G.).

Outcomes

The primary outcome was to investigate the telehealth meth-

odologies used by health professionals for PFM rehabilitation.

Secondarily, we investigated the effectiveness of telehealth in

PFM rehabilitation considering pelvic floor symptoms and

quality of life as well as PFM function in women with pelvic

floor dysfunctions.

Risk of bias assessment and analysis

The methodological q uality of the trials was assessed using the

PEDro scale (values of 0–10), with scores extracted from the

PEDro database [14]. The assessment of the quality of trials

was performed by two independent raters (M.A.T.B. and

R.A.C.), and disagreements were resolved by a third rater

(F.F.F.). Methodological quality was not an in clusion criterion.

As data were extracted and described, heterogeneity between

the outcomes did not allow poolin g data and performing sub-

group analysis or metanalysis. Results were displayed in tables in

a synthesized format. The description followed a narrative review

format.

Results

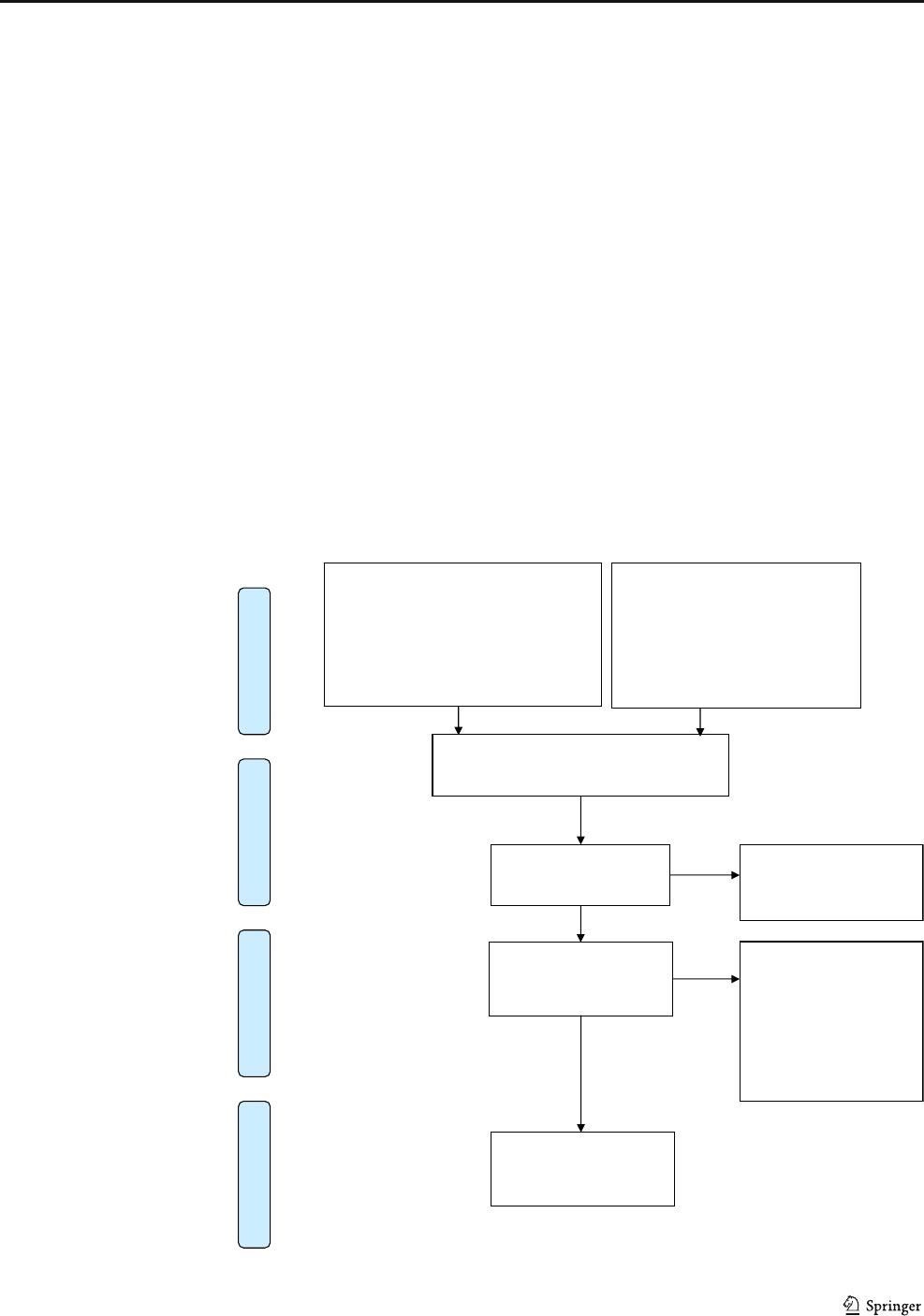

The first electronic database search resulted in a total of 705

articles after the removal of duplicates. As shown in Fig. 1,

eight articles were selected as potentially eligible on the basis

of their title and abstract, and four were excluded from analy-

sis after reading in full [15–18]. A total of four articles were

included in this review [19–21].

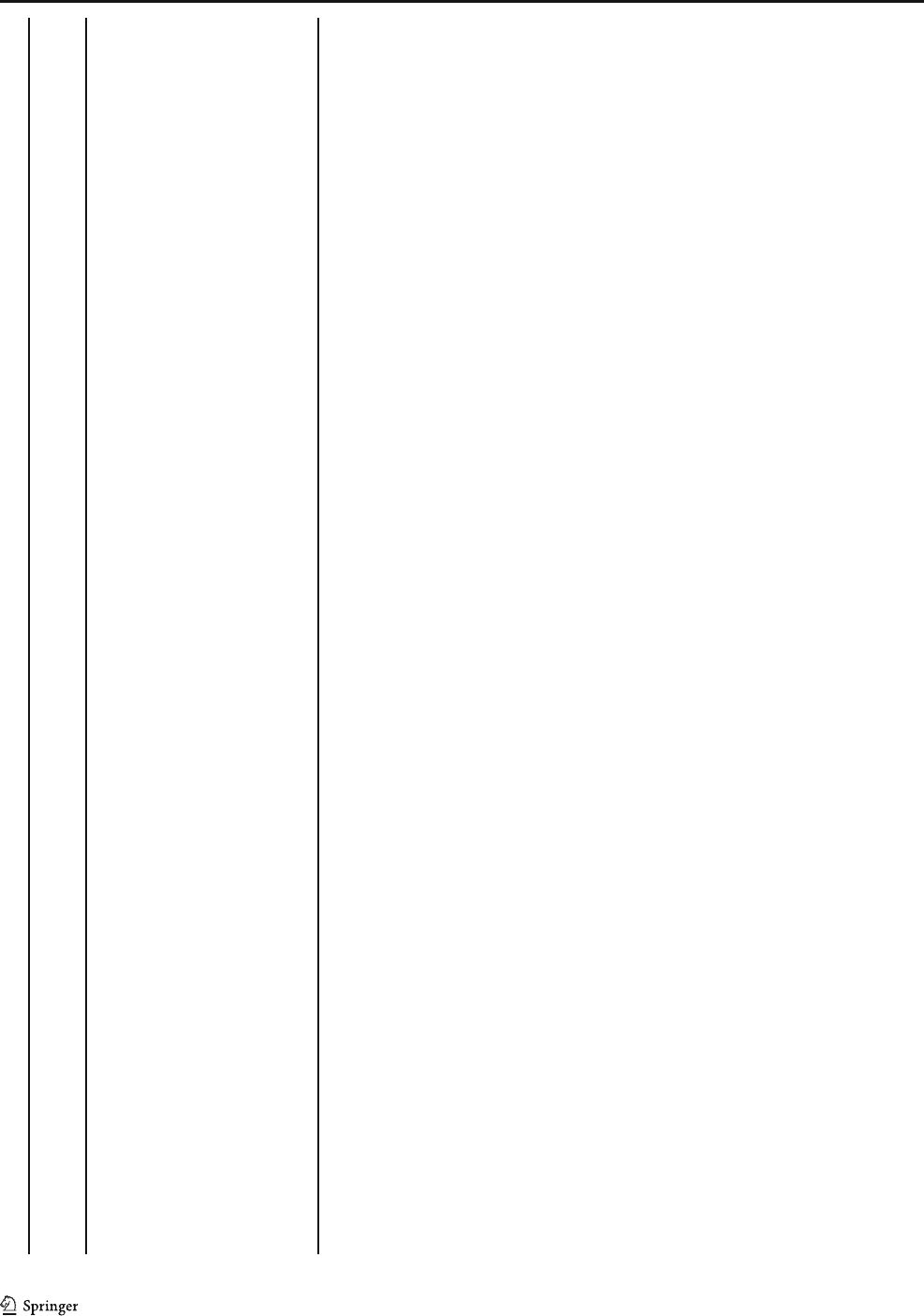

The methodological quality assessment by the PEDro scale

revealed a median score of 5 (range 4–6) (Table 1). Random

allocation, adequate follow-up, between-group comparisons

and point estimates and variability were included in all trials.

Concealed allocation, blind subjects, blind therapists and

blind assessors were not included in all trials. Comparability

at baseline was included in three trials [19, 20, 22]. Intention-

to-treat analysis was reported in two publications [19, 20].

The articles included in this review investigated telehealth

in the treatment of stress urinary incontinence (SUI) and urge

urinary incontinence. Only two studies were original random-

ized controlled trials [19, 22]. The other two publications were

a follow-up [20] and cost analysis [21] of the study developed

by Sjostrom et al. [19]. The details of the studies are described

in the Table 2.

Int Urogynecol J

Telehealth—How is it performed?

The studies included in this review investigated the internet-

based program versus postal program [19–21] and conven-

tional treatment (face-to-face intervention) [22].

In Sjostrom et al.’s study, the patients were recruited via an

open access website. Invitations to the study were published on

national websites for medical advice and as advertisements in

daily newspapers. To confirm the clinical diagnosis of SUI, all

participants were interviewed via telephone. The contact with

patients during the intervention was asynchronous, with

encrypted e-mail, requiring a separate login from b oth partici-

pants and therapists. The therapist gave the participant login

codes for two levels at a time, with instructions to maintain

training at each level for at least 1 week. The participants com-

pleted a self-evaluated test and reported a training diary to the

therapist weekly. New login codes were given with the passing

of every other test. The participants could contact their therapist

at any time for support or questions. Response from the thera-

pist was promised within 3 working day s, and sep arate

technical support was offered through encrypted e-mail contact

with the website manager. The program was built on a secure

platform, using a two-factor authentication and Secure Sockets

Layer (SSL) to provide communication security over the inter-

net. All parts of the program could be downloaded for printing

[19]. In this study, the authors compared telehealth with an

exercise program sent by post. The patients received a print

version containing information about the program, followed

by instructions for PFM training. The participants in this group

had no contact with the urotherapists [19].

Hui et al. performed the PFM program via videoconferenc-

ing. The sessions were carried out in a private and quiet room

in the community center. Subjects were reassured that they

were only sharing the progress of their incontinence symp-

toms with other participants in the session. The nurse special-

ist provided behavioral training to the group via videoconfer-

encing with the support of a research assistant at the patients’

end. The patients shared their experiences with the nurse and

were encouraged to adhere to behavioral training and PFM

exercises [22].

Records idenfied through database

searching

Medline/PubMed= 668

LILACS= 17

PEDro= 28

Total aer removing duplicates (n= 703)

Screening

Included

Eligibility

Idenficaon

Addional records idenfied through

other sources

(n= 0)

Records aer duplicates removed

(n= 705)

Records screened

(n= 8)

Records excluded aer

reading tle and abstract

(n= 697)

Full-text arcles assessed

for eligibility

(n= 8)

Full-text arcles excluded,

with reasons (n= 4)

The studies invesgated

the mobile device

(smartphone) to treat

pelvic floor dysfuncons

15-

18

Arcles included in this

review

(n= 4)

Fig. 1 PRISMA flow diagram for

the selected studies

Int Urogynecol J

Effects of telehealth on PFM function, urinary

symptoms and quality of life

Three articles from the same Swe dish group showed the

findings of a program for SUI treatment via the internet

versus by post on the same cohort of 250 women [19–21].

One publication presented the results on urinary symptoms,

cure and quality of life after 4 months of treatment using

questionnaires sent by post mail [19]; another publication

reported the same outcomes at 1- and 2-year follow-up

[20]; the last article addressed the costs of the two interven-

tions [21].

Sjostrom et al. [19] described significant improve-

ments in both i nterventions (internet and postal groups)

after ITT analysis, but there were no significant differ-

ences between groups in urinary symptoms and

condition-specific quality of life after 4-month treatment.

Regarding subjective cure, more participants in the i nter-

net group reported being much or very much improved

( p = 0.01), had reduced use of incontinence pads (p =

0.02) and were satisfied with the treatment program

(p < 0.001) compared to t he postal group. Quality of life

improved in the internet group (p = 0.001), but not in the

postal group (p = 0.13). Overall, 69.8% (120/172) o f the

participants reported absence or reduced number of UI

episodes by > 50% [19]. Loss to follow- up rate was 12% .

The authors report 32% loss of participants at 1-year and

38% at 2- year follow-up assessments. Highly significant

(p < 0.001) improvements were observed f or symptoms

and condition-specific quality of life after 1 and 2 years,

respectively, for both internet and postal interventions, with-

out significant differences between groups. The proportions

of participants perceiving they were much or very much

improved were similar in both intervention groups after

1year(p = 0.82), but after 2 years significantly more partic-

ipants in the internet group reported this degree of improve-

ment (p = 0.03). At 1 year after treatment, 69.8% of partici-

pants in the internet group and 60.5% of participants in the

postal group reported that they were still satisfied with the

treatment result. After 2 years, the proportions were 64.9%

and 58.2%, respectively [20].

The authors measured quality of life w ith the ICIQ-

LUTSqol condition-specific questionnaire and calculated

the quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) gained to estimate

the cost-effectiveness. Compared to the postal program, the

extra cost per QALY for the internet-based program ranged

from 200€ to 7.253€, indicating greater QALY gains at sim-

ilar or slightly higher costs. Compared to no treatment, the

extra cost per QALY for the internet-based program ranged

from 10.022€ to 38.921€, indicating greater QALY gains at

higher but probably acceptable costs. The authors concluded

that an internet-based treatment for SUI is a new, cost-

effective treatment alternative [21].

Table 1 PEDro scale for the methodological quality assessment

Study Eligibility 1. Random

allocation

2. Concealed

allocation

3. Baseline

comparability

4. Blind

subjects

5. Blind

therapists

6. Blind

assessors

7. Adequate

follow-up

8. Intention-to-

treat analysis

9. Between-group

comparisons

10. Point estimates

and variability

Total

Score

Sjostrom

et al., 2013

[19]

++ – + –– – ++ + + 6

Sjostrom

et al., 2015

[20]

++ – + –– – ++ + + 6

Sjostrom

et al.,2015

[21]

++ –– –––+ – ++ 4

Hui et al., 2006

[22]

++ – + –– – + – ++ 5

Eligibility criteron item does not contribute to the total score; + criterion is clearly satisfied; − criterion is not satisfied

Int Urogynecol J

Table 2 Details of the included randomized controlled trials

Reference Study design/

period/country

Participant characteristics, sample size

(N), duration of symptoms

Interventions Outcomes (measures) and time points;

results; conclusion

Sjostrom

et al.,

2013

[19]

RCT/December

2009 to April

2011/

Sweden

Age = 18–70 years

N =250

Duration of symptoms = SUI ≥ 1

time/week

Inclusion

criteria = community-dwelling

women with SUI at least once a

week that matched with age. Ability

to read and write Swedish and sccess

to computer with internet

connection

Exclusion criteria = pregnancy,

previous incontinence surgery,

known malignancy in lower

abdomen, difficulties passing urine,

macroscopic hematuria,

intermenstrual bleedings, severe

psychiatric diagnosis, and

neurological disease affecting

sensibility in legs or lower abdomen

Dropout rate = 32.4%

Internet-based group = information on

SUI and associated lifestyle factors;

PFMT; training reports (frequency,

time spent). This group received

asynchronous, individually tailored

e-mail support from a urotherapist

during the treatment period

Postal group = information on SUI and

associated lifestyle factors; PFMT;

training reports (frequency, time

spent). Participants in this group had

no contact with the urotherapists

Follow-up: 4 months via self-assessed

postal questionnaires

Primary outcomes = International

Consultation on Incontinence

Questionnaire Short Form (ICIQ-UI

SF); International Consultation on

Incontinence Questionnaire Lower

Urinary Tract Symptoms Quality of

Life (ICIQ-LUTSQoL)

Secondary outcomes = Patient Global

Impression of Improvement (PGI-I);

urinary incontinence aids; patient

satisfaction; EuroQol 5D-Visual

Analogue Scale (EQ5D-VAS); in-

continence episode frequency (IEF)

Results = intention-to-treat analysis

showed high significance with both

interventions, but there were no

significant differences between

groups in primary outcomes. 40.9%

of internet group perceived they

were much or very much improved;

59.5% reported reduced usage of

incontinence aids; 84.8% were

satisfied with the treatment program

vs. 26.5%; 41.4% and 62.9%,

respectively, of postal group

Conclusion = Concerning primary

outcomes, treatment effects were

similar between groups whereas for

secondary outcomes the

internet-based treatment was more

effective. Internet-based treatment

for SUI is a new, promising treat-

ment alternative

Sjostrom

et al.,

2015

[20]

Follow-up was performed after 1 and

2 years via self-assessed postal

questionnaires

There was no face-to-face contact with

the participants at any time

Results = Within both treatment

groups, there were highly significant

improvements in the primary

outcomes, ICIQ-UI SF and

ICIQ-LUTSqol, after 1 and 2 years

compared with the baseline. The

difference between the groups was

not significant after 1 year. After

2 years, significantly more partici-

pants in the internet group rated their

leakage as much or very much im-

proved than was the case in the

postal group. Health-specific QoL

did not improve significantly in any

of the treatment groups after 1 year.

However, after 2 years there was

significant improvement within the

internet group, but not within the

postal group. The differences be-

tween the groups were not signifi-

cant

Conclusion = Non-face-to-face

treatment of SUI with PFMT

provides significant and clinically

relevant improvements in symptoms

and condition-specific QoL at 1 and

2 years after treatment

Int Urogynecol J

Table 2 (continued)

Reference Study design/

period/country

Participant characteristics, sample size

(N), duration of symptoms

Interventions Outcomes (measures) and time points;

results; conclusion

Sjostrom

et al.,

2015

[21]

Included all relevant costs accrued

during the first year, regardless of

who paid for them. Prices per unit

were multiplied by the amount

consumed and added up to a sum

representing the total societal cost.

All costs are given in euros at the

2010 mid-year level

Follow-up = 1 year

Outcomes = incremental cost

effectiveness ratio (ICER);

International Consultation on

Incontinence Questionnaire Short

Form (ICIQ-UI SF); International

Consultation on Incontinence

Questionnaire Lower Urinary Tract

Symptoms Quality of Life

(ICIQ-LUTSQoL); quality-adjusted

life-years (QALYs).

Results = compared to the postal

program, the extra cost per QALY

for the internet-based program

ranged from 200€ to 7253€,indi-

cating greater QALY gains at simi-

lar or slightly higher costs.

Compared to no treatment, the extra

cost per QALY for the

internet-based program ranged from

10,022€ to 38,921€, indicating

greater QALY gains at higher, but

probably acceptable costs

Conclusion = an internet-based treat-

ment for SUI is a new, cost-effective

treatment alternative

Hui et al.,

2006

[22]

RCT/not

reported/

China

Age = 60 years or over

N =58

Inclusion

criteria = community-dwelling older

women aged 60 years or over, with

symptoms of urge or SUI, and with

one or more incontinence episodes

in a week

Exclusion criteria = active urinary tract

infection, a post-void residual vol-

ume by bladder ultrasound >

150 ml, third-degree uterine pro-

lapse and those already receiving

treatment for their urinary symptoms

Telemedicine continence group

(TCP) = 8-week intervention period

with one session per week by

videoconferencing

Continence service (CS) = 8-week

intervention period with one session

per week face to face

At baseline, both groups were assessed

face to face for pelvic floor muscle

strength, instrumental biofeedback

and verbal feedback by vaginal

palpation.

During the intervention period, all

components of behavioral training

given to either intervention group

were identical, with one exception in

the TCP group, where it was not

possible for the nurse specialist to

give feedback on pelvic floor

contraction during follow-up, as

digital assessment could not be

performed

Outcomes = perception of the severity

of incontinence symptoms and level

of satisfaction (0 = none, 1 = mild,

2 = moderate, 3 = severe); 3-day

voiding diary (number of inconti-

nent episodes, voiding frequency

and voided volume); pelvic floor

muscle strength by digital assess-

ment [Oxford Scale (0 = none, 1 =

flicker, 2 = weak, 3 = moderate, 4 =

good, 5 = strong)]; satisfaction with

the TCP on a 6-point Likert scale

(0 = highly dissatisfied to 5 = highly

satisfied).

Results = participants in both treatment

groups experienced significant

improvement in their symptoms

with a reduction in the number of

daily incontinence episodes and

voiding frequency, while the

volume of urine at each micturition

increased. Pelvic floor muscle

strength also improved. There were

no significant differences in

outcomes between the two groups

Conclusion = results suggested that

videoconferencing is as effective as

conventional methods in the

management of urinary incontinence

PFMT pelvic floor muscle training,

SUI stress urinary incontinence, ICIQ-UI SF International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire Short Form,

ICIQ-LUTSqol International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Quality of Life, PGI-I Patient Global

Impression of Improvement, EQ5D-VAS EuroQol 5D-Visual Analogue Scale, IEF incontinence episode frequency, ICER incremental cost effectiveness

ratio, QALYs quality-adjusted life-years, TCP telemedicine continence group, CS continence service

Int Urogynecol J

Hui et al. compared telemedicine with conventional outpa-

tient sessions (face to face) in 58 community-dwelling older

women with urgency or SUI. There were no significant dif-

ferences in outcomes between the two groups. Participants in

both treatment groups experienced significant improvement in

their symptoms, namely, reduction in the number of daily

incontinence episodes (p < 0.001) and voiding frequency (p

< 0.001), while the volume of urine at each micturition in-

creased (p < 0.005). PFM strength as measured by the

Oxford Scale also improved (p <0.005)[22].

Discussion

Telehealth is an alternative way to provide rehabilitation ser-

vices. Technological advances prove to be a facilitator in the

communication between the health professional and the pa-

tient especially in remote locations, presenting great potential

as a substitute or as a complement to current therapies [23].

Digital practice is not a modality used in all countries and

depends on the local regulations.

The main question is how to use digital technology in the

clinical practice of PFM rehabilitation. In this review we gath-

ered data from two controlled trials that addressed

teleconsultation and telemonitoring in the rehabilitation of

PFM for the treatment of urinary disorders [19–22].

Sjostrom et al. used a PFMT program via the internet com-

pared to a postal program. For the authors a standardized face-

to-face treatment or care as usual would have been an option

to compare the internet modality, but they wanted the treat-

ment program to be accessible to women from all over the

country, even from remote areas or from areas with inadequate

staffing [19]. Both modalities were shown to be beneficial

treatments after 4-month intervention [19] and at 1 and 2 years

after treatment [20]; thus, management of SUI without face-

to-face contact is possible and may increase access to care.

The authors also found the internet-based treatment is an ef-

fective new, promising, alternative treatment [19, 20].

Before starting a PFM training program, one has to ensure

that the patients are able to perform a correct PFM contraction

[6]. In the study developed by Sjostrom et al., all the interven-

tions were made without PFM evaluation. The authors did not

explain how the patients were directed to perform the PFM

contraction, but they acknowledged that the ability to under-

stand written instructions, carry them out and adequately use a

computer were prerequisites to succeed with a treatment com-

pleted on one’s own in the internet group [19].

On the other hand, Hui et al. assessed the PFM strength

face to face with biofeedback (BF) and vaginal palpation at

baseline in both groups (telemedicine continence group and

conventional group) in their study [22]. The literature suggests

the utilization of sensor technologies to sample and quantify

movement in telehealth [24]. BF equipment uses sensors to

measure PFM contraction and maybe can be used in

telehealth. There is no consensus in the literature on whether

BF can be used to promote awareness of the PFM. Some

authors have tried to make patients more aware of muscle

function [25]. To date, there are no studies investigating the

effect of BF in a population that is not able to contract the

PFM. In others’ opinions, it is difficult to understand how the

BF machine can teach the patient how to contract the PFM

without verbal instruction and manual techniques explained

by the therapist [26].

Conservative treatment depends heavily on physical touch,

and therapists rely on the objective measurement of physical

performance to inform diagnosis and intervention [24]. With

this, therapies that do not typically involve hands-on assess-

ment are best suited to digital practice. Even though in PFM

rehabilitation it is difficult to adapt the practice to provide

services via information and communication technologies, as

hands-on assessment and treatment are typically involved, it

seems that it is feasible to teach the correct PFM contraction

technique with verbal instructions and drawings of the anato-

my of the pelvic floor and to help the patients understand the

action of the PFM, describing the contraction as a lift starting

with closure of the doors (squeeze) and from there the elevator

is moving upstairs (lift) [6].

The virtual environment can be displayed to the patient via

computer screen, or fully immersive environments are possi-

ble with the use of head-mounted visual displays and feedback

devices [24]. Sjostron et al. used a program developed on a

secure platform with two-factor authentication [19]. Hui et al.

used videoconferencing, and participants shared their experi-

ences with the group members. The only request was that the

patients remain in a private and silent room [22]. A private

environment, with the use of headphones so that other profes-

sionals and/or family members do not have access to the ses-

sion, should be recommended. The risk of leakage of infor-

mation related to digital care always exists and must be shared

with patients, and, whenever possible, safer professional plat-

forms should be used [27].

The patient’s knowledge and ability related to the virtual

environment must be considered. Some patients considered

the double logins complicated in the study of Sjostrom et al.

[19]. Therefore, it is recommended that service providers en-

sure that technical requirements are met, provide access to

technical support and provide training to all users [23]. The

lack of ability and knowledge related to handling technologies

are the disadvantages of telerehabilitation [28].

The literature reports that the savings of transportation

costs and of the health care system’s and patient’s time, the

continuity of patient care that can be achieved through the

remote provision and the heightened abil ity to control the

timing, intensity and sequencing of the intervention are advan-

tages of telerehabilitation [24]. The questions are whether the

professionals are prepared to implement digital practice and

Int Urogynecol J

how they can offer telerehabilitation services, especially in the

area of pelvic floor dysfunction rehabilitation. This type of

service is a growing field, adopted within the COVID-19 pan-

demic, and has the potential to reduce costs, increase the over-

all accessibility of modern health care systems and open new

perspectives for rehabilitation in pelvic floor dysfunctions [2,

29]. A guide with specific issues involving digital practice in

physical therapy needs to developed. And the governmental

authorities, physical therapy councils and corresponding asso-

ciations of each country should be involved.

The limitations of this study include the scarcity of litera-

ture related to telehealth, especially compared to conventional

treatment (face to face). The study performed by Hui et al. was

the only one that compared telehealth with conventional treat-

ment. The authors concluded that telehealth is as effective as

conventional treatment for urinary incontinence [22]. The lit-

erature reports on telehealth and conventional treatment in

other fields of medicine that require conservative therapy.

As with all fields and interventions, effective telehealth re-

quires that therapists understand the essential components of

their treatments and ensure that they are carefully included in

care [28, 29]. Thus, because of the specificity of each field, it

is not possible to discuss the results found by Hui et al. with

further scientific depth. Another limitation is the fact that the

review was carried out in a short period, limiting the search in

the gray literature, and the article was produced quickly so that

it could be useful to professionals and patients.

Conclusion

The literature on digital practice in the treatment of pelvic

floor dysfunction is scarce. Only two original studies have

investigated telehealth in SU I treatment, and one of them

was without a face-to-face group. Telehealth promoted a sig-

nificant improvement in urinary symptoms, PFM function and

quality of life. The results of the studies showed that internet-

based treatment is a promising treatment alternative.

However, this type of assistance still needs to be studied to

verify its real benefits in the treatment of pelvic floor dysfunc-

tions, since further clarification is needed on how to perform

it. The recommendations of governmental authorities, physi-

cal therapy councils and corresponding associations of each

country also need to be considered.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations COVID-19, Coronavirus Disease 2019; PFM, Pelvic

floor muscle; PFMT, Pelvic floor muscle training; PEDro,

Physiotherapy Evidence Database; SUI, Stress urinary incontinence

Appendix

PEDro: Telerehabiltation AND Continence and women’s

health; Tele AND Continence and women’s health; Video

conferecing AND Continence and women’s health; Internet

AND Continence and women’shealth.

LILACS: Telerehabilitation AND Pelvic Floor;

Telerehabilitation AND Telehealth AND Women’s Health;

Videoconferencing AND Pelvic Floor; videoconfe rencing

AND Urinary Incontinence (tw:(Pelvic Prolapse)) AND

(tw:(telerehabilitation)); (tw:(telerehabilitation)) AND

(tw:(telehealth)) AND (tw:(women’ s health)) AND

(tw:(Pelvic Prolapse)); (tw:(women’s health)) AND

(tw:(Pelvic Prolapse)) AND (tw:(Video Virtual));

(tw:(Videoconferencing)) AND (tw:(Pelvic Prolapse));

(tw:(Videoconferencing)) AND (tw:(fecal incontinence));

(tw:(Video Virtual)) AND (tw:(fecal incontinence));

(tw:(telerehabilitation)) AND (tw:(women’shealth))AND

(tw:(fecal incontinence)).

PubMed: ((Internet) AND Continence) AND Women’s

Health; (Tele) AND Pelvic Floor; (Internet) AND Pelvic Floor;

(((Telerehabilitations) OR (Tele-rehabilitation) OR (Tele rehabil-

itation) OR (Tele-rehabilitations) OR (Remote Rehabilitation)

OR (Rehabilitation, Remote) OR (Rehabilitations, Remote) OR

(Remote Rehabilitations) OR (Virtual Rehabilitation) OR

(Rehabilitation, Virtual) OR (Rehabilitations, Virtual) OR

(Virtual Rehabilitations) OR)) AND Pelvic Floor; (Video

Conferencing) AND Pelvic Floor; (Video Conferencing) AND

Pelvic Floor; (((((Telehealth) AND Women ’s Health)) AND

((Telerehabili tation) OR (Tele-rehabili tation) OR (Tele rehabi li-

tation) OR (Tele-rehabilitations) OR (Remote rehabilitation) OR

(Rehabilitation, remote) OR (Rehabil itation s, remote) OR

(Remote rehabilitations) OR (Virtual rehabilitation) OR

(Rehabilitation, virtual) OR (Rehabilitations, virtual ) OR

(Virtual rehabilitations)))) AND ((Video conferencin g) AND

Pelvic floor muscle dysfunction); (((((Telehealth) AND

Women’s health)) AND ((telerehabi litation) OR (t ele-

rehabilitation) OR (tele rehabilitation) OR (tele-rehabilitations)

OR (remote rehabilitation) OR (rehabilitation, remote) OR (reha-

bilitations, remote) OR (remote rehabilitations) OR (virtual reha-

bilitation) OR (rehabilitation, virtual) OR (rehabilitations, virtual)

OR (virtual rehabilitations)))) AND ((vide o conferencing) AND

pelvic floor muscle dysfunction); (((teleheal th) AND women’s

health)) AND ((telerehabilitation) OR (tele-rehabilitation) OR

(tele rehabilitation) OR (tele-rehabilitations) OR (remote rehabil-

itation) OR (rehabilitation, remote) OR (rehabilitations, remote)

OR (remote rehabilitations) OR (virtual rehabilita tion) OR (reha-

bilitation, virtual) OR (rehabilitations, virtual) OR (virtual reha-

bilitations)); (telehealth) AND women’ s health;

(((((telerehabilitation) OR (tele-rehabilitation) OR (tele rehabili-

tation) OR (tele-rehabilitations) OR (remote rehabilitation) OR

(rehabilitation, remote) OR (rehabilitations, remote) OR (remote

rehabilitations) OR (virtual rehabilitation) OR (rehabilitation,

Int Urogynecol J

virtual) OR (rehabilitations, virtual) OR (virtual rehabilitations)))

AND Women’s health)) AND telehealth; (video conferencing)

AND pelvic floor muscle dysfunction; (video conferencing)

AND pelvic floor muscle dysfunction; ((((Telerehabilitations)

OR (Tele-rehabilitation) OR (Tele rehabilitation) OR (Tele-

rehabilitations)OR (Remote Rehabilitation) OR (Rehabilitation,

Remote) OR (Rehabilitations, Remote) OR (Remote

Rehabilitations) OR (Virtual Rehabilitation) OR

(Rehabilitation, Virtual)OR (Rehabil itations, Virtual) OR

(Virtual Rehabilitations) OR)) AND video conferencing) AND

((((telerehabilitation) OR (tele-rehabilitation) OR (tele rehabilita-

tion) OR (tele-rehabilitations) OR (remote rehabilitation) OR (re-

habilitation, remote) OR (rehabilitations, remote) OR (remote

rehabilitations) OR (virtual rehabilitation) OR (rehabilitation, vir-

tual) OR (rehabilitations, virtual) OR (virtual rehabilitations)))

AND pelvic floor muscle dysfunction); ((((Telerehabilitations)

OR (Tele-rehabilitation) OR (Tele rehabilitation) OR (Tele-

rehabilitations)OR (Remote Rehabilitation) OR (Rehabilitation,

Remote) OR (Rehabilitations, Remote) OR (Remote

Rehabilitations) OR (Virtual Rehabilitation) OR

(Rehabilitation, Virtual)OR (Rehabil itations, Virtual) OR

(Virtual Rehabilitations) OR)) AND video conferencing) AND

((((telerehabilitation) OR (tele-rehabilitation) OR (tele rehabilita-

tion) OR (tele-rehabilitations) OR (remote rehabilitation) OR (re-

habilitation, remote) OR (rehabilitations, remote) OR (remote

rehabilitations) OR (virtual rehabilitation) OR (rehabilitation, vir-

tual) OR (rehabilitations, virtual) OR (virtual rehabilitations)))

AND pelvic floor muscle dysfunction); (((telerehabilitation)

OR (t ele-rehabilitation) OR (tele rehabilitation) OR (tele-

rehabilitations) OR (remote rehabilitation) OR (rehabilitation, re-

mote) OR (re habilitations, remote) OR (remote rehabilitations)

OR (virtual rehabilitation) OR ( rehabilitation, virtual) OR (reha-

bilitations, virtual) OR (virtual rehabilitations))) AND pelvic

floor muscle dysfunction; (((telerehabilitation) OR (tele-

rehabilitation) OR (tele rehabilitation) OR (tele-rehabilitations)

OR (remote rehabilitation) OR (rehabilitation, remote) OR (reha-

bilitations, remote) OR (remote rehabilitations) OR (virtual reha-

bilitation) OR (rehabilitation, virtual) OR (rehabilitations, virtual)

OR (virtual rehabilitations))) AND sexual dysfunction;

(((telerehabilitation) OR (tele-rehabilitation) OR (tele rehabilita-

tion) OR (tele-rehabilitations) OR (remote rehabilitation) OR (re-

habilitation, remote) OR (rehabilitations, remote) OR (remote

rehabilitations) OR (virtual rehabilitation) OR (rehabilitation, vir-

tual) OR (rehabilitations, virtual) OR (virtual rehabilitations)))

AND pelvic pain; (((telerehabilitation) OR (tele-rehabilitation)

OR (tele rehabilitation) OR (tele-rehabilitations) OR (remote re-

habilitation) OR (rehabilitation, remote) OR (rehabilitations, re-

mote) OR (remote rehabilitations) OR (virtual rehabilitation) OR

(rehabilitati on, virtual) OR (rehabilitations, virtual) OR (virtual

rehabilitations))) AND urinary incontinence; (((telerehabilitation)

OR (t ele-rehabilitation) OR (tele rehabilitation) OR (tele-

rehabilitations) OR (remote rehabilitation) OR (rehabilitation, re-

mote) OR (re habilitations, remote) OR (remote rehabilitations)

OR (virtual rehabilitation) OR ( rehabilitation, virtual) OR (reha-

bilitations, virtual) OR (virtual rehabilitations))) AND Women’s

health; telerehabilitation) OR (tele-rehabilitation) OR (tele reha-

bilitation) OR (tele-rehabilitations) OR (remote rehabilitation)

OR (rehabilitation, remote) OR (rehabilitations, remote) OR (re-

mote rehabilitations) OR (virtual rehabilitation) OR (rehabilita-

tion, virtual) OR (rehabilitations, virtual) OR (virtual rehabilita-

tions) Telerehabilitation[MeSH Terms]Pelvic Prolapse;

(((((((Telehealth) AND Women’ s health)) AND

((telerehabilitation) OR (tele-rehabilitation) OR (tele rehabilita-

tion) OR (tele-rehabilitations) OR (remote rehabilitation) OR (re-

habilitation, remote) OR (rehabilitations, remote) OR (remote

rehabilitations) OR (virtual rehabilitation) OR (rehabilitation, vir-

tual) OR (rehabilitations, virtual) OR (virtual rehabilitations))))

AND ((v ideo confe rencing) AND pelvic floor muscle dysfunc-

tion))) AND (Pelvic Prolapse[MeSH Terms]); (((Pelvic

Prolapse) AND (Tele)) AND (Telerehabilitation[MeSH

Terms])) AND (Internet[MeSH Terms]); (telehealth) AND

women’s health; (((((telerehabilitation) OR (tele-rehabilitation)

OR (tele rehabilitation) OR (tele-rehabilitations) OR (remote re-

habilitation) OR (rehabilitation, remote) OR (rehabilitations, re-

mote) OR (remote rehabilitations) OR (virtual rehabilitation) OR

(rehabilitati on, virtual) OR (rehabilitations, virtual) OR (virtual

rehabilitations))) AND Women’s health)) AND telehealth; (vid-

eo conferencing) AND pelvic floor muscle dysfunction AND

Pelvic Prolapse; (((Telerehabilitations) OR (Tele-rehabilitatio n)

OR (Tele rehabilitation) OR (Tele-rehabilitations)OR (Remote

Rehabilitation) OR (Rehabilitation, Remote) OR

(Rehabilitations, Remote) OR (Remote Rehabilitations) OR

(Virtual Rehabilit ation) OR (Rehabilitation, Vi rtual)OR

(Rehabilitations, Virtual) OR (Virtual Rehabilitations) OR))

AND Pelvic Floor AND Pelvic Prolapse; Telerehabilitation

AND Internet AND Fecal Incontinence; Fecal incontinences

AND Tele; (((Telerehabilitations) OR (Tele-rehabilitation) OR

(Tele rehabilitation) OR (Tele-rehabilitations)OR (Remote

Rehabilitation) OR (Rehabilitation, Remote) OR

(Rehabilitations, Remote) OR (Remote Rehabilitations) OR

(Virtual Rehabilit ation) OR (Rehabilitation, Vi rtual)OR

(Rehabilitations, Virtual) OR (Virtual Rehabilitations) OR))

AND Pelvic Floor AND tele AND fecal incontinence;

Women’s Health AND Videoconferencing AND fecal

Incontinence; Fecal Incontinence AND in ternet.

EMBASE.

(Physioterapy OR Telerehabilitation) AND Women’S

AND Health AND ‘Sexual Dysf unction ’; (Physio AND

Terapy OR Telerehabilitation)AND Women’S AND Health

AND ‘Sexual Dysfunction’; (Physio AND Terapy OR

Telerehabilitation) AND Women’S AND Health AND

Urinary AND Incontinence; (Telerehabilitation OR Tele)

AND Women’ S AND Health AND Urinary AND

Incontinence;Physical AND Therapy AND

Telerehabilitation AND Women’S AND Health AND

Urinary AND Incontinence; Telerehabilitation AND Internet

Int Urogynecol J

AND Urinary AND Incontinence AND ‘Women’SHealth’;

Telerehabilitation AND Tele AND ‘Urine Incontinence’

AND ‘Women’S Health’; Telerehabilitation AND Tele

AND ‘ Pelvic Floor’ AND ‘ Women’ SHealth’ ;

Telerehabilitation AND Tele AND Pelvic AND Organ AND

Prolapse AND ‘Women’S Health’; Telerehabilitation AND

Tele AND Incontinence AND Urinary; (‘Telerehabilitation’/

Exp OR Telerehabilitation) AND Tele AND Continence;

(‘Videoconferencing’/Exp OR Videoconferencing) AND

Tele AND Pelvic AND Floor; Tele AND Sexual AND

Dysfunction AND Videoconferencing; (‘Telerehabilitation’/

Exp OR Telerehabilitation) AND Sexual AND Dysfunction

AND Videoconferencing; (‘Telehealth’/Exp OR Telehealth

OR Telerehabilitation:Ti) AND ‘Womens Health’ AND

‘ Pelvic Floor’ ;(‘ Videoconferencing’ /Exp OR

Videoconferencing) AND ‘Womens Health’ AND ‘Pelvic

Floor’;(‘Videoconferencing’/Exp OR Videoconferencing)

AND ‘ Womens Health’ AND ‘ Pelvic Floor’ ;

Telere habilitation AND ‘Muscle Dysfunction’ AND Tele;

Telerehabilitation AND Fecal AND Incontinence AND Tele

AND ‘Women’SHealth’; Telerehabilitation AND Tele AND

‘Women’SHealth’ AND Pelvic AND Pain; Telerehabilitation

AND Telehealth AND ‘Women’S Health’ AND Pelvic AND

Pain; (‘Vide oconferencing’/Exp OR Videoconferencing)

AND Telerehabilitation AND ‘Womens Health’ AND

‘Pelvic Floor’ ;(‘Internet’ /Exp OR Internet) AND

Telerehabilitation AND ‘Womens Health’ AND ‘Pelvic

Floor’;(‘Telerehabilitation’/Exp OR Telerehabilitation)

AND Telerehabilitation AND ‘Womens Health’ AND

‘ Pelvic Floor’ ;(‘ Telerehabilitation’ /Exp OR

Telerehabilitation) AND Telerehabilitation AND ‘Womens

Health’ AND ‘Pelvic Floor’;(‘Telerehabilitation’/Exp OR

Telerehabilitation) AND ‘ Womens Health’ ;

(‘Telerehabilitation’/E xp OR Telerehabi litation) AND

‘Pelvic Floor’;(‘Pelv ic Floo r’/Exp OR ‘Pelvic Floor’ OR

((‘ Pelvic’ /Exp OR Pelvic) AND Floor)) AND

Telerehabilitation

References

1. Digital Practice White Paper and Survey. http://www.inptra.org/

Resources/DigitalPracticeWhitePaperandSurvey.aspx. Accessed

30 April, 2020.

2. Dantas LO, Barreto RPG, Ferreira CHJ. Digital physical therapy in

the COVID-19 pandemic [published online ahead of print, 2020

May 1]. Braz J Phys Ther. 2020;S1413–3555(20):30402–0.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjpt.2020.04.006.

3. Chartered Society of Physiotherapy. Remote service delivery op-

tions. https://www.csp.org.uk/news/coronavirus/remote-service-

delivery-options. Accessed 30 April, 2020.

4. Canadian Physiotherapy Association. Tele-Rehabilitation. https://

physiotherapy.ca/telerehabilitation. Accessed 30 April, 2020.

5. Conselho Federal de Fisioterapia e Terapia Ocupacional

(COFFITO). Resolução No 516, de 20 de março de 2020 -

Teleconsulta, Telemonitoramento e teleconsultoria; 2020. https://

www.coffito.gov.br/nsite/?p=15825.Accessed30April,2020.

6. Bø K, Mørkved S. Ability to contract the pelvic floor muscles. In:

Bø K, Berg hmans B, Mørkved S , Van Kampen M, editors.

Evidence-based physical therapy for the pelvic floor. Edinburgh:

Elsevier; 2015. p. 110–7.

7. Kegel AH. Stress incontinence and genital relaxation; a nonsurgical

method of increasing the tone of sphincters and their supporting

structures. Ciba Clin Symp. 1952;4(2):35–51.

8. Bump R, Hurt WG, Fantl JA, Wyman JF. Assessment of Kegel

exercise performance after brief verbal instruction. Am J Obstet

Gynecol. 1991;165:322–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9378(91)

90085-6.

9. Castro RA, Arruda RM, Zanetti MR, Santos PD, Sartori MG, Girão

MJ. Single-blind, randomized, controlled trial of pelvic floor mus-

cle training, electrical stimulation, vaginal cones, and no active

treatment in the management of stress urinary incontinence.

Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2008;63(4):465–72. https://doi.org/10.1590/

s1807-59322008000400009.

10. Bø K, Hagen RH, Kvarstein B, Jørgensen J, Larsen S. Pelvic floor

muscle exercise for the treatment of female urinary stress inconti-

nence: III. Effects of two different degrees of pelvic floor muscle

exercises. Neurourol Urodyn. 1990;9:489–502. https://doi.org/10.

1002/nau.1930090505.

11. Fitz FF, Gimenez MM, de Azevedo Ferreira L, Matias MMP,

Bortolini MAT, Castro RA. Pelvic floor muscle training for female

stress urinary incontinence: a randomised control trial comparing

home and outpatient training. Int Urogynecol J. 2020;31(5):989–

98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-019-04081-x.

12. Felicíssimo MF, Carneiro MM, Saleme CS, Pinto RZ, da Fonseca

AM, da Silva-Filho AL. Intensive supervised versus unsupervised

pelvic floor muscle training for the treatment of stress urinary in-

continence: a randomized comparative trial. Int Urogynecol J.

2010;21(7):835–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-010-1125-1.

13. Bagg MK, McAuley JH. Correspondence: living systematic re-

views. J Phys. 2018;64(2):133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphys.

2018.02.015.

14. Sherrington C, Herbert RD, Maher CG, Moseley AM. PEDro. A

database of randomized trials and systematic reviews in physiother-

apy. Man Ther. 2000;5(4):223–6. https://doi.org/10.1054/math.

2000.0372.

15. Osborne LA, Whittall CM, Emanuel R, Emery S, MD DPPR.

Randomized controlled trial of the effect of a brief telephone sup-

port intervention on initial attendance at physiotherapy group ses-

sions for pelvic floor problems. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;98:

2247–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2017.03.033.

16. Carrión Pérez F, Rodríguez Moreno MS, Carnerero Córdoba L,

Romero Garrido MC, Quintana Tirado L, Garcí a Montes I.

Tratamiento de la incontinencia urinaria de esfuerzo mediante

telerrehabilitación. Estudio piloto [Telerehabilitation to treat stress

urinary incontinence Pilot study]. Med Clin (Barc). 2015;144(10):

445–

8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medcli.2014.05.036.

17. Kristjánsdóttir OB, Fors EA, Eide E, et al. A smartphone-based

intervention with diaries and therapis t-feedback to reduce

catastrophizing and increase functioning in women with chronic

widespread pain: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res.

2013;15(1):e5. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.2249.

18. Kristjánsdóttir ÓB, Fors EA, Eide E, et al. A smartphone-based

intervention with diaries and therapist feedback to reduce

catastrophizing and increase functioning in women with chronic

widespread pain. Part 2: 11-month follow-up results of a random-

ized trial. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(3):e72. https://doi.org/10.

2196/jmir.2442.

Int Urogynecol J