Vol.:(0123456789)

1 3

Theoretical and Applied Genetics

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00122-020-03727-5

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Genetic diversity ofEthiopian sorghum reveals signatures ofclimatic

adaptation

T.Menamo

1

· B.Kassahun

1

· A.K.Borrell

2

· D.R.Jordan

2

· Y.Tao

2

· C.Hunt

3

· E.Mace

2,3

Received: 18 May 2020 / Accepted: 6 November 2020

© Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature 2020

Abstract

Key message A large collection of Ethiopian sorghum landraces, characterized by agro-ecology and racial-group,

was found to contain high levels of diversity and admixture, with significant SNP associations identified for environ-

mental adaptation.

Abstract Sorghum [Sorghum bicolor L. (Moench)] is a major staple food crop in Ethiopia, exhibiting extensive genetic

diversity with adaptations to diverse agroecologies. The environmental and climatic drivers, as well as the genomic basis of

adaptation, are poorly understood in Ethiopian sorghum and are critical elements for the development of climate-resilient

crops. Exploration of the genome–environment association (GEA) is important for identifying adaptive loci and predicting

phenotypic variation. The current study aimed to better understand the GEA of a large collection of Ethiopian sorghum

landraces (n = 940), characterized with genome-wide SNP markers, to investigate key traits related to adaptation to tem-

perature, precipitation and altitude. The Ethiopian sorghum landrace collection was found to consist of 12 subpopulations

with high levels of admixture (47%), representing all the major racial groups of cultivated sorghum with the exception of

kafir. Redundancy analysis indicated that agroecology explained up to 10% of the total SNP variation, and geographical

location up to 6%. GEA identified 18 significant SNP markers for environmental variables. These SNPs were found to be

significantly enriched (P < 0.05) for a priori QTL for drought and cold adaptation. The findings from this study improve our

understanding of the genetic control of adaptive traits in Ethiopian sorghum. Further, the Ethiopian sorghum germplasm

collection provides sources of adaptation to harsh environments (cold and/or drought) that could be deployed in breeding

programs globally for abiotic stress adaptation.

Introduction

Sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L.[Moench]) is a staple food

crop for smallholder farmers in semiarid regions world-

wide, feeding over 500 million of the world’s most resource

poor (Reddy and Patil 2015). In Ethiopia, sorghum ranks

second after maize in total production (FAOSTAT 2017).

Sorghum, a tropical C4 cereal, is hypothesized to have been

first domesticated in Ethiopia around 8000years ago (House

1985), with a second domestication event thought to have

occurred in West Africa (Mace etal. 2013). It is a versatile

crop used for food, feed, fuel, building materials and alco-

holic beverages (Damon 1962; Paterson etal. 2009). Sor-

ghum is characterized more by diversity than homogeneity

(Blum 2004), with genotypes adapted to different combina-

tions of temperate and tropical climates, high and low alti-

tudes and water stress environments (Maunder 2002; Blum

2004). Specifically, it has developed a range of biochemical,

physiological and morphological adaptation characteristics

Communicated by Hai-Chun Jing.

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this

article (https ://doi.org/10.1007/s0012 2-020-03727 -5) contains

supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

* E. Mace

1

College ofAgriculture andVeterinary Medicine, Jimma

University, P.O. Box307, Jimma, Ethiopia

2

Queensland Alliance forAgriculture andFood Innovation

(QAAFI), Hermitage Research Facility, University

ofQueensland, Warwick, QLD4370, Australia

3

Department ofAgriculture andFisheries, Hermitage

Research Facility, Agri-Science Queensland, Warwick,

QLD4370, Australia

Theoretical and Applied Genetics

1 3

that contribute to enhancing grain productivity in hot and

dry environments (Borrell etal. 2006, 2020; Paterson etal.

2009). Adaptation to different agroecologies has led to the

evolution of morphologically and geographically distinct

racial groups within cultivated sorghum; bicolor, guinea,

caudatum, kafir and durra, with four of these five basic sor-

ghum types (the exception being kafir) distributed across

Ethiopia (DoggettandHawkes 1991). Durra, the dominant

botanical race in Ethiopia, is known for its adaptation to

drier zones and likely originated in Ethiopia before diffus-

ing westward along the Sahel to West Africa (Harlan and De

Wet 1972). Guinea types are found around the highlands in

southwest Ethiopia (DoggettandHawkes 1991) and exhibit

adaptation to humid zones (Deu etal. 1995; Folkertsma

etal. 2005). Caudatum types are more highly distributed in

the lowland areas of Ethiopia, and bicolor types are distrib-

uted more in high rainfall and highland areas of Ethiopia

(DoggettandHawkes 1991). Inflorescence morphology is a

major component of racial differentiation and agro climatic

adaptation in sorghum, with all five botanical races tradition-

ally identified by mature spikelet types (Harlan and De Wet

1972; House 1985), varying from loose panicle architecture

in guinea types to compact panicle architecture in durra

types (Brown etal. 2011).

Collections of Ethiopian sorghum have been found to

exhibit great genetic diversity (Poehlman 1987; Cuevas and

Prom 2013), and inter-crossable wild and landrace material

has been shown to be a major source of many biotic and

abiotic stress resistance traits (Hajjar and Hodgkin 2007).

However, the natural habitat for wild and landrace sorghum

in Ethiopia is rapidly declining due to increased cultivated

land, urbanization, grazing, introduction of elite varie-

ties and displacement with other crops. A recent study by

Teshome and Feyissa (2013) identified low gene diversity

among a small collection of landraces from East Wollega

and East Shewa in Ethiopia; however, the small sample size

may have contributed to further decreasing the extent of

genetic diversity identified in this study. Ayana etal. (2000)

also reported low genetic variation among 11 wild sorghums

in Ethiopia that were representative of 93 wild sorghum

individuals from five geographical regions of the country.

Another recent study (Adugna 2014) suggested that the

occurrence of drought in some of the major sorghum grow-

ing regions of Ethiopia has reduced the diversity of the crop

over time, with a tendency for farmers in the dry lowlands to

use high yielding improved early maturing sorghum varieties

or shift their production systems to other early maturing crop

species such as tef (Eragrostis tef).

Despite such reports of a potential reduction in diversity

in Ethiopian sorghums, there has been a steady increase

in average grain yield in Ethiopia due to the generation of

improved elite sorghum varieties and improved cultural prac-

tices over the past 10years (FAOSTAT 2017). The continued

exploration and utilization of genetic diversity are a vital

component of maintaining and increasing the rate of genetic

gain made in sorghum breeding programs in Ethiopia. Uti-

lizing genetic diversity also complements related research

and development activities, such as marker–trait association

studies, appropriate sampling procedures for germplasm col-

lection and conservation, and generating core collections

for efficient germplasm management (Moreno-Gonzalez

and Cubero 1993). Additionally, a number of recent studies

have focused on investigating the genetic diversity of culti-

vated Ethiopian sorghum conserved in different countries.

For example, selected Ethiopian accessions maintained by

the USA National Plant Germplasm System (NPGS) have

been genetically characterized using SNP markers (Cuevas

and Prom 2013; Morris etal. 2013; Cuevas etal. 2017),

with studies highlighting the genetically and phenotypically

diverse nature of the Ethiopian sorghum germplasm. These

studies did not, however, explore the patterns of genetic

variability observed in the Ethiopian collections at NPGS

in relation to geographic origin, and associated adaptation

environments. With a changing environment, marked by

increases in average global temperature and erratic pre-

cipitation patterns, an understanding of genetic diversity

distribution relative to environmental variance can provide

opportunities to identify sorghum landraces offering adap-

tive traits for crop improvement (Blum 2010).

Sorghum’s modest diploid genome (~ 730Mbp) compared

with other grass species makes it an ideal system for the

genomic studies of local adaptation (Paterson etal. 2009),

and three recent studies (Lasky etal. 2015; Faye etal. 2019;

Olatoye etal. 2018) have investigated GEA in diverse sor-

ghum populations. These studies identified adaptive loci

and predicted phenotypic variation in West African and

global agroecological zones, indicating that adaptation

to diverse agroecological conditions can be explained by

nucleotide variation. Lasky etal. (2015) identified that such

genome–environment associations reflected local adaptation

at two previously reported genes, Maturity1 and Tannin1

controlling photoperiod sensitive flowering and grain tan-

nins. Specifically, Ma1 was found to be significantly associ-

ated with the minimum temperature of the coldest month

and Tannin1 was found to be significantly associated with

the mean temperature of the warmest quartile. Olatoye etal.

(2018) studied GEA using three climatic variables (annual

mean precipitation, precipitation in the driest quarter and

annual mean temperature) and reported significant cor-

relations with three putative climate-adaptive traits (flow-

ering time, plant height and panicle length). To date, no

GEA studies have been reported in sorghum using altitude.

However, in addition to temperature and precipitation, alti-

tude has been identified as one of the factors determining

the sorghum race pattern distribution in Ethiopia (Stemler

etal. 1977). Another recent study by Wang etal. (2020)

Theoretical and Applied Genetics

1 3

reported that seed mass in sorghum is correlated with prox-

ies of precipitation gradients globally, suggesting that seed

mass is shaped by diversifying selection on drought stress. In

Ethiopia, there are two main cropping seasons: the Belg and

Meher (main) seasons which receive rainfall from February

to June and from June to October, respectively (Reynolds

2008). Some famers prefer late-maturing sorghum lan-

draces (long-cycle landraces), and in such cases, planting

takes place between April and May (to make use of both

rainy seasons), whereas some farmers prefer early maturing

landraces (short cycle landraces), and in these cases, plant-

ing is carried out in July (to make use of the Meher rainy

season) with the subsequent rains or residual soil moisture

(Gebretsadik etal. 2014). However, the genomic basis of

climate adaptation remains poorly understood in Ethiopian

sorghum germplasm. While the Ethiopian Biodiversity Insti-

tute has a large collection of over 10,000 sorghum accessions

from different regions of the country, a large portion of the

genetic diversity in this collection remains uncharacterized.

This study therefore aimed to characterize the extent and

patterns of the genetic diversity across different environ-

ments and to identify genome–environment associations in

Ethiopian sorghum germplasm.

Materials andmethods

Plant materials

A total of 940 diverse sorghum germplasm landraces were

used in this study (Online Resource 1). The genetic material

was obtained from the Ethiopian Biodiversity Institute and

the Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research’s Melkassa

Agriculture Research Center in 2015. The collections used

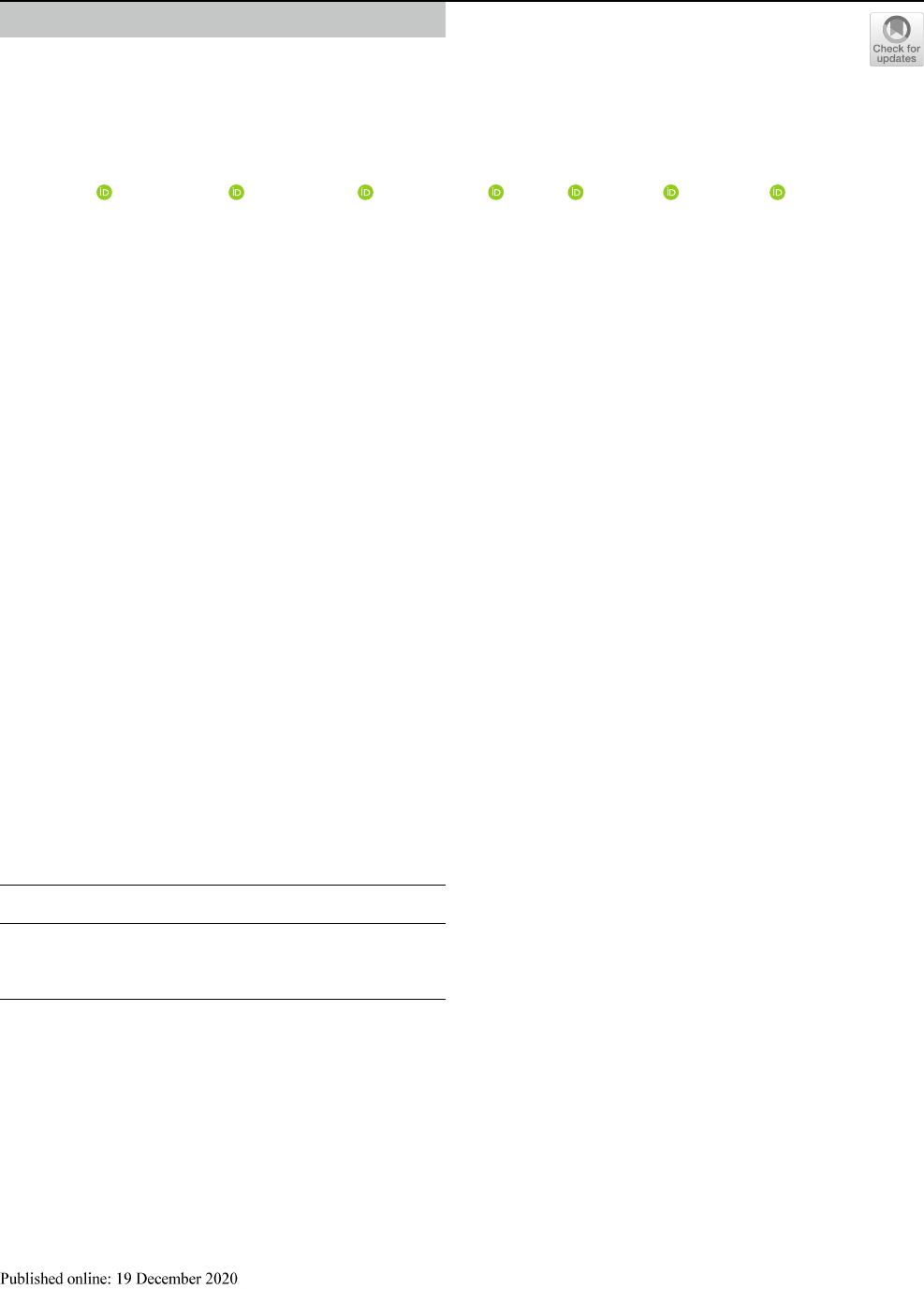

information on agroecologies (Fig.1a), altitudes (Fig.1b)

and sorghum production regions (Fig.1c) to systematically

select representative samples from all relevant regions of

the country (Fig.1d).

Total genomic DNA extraction andgenotyping

Leaf samples of four individual leaves were collected from

15-day-old plants grown in small pots in a greenhouse and

stored at −20°C in 96-well plates for 24h. The leaf sam-

ples were freeze-dried and sent to DArT (www.diver sitya

r rays .com) for DNA extraction. The DNA samples were

then genotyped using a genotyping-by-sequencing (GBS)

Fig. 1 Ethiopian geographical maps indicating a main agroecological

zones based on the Global 16 Class classification system by Amede

etal., (2015), b altitude, c sorghum production areas and d collection

sites of sorghum germplasm samples, with the size of the dots scaled

to indicate the number of samples selected at specific locations

Theoretical and Applied Genetics

1 3

whole-genome profiling method, DArTseq. This involves

complexity reduction of the genomic DNA to remove

repetitive sequences using methylation-sensitive restriction

enzymes prior to sequencing on next-generation sequencing

platforms. The sequence data generated were then aligned to

version v3.1.1 of the sorghum reference genome sequence

(McCormick etal. 2018) to identify SNPs (Single Nucleo-

tide Polymorphisms).

Data analysis

Pairwise linkage disequilibrium (LD) (r2) was calculated

using PopLDdecay (Zhang etal. 2019). The population

structure analysis was performed using LEA (Landscape

and Ecological Association Studies) version 1.8.1 in R

(Frichot and François 2015). The LEA package uses non-

negative matrix factorization (NMF) algorithms which are

based on sparse NMF and least-squares optimization (Fri-

chot etal. 2014) to estimate the subpopulation membership

or admixture for subpopulations. R package tess3r was used

to perform the spatial interpolation of ancestry coefficients

structure onto the Ethiopian geographical maps (Caye etal.

2016).

Redundancy analysis was performed using the varpart

function in R Vegan packages for independent variables of

agroecology and geographical locations. Agroecology vari-

ables were based on Amede etal. (2015) which estimated

agroecological zones in Ethiopia based on the Global 16

Class Classification System (Fig.1a). Accordingly, eight

Ethiopian agroecology zones have been identified: trop-

ics cool/humid, cool/subhumid, cool/semiarid, cool/arid,

warm/humid, warm/subhumid, warm/semiarid and warm/

arid. Sorghum also grown in all these agroecology except

col/arid and warm/humid. Ethiopia has two crop growing

season: Meher and Belg which receive rainfall from June

to October and February to June, respectively. Sorghum is

mainly grown in the Meher season, but farmers use the Belg

season’s rain (e.g., warm/semiarid regions) for late maturity

landraces to increase the duration of the growing period.

Geographical location variables were estimated from the

central point of latitude and longitude of each sample col-

lection, at the level of Woreda (District), depending on the

information available (Online Resource 1).

Principal component analysis (PCA) was undertaken

using DARWIN software version 6.0 (Perrier etal. 2003;

Perrier and Jacquemoud-Collet 2015) from dissimilarity

matrices. Dissimilarity indices (Modalities) were used to

generate dissimilarity matrices (Sokal and Rohlf 1962) for

PCA construction.

In order to identify the racial group classification of the

940 individuals, the SNP data generated in this study were

integrated with the global sorghum diversity panel SNP data,

where racial groups have been previously assigned (Tao

etal. 2020). Specifically, 10 individuals per subpopulation

were selected based on the matrix values of the individuals

in the group membership with coefficients greater than 0.85

and co-analyzed with 1033 individuals from the global sor-

ghum diversity panel. Botanical racial groups were assigned

using PCA (DARWIN, v6.0) based on 25,634 common SNP

markers between the Ethiopian landrace collection and the

global sorghum diversity panel.

Pairwise genome-wide nucleotide diversity (π) was cal-

culated using TASSEL 6 software (Buckler 2007) using the

Nei and Li (1979) model:

𝜋

=

∑

ij

x

i

x

j

𝜋

ij

, where

x

i

and

x

j

are

the respective frequencies of the ith and jth sequences, and

𝜋

ij

is the number of nucleotide differences per nucleotide site

between the ith and jth sequences.

Genome–environment association studies (GEA): three

environmental variables: altitude, annual temperature and

precipitation (averaged from 1960 to 1990), were used in

this study. The altitude variable used was based on the alti-

tude at the central point of the district, as identified in the

passport data. The annual temperature and precipitation

were extracted from 19 WorldClim derived bioclimatic vari-

ables using the R package raster (Hijmans etal. 2015) based

on the latitude and longitude coordinates for each of the geo-

referenced Ethiopian sorghum landraces. GEA was carried

out using Bayesian-information and Linkage-disequilibrium

Iteratively Nested Keyway in the R BLINK package (Huang

etal. 2018). The significance p value threshold was set based

on the Genetic Type I error calculator (GEC) of the P values

(Li etal. 2012) based on the effective numbers of independ-

ent tests.

A priori QTL on significant GEA SNP markers: A priori

previously identified candidate QTLs were identified that

colocated within 2cM of the significant GEA markers

(Mace etal. 2018), based on the LD decay pattern identified

in this study. Singular enrichment analysis was undertaken

using Chi-square with a P value ≤ 0.05 in R software with

the “chisq.test” procedure to identify whether the observed

GEA SNP markers colocating with previously identified

QTL were significantly different to the expected frequency,

based on the assumption of random distribution.

Results

SNP markers andlinkage disequilibrium (LD)

decay analyses

A total of 54,080 SNP markers were identified across the

940 landraces. Following exclusion of markers with > 25%

missing values, a subset of 50,367 SNPs was identified

and missing values inferred using the Beagle 5.0 software

Theoretical and Applied Genetics

1 3

package (Browning etal. 2018). The data set was further fil-

tered to exclude SNPs with MAF < 0.01, leaving a final data

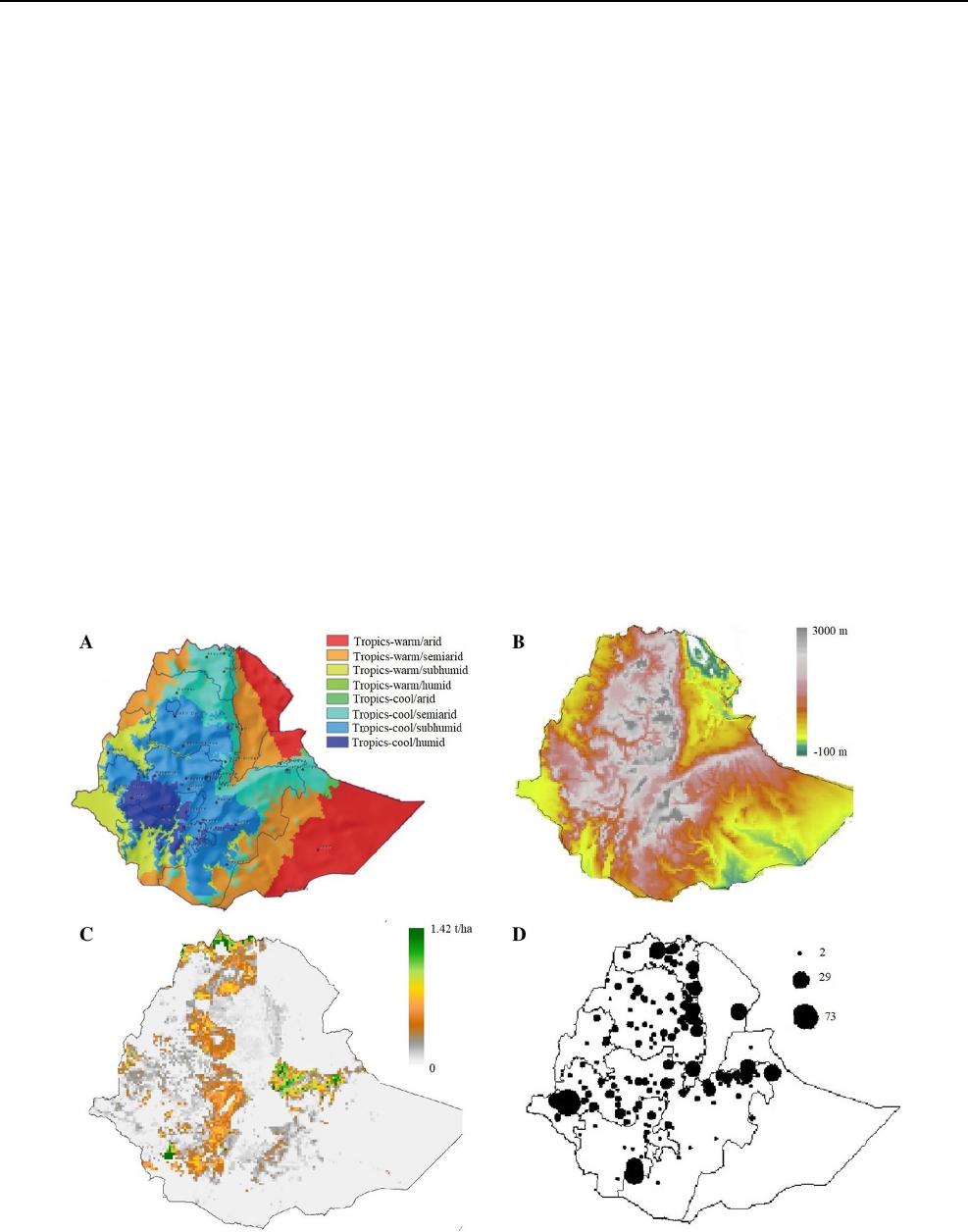

set of 25,634 robust SNP markers. Linkage disequilibrium

analysis identified that the LD decays to background levels

within 200kb (Fig.2) indicating a slower decay rate than the

global diversity panel described by Tao etal (2020).

Population structure

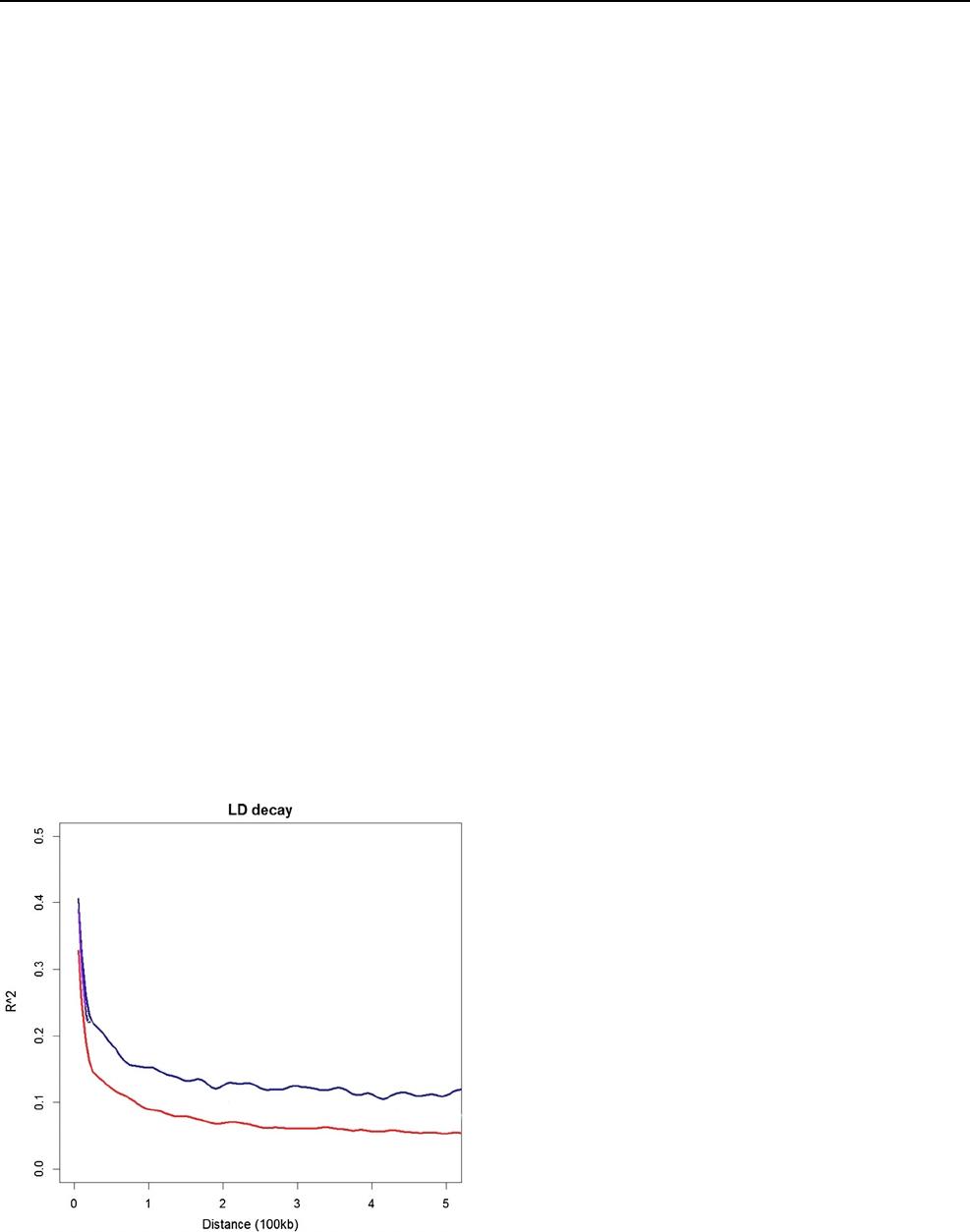

A population structure analysis of the 940 sorghum geno-

types for K ranging from 2 to 15 identified k = 12 as the

optimum number of subpopulations (groups) based on mini-

mizing the cross-entropy of the data (Online Resource 2;

Fig.3a). The LEA results largely supported the population

structure analysis with 53% of the genotypes being assigned

to one of the 12 subpopulations with a high than 0.60 ances-

try membership coefficient.

The spatial interpolation of ancestry coefficients, per-

formed using the tess3r package (Fig.3b), showed the max-

imal local contribution of geographical location in Ethio-

pia to ancestry, with individuals in specific subpopulations

found to colocate in geographic regions. For example, in

subpopulation G11 (dark green), the majority of the indi-

viduals with high membership coefficients were from the

western part of Ethiopia. Individuals containing high mem-

bership coefficients in subpopulations G7 (brown) and G10

(pale pink) were from Eastern Ethiopia; subpopulation G9

(dark blue) from Southern Ethiopia; subpopulation G4 (red)

from Northern Ethiopia; and subpopulations G2 (pink) and

G6 (orange) from Central Ethiopia. Due to the small sample

size and low ancestry coefficients within subpopulations G3

and G12, these two populations are represented as small dots

within G11 and G5, respectively, in Fig.3b.

The genetic variation and structure of the 12 subpopula-

tions of Ethiopian sorghum germplasm were also investi-

gated using a PCA plot. The first two principal components

(PCs) explained 22.5%–9.3% of the SNP variation, respec-

tively (Fig.3c). Subpopulations G2 (pink) and G6 (orange)

were clearly separated from other subpopulations based on

PC1. In contrast, subpopulation G8 (yellow) is distributed

throughout the PCA plot. The remainder of the populations

separated primarily on PC2.

Assigning botanical racial groups

The first two principal components explained 54.9% of

the SNP variation (Online Resource 3), and a selection

scheme used the PCA data to assign the botanical races to

the selected individuals from this study. Overall, the 940

Ethiopian landraces were enriched for durra types. Simi-

lar to the Ethiopian landrace-specific PCA plot (Fig.3c),

subpopulations G2 and G6 were clearly distinct from other

subpopulations, clustering with East African durra types

from the global sorghum diversity panel (Online Resource

4). The Ethiopian highland durra types from the global sor-

ghum diversity panel clustered with subpopulations G1, G4

and G5; the Asian durra types clustered with subpopulation

G10; the guinea botanical type with subpopulations G3, G9

and G12; the caudatum types clustered with subpopulation

G11; and finally the bicolor types with subpopulation G8.

A neighbor-joining tree was constructed for all 12 subpopu-

lations, based on an individual group membership coeffi-

cient > 0.60, using the R packages factoextra and hierfstat.

The genetic variation revealed by the neighbor-joining tree

analysis (Fig.3d) was in-line with the previous analyses and

in particular highlighted the divergence of subpopulations

G2 (durra types), G6 (durra types) and G8 (bicolor types)

from the other subpopulations (Online Resource 3).

Sorghum genetic andagroecology diversity

Genome-wide nucleotide variation was quantified across

landraces and subpopulations to investigate the genetic

diversification in Ethiopian sorghum. The overall SNP

genetic variation (π) per nucleotide was 0.12582 across all

940 Ethiopian sorghum germplasm. A total of 487 geno-

types were selected based on group membership coefficient

matrix > = 0.60 (60%) and geographical information used

to calculate the genetic diversity among the subpopulations.

The nucleotide diversity in SNPs within the subpopulations

ranged from 0.1637 to 0.0310 in subpopulations G8 and

G12, respectively (Table1). Individuals in subpopulations

G1, G4, G5, G7, G9, G10 and G12 were predominantly

Fig.2 LD (r

2

) Decay per Kb between pairs of loci across all chromo-

somes for the Ethiopian landraces (blue) and the sorghum diversity

panel (red) described in Tao etal (2020) (color figure online)

Theoretical and Applied Genetics

1 3

located in the cool semiarid agroecological zones. Individu-

als in subpopulations G2, G3 and G6 were largely located in

cool subhumid agroecological zones, whereas individuals in

subpopulations G8 and G11 were predominantly from warm

subhumid agroecological zones.

Similar to spatial interpolation of ancestry coefficients

(Fig.1b), individuals from subpopulations G2 and G6

(durra botanical races) were located across the majority

of the agroecological zones in Ethiopia; however, some

of the durra subpopulations had specific geographic dis-

tributions. For example, the G10 durra type was located

exclusively in the harsh (cool/semiarid) agroecology,

while the G6 durra type was located in the cool/humid

agroecology, and the G1 durra type was located in the

warm/arid agroecology. Guinea type subpopulations (G3,

G9 and G12) were located in most of the agroecologies of

the country, but primarily in the cool/subhumid followed

by cool/semiarid regions.

To better understand the variance contribution of agro-

ecology and geographical locations to genetic diversity,

sorghum landraces were sampled to include the majority of

the agroecologies, altitude zones and production areas relat-

ing to sorghum in Ethiopian districts. Redundancy analysis

was performed to estimate the proportion of SNP varia-

tion explained by agroecology and geographical locations

(Fig.4). This analysis indicated that 13% of SNP variation

was explained by agroecology and geographical location,

broken down as follows agroecology (7%), geographical

locations (3%) and agroecology collinear with geographi-

cal location (3%).

Fig. 3 Population structure in Ethiopian sorghum germplasm using

SNP markers. a Population structure for K = 12. Each vertical line

represents one genotype, and the color composition displays the prob-

ability of belonging to each of the 12 subpopulations. b Interpolated

values of admixture coefficients (K = 12) plotted geographically on

the map of Ethiopia. c A principal component analysis plot (vari-

ance explained by PC1 22.5% and PC2 9.3%). d Neighbor-joining

tree, indicating the genetic distance between the 12 subpopulations.

The color coding used in all plots can be clearly seen in A (G1: light

orange; G2: pink; G3: light green; G4: red; G5: bright blue; G6:

orange; G7: brown; G8: yellow; G9: dark blue; G10: pale pink; G11:

dark green; and G12: bright green)

Theoretical and Applied Genetics

1 3

Genome–environment association (GEA) studies

foradaptive traits

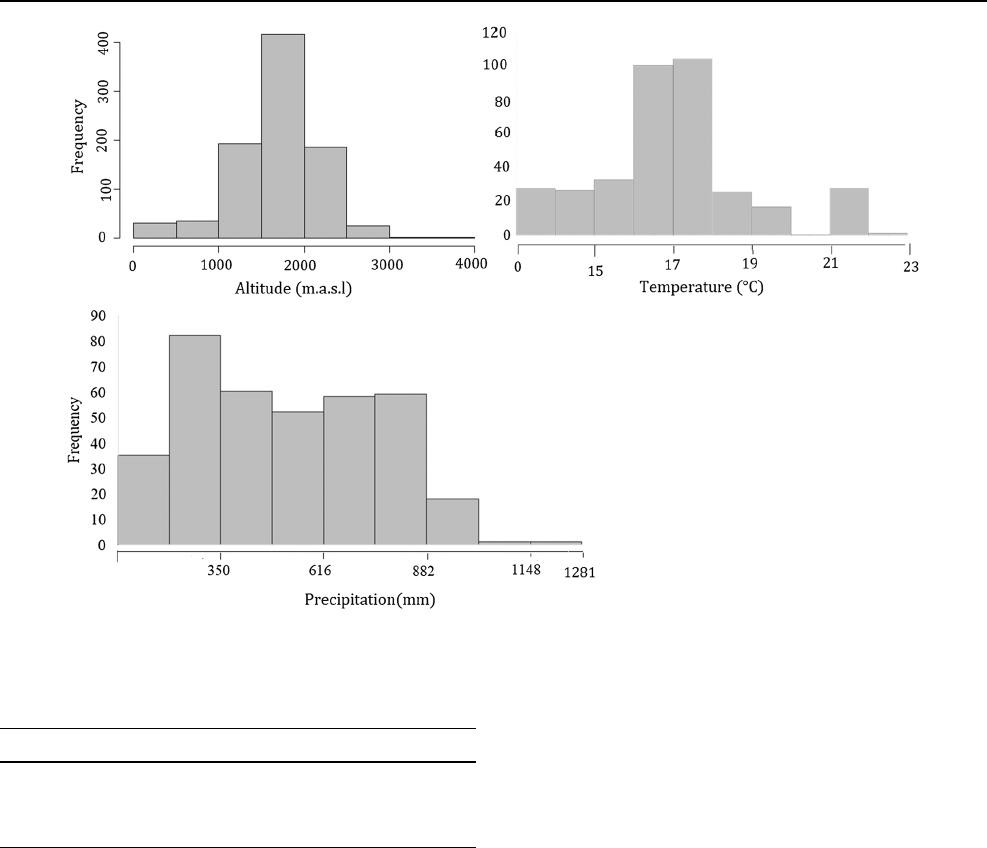

GEA was performed using selected bioclimatic data (alti-

tude, annual temperature and precipitation). The climatic

data, which were extracted from WorldClim‐derived bio-

climatic data (Hijmans etal. 2005), showed a normal dis-

tribution for altitude and temperature, but a skewed dis-

tribution for precipitation due to the inclusion of a small

number of individuals from high precipitation districts and

a large number of individuals from low precipitation dis-

tricts (Fig.5). This was a consequence of sorghum being

predominately grown in low rather than high precipitation

districts. The phenotypic correlations between the climatic

data indicated that temperature was highly negatively cor-

related with annual precipitation and altitude, while annual

precipitation was highly positively correlated with altitude

(Table2). To investigate genome and climatic association,

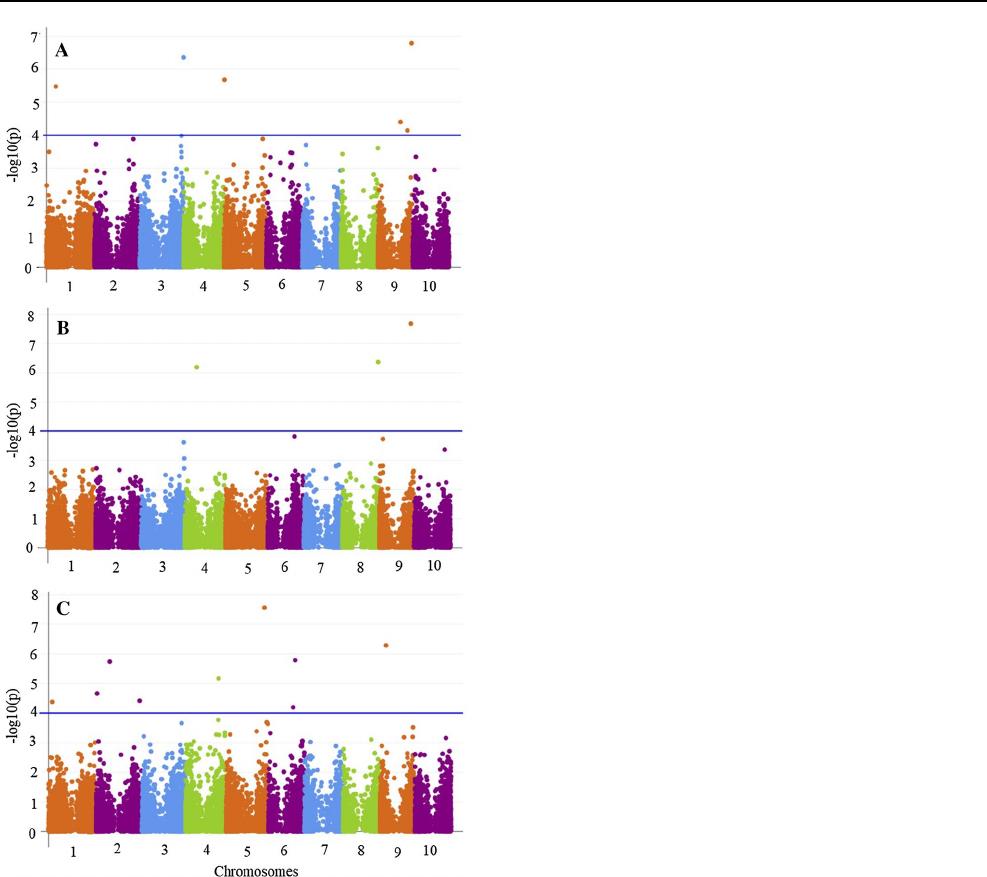

GEA analysis was conducted and identified a total of 18 sig-

nificantly associated SNP markers for altitude, annual mean

temperature and annual precipitation (Fig.6). Six significant

SNP markers were identified on chromosomes SBI-01, SBI-

03, SBI-05 (one SNP marker per chromosome) and SBI-09

(three SNP markers) for altitude (Online Resource 5). Three

significant SNP markers (one marker per chromosome) were

identified on chromosomes SBI-04, SBI-08 and SBI-09 for

annual mean temperature (Online Resource 5). Nine signifi-

cant SNP markers were identified on chromosomes SBI-01,

SBI-04, SBI-05, SBI-09 (one SNP marker per chromosome),

SBI-02 (three SNP markers) and SBI-06 (two SNP markers)

for annual precipitation. The percentage of the phenotypic

variance explained by each marker (R

2

) ranged from 0.5 to

3.2% (Online Resource 5).

A priori QTLs

The genomic locations of the GEA QTL identified were

compared with those of previously identified QTL for

drought and cold adaptation. Previous studies have iden-

tified 231 QTLs for drought adaptation (Online Resource

Table 1 Genetic diversity (botanical race and nucleotide diversity) and number of sorghum landraces assigned to main agroecology groups

among the 12 subpopulations

Gen. Genetic, π Nucleotide diversity, B. race Botanical race, Gr. Subpopulation

*Agroecology columns indicating the actual number and percentage of individuals in the specific subpopulations

Gr Gen. diversity Agroecology* Total /group

B. race π Cool/humid Cool/subhumid Cool/semiarid Warm/subhumid Warm/semiarid Warm/arid

G1 Durra 0.0680 0 (0.00%) 17 (29.31%) 27 (46.55%) 4 (6.90%) 3 (5.15%) 7 (12.07%) 58

G2 Durra 0.0676 3 (4.41%) 32 (47.06%) 29 (42.65%) 2 (2.94%) 1 (1.47%) 1 (1.47%) 68

G3 Guinea 0.0706 0 (0.00%) 15 (78.95%) 1 (5.26%) 3 (15.79%) 0 (0.00%) 0 (0.00%) 19

G4 Durra 0.0770 0 (0.00%) 25 (35.21%) 44 (61.97%) 1 (1.41%) 1 (1.41&) 0 (0.00%) 71

G5 Durra 0.0608 1 (1.89%) 5 (9.43%) 40 (75.47%) 1 (1.89%) 0 (0.00%) 6 (11.32%) 53

G6 Durra 0.0708 19 (22.89%) 34 (40.96%) 25 (30.12%) 2 (2.41%) 1 (1.20%) 2 (2.41%) 83

G7 Durra 0.0536 2 (4.65%) 2 (4.65%) 35 (81.40%) 1 (2.33%) 3 (6.98%) 0 (0.00%) 43

G8 Bicolor 0.1637 0 (0.00%) 2 (11.11%) 5 (27.78%) 10 (55.56%) 1 (5.56%) 0 (0.00%) 18

G9 Guinea 0.1030 0 (0.00%) 6 (35.29%) 10 (58.82%) 1 (5.88%) 0 (0.00%) 0 (0.00%) 17

G10 Durra 0.0530 0 (0.00%) 1 (5.00%) 18 (90.00%) 1 (5.00%) 0 (0.00%) 0 (0.00%) 20

G11 Caudatum 0.0736 1 (2.94%) 3 (8.82%) 3 (8.82%) 26 (76.47%) 0 (0.00%) 1 (2.94%) 34

G12 Guinea 0.0310 0 (0.00%) 0 (0.00%) 3 (100%) 0 (0.00%) 0 (0.00%) 0 (0.00%) 3

Total/

agroe-

cology

26 142 240 52 10 17 487

Fig. 4 SNP variance partitioning in Ethiopian sorghum explained

independently by agroecology and geographical locations (\AgE

agroecology, GL geographical locations)

Theoretical and Applied Genetics

1 3

6) and 636 QTLs for cold adaptation (Online Resource 7)

(Mace etal. 2018).

A total of eight significant precipitation SNP mark-

ers were colocated within a 2cM flanking region of 19

previously identified drought adaptation QTL (Online

Resource 8), with a significant genome-wide enrichment

(P = 0.02675). For cold tolerance, a high confidence subset

of the total number of QTL previously identified with a

confidence interval of < 10cM were used for the genetic

enrichment analysis. Out of six significant temperature-

associated SNP markers, three were colocated with 18 pre-

viously studied cold adaptation QTL (Online Resource 8),

again representing a significant genome-wide enrichment

(P = 0.0231). Out of six significant SNP markers for alti-

tude, five were significantly colocated with 25 previously

identified cold adaptation QTL (P = 6.831e

−06

) (Online

Resource 8).

Discussion

Information on genetic diversity is required for conservation

and utilization of genetic resources. Currently, only a small

portion of the genetic diversity of the Ethiopian sorghum

collection is characterized, and therefore useful, for sorghum

breeding programs. Through the integration of information

from sorghum production regions with genome-wide SNP

data, it is possible to investigate the genomic basis for cli-

mate adaptation. This study focused on the extent and pat-

tern of genetic diversity, including genome environmental

associations, of a large collection of Ethiopian sorghum

landraces.

The large panel of Ethiopian sorghum landraces, repre-

sentative of all of the key agro-climatic zones in Ethiopia,

was characterized with medium density SNP markers and

found to cluster into 12 subpopulations with high admix-

ture (47%). The high admixture observed is likely due to

gene flow among subpopulations, where close geographic

proximity, resettlements of different population groups

within the country, seed trading and the common practice

of farmers growing multiple landraces in the same field

would have contributed to increasing gene flow (Desmae

Fig. 5 Frequency of individual sorghum landrace for climatic variables. M.a.s.l = meter above sea level

Table 2 Correlation among the climatic variables

Astrisk indicates that number and percentage of individuals per sub-

population in the Table; number outside the bracket is actual number

individuals and in bracket is individual coverage percentage per sub-

population or per column

Altitude Temperature Rainfall

Altitude 1.0

Temperature −0.64** 1.0

Precipitation 0.66** −0.62** 1.0

Theoretical and Applied Genetics

1 3

etal. 2016). Recent studies on Ethiopian sorghum germ-

plasm also reported significant differentiation within the

collections, with high numbers of population clusters

identified (K = 11), and comparable amounts of admix-

ture (35%) in the Ethiopian collection (Girma etal. 2019)

and 47% admixture in the USA National Plant Germplasm

System (Cuevas etal. 2017) identified.

A large proportion ofvariance

wasnotexplained byeitheragroecology

orgeographical location

Many studies have indicated that sorghum diversity is

linked to either geography, agroecology and/or botani-

cal racial classifications (e.g., Barnaud etal. 2007; Lasky

etal. 2015; Faye etal. 2019). In this study, a low propor-

tion of variation was explained by agroecology and geo-

graphical location (Fig.4), with agroecology explaining

more than geographical location. This suggests that agro-

ecology is more important than geographical location in

shaping variation for sorghum clinal adaptation. A large

proportion of variance was not explained by either agro-

ecology or geographical location, suggesting that other

factors such as human activities or human settlement could

be significant. For instance, Smith and Frederiksen (2000)

stated that the main growers of durra sorghum in Ethiopia

were Muslim Oromo who settled in the fertile warm high-

lands and have used the botanical race of durra sorghum

as the foundation of their agricultural system. Globally,

the durra-type sorghum is predominantly grown in warm

semiarid or warm desert climates (Morris etal. 2013), but

in Ethiopia, it grows in most of the agroecological zones,

including the cool humid zone (Table1). This indicates

that the most likely contribution of human activities for

sorghum adaptation is human settlement and seed shar-

ing by farmers. Recent studies also reported that genetic

structure in sorghum has been shaped by seed sharing

and based on ethnolinguistic grouping (e.g., Ng’uni etal.

2011; Olatoye etal. 2018; Faye etal. 2019; Labeyrie etal.

2014, 2016) and historical processes of domestication and

diffusion (Morris etal. 2013).

Ethiopian sorghum diversity isdominated

bythedurra race

Most of the sorghum subpopulations identified in this

study (G1, G2, G4, G5, G6, G7 and G10) belong to the

durra botanical race, indicating that most of the sorghum

collections in Ethiopia are dominated by durra. This result

agrees with other studies that reported the durra botani-

cal race was the most frequently found race in Ethiopia

(Harlan and Stemler 1976; Smith and Frederiksen 2000;

Morris etal. 2013; Cuevas etal. 2017), as their domestica-

tion is associated with the Ethiopian region. However, as

the results of this study have indicated, Ethiopia does have

genetic resources of the other three races (guinea, cauda-

tum and bicolor), and this has also been noted previously

(De Wet etal. 1976; Harlan and Stemler 1976; Reddy etal.

Fig. 6 GEA across the Ethiopian sorghum landrace collection using

25,716 SNP markers (MFA ≥ 0.01). Manhattan plots showing signifi-

cant false discovery rate (FDR) adjusted P value of < 0.05 associated

with climatic variables for (A) altitude, (B) annual temperature and

(C) annual precipitation. The x-axis represents the chromosomes and

the y-axis the –log10 (P values) for marker–trait association. Each

point represents the SNP marker. The threshold is set based on the

Genetic Type I error calculator (GEC) of the P values

Theoretical and Applied Genetics

1 3

2002). In the current study, the kafir botanical race was not

identified in the germplasm studied. This might be due to

the low frequency of this botanical race in the Ethiopian

sorghum collection, but an earlier report also indicated

that only four of the main five botanical races of sorghum

(with kafir being the exception) were grown in Ethiopia

(Engels etal. 1991). However, in the sorghum germplasm

collected from Ethiopia by ICRISAT, although also domi-

nated by the durra race (~ 43%), a small number of kafir

racial types (~ 0.1%) were identified (Reddy etal. 2002).

This population isanexcellent resource forbreeders

trying toidentify sources ofadaptation

Understanding how sorghum botanical race divergence is

related to agroecological zones enables (a) breeders to nar-

row down their search to meet breeding objectives and (b)

germplasm collectors to target specific agroecological areas

for specific botanical types. Today, it has been estimated that

as much as 20% of exotic sorghum lines adapted to temperate

regions have originated from Ethiopia, indicating the value

of these genetic resources (Zhang etal. 2015). In the current

study, the durra subpopulations G2 and G6 were distributed

throughout most of the Ethiopian geographical locations and

agroecologies, indicating adaptation to a wide range of dif-

ferent Ethiopian environments (hot/dry and cold/wet), and

indicating that the durra botanical race has the ability to

grow in extreme agroecologies. The durra types therefore

offer a valuable reservoir of important new adaptive alleles

to both temperature and water stresses, advancing the use of

this germplasm collection. This has also been reported previ-

ously; for example, Singh (1985) reported that the highest

levels of cold adaptation globally have been found among

accessions from Ethiopia, compared with germplasm col-

lections from China and Uganda.

The guinea botanical racial types identified in this study

were distributed mainly in cool subhumid areas and, to a

lesser extent, cool semiarid areas (Table1). This contradicts

the expectation that the open-panicle architecture exhibited

by guinea types may be better adapted to humid regions

(Morris etal. 2013). In fact, the cool subhumid and cool

semiarid regions in Ethiopia are 1200m above sea level

and are considered as mid-altitude with a growing season

of > 70days at a time when both moisture and temperature

are conducive to crop growth (HarvestChoice 2010) and high

rainfall, reflecting conditions which are more suitable for

open-panicle types. In addition, soils in most of these high-

and mid-altitude regions are very acidic due to high rainfall

(Regassa and Agegnehu 2011), and the guinea botanical race

has previously been reported to have increased tolerance to

Al toxicity compared to other races (Caniato etal. 2011).

This characteristic is one of the main breeding targets in acid

soil regions, and hence, the guinea racial types identified

here offer a valuable source of adaptive alleles for breeding

programs (Garvin and Carver 2003).

GEA was performed using altitude, annual temperature

and precipitation to further identify the genomic regions

underlying local climatic adaptation traits in Ethiopian sor-

ghum germplasm. Tirfessa etal. (2020) reported that the

base temperature (Tbase, a minimum temperature required

for germination) in Ethiopian sorghum genotypes varies

from 0°C –9.8°C which is significantly different from that

of Indian and Australian germplasm (Tbase = 11°C). Such

variation in base temperature may provide a basis for selec-

tion adaptation to either low- or high-temperature environ-

ments (Mann etal. 1985).

In the current GEA study, a total of 18 significantly asso-

ciated SNPs were identified for altitude (6), annual mean

temperature (3) and annual precipitation (9) and were colo-

cated with 74 previously studied drought and cold adapted

QTLs (19 for precipitation with drought, 18 for temperature

with cold, 25 for altitude with drought and 12 for altitude

with cold; Online Resource (8)). Eight precipitation QTLs

for drought tolerance and three temperature QTLs for cold

tolerance showed a significant genome enrichment, indi-

cating the observed frequency of GEA (precipitation and

temperature) was significantly different from the frequency

expected by chance for drought and cold adaptation.

Conclusion

Using sorghum germplasm from the Ethiopian Biodiversity

Institute, a diverse collection of Ethiopian sorghum lan-

draces was characterized and found to comprise 12 subpopu-

lations that were largely dominated by the durra botanical

race, with no representation of the kafir botanical race. The

study also identified that up to 10% of the genomic variance

was explained by agroecology, with geographic location

explaining up to 6%, indicating that other factors are also

important for sorghum genetic variation in Ethiopia, includ-

ing human settlement and seed exchange among farmers.

Genome–environment association and candidate regions

for significant SNP markers indicated that local adaptation

to climatic variables has played an important role in sor-

ghum variation. This study confirmed that diverse Ethiopian

sorghum germplasm has adaptive alleles which could be a

source of useful genes for environmental stress adaptation.

Validation and prioritization of the genes found around the

significant QTLs in this study should be carried out via

genetic and molecular analyses.

Acknowledgements We thank the Ethiopian Biodiversity Institute

(EBI) and EIAR’s Melkassa Agricultural Research Center for provid-

ing us with the sorghum landraces and passport data. This study was

supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation PEARL (Program

for Emerging Agricultural Leaders) Program.