Contribution of agroforestry trees for climate change

adaptation: narratives from smallholder farmers in Isiolo,

Kenya

Amy Quandt

Received: 7 April 2020 / Accepted: 4 September 2020

Ó Springer Nature B.V. 2020

Abstract Agroforestry is often praised as a sustain-

able approach for the adaptation of smallholder

farmers to climate change and variability in Africa.

The environmental, economic, and social benefits of

agroforestry can contribute to climate change adapta-

tion efforts; however, most studies to date are

quantitative and do not focus on specific natural

hazards. To address these gaps, this study draws from

the concepts of vulnerability and adaptation to explore

how individuals from 20 smallholder farming house-

holds in semi-arid Isiolo County, Kenya have bene-

fited from their agroforestry trees during drought and

flood events. A total of 83 qualitative interviews were

conducted with both male and female household

heads. The interviews were recorded, and interview

text was coded into major themes. The results

highlight (1) the contributions of agroforestry trees

to reducing sensitivity and increasing adaptive capac-

ity to drought and flood events, as well as (2) the key

characteristics of drought-important and flood-impor-

tant agroforestry trees. In both drought and flood

events agroforestry had an important role to play in

reducing sensitivity, largely through improving envi-

ronmental conditions (shade, soil erosion, wind-

breaker, micro climate regulation), and increasing

adaptive capacity by providing critical tree products

and financial benefits (fruit, food, firewood, construc-

tion materials, fodder, traditional medicines, money

from sales of fruit products). Agriculture is often

considered the livelihood strategy most vulnerable to

climate change, and thus better understanding how to

adapt agriculture to the impacts of climate change is

critical for both the livelihoods of smallholder farmers

and global food security efforts.

Keywords Adaptation Agroforestry Climate

change Kenya Sensitivity Vulnerability

Introduction

Agroforestry is often praised as a sustainable approach

for the adaptation of smallholder farmers to climate

change and variability in Africa, as well as Kenya

more specifically (Quandt et al. 2017; Bisong and

Larwanou 2019; Amadu et al. 2020). Agroforestry can

contribute to adapting smallholder agricultural sys-

tems to the impacts of climate change by creating

microclimates with lower mean air temperatures and

higher soil moisture (Gomes et al. 2020); reducing

crop transpiration rates by shading crops (Verchot

et al. 2007; Lin 2010); drawing water from deeper soil

layers and supporting root water update by crops

(Padovan et al. 2015); minimizing soil loss from water

erosion during flooding (Lal et al. 1991); enhancing

A. Quandt (&)

Department of Geography, San Diego State University,

5500 Campanile Drive, San Diego, CA 92182-4493, USA

e-mail: [email protected]

123

Agroforest Syst

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10457-020-00535-0

(0123456789().,-volV)(0123456789().,-volV)

soil fertility (Awazi and Tchamba 2019); diversifying

production systems and producing crops of high

economic value (Verchot et al. 2007); contributing

to financial capital (Quandt et al. 2018); and building a

household’s livelihood resilience (Quandt et al. 2017).

However, more research is needed to holistically

understand agrofore stry as a tool that sma llholder

farmers can use for effective, sustainable, and cost-

efficient adaptation to the impacts of climate change

(Verchot et al. 2007; Awazi and Tchamba 2019).

Importantly, most studies to-date focus on the

general benefits of agroforestry trees to livelihoods,

without focusing on the adaptation potential of

agroforestry to a specific climate change-impact, such

as a drought (Reppin et al. 2020). Further, most recent

social science-focused research has relied on large-

scale surveys and qu antitative analysis, while there

remains a lack qualitative work (for examples, see

Awazi and Tchamba 2019; Awazi et al. 2019;De

Giusti et al. 2019; Nyong et al. 2019; Paudel et al.

2019; Tran and Brown 2019; Reppin et al. 2020). To

fill these research gaps, this paper takes a qualitative

approach because adaptation to climat e change often

occurs at the local level, where climatic variability is

directly experienced by individuals (Olufemi et al.

2018). Qualitative research is an effective tool for

understanding meaning, interpretations, and individ-

ual experiences by analyzing stories, narratives, and

lived-experiences (Bernard 2011; Overland and Sova-

cool 2020). Thus, this research draws from the

concepts of vulnerability and adaptat ion to explore

how individuals from 20 smallholder farming house-

holds in Isiolo County, Kenya have benefited from

their agroforestry trees during drought and flood

events. Specifically, this paper highlights the research

participants’ perspectives on (1) the contributions of

agroforestry trees to reducing sensitivity and increas-

ing adaptive capacity to drought and flood events, as

well as (2) the key characteristics of drought-impor-

tant and flood-important agroforestry trees.

Vulnerability and adaptation

In the context of climate change, vulnerability can be

defined as the degree to which a system is susceptible

to, or unable to cope with, adverse effects of climate

change, including climate variability and extremes

(Adger 2006; IPCC 2014; Olufemi et al. 2018). The

key components of vulnerability are often explained in

the following formula (IPCC 2014; Olufemi et al.

2018):

Vulnerability ¼ exposure þ sensitivity

ðÞ

adaptive capacity:

Exposure is the degree to which a system experi-

ences stress, including the magnitude, frequency,

duration, and area extent of the stress; for example

the frequency and intensity of a flood event (Adger

2006; Olufe mi et al. 2018). Sensitivity is the degree to

which a system is modified or affected by perturba-

tions (Adger 2006). Thus, increased exposure and

sensitivity to a drought or flood event would increase

vulnerability. Importantly, livelihood activities and

human behavior, such as practicing agroforestry, can

influence (improve or decrease) a systems’ sensitivity

to exposures (Smit and Wandal 2006).

Significant to this research are the concepts of

adaptation and adaptive capacity. Adaptation in the

context of climate change usually refers to a process,

action, or outcome in a system in order for the system

to better cope with, manage, or adjust to some

changing condition, stress, hazard, risk, or opportunity

(Smit and Wandal 2006). The adaptive capacity of a

system refers to its ability to adjust to potential

damage, take advantage of opportunities, or to respond

to consequences (IPCC 2014). Adaptations are man-

ifestations of adaptive capacity, and they represent

ways of reducing the vulnerability of households and

individuals to climatic change and variability (Smit

and Wandal 2006; Adger 2006). There is a critical

need to develop adaptation options to reduce the

vulnerabilities induced by climate change (Wheaton

and Maciver 1999), and thus this research draws on the

concepts of vulnerability and adaptation to understand

how agroforestry can be an effective adaptation

strategy to reducing smallholder farmer vulnerability

to drought and flood events.

Methods

The methods section below describes the study area,

data collection and analysis methods, and outlines the

limitations of the researc h methods. The study design

took a cross-sectional, qualitative approach and drew

from interviews in two communities in Isiolo County,

Kenya.

123

Agroforest Syst

Study area

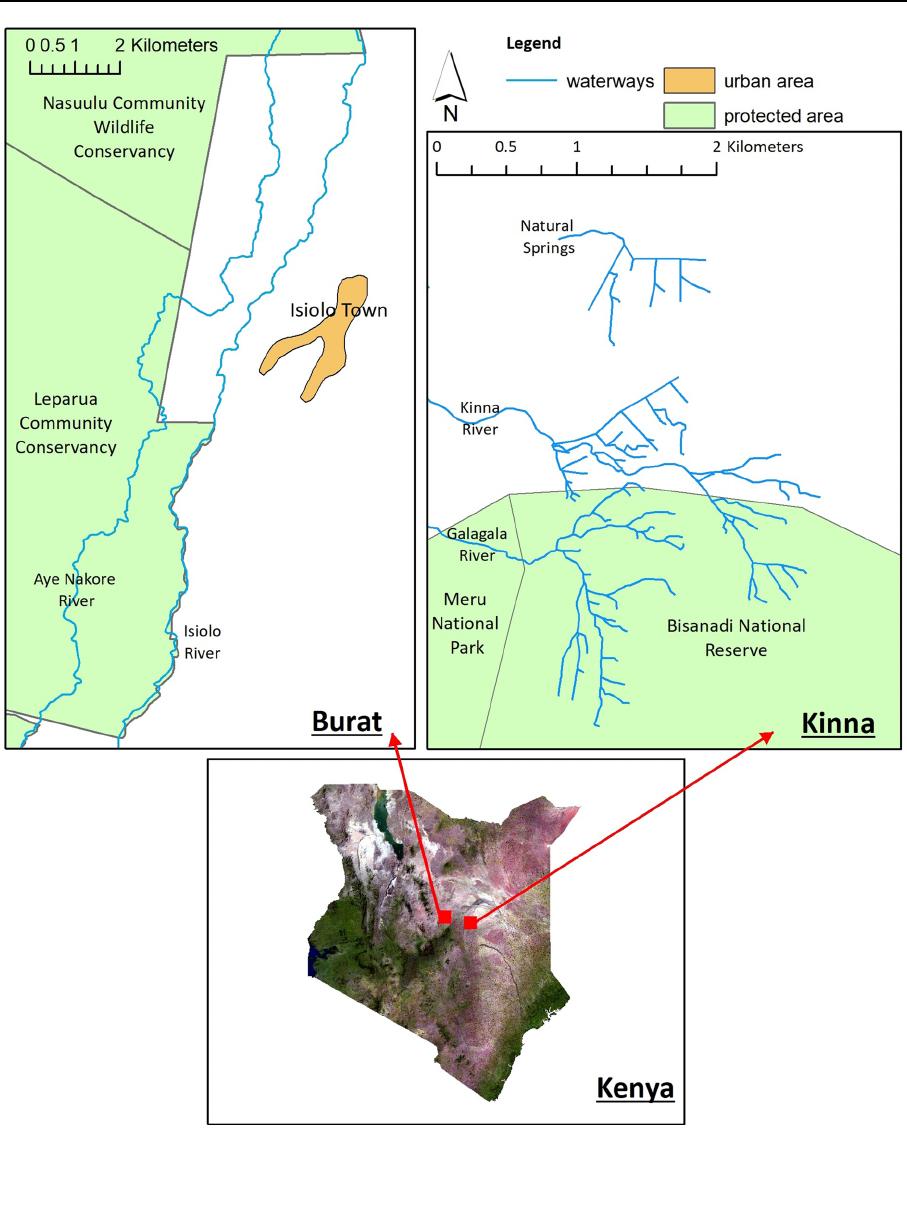

This research took place in the communities of Burat

and Kinna in Isiolo County, Kenya (Fig. 1). This study

area was chosen because (1) there is little agroforestry

research from semi-arid regions (2) Burat and Kinna

are the major agricultural areas of Isiolo County, and

(3) there have been no recent agroforestry projects in

these communities, and thus interview respondent’s

answers were not influenced by such projects. Burat

and Kinna fall into the only 5% of Isiolo County that is

classified as semi-arid (the remainder is arid or very

arid), with median annual rainfall ranging from 400 to

600 mm (Mati et al. 2005). At the time of data

collection (2014–2015) most farmers had no official

title to their land, although the process of land titling

was beginning in Burat towards the end of 2015.

Further, it is important to note that neither community

has taken part in any major agroforestry projects, and

that agroforestry adoption has instead happened

without any influence of an official project or inter-

vention. Instead, agroforestry adoption often took

place through interethnic exchanges, including busi-

ness and social interactions, between Meru farmers

and the other, predominately traditionally pastoralist,

ethnic groups.

Burat is located outside of Isiolo Town, and is

ethnically diverse, including Turkana, Meru, Somali,

Borana, and Samburu ethnic groups. Agriculture

began in Burat during the colonial period on small-

scale farms run by British government officials,

however agriculture began in earnest 40 years ago

when Meru from neighboring areas moved onto the

land (personal communication). Presently, irrigation

in Burat is through a system of pipes and generators

from the Isiolo and Aye Nakore rivers. Some of this

infrastructure is privately owned, and some was

constructed by aid organizations. Tree planting began

in Burat in the early 1970s, but agroforestry wasn’t

seriously adopted until the early 1980s (per sonal

communication).

Kinna is a 2 hour drive from Isiolo Town, and

60 km from Garbatulla town. Kinna is dominated by

the Borana ethnic group, with some Meru present.

According to Kinna elders, the Kinna irrigation

scheme (a system of canals fed by one spring and

two small rivers) was dug by the Kenyan National

Government in 1969 and land was allocated on a first

come basis (personal communication). Adopting

agriculture was a strategy for livestock poor Borana

in the decade after independence, when many live-

stock were lost from drought, disease, and negative

government policies (Otuoma et al. 2009).

Drought and flood are two climate change-impacts

that can and do occur in Isiolo County. It is important

to talk about the exposure of these communities to

droughts and flood as exposure is a key component of

vulnerability. According to Funk et al. (2010), since

the 1970s the long rains have declined by more than

100 mm and there has been a warming of more than

1 °C. Water scarcity and recurrent drought are major

constraints to agricultural developm ent in Isiolo

County (Mati et al. 2005) and this is reflected in

previous research in Isiolo County. Quandt (2017),

found that household survey respondents reported

major drought events in 2014, 2011, 2009, and 1984,

and reported a major flood event during the 1997 El

Nin

˜

o. Also, Quandt et al. (2017) found that in Burat

and Kinna 51% of survey respondents reported that

drought was more frequent than 10 years ago, and the

timing of the rains was less predictable (88%). In a

study of 7 communities throughout Isiolo County,

survey respondents reported that drought seriously

impacts agriculture (39% of respondents) and live-

stock keeping (44%), while flo ods impact agriculture

(71%) and livestock keeping (17%) (Quandt and

Kimathi 2017). Agroforestry in Burat and Kinna is

largely dominated by fruit trees, and the major tree

species planted, in order, were papaya, mango, guava,

banana, and neem (Quandt et al. 2018).

Data collection

A total of 20 households, 7 in Kinna and 13 in Burat,

took part in a series of qualitative interviews. At each

household the aim was to interview both the male and

female head of household in order to capture the

experiences of both male and female smallholder

farmers with agroforestry as a tool for climate change

adaptation, which may be different as has been

previously documented (Quandt 2019). However, this

was sometimes not possible when a household only

had a single household head or when one of the

household heads spent significant time away from

home. Each household took part in three rounds of

interviews including an initial interview (Sept 2014),

an interview during the dry season (Oct 2014), and

during the rainy season (Dec 2014). There were a total

123

Agroforest Syst

Fig. 1 Study area map

123

Agroforest Syst

of 83 interviews conducted with individuals from

these 20 households. The number of respondents

varied for each round of interviews based on who was

home and available at the time. Households were

selected based on combined convenience and respon-

dent-driven sampling (Bernard 2011). All interviews

were conducted in Swahili by myself, of which I am

fluent. Further, all interviews were conducted in

private, with no other household members or neigh-

bors sitting in on the interviews. A local research

assistant helped to locate the households and to

understand some of the more context-specific answers

(places, people, events, etc.). All interviews were

voice reco rded and later transcribed verbatim in

Swahili. In order to maintain the anonymity and

confidentiality of the research participants, in the

results section individuals are identified by a letter (B

for Burat, K for Kinna), a randomly assigned number

given to each household, and a letter identifying their

gender (F for female, M for male).

The goal of the initial interview, which was semi-

structured, was to build trust between myself and the

research participants and understand the household

characteristics and livelihood activities. The dry and

rainy season interviews were in-depth, unstructur ed

interviews that focused on 6–8 topics of disc ussion.

The discussion during the dry season interview

focused on drough t, while the rainy season interview

focused on floods. The aim of all the interviews was to

understand the interviewees ‘lived experiences’ with

agroforestry during drought and flood events, and

there is evidence that 10–20 knowledgeable people are

enough to accomplish this goal (Bernard 2011).

Data analysis

Analysis of the transcribed interview text was com-

pleted with assistance from QSR Nvivo 10 software.

The three-step coding process was completed with the

text in Swahili to maintain the original themes. First,

all the interview transcriptions were thoroughly read

and quotes placed into different thematic codes.

Thematic coding used both a priori codes , themes

that I expected to emerge as a result of the research

topic and questions, and a posteriori codes, or themes

that emerged from the interviews that were not

foreseen (Cope 2005). Second, after the initial coding,

I read through all the quotes in each code and

reorganized where necessary to ensure that all quotes

were placed under the correct thematic code. Last ly, I

reread all the interviews to ensure that all interview

text that could be classified within a thematic code was

properly coded. This three step process helped to

ensure that the final thematic codes were as thorough

and accurate as possible.

Limitations of research methods

There are three major limitations of this study design.

First, the findings are based on the interviewees’

general experiences with agroforestry during drought

and flood events. I did not focus on any specific

drought or flood event, and while sometimes the

discussion ended up focusing on a particular event, the

study was meant to speak about drought and floods

more generally. Second, the data represent only a

snapshot of the research participants’ lives and

livelihoods. A longer, longitudinal study would per-

haps capture more nuance about how people are

adapting to droughts and floods. Lastly, because the

research included multiple interviews, a handful of

individuals who participated in one or more interviews

were dropped from the research study and their

responses are not presented here. The major reasons

for dropping these households/individuals were that

(1) the interv iewee themselves refused to be inter-

viewed during the second or third interviews, (2) the

truthfulness of their responses was questionable, and/

or (3) they relocated over the course of the study.

During the initial interview, 16 households in Burat

and 11 households in Kinna were selected. However, a

total of 13 households in Burat and 7 in Kinna

participated in all three rounds of interviews.

Results

The results below highlight the contributions of

agroforestry to reducing the vulnerability of intervie-

wees during flood and drought events by both reducing

their sensitivity to these events, while also increasing

their adaptive capacity. As drought is the prominent

natural hazard facing households in Burat and Kinna,

drought was much more commonly discussed by

interviewees than floods.

123

Agroforest Syst

Drought

Contributions of agroforestry trees to reducing

sensitivity and increasing adaptive capacity

to drought

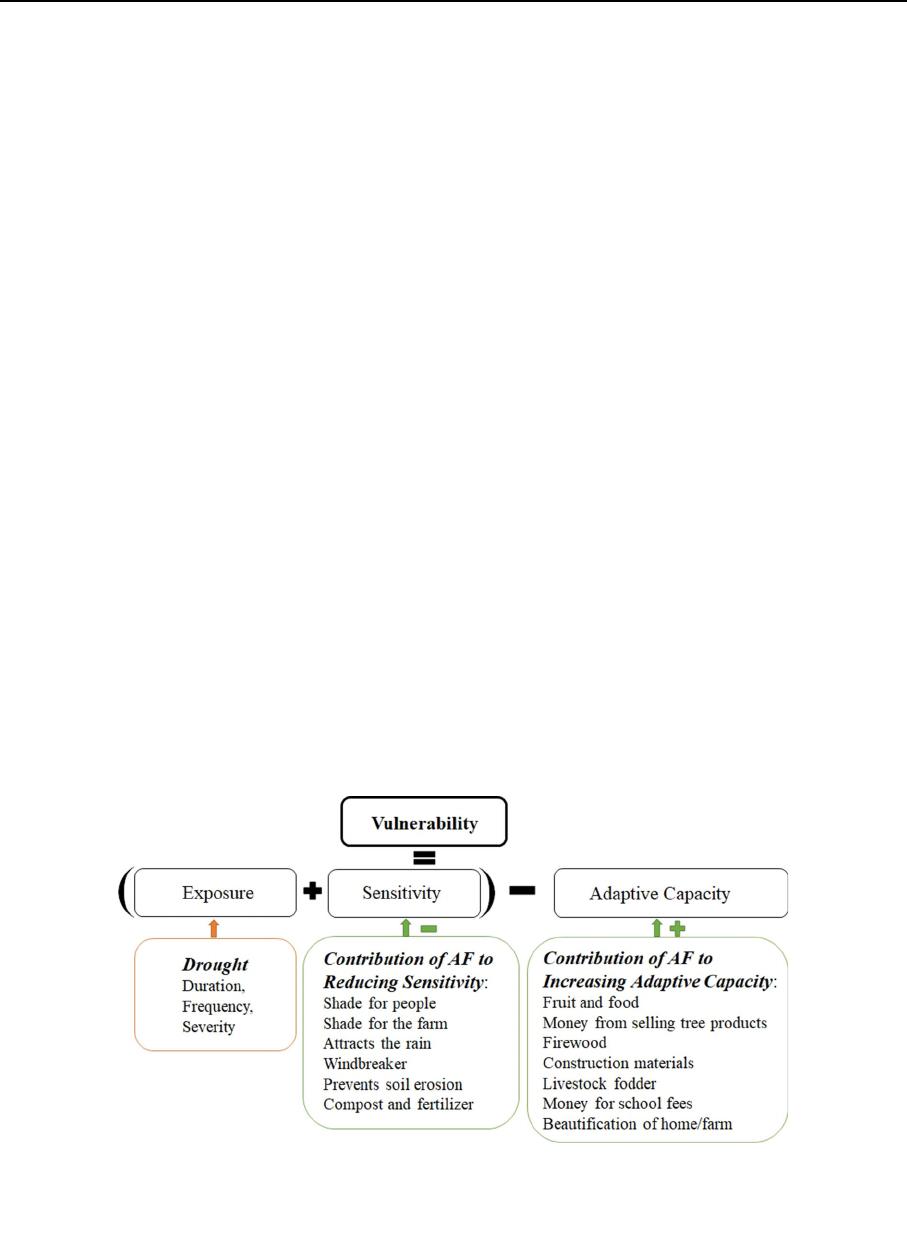

Interviewees discussed a wide variety of benefits that

they receive from their agroforestry trees during

drought. In Fig. 2, these benefits have been organized

into the contributions of agroforestry that help reduce

an individual’s or household’s sensitivity to drought,

and those that increase their adapt ive capacity before

or during a drought. The sensitivity category is

dominated by the environm ental benefits of agro-

forestry trees, and many interviewees highlighted the

importance of shade during drought, both for people

and their farms. For example, in discussing trees on his

farm, a male farmer in Kinna (K10M) stated that,

Now during a bad drought I think that if a person

rests in the shade here or in another place it is

different. Like right now, for other people it is

hot, but for us resting here it is cool because of

the tree’s shade. So now, we do not feel the heat

very badly. If I go somewhere else to work, I will

come home and fall down right here under this

tree until my body cools down.

Two other commonly discussed environmental bene-

fits were preventing soil erosion and acting as a wind

breaker. During the dry season many places in the

study communities become dry, windy, and dusty, and

decreasing these impacts helps reduce sensitivity to

these impacts of drought. For example, a female

farmer in Burat (B11F) stated that her trees ‘‘Prevent

soil erosion,’’ and a male farmer in Burat (B12M)

discussed how ‘‘In an area where someone has planted

trees like I have here, if the wind blows it will be

pushed up. And if you go to visit someone who has not

planted trees, you see that the wind comes directly at

you strongly.’’

The contributions of agroforestry trees to increas-

ing an interviewee’s adaptive capacity to drought

included the provisioning of household necessities like

food, firewood, livestock fodder, and construction

materials. For example, a male farmer in Burat (B5M)

stated that ‘‘These trees I planted because, like, this

fruit I knew that this fruit I would eat. Okay, these trees

are also lumber, I know that they would become

lumber, also I knew that they were good for cattle to

eat during drought.’’ A female farmer in Burat (B4F)

emphasized the importance of fruit for improving her

household’s food security during drought when she

stated that ‘‘The times when we do not have any food,

we can get it from these trees. This is a really big

benefit of these trees.’’

Importantly, interviewees discussed the importance

of the financial benefits from selling tree products. For

example, a female farmer in Burat (B13F) stated that,

Fig. 2 Contributions of agroforestry trees to reducing sensitiv-

ity and increasing adaptive capacity to drought. The contribu-

tions are organized into benefits that reduce an interviewee’s

sensitivity to drought, and those that increase their adaptive

capacity. The benefits included here are all the different benefits

that were discussed during the qualitative interviews. All related

themes or codes have been included

123

Agroforest Syst

‘‘ I get my income from fruit. Like now, my husband

does not bring home much money, it is very little. Now

this, now our papaya if I sell some fruit on Saturday,

500 shillings, I take out 300 for food, and this 200 if it

is left I save it. It helps us to pay for nursery school fees

for this child, or if there are any needs for my older

daughter.’’ Another female farmer in Burat (B16F)

echoed these sentiments and discussed that ‘‘Like

these mangos, I sell them to people, and I can

sometimes make enough money for two weeks of food.

Here there is no drought like there is in other places,

they [trees] help me.’’

Characteristics of drought-important trees

To better understand how agroforestry can be an

effective adaptation strategy to drought, interviewees

were also asked to discuss what specific characteristics

of trees are important for a tree to be beneficial to them

during drought (Table 1). By far the most com monly

discussed agroforestry characteristic was that some

trees can be drought resistant and use less water than

other crops. According to a male farmer in Burat

(B11M) for some agroforestry trees, ‘‘their roots can

travel far and they can get water from far away. Their

roots dig down. It does not dry up quickly like some

other trees. Their roots go down very far to draw water

up from there.’’ Another male farmer in Burat (B6M),

stated that ‘‘even if there is wind or harsh sun and

drought, it [trees] thrives, it is able to thrive and it does

not die. It just has to smell water, a little bit, and it

thrives.’’ Lastly, a male farmer in Burat (B5M)

discussed how his trees remain green throughout the

seasons and reported that ‘‘During harsh sun, you can

see that they [trees] are still green. If it has matured, it

will be fine. Like these mangos, if they have matured

they will not dry up during the drought, they will

survive until the rains come again.’’

The second most commonly discussed agroforestry

characteristic was that a tree is able to produce fruit

year round, including during the dry season and during

drought. A female farmer in Burat (B4F) emphasized

this benefit from her papaya trees when she stated that,

‘‘ during drought, during every season it produces

fruit. You will not go without. These other trees, like

mangos, they only produce fruit once a year. Now the

tree that helps us a lot every time of the year, be it

during the rainy season or the dry season, it is these

papayas.’’ Farmers discussed that if they are able to

water their papaya trees, even minimally, they

continued to produce fruit. However, papaya was not

the only tree discussed, another farmer in Burat

(B16M) discussed planting pigeon peas because

‘‘ during drought is when they begin to produce peas.’’

The three other important characteristics of

drought-important trees discussed were the ability to

plant crops near trees, fast production and growth, and

good production. As most of these farmers have small,

diversified farms, it is important that trees can grow

next to other crops without taking up too much space

or resources. A male farmer in Burat discussed how

under his trees even ‘‘if I plant other things like

vegetables, it does not cost a lot of money because the

trees create a cool climate for the vegetables, they do

not suffer from the sun, and it also helps us to water the

vegetables less.’’ Fast growth was also an important

characteristic as emphasized by a male farmer in

Kinna (K10M) who discussed how ‘‘bananas, like if I

plant them today and then they grow for 9 months. If

9 months have passed, they begin to produce fruit.’’

Table 1 Characteristics of drought-important agroforestry trees

Characteristics # of interviews # of quotes

Uses less water/drought-resistant 20 67

Provide fruit during dry times of the year 14 32

Able to plant near crops 4 8

Fast production and/or growth 3 4

Good production 1 1

Included are the number of interviews where each characteristic was mentioned by the interviewee as well as the total number of

interview quotes that included each characteristics

123

Agroforest Syst

Flood

Contributions of agroforestry trees to reducing

sensitivity and increasing adaptive capacity to floods

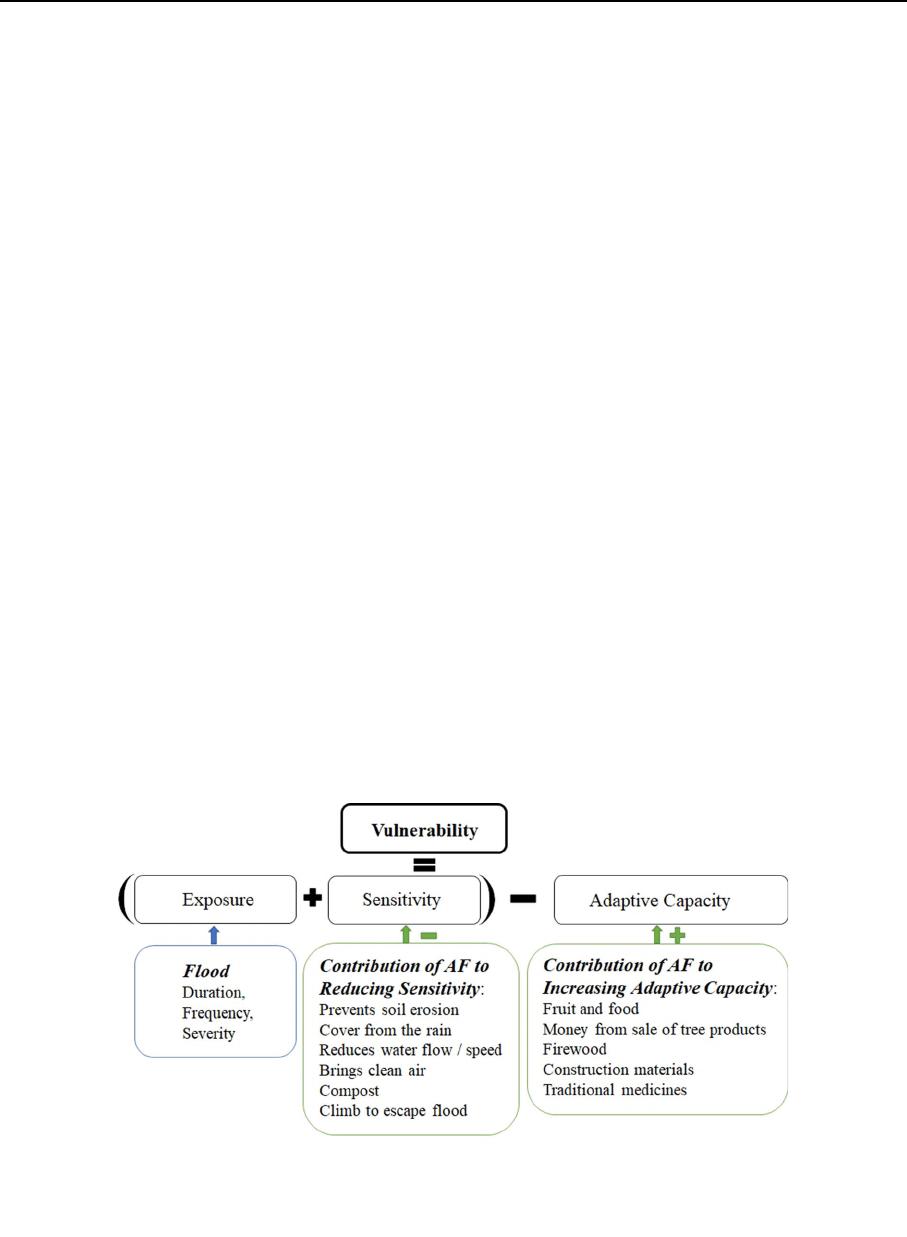

Figure 3 highlights the different themes that were

discussed about how agroforestry trees can contribute

to decreasing an interviewee’s sensitivity to flood

events, as well as to increasing their adaptive capacity

both before and during a flood. Similar to agro-

forestry’s contribution to decreasing sensitivity to

drought, in regards to floods the major contributions

were environmental, including reducing water flow

and speed across the land and preventing soil erosion.

As discussed by a male farmer in Kinna (K10M),

now the areas where you have trees, the soil and

nutrients are not washed away. These trees they

hold the soil with their roots, and this litter and

compost all of it, it stays and builds up here, that

is an advantage and it helps me a lot. That is, the

soil is not washed away, and soil from other

farms is washed here and it stays, all the soil and

nutrients stay on my farm.

Farmers in Burat had similar experiences and one male

farmer (B13M) stated that ‘‘If a flood happens, these

trees block the soil, their roots block the soil, they

prevent soil erosion.’’

Further, agroforestry trees were able to build

adaptive capacity by providing household necessities

like fruit, food, construction materials, firewood,

traditional medicines, as well as contributing finan-

cially through the sales of tree products. One female

farmer in Burat (B15F) stated that her trees ‘‘help her

with money and with food.’’ A male farmer echoed

these sentiments and stated ‘‘it helps us with food.

Because we can sell tree products and buy other

food.’’ A male farmer in Kinna (B5M) described how

‘‘ during floods my trees remain and I can eat the fruit,

even during a flood it flowers and we eat the fruit.’’ As

many illnesses can increase during floods one male

farmer in Burat (B3M) discussed the medicinal uses of

trees when he said that ‘‘yes it helps for medicine.

There is one type of tree that I have, I planted it over

there, it is called Muuvubau [Meru language for

‘medicine tree’]. It is very good for the body.’’

Importantly, the use of trees for firewood was

commonly brought up. Firewood can be particularly

important during the rainy periods when firewood can

be difficult to obtain because walking any distance

through the mud is difficult and most available wood is

wet. A male farmer in Burat (B2M) discussed how,

‘‘ Even I can sell firewood for money. During times of

flood, indeed you can get a good price for your

firewood, the prices are high. This is because of the

shortage of firewood during these times.’’ Another

male far mer in Burat (B16M) stated that ‘‘even during

the rains many of the branches break, and these

branches we use to make charcoal or we use it for

firewood for cooking.’’

Fig. 3 Contributions of agroforestry trees to reducing sensitiv-

ity and increasing adaptive capacity to floods. The contributions

are organized into benefits that reduce an interviewees’

sensitivity to floods, and those that increase their adaptive

capacity. The benefits included here are all the different benefits

that were discussed during the qualitative interviews. All related

themes or codes have been included

123

Agroforest Syst

Characteristics of flood-important trees

Table 2 includes the two characteristics of flood-

important trees that were discussed during the inter-

views. The most mentioned characteristic was flood-

resistant trees and/or that trees are not as easily

damaged as other crops during floods. A male farmer

in Kinna (K10M) stated that ‘‘even if water sits here on

my farm, it [trees] will not be destroyed’’, while a male

farmer in Burat (B13M) stated that ‘‘it is not easy for

my trees to be affected. You know like mangos and

these avocados they are not affected because they are

tall.’’

Other farmers discussed how many of their agro-

forestry trees are still able to produce fruit during

floods. For example, a female farmer in Burat (B4F)

said that ‘‘during floods we are happy because the

trees will get a lot of water and they will grow a lot of

large fruits.’’ A female farmer in Kinna (K8F)

discussed how even during flood events her papaya

trees ‘‘grow fruit very quickly’’, while a female farmer

in Burat (B4F) stated that ‘‘papaya helps us a lot. Here

it helps us a lot because these other trees only provide

fruit once a year.’’

Discussion

Drawing from empirical, qualitative research, this

paper highlights (1) the contributions of agroforestry

trees to reducing sensitivity and increasing adaptive

capacity to drought and flood events, as well as (2) the

key characteristics of drought-important and flood-

important agroforestry trees. In both drought and flood

events agroforestry had an important role to play in

reducing sensitivity, largely through improving envi-

ronmental conditions, and increasing adaptive capac-

ity by providing tree products and financial benefits.

Interestingly, the same benefits of agroforestry trees

(shade/cover, firewood, fruit, microclimate regulation,

soil erosion prevention) were commonly discussed by

interview participants for both drought and flood

events. Further, the critical aspects of both drought-

important and flood-important agroforestry trees were

that they were resilient to the impacts of these events.

However, there were a handful of benefits that were

drought-specific (windbreaker, livestock fodder) and

flood-specific (reducing speed of water flow).

The qualitative results found in Isiolo County,

Kenya are complementary to the current narrative of

the positive contributions of agroforestry to climate

change adaptation as well as the quantitative studies in

various geographic regions. For example, in Nepal,

Paudel et al. (2019) reported that 32% of survey

respondent’s ranked agroforestry as very important

during a drought and 51% ranked it as somewhat

important. Also, they found the major benefits of

agroforestry during a drought were fodder, firewood,

and fruit, while 80% of survey respondents reported

financial benefits (Paudel et al. 2019). These benefits

of agroforestry during drought were also highlighted

by the interviewee s in Isiolo County, Kenya, however

in Isiolo timber for construction materials was also

mentioned frequently. In Cameroon, Awazi et al.

(2019) and Nyong et al. (2019 ) found that 28% of

farmers were adopting agroforestry to build their

resilience to climate change because of the benefits of

food, fuelwood, building materials, and eros ion con-

trol. In Lower Nyando, Kenya, De Giusti et al. (2019)

emphasized the importance of financial benefits and

how agroforestry trees were viewed as ‘money in the

bank.’

In relation to the environmental benefits of agro-

forestry decreasing sensitivity to climate change

impacts, Tran and Brown (2019) found that in

Vietnam, smallholder farmers also reported that the

ecosystem services provided by agroforestry trees

helped them adapt to the impacts of climate change.

Table 2 Characteristics of flood-important agroforestry trees

Characteristics # of interviews # of quotes

Not easily damaged/flood-resistant 9 21

Fast or continuous production 5 5

Included are the number of interviews where each characteristic was mentioned by the interviewee as well as the total number of

interview quotes that included each characteristics

123

Agroforest Syst

Additionally, Gomes et al. (2020) reported that coffee

agroforestry with 50% shade cover can create suit-

able microclimates in order to maintain current areas

of coffee production despite projections in climate

changes. This supports the findings of this study as

shade was mentioned frequently both for creating

suitable climates for growing crops, as well as cool

places for people to relax. Importantly, there is a lack

of social science research about how agroforestry trees

can reduce smallholder sensitivity to floods and

droughts, and instead most relevant work comes from

the natural sciences and agronomy (for example, Lal

et al. 1991; Lin 2010; Gomes et al. 2020). Thus, this

study provides novel and important insights using

qualitative social science methods.

In addition to increasing our understanding of the

‘lived’ experience of smallholder farme rs in Kenya

with utilizi ng agroforestry trees during drought and

flood events, this study also highlights the usef ulness

of drawing from the vulnerability framework as an

organizational tool for understanding specifically how

agroforestry can contribute to climate change adapta-

tion efforts by organizing the benefits of agroforestry

into the categories of sensitivity and adaptive capacity.

For example, interviewees clearly discussed how the

environmental benefits of agroforestry have decreased

their sensitivity to both droughts and floods by

providing shade and preventing soil erosion. Also,

research participants discussed in depth how agro-

forestry has helped them to better cope with and adjust

to thes e natural hazards by providing household

necessities and financial capital in times of need.

These benefits of agroforestry clearly fit into the

conceptualizations of sensitivity (Adger 2006; Smit

and Wandal 2006) and adaptiv e capacity (Smit and

Wandal 2006; Adger 2006; IPCC 2014) as compo-

nents of vulnerability. Thus, utilizing vulnerability as

an organization framework could be used to better

understand the contributions of agroforestry to vul-

nerability and adaptation in other geographic contexts,

and also in research exploring other potential adapta-

tion strategies and livelihood activities.

Policy implications

Understanding what types of adaptation strategies and

livelihood activities are effective for helping small-

holder farmers better cope and prepare for drought and

flood events is critically important to climate change

adaptation projects and policies, and this study

highlights how qualitative research can contribute to

this goal. Agriculture is often considered the liveli-

hood strategy most vulnerable to climate change, and

thus better understanding how to adapt agriculture to

the impacts of climate change is critica l for both the

livelihoods of smallholder farmers and global food

security efforts. Thus, the findings presented here may

provide some guidance for future policies aimed to

improve climate change adaptation efforts, as well as

provide an approach to assess different agricultural

adaptation strategies and livelihood activities drawing

from the concepts of vulnerability and adaptation. For

example, certain agroforestry trees can reduce vulner-

ability to climate change impacts by increasing

adaptive capacity and reducing sensitivity. Therefore,

the practical and policy implications of this study may

be broad and far-reaching in terms of promoting

agroforestry as an effective climate change adaptation

strategy that reduces smallholder farmer vulnerability.

However, it is important that any agroforestry policies

or projects take into account the local environmental,

social, and economic contexts when promoting certain

agroforestry practices and/or tree species for climate

change adaptation.

Conclusions

Agroforestry is praised as a sustainable livelihood that

can assist smallholder farmers adapt to climate change

and climate variabilit y in Africa. This qualitative

study has highlighted the specific contributions of

agroforestry to climate change adaptation on small-

holder farms in Isiolo County, Kenya, with a focus on

floods and droughts. Drawing from the concepts of

vulnerability and adaptation, agroforestry can con-

tribute to both reducing an individual’s sensitivity to

natural hazards, while also increasing their adaptive

capacity. During drought agroforestry trees were

reported to reduce sensitivity by providi ng shade for

people and crops, serving as a windbreaker, attracting

the rain, preventing soil erosion, and providing

compost/fertilizer; as well as increasing adaptive

capacity by providing fruit and food, firewood,

construction mater ials, livestock fodder, beautification

of the farm/home plots, and money from the sales of

tree products. Characteristics of drought-important

123

Agroforest Syst