The Scissors Model of Microcrack Detection in Bone: Work in Progress

David Taylor

1

, Lauren Mulcahy

1,2

, Gerardo Presbitero

1

, Pietro Tisbo

1

, Clodagh Dooley

1

, Garry

Duffy

2

and T.Clive Lee

2

1

Trinity Centre for Bioengineering, Trinity College, Dublin 2, Ireland.

2

Department of Anatomy, Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, Dublin, Ireland.

ABSTRACT

We have proposed a new model for microcrack detection by osteocytes in bone.

According to this model, cell signalling is initiated by the cutting of cellular processes which

span the crack. We show that shear displacements of the crack faces are needed to rupture these

processes, in an action similar to that of a pair of scissors. Current work involves a combination

of cell biology experiments, theoretical and experimental fracture mechanics and system

modelling using control theory approaches. The approach will be useful for understanding

effects of extreme loading, aging, disease states and drug treatments on bone damage and repair;

the present paper presents recent results from experiments and simulations as part of current,

ongoing research.

INTRODUCTION

The idea for the so-called “scissors model” first came about in 2001: the concept has now

appeared in a number of publications [1-5] and currently is being actively researched by a team

which includes materials scientists, cell biologists, microscopists and experts in engineering

control theory. In this paper we take the opportunity to present for the first time some of our

most recent results, from experimental activities which are still ongoing. Because this paper was

written to form part of a special symposium devoted to body tissues under extreme loading and

disease, we have pointed out those areas where our approach has contributed, or may contribute

in the future, to the understanding of bone mechanics under these particular conditions. However

it should be emphasised that we have still a lot to do in the future in considering these particular

aspects in more detail.

REPAIR OF BONE MICRODAMAGE: DOES IT MATTER?

Before considering the detection and repair of small cracks in bone – which is the subject

of this paper – it is worth asking: “Does it matter?”. Do these cracks threaten the structural

integrity of bone in normal use? This is a question which we can answer using a different model

which we have developed over the last 12 years, a phenomenological model which describes

fatigue damage and repair in bone using the available data, which are now quite extensive, and

including statistical scatter via the Weibull approach. This model has been described in a number

of previous publications [6-9]; it does not consider at all the underlying physical mechanisms,

but it is able to predict experimental data from different animals and different test protocols

Mater. Res. Soc. Symp. Proc. Vol. 1274 © 2010 Materials Research Society 1274-QQ08-01

rather well, it gives reasonable predictions of phenomena such as the effect of exercise on stress

fracture risk and as a result has recently has been employed in the field of sports science [10].

Here we use the model to consider the risk of fatigue failure in a typical bone, loaded

with physiologically normal stresses, comparing bone from a typical individual capable of

repairing small cracks as they initiate, and an individual suffering from a disease state in which

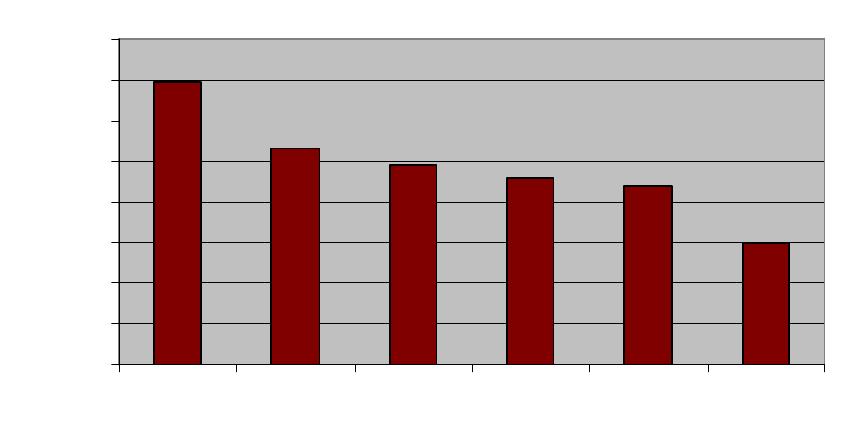

this repair process does not occur. Figure 1 below presents the results in terms of a stress

reduction factor, defined as the ratio between the stresses in the normal person and in the

diseased person which give the same fatigue behaviour. The behaviour chosen was a 1% risk of

fatigue failure per bone during the lifetime of the person, as this is typical of the actual rates of

failure of bones in primates in the wild [11]. The stress factor is thus the same as the factor by

which the compromised individual would have to reduce the forces on their bones in order to

prevent failure from occurring.

Obviously the magnitude of this factor depends on the activity level of the individual:

more active individuals will be more at risk, especially those engaging in extreme loadings such

as professional athletes and soldiers. We considered six different activity levels as defined by

Whalen et al [12]. The results show that repair has a very strong influence: for normal or active

individuals it’s necessary to reduce loadings by a factor of the order of 2 to 3 if repair is not

available. In practice this would mean that any activity more strenuous than slow walking would

be dangerous.

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

3.5

4.0

Athletic Act.+Ex Active Normal Sed + Ex Sedentary

Stress Factor

Figure 1: Estimated stress factor for similar fatigue performance of bones, comparing normal

individuals and those having no ability to repair microcracks. Six different activity levels are

considered, after Whalen et al [12].

MICROCRACK DETECTION: THE SCISSORS MODEL

Many workers have contributed to what is now quite an extensive research activity on the

initiation, growth and repair of microcracks in bone. A recent review provides a summary of this

work [13]. In brief, cyclic loading in vivo causes cracks to initiate in cortical and cancellous

bone. These cracks are typically elliptical in shape, being elongated in the direction

approximately parallel to the bone’s longitudinal axis due to the material’s anisotropy. On

average the length (from tip to tip) of such a crack is about 100µm on its minor axis and about

400µm on the major axis. We will refer to the minor axis length in what follows because this is

the length which appears on transverse sections of bones and so is the value most often reported

as the crack length. . The number density of cracks varies greatly but can be in excess of 1 crack

per cubic millimeter. In vivo crack lengths rarely exceed 200µm, but in cyclic loading tests

conducted on bones ex vivo, a proportion (10-20%) of cracks are found to propagate by fatigue

mechanisms, one crack eventually causing failure. Based on our experimental experience and

some simple fracture mechanics calculations, one can form a picture of the risk which these

cracks pose. Very small cracks (say less than 30µm) pose a negligible risk; cracks of the typical

length of 100µm can be tolerated but would pose a risk in individuals engaging in strenuous

activities; longer cracks (greater than about 300µm) will grow quite quickly under normal in vivo

stresses and so must be detected and removed to avoid failure. Thus we have a kind of

“specification” for the maintenance system which operates in our bones.

The repair system is quite well described: it consists of two types of cells working

together: osteoclasts remove old, damaged bone and osteoblasts fill in the gap by making new

bone. Currently though, we don’t understand how microcracks are detected in the first place.

There are a number of theoretical models under investigation (see [13]) most of which work

from the idea that the crack affects the flow of fluid which is constantly seeping through the

porous bone matrix. Our model is quite different: we considered whether the crack would

damage any of the cells (osteocytes) which live in bone. We concluded that the cells themselves

were unlikely to be fractured by the locally elevated strains near the crack, but that fracture could

occur in the long, thin extensions known as cellular processes, which link cell to cell in a

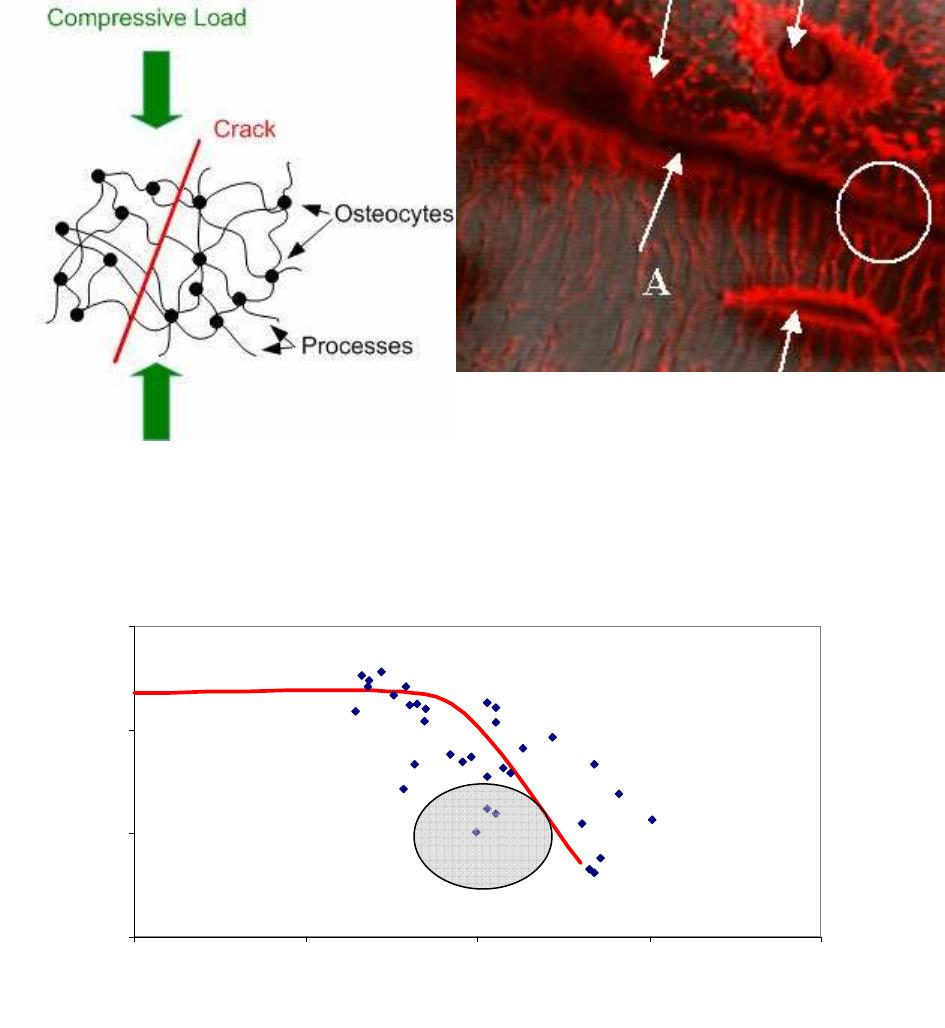

network known as the “syncytium”. Each cell has about 100 such processes (see fig.2). We

proposed that where a process passes across a crack, the displacements of the crack faces could

cause rupture (fig.2). Theoretical analysis using fracture mechanics found that this was most

likely to occur due to shear loadings, especially in combination with compressive forces across

the crack faces. In fact most cracks in bone experience this combination of shear and

compression, due to the typical loadings and crack orientations which occur.

EXPERIMENTAL WORK: MICROSCOPY

The photograph in fig.2 represents the highest level of resolution which we were able to

achieve using laser confocal microscopy. To obtain more precise information we examined

cracks at higher magnification using scanning electron microscopy. We found fibrous features

spanning crack faces: by staining the samples with Phalloidin to reveal the cellular material, we

demonstrated that the great majority of these were cellular processes. This is interesting in itself

because other workers have proposed that these features are collagen fibrils and have argued that

they have a significant toughening effect. For the bone samples which we examined, at least,

there were very few collagen fibrils spanning cracks: this finding could be important because

cellular processes would be too weak to contribute any significant toughening effect.

We first examined ovine bones which had been taken from animals used in other

experiments, which were known to have had only normal loading activities during life. We saw

both intact and broken processes across crack faces; we counted the intact ones because it was

difficult to count the broken ones reliably.

Figure 2: Schematic illustrating the Scissors Model. Laser scanning confocal image of a bone

sample (width of picture = 50µm). Three osteocyte cells can be seen (arrowed) with many

processes coming from them. A crack (arrowed, A) crosses the picture: some cellular processes

cross the crack and remain intact (circled) whilst others have ruptured.

1

10

100

1000

1 10 100 1000 10000

Crack Length 2a (um)

Number of Intact Processes

per mm

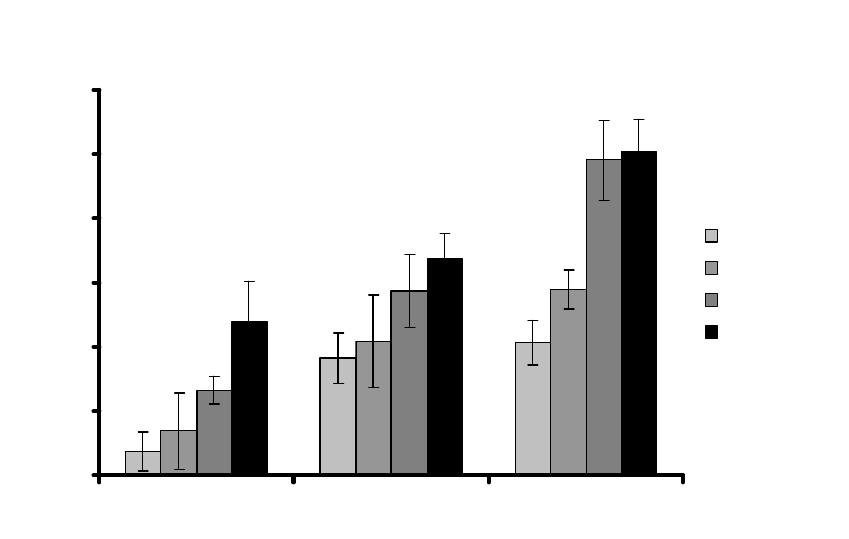

Figure 3: Experimental data (points) recording the number of intact processes per mm of crack

length, as seen on transverse sections of ovine bone after normal in vivo loading. Predictions of

our theoretical model (line). Recent data from samples subjected to loadings greater than in vivo

levels (grey circle).

Figure 3 shows the results, plotting the number of broken processes per millimeter of crack

length, as a function of crack length. The figure also shows the predictions of our theoretical

model, using a typical osteocyte density (20,000/mm

3

) and assuming normal in vivo loading

activities. There is a lot of scatter in the data points from individual cracks, but it’s clear that

longer cracks have relatively fewer unbroken processes and that this behaviour is well predicted

by the model. Figure 3 also indicates some more recent data obtained from ovine bone samples

which had been subjected to cyclic loading in the laboratory at stress levels greater than

experienced in vivo. This data, currently incomplete, is indicated by the grey circle, showing that

for crack lengths around 100µm there are many more broken processes. All of this is nicely in

accordance with our “specification” above: for in vivo loading there is a threshold at somewhat

less than 100µm, below which no processes break and so the crack would be undetectable. This

threshold shifts downwards if higher stresses are applied which would make the 100µm cracks

potentially much more dangerous.

EXPERIMENTAL WORK: IN VITRO CELL STUDIES

In parallel with the above work we have been conducting studies on living cells cultured

in vitro. We used MLO-Y4 cells, a line of cells developed for laboratory study, which have been

shown to have many properties similar to those of natural osteocytes, but which are easier to

culture and maintain for experimental work. We cultured these cells in 3D gels in pots of

diameter 10mm, depth 10mm. A crack-like planar defect was introduced, width 5mm, depth

10mm, of varying thickness, using wires of different diameters. We made various measurements

to detect the production of different proteins which are known to play roles in cell signalling. As

figure 4 shows, we found that after introducing the cracks, there was a significant increase in the

production of RANKL, a protein which is known to stimulate the production of osteoclasts. This

is highly significant because osteoclast production is the first step in the repair process.

RANKL promoter activity: microdamage 160-400 microns

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

24 hour 48 hour 72 hour

Promoter activity: Luminescence

Control

160 microns

300 microns

400 microns

Figure 4: Production of RANKL by osteocyte-like cells in vitro at various times following

introduction of a crack-like defect 5mm x 10mm, various widths (160-400µm), compared to

undamaged controls.

These MLO-Y4 cells are similar to real osteocytes in bone, but there are some important

differences, which we investigated experimentally. We found that real osteocytes have an

average separation of 37µm and have typically 100 processes per cell. Our MLO-Y4 cells, on the

other hand, had a separation of 100µm and only 13 processes per cell on average. This means

that the “crack” created in our cell experiments is (in terms of the number of processes which

cross it) equivalent to a much smaller crack in bone: in fact it is equivalent to a crack of length

500µm, somewhat larger than the typical 100µm, but more comparable than first appears. Given

that our experimental cells are 100µm apart, the 160µm wire is probably cutting through

processes but not rupturing cells (though obviously this is something we need to check) whilst

the thicker wires have a greater effect because they probably are also breaking cell bodies,

something which we believe does not happen in bone.

THEORETICAL MODEL

A theoretical model, written in the form of a MATLAB simulation, was first developed some

years ago [14; 15], based around a fracture mechanics description of fatigue crack propagation in

short and long cracks. This model is currently being improved to make several aspects more

realistic. One feature which required attention was the simulation of crack initiation, which is a

common problem in fracture mechanics models because we have no real theoretical framework

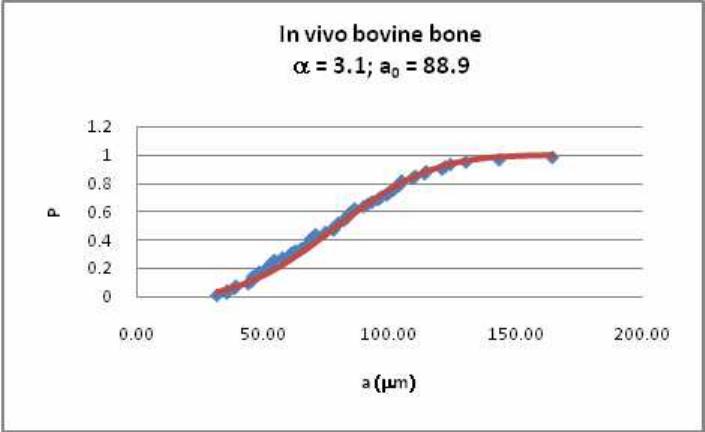

for this stage of a crack’s life. To circumvent this problem we examined the data on microcrack

lengths in bone samples taken from our own work and other sources. We found that the

distribution of crack lengths can be described as a two parameter Weibull distribution, whose

constants change in a predictable manner with stress level, number of cycles, animal type etc.

Figure 5 shows an example of one of these distributions. We intend to incorporate this

information into our model, to provide a realistic description of the lengths and numbers of

cracks which initiate; these cracks can then be allowed to grow using standard short-crack

growth formulae.

Figure 5: Example of our analysis of microcrack data, showing a two-parameter Weibull fit to

the crack length distribution in bovine bone samples subjected to normal in vivo loadings.

DISCUSSION

As mentioned above, this paper is very much a description of work in progress rather

than of a finished project. Results to date are very encouraging, suggesting that several aspects of

our scissors model can be demonstrated in experiments and predicted theoretically. For example,

we have now shown conclusively that cellular processes can span cracks, remaining intact in

small cracks under in vivo loadings and breaking in increasingly large numbers if the crack

length or the stress increases. Through our cell experiments we have demonstrated that planar

defects of approximately the same size as microcracks (when differences in the cell types are

accounted for) cause cells to increase production of a substance which stimulates bone-resorbing

cells. We aim to incorporate all of these effects into our theoretical model, thus building a

simulation of the entire feedback loop whereby microdamage is detected and repaired. One

important and difficult step in the development of that model is the simulation of crack initiation:

this problem has recently been overcome by studying and modeling crack length data.

What consequences does this work have for tissues under extreme loading and disease?

High levels of loading, equivalent to very strenuous or active lifestyles, are known to give rise to

stress fractures. This is a major problem, for example, in military recruits, football players and

racehorses. Stress fractures occur because fatigue cracks are growing so quickly that the time

between detection and repair is no longer sufficient to prevent the development of a macrocrack.

Stress fractures can also happen as a result of diseases such as osteoporosis, which may affect the

detection and repair system and also the mechanical properties of the bone itself. Drug

treatments for osteoporosis work in different ways, targeting different parts of the feedback

system. In all of these cases an understanding of the mechanisms of crack detection and repair is

clearly vital.

Further work is required to confirm the scissors mechanism and to investigate it in more

detail; this work is ongoing at present.

CONCLUSIONS

1. The repair of microdamage by living bone is vital to maintain the necessary level of

structural integrity which allows us to go about everyday life without suffering fatigue failures.

2. The scissors model, in which cracks are detected because they cause rupture of cellular

processes, is demonstrated to be a plausible mechanism.

3. In particular, the numbers of broken processes rise significantly when crack lengths

increase and when stresses increase, within and just above normal physiological levels.

4. In addition, crack-like defects introduced into cell cultures cause increased production

of RANKL, which is known to stimulate osteoclast production.

5. Microcracks in bone have a length distribution which can be described by the two-

parameter Weibull equation: this finding is useful for the simulation of fatigue crack initiation in

our theoretical model.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by Science Foundation Ireland as part of the Research Frontiers

Programme, grant number 08-FRP-ENM991. We are grateful to Prof.Bonewald for permission

to use the MLO-Y4 cell line, to Teuvo Hentunen and colleagues for advice concerning the cell

culture experiments, and to David Burr and colleagues for generously sharing their microcrack

data with us.

REFERENCES

1. Taylor, D., Hazenberg, J. G., and Lee, T. C., "The cellular transducer in damage-

stimulated bone remodelling: A theoretical investigation using fracture mechanics,"

Journal of Theoretical Biology, Vol. 225, No. 1, 2003, pp. 65-75.

2. Hazenberg, J. G., Freeley, M., Foran, E., Lee, T. C., and Taylor, D., "Microdamage: a

cell transducing mechanism based on ruptured osteocyte processes," Journal of

Biomechanics, Vol. 39, 2006, 2096-2103.

3. Hazenberg, J. G., Taylor, D., and Lee, T. C., "The role of osteocytes in functional bone

adaptation," BoneKey Osteovision, Vol. 3, 2006, pp. 10-16.

4. Hazenberg, J. G., Taylor, D., and Lee, T. C., "The role of osteocytes in preventing

osteoporotic fractures," Osteoporosis International, Vol. 18, 2007, pp. 1-8.

5. Hazenberg, J. G., Hentunen, T., Heino, T. J., Kurata, K., Lee, T. C., and Taylor, D.,

"Microdamage detection and repair in bone: fracture mechanics, histology, cell biology,"

Technology and Health Care, Vol. 17, 2009, pp. 67-75.

6. Taylor, D. and Kuiper, J. H., "The prediction of stress fractures using a 'stressed volume'

concept," Journal of Orthopaedic Research, Vol. 19, No. 5, 2001, pp. 919-926.

7. Taylor, D., "Scaling effects in the fatigue strength of bones from different animals,"

Journal of Theoretical Biology, Vol. 206, No. 2, 2000, pp. 299-306.

8. Taylor, D., "Fatigue of bone and bones: An analysis based on stressed volume," Journal

of Orthopaedic Research, Vol. 16, No. 2, 1998, pp. 163-169.

9. Taylor, D., Casolari, E., and Bignardi, C., "Predicting stress fractures using a

probabilistic model of damage, repair and adaptation," Journal of Orthopaedic Research,

Vol. 22, 2004, pp. 487-494.

10. Edwards, W. B., Taylor, D., Rudolphi, T. J., Gillette, J. C., and Derrick, T. R., "Effects

of stride length and running mileage on a probabilistic stress fracture model," Medicine

and Science in Sports and Exercise, Vol. 41, No. 12, 2009, pp. 2177-2184.

11. Currey, J., Bones: Structure and Mechanics, Princeton University Press, USA 2002.

12. Whalen, R. T., Carter, D. R., and Steele, C. R., "Influence of physical activity on the

regulation of bone density," Journal of Biomechanics, Vol. 21, No. 10, 1988, pp. 825-

837.

13. Taylor, D., Hazenberg, J. G., and Lee, T. C., "Living with Cracks: Damage and Repair in

Human Bone," Nature Materials, Vol. 2, 2007, pp. 263-268.

14. Taylor, D. and Lee, T. C., "Microdamage and mechanical behaviour: Predicting failure

and remodelling in compact bone," Journal of Anatomy, Vol. 203, No. 2, 2003, pp. 203-

211.

15. Taylor, D. and Lee, T. C., "A crack growth model for the simulation of fatigue in bone,"

International Journal of Fatigue, Vol. 25, No. 5, 2003, pp. 387-395.