Hypocholesterolemic Effect of Potential Probiotic Lactobacillus

fermentum Strains Isolated from Traditional Fermented Foods

in Wistar Rats

Pooja N. Thakkar

1,2

& Ami Patel

3

& Hasmukh A. Modi

1

& Jashbhai B. Prajapati

2

#

Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, part of Springer Nature 2019

Abstract

The current research project was undertaken to explore the therapeutic potential of two potent probiotic Lactobacillus fermentum

strains, i.e., PD2 and PH5 in a hyperlipemic healthy adult Wistar rat model, with a particular focus as biotherapeutics for the

management of high choles terol in Indian population. Rat s fed on cholesterol-enriched diet supplemented with potential

probiotics strain Lactobacillus fermentum PH5 significantly affected serum lipid profile by reducing serum cholesterol

(67.21%), triglycerides level (66.21%), and LDL cholesterol level (63.25%) in comparison to rats that received cholesterol-

enriched diet (Model) only. Both the strains decreased the cholesterol levels in liver compared with Model group, but PH5 was

found to be more effective (30.65% reduction) in liver total cholesterol (TC) lowering action. In addition, the fecal coliforms were

significantly reduced besides increased LAB in feces of rats receiving probiotic curd having Lactobacillus fermentum PH5. Our

results demonstrated that supplementation with either of the two strains was efficient in reducing serum cholesterol, LDL-

cholesterol and TG concentrations in rats compared to those fed the same high-cholesterol diet but without LAB

supplementation.

Keywords Hypocholesterolemic effect

.

Probiotics

.

Lactobacillus fermentum

.

Bile salt hydrolase activity

.

Wistar rats

Introduction

The incidence of hypercholesterolemia is increasing swiftly

with the improvements of people’s livin g standards and

amendments in lifestyles. Elevated serum cholesterol level is

usually considered to be the most imperative risk factor for the

development of cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), such as ath-

erosclerosis, hypertension, coronary heart disease, and stroke.

Both drug therapy and non-pharmacological approaches, in-

cluding dietary interventions, behavior modification, and reg-

ular e xercise , are com mon strategies to lower cholesterol

levels. Current drug therapies (i.e., statins), despite the proven

cholesterol lowering ability, with their high relative costs and

associated side effects, are not viewed to be optimal long-term

answers [1, 2]. It is more attractive to develop possible strat-

egies and safer alternative thera pies by modulating diet

through probiotic interventions that could be promising and

cost effective in lowering cholesterol [3].

Previous in vitro screening experiments revealed that strain

PD2 (dosa batter isolate) and strain PH5 (handva batter iso-

late) were able to tolerate maximum bile concentration, pro-

duce bile salt hydrolase (BSH) enzyme, and could

deconjugate bile salts like sodium taurocholate (ST) [4, 5];

they were identified as Lactobacillus fermentum by molecular

typing methods. These potential probiotic strains were inves-

tigated for probiotic candidatures using obligatory tests as

well as evaluated for safety aspect by performing amino acid

decarboxylating activity (production of biogenic amines), he-

molysis activity, antibiotic resistance, and gelatinase activity

[4–6]. Both the strains showed negative response for all these

tests indicating possible safe use for further investigations.

Further, with respect to direct cholesterol assim ilation

(in vitro), PH5 showed a m aximum reduction of 76.85%

followed by PD2 69.66% compared to control by utilizing

human plasma as a source of cholesterol [4, 5]. Thus, the study

was undertaken to explore the therapeutic potential of

* Ami Patel

amiamipatel@yahoo.co.in; ami@midft.com

1

Department of Life Sciences, Gujarat University, Ahmedabad, India

2

Department of Dairy Microbiology, SMC College of Dairy Science,

Anand Agriculture University, Anand, India

3

Division of Dairy Microbiology, Mansinhbhai Institute of Dairy &

Food Technology-MIDFT, Mehsana, Gujarat State, India

Probiotics and Antimicrobial Proteins

https://doi.org/10.1007/s12602-019-09622-w

probiotic dahi made from two potent probiotic Lact.

fermentum strains, i.e., PD2 and PH5 in a hyperlipemic

healthy adult Wistar rat mo del, with a particular fo cus as

biotherapeutics for the management of high cholesterol in

Indian population.

Materials and Methods

Lact. fermentum PD2 [gene accession no.KR612224] and

PH5 [gene accession no.KR612226] were isolated previously

from the batter of traditional Indian fermented nondairy prod-

ucts [4–6]. Further, both these strains having potential probi-

otic attributes were selected for current investigation on the

basis of their better abilities to lower cholesterol in in vitro

trials. For the preparation of probiotic (curd) diet, overnight

grown test cultures, i.e., Lact. fermentum PD2 and PH5 were

pelleted at 5000 rpm for 30 min at 4 °C and washed twice with

saline. The cell pellet of each culture was inoculated into ster-

ile reconstituted skim milk and incubated at 37 °C to achieve

curdling. The curd samples from each culture PD2 and PH5

were stirred and diluted to attain the final concentration 10

7

and 10

9

CFU/g as two define doses, respectively. The concen-

trations of the bacterial strains were maintained constant and

checked by plating on selective (MRS) agar media over the

fermentation time during each trial.

Experimental Animals

Healthy adult Wistar albino rats (Either sex), 4–6 weeks old

weighing 200–250 g, were used for the present study. The

animals were housed under well-controlled conditions of tem-

perature (22 ± 2 °C) and humidity (55 ± 5%) for 12:12 h light-

dark cycle. Animals had free access to conventional laborato-

ry diet (purchased from Pranav Agro Pvt. Ltd.) and tap water

ad libitum throughout the adaptation period. The protocol of

the experiment in this thesis was approved by Institutional

Animal Ethical Committee (IAEC) of Anand Pharmacy

College (Protocol No: APC/2015-IAEC/1504).

Experimental Design and Diet

At the end of the adaptation period, animals were randomly

selected, weighed, and divided into seven different groups

with six animals in each group with their assigned diet as

shown in Table 1. Adult Wistar albino rats of Group B (mod-

el), Group C (Standard) a nd other experimental groups

(Groups D, E, F and G) were made hyperlipidemic by the oral

administration of high-fat diet (Atherogenic diet) by mixing

with regular pellet diet. The base composition of the athero-

genic (hyperlipidemic) diet included cholesterol, cholic acid,

coconut oil, sucrose, and normal laborat ory diet 2%, 1%,

10%, 40%, and 47%, respectively.

Rats of the experimental groups (Groups D, E, F, and G)

were also fed with 2 ml probiotic (stirred curd) in two doses

once daily in the morning through oral feeding/gastric incu-

bation for 28 consecutive days. Control and Model groups

received an equivalent amount of normal saline. Rats of

Group C were treated with markedly available standard drug

atorvastatin (10 mg/kg of their body weight) only to compare

effect of treatment with our probiotic solutions. During the

entire course of the experiment, the rats had free access to

water and to the group specific diet (20 g/100 g body weight

per day). The experiment was carried out for 4 weeks. Food

intake of the animal was observed daily whereas the body

weight was determined weekly. After the feeding period, the

rats were euthanized and the weight of the visceral organs

(Liver, Kidney, Spleen, Lungs and Heart) and Fat pad (mes-

enteric, perirenal, and epididymal white adipose tissues) was

measured.

Assay for Serum Lipid

Blood samples of the animals of each group were collected at

0 day and the end of the experiment on 28th day. The

overnight-fasted animals were given light anesthesia and

blood was collected from the retro orbital plexus with capil-

lary tubes. Each sample of serum was analyzed for serum total

cholesterol (TC), serum high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

(HDL-C), serum low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C)

and triglycerides (TG) using commercially available kits

(Coral Clinical Systems, Goa) based on the enzymatic oxida-

tion of these molecules. Atherogenic indexes (TC/HDL-C and

LDL-C/HDL-C ratios) were then calculated [1, 2].

Assay for Liver Cholesterol and Triglycerides

After euthanasia, the livers from all groups were collected,

perfused, rinsed with physiological saline solution, weighed,

and homogeniz ed. Liver tissues were extracted following

standard procedure of Shakuto et al. [7]withslightmodifica-

tions. An aliquot extract was supplied for lipids determina-

tions by observing absorbance in UV–Visible spectrophotom-

eter (UV-1601 Shimadzu, Japan) using standardized commer-

cial kit (Coral Clinical Systems, Goa).

Histopathological Analysis

Rat livers from each group were dissected out and frozen

rapidly to about −20 °C till use. All the tissues are then placed

in neutral formaldehyde (10%), embedded in paraffin and

processed into 5 μm sections for light microscopy according

to the routine procedures. The sections were stained with

hematoxylin-eosin (HE) for histological assessment [8].

Probiotics & Antimicro. Prot.

Analysis of Fecal Samples for Fecal Sterol, Fecal

Water, and Fecal Microflora

Fecal droppings were collected during the last 2 days of life of

rats, and fecal neutral and acidic sterols were extracted with

slight modifications as suggested by Xi e et al. [2]. In the

middle of the 4th weeks, rat feces were amassed, weighed,

and dried at 80 °C in a vacuum drying oven until a constant

weight was achieved within 24 hours, and then reweighed.

Fecal water content was calculated as suggested by Lee

et al. [9]. Fecal water content (%) = [(weight before drying-

weight after drying)/weight before drying] × 100.

Each sample was homogenized using a mortar and pestle

using sterile PBS. Subsequent tenfold serial dilutions of each

sample were plated in duplicate as per the method of Xie et al.

[2]. Eosin methylene blue (EM B) agar was used for

Escherichia coli, Violet red bile agar was utilized for coli-

forms, and MRS agar was used for total lactobacilli. Plates

of total lactobacilli were incubated anaerobically at 37 °C for

48 h, while plates for the enumeration of E. coli and coliforms

were incubated aerobically at 37 °C for 48 h. The numbers of

colony-forming units (CFU) are expressed as log10 CFU per

g.

Results and Discussion

The in vivo effect of two nondairy origin potent probiotics

Lact. fermentum (PD2 and PH5) was analyzed to determine

how their cholesterol metabolism would affect hyperlipidemic

Wistar albino rats as the model system in current approach.

Effect of Potential Probiotic on Anthropogenic

Parameters

All the experimental rats utilized in this study appeared

healthy throughout the whole feeding period of 28 days.

Their body weight, fat pad, and food consumption were cal-

culated and recorded for all the groups during the experimen-

tal period as indicated in Table 2.

The initial body weight of rats showed no significant dif-

ference among groups. After 28 days of experimental period,

the rats in group B (Model) exhibited an increasing trend in

body weight (289.78 ± 13.9 g), probably as a consequence of

their greater calorie intake, due to the greater energetic density

of the high cholesterol diet compared with group A (Normal)

which fed a regular diet. While feeding probiotic 10

7

and 10

9

CFU/ml of Lact. fermentum PD2 and PH5, other experimental

groups (groups labeled D, E, F, G) showed an increase in the

final body weight compared to their initial weight. Vijayendra

and Gupta [10] reported Lact. acidophilus fermented dahi

helped to improve body weight gain in rats. Food consump-

tion was found significantly less (80.39 ± 4.16) in group B

(Model) compared to group A (normal) (100.57 ± 10.29). All

probiotic fed groups (D, E, F and G) exhibited equal food

consumption efficiency ratio as shown in Table 3.Foodeffi-

ciency % was calculated on the basis of weight gain (g) and

mean food consumption.

After the rats were killed, fat pad (mesenteric, perirenal,

and epididymal white adipose tissues) was separated and

weighed. The weight of fat pad was observed to be signifi-

cantly raised in group B (Model) 3.42 vs. 2.97 g. Group C

(Standard) and group G (PH Test dose 2) demonstrated similar

weight of fat pad (p > 0.05), 2.84 and 2.92 g respectively.

Lowest fat pad weight was found to be observed in case of

PD Test dose 1 (2.06 g).

Effect of Potential Probiotic on Weights of Various

Organs

After the rats were killed, the visceral organs (liver, kidney,

spleen, heart, lungs) were collected and weighed as shown in

Table 3. The rats had the lowest liver weight in group A

(Normal) while significantly highest liver weight in group B

(Model). Although administrating probiotic dahi alters the liv-

er weight. Group D (Lact. fermentum PD2 dose 1) significant-

ly lowered liver weight as compared with the group B

(Model). Group E, F, and G also lowered the liver weight,

but without statistical significance.

There were no significant difference in the weight of hearts,

lungs, and kidneys among the seven groups. Significant

Table 1 Experimental groups

with their respective diet

Group name Diet and dose

A Normal control Regular standard diet pellet

B Model control Atherogenic diet (hyperlipidemic diet)

C Standard control Atherogenic diet + standard antihyperlipidemic drug (atorvastatin 10 mg/kg)

D Test dose 1- PD2 Atherogenic diet + curd having 10

7

probiotic strain PD2

E Test dose 2- PD2 Atherogenic diet + curd having 10

9

probiotic strain PD2

F Test dose 3- PH5 Atherogenic diet + curd having 10

7

probiotic strain PH5

G Test dose 4- PH5 Atherogenic diet + curd having 10

9

probiotic strain PH5

Probiotics & Antimicro. Prot.

differences b etween spleen o rgans weight of group A

(Normal) and group B (Model) control was observed, with

insignificant changes in treatment groups.

Effect of Potential Probiotic Feeding on Serum Lipid

Profile

Reduction of serum total cholesterol (TC) and LDL-C and

increase in HDL-C may be fundamental treatment opinion

for CVDS. The effect of dietary treatments (probiotic curd)

on serum lipid profile (serum total cholesterol, triglycerides,

HDL-cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol) has been recorde d in

Table 4.

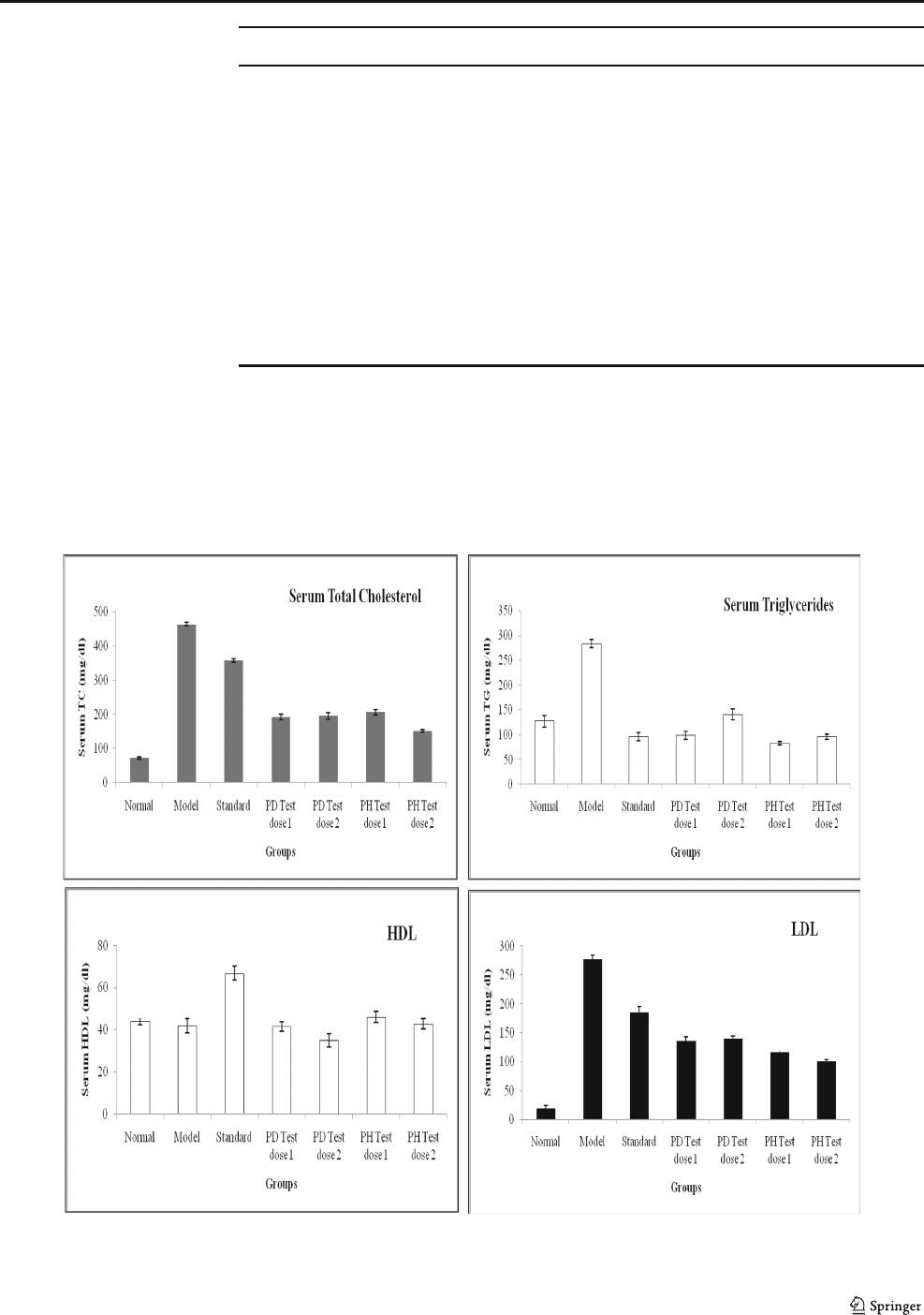

Serum Total Cholesterol (TC)

Blood serum total cholesterol (TC) levels in the seven groups

are shown in Fig. 1. Before the experiment, TC showed no

significant difference among groups. High-cholesterol diet

could significantly increase serum TC levels (462.74 ± 5.62

vs. 72.17 ± 3.2 mg/dl) in group B (Model) compared to group

A (Normal). Group C (Standard) administrated with atorva-

statin averted the rise in cholesterol levels by bringing 22.95%

reduction as compare to group B (Model).

Probiotic test solution (Groups D, E, F and G) showed

varying degrees of cholesterol lowering abilities in vivo. At

the end of 4 weeks, compared with the group B (Model), both

the strains showed significant (p < 0.05) reduction in serum

TC levels as 58.58, 57.74, 55.6, and 67.21% in Groups D, E,

F, and G, respectively. Thus, groups D, E, and F (PD Test dose

1, 2 and PH dose 1) showed comparable effect on cholesterol

reduction, while group G exhibited maximum total cholesterol

lowering potential (151.77 mg/dl vs. 462.74 mg/dl of model).

In a study of Mohania et al. [11] concerning lipid profile by

feeding LaVK2 Dahi on hypercholesterolemic rats, plasma

total cholesterol level was decreased by 22.6% when com-

pared to rats fed with buffalo milk.

Serum Triglycerides (TG)

High-fat diet administered group B (Model) showed signifi-

cant ( p < 0.05) rise in serum triglyceride levels, 122.3 5%

compared to group A (Normal). Treatment with standard

and potential probiotics significantly reduced the triglyceride

levels, 66.3%, 65.26%, 50.5%, 70.69%, and 66.21%, respec-

tively, in groups C, D, E, F, and G; compared to group B

(Model) as depicted in Fig. 1. There were no significant dif-

ferences (p > 0.05) among groups C (Standard), D (PD test

dose 1) F (PH test dose 1), and G (PH test dose 2) as they

showed nearly similar effects on serum triglyceride level of

rats. Thus, based on the results we can assume, probiotics

might be able to lower serum triglyceride level akin to stan-

dard cholesterol lowering drugs available in the market (i.e.,

atorvastatin).

Table 2 Anthropogenic

parameters of rats during 28 day

Groups Weight gain (g) Food consumption (g/day) Food efficiency % Fat pad (g)

A 20.58 ± 2.86

d

100.57 ± 10.29

a

20.66 ± 2.95

e

2.97 ± 1.17

b

B45.48±7.5

a

80.39 ± 4.16

c

56.47 ± 12.74

a

3.42 ± 0.45

a

C 14.02 ± 3.46

e

79.51 ± 4.17

c

17.89 ± 1.16

f

2.84 ± 0.71

b

D 30.65 ± 2.71

b

87.69 ± 3.84

b

34.96 ± 3.44

b

2.06 ± 0.30

e

E 26.77 ± 1.19

c

86.19 ± 3.36

b

31.50 ± 1.19

c

2.70 ± 0.38

c

F 24.74 ± 6.72

c

86.82 ± 4.44

b

28.48 ± 4.56

d

2.34 ± 0.41

d

G 29.69 ± 4.69

b

86.48 ± 3.49

b

34.38 ± 7.52

b

2.92 ± 0.48

b

Values are expressed as Mean ± S.E.M; *Values with different superscripts differ

significantly (p < 0.05) in each columns

Table 3 Effect of probiotic PD2

and PH5 on weight of visceral

organs of rats

Groups Liver Kidney Spleen Lungs Heart

A 6.95 ± 0.22 0.93 ± 0.05 0.5 ± 0.04 1.54 ± 0.08 0.86 ± 0.07

B 11.23 ± 0.54# 0.98 ± 0.09 0.8 ± 0.06# 1.6 ± 0.11 0.91 ± 0.04

C 10.73 ± 0.04 0.86 ± 0.02 0.68 ± 0.03 1.66 ± 0.14 0.9 ± 0.07

D 8.03 ± 1.96* 0.83 ± 0.17 0.58 ± 0.12 1.25 ± 0.26 0.7 ± 0.14

E 10.72 ± 0.48 1 ± 0.10 0.9 ± 0.08 1.61 ± 0.18 0.85 ± 0.08

F 9.88 ± 0.63 0.78 ± 0.03 0.76 ± 0.07 1.2 ± 0.04 0.83 ± 0.08

G 10.7 ± 0.08 0.81 ± 0.04 0.7 ± 0.07 1.53 ± 0.02 0.9 ± 0.03

Values expressed are Mean ± S.E.M; * – significantly different from model (B); # – significantly different from

normal (A)

Probiotics & Antimicro. Prot.

Batish et al. [12] r eported 23.26% and 21.09% reduc-

tion in serum TC and TG, respectively, while evaluating

potential of probiotic strains in SD (Sprague-Dawley)

rats. Further, Singhora et al. [13] reported 20.69% re-

duction in serum TG level by feeding fermented milk

with Lact. gasseri Lg70.

Table 4 Serum lipid profile (mg/

dl) of rats at the end of feeding

period

Groups Total cholesterol Triglycerides HDL-C LDL-C

A 72.17 ± 3.20

e

127.27 ± 11.55

b

43.92 ± 1.44

b

19.8 ± 4.09

f

B 462.74 ± 5.62

a

283.37 ± 7.71

a

41.95 ± 3.32

b

276.74 ± 7.42

a

C 356.57 ± 5.83

b

95.5 ± 7.89

c

66.74 ± 3.33

a

184.76 ± 9.91

b

D 191.67 ± 9.16

c

98.47 ± 7.44

c

41.42 ± 2.35

b

135.42 ± 7.72

c

E 195.59 ± 9.36

c

140.27 ± 11.24

b

34.96 ± 3.17

c

139.14 ± 4.87

c

F 205.47 ± 7.41

c

83.06 ± 3.9

c

45.95 ± 2.64

b

116.36 ± 6.34

d

G 151.77 ± 4.06

d

95.8 ± 5.34

c

42.71 ± 2.60

b

101.72 ± 2.41

e

Anova table

S.E.M. 4.77 5.86 1.96 4.63

F-Test * * * *

CD 14.48 17.78 5.94 14.04

%CV 3.54 7.69 7.48 5.76

Values expressed are Mean ± S.E.M; *Values with different superscripts differ significantly (p < 0.05) in each

rows and columns

b

a

c

b

c

c

c

b

a

b

b

c

b

b

a

e

b

d

c

c

c

e

a

b

c

c

c

d

Fig 1 Effect of probiotic on (i) Serum total cholesterol (TC) level; (ii) Serum triglyceride (TG) level; (iii) HDL-C level; and (iv) LDL-C level. *Values

with different superscripts differ significantly (p < 0.05)

Probiotics & Antimicro. Prot.

High-Density Lipoproteins (HDL-C)

High-density lipoprotein accumulates surplus cholesterol that

cholesterol metabolizing cells cannot utilize. Thus, it’sanim-

portant factor to control arteriosclerosis. Atorvastatin admin-

istered in the group C (Standard) raised the HDL level in

serum by 51.95% (highest compared to each group) compared

to group B (Model). Moreover, group B (Model) showed

4.49% reduction (p > 0.05) when compared with group A

(Normal). Furthermore, three groups, D, F, and G, exhibited

(p > 0.05) no effect compare to group B (Model). Whereas,

group E fed with LACT. fermentum PD2 showed significant

decrease compared to Model and other probiotics (Fig. 1).

Thus, treatment with probiotic did not show obvious influ-

ences on HDL levels in this study.

Similarly, Tamai et al. [14], Ibrahim et al. [15] and St-Onge

et al. [16] did not observe any variation in the level of blood

HDL cholesterol in rats or human by feeding fermented milk,

milk yogurt, and soy yogurt. Lact. plantarum MA2 isolated

from Tibetan kefir grains did not influence serum HDL level

in rats [17].

Low Density Lipoproteins (LDL-C)

LDL-C is the main component of serum cholesterol inducing

hypercholesterolemia. The elevated serum LDL cholesterol

levels induced by feeding high-cholesterol diets were reduced

in the PD2 and PH5 strains treated groups. Atorvastatin

showed significant reduction (p < 0.05) 33.24% (184.76 ±

9.91 vs. 276.74 ± 7.42) in LDL level as compared to group

B (Model). Potential probiotics (treatment groups D, E, F, and

G) demonstrated significant (p < 0.05) decline in the LDL

levels, 51.07%, 49.73%, 57.96%, and 63.25%, respectively,

as compared to the group B (Model). As shown in Fig. 1,we

can postulate that both PD Test dose 1 and 2 treated groups (D

and E) exhibited comparable effect in LDL reduction 135.42

and 139.14 mg/dl, respectively. PH Test dose 1 (Group F)

significantly diminished LDL (116.36 mg/dl vs. 276.74 of

Model). Among all probiotic fed groups, PH Test dose 1

(Group G) was able to reduce maximum LDL (101.72 mg/

dl) compared to group B (Model) 176.74 mg/dl.

Similarly, supplementation of diet with Lact. plantarum

LP91 and LP21 resulted in significant reduction in LDL-C

values by 38.13 and 21.42%, respectively [12]. In a recent

study by Singhora et al. [13], test group which was fed on

milk fermented with Lact. gasseri Lg70, a 49.54% significant

reduction in LDL-C was observed compare to positive control

(HD diet) group.

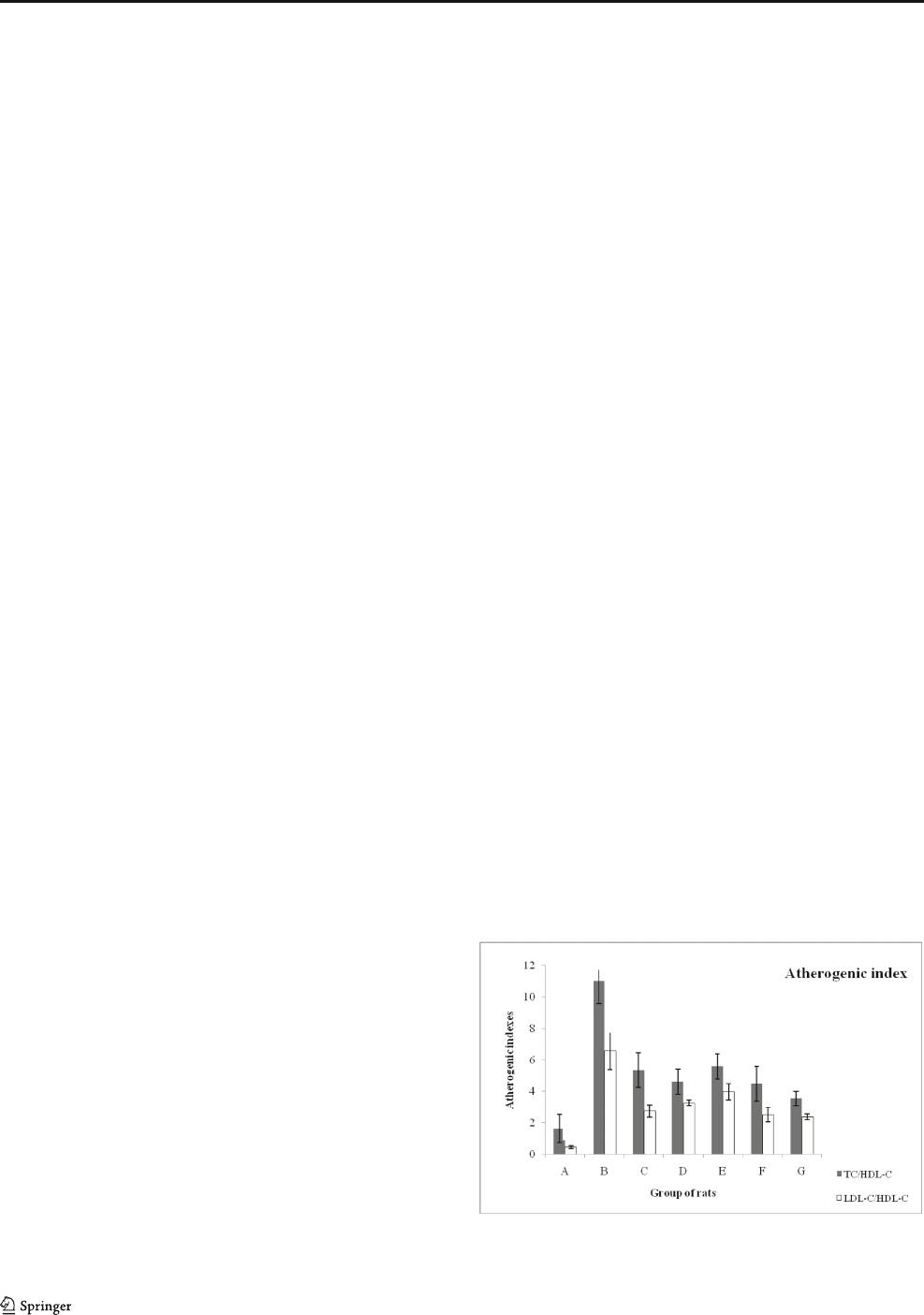

Atherogenic Index

TC/HDL-C and LDL-C/HDL-C ratios are recognized as two

important signs of CVDs risk and were reduced in rats

supplemented with LAB [1, 18]. The higher ratios are, the

greater the CVD risk is. Therefore, reduction in serum TC,

LDL-C, and increase in HDL-C may be an imperative treat-

ment alternative for CVDs.

In the present study, as shown in Fig. 2, AI of the group B

(Model) showed sharp increase after 4 weeks of feeding on the

hyperlipidemic diet in comparison with that of group A

(Normal control). All the four groups fed with probiotic dahi

(D, E, F and G) including group C (Standard) exhibited sig-

nificantly lower TC/HDL-C and LDL-C/HDL-C ratios when

compared with hypercholesterolemic control group (Model)

proposed their potentiality in cholesterol metabolism. Among

all probiotic fed groups, Lact. fermentum PH5 fed groups (F

and G) exhibited maximum potential to bring down athero-

genic index by affecting TC/HDL-C and LDL-C/HDL-C ra-

tios compared to PD2 fed groups (E and F). PH5 Test dose 2

has significantly high ability to reduce TC/HDL-C (3.58 vs.

11.18) and LDL-C/HDL-C (2.35 vs. 6.59). Batish et al. [12]

also reported that AI for the probiotic (Lact. plantarum)treat-

ment groups [HD91 (2.41) and HD21 (3.10)] decreased sig-

nificantly when compared with the hypercholesterolemic con-

trol group (4.24).

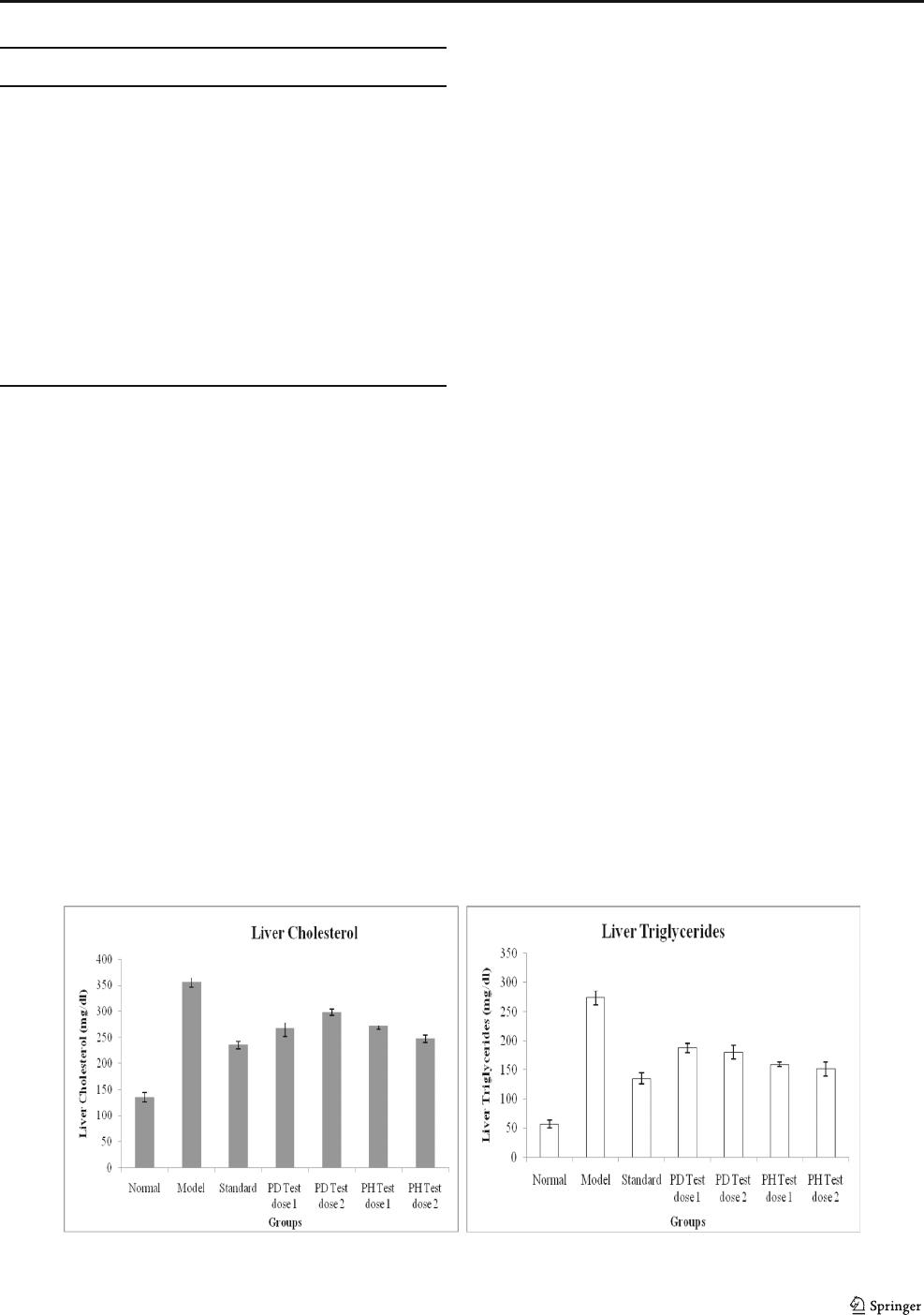

Effect of potential Probiotic feeding on Liver lipid

profile

Liver total cholesterol (Liver TC)

Liver TC (Table 5) levels differed significantly among all the

seven groups. The liver TC levels of rats fed a high-

cholesterol diet group B (Model) had significantly increased

(p < 0.05) compared to 163.39% with group A (Normal).

Standard drug atorvastatin prevented the rise in liver choles-

terol levels with reduction of 33.88% (235.4 ± 7.72 vs. 356 ±

9.73) as oppose to the group B (Model).

PD test dose 1 and 2 (Group D and E) administration re-

sulted in decreasing the liver cholesterol level (p <0.05)by

24.97 and 16.34%, respectively. PH Test dose 1 (Group F)

F

f

E

e

D

D

d

D

B

b

C

d

c

A

a

Fig 2 Effect of probiotic on atherogenic index. *Values with different

superscripts differ significantly (p < 0.05)

Probiotics & Antimicro. Prot.

showed comparable effect with PD Test dose 1 (Group D) as

shown in Fig. 3. While, Group C (Standard) treated with ator-

vastatin and PH Test dose 2 (Group G) showed maximum

besides comparable potential to diminish liver cholesterol in

rats. Similarly, fermented dairy product isolate NS12 (Lact.

delbrueckii sp. bulgaricus) was reported effective to reduce

34.58% liver cholesterol [8]. The effect of dietary treatments

(probiotic curd) on liver lipid profile (serum total cholesterol,

triglycerides) has been recorded in Table 5.

Liver Triglycerides (Liver TG)

The group A (Normal) displayed the lowest liver TG level and

Model group (B) displayed the highest liver TG level.

Atorvastatin treatment resulted in significant decline of

50.58% in the liver triglycerides value compared to group B

(Model). All the four experimental groups (HC + PD2) and

(HC + PH5) had lower levels of liver TG than HC group (p <

0.05), and there was no obvious differences among the four

groups. All four experimental groups D, E, F, and G, fed with

probiotic dahi, showed decrease in liver triglyceride values

31.57, 34.31, 41.82, and 44.96%, respectively, as shown in

Fig. 3. Group C (Standard), and probiotic Lact. fermentum

PH5 Test dose 2-treated group G demonstrated comparable

results in terms of liver triglyceride reduction. The lower level

of hepatic cholesterol and triglyceride content could reduce

the rate of conversion of LDL to LDL-C particles, and result

in the decline in serum LDL-C concentration, that might be

another reason for the effects of our two strains to lower LDL-

Clevel.

Supplementation with either of the two strains was effec-

tive in reducing serum TC, LDL-C, and TG concentrations in

rats compared to those fed the same high-cholesterol diet but

without L AB supplement at ion. In particular, these effe ct s

were more evident with Lact. fermentum PH5 fed groups.

Our results confirm those described in previous reports [1, 8,

11, 12, 19].

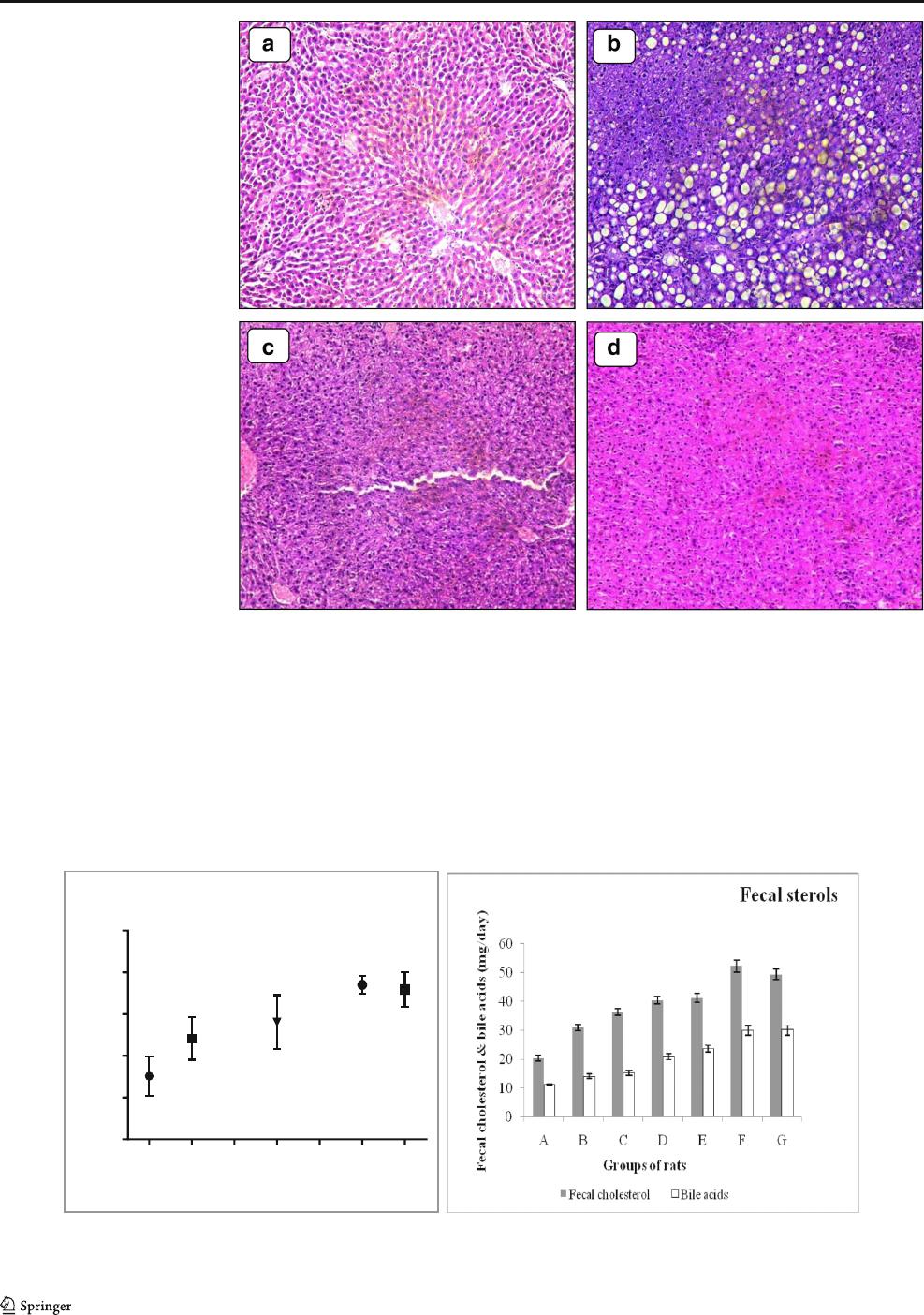

Histopathology Analysis

Fig. 4 illustrated the effects of Lact. fermentum strains PD2

and PH5 on hepatic steatosis. Hematoxylin-eosin (HE) stain-

ing, a semi-quantitative method showed the differences in

liver tissue structures and lipid accumulation of all groups.

The rat liver of group A (Normal) had a well-organized

structure as there was no fatty vacuolization in liver cells.

The liver tissue in the group B (Model) had a moderate degree

of vacuolization and increased lipid deposition in the cyto-

plasm. Hepatocyte steatosis was obviously alleviated by feed-

ing probiotic dahi containing PD2 and PH5 strains compare to

group B (Model). The LAB-treated rats exhibited overall nor-

mal gross liver appearances but high fatty vacuolization in

Model group. Similarly, liver lipid deposition was evaluated

in a semi quantitative manner by Xie et al. [2].

Table 5 Liver lipid profile (mg/dl) of rats at the end of feeding period

Groups Liver TC Liver TG

A 135.16 ± 8.86

e

56.71 ± 7.08

d

B 356.00 ± 9.73

a

274.07 ± 12.16

a

C 235.40 ± 7.72

d

135.46 ± 9.5

c

D 267.12 ± 15.49

c

187.55 ± 8.3

b

E 297.85 ± 6.25

b

180.04 ± 11.94

b

F 273.10 ± 8.01

c

159.48 ± 3.77

bc

G 246.90 ± 7.44

d

150.86 ± 11.58

c

Anova table

S.E.M. 6.72 6.81

F-Test * *

CD 20.38 20.65

%CV 4.50 7.21

Values expressed are Mean ± S.E.M; *Values with different superscripts

differ significantly (p < 0.05) in each column

a

e

c

d

c

b

c

c

a

d

c

b

b

bc

Fig. 3 Effect of probiotic on (i) Liver-TC level, and (ii) Liver-TG level. *Values with different superscripts differ significantly (p < 0.05)

Probiotics & Antimicro. Prot.

Fecal Sterol Analysis

Many probiotic strains could augment fecal elimination of bile

acids through bile acid deconjugation, and this may alter the

cholesterol synthesis pathways and resulted in a decrease of

serum cholesterol concentration [20 ]. We found more bile

acids released in the feces as well as highest fecal cholesterol

especially in those rats fed with PH5 groups (F and G).

PH5 Test dose 1 released highest fecal cholesterol (52.26

mg/day) among other probiotic fed groups (D, E, and F) as

well as group C (Standard). Moreover, both PH5-treated

groups (F and G) liberated highest bile acid in the feces of rats

30.05 and 30.43 mg/day, respectively followed by group E

(23.39 mg/day) and group D (20.18 mg/day). The lower fecal

cholesterol and bile acids in the feces of rats of group B

(Model) might be due to deposition or absorption of lipids in

Fig 4 Histopathology of liver A:

group A (Normal diet); B: group

B (Model group-high cholesterol

diet); C: High-cholesterol diet +

PD2 probiotic dahi; D: High-

cholesterol diet + PH5 probiotic

dahi

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

30

40

50

60

70

80

Fecal water content

Groups

%Fecal Water

c

b

a

b

ab

a

a

d

e

F

f

E

C

D

cb

C

B

A

a

a

Fig 5 (i) Analysis of fecal water content, (ii) Effect of probiotic on fecal cholesterol and bile acid (4th week). *Values with different superscripts differ

significantly (p < 0.05)

Probiotics & Antimicro. Prot.

tissuesaswellasblood(Fig.5). Overall, Lact. fermentum PH5

seems to be more effective in fecal cholesterol reduction and

liberation of free bile acids through effective bile deconjugation

mechanism. Similar experiment was performed by Xie et al. [2]

using Lact. fermentum M1-16 feeding in hyperlipidemic rats;

and reported 30.2% (37. 33 mg/day) fecal cholesterol with 19%

(19.29 mg/day) fecal cholic acid. Similar observation was report-

ed by Batish et al. [12] as fecal cholic acid excretion increased

throughout the experimental period in the probiotic treatment

groups HDCap91, HD91 and HD21.

Fecal Water Content Analysis

Since the fecal water content can be exploited as an index of

fecal elimination, our observations recommend that these two

LAB strains have laxative potential and may stimulate bowel

movements. As a result, the transit time for cholesterol absorp-

tion in the intestine might also be reduced.

Fecal water content data collected at the forth week is

shown in Fig. 5. However, at the end of the feeding period,

highest fecal moisture content was found in Lact. fermentum

PH5 fed groups (F and G) as 67.01 and 65.88, respectively (p

< 0.05). The results were comparable (p > 0.05) with group C

(Standard) who demonstrated 62.1% moisture content in the

feces of rats. PD2 Test dose 2 also exhibited 59.72 percent

moisture in feces of rats. In a similar study by Xie et al. [2],

probiotic solutions having Lact. plantarum 9-41-A and Lact.

fermentum M1-16 exhibited 63% and 62% fecal moisture

content, respectively, compare to their Model (53%).

Fecal Microbiological Analysis

Intestinal microbiota plays an important role in modulation of

host energy and lipid metabolism [21]. The effects of probiotic

lactobacilli on different bacterial counts in feces had been

investigated previously by different research groups [22, 23].

The overall mean fecal bacteria counts at 0 and 28 days ob-

tained from different experimental groups are recorded in

Table 6 revealed the effects of the different diets and LAB

supplementation on the rat intestinal bacterial flora.

The rats fed on Lactobacillus strains as a dietary adjunct

maintained a high level of lactobacilli (probiotic Lact. fermentum

PD2 and PH5) in the fecal samples throughout the experimental

period compared with the control groups. Total lactobacilli

rangedfrom8.47to9.94CFU/goffecesinalltheexperimental

groups. We also found Coliforms were significantly increased in

high-cholesterol diets fed rats, and PD2 and PH5 strains restored

the changes. Total coliforms count ranged from 6.03 to 7.24

CFU/g among all the treatment groups. Thus, increase in the

number of fecal lactobacilli indicates their effective colonization

in rat intestinal tract besides decrease in coliforms. However , rats

supplemented with the diet containing PH dose 1 and 2 (Groups

F and G) showed a marginal decrease in fecal E. coli counts

compared with their counts on 0 day. Comparable fecal bacterial

countswereobtainedbyBatishetal.[12] while studying hyper-

cholesterolemia i n SD rats using BSH producing La ct.

plantarum.Huetal.[8] reported relatively similar data while

studying lipid metabolism in Lactobacillus strains, i.e., NS5

and NS12.

Conclusion

Present study demonstrated that animals fed with probiotic dahi

(i.e., fermented with potential probiotic strains PD2 and PH5)

might be useful in reducing hypercholesterolemia induced by

the consumption of the atherogenic diet. At the outset, the pro-

biotic dahi reduced plasma cholesterol and triglycerides suggest-

ing that the effects of the probiotic dahi might have commenced

at the level of the GI tract, inhibiting absorption of these lipids. In

addition to reducing hepatic cholesterol and hepatic triglyceride s,

aortic tissue lipids were also decreased by ingestion o f the probi-

otic dahi. Furthermore, the indigenous strains have also shown to

possess bile salt hydrolase (BSH) activity in vitro and thereby

suggesting that this BSH activity could be responsible for low-

ering the plasma total cholesterol concentra tion. Our study had

some limitations , we us ed W istar rats, and the effe cts observed in

animal model may not be exactly the same in human. However,

well-designed placebo-con trolled clinical trials need to be con-

ducted to validate the ef ficacy and safety of the strain and its use

in the management of high cholesterol in humans.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of

interest.

Table 6 Effects of probiotic feeding on fecal bacterial population

Treatment groups Days Lactobacilli Coliforms E. coli

A (Normal) 0 8.47 ± 0.15 6.93 ± 0.05 7.14 ± 0.14

28 8.95 ± 0.13 6.68 ± 0.08 7.09 ± 0.21

B (Model) 0 8.97 ± 0.03 7.08 ± 0.09 7.74 ± 0.13

28 8.76 ± 0.12 7.23 ± 0.12 7.82 ± 0.16

C (Standard) 0 8.81 ± 0.13 7.24 ± 0.08 7.76 ± 0.07

28 9.03 ± 0.24 7.08 ± 0.03 7.56 ± 0.11

D (PD test dose 1) 0 9.29 ± 0.03 6.26 ± 0.13 7.75 ± 0.17

28 9.94 ± 0.78 6.12 ± 0.02 7.66 ± 0.21

E (PD test dose 2) 0 9.50 ± 0.15 6.10 ± 0.05 7.56 ± 0.05

28 9.84 ± 0.27 6.04 ± 0.13 7.23 ± 0.13

F (PH test dose 1) 0 9.06 ± 0.04 6.63 ± 0.15 7.48 ± 0.08

28 9.86 ± 0.09 6.07 ± 0.19 6.89 ± 0.11

G (PH test dose 2) 0 9.20 ± 0.10 6.19 ± 0.07 7.77 ± 0.12

28 9.45 ± 0.06 6.03 ± 0.04 6.57 ± 0.19

*Values expressed are Mean ± S.E.M

Probiotics & Antimicro. Prot.

Ethical Appro val This work was approved by Institutional Animal

Ethical Committee (IAEC) of Anand Pharmacy College, Anand,

Gujarat, India (Protocol No: APC/2015-IAEC/1504).

References

1. Aminlari L, Shekarforoush SS, Hosseinzadeh S, Nazifi S,

Sajedianfard J, Eskandari MH (2018) Effect of probiotics Bacillus

coagulans and Lactobacillus plantarum on lipid profile and feces

bacteria of rats fed cholesterol-enriched diet. Probiotics Antimicrob

Proteins 27:1–9

2. Xie N, Cui Y, Yin YN, Zhao X, Yang JW, Wang ZG, Fu N, Tang Y,

Wang XH, Liu XW, Wang CL (2011) Effects of two Lactobacillus

strains on lipid metabolism and intestinal microflora in rats fed a

high-cholesterol diet. BMC Complement Altern Med 11(1):53

3. Ashar MN, Prajapati JB (2001) Role of probiotic cultures and

fermented milks in combating blood cholesterol. Indian J

Microbiol 41:75–86

4. Thakkar PN (2016) Screening, characterization and probiotic sig-

nificance of indigenous bacterial isolates. Doctoral dissertation the-

sis submitted to Department of Life Sciences, University School of

Sciences, Gujarat University, Ahmedabad, Gujarat State, India

5. Thakkar P, Modi H, Prajapati J (2015) Isolation, characterization

and safety assessment of lactic acid bacterial isolates from

fermented food products. Int J Curr Microbiol App Sci 4(4):713–

725

6. Thakkar P, Modi H, Dabhi B, Prajapati J (2014) Bile tolerance, bile

deconjugation and cholesterol reducing properties of Lactobacillus

strains isolated from traditional fermented foods. Int J Fermented

Foods 3(2):157–165

7. Shakuto S, Oshima K, Tsuchiya E (2005) Glimepiride exhibits

prophylactic effect on atherosclerosis in cholesterol-fed rabbits.

Atherosclerosis 182(2):209–217

8. Hu X, Wang T, Li W, Jin F, Wang L (2013) Effects of NS

Lactobacillus strains on lipid metabolism of rats fed a high choles-

terol diet. Lipids Health Dis 12:67–78

9. Lee DK, Jang S, Baek EH, Kim MJ, Lee KS, Shin HS, Chung MJ,

Kim JE, Lee KO, Ha NJ (2009) Lactic acid bacteria affect serum

cholesterol levels, harmful fecal enzyme activity, and fecal water

content. Lipids Health Dis 8:21–29

10. Vijayendra SVN, Gupta RC (2012) Assessment of probiotic and

sensory properties of dahi and yogurt prepared using bulk-freeze

dried cultures in buffalo milk. Ann Microbiol 62:939–947

11. Mohania D, Kansal VK, Shah D, Na gpal R, Kumar M (2014)

Therapeutic effect of probiotic dahi on plasma, aortic and hepatic

lipid profile of hypercholesterolemic rats. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol

Ther 18:490–497

12. Batish VK, Kumar R, Grover S (2010) Hypocholesterolemic effect

of dietary inclusion of two putative probiotic bile salt hydrolase-

producing Lactobacillus plantarum strains in Sprague-Dawley rats.

Br J Nutr 105:561–572

13. Singhora G, Neha P, Ravinder KM, Santosh KM (2014)

Hypocholesterolemic effect of a Lactobacillus gasseri strain

Lg70 isolated from breast fed human infant feces. J Inno Biol

1(2):105–111

14. Tamai Y, Yoshmitsu N, Watanabe Y, Kuwabara Y, Nagai S (1996)

Effect of milk fermented by culturing with various of lactic acid

bacteria and yeast on serum cholesterol level in rats. J Ferment

Bioeng 82:181–182

15. Ibrahim A, El-sayed E, El-zeini H (2005) The hypocholesterolemic

effect of milk yogurt and soy-yogurt containing bifidobacteria in

rats fed on a cholesterol-enriched diet. Int Dairy J 15:37–44

16. St-Onge MP, Farnworth ER, Savard T, Chabot D, Mafu A, Jones PJ

(2002) Kefir consumption does not alter plasma lipid levels or cho-

lesterol fractional synthesis rates relative to milk in hyperlipidemic

men: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Complement Altern Med

2:1–7

17. Wang Y, Xu NV, Xi A, Ahmed Z, Zhang B, Bai X (2009) Effects of

Lactobacillus plantarum MA2 isolated from Tibet kefir on lipid

metabolism and intestinal microflora of rats fed on high-

cholesterol diet. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 84:341–347

18. Lampka M, Grąbczewska Z, Jendryczka-Maćkiewicz E, Hoł

yńska-

Iwan I, Sukiennik A, Kubica J, Halota W, Tyrakowski T (2010)

Circulating endothelial cells in coronary artery disease. Pol Heart

J 68(10):1100–1105

19. Nguyen T, Kang JH, Lee MS (2007) Characterization of

Lactobacillus plantarum PH04, a potential probiotic bacterium

with cholesterol-lowering effects. Int J Food Microbiol 113:358–

361

20. Park YH, Kim JG, Shin YW, Kim SH, Whang KY (2007) Effect of

dietary inclusion of Lactobacillus acidophilus ATCC 43121 on

cholesterol metabolism in rats. J Microbiol Biotechnol 17(4):655–

662

21. Velagapudi VR, Hezaveh R, Reigstad CS, Gopalacharyulu P,

Yetukuri L, Islam S, Felin J, Perkins R, Borén J, Orešič M,

Bäckhed F (2010) The gut microbiota modulates host energy and

lipid metabolism in mice. J Lipid Res 51(5):1101–1112

22. Usman HA (2000) Effect of administration of Lactobacillus gasseri

on serum lipids and fecal steroids in hypercholesterolemic rats. J

Dairy Sci 83:1705–1711

23. Liong MT , Shah NP (2006) Effects of Lactobacillus casei symbi-

otic on serum lipoprotein, intestinal microflora and organic acids in

rats. J Dairy Sci 89:1390–1399

Publisher’sNoteSpringer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdic-

tional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Probiotics & Antimicro. Prot.