RES E AR C H Open Access

DNA methylation signature in blood

mirrors successful weight-loss during

lifestyle interventions: the CENTRAL trial

Maria Keller

1,2,3†

, Anat Yaskolka Meir

4†

, Stephan H. Bernhart

5,6,7

, Yftach Gepner

4,8

, Ilan Shelef

9

, Dan Schwarzfuchs

9,10

,

Gal Tsaban

4

, Hila Zelicha

4

, Lydia Hopp

5

, Luise Müller

2,3

, Kerstin Rohde

1,2

, Yvonne Böttcher

3,11,12

,

Peter F. Stadler

6,13,14,15,16,17,18

, Michael Stumvoll

1,2,3,19

, Matthias Blüher

1,2

, Peter Kovacs

2*

and Iris Shai

4*

Abstract

Background: One of the major challenges in obesity treatment is to explain the high variability in the individual’s

response to specific dietary and physical activity interventi ons. With this study, we tested the hypothesis that

specific DNA methylation changes reflect individual responsiveness to lifestyle intervention and may serve as

epigenetic predictors for a successful weight-loss.

Methods: We conducted an explorative genome-wide DNA methylation analysis in blood samples from 120

subjects (90% men, mean ± SD age = 49 ± 9 years, body mass-index (BMI) = 30.2 ± 3.3 kg/m

2

) from the 18-month

CENTRAL randomized controlled trial who underwent either Mediterranean/low-carbohydrate or low-fat diet with

or without physical activity.

Results: Analyses comparing male subjects with the most prominent body weight-loss (responders, mean weight

change − 16%) vs. non-responders (+ 2.4%) (N = 10 each) revealed significant variation in DNA methylation of

several genes including LRRC27, CRISP2, and SLFN12 (all adj. P <1×10

−5

). Gene ontology analysis indicated that

biological processes such as cell adhesion and molecular functions such as calcium ion binding could have an

important role in determining the success of interventional therapies in obesity. Epigenome-wide association for

relative weight-loss (%) identified 15 CpGs being negatively correlated with weight change after intervention (all

combined P <1×10

− 4

) including new and also known obesity candidates such as NUDT3 and NCOR2. A baseline

DNA methylation score better predicted successful weight-loss [area under the curve (AUC) receiver operating

characteristic (ROC) = 0.95–1.0] than predictors such as age and BMI (AUC ROC = 0.56).

Conclusions: Body weight-loss following 18-month lifestyle intervention is associated with specific methylation

signatures. Moreover, methylation differences in the identified genes could serve as prognostic biomarkers to

predict a successful weight-loss therapy and thus contribute to advances in patient-tailored obesity treatment.

Keywords: Lifestyle intervention, Weight-loss, Epigenetics, DNA methylation, Gene

© The Author(s). 2020 Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License,

which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give

appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if

changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons

licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons

licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain

permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the

data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

†

Maria Keller and Anat Yaskolka Meir contributed equally to this work.

2

Medical Department III – Endocrinology, Nephrology, Rheumatology,

University of Leipzig Medical Center, 04103 Leipzig, Germany

4

Faculty of Health Sciences, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, P.O.Box 653,

84105 Beer Sheva, Israel

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article

Keller et al. Genome Medicine (2020) 12:97

https://doi.org/10.1186/s13073-020-00794-7

Background

Obesity represents a major health burden worldwide

[1]. Increasing energy expenditure and limiting caloric

intake are the major set points to control obesity;

however, only restricted long-term success could be

reached so fa r, potentially caused by hormonal, meta-

bolic, and neurochemical adaptations that stabilize

weight-l oss and may lead to weight regain [2]. The

majority of individuals who experience weight-loss

will regain it over time [3 , 4]. Thus, the effective

long-term treatment of obesity would require a sys-

tematic assessment a nd understanding of genetic, epi-

genetic, and lifestyle fac tors that potentially affect

energy intake, metabolism, and energy expenditure.

Therefore, a better understanding of this highly com-

plex interaction is required to explain the high vari-

ability in the individual’s response to specific dietary

and physical activity (PA) inte rventions. This would

allow to develop more successful preventive and

therapeutic strategies ultimately leading to personal-

ized lifestyle treatments in the battle against obesity

[5, 6].

Whereas poor adherence to different lifestyle inter-

ventions represents a strong factor in response to

weight-l oss ther api es [7], emerging evidence implies

that genetic and epigenetic predictors play a role in

inter-individual variability of metabolic response [8].

Further, this individual response in weight regain is

mainly driven by a n unadjusted energy intake after

the intervention [9], since after successful we ight-loss

less caloric intake is required to maintain the

achieved weight. Several recent findings directly link

obesity development to DNA methylation changes in

related target tissues such as adipose tissue (AT) [10,

11], ske letal muscle [12–14], and also in blood [15–

18]. DNA methylation marks in whole blood samples

have been repo rted to correlate with target tissue

changes [17] and would thereby represent an easy ac-

cessible proxy for the future development of personal-

ized treatment strategies and prediction of

therapeutical success. However, DNA methylation

changes upon long-term behavioral interventions (e.g.,

specific diets, exercise) are scarcely investigated so far.

In the present study, we conducted a genome-wide

DNA methylation analysis in blood samp les from 120

subjects who underwent the 18-month randomized con-

trolled trial (RCT) CENTRAL [ 19 ]. The CENTRAL trial

has been conducted under strict monitoring conditions

in the Dimona Nuclear Research Center, Negev, located

in a desert in Israel, thus providing an almost

homogenous environment and a low drop off rate. In

this exploratory study, we tested the hypotheses that (i)

metabolic changes mediated by different types of lifestyle

intervention including diet and PA (Mediterranean low-

carb (MED/LC) vs. low-fat (LF) vs. MED/LC + PA vs.

LF + PA) correlate with variation in DNA methylation

and (ii) that specific DNA meth ylation signatures reflect

individual responsiveness to lifestyle intervention to

serve as epigenetic predictors for successful weight-loss.

Methods

Study population and design

The CENTRAL RCT was conducted between 2012 and

2014 in an isolated nuclear research center workplace in

Israel and primarily aimed to assess changes on visceral

fat depots after diet and exercise interventions. The cen-

ter provides a sophisticated infras tructure including an

internal clinic, a cafeteria, and a designated space for

lifestyle and PA sessions, thus allowing this well-

structured and precisely controlled lifestyle intervention

trial. Two hundred seventy-eight of the participants with

a mean age of 48 years and a mean body mass index

(BMI) of 30.8 kg/m

2

fulfilled the pre-specified inclusion

criteria for the trial. Inclusion criteria for the exploratory

analyses were, first, either abdominal obesity (waist cir-

cumference (WC) > 102 cm for men and > 88 cm for

women) or dyslipidemia (serum triglycerides > 150 mg/

dL and high-density -lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) <

40 mg/dL for men and < 50 mg/dL for women); secon d,

the provision of signed and dated informed consent

form; and third, the stated willingness to comply with all

study procedures and availability for the duration of the

study. Exclusion criteria included pregnant or lactating

women, subjects with serum creatinine ≥2 mg/dL, with

disturbed liver function (≥ 3-fold level of ALT and AST

enzymes), active cancer, individuals who had any restric-

tions regarding physical activity, were highly physical ac-

tive (> 3 h/week) or were included in other nutritional

trials (https://clinicaltria ls.gov/ct2/show/NCT01530724)

[19, 20].

The study was conducted in accordance with the Dec-

laration of Helsinki, and the protocol for the exploratory

analyses was approved by the Medical Ethics Board and

Institutional Review Board at Soroka University Medical

Center, Be’er Sheva, Israel (0239-11SOR). All partici-

pants provided written informed consent before taking

part in the study.

Subjects were randomly assigned to an either LF or

MED/LC diet (N = 1 39 each). Both dietary interven-

tions w ere equal in calories and maintained over the

entire study period. After 6 months, eac h intervention

arm was re-randomized to a group with moderate,

mostly aerobic (80%) PA (LF + PA; MED/LC + PA) or

without PA (LF-PA; MED/LC-PA) for another year of

intervention. Details about the study e nvironment, in-

terventions, endpoint measurements, and detailed

metabolic phenotyping can be obtained elsewhere [19,

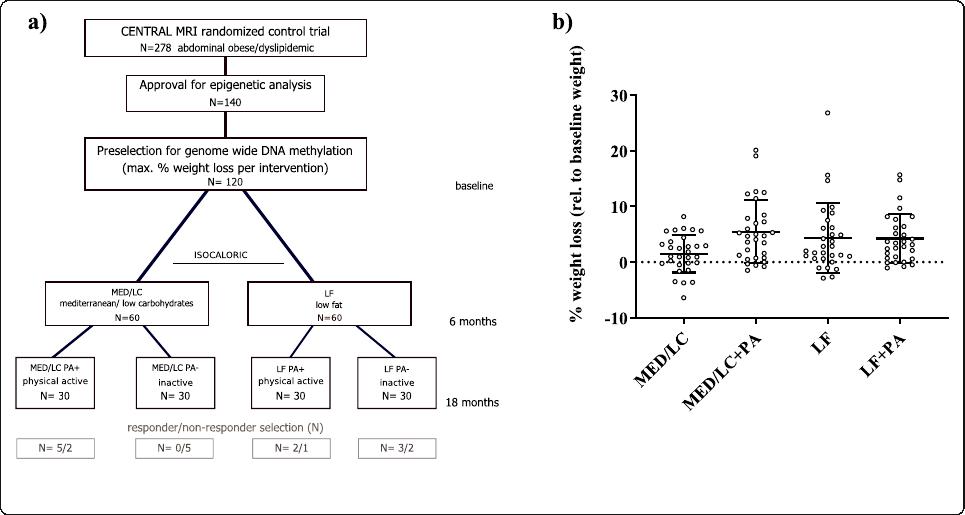

20].TheoverallstudydesignispresentedinFig.1a.

Keller et al. Genome Medicine (2020) 12:97 Page 2 of 18

Sample selection and preparation

Among all CENTRAL participants, a total number of

140 subjects with both baseline and 18 months available

blood samples gave additional consent to genetic ana-

lysis. Out of this subgroup 30 subjects per intervention

group showing the lowest relative weight after 18

months with respect to their initial weight were selected

and included in DNA methylation analysis. Details about

intervention group-specific phenotypes can be found in

Table 1, whereas individual weight-loss (%) is shown in

Fig. 1b.

Blood samples were taken after an overnight fast at

baseline (T0) and at 18 months (T18) after the individ-

uals completed their interventions. Sam ples were stored

at − 80 °C until DNA was extracted following a standard

protocol using proteinase K and 0.2% SDS. Samples were

integrity controlled using gel-electrophoresis and the

concentrations of double-stranded DNA was measured

using Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA (Invitrogen, Thermo-

Fisher Scientific, Germany) and Quantus (Promega,

Germany) technologies.

Genome-wide DNA methylation

Five hundred nanograms of genomic DNA from each

sample was bisulfite converted using EZ DNA Methyla-

tion Gold Kit (Zymo Research, Netherlands). Following

quality control, amplification, and hybridization on Illu-

mina HumanMethylation850 Bead Chips (Illumina, Inc.,

San Diego, CA, USA), the Illumina iScan array scanner

was used to quantify genome-wide DNA methylation

levels at 850 K CpG sites per sample on single-nucleotide

resolution (GenomeScan, Leiden, Netherlands).

Data analysis/statistics

Raw data was first quality controlled using the QC re-

port of the minfi R package [21–23] (Additional file 1).

Beta value densities as well as the control probes were

within predicted specifications. Probes that did not pass

detection P value (P

detect

= 0.01) in more than 1% of all

240 samples were excluded from the analysis. Cross-

reactive probes [24] as well as probes containing known

SNP positions (MASK_snp5_GMAF1p positions from

bioconductor’s Illumin a EPIC manifest [25]) were per se

not excluded from our analysis but are flagged through-

out all result and supplementary tables (Additional file 2).

Prior to all further analysis steps aimed at identifying dif-

ferentially methylated regions (DMRs) and specific CpG

sites (comparison independent), beta values were com-

puted and quantile normalized using minfi R package

([26], pages 9–10) [ 21, 22].

Cell type composition

As dietary interven tions such as western or high-fat diet

have been shown to induce systemic inflammation and

change the immune cell composition in adipose tissue of

mice [27, 28], we analyzed the cell type composition

using the Houseman approach [29] adapted to EPIC ar-

rays by Salas et al. [30]. Possible differences in cell -type

composition were plotted using ggplot2 and analyzed

using Wi lcoxon tests in R. As shown in [26] (pages 4–9),

none of the cell type population changed significantly

Fig. 1 Study design—CENTRAL RCT. a shows the study design of the CENTRAL RCT over the three time points: baseline, 6 months, and 18

months; b shows the weight-loss at 18 months relative to the baseline weight as mean ± SD (%)

Keller et al. Genome Medicine (2020) 12:97 Page 3 of 18

Table 1 Study characteristics of the CENTRAL subgroup selected for genome wide DNA methylation analysis

Trait CENTRAL all (N = 120) P value Low carb (N = 30) Low carb + PA (N = 30) Low fat (N = 30) Low fat + PA (N = 30)

Gender (N; female/male) 10/110 4/26 0/30 5/25 1/29

Age (years)

T

0

49 ± 9.3 47 ± 7.5 50 ± 9.8 50 ± 10.2 48 ± 9.5

Weight (kg)

T

0

90.32 ± 11.5 89.98 ± 14.5 90.58 ± 11.6 87.64 ± 10.4 93.07 ± 8.5

T

18

86.66 ± 11.2 88.50 ± 14.2 85.44 ± 10.8 83.61 ± 9.5 89.11 ± 9.1

Δ

(T18-T0)

− 3.65 ± 5.2 <1×10

−11

− 1.48 ± 3.3* − 5.14 ± 5.6*** − 4.04 ± 6.6** − 3.96 ± 4.2***

BMI (kg/m

2

)

T

0

30.17 ± 3.3 30.09 ± 4.6 30.13 ± 2.4 30.38 ± 3.3 30.08 ± 2.5

T

18

28.97 ± 3.4 29.60 ± 4.4 28.45 ± 2.5 29.02 ± 3.4 28.80 ± 2.8

Δ

(T18-T0)

− 1.20 ± 1.7 <1×10

−11

− 0.49 ± 1.1* − 1.68 ± 1.8*** − 1.36 ± 2.1** − 1.27 ± 1.4***

Waist circumference (cm)

T

0

106.70 ± 8.1 106.56 ± 11.3 108.29 ± 6.7 104.63 ± 7.3 107.56 ± 5.9

T

18

101.98 ± 8.4 103.49 ± 12.0 100.96 ± 7.0 100.50 ± 6.6 102.92 ± 6.7

Δ

(T18-T0)

− 4.81 ± 5.6 <1×10

−14

− 3.07 ± 4.0*** − 7.3 ± 6.2*** − 3.64 ± 6.3** − 5.29 ± 5.1***

HbA1c (%)

T

0

5.59 ± 0.5 5.66 ± 0.6 5.61 ± 0.4 5.60 ± 0.5 5.49 ± 0.4

T

18

5.51 ± 0.5 5.62 ± 0.8 5.47 ± 0.4 5.55 ± 0.5 5.39 ± 0.3

Δ

(T18-T0)

− 0.08 ± 0.3 0.005 − 0.04 ± 0.5 − 0.14 ± 0.2*** − 0.06 ± 0.3 − 0.10 ± 0.2**

Insulin ( μ U/mL)

T

0

18.02 ± 11.3 21.06 ± 15.2 16.85 ± 8.15 17.55 ± 12.1 16.56 ± 8.0

T

18

14.18 ± 7.3 16.66 ± 8.6 13.98 ± 8.1 12.67 ± 6.8 13.50 ± 4.7

Δ

(T18-T0)

− 3.91 ± 7.8 <1×10

−6

− 4.54 ± 10.5* − 3.40 ± 6.24** − 4.66 ± 7.8** − 3.07 ± 6.3*

Visceral adipose tissue area (cm

2

)

T

0

176.19 ± 61.3 162.00 ± 63.6 196.5 ± 63.5 160.60 ± 60.8 185.70 ± 51.3

T

18

128.12 ± 49.8 126.41 ± 47.9 131.33 ± 56.2 121.03 ± 54.3 133.70 ± 41.0

Δ

(T18-T0)

− 48.19 ± 36.2 <1×10

− 27

−35.54 ± 32.7*** − 65.21 ± 38.1*** − 39.73 ± 28.4*** − 52.00 ± 38.6***

Deep subcutaneous adipose

tissue area (cm

2

)

T

0

210.89 ± 70.0 217.50 ± 79.6 210.40 ± 64.8 201.30 ± 66.9 214.30 ± 70.2

T

18

144.71 ± 48.7 152.99 ± 60.2 139.50 ± 41.7 143.39 ± 41.6 142.96 ± 50.5

Δ

(T18-T0)

− 66.66 ± 42.1 <1×10

−33

− 64.55 ± 38.6*** − 70.95 ± 45.9*** − 59.59 ± 48.1*** − 71.31 ± 35.9***

Keller et al. Genome Medicine (2020) 12:97 Page 4 of 18

Table 1 Study characteristics of the CENTRAL subgroup selected for genome wide DNA methylation analysis (Continued)

Trait CENTRAL all (N = 120) P value Low carb (N = 30) Low carb + PA (N = 30) Low fat (N = 30) Low fat + PA (N = 30)

Superficial subcutaneous adipose

tissue area (cm

2

)

T

0

134.89 ± 56.5 146.20 ± 74.7 125.20 ± 47.6 135.90 ± 59.9 132.20 ± 37.9

T

18

106.76 ± 44.1 121.37 ± 55.8 94.4 ± 31.8 111.29 ± 50.3 99.99 ± 29.53

Δ

(T18-T0)

− 28.02 ± 23.9 <1×10

−23

− 24.85 ± 30.1*** − 30.85 ± 24.5*** − 24.01 ± 22.8*** − 32.23 ± 16.5***

Metabolic traits are shown as mean ± SD values prior intervention (T0), post-intervention (T18), and the intervention specific changes (Δ(T18-T0)). P values obtained from paired t-statistics between T0 and T18 are

shown for the entire cohort and indicated as: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001, for the intervention specific changes

Keller et al. Genome Medicine (2020) 12:97 Page 5 of 18

after the intervention (comparing T0 vs T18 over all 120

subjects).

Nevertheless, we used the sva R package to correct

beta values for cell-type composition in an attempt to

reduce noise [31].

DNA methylation changes

To identify intervention specific differentially methyl-

ated regions (DMRs) between T0 vs. T18 or differ-

ences at T18 as a result of t he individual

interventions, we used the DMR finder metilene [32].

Only DMRs were considered which carried a mini-

mum number of 3 CpGs per DMR with a maximum

distance of 1000 nt between the CpGs. Genes from

gencode v19 + 1500 nt upstream were intersected

using bedtools [33] with the DMRs to annotate the

genes. We compared T0 vs. T18, presence or absence

of physical activity (PA vs no), low-carb vs low-fat

diet, and PA vs no in the two dietary groups.

It has to be noted that methods used to interrogate

the data for DMRs can also result in distinctly different

findings. Therefore, we performed a single CpG analysis

using the dmpFinder function of the minfi package as

described in [26] (pages 18–21) [21].

Intervention independent changes (responders vs. non-

responders)

To investigate differences in DNA methylation levels be-

tween the top 10 responders and bot tom 10 non-

responders (including only men matched for age; Fig. 1a)

according to their relative weight-loss after intervention,

computed DNA methylation differences at the individual

time points (T0; T18) as well as combined data sets (T0

and T18) using metilene were employed to uncover

DMRs using the metilene’s two-dimensional

Kolmogorov-Smirno v test (2D-KS) under the same cri-

teria mentioned above [32]. Metabolic differences be-

tween the groups were calculated in SPSS (V.24) using t-

statistics.

Predicting methylation marks

To detect individual CpG sites on a genome-wide basis

which are associated with the success of weight-loss by a

classical lifestyle intervention (independent of the inter-

vention type), Spearman and Pearson correlation ana-

lysis were performed individually and combined to take

linearity an d monotony equally into account and to fur-

ther reduce potential background noise due to data

properties. An epigenome-wide association study

(EWAS) for the relative weight loss in % based on the

initial body weight (kg) was conducted and plotted using

CMplot in R [29]. A receiver operating characteristic

(ROC) curve model was used to further test a potential

predictive value of a baseline methylation score,

computed as mean of all ß values from CpG sites. We

used 4 methylation-based predictors, two based on CpGs

correlating negatively with intervention weight changes

with p < 0.001 and p < 0.0001 and two based on CpGs

correlating positively with weight changes: p < 0.001 and

p < 0.0001. We compared these 4 predictors to general

intervention predictors such as a linear combination of

individuals’ age and BMI (x*age + y*BMI). The analysis

was restricted to men ’s data sets for all ROC analysis, as

there is only a limited number of women and the com-

bination of age and BMI showed different behavior for

men’s and women’s data sets. The maximum area under

the ROC curve (AUC) was achieved for the coefficients

x = − 1 for the age and y = 2.54 for the BMI in the linear

combination ([26], pages 14–17).

Statistics

P value adjustment was performed using the Benjamini-

Hochberg procedure with adj.P values < 0.05 considered

to be statistically significant. Phenotype correlation ana-

lysis at both time points was performed with baseline

methylation levels of the identified candidate DMRs and

CpGs using again Pearson and Spearman analysis and

included the computation of a combined P via geometric

mean (

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

Q

n

i¼1

χi

n

s

).

ChromHMM prediction

All identified DMRs, as well as the putative EWAS CpGs

described above, were aligned to chromatin segments

taken from the Epigenomic Roadmap [34] as well as

additional cancer cell lines generated as described else-

where [35] using bedtools [ 33 ]. Besides analyzing a back-

ground of all cell and tissue types, we focused on AT

(adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells, mesen-

chymal stem cell-derived adipocyte cultured cells, adipo-

cyte nuclei), intestinal tissue (fetal intestine large, fetal

intestines small, small intestines), skeletal muscle

(HSMM cell-derived skeletal muscle myotube cells,

HSMM skeletal muscle myoblasts cells, skeletal muscle

female, skeletal muscle male), and liver tissue.

Gene ontology analysis

Probes from the DMRs characterizing methylation dif-

ferences between responders and non-responders (P <

0.05) as well as correlating probes (P < 0.05) were taken

forward for gene ontology analyses corrected for probe

abundance of the EPIC array using R’s missMethyl pack-

age [36 ] and 0.05 as cutoff for the false discovery rate

([26], page 27).

Keller et al. Genome Medicine (2020) 12:97 Page 6 of 18

Results

All subjects included in the DNA methylation analysis

lost on average 3.65 ± 5.2 kg (mean ± SD; P <1×10

−11

,

Table 1 and Fig. 1b) of body weight after 18 months

accounting for more than one BMI point. In line with

this, the area of visceral AT, deep and superficial

subcutaneous AT depots decreased significantly (all

P <1×10

−20

,Table1), and obesity-associated meta-

bolic features such as HbA1c and insulin levels clearly

improved (all P < 0.01, Table 1).

Specific signatures of DNA methylation between

responders and non-responders

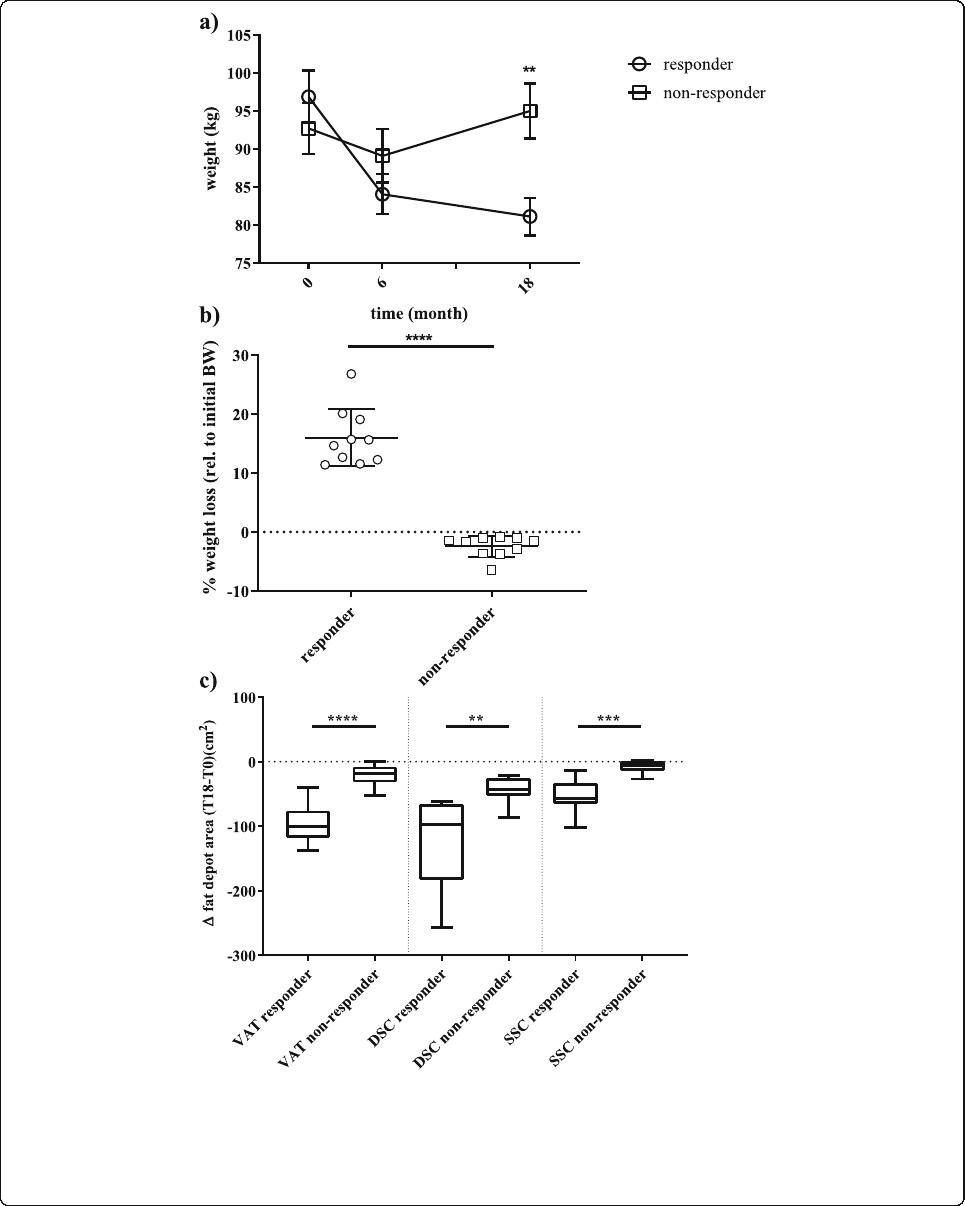

First, we conducted analyses to uncover regions po-

tentially discriminating between success and failure of

a lifestyle intervention, and we selected 10 male sub-

jects who were referred to as non-responders since

they slightly gained weight after intervention and 10

male responders showing the most pronounced

weight-l oss (Fig. 2a, b). The intervention group distri-

bution of responders and non-respo nders is provided

in Fig. 1a. Both, the top responders and the bottom

non-responders (matched with respect to age), lost

weight after the first 6 months of diet intervention

(Fig. 2a). However, during the following 12 months of

intervention, the non-responders regained or even ex-

celled their initial w eight whereas the responders lost

about 16% of their initial body weight (Fig. 2a, b).

Consistently, differences in the area of adipose depots

were found between the subgroups of responders and

non-responders after 18 months of intervention, with

the strongest difference for visceral AT (P <1×10

−5

,

Fig. 2c).

Between the two groups, we identified 293 DMRs

(2D-KS P value< 0.05; comprising 332 g enes; 33

DMRs without genes) at baseline, i.e., prior to lifestyle

intervention, and 280 DMRs (331 genes; 43 DMRs

without genes) after completion of the intervention.

However, both before and after intervention, only two

DMRs (mapped genes: CRISP2 and LRRC27)

remained significant after correction for multiple test-

ing (Additional file 2: Table S1 and S2). Neverthe less,

between both time points 150 DMRs corresponding

to 168 genes intersected with consisten t differe nces in

DNA methylation and were not muc h af fected by

weight-loss intervention. Therefore, to minimize the

effect of potential outliers by increasing the sample

size and so the statistical power, we combined the

datasets of both time-points treating the different

time-points as biolog ical replicates without any fur-

ther adjustments for the lack of independence and

thereby identified 669 DMRs (759 genes; 100 DMRs

without genes) between responders vs. non-

responders (Add itional file 2: Table S3). After

correction for multiple testing 8 DMRs (9 genes) (P

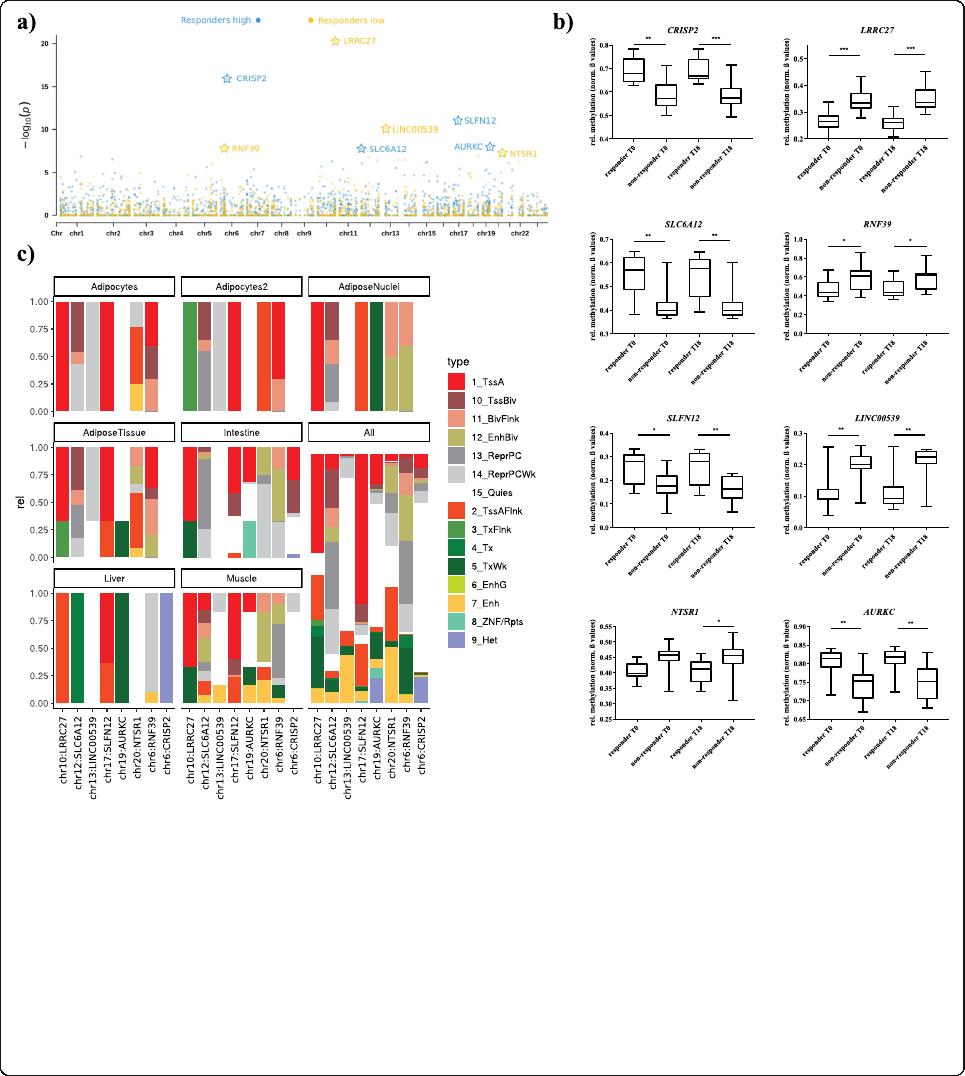

adjusted < 0.05) remained significant (Table 2, Fig. 3a).

Amongthem,4DMRsshowedsignificantlyhigher

(CRISP2, Cysteine Rich Secretory Protein 2; SLC6A12,

Solute Carrier Family 6 Member 12/RP11-283I3.2;

SLFN12, Schlafen Family Member 12; AURKC, Aurora

Kinase C; deltaM: 0.06–0.13) and 4 significant lower

methylations in responders (LRRC27, Leucine Rich Re-

peat Contain ing 27; RNF3 9, Ring Finger Protein 39;

LINC00539, Long Intergenic Non-Protein Coding RNA

539;andNTSR1, Neurotensin Receptor 1; deltaM: (−

0.08)-(− 0 .11))(Fig.3a/b; Table 2) compared to non-

responders. Diff erences in DNA methylation (normal-

ized ß values) for all 8 DMRs are presented in Fig. 3b.

Among them, the SLC6A12 (-RP11-283I3.2) gene

locus revealed the strongest difference in DNA

methylation (deltaM: 0 .126 = 12.6%; adjusted

P =

0.008) (Table 2; Fig . 3b) for a DMR at chr12:312736-

312753 including 3 CpG sites.

Furthermore, among the DMRs which showed signifi-

cant P values in a combined analysis but did not withstand

adjustment for multiple testing (N = 661), we identified

mostly new candidate genes but also confirmed genetic

risk loci for BMI (N = 256), waist-to-hip ratio (N =154),

waist-circumference (N = 55), and type 2 diabetes (N =

130), such as the Transcription Factor 7-Like 2 (TCF7L2)

(Additional file 2: Table S4, risk loci according to the

GWAS catalog data accessed 04/2020) [37]. Moreover, we

identified 280 genes for SAT and 267 for OVAT which

showed differential methylation between the obesity states

in a previous work by Keller et al. [10] and were overlap-

ping with genes potentially discriminating between re-

sponders and non-responders (Additional file 2:Table

S4). Among them, 19 genes in subcutaneous adipose tis-

sue (SAT) and 19 in omental visceral adipose tissue

(OVAT) further showed significant transcriptional

changes according to differences in metabolic state [10].

GO enrichment analysis unraveled differentially methyl-

ated genes between responders and non-responders which

annotate to biological processes mainly involved in differ-

ent types of cell-adhesion (e.g., GO:0007156; homophilic

cell adhesion via plasma membrane adhesion molecules;

FDR =8.31×10

−14

, Additional file 2:TableS5).

In silico analyses of identified DMRs

Further, we employed a ChromHMM prediction model

to functionally annotate the top differentially methylated

DMRs to specific tissues most likely relevant for obesity

development (e.g., AT derived stem cells) or other meta-

bolically related processes (e.g., skeletal muscle or liver).

Data shows RNF39 and SLFN12 to be located in an ac-

tive TSS for AT derived mesenchymal stem cells. While

for the other DMRs this seems to be ubiquitous among

most tissues, for RNF39 it is limited to AT (Fig. 3c).

Keller et al. Genome Medicine (2020) 12:97 Page 7 of 18

Fig. 2 Phenotypic differences between responders and non-responders to a lifestyle intervention. a shows the absolute weight of the responders

(N = 10) and non-responders (N = 10) subgroups over the three time points: baseline (T0), 6 months (T6), and 18 months (T18). Data is shown as

mean ± SD; b shows the relative (%, rel. to T0) weight-loss at 18 months for both subgroups. Data is shown as scatter dot plots (mean ± SD); c

shows the absolute changes of fat areas (cm2; VAT-visceral AT, DSC-deep subcutaneous AT, SCC- superficial subcutaneous AT) at 18 months

compared to the baseline area as boxplots (line = median) with whiskers representing min and max values; **P < 0.001;

***P <1×10

–3

; ****P <1×10

–4

Keller et al. Genome Medicine (2020) 12:97 Page 8 of 18

Table 2 Genetic regions discriminating responders from non-responders

Location Adj.P DeltaM Probes/DMR 2D-KS_p value SNPprobes Cross-reactive probes Genes Probes/gene

chr10:134150449-134150761 2.4E−15 − 0.082275 8 5E−21 0 0 LRRC27 81

chr6:49681176-49681392 6.1E−11 0.101266 8 1.3E−16 0 0 CRISP2 14

chr17:33759510-33760309 0.0000054 0.083168 12 1.1E−11 0 0 SLFN12 22

chr13:21919004-21919171 0.000038 − 0.090555 3 7.9E−11 0 3 LINC00539 39

chr19:57742110-57742424 0.005 0.05827 9 0.000000011 0 0 AURKC 16

chr6:30039130-30039802 0.0077 − 0.114807 18 0.000000016 3 0 RNF39 83

chr12:311645-313379 0.0082 0.126218 9 0.000000017 1 0 RP11-283I3.2, SLC6A12 9.59

chr20:61371016-61371809 0.024 − 0.041995 5 0.000000051 3 0 NTSR1 38

Differentially methylated DMRs between responders and non-responders to lifestyle intervention; including all datasets at baseline and post-intervention. Top candidate DMRs with adj. P ≤ 0.05. DeltaM represents the

difference of the mean average methylation rates between responders and non-responder as computed by metilene. The 2D-KS p value represents a two-dimensional variety of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test used by

metilene. Probes/DMR represents the number of probes within a DMR. SNPprobes represent probes containing a SNP with a frequency > 0.01. Cross-reactive probes indicate potential off-target probe binding. Genes is

a comma-separated list of the genes cis to the DMR, and probes/gene is the total number of probes that are cis to the respective genes. Chromosomal location was annotated to genome assembly GRCh37 (hg19)

Keller et al. Genome Medicine (2020) 12:97 Page 9 of 18

DNA methylation changes due to specific weight-loss

interventions

Based on the findings from responder vs. non-responder

analyses, we investigated whether different lifestyle inter-

vention (dietary MED/LC vs LF) and PA had a

recognizable impact on CpG methylation in human blood

in an expanded analysis including all samples from all in-

terventions together (N = 120; T0 vs T18; Additional file 2:

Table S6). Thereby we identified 1146 CpG mapping to

1459 genes (84 CpGs with no gene) with a significant

methylation change (q value, < 0.05). Interestingly, the in-

dividual interventions (LF + PA; MED/LC + PA; LF-PA;

MED/LC-PA) did not show significant changes on CpG

(all q value > 0.05) or DMR (all adj. P > 0.05) specific DNA

methylation levels (Additional file 2:TablesS6–7). Of

note, we identified two DMRs on chromosome 1 (2D-KS

Fig. 3 Candidate genes discriminating responders from non-responders. a Combined P values presented as Manhattan plot for differently

methylated DMRs between responders vs. non-responders on a genome-wide scale; blue dots indicate regions were responders showed

significantly lower, green dots significantly higher methylation levels compared to non-responders; genes marked with a star remained significant

after correction for multiple testing (adj. P < 0.05), b Methylation levels at the identified genes between responders and non-responders

presented as box plots (normalized ß values) with whiskers representing min and max values, **P < 0.001; ****P <1×10

−4

. c ChromHMM

prediction for the significant DMRs (adj. P < 0.05). To identify putative target genes in the phenotype relevant target tissues: Intestine (Fetal-

Intestine-Large, Fetal-Intestine-Small, Small-Intestines), Adipos-Nuclei (Adipose-Nuclei), AdiposeTissue (Adipose-Nuclei, Adipose-Derived-

Mesenchymal-Stem-Cell-Cultured-Cells, Mesenchymal-Stem-Cell-Derived-Adipocyte-Cultured-Cells), Adipocytes (Mesenchymal-Stem-Cell-Derived-

Adipocyte-Cultured-Cells), Adipocytes2 (Adipose-Derived-Mesenchymal-Stem-Cell-Cultured-Cells) Liver (Liver), Muscle (HSMM-cell-derived-Skeletal-

Muscle-Myotubes-Cells, HSMM-Skeletal-Muscle-Myoblasts-Cells, Skeletal-Muscle-Female, Skeletal-Muscle-Male), and all (all 134 cells from Roadmap

Epigenome Gateway). ChromHMM coding for TssA-active TSS, TssBiv-Bivalent (Poised) TSS, BivFlnk-Bivalent Flanking, EnhBiv-Bivalent Enhancer,

ReprPC-Polycomb Repressed, ReprPCWk-Weakly Polycomb Repressed, Quies-Quiescent/low, TssAFlnk-Flanking TSS, TxFlnk-Flanking Transcribed, Tx-

Transcribed, TxWk-Weakly Transcribed, EnhG- Genetic Enhancer, Enh –Enhancer, ZNF/Rpts-ZNF Genes and Repeats, He-Heterochromatin

Keller et al. Genome Medicine (2020) 12:97 Page 10 of 18