METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS A VOLUME 29A, OCTOBER 1998—2503

Factors Influencing the Equilibrium Grain Size in Equal-

Channel Angular Pressing: Role of Mg Additions to Aluminum

YOSHINORI IWAHASHI, ZENJI HORITA, MINORU NEMOTO, and

TERENCE G. LANGDON

Experiments were undertaken to compare the equal-channel angular (ECA) pressing of Al-1 pct Mg

and Al-3 pct Mg solid-solution alloys with pure Al. The results reveal both similarities and differ-

ences between these three materials. Bands of subgrains are formed in all three materials in a single

passage through the die, and these subgrains subsequently evolve, on further pressings through the

die, into an array of grains with high-angle boundaries. However, the addition of magnesium to an

aluminum matrix decreases the rate of recovery and this leads, with an increasing Mg content, both

to an increase in the number of pressings required to establish a homogeneous microstructure and

to a decrease in the ultimate equiaxed equilibrium grain size. It is concluded that alloys exhibiting

low rates of recovery should be especially attractive candidate materials for establishing ultrafine

structures through grain refinement using the ECA pressing technique.

I. INTRODUCTION

It is now established that ultrafine grain sizes, in the

submicrometer or nanometer range, may be introduced into

polycrystalline metals through the use of an intense plastic

straining technique known as equal-channel angular (ECA)

pressing.

[1,2]

In this procedure, a sample is pressed through

a die in which two channels, equal in cross section, intersect

at an angle of F, with an additional angle of C defining

the arc of curvature at the outer point of the intersection of

the two channels. The use of the ECA pressing technique

has two advantages, in that it introduces no porosity into

the material and it offers the potential for making large bulk

samples.

Earlier reports described the ECA pressing of pure Al,

[3]

an Al-3 pct Mg solid-solution alloy

[4,5]

and a commercial

Al-Mg-Li-Zr alloy

[6,7]

to produce equilibrium grain sizes of

;1, ;0.2, and ;1.2

m

m, respectively. The reason for these

differences in the ultimate stable grain size is not under-

stood at the present time, and the measured grain sizes ap-

pear not to correlate to the temperature of pressing because

the pure Al and Al-3 pct Mg alloy were both pressed at

room temperature whereas the Al-Mg-Li-Zr alloy was

pressed at 673 K. Furthermore, Ferrasse et al.

[8,9]

pressed

samples of CDA 101 oxygen-free copper and Al-3003 and

Al-6061 alloys under identical conditions and reported

achieving the same equilibrium grain sizes of ;0.2 to

;0.4

m

m in each material. From the limited results available

to date, no firm conclusions can be reached concerning the

factors which influence the ultimate stable grain sizes in

ECA pressing experiments.

YOSHINORI IWAHASHI, formerly Graduate Student with the

Department of Materials Science and Engineering, Kyushu University, is

Staff Engineer, Nagasaki Shipyard and Machinery Works, Mitsubishi Heavy

Industries, Ltd., Fukahori, Nagasaki 851-03, Japan. ZENJI HORITA,

Associate Professor, and MINORU NEMOTO, Professor, are with the

Department of Materials Science and Engineering, Kyushu University,

Fukuoka 812-8581, Japan. TERENCE G. LANGDON, Professor, is with

the Departments of Materials Science and Mechanical Engineering,

University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90089-1453.

Manuscript submitted December 30, 1997.

The present investigation was undertaken in order to pro-

vide information on the variation of the equilibrium grain

size established by ECA pressing in samples of aluminum

with Mg additions. Magnesium was selected as the alloying

element because it is well known that the presence of Mg

atoms reduces the dislocation mobility and introduces solid-

solution strengthening, and this increase in strength is ac-

companied by little or no change in the overall ductility of

the material.

[10]

In addition, the presence of Mg in solid

solution gives rise to shear band formation during the cold

rolling of aluminum,

[11]

and this may have important con-

sequences when ECA pressing is performed at room tem-

perature.

II. EXPERIMENTAL MATERIAL AND

PROCEDURES

A. Materials

Tests were undertaken using the following two Al-Mg

alloys.

(1) An Al-1.0 wt pct Mg solid-solution alloy, equivalent to

Al-1.1 at. pct Mg, with 0.003 pct Si and 0.001 pct Fe

as minor impurities. This material was received in the

form of a cold-rolled billet with a width of 150 mm, a

thickness of 25 mm, and a length of ;1 m. A block

having dimensions of 150 3 25 3 100 mm

3

was cut

from the billet. For an ECA pressing facility with a

square cross section, the block was rolled at room tem-

perature to a final thickness of ;12 mm and then bars,

having dimensions of 10 3 10 3 60 mm

3

, were cut,

ground, and annealed at 773 K for 1 hour. For a press-

ing facility with a circular cross section, rods were cut

with dimensions of 25 3 25 3 150 mm

3

and these rods

were swaged to a diameter of 10 mm, cut into lengths

of 60 mm, and then annealed for 1 hour at 773 K.

Microstructural observations revealed a grain size of

;500

m

m prior to ECA pressing.

(2) An Al-3.0 wt pct Mg solid-solution alloy, equivalent to

Al-3.3 at. pct Mg, with 0.004 pct Si and 0.001 pct Fe

as minor impurities. The sample preparation for this

2504—VOLUME 29A, OCTOBER 1998 METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS A

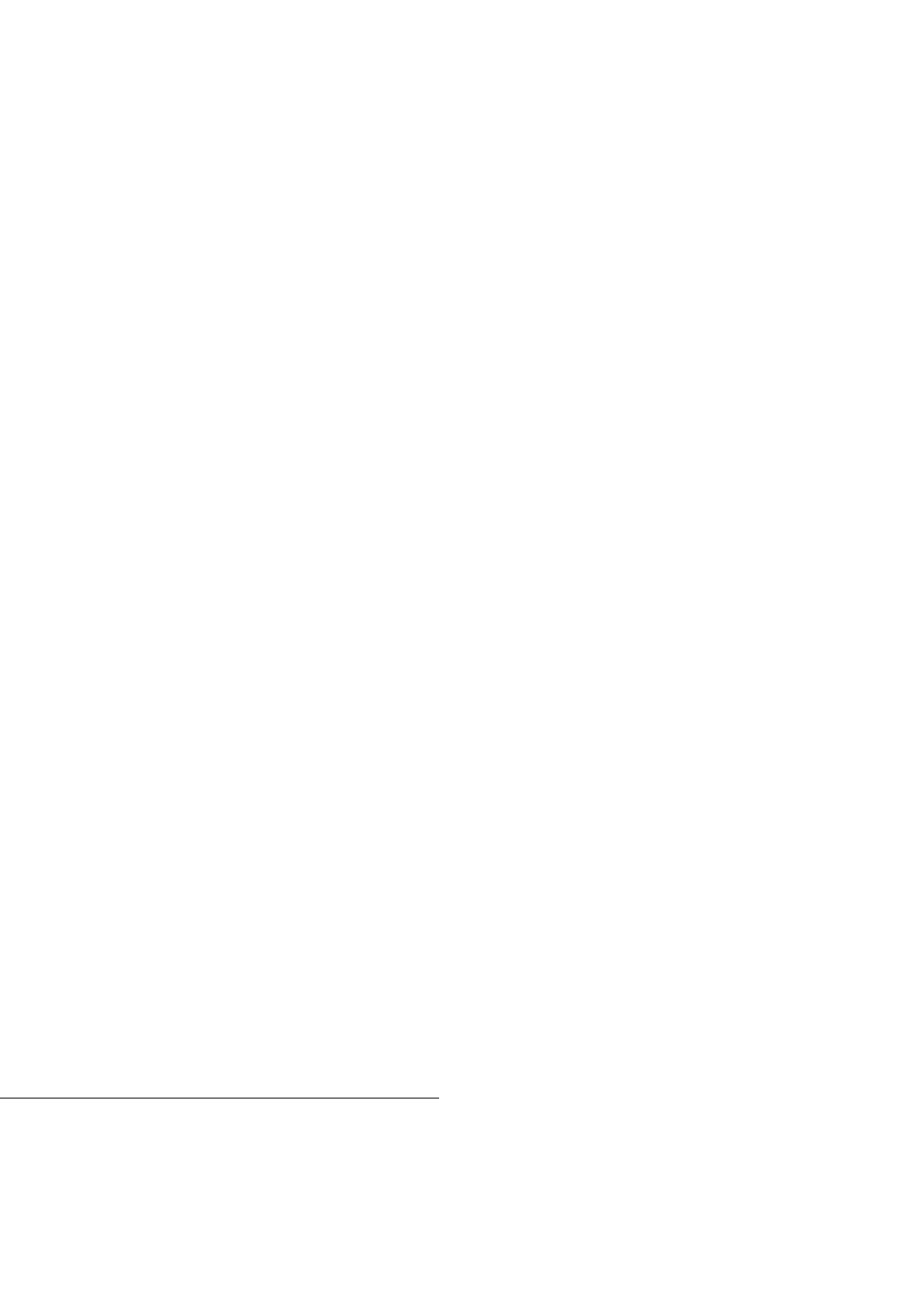

Fig. 1—Microstructures in Al-1 pct Mg after a single passage through the

die together with the corresponding SAED patterns.

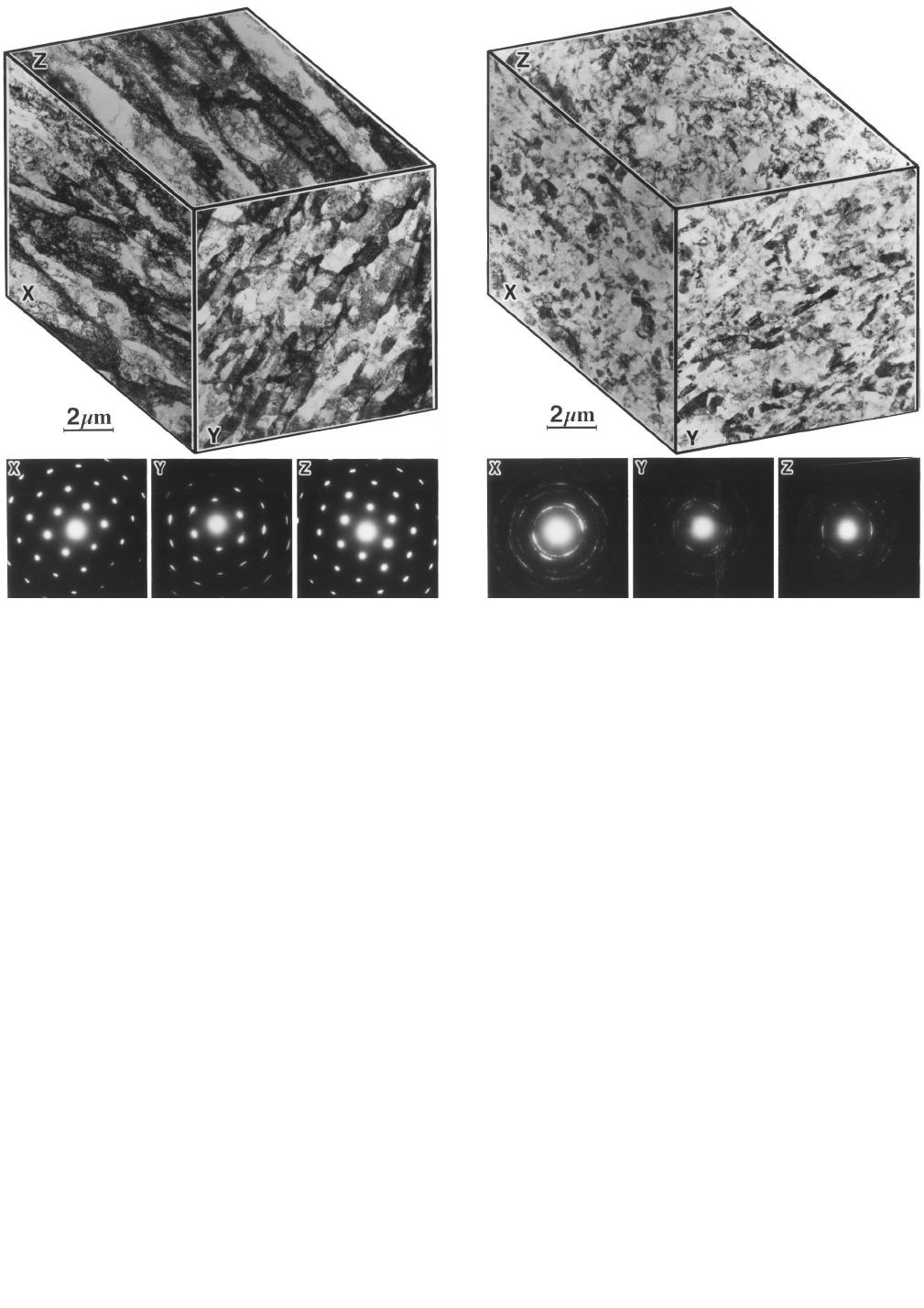

Fig. 2—Microstructures in Al-1 pct Mg after four pressings using route

B together with the corresponding SAED patterns.

material prior to ECA pressing was identical to that of

the Al-1 pct Mg alloy. The grain size of this alloy after

annealing for 1 hour at 773 K was also ;500

m

m.

For comparison purposes, some additional experiments

were also conducted using samples of pure (99.99 pct) alu-

minum cut from a cold-rolled plate. Prior to ECA pressing,

this material was annealed for 1 hour at 773 K to give a

measured grain size of ;1.0 mm. Further details of the

specimen preparation for pure Al were given previously.

[3,12]

B. ECA Pressing Facility

Two different ECA pressing facilities were used in this

work, with the channels having either square or circular

cross sections.

The ECA pressing facility with the channel having a

square cross section had entrance and exit channels of 10.3

3 10.3 mm

2

and 10 3 10 mm

2

, respectively, and the angles

associated with the channel were F590 deg and C . 20

deg. The die was constructed by using several pieces of

SKD11 tool steel (Fe-1.4 to 1.6 pct C, 11 to 13 pct Mn,

0.8 to 1.2 pct Cr, 0.2 to 0.5 pct V) and assembling these

pieces into an L-shaped channel which was held together

by bolting it between two flat blocks of tool steel. This

improved facility had the advantage of avoiding any break-

ing which may occur at the sharp corners when, as in earlier

experiments,

[12]

a single channel was machined directly into

one of the two blocks. The second pressing facility had a

channel with a circular cross section, with diameters of 10.3

and 10 mm at the entrance and exit, respectively, and with

F590 deg and C . 90 deg. This die was constructed by

mechanically drilling and grinding a single channel into a

solid block of SKD11 tool steel.

In practice, it was found that both facilities gave essen-

tially identical microstructures after any selected number of

pressings. Therefore, for convenience, no further distinction

will be made between the samples pressed using these two

different facilities.

C. Procedure for ECA Pressing

All of the ECA pressing was conducted at room temper-

ature, with a pressing speed of ;19 mm s

21

, using MoS

2

as a lubricant. The strain introduced during a single passage

through the die may be estimated by substituting the ap-

propriate values of F and C into a relationship derived

earlier

[13]

which has been shown through model experiments

to provide an accurate estimate of the strain in the absence

of any effects associated with friction at the channel

walls.

[14]

Specifically, the relationship predicts that each

pressing, for both dies, gives a strain which is close to ;1;

repetitive pressings of the same sample were performed in

these experiments to achieve high strains.

When conducting repetitive pressings, it is possible to

define three distinct processing routes: route A denotes re-

petitive pressings without rotation of the sample, route B

denotes repetitive pressings where the sample is rotated in

the same direction by 90 deg between each pressing, and

route C denotes repetitive pressings where the sample is

rotated by 180 deg between each pressing. These process-

METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS A VOLUME 29A, OCTOBER 1998—2505

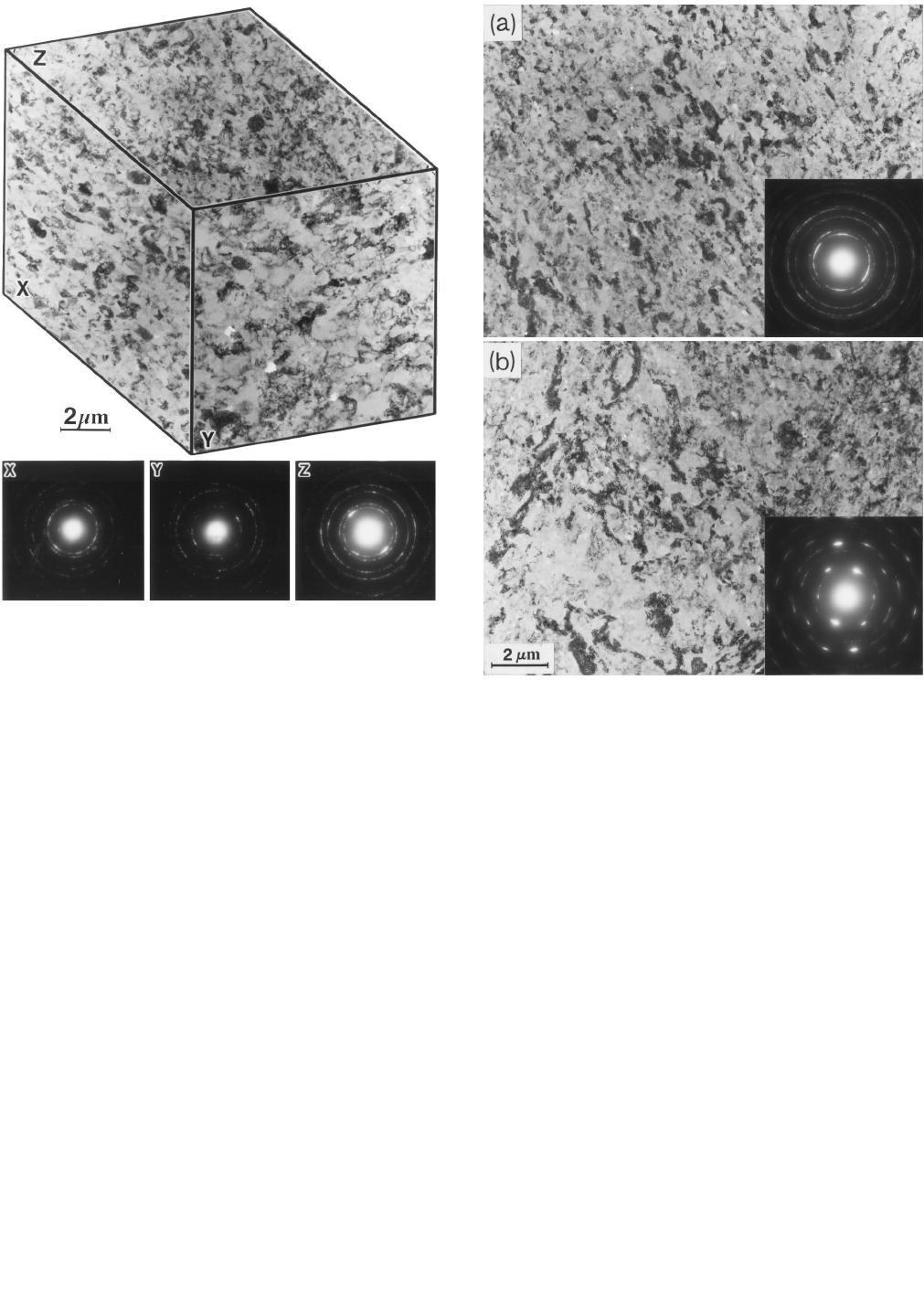

Fig. 3—Microstructures in Al-1 pct Mg after six pressings using route B

together with the corresponding SAED patterns.

Fig. 4—Microstructures and SAED patterns for Al-3 pct Mg after six

pressings using route B showing regions with boundaries having (a) high

angles and (b) low angles.

ing routes lead to different microstructural results because

of the concomitant changes in the shearing patterns within

the crystalline material. In practice, it was shown earlier

that route B is generally preferable because it accelerates

the attainment of an array of high-angle grain boundaries.

[12]

As a consequence of this earlier observation, most of the

tests in the present investigation were conducted using route

B.

D. Microstructural Examination

Microstructural observations were made by transmission

electron microscopy (TEM) after ECA pressing, using spec-

imens prepared from sections of the pressed samples cut in

three mutually perpendicular directions, where the x plane

is perpendicular to the longitudinal axis of the pressed sam-

ple and the y and z planes lie parallel to the side faces and

the top surface of the sample at the point of exit from the

die, respectively. Selected-area electron diffraction (SAED)

patterns were taken from regions having diameters of 12.3

m

m. Full details of the procedure for TEM observations

were given earlier.

[3]

E. Tensile Testing after ECA Pressing

An electrical spark discharge machine was used to pre-

pare tensile specimens, after ECA pressing, with gage

lengths perpendicular to the x plane and with gage sections

having lengths of 12 mm and cross sections of 3.5 3 2.2

mm

2

. All tensile tests were conducted in air at room tem-

perature, using a testing machine operating at a constant

rate of cross-head displacement with an initial strain rate of

3.3 3 10

24

s

21

.

III. EXPERIMENTAL RESULTS

A. Microstructural Observations

An earlier report gave a detailed description of the mi-

crostructural development in samples of pure Al and, in

particular, it was noted that a homogeneous equiaxed mi-

crostructure was achieved after four repetitive pressings

when using a 90 deg rotation between each pressing in the

procedure designated as route B.

[12]

These earlier observa-

tions are not repeated here, but emphasis will be placed

instead on the ECA pressing of the Al-Mg alloys using

route B in order to identify the significance of the Mg ad-

ditions under optimum pressing conditions.

1. Al-1 pct Mg alloy

Figure 1 shows the microstructures and the associated

SAED patterns in the x, y, and z planes after a single pas-

sage of the Al-1 pct Mg alloy through the die. As with pure

Al,

[12]

the structure is divided into an array of parallel bands

2506—VOLUME 29A, OCTOBER 1998 METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS A

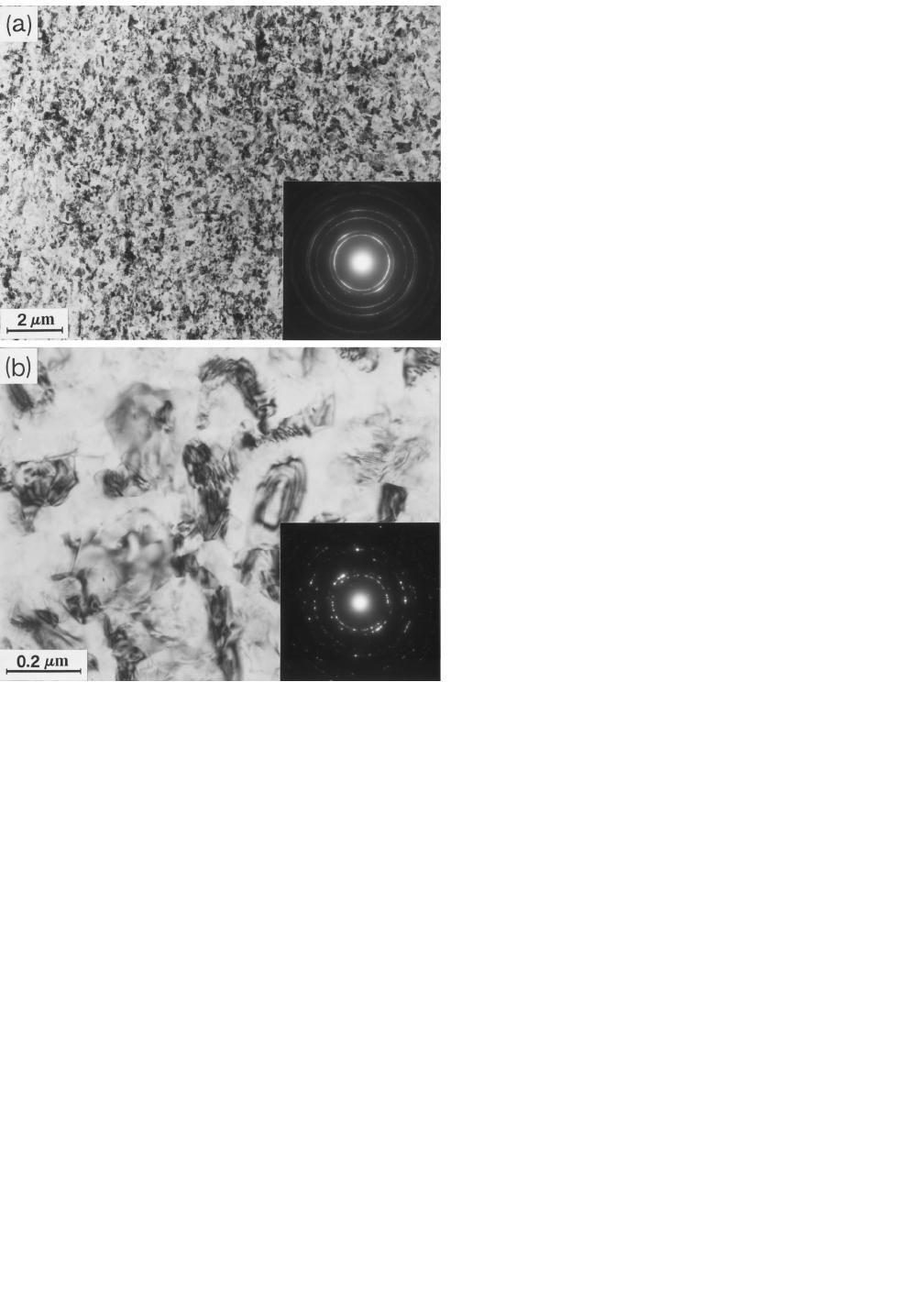

Fig. 5—Microstructures and SAED patterns for Al-3 pct Mg after eight

pressings using route B at (a) low and (b) high magnifications.

of subgrains, with the bands lying essentially parallel to the

shearing direction at 45 deg to the top and bottom edges

of the y plane, perpendicular to the direction of flow in the

z plane, and approximately parallel to the top and bottom

edges of the pressed sample in the x plane. Although these

microstructural trends appear essentially identical to those

reported for pure Al,

[12]

close inspection shows that the av-

erage width of the subgrain bands is significantly smaller

than in the pure Al and, in addition, there is a higher density

of dislocations contained within each subgrain. It is appar-

ent from the SAED patterns that these boundaries have low

angles of misorientation.

Figure 2 shows the microstructures and SAED patterns

achieved in the Al-1 pct Mg alloy after a total of four press-

ings through the die, using processing route B. In this con-

dition, the microstructure is reasonably equiaxed and

homogeneous in the x and z planes but, nevertheless, there

remains some evidence for the presence of a banded struc-

ture in the y plane. This observation contrasts with that for

pure Al, where the grains were essentially equiaxed in all

three planes of sectioning after a total of only four pressings

using route B.

[12]

Thus, an immediate conclusion from these

experiments is that the addition of only 1 pct of Mg to the

aluminum metal serves, at least partially, to retard the ev-

olution of the equiaxed microstructure. It is apparent from

Figure 2 that the SAED patterns now form diffracted beams

which are scattered around rings, thereby indicating that, as

in pure Al after four pressings,

[12]

the misorientations of

many of the boundaries have evolved into high angles.

The effect of additional pressings is illustrated in Figure

3 for a sample subjected to six passages through the die,

using route B. The grains after six pressings are fairly

equiaxed and almost homogeneously distributed in each of

the x, y, and z planes, the grain boundaries have high angles

of misorientation, and it is apparent that the grain size is

very small.

2. Al-3 pct Mg alloy

A series of pressings of the Al-3 pct Mg alloy, for dif-

ferent numbers of passages through the die, revealed that

the evolution of a homogeneous equiaxed configuration of

grains occurred even more slowly in this material than in

the Al-1 pct Mg alloy. This trend is illustrated by the two

microstructures shown in Figure 4, taken from the x plane

after a total of six pressings using route B. In Figure 4(a),

the microstructure shows a fairly equiaxed array of grains

which, based on the SAED pattern, contains grain bound-

aries having high angles of misorientation: this result is,

therefore, consistent with observations on the Al-1 pct Mg

alloy after six pressings, as shown in Figure 3. However,

it is also apparent from Figure 4(b), showing another area

taken from the same specimen, that there remain some areas

of subgrains where the boundaries have low angles of mis-

orientation, as illustrated by the net pattern from an orien-

tation close to [110]. Thus, the Al-3 pct Mg alloy exhibits

a markedly inhomogeneous microstructure after a total of

six pressings, and there are separate and interspersed

regions containing grains having either high or low angles

of misorientation.

Since it was not possible to achieve a homogeneous

equiaxed structure in the Al-3 pct Mg alloy after six press-

ings, an additional sample was pressed through the die to

a total of eight pressings. Typical microstructures after eight

pressings are shown in Figure 5 for the x plane at (a) low

and (b) high magnifications, respectively. Careful inspec-

tion in this condition led to the conclusion that the micro-

structure was essentially homogeneous, with almost all of

the boundaries having high angles of misorientation, as il-

lustrated by the well-defined rings in the SAED pattern in

Figure 5(a) and the clear presence of individual diffraction

spots scattered around each ring in Figure 5(b). It is ap-

parent also, from a comparison of Figures 5(a) and 3, that

the grain size in the Al-3 pct Mg alloy is even smaller than

in the Al-1 pct Mg alloy after six pressings. At the higher

magnification in Figure 5(b), many of the grain boundaries

are not well defined and the visible boundaries are generally

curved instead of straight. This feature of poorly defined

and curved boundaries is consistent with earlier reports, ob-

tained using high-resolution electron microscopy, showing

the development of arrays of high-energy nonequilibrium

grain boundaries and the presence of high densities of dis-

locations in Al-Mg alloys after intense plastic straining us-

ing a torsion straining procedure.

[15]

B. Boundary Misorientations

The spreading of the spots in the SAED patterns was

used to provide information on the average misorientations

METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS A VOLUME 29A, OCTOBER 1998—2507

(a)

(b)

Fig. 6—Variation of the spreading of spots in the SAED patterns with number of pressings for (a) Al-1 pct Mg and (b) Al-3 pct Mg.

between the grains visible in the aperture.* Figure 6 shows

*It should be noted that the SAED patterns were obtained in this

investigation using a 12.3

m

m aperture, which includes diffraction spots

from numerous grains. Thus, the measured spot spreading does not

provide a quantitative measure of the misorientations between neighboring

grains but, nevertheless, by maintaining a constant aperture size, the

spreading may be used as a qualitative measure of the evolution of the

boundary misorientations during repetitive strainings.

[12]

A full

characterization of the individual boundary misorientations requires an

alternative procedure such as EBSD analysis, and this work is currently

in progress; a detailed report of these quantitative measurements will be

given later.

the variation of the spreading of the spots with the number

of pressings through the die for (a) the Al-1 pct Mg and

(b) the Al-3 pct Mg alloys, respectively, with the data fur-

ther divided to distinguish between routes A, B, and C and

with individual data points shown for measurements in the

x, y, and z planes. For both alloys and each processing

route, the spreading and, therefore, the average angle of

misorientation of the boundaries increases with an increas-

ing number of pressings through the die and, therefore, with

an increasing strain. Close inspection of the data shows that

the evolution into high angles of misorientation occurs

more slowly in the Al-3 pct Mg alloy, but the evolution is

consistently more rapid in the y plane in both alloys. This

observation is reasonable because this plane is associated

with maximum shearing. A comparison with the earlier data

documented for pure Al.

[12]

shows that the overall rate of

evolution in misorientation angle is fairly similar in pure

Al and in the Al-1 pct Mg alloy. In addition, evolution into

high-angle boundaries occurs more rapidly in these alloys

when using processing route B.

C. Grain Size

The grain size of each sample was measured carefully in

the x plane of each material after attaining a homogeneous

and equiaxed structure. These measurements revealed a sig-

nificant decrease in the ultimate equilibrium grain size with

increasing Mg addition, with stabilized grain sizes of ;1.3,

;0.45, and ;0.27

m

m for the pure Al, the Al-1 pct Mg

alloy, and the Al-3 pct Mg alloy, respectively. This de-

crease in grain size with increasing Mg addition is consis-

tent with the reduction in the widths of the subgrain bands

in the Al-Mg alloys.

D. Stress-Strain Behavior before and after ECA Pressing

Following ECA pressing under the optimum condition of

route B, samples were pulled to failure in tension at an

initial strain rate of 3.3 3 10

24

s

21

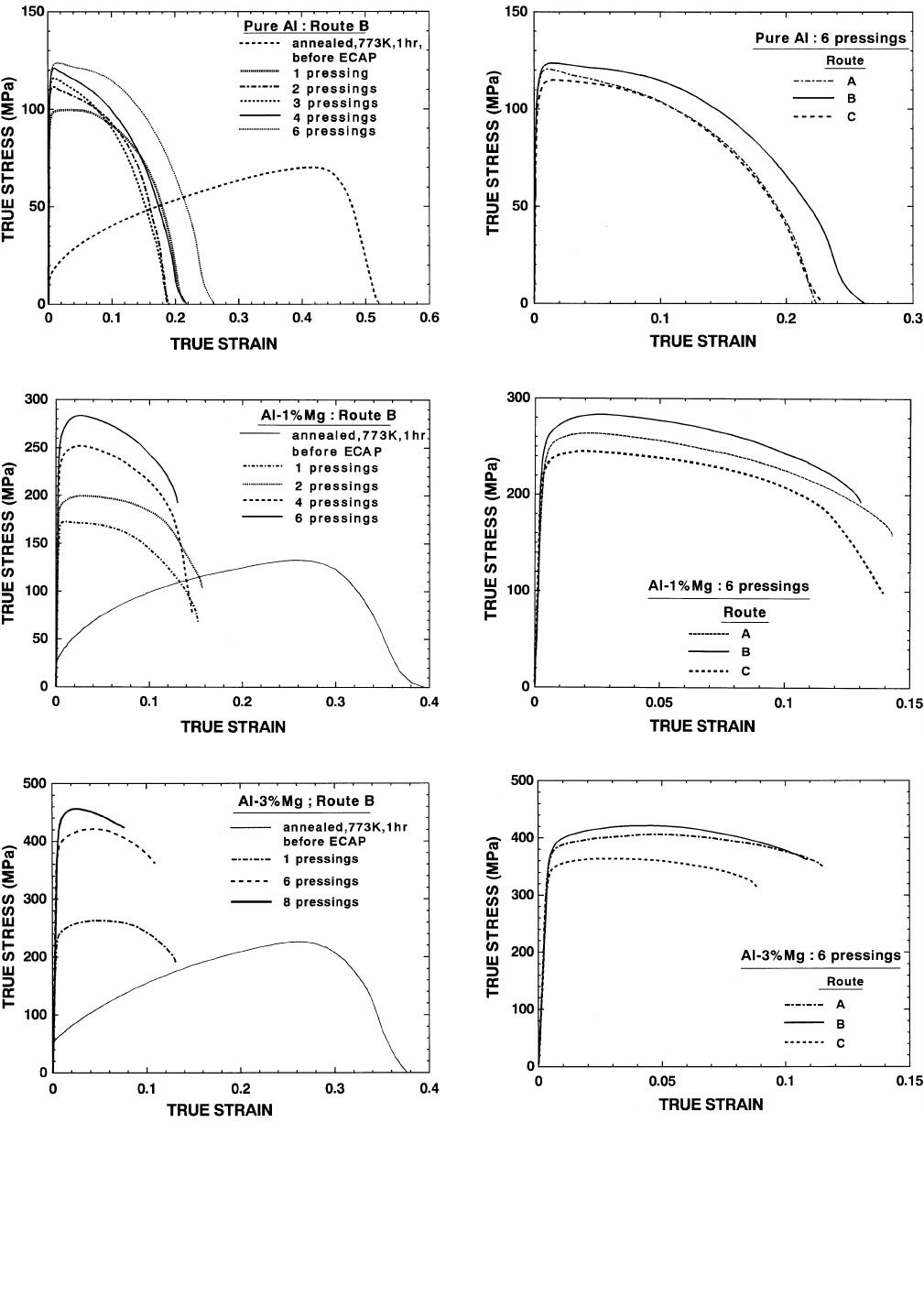

. Figure 7 shows the

2508—VOLUME 29A, OCTOBER 1998 METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS A

(a)

(b)

(c)

Fig. 7—True stress vs true strain for (a) pure Al, (b) Al-1 pct Mg, and

(c) Al-3 pct Mg pressed using route B.

(a)

(b)

(c)

Fig. 8—True stress vs true strain after six pressings for (a) pure Al, (b)

Al-1 pct Mg, and (c) Al-3 pct Mg using routes A, B, and C.

stress-strain curves for (a) pure Al, (b) Al-1 pct Mg, and

(c) Al-3 pct Mg, respectively; for comparison purposes,

Figure 7 includes also the appropriate curves for each ma-

terial in the unpressed condition with a very large grain

size following annealing for 1 hour at 773 K. Two conclu-

METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS A VOLUME 29A, OCTOBER 1998—2509

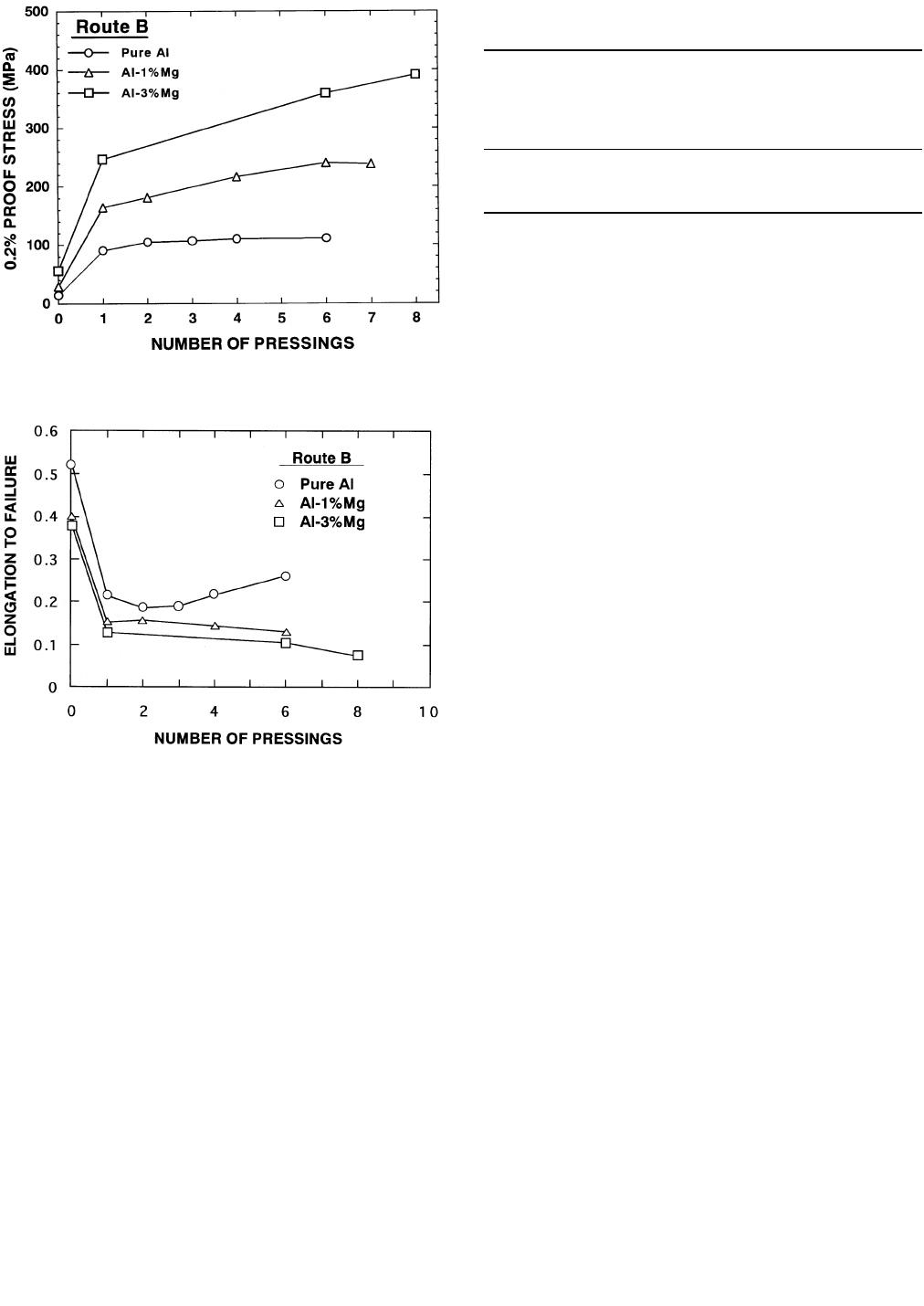

Fig. 9—The 0.2 proof stress vs number of pressings for pure Al, Al-1 pct

Mg, and Al-3 pct Mg pressed using route B.

Fig. 10—Elongation to failure vs number of pressings for pure Al, Al-1

pct Mg, and Al-3 pct Mg pressed using route B.

Table I. Characteristics of ECA Pressing at Room

Temperature Using Processing Route B

Material

Number of

Pressings to

Establish a

Homogeneous

Microstructure

Ultimate Stable

Grain Size (

m

m)

Pure Al (99.99 pct) 4 ;1.3

Al-1 pct Mg 6 ;0.45

Al-3 pct Mg 8 ;0.27

sions may be drawn from inspection of these curves. First,

in the annealed but unpressed condition, all materials give

stress-strain curves exhibiting extensive strain hardening

over a wide range of strain, whereas after ECA pressing,

even for a single passage through the die, there is little or

no significant strain hardening but, instead, the flow stress

increases rapidly and reaches a maximum within a strain

of ,0.04. Second, in all three materials there is a system-

atic increase in the value of the flow stress with additional

pressings through the die and, therefore, with increasing

strain.

To provide information on the effect of the processing

route, Figure 8 shows similar stress-strain curves for routes

A, B, and C after a total of six pressings for (a) pure Al,

(b) Al-1 pct Mg, and (c) Al-3 pct Mg, respectively. In each

material, the flow stress is slightly higher for route B, in-

termediate for route A, and lowest for route C. This result

reflects the consistently more-rapid evolution into a ho-

mogeneous equiaxed structure when using route B.

The 0.2 pct proof stress is plotted in Figure 9 as a func-

tion of the number of pressings for the three materials tested

using route B. In each case, there is a rapid increase in

stress after a single pressing but, thereafter, there is only a

very minor increase with further pressings in the pure Al

whereas there is a more substantial increase in stress in the

two Al-Mg alloys. The results for the pure Al reflect earlier

observations that the Vickers microhardness in this material

increases by a factor of .2 after a single pressing through

routes A and C and, thereafter, increases by only a very

small amount.

[3]

Figure 9 suggests also that the slope of the

plot beyond the first pressing increases with increasing Mg

additions.

Each of the specimens was pulled to failure in tension,

and Figure 10 shows the variation of the elongation to fail-

ure with the number of pressings, using route B, for sam-

ples of (a) pure Al, (b) Al-1 pct Mg, and (c) Al-3 pct Mg,

respectively. Each material exhibits a sharp drop in the

elongation after a single pressing and, subsequently, the

elongation increases slightly above ;3 pressings for pure

Al, whereas for the two Al-Mg alloys the elongation con-

tinues to decrease up to the maximum number of pressings

performed in these experiments. This difference in behavior

between the three materials is associated with the more

rapid attainment of a stabilized microstructure in the pure

Al.

IV. DISCUSSION

The results from this investigation show several similar-

ities between the ECA pressing of dilute Al-Mg solid-so-

lution alloys and pure Al. In all materials, a single passage

through the die at room temperature introduces an array of

subgrains, and these subgrains lie in well-defined bands es-

sentially parallel to the direction of maximum shear. The

subgrains are delineated by boundaries having low angles

of misorientation, but these boundaries evolve into high-

angle boundaries with subsequent pressings through the die.

Ultimately, in all three materials studied in this investiga-

tion, the microstructure reaches a homogeneous and

equiaxed array of grains separated by boundaries having

high angles of misorientation.

Despite these similarities, the addition of Mg to the alu-

minum matrix has two clear effects on the subsequent mi-

crostructural evolution: these effects are apparent from

inspection of Table I. First, there is an increase, with in-

creasing Mg content, in the number of pressings required

to establish a homogeneous microstructure in the material.

Second, the ultimate equiaxed equilibrium grain size at-

tained by ECA pressing decreases with an increasing ad-

dition of Mg, and this reduction is exceptionally marked,

by a factor of ;3, even for the addition of only 1 pct of

Mg.

2510—VOLUME 29A, OCTOBER 1998 METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS A

In order to understand the influence of Mg additions to

aluminum, it is first necessary to examine the precise effect

of adding magnesium in solid solution. It is well established

that the presence of Mg atoms in an Al matrix leads to

solid-solution strengthening by reducing the dislocation

mobility. In the ECA pressing of pure Al and Al-Mg alloys,

very large numbers of dislocations are introduced on the

first passage through the die because of the intense plastic

shearing. However, dislocation mobility is reduced in the

Al-Mg alloys and the rate of recovery is, therefore, slower

than in pure Al, so that additional straining and, therefore,

further pressings through the die are required in order to

attain a reasonably homogeneous microstructure. It is rea-

sonable to anticipate also that the higher density of dislo-

cations remaining in the Al-Mg alloys, as compared to pure

Al, will lead to a more complex slip pattern and, therefore,

as observed experimentally, to a refinement of the equilib-

rium microstructure.

Two experimental observations are available from this

study to confirm the easier recovery in pure Al as compared

to the Al-Mg alloys. First, the observations reported earlier

on pure Al after ECA pressing showed that the grain

boundaries were reasonably straight and smooth,

[3,12]

whereas, as illustrated in Figure 5(b), the boundaries are

poorly defined and generally curved after ECA pressing of

the Al-Mg solid-solution alloys. Second, the increase in the

elongation to failure in pure Al at and above four pressings,

as shown in Figure 10, is consistent with the more rapid

attainment in this material of a stable equilibrated micro-

structure.

From these experiments, it is reasonable to conclude that

alloys exhibiting low rates of recovery should be especially

attractive materials for attaining exceptionally small grain

sizes through the use of the ECA pressing technique.

V. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

1. The ECA pressing was conducted at room temperature

on samples of Al-1 pct Mg and Al-3 pct Mg solid-so-

lution alloys and comparisons were made to pure Al.

The results show that all three materials exhibit the for-

mation of bands of subgrains on a single passage

through the die and the subsequent evolution, with ad-

ditional pressings, into an array of equiaxed grains hav-

ing high-angle grain boundaries.

2. The experiments demonstrate that the addition to an Al

matrix of Mg atoms in solid solution has two important

consequences: (a) there is an increase in the number of

pressings necessary to establish a homogeneous and

equiaxed microstructure, and (b) there is a significant

decrease in the grain size attained ultimately in the stable

equiaxed condition.

3. The effects of Mg additions are attributed to the reduc-

tion in dislocation mobility and to the consequent lower

rates of recovery in the solid solution alloys. It is con-

cluded that materials having low rates of recovery

should be especially attractive for the production of ul-

trafine microstructures through grain refinement using

the procedure of ECA pressing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Mr. Moritaka Hiroshige (Nishiki

Tekko Co., Kurume, Fukuoka, Japan) for fabricating the

ECA pressing die with a single circular channel. This work

was supported in part by the Light Metals Educational

Foundation of Japan, in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Scien-

tific Research from the Ministry of Education, Science,

Sports and Culture of Japan, in part by the Japan Society

for the Promotion of Science, and in part by the National

Science Foundation of the United States under Grant Nos.

DMR-9625969 and INT-9602919.

REFERENCES

1. R.Z. Valiev and N.K. Tsenev: in Hot Deformation of Aluminum

Alloys, T.G. Langdon, H.D. Merchant, J.G. Morris, and M.A. Zaidi,

eds., TMS, Warrendale, PA, 1991, pp. 319-29.

2. R.Z. Valiev, N.A. Krasilnikov, and N.K. Tsenev: Mater. Sci. Eng.,

1991, vol. A137, pp. 35-40.

3. Y. Iwahashi, Z. Horita, M. Nemoto, and T.G. Langdon: Acta Mater.,

1997, vol. 45, pp. 4733-41.

4. J. Wang, Y. Iwahashi, Z. Horita, M. Furukawa, M. Nemoto, R.Z.

Valiev, and T.G. Langdon: Acta Mater., 1996, vol. 44, pp. 2973-82.

5. M. Furukawa, Z. Horita, M. Nemoto, R.Z. Valiev, and T.G. Langdon:

Acta Mater., 1996, vol. 44, pp. 4619-29.

6. M. Furukawa, Y. Iwahashi, Z. Horita, M. Nemoto, N.K. Tsenev, R.Z.

Valiev, and T.G. Langdon: Acta Mater., 1997, vol. 45, pp. 4751-57.

7. M. Furukawa, P.B. Berbon, Z. Horita, M. Nemoto, N.K. Tsenev, R.Z.

Valiev, and T.G. Langdon: Metall. Mater. Trans. A, 1998, vol. 29A,

pp. 169-77.

8. S. Ferrasse, V.M. Segal, K.T. Hartwig, and R.E. Goforth: Metall.

Mater. Trans. A, 1997, vol. 28A, pp. 1047-57.

9. S. Ferrasse, V.M. Segal, K.T. Hartwig, and R.E. Goforth: J. Mater.

Res., 1997, vol. 12, pp. 1253-61.

10. Aluminum: Properties and Physical Metallurgy, J.E. Hatch, ed., ASM,

Metals Park, OH, 1984, pp. 231-32.

11. F.J. Humphreys and M. Hatherly: in Recrystallization and Related

Annealing Phenomena, Pergamon, Oxford, United Kingdom, 1995, p.

333.

12. Y. Iwahashi, Z. Horita, M. Nemoto, and T.G. Langdon: Acta Mater.,

1998, vol. 46, pp. 3317-31.

13. Y. Iwahashi, J. Wang, Z. Horita, M. Nemoto, and T.G. Langdon:

Scripta Mater., 1996, vol. 35, pp. 143-46.

14. Y. Wu and I. Baker: Scripta Mater., 1997, vol. 37, pp. 437-42.

15. Z. Horita, D.J. Smith, M. Furukawa, M. Nemoto, R.Z. Valiev, and

T.G. Langdon: J. Mater. Res., 1996, vol. 11, pp. 1880-90.