An Enhanced Fuzzy Control Strategy for Low-Level Thrusters

in Marine Dynamic Positioning Systems Based on Chaotic

Random Distribution Harmony Search

Defeng Wu

1,2

•

Yuxiang Liao

1

•

Chaodong Hu

1

•

Shuanghe Yu

3

•

Qingyuan Tian

1,2

Received: 22 February 2020 / Revised: 6 October 2020 / Accepted: 13 October 2020

Taiwan Fuzzy Systems Association 2020

Abstract The required control force vector is distributed

by the thrusters in marine dynamic positioning system

(DPS) to obtain the desired thrust and angle of each

thruster. The thrust of the thruster is mapped to the speed of

the thruster, and the low-level thrust controller adjusts the

speed of the thruster to achieve the vessel’s dynamic

position. Based on the previous research, the permanent

magnet synchronous motor (PMSM) is selected as the low-

level driving motor, and it is combined with the propeller

to form the low-level thrusters for the DPS. The fuzzy

control strategy is selected for the PMSM controller design,

and the proposed chaotic random distribution harmony

search (CRDHS) algorithm is used to optimize the fuzzy

controller rules’ weights. The proposed CRDHS employs a

chaotic map for rule weight adaptation in order to prevent

the conventional harmony search to get stuck on local

solutions. By adjusting the weights of each fuzzy rule via

CRDHS, more consistent control performance is achieved.

The required fuzzy output and the fuzzy controller are used

for control of the PMSM. Simulation results show that

under load disturbance, the fuzzy controller based on

CRDHS has better control performance.

Keywords Dynamic positioning Low-level controller

Permanent magnet synchronous motor Fuzzy control

Chaotic random distribution harmony search

1 Introduction

The dynamic positioning system (DPS) has become a

necessary support system for ocean explorations. After the

thrust allocation algorithm in DPS distributes the expected

resultant force and moment to each thruster, each thruster

obtains a command of the desired thrust and then adjusts

the rotational speed of the thruster through the local con-

troller of the thruster to achieve the desired thrust. The

thrusters in DPS are mainly classified into three types,

namely, tunnel thrusters, azimuth thrusters and pod thrus-

ters. Tunnel thrusters and azimuth thrusters are the most

widely used in DPS. As the executing agency of the fixed-

point positioning task of the power system, the accuracy of

thrust generation and the reliability and safety of operation

are related to the survival of the dynamic positioning (DP)

of the ship. This parameter is an important guarantee for

the successful completion of special operations at sea;

therefore, thruster control plays a vital role.

Electric power propulsion has become one of the most

effective ways of promoting various ship types in recent

decades. The use of modern electric propulsion began in

the 1980s. With the development of semiconductor

switching devices in high-power drivers (DC drives and

later AC–AC drives), full-speed control of propellers was

made available to simplify the mechanical structure. At the

same time, with the rapid development of inverter tech-

nology, DC drives are quickly being replaced by AC

drives. In the same period, electric propulsion became the

basic standard for large cruise ships. Icebreakers, cruise

& Defeng Wu

1

School of Marine Engineering, Jimei University,

Xiamen 361021, People’s Republic of China

2

Fujian Provincial Key Laboratory of Naval Architecture and

Ocean Engineering, Xiamen 361021, People’s Republic of

China

3

School of Marine Electrical Engineering, Dalian Maritime

University, Dalian 116026, People’s Republic of China

123

Int. J. Fuzzy Syst.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s40815-020-00989-5

ships, and DP-operated drilling ships all use electric

propulsion [1]. The electric ship includes an energy gen-

eration module, an energy storage module, a power con-

version module, an electric propulsion module, and a ship

service load, wherein the electric propulsion module is an

important component of the electric propulsion ship, which

is performed using an electric motor. The most important

advantage is that naval engineers are no longer constrained

by in-line reduction gears and shaft placement, which

provides potential benefits for replacing the mechanical

coupling between the prime mover, propeller and the grid.

This advantage also reduces fuel consumption, enhances

dynamic performance, increases reliability, reduces main-

tenance costs, and provides for a more flexible ship layout

[2]. There are many choices of electric propulsion ship

propulsion motors, including advanced induction motors,

permanent magnet synchronous motors, high-temperature

superconducting synchronous motors, and superconducting

unipolar DC motors. With their higher power density and

efficiency, these motors allow for more compact and effi-

cient propulsion designs and are therefore often selected as

propulsion motors for electric propulsion vessels. Perma-

nent magnet synchronous motor (PMSM) technology is an

excellent solution for ship direct drive propulsion, which

has significant advantages in terms of size, weight and

power compared to conventional motors. Due to such

advantages as simple design, a reliable and durable motor,

easy maintenance, and low design cost, this technology is

often selected as the low-level driving motor for electric

power-driven ships [3]. Therefore, the PMSM is chosen as

the low-level driving motor and the thrusters are formed

together with the propellers for DPS in this paper, and the

simulation of the low-level thruster control is based on

PMSM as the test object.

Classical proportional integral (PI) control technology is

still popular because of its ease of implementation [4].

However, there are many disturbances and uncertainties in

the actual PMSM system, which may come from internal or

external sources, such as unmodeled dynamics, parameter

changes, and friction and load disturbances. If the PI

control algorithm is adopted, such a linear control method

is susceptible to restriction by these disturbances. There-

fore, using a variety of nonlinear control methods to

improve the control performance of the PMSM control

system under conditions of varying disturbances and

uncertainties has become one of the most important

research topics of experts and scholars around the world.

The control methods for PMSM involved [5–17] include

robust control, sliding-mode control, adaptive control,

backstepping control, model predictive control and fuzzy

control et al. A robust control strategy for PMSM speed

control was developed in Ref. [5, 6]. A nonlinear speed-

control algorithm based on sliding-mode control [7] for the

PMSM was developed in [8]. An adaptive sliding-mode

control unified with disturbance torque observer (DTO)

was proposed and verified in TMS320F28335 platform [9].

Adaptive control was employed and an adaptive speed

regulator for a PMSM was achieved in [10]. Backstepping

controller design technique [11] was applied and back-

stepping wavelet neural network control strategy was

achieved for induction motor drives in [12]. Model pre-

dictive control (MPC) was also used for PMSM drives in

[13]. However, the conventional MPC increased the cal-

culation load. Furthermore, the fuzzy controller was

employed for PMSM speed control widely due to its

advantages [14–17].

From these nonlinear control strategies, fuzzy control is

a kind of control method which is increasingly used in

industrial control. Fuzzy control is not dependent on an

accurate mathematical model of the controlled object and a

change in its parameters. Fuzzy control is a more feasible

way to deal with uncertain problems, and its control per-

formance is better compared with traditional methods in

real time. Fuzzy control can accelerate the response and

improve control precision. As the working environment of

the ship DP propulsion system is complex and changeable,

it is difficult to establish a mathematical model with suf-

ficient accuracy for the control object. Therefore, the

ordinary linear control method is difficult to efficiently deal

with influences caused by a large change in the motor load

and mathematical model, which makes it difficult to meet

the high performance standards required in some working

conditions with high-precision control requirements.

Therefore, fuzzy control is chosen as the control method

for DPS thruster control to meet the control requirements

mentioned above. The accuracy of fuzzy control depends

mainly on input–output domain division, membership

function selection, fuzzy implication operator, fuzzy rea-

soning synthesis operator and establishment of fuzzy

knowledge base. Therefore, the optimization of fuzzy

control generally focuses on the optimization of domain,

membership function, implication and reasoning operators,

and fuzzy knowledge base. Cabrera et al. [18] applies a

genetic algorithm and actual data verification to obtain the

corresponding fuzzy rule base for different road types,

adhesion coefficients and slip amounts and applies this rule

to optimal traction control of motorcycles on roads, which

has been experimentally verified. Xu et al. [19] uses

knowledge of human experts to simplify the rule base and

uses the particle swarm algorithm to fine-tune the fuzzy

controller and apply it to the problem of optimal scheduling

of local expressway ramps. Zong et al. [20] optimizes the

fuzzy membership function to achieve its goal of opti-

mizing the fuzzy controller model and applies it to the

consistent routing of information. In this paper, when the

membership function and fuzzy rules are determined, an

International Journal of Fuzzy Systems

123

appropriate objective function is set. An improved har-

mony search algorithm, namely, chaotic random distribu-

tion harmony search (CRDHS) is proposed to optimize the

weights of each rule in the rule base. Each rule is adjusted

by optimizing the weights. Regulating the output with an

appropriate combination of rules achieves the final output

optimization.

Harmony search is an optimization algorithm based on

the process of music synthesis [20], which imitates a

composer’s improvisation in a musical composition when

he adjusts a set of notes or notes in a specific range. Our

goal is to look at a harmonious combination of sounds from

an aesthetic point of view. The harmony search algorithm

can recognize the high-performance area in the solution

space in a reasonable time, but it is easy to get into trouble

when performing local search for numerical applications.

Researchers are still working hard to improve the fine-

tuning characteristics and improve the convergence speed

of the harmony search algorithm [21]. However, although

the harmony search algorithm maintains a high harmonic

memory consideration probability (HMCR), even though

local search ability is guaranteed, there exists a large

impact on the global search ability of the harmony search

algorithm because global search ability is only guaranteed

by generating new harmonies at random. In response to the

appeal issue, the researchers made some improvement

work and made some more satisfactory progress: for the

defects of the fixed parameters of the harmony search

algorithm, researchers have proposed the concept of vari-

ous dynamic parameters to improve the performance of the

harmony search algorithm [22–24]. Sarkhel et al. [25]

proposes a harmony search algorithm based on anti-learn-

ing strategies. In [21], the harmony search algorithm

interacts with the chaos operator. In this combination,

chaos operators are used to adjust the parameters of the

harmony search algorithm. Based on the improvement of

the harmony search algorithm, the researchers used these

improvement methods in various fields to verify the

effectiveness of the improvement methods in practical use.

Gao et al. [26] performs a differential operation in the

harmony search algorithm and uses a differential harmony

search algorithm for face tracking; a pseudo-consonant

harmony search algorithm is applied to a fractional fuzzy

PID controller for wind energy hybrid power systems.

Among these systems, References [27, 28] used the

improved harmony search algorithm for thrust allocation

optimization of dynamic positioning drilling platforms.

The optimization of the harmony search algorithm and its

application in practical applications has always been a

prime focus of the research.

The main contributions of this study are listed as

follows.

1. A chaotic random distribution harmony search

(CRDHS) algorithm is proposed based on the chaotic

mechanism in this study. The proposed CRDHS can

enhance the global convergence and prevent to stick on

a local solution which makes the solution quality

better.

2. Computational complexity is of great importance to

optimization algorithms. The computational complex-

ity of proposed CRDHS algorithm is almost the same

as conventional harmony search algorithm. Thus, the

proposed CRDHS will not increase the computational

load and this will make the CRDHS application easy.

3. The CRDHS is applied in design of fuzzy controller for

low-level thrusters in DPS. The parameters of fuzzy

controller are obtained via proposed CRDHS and the

control performance is enhanced.

This paper is roughly divided into the following sec-

tions: The second section introduces the structure of the

ship’s dynamic positioning, propulsion system and the

mathematical model of the permanent magnet synchronous

motor; the third section introduces the harmony search

algorithm, and we propose an improved harmony search

algorithm, named the chaotic random distribution harmony

search algorithm, which is the fuzzy control strategy

applied to the harmony search algorithm; the fourth part is

based on the simulation results of the third part, used to

verify the feasibility of the proposed control strategy; the

final section presents our study’s conclusions and future

work.

2 Dynamic Positioning Propulsion System

2.1 Dynamic Positioning Propulsion Sy stem

When the ship DPS is in positioning mode, the positioning

command can be given by starting DP mode or by oper-

ating the joystick. At this point, after the thrust system

receives the thrust command from the control system [29],

it uses the thrust allocation algorithm to calculate the thrust

size and direction instructions that each thruster unit needs

to achieve [30, 31]. Furthermore, each local thruster control

unit obtains the shaft rotational speed from the required

thrust map based on the static map. Finally, the thrust

coefficient is determined based on the value of the forward

speed, and the general split is divided into two cases to

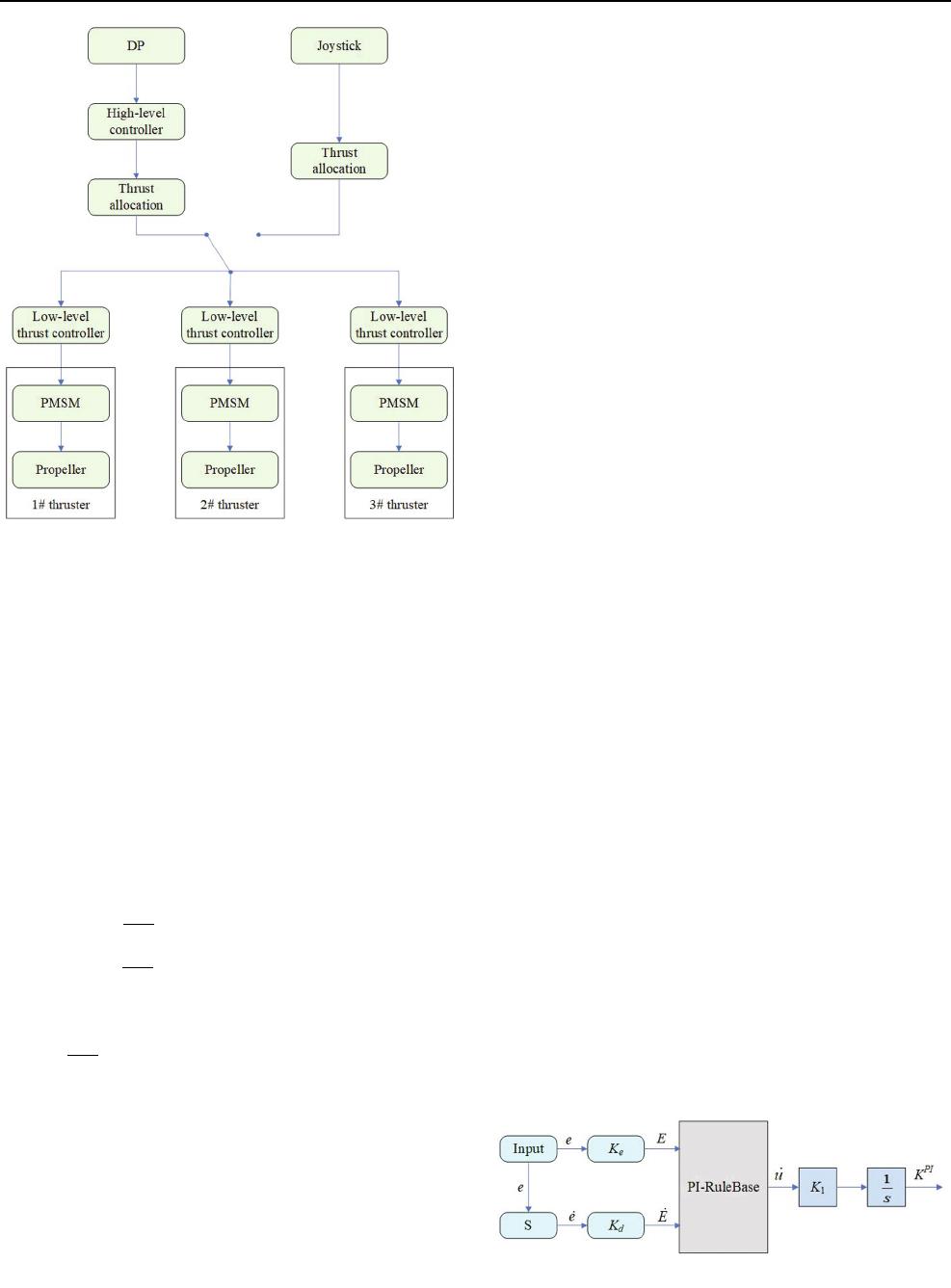

obtain the corresponding values. Figure 1 shows the block

diagram of the thrust controller.

D. Wu, et al.: An Enhanced Fuzzy Control Strategy for Low-Level Thrusters…

123

2.2 Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor

Mathematical Model

As stated in the introduction, the PMSM design is widely

used in the propulsion system for DPS as its low-level

thruster. This study also adopts the PMSM as the simula-

tion object to verify the feasibility of the fuzzy control

optimization strategy; therefore, in this part, the mathe-

matical model of the PMSM is briefly introduced.

In general, the dynamic performance of a permanent

magnet synchronous motor can be represented by the fol-

lowing formula based on the rotor d - q coordinate

system:

V

d

¼ R

S

I

d

þ

du

d

dt

p

n

x

r

u

q

V

q

¼ R

S

I

q

þ

du

q

dt

p

n

x

r

u

d

8

>

<

>

:

: ð1Þ

The mechanical equation is as follows:

T

em

¼ J

dx

r

dt

þ f

m

x

r

þ T

L

: ð2Þ

The electromagnetic torque equation is as follows:

T

em

¼ p

n

L

d

L

q

I

d

þ u

m

I

q

: ð3Þ

The meaning of each parameter is as follows: u

d

¼

L

d

I

d

þ u

m

and u

q

¼ L

q

I

q

are the total flux linkages along

the d and q-axes, respectively.

V

d

; V

q

represent d- and q-axis stator voltage, respec-

tively; I

d

; I

q

represent d and q-axis stator current,

respectively; L

d

; L

q

represent d- and q-axis stator induc-

tance, respectively; R

S

represents the stator resistance; x

r

represents the rotational frequency of the rotor in terms of

angular frequency; T

em

; T

L

are the electromagnetic torque

and load torque, respectively; u

m

is the rotor flux linkage to

the stator; J is the moment of inertia of the motor and the

load; f

m

is the motor friction coefficient; P

n

is the pole pair

number.

3 Fuzzy Control Strategy

3.1 Conventional Fuzzy Control

Professor Zadeh first proposed the concept of fuzzy set

theory and applied in a real case [32]. Fuzzy control

attempts to design controllers for systems that are struc-

turally difficult to model. Since then, fuzzy control has

become one of the most active and fruitful research areas in

the theory of fuzzy sets, it has been applied in industrial

processes, and the theory itself has many practical appli-

cations [33]. Similar to non-ambiguous 2-D and 3-D con-

trol, conventional fuzzy control also has 2-D and 3-D

control modes. Non-ambiguous two-dimensional control

methods are divided into two types, one is a proportional-

integral controller, the PI controller; the other is a pro-

portional-derivative controller, the PD controller. The PI

controller mathematical formula is as follows:

U

PI

¼ K

p

e þ K

i

Z

edt¼ K

p

Z

_

e þ T

i

eðÞdt: ð4Þ

The PD controller mathematical formula is as follows:

U

PD

¼ K

p

e þ K

d

_

e ¼ K

p

e þ T

d

_

eðÞ; ð5Þ

where e is the error,

_

e is the differential of the error,

T

i

¼ K

i

K

p

,T

d

¼ K

d

=

K

P

, if the variable e and

_

e are fuzzy

variables which form a fuzzy-PI controller and a fuzzy-

differential controller. In the continuous two-dimensional

fuzzy controller design, it is generally divided into a fuzzy-

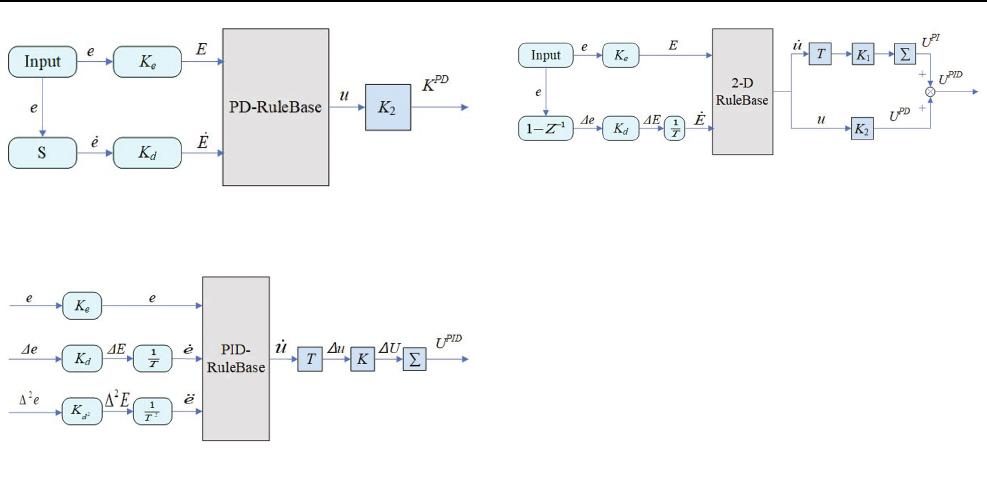

PI controller and fuzzy-PD controller, as shown in Fig. 2

and Fig. 3, respectively:

K

e

and K

d

are the input scaling gain parameters, which

are generally determined by the actual input and the

required domain of fuzzy control. K

1

and K

2

are the output

Fig. 1 Block diagram of the thrust controller

Fig. 2 Fuzzy-PI dual-input single-output controller architecture

International Journal of Fuzzy Systems

123

scaling gain parameters, generally required by the actual

output and fuzzy output on the domain decision. The main

difference between the two lies in the selection of output

gain and fuzzy rules. The fuzzy-integral controller includes

an integral operation in the output. The output control

quantity is

_

u, which can be called the speed control

quantity and fuzzy-derivative. The output of the controller

is u; therefore, we should also pay attention to the differ-

ence between the two when designing fuzzy rules.

Fuzzy-PI controllers have inherently higher transient

response performance to higher-order processes due to

their internal integral operations, and fuzzy-PD controllers

have large steady-state errors. Considering the disadvan-

tages of these two control approaches, the fuzzy-PID

controller is chosen in this study. Since the conventional

fuzzy-PID controller is a three-input single-output fuzzy

controller, as shown in Fig. 4. For fuzzy control, the rules

increase with the number of inputs. The increment and

exponential growth are unfavorable for the optimization of

fuzzy control; thus, we have simplified the three-input

fuzzy-PID controller by sharing the PD and PI rule bases in

this study. The two-input two-output fuzzy controller

[34, 35] is simplified to achieve the controller as shown in

Fig. 4 and the simplified fuzzy controller structure is

shown in Fig. 5. This simplification can reduce the three-

input fuzzy controller to a dual-input fuzzy controller,

effectively reducing the complexity of the rules, and

facilitating subsequent optimization of the fuzzy controller.

3.2 Improved Harmony Search Algorithm

3.2.1 Harmony Search Algorithm

The harmony search (HS) algorithm is a meta-heuristic

algorithm based on music creation proposed in [20]. The

music author creates a beautiful harmonic memory based

on his own creative experience. From this, he records a

new beautiful harmony through random performance. This

cycle can result in a beautiful harmonic library. The HS

algorithm has been applied to many practical problems,

including some classical optimization problems, such as

truss design to obtain minimum structural quality, business

travel problems, and water supply network design. In

addition, the experimental data are used to reflect the

superiority of the harmony search algorithm in solving

these problems. At the same time, researchers worldwide

have investigated approaches to improve HS [21–24].

The optimization process of the harmony search algo-

rithm can be roughly divided into five parts. The steps are

as follows:

Step 1: Determine the optimization goal and algorithm

parameters.

Step 2: Initialize the harmony memory.

Step 3: Select harmony from the harmony library or

create a new solution by random playing.

Step 4: Evaluate the worst solution from the new

solution and harmony memory. If the former is better

than the latter, replace it. Otherwise, leave it as it is.

Step 5: Repeat steps 3 and 4 until the loop condition is

satisfied.

It can be seen that the process of the harmony search

algorithm is relatively simple. The new solution selects

components from the harmony memory to ensure local

search ability of the algorithm and plays randomly to

compose a new solution, thereby ensuring global search

ability of the algorithm. The entire algorithmic process of

HS has been reviewed in this study, and the setting of its

Fig. 3 Fuzzy-PD dual-input single-output controller architecture

Fig. 4 Fuzzy-PID three-input single-output controller architecture

Fig. 5 Simplified Fuzzy-PID three-input single-output controller

architecture

D. Wu, et al.: An Enhanced Fuzzy Control Strategy for Low-Level Thrusters…

123

parameters for the specific case of the HS algorithm is also

investigated. The HS algorithm is given in more detailed

procedure when considering specific problem in the fol-

lowing steps:

Step 1: Assume that our optimization problem is

specified as follows:

Min fxðÞx

i

2 X

i

; i ¼ 1; 2; ...; N

jfg

; ð6Þ

where f(x) is an objective function; x denotes the set of

each decision variable x

i

; N represents the number of

decision variables, X

i

denotes a set of possible values for

each decision variable and x

i

2½x

l

i

; x

h

i

where x

l

i

and x

h

i

upper are the lower and upper boundaries for each

decision variable, respectively.

At the same time, the parameters needed for optimiza-

tion of the harmony search algorithm need to be set,

including the harmony memory size (HMS), harmony

memory consideration probability (HMCR), pitch

adjustment probability (PAR), and the maximum num-

ber of iterations N. From these parameters, the harmony

memory consideration probability and pitch adjustment

probability are two goals that are often optimized as

parameters.

Step 2: Initialize the harmony memory. The harmony

memory can be thought of as a matrix with the harmony

memory size (HMS) as the number of rows, and the

dimension (N) of each solution is the number of

columns. Assuming that x is the solution, then the

harmony memory can use the following matrix to reflect:

HM ¼

x

1

1

x

1

2

x

1

3

x

1

D

fx

1

ðÞ

x

2

1

x

2

2

x

2

3

x

2

D

fx

2

ðÞ

x

3

1

x

3

2

x

3

3

x

3

D

fx

3

ðÞ

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

x

HMS

1

x

HMS

2

x

HMS

3

x

HMS

D

fx

HMS

ðÞ

2

6

6

6

6

6

6

4

3

7

7

7

7

7

7

5

:

ð7Þ

The solutions in the harmonic memory are arranged

from small to large according to its fitness value,

meaning that the first set of solutions in the harmonic

memory are the optimal solution and the last set of

solutions in the harmonic memory are the worst solution

to this harmony memory.

Step 3: Generating a new solution from the harmony

memory, select the components in the harmony memory

based on the parameters and the harmony memory

consideration probability (HMCR), or generate new

solution components randomly, as shown in the follow-

ing formula:

x

New

i

:

x

New

i

2 x

1

i

; x

2

i

; ...; x

HMS

i

t HMCR

x

r

i

t [ HMCR

; ð8Þ

where t represents a random number between 0 and 1,

if the new solution component of t B HMCR is ran-

domly selected in the harmony memory, instead it is

generated in the component definition field. After the

new solution is generated, the harmony search algorithm

also needs to fine-tune the new solution with the prob-

ability of PAR, as shown in the following formula:

Pitch Operation for X

New

i

:

Yes if rand 0; 1ðÞPAR

No if rand 0; 1ðÞ[ PAR

:

ð9Þ

Step 4: Evaluate the worst solution in harmony memory

with a new solution and update the harmony memory.

Step 5: Repeat steps 3, 4 until the loop condition is met.

3.2.2 Chaotic Random Distribution Har mony Search

Algorithm

For the HS algorithm in the case of high HMCR, the

diversity of the harmony memory only depends on random

generation. Two improvements are proposed in this study,

which distinguish it from the conventional HS algorithm.

We are not only focusing on adjusting parameters in the HS

algorithm dynamically. Instead, the harmony memory is

initialized based on chaotic operators and the values

between the solution components in the harmonic memory

are randomly assigned with a certain probability after the

harmonic memory is formed. We define the proposed

algorithm in this study as chaotic random distribution

harmony search algorithm (CRDHS).

There are many kinds of chaotic operators, including

logical mapping, tent mapping, sine iteration, and Gaussian

mapping [21]. In this paper, we use logical mapping as the

chaos operator. The value r [ (0, 1) is used as a random

parameter initialized by the harmony memory, where the

logical mapping is as follows:

X

nþ1

¼ aX

n

1 X

n

ðÞ; ð10Þ

a is set to 4 in this article [21], and X

n

is used as the

chaotic number for the iteration. Obviously when X

0

[ [0,

1] and X

0

[ {0.0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1.0}, X

n

[ [0, 1]. We use

X

n

for the initialization of each solution to be evaluated in

International Journal of Fuzzy Systems

123

our harmony memory, as shown in the following formula,

where we define X

n

as the variable r:

x

i

¼ X

i

l

þ r X

i

h

X

i

l

; i ¼ 1; 2; ; N: ð11Þ

In Eq. (11), r represents a random number between (0,

1) calculated by the chaotic operator, and x represents a

solution in the harmonic memory. X

i

l

,X

i

h

represent the

lower and upper limit of the value range of the i dimension

in each solution, respectively. In addition, in order to

overcome the deficiencies of the partial search ability of

the harmony search algorithm, we use larger HMCR and

PAR to ensure the local search ability of the harmony

search algorithm. However, in the case of larger HMCR,

the probability that the harmonic memory acquires new

solution components in each iteration is smaller, which

means that the diversity of the harmony memory is com-

pletely dependent on low probability of random generation,

which will have a negative impact on the search speed of

the algorithm. This effect often leads to a large number of

iterations to ensure completion of the search results. In this

paper, we propose a random distribution operation with the

variable Assign as the probability, by adjusting the

harmony memory in one iteration. The value of each

solution component increases its diversity, which in theory

will improve the search ability and speed of the algorithm.

The specific operation is as follows:

x

i

¼ x

i

þ r

c

x

c

x

c

¼ x

c

1 r

c

ðÞ

(

; c ¼ 1; 2; ...; N; i ¼ 1; 2; ...; N:

ð12Þ

In Eq. (12), c represents the index of the arbitrarily

chosen component in 1, 2,…, N. The index represents the

current component and the other components in the solu-

tion are randomly distributed to the data volume. If x

i

[X

i

h

occurs during distribution, the value of X

i

h

is assigned to x

i

.

Of course, this random distribution operation will only be

performed if the parameter Assign is satisfied, which can

guarantee the originality of the harmony memory and

increase its diversity in one iteration. This attribute is

conducive to the improvement of its algorithm search

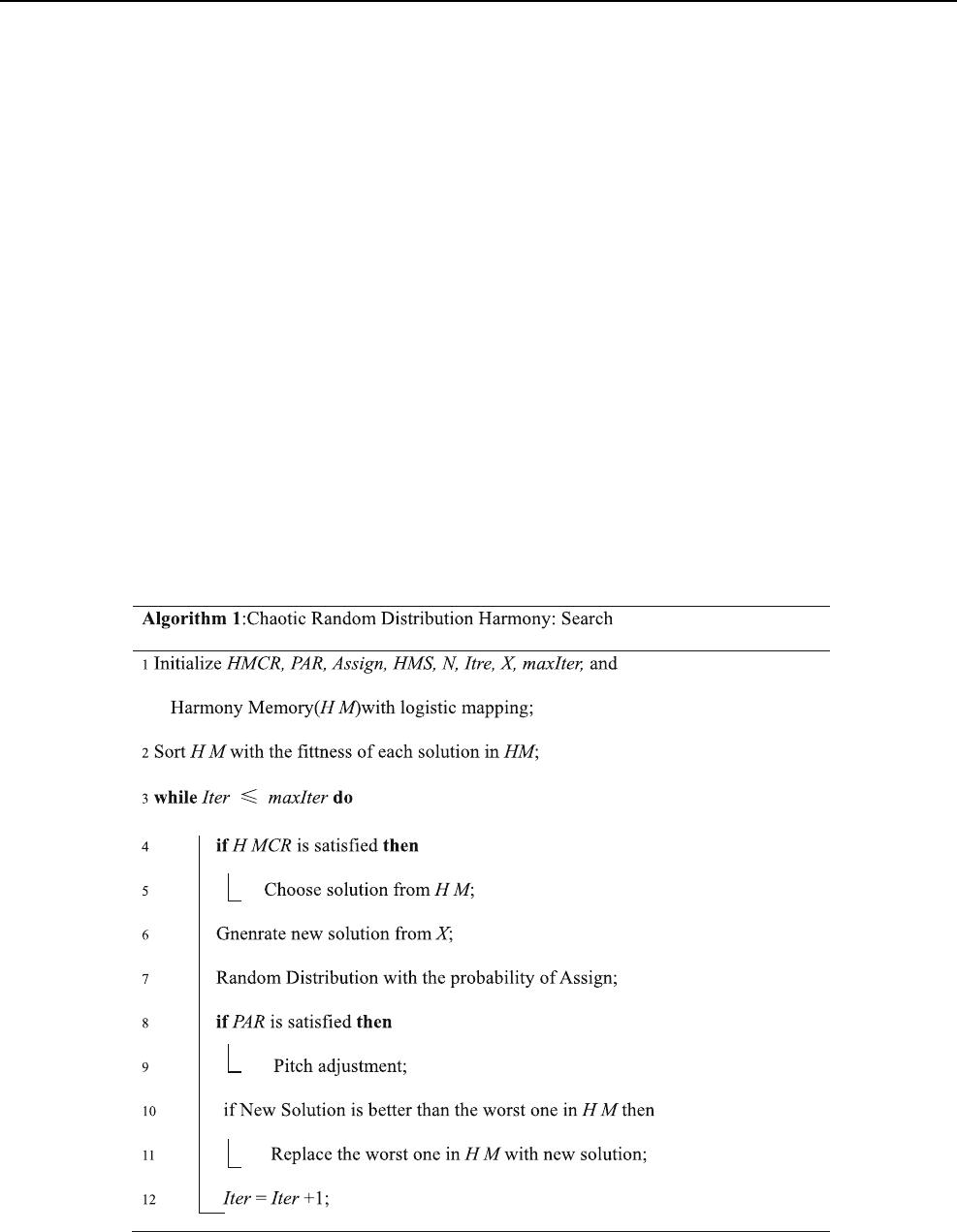

capabilities. The pseudocode for this improved algorithm is

shown in Algorithm 1.

D. Wu, et al.: An Enhanced Fuzzy Control Strategy for Low-Level Thrusters…

123

The computational complexity of Algorithm 1 is ana-

lyzed as follows:

Step 1: Initialization of the harmony memory, we set the

size of the harmony memory to HMS. The dimension of

each solution is D, so the complexity of the initialization

time of the harmony memory is O(HMS

*

D).

Step 2: Calculate the fitness value of each of the

harmony memory entries and select the worst solution

among them as the solution to be compared against. The

time complexity is O(HMS).

Step 3: The new solution is selected from the harmony

memory. The operation time complexity is O(1); if the

new solution is randomly generated, the time complexity

is O(N), so the time complexity of this step is O(N).

Step 4: Randomly assign the generated solution with a

time complexity of O(N), and the time complexity of

fine-tuning is also O(N), which means the total time

complexity is O(2 N).

Step 5: Compare the generated new solution with the

worst solution in the harmony memory and decide

whether to update the harmony memory. The time

complexity is O(1).

In conclusion, the iteration number of this algorithm is

set to maxIter; thus, the complexity of this algorithm is

O(maxIter

*

(HMS ? 3

*

N ? 1)).

3.3 Fuzzy Control Strat egy Based on Chaotic

Random Distribution Harmony Search

Algorithm

For the simplified fuzzy controller input and output struc-

ture seen in Fig. 5, we employ it in the control of the low-

level thruster in which the PMSM acts as the driving motor

for the DPS. At the same time, in Fig. 5 we can see that the

selection of some parameters and determination of the

control effect of the fuzzy controller will have a certain

impact; therefore, the CRDHS algorithm is used to opti-

mize the parameters of the fuzzy controller.

In this design, our optimization method selects output

scaling gain factors K

1

and K

2

and the weights of each rule

of the two-input dual-output fuzzy model. By adjusting the

weight of each rule, the final fuzzy output can be

determined.

First, we select the fuzzy domain of the input parameters

E and E

˙

. We set the speed change to [- 600, 600]

according to the actual situation and job requirements, and

the value range of the speed change rate is [- 15,000,

15000], the fuzzy scope of the input variables, e and e

˙

are

both [- 1,1], so K

e

= 1/600, K

d

= 1/15,000 is used as the

input scaling factor. For input e and e

˙

, and the outputs

u and u

˙

, we divide them into fuzzy universes. The selected

membership function is the triangle membership function,

as shown in Figs. 6 and 7.

For fuzzy control, fuzzy rules reflect the fuzzy rela-

tionship between the input and output as a reference; it

plays an important role for the control effect, and the

PMSM is chosen as the control object in this study. In

addition, a fuzzy rules table is chosen as a fuzzy knowledge

base as shown in Table 1 [34].

After the scope of the input–output domain and the

fuzzy rules are determined, we use algorithm 1 to optimize

the weight of each rule and the output scaling factors. The

value range of the rule weight is [0, 1], and the value range

of the output scaling factors K

1

and K

2

is selected as [0,

10]. For simplification, we chose to use 10 times the ran-

dom number in the range of [0, 1] for model simulation in

the algorithm operation such that the range of values of the

parameters to be optimized is consistent, which is benefi-

cial to our optimization work.

The fuzzy control strategy based on CRDHS is specifi-

cally divided into the following steps:

Step 1: Initialize rule weights and output scaling factors.

The number of rules selected in this design is 5 9 7, or

35-rule weights, plus two-output scaling factors, K

1

and

K

2

, for a total 37 parameters (refer to 3.2.2). In other

words, the dimension N for solution x is 37, and the

Fig. 6 Input membership function curve

International Journal of Fuzzy Systems

123

range of values for each solution X is [0, 1]. It is

specifically shown by the following formula:

x

i

¼ x

1

; x

2

; ; x

j

; K

1

=

10; K

2

=

10

; ð13Þ

where x

j

, j =1,2,… 35 represents the weight of each

rule, and x

i

represents a solution in the harmony mem-

ory.

Our goal is to be able to find the appropriate combination

of parameters such that the fuzzy controller mentioned in

this article will achieve better control results. Therefore,

it is necessary to determine a standard which can eval-

uate the performance of the controller. ITAE (integration

of the time multiplied by the error absolute value), ISE

(squared error integral) and IAE (absolute error integral)

are three indicators commonly used to judge the per-

formance of a control system. Their mathematical

expressions are

ITAE ¼

Z

s

0

e

w

tðÞ

jj

tdt; ð14Þ

ISE ¼

Z

s

0

e

2

w

tðÞdt; ð15Þ

IAE ¼

Z

s

0

e

w

tðÞdt: ð16Þ

In this paper, we use ITAE as the performance index to

evaluate the fuzzy controller, and it is also the objective

function value of the chaotic random distribution har-

mony search algorithm.

Step 2: The initial harmony memory of x is sorted

according to the ITAE indicator and used as the input

harmony memory HM of the algorithm. Run Algorithm

1 to generate the ITAE value after the model has been

run completely. The objective function determines the

merits and demerits of the worst solution in comparing

the new solution and the harmonic memory.

Step 3: After algorithm 1 satisfies the loop requirement,

we record the resulting harmonic memory and assign

each component of the optimal solution x

best

to the rule

weight in the fuzzy controller and output scaling factors.

The comparisons are made among original fuzzy con-

troller, a classic PID controller, and an optimal fuzzy

controller optimized by HS and CRDHS to verify the

effectiveness of the fuzzy controller optimization strat-

egy. The specific experimental verification will be

introduced in detail in the fourth part.

Remark 1 The ITAE is chosen as the objective function. It

is very difficult to determine the type of the chosen

objective function. The deterministic annealing algorithms

such as Refs [36, 37] cannot be used in the proposed

method. Thus, the proposed CRDHS in this study is

employed to find the optimal solutions for the enhanced

fuzzy controller of the low-level thruster.

Fig. 7 Output membership function graph

Table 1 Output fuzzy rules table

u

_u

e

NB NM NS EZ PS PM PB

_

e NB B,Z B,B S,M M,B S,M B,B B,Z

NS B,Z M,S M,B S,B M,B M,S B,Z

EZ B,Z M,S B,M Z,B B,M M,S B,Z

PS B,Z S,S M,M M,B M,M S,S B,Z

PB B,Z M,M B,B B,B B,B M,M B,Z

D. Wu, et al.: An Enhanced Fuzzy Control Strategy for Low-Level Thrusters…

123

Remark 2 The designed CRDHS-based fuzzy controller

for low-level thruster receives the reference control com-

mand from high-level DPS controller [29, 38–40] and

thrust allocation module [30]. How much information

about the state of the DPS is needed depends on the high-

level controller. Moreover, it should be pointed out that the

proposed controller in this study also has some limitations,

such as offline training and speed signal feedback.

4 Simulation Results

In this section, five different controllers are employed to

control the PMSM, which are, respectively, named the PID

controller, sliding-mode controller, fuzzy-PID controller,

HS-Fuzzy PID controller and CRDHS-Fuzzy PID con-

troller. The step, rectangle and sine signals are chosen to

test the tracking speed performance. The three parameters

of the PID controller are set identically as K

p

= 0.106,

K

i

= 4.223, and K

d

= 0.0008. It should be noted that the

simulation sampling time is set to 5e-06 s, and the model

total running time is 0.1 s. The parameters used by Algo-

rithm 1 and the parameters of the PMSM are shown in

Tables 2, 3.

Case 1: Step signal-tracking performances.

Figure 8 shows the speed-tracking response curves of

different controllers under step signals, and the middle

part shows a partial enlarged view of the curves, which is

convenient for us to analyze. The results from Fig. 8

show the step-tracking performances of these five con-

trollers under the condition of no-load. The reference

speed is set to 600 n/min. It can be also seen from Fig. 8

that PID controller and SMC controller have higher

overshoot and longer response time. Fuzzy-PID and HS-

Fuzzy controllers have relatively larger overshoot and

chattering. The CRDHS-Fuzzy controller can quickly

reach the desired speed without overshooting after being

optimized by CRDHS. It has higher control accuracy and

control efficiency compared with fuzzy-PID algorithm

and HS-Fuzzy algorithm. The speed deviation results

shown in Fig. 9 demonstrated that the CRDHS-based

fuzzy controller can make the speed deviation converge

to a small value very quickly among five controllers.

Case 2: Rectangle signal-tracking performances.

Considering the ship speed regulation tests for DPS, we

also carried out relevant simulation verification for the

changing rectangular wave: the signal is changed once

every 0.02 s from the initial setting of 600 to the

transition of 300, 500 and finally remaining at 400. The

disturbance signal is chosen as a repeated discrete time

series with amplitudes [0, 0, 10, 15, 8] and each

amplitude lasts 5:0 10

6

s. The load torque T

L

is

chosen as follows:

T

L

¼

00s t\0:03s

2 sin 300tðÞ0:03s t 0:1s

: ð17Þ

From Fig. 10, we can see the continuous rectangular

wave signal when the signal is in the rising phase.

Because the fuzzy controller can reach steady state

quickly, it can reach stable speed in a short time, while

the PID and SMC controller enter steady state slowly,

which are unfavorable to the control of the system in the

case of rapid speed change. The fuzzy controller, after

being optimized by CRDHS, can reduce the steady-state

error and overshoot effectively and has better control

precision than the initial state and the fuzzy controller is

optimized only by the HS algorithm; however, it should

be pointed out that when the input is changed from a

large step to a small input, the fuzzy controller will

produce larger oscillations. Compared to the PID con-

trol, it does not produce overshooting.

Due to the load, the PID controller and the SMC con-

troller will fluctuate with the change of the load after

0.03 s. It can be seen from Fig. 10 there is a downward

Table 2 Parameters of the chaotic random distribution harmony

search algorithm

Name Symbol Value

Harmony memory size HMS 40

Harmony memory consideration probability HMCR 0.9

Pitch adjusting probability PAR 0.7

Bandwidth l 0.2

Random distribution probability Assign 0.6

Dimension of solution N 37

Maximum iteration Maxiter 1000

Range of solution X [0,1]

Parameter of logistic mapping a 4

Table 3 Parameters of the permanent magnet synchronous motor

Name (unit) Symbol Value

Rated voltage (V) U 380

Rated power (kW) P 2

Stator winding resistance (X) R

s

2.8757

Moment of inertia (kg.m

2

) J 0.8e-03

D-axis winding self-inductance (H) L

d

8.5e-03

Q-axis winding self-inductance (H) L

q

8.5e-03

Rotor field magnetic flux (Wb) W

f

0.175

Number of pole pairs P

n

4

International Journal of Fuzzy Systems

123