Performance metrics for Spanish investment funds

Luis Ferruz

*

, Christian Pedersen and Jose

´

L. Sarto

*

Department of Accounting and Finance, Faculty of Economics and Business Studies,

University of Zaragoza, C/ Gran Vı

´

a 2, Zaragoza 50005, Spain.

E-mail: [email protected]

Received (in revised form): 16th October, 2006

Luis Ferruz is Full Professor in finance and supervisor of the research group GIECOFIN in the Faculty of Economics

and Business Studies at the University of Zaragoza, Spain.

Christian Pedersen is Director in Finance and Risk Management in Mercer, Oliver, Wyman. He holds a PhD on Risk

Measurement in Finance from Cambridge University.

Jose

´

L. Sarto is Full Professor in finance in the Faculty of Economics and Business Studies at the University of

Zaragoza, Spain.

Practical applications

This paper is useful for investors and managers of investment funds since it tries to identify the true

performance of these portfolios. The empirical results obtained in the Spanish equity fund market

provide evidence for the incorrect performance valuations when classical indexes are considered.

These problems are caused by: 1) the asymmetric return distributions; 2) the negative return premia.

On this subject, the application of the original measures proposed in this work leads to coherent

performance rankings. So, these rankings suppose very useful information for fund investors to value

the management quality of each fund and for fund managers to know their relative position with

respect to the rest of the market.

Abstract

The aim of this study is to examine the most

appropriate way to capture the true performance of

Spanish equity funds, considering that almost all have

significantly asymmetric return distributions over the

time period studied. We apply alternative risk

measures, such as semi-standard deviation and absolute

deviation and test if the associated performance

measures provide markedly different rankings from the

classic indices. We find that one subset of funds

analysed displays negative return premia, and make an

additional adjustment to the suggested performance

metrics. Overall when comparing the rankings, we see

strong evidence that — despite the strong asymmetry in

returns — the non-traditional performance metrics do

not differ markedly from the traditional measurements.

This would point to the Spanish equity market

behaving more like more mature and liquid markets,

and hence being amenable to the application of classic

performance and investment management tools.

Derivatives Use, Trading & Regulation (2006) 12,

219–227. doi:10.1057/palgrave.dutr.1850043

Keywords: asymmetric return

distributions; Spanish equity funds; performance

measures

Derivatives Use, Trading & Regulation Volume 12 Number 3 2006 219

www.palgrave-journals.com/dutr

Derivatives Use,

Trading & Regulation,

Vol. 12 No. 3, 2006,

pp. 219–227

r 2006 Palgrave

Macmillan Ltd

1357-0927/06 $30.00

INTRODUCTION AND AIMS

Investment funds have been one of the most

important recent phenomena in Spanish

financial markets. The growth of the assets under

management by Spanish funds have been one of

the biggest in Europe for the past 15 years, with

a compounded annual rate of growth greater

than 25 per cent. In all, 250bn euros are

currently managed by approximately 2,600

Spanish investing funds.

Investment funds are now the third most

important investment alternative in Spanish

home portfolios, ahead of other products such as

pension funds and life insurances. The average

assets managed by each Spanish fund are,

however, still one of the lowest in the European

Union, reporting a market map where a small

number of large funds coexist with a vast

majority of small funds. The overall picture

points to a set of vehicles reflecting illiquidity

and ‘youth’ — often leading to strong

asymmetric return distributions.

In this study, we examine the degree of

asymmetry of the returns of these funds and then

evaluate different metrics for capturing their

performance. To determine the performance

values for each fund, we initially consider three

of the indices most commonly implemented in

the financial literature, these being Sharpe

Ratio

1

, Treynor’s Index

2

and Jensen’s Alpha

3

,

while taking into account the total risk of each

portfolio and its systematic risk.

In line with studies by Damant et al.,

4

Eftekhari et al.,

5

Konno and Shirakawa,

6

Okunev

7

and Pedersen and Satchell,

8,9

using

variance, and therefore standard deviation, to

measure the total risk in portfolios was not the

most suitable method when the historical return

distributions of said portfolios display problems

of asymmetry. This is supported by Sortino and

Price,

10

who defend the use of other alternative

risk measures such as semi-standard deviation

and propose alternative ratios for performance

— this was taken further in Eftekhari et al.

5

and

Pedersen and Satchell,

9

who examined such

alternative metrics in more detail. Hence, these

are also tested to see if different from the

traditional performance metrics.

Such alternative measures have also appeared in

the works of Damant and Satchell,

11

Hwang and

Pedersen,

12

Eftekhari and Satchell

13

and Pedersen.

14

Recent studies focused on the application

of asymmetric risk measure are those conducted by

Ang et al.,

15

Hyung and De Vries,

16

Campbell and

Kraeussl,

17

Cheng,

18

Gu,

19

Post and Van Vliet

20

and

Morton et al.

21

Our preliminary examinations also reveal that

a subset of those portfolios considered display a

negative return premium in comparison to the

risk-free assets considered. Hence, we apply

complementary measurements of performance

based on studies conducted by Ferruz et al.

22

and

Ferruz and Sarto.

23,24

Finally, we examine the levels of correlation

existing among all the performance indices taken

into consideration to opine on whether moving

to the less traditional metrics is justified

empirically as well as theoretically — that is we

will see whether rankings of real fund

performance changes significantly.

The fundamentally differential elements of

this work are its focus on a relatively infrequently

analysed market, as is the case with the Spanish

market, and the degree to which Spanish

investment funds display problems with

asymmetry as regards their returns distributions

— which, as far as we are aware, has not been

analysed previously for the Spanish market. It

is also the first time that alternative measures

to determine levels of performance has been

220 Ferruz, Pedersen and Sarto

applied to Spanish data using the methodologies

of Hwang and Pedersen,

25

Estrada

26

and

Eftekhari and Satchell.

13

Inthefollowingsectionweshallanalysethe

characteristics of the database used. The third part

of this study develops the empirical analysis and

we reserve the final section for our conclusions.

THE DATABASE

We analyse 85 Spanish equity funds, which have

the Spanish domestic market as the principal

investment objective. The time-frame for the

study spans from July 1994 to December 2004,

inclusive. The reason for these funds being chosen

is due exclusively to the fact that they represent

the entire population of funds to survive the

aforementioned timescale. We note that this will

in fact understate the asymmetry in returns of

Spanish funds, since those which have failed

would exhibit higher skewness. Nonetheless,

we consider this the most appropriate data upon

which to base our investigations. Our dataset is

biweekly returns from this period.

Asymmetry of return distributions

We have used the skewness coefficient of Fisher

below to test for skewness in the data.

a

3

¼

P

n

t¼1

R

t

EðRÞ

3

,

n

s

3

InTableA1(inAppendixA),wehaveshownthe

asymmetry coefficients corresponding to the

biweekly return distributions of each investment

fund. In this table, we find an identification

number for each fund and the level of significance

of asymmetry presented by each portfolio. In this

respect, the level of significance is 1 per cent in 66

funds and 5 per cent in 74 funds, a circumstance

that demonstrates the generalized nature of this

problem. This problem of asymmetry in the

Spanish Market can be due to the youth of the

market because the investment funds have

experienced high growth only in the last 15 years,

which is a short period of time comparing to

more mature markets like the US or UK.

Negative return premia

Studies by Ferruz et al.

22.

and Ferruz and Sarto

23,24

demonstrate the problems that can arise when

the average historical return of portfolios taken

into consideration is below the level of risk-free

assets. In this respect, they demonstrate that

indices such as Sharpe or Treynor do not

function correctly when faced with variations in

the level of risk in the portfolio.

Specifically, the aforementioned authors offer

an alternative measure S

p

(1) of performance to

Sharpe’s Ratio which, while maintaining the

nature of the original index, considers the return

premium in relative terms.

S

p

ð1Þ¼

E

p

=R

f

s

p

Table A2 (in Appendix A) displays the average

biweekly return values of each portfolio in

addition to their standard deviation and the level

of systematic risk using the b coefficient applied

in correlation with the Madrid Stock Exchange

General Index (IGBM). There are 20 funds that

display a biweekly average return of less than

0.13 per cent corresponding to the riskfree assets

considered, Treasury Repos with overnight

securities. Hence, we make the corrections

above where this is a problem.

ANALYSIS OF PERFORMANCE

MEASURES

Hence, as mentioned earlier, the traditional

indices of Sharpe, Treynor and Jensen are taken

Performance metrics for Spanish investment funds 221

into consideration in this study. But given the

characteristics of the database outlined above, we

supplement these with semi-standard deviation

and absolute deviation (to capture asymmetry).

Additionally, both these ‘new’ metrics and the

Sharpe Ratio with the above adjustments in

consideration of the return premium in a relative

sense as opposed to in absolute terms. Hence, we

have six metrics tested in all.

Specifically, in accordance with these

considerations, in addition to the S

p

(1) index, we

propose two alternative indices to the Sharpe

Ratio. The first of these is expressed as follows:

Pð1Þ¼

E

p

=R

f

SSD

p

where E

p

represents the average return on

portfolio p; R

f

indicates the average return on

the risk-free asset; SSD

p

is the semi-standard

deviation of the return on portfolio p.

This index is therefore similar to Sortino’s

index, although the return premium is expressed

in relative terms. The semi-standard deviation is

calculated as follows:

SSD

p

¼

1

n

X

n

t¼1

ðmin½0; R

pt

E

p

Þ

2

"#

1=2

And the second measure is:

Pð2Þ¼

E

p

=R

f

AD

p

where AD

p

indicates the absolute deviation of

the returns on portfolio p, which would be

calculated as follows:

AD

p

¼ E½jR

p

E

p

j

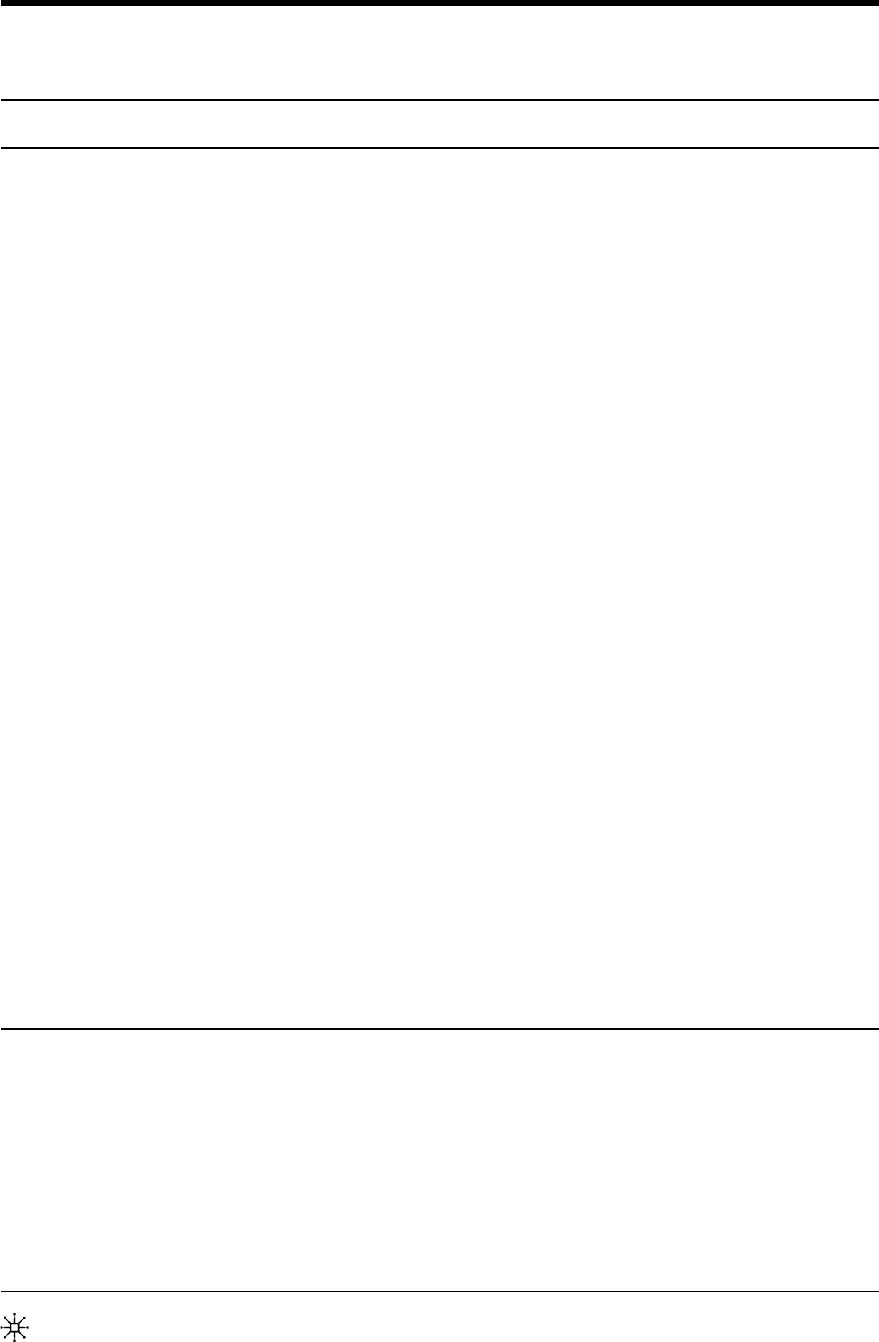

The results of applying the aforementioned indices

are illustrated in Tables A3 and A4, where we

display the funds corresponding to the best quartile

from applying Sharpe, Treynor and Jensen’s indices

in Table A3 and for the alternative indices S

p

(1),

P(1) and P(2) in Table A4. The strong similarity is

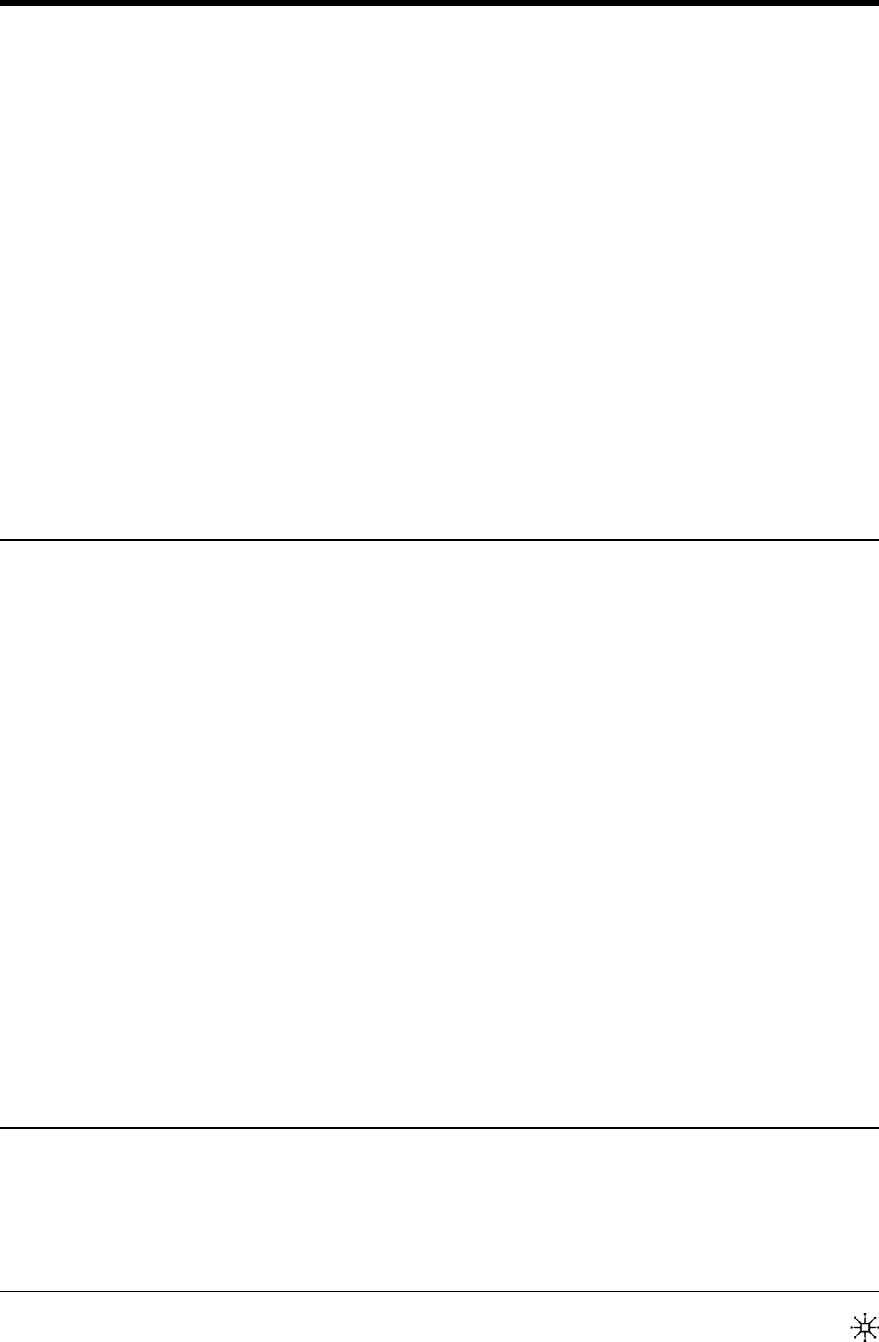

immediately apparent. Finally, Table 1 indicates the

levels of correlation among all the six classifications

considering the whole dataset.

As can be seen, the correlation between the

measures is very high. What this implies is that

although the theory suggests we change from

traditional to asymmetric measures corrected for

the negative excess returns, in practice there is

not a material change in performance rankings

of the funds from doing so.

CONCLUSIONS

This paper is a study of the performance of

Spanish domestic equity funds to determine how

one best can calculate their performance. Given

the relative youth of these funds and illiquidity of

the market, the key question is whether

traditional measures of performance (Sharpe,

Treynor and Jensen) are applicable. The study

Table 1: Correlation coefficients between two-by-two performance rankings

Sharpe Treynor Jensen S

p

(1) P(1) P(2)

Sharpe — 0.9748 0.9564 0.9198 0.9200 0.9130

Treynor — — 0.9336 0.9009 0.9113 0.9104

Jensen — — — 0.9483 0.9451 0.9449

S

p

(1) — — — — 0.9981 0.9945

P(1) — — — — — 0.9954

P(2)——————

222 Ferruz, Pedersen and Sarto

includes all funds operating the whole period

between July 1994 and December 2004.

We find significant asymmetry in biweekly

return distributions in 74 of the 85 portfolios

analysed — this represents a problem when

employing common total risk measures such as

variance or standard deviation, which require

symmetric return distributions to be valid for

general investor preferences. Moreover, we

observe that a subset of the investment funds in

the sample do not attain the average return

corresponding to risk-free assets, a situation

which also leads to anomalies in the performance

rankings resulting from measurements such as

Sharpe’s Ratio or Treynor’s Index.

In order to avoid the two aforementioned

theoretical issues, alternative performance

indices are proposed in the empirical study,

which on the one hand, include risk

measurements such as semi-standard deviation or

absolute deviation and, on the other, approach

the return premium in a relative sense.

The calculated performance rankings resulting

from the application of all the measurements

considered, however, barely differ from one

another. What this suggests is that despite the

anomalies described above, the traditional

performance metrics to be applied. While this

could be a signal that investor preferences are

generally mean–variance in nature, a more plausible

explanation is that the market has matured quite

rapidly and — much faster than some emerging

markets areas — has reached a level where tools for

analysis should be based on those tools applied in

the world’s most sophisticated markets.

DISCLAIMER

We stress that the opinions stated in this paper

exclusively reflect the view of the author and are

not those of Mercer Oliver Wyman.

References

1 Sharpe W.F. (1966) ‘Mutual Fund Performance’, Journal

of Business, Vol. 39, pp. 119–138.

2 Treynor J.L. (1965) ‘How to Rate Management of

Investment Funds’, Harvard Business Review, January-

February, Vol. 43, No. 1, pp. 63–75.

3 Jensen M.C. (1968) ‘The Performance of Mutual Funds in the

Period 1945–1964’, JournalofFinance, Vol. 23, pp. 389–416.

4 Damant D., Hwang S. and Satchell S. (2000) ‘Using a

Model of Integrated Risk to Assess U.K. Asset Allocation’,

Applied Mathematical Finance, Vol. 7, No. 2, pp. 127–152.

5 Eftekhari B., Pedersen C.S. and Satchell S.E. (2000)

‘On the Volatility of Measures of Financial Risk: An

Investigation Using Returns from European Markets’,

The European Journal of Finance, Vol. 6, pp. 18–38.

6 Konno H. and Shirakawa H. (1994) ‘Equilibrium

Relations in a Capital Asset Market: A Mean–Absolute

Deviation Approach’, Financial Engineering and the

Japanese Markets, Vol. 1, pp. 21–35.

7 Okunev J. (1990) ‘An Alternative Measure of Mutual

Fund Performance’, Journal of Business Finance and

Accounting, Vol. 17, pp. 247–264.

8 Pedersen C. and Satchell S. (2000) ‘Small Sample

Analysis of Performance Measures in the Asymmetric

Response Model’, Journal of Financial and Quantitative

Analysis, Vol. 35, No. 3, pp. 425–450.

9 Pedersen C.S. and Satchell S.E. (2002) ‘On the

Foundations of Performance Measures under Asymmetric

Returns’, Quantitative Finance, Vol. 3, pp. 217–223.

10 Sortino F.A. and Price L.N. (1994) ‘Performance

Measurement in a Downside Risk Framework’, Journal

of Investing, Fall, pp. 59–72.

11 Damant D. and Satchell S. (1996) ‘Downside Risk:

Modern Theories; Stop-and Start Again’, Professional

Investor, May-June, pp. 12–18.

12 Hwang S. and Pedersen C. (2002) ‘On Empirical Risk

Measurement with Asymmetric Return Distributions

Financial Econometrics Research Centre Working Paper

WP02-07, City University Business School, London.

13 Eftekhari B. and Satchell S. (1996) ‘Non-normality of

Returns in Emerging Markets’, Research in International

Business and Finance (Suppl 1), pp. 267–277.

14 Pedersen C. (2001) ‘Derivatives and Downside Risk’,

Derivatives Use, Trading and Regulation, Vol. 7, No. 3,

pp. 251–268.

15 Ang A.J.Chen and Xing Y. (2005) ‘Downside Risk’,

AFA Meeting, 7–9 January, Philadelphia, PA.

16 Hyung N. and De Vries C.G. (2004) ‘Portfolio

Diversification Effects of Downside RiskTinbergen

Institute Discussion Paper TI 05-008/2.

17 Campbell R. and Kraeussl R. (2005) ‘Revisiting the

Home Bias Puzzle: Downside Equity RiskWorking

Paper. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/

abstract=802704.

Performance metrics for Spanish investment funds 223

18 Cheng P. (2005) ‘Asymmetric Risk Measures and Real

Estate Returns’, Journal of Real Estate Finance and

Economics, Vol. 30, p. 1.

19 Gu L. (2005) ‘Asymmetric Risk Loadings in the Cross

Section of Stock Returns’, Working Paper.

20 Post T. and Van Vliet P. (2005) ‘Downside Risk and

Asset PricingERIM Report, Series reference No. ERS-

2004-018-F&A.

21 Morton D., Popova I. and Popova E. (2006) ‘Efficient

Fund of Hedge Funds Construction under Downside

Risk Measures’, Journal of Banking and Finance, Vol. 30,

No. 2, February, pp. 503–518.

22 Ferruz L., Sarto J.L. and Vargas M. (2003) ‘Analysis of

Performance Persistence in Spanish Short-term Fixed

Interest Investment Funds (1994–2002)’, European Review

of Economics and Finance, Vol. 2, No. 3, pp. 61–75.

23 Ferruz L. and Sarto J.L. (2004) ‘An Analysis of Spanish

Investment Funds Performance: Some Considerations

Concerning Sharpe’s Ratio’, Omega, The International

Journal of Management Science, Vol. 32, pp. 273–284.

24 Ferruz L. and Sarto J.L. (2005) ‘Some Reflections on

the Sharpe Ratio and its Empirical Application to Fund

Management in Spain’, Advances in Investment Analysis

and Portfolio Management, Vol. I, pp. 205–224, New

Jersey (USA).

25 Hwang S. and Pedersen C. (2004) ‘Asymmetric Risk

Measures When Modelling Emerging Markets Equities:

Evidence for Regional and Timing Effects’, Emerging

Markets Review, Vol. 5, No. 1, pp. 109–128.

26 Estrada J. (2000) ‘The Cost of Equity in Emerging

Markets: A Downside Risk Approach’, Emerging

Markets Quarterly, Vol. 4, No. 3, pp. 19–30.

Table A1: Asymmetry test of the investment funds of the sample

12 4.17 134 3.33 243 5.23 445 2.86

13 8.69 136 4.73 248 6.56 446 2.73

24 3.61 137 2.54 252 5.13 449 2.87

30 5.54 139 5.07 262 3.88 451 5.33

33 4.00 148 1.96 265 4.48 453 4.02

36 4.43 151 2.09 276 0.42 454 2.57

38 3.37 157 5.89 279 4.20 461 1.31

40 3.60 160 0.57 282 4.84 463 4.14

41 2.37 164 3.90 294 4.39 466 4.75

46 2.88 168 2.42 321 2.90 468 3.98

58 5.17 174 1.99 336 3.15 475 6.12

59 2.66 186 4.08 346 3.94 476 4.30

65 3.89 187 4.14 351 4.45 477 4.62

71 3.32 193 5.27 365 4.03 484 2.65

76 9.28 207 2.40 377 0.84 487 9.46

87 3.90 211 4.98 382 0.44 497 6.16

90 4.08 215 4.71 393 1.43 498 1.14

100 3.08 219 2.50 403 5.31 502 0.70

108 5.46 228 4.49 419 4.14 503 6.50

114 4.27 229 4.68 421 0.71

124 4.42 231 4.44 422 0.21

131 4.07 233 2.80 428 4.76

Note: The numbers in bold are the fund identification numbers according to the supervisor authorities of the

Spanish Market.

Appendix A

224 Ferruz, Pedersen and Sarto

Table A2: Statistics of the funds in the sample

Mean (%) s (%) b Mean (%) s (%) b Mean (%) s (%) b

12 0.19 2.30 0.60 160 0.21 3.44 0.86 377 0.67 2.22 0.42

13 0.15 2.43 0.60 164 0.28 3.65 1.00 382 0.19 1.10 0.26

24 0.14 2.11 0.53 168 0.24 3.98 1.05 393 0.04 2.29 0.54

30 0.18 1.69 0.45 174 0.27 2.48 0.63 403 0.19 1.47 0.37

33 0.24 3.15 0.85 186 0.20 3.51 0.95 419 0.23 3.63 0.91

36 0.23 3.12 0.85 187 0.23 2.06 0.54 421 0.24 2.96 0.62

38 0.12 2.44 0.63 193 0.05 2.47 0.63 422 0.17 3.00 0.69

40 0.17 2.00 0.53 207 0.20 1.34 0.32 428 0.28 3.59 0.94

41 0.15 2.71 0.71 211 0.31 1.84 0.47 445 0.11 2.52 0.62

46 0.32 2.74 0.66 215 0.20 3.06 0.83 446 0.07 2.55 0.60

58 0.27 3.48 0.95 219 0.12 2.08 0.43 449 0.14 2.43 0.62

59 0.18 3.21 0.82 228 0.26 3.61 0.97 451 0.17 1.69 0.44

65 0.13 2.99 0.76 229 0.09 3.45 0.86 453 0.27 3.81 1.05

71 0.17 1.56 0.36 231 0.03 4.00 0.91 454 0.03 2.54 0.60

76 0.02 3.46 0.85 233 0.11 2.19 0.53 461 0.15 1.95 0.47

87 0.13 1.85 0.50 243 0.14 1.94 0.46 463 0.22 3.69 1.01

90 0.30 3.59 0.97 248 0.23 1.91 0.43 466 0.17 3.29 0.89

100 0.16 1.99 0.49 252 0.23 2.30 0.59 468 0.21 1.60 0.43

108 0.31 3.44 0.94 262 0.34 3.12 0.82 475 0.30 3.48 0.92

114 0.09 2.74 0.71 265 0.23 2.79 0.72 476 0.36 3.72 1.02

124 0.19 1.46 0.39 276 0.35 1.51 0.36 477 0.35 3.73 1.01

131 0.28 3.94 1.04 279 0.07 1.87 0.48 484 0.24 1.40 0.29

134 0.35 2.73 0.73 282 0.18 3.59 0.98 487 0.11 3.66 0.91

136 0.28 3.52 0.96 294 0.09 2.38 0.32 497 0.25 3.49 0.92

137 0.06 2.74 0.67 321 0.26 2.03 0.48 498 0.19 1.05 0.27

139 0.18 2.22 0.61 336 0.22 3.00 0.78 502 0.48 1.91 0.29

148 0.09 3.01 0.72 346 0.12 3.10 0.77 503 0.10 3.28 0.82

151 0.21 2.86 0.77 351 0.23 3.46 0.94

157 0.18 2.79 0.74 365 0.13 1.78 0.45

Performance metrics for Spanish investment funds 225

Table A3: Rankings of Sharpe’s, Treynor’s and Jensen’s performance measures

Sharpe Treynor Jensen

377 0.2383 377 0.0127 377 0.0044

502 0.1771 502 0.0118 502 0.0028

276 0.1414 276 0.0060 276 0.0014

211 0.0953 211 0.0037 211 0.0007

134 0.0781 484 0.0034 134 0.0006

484 0.0695 134 0.0029 46 0.0004

46 0.0664 46 0.0028 484 0.0004

262 0.0636 321 0.0025 262 0.0002

476 0.0594 262 0.0024 321 0.0002

321 0.0591 248 0.0022 248 0.0000

477 0.0574 382 0.0022 476 0.0000

174 0.0546 476 0.0022 382 0.0000

382 0.0507 174 0.0021 174 0.0000

248 0.0502 477 0.0021 477 0.0000

108 0.0489 498 0.0019 498 0.0001

475 0.0477 207 0.0018 207 0.0001

498 0.0472 475 0.0018 187 0.0002

187 0.0466 108 0.0018 468 0.0002

90 0.0458 187 0.0018 403 0.0003

207 0.0433 90 0.0017 124 0.0003

468 0.0423 252 0.0016 475 0.0003

226 Ferruz, Pedersen and Sarto

Table A4: Rankings of the performance measures S

p

(1), P(1) and P(2)

S

p

(1) P(1) P(2)

377 216.8555 377 308.2332 377 290.8604

502 180.0280 502 267.9166 502 281.3508

276 168.0345 276 240.2057 276 213.5395

498 128.9604 382 180.9977 382 177.8486

382 127.1919 498 178.7577 498 171.9377

211 123.0518 484 164.9954 484 171.6569

484 121.5316 211 160.6403 211 163.7080

207 105.6582 207 143.5833 207 137.3943

124 95.1907 321 126.7023 248 134.1599

403 94.0620 124 126.1746 403 127.6107

468 93.1409 134 124.6339 124 125.1870

134 92.9542 403 124.0520 321 123.3775

321 91.8181 468 123.1986 468 122.6765

248 88.6346 248 116.5368 134 122.1280

46 84.3344 46 115.3256 46 111.5366

187 82.0473 174 108.6909 187 106.7029

174 79.7809 187 108.2803 71 104.2226

262 77.9133 262 104.1017 174 102.4450

71 77.0738 71 102.4261 262 102.0625

30 74.6152 30 98.3378 252 99.7181

252 72.9181 252 95.5272 30 99.2002

Performance metrics for Spanish investment funds 227