Effect of Grain Boundaries and Grain Orientation on Structure

and Properties

N. HANSEN, X. HUANG, and G. WINTHER

The evolution of deformation microstructures in metals follows a universal pattern of grain

subdivision. However, the structure in the grain boundary region may be different from that in

the grain interior, although a characteristic region cannot be identified for polycrystals with

medium to high stacking fault energy. In the grain interior, the dislocation structure is pre-

dominantly composed of almost planar boundaries (geometrically necessary boundaries) and

cell boundaries (incidental dislocation boundaries) forming a cell block structure. For grains

with grain sizes reaching down to about 4 lm deformed in tension and by rolling, a clear

correlation has been established between the characteristics of the deformation structure and the

orientation of the grain in which it evolves. A sim ilar correlation is observed for single crystals

of different orientations. Such correlations form the basis for a general analysis of active

slip systems and for modeling of the flow stress an d flow stress anisotropy of polycrystalline

samples.

DOI: 10.1007/s11661-010-0292-5

The Minerals, Metals & Mater ials Society and ASM International 2010

I. INTRODUCTION

THE microstructure evolution during plastic defor-

mation of polycrystals may differ from that of single

crystals due to grain interaction. A first attempt to relat e

the behavior of single crystals and polycrystals was

made by Sachs,

[1]

who suggested that individual grains

in polycrystals deform like free single crystals. However,

as strain continuity must be maintained across the grain

boundaries, it was suggested by Taylor

[2]

that all the

grains in a polycrystal undergo the same homogeneous

strain as the bulk mate rial. Such a homogeneous strain

will, in general, require slip on at least five slip systems.

[3]

The presence of grain boundaries was not taken into

account in the Taylor model. Boundaries may, however,

be effective barriers to slip so that local stresses

potentially build up in the grain boundary region. These

may be relaxed by secondary slip. As a result, the

microstructure evolving in the grain boundary region

may differ from that of the grain interior. The structural

evolution in these regions will be presented in the

following as an overview based on structural subdivi sion

by deformation-induced dislocation boundaries. In the

next section, correlations will be presented on the grain

scale between the characteristics of the deformation

microstructure and the crystallographic orientation of

the grain in which it forms. This leads to a comparison

of polycrystal and single-crystal beh avior followed by a

general analysis of active slip systems. In a final section,

the mechanical behavior of single crystals and polycrys-

tals will be discussed.

II. DEFORMATION

MICROSTRUCTURE—GENERAL

The characterization and analysis of deformation

microstructures will in the present paper be limited to

fcc metals with medium to high stacking fault energy

ranging from 45 mJ/m

2

(Cu) to 166 mJ/m

2

(Al).

[4]

Only

cold deformation will be discussed and at strain rates

where diffusional processes are considered to be negli-

gible. As to deformation, monotonic deformation pro-

cesses like tension and rolling will be included. By these

processes, the equivalent strain (e

vM

) has been varied

from low to medium levels (about 0.05 to 0.5, where

single glide is precluded). As a general guideline for the

structure analysis, it is assumed that the dislocations are

stored in low-energy configurations almos t free of long-

range stresses.

[5–7]

A. Grain Boundary Region

The effect of grain bounda ries during plastic defor-

mation was introduced by Kockendo

¨

rfer

[8]

who sug-

gested that the interior of a grain in a polycrystal may

deform like an isolated single crystal and the misfit

where the grains meet might be accommodated elasti-

cally or plastically. Strain accommodation in the grain

boundary region was also considered by Hauser and

Chalmers,

[9]

who suggested that it will lead to multislip

in the vicinity of the grain boundary wi thin a distance of

the order of the spacing between the slip bands, i.e.,a

few micrometers. They also suggested that the existence

of such a multislip layer (zone of misfit) of a certain

thickness might explain the grain size effect on the

N. HANSEN, X. HUANG, and G. WINTHER, Senior Scientists,

are with the Danish-Chinese Center for Nanometals, Materials

Research Division, Risø National Laboratory for Sustainable Energy,

Technical University of Denmark, DK-4000 Roskilde, Denmark.

Manuscript submitted December 23, 2009.

Article published online July 13, 2010

METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS A VOLUME 42A, MARCH 2011—613

strength of polycrystals.

[9]

The formation and effect of

such a ‘‘rim’’ being harder than the grain interior has

also been considered in various mo dels, e.g., Reference

10. An alternative approach suggested by Ashby

[11]

was

to consider the strain accommodation in terms of

dislocations, and separating the deformation of individ-

ual grains into a homogeneous deformation of the grain

interior and a local nonuniform deformation in the

grain boundary region. During homogeneous deforma-

tion, statistically stored dislocations with a density q

s

accumulate as in an equivalent single crystal, where q

s

is

proportional to the plastic strain and increases as the

slip length decreases. To correct for voids or overlaps in

the grain boundary region, geometrically necessary

dislocations of density q

g

were introduced where q

g

is

proportional to the plastic strain and inversely propor-

tional to the grain size. The total dislocation density

increases with the strain, however faster for q

s

than for

q

g

, as the slip distance decreas es rapidly with increasing

strain.

Grain interaction effects may manifest themselves by

local changes in microstructure and crystallography in

the grain boundary region. Such changes have been

observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) of

surface relief structures and by transmission electron

microscopy (TEM) of microstructures at or near grain

boundaries.

[12]

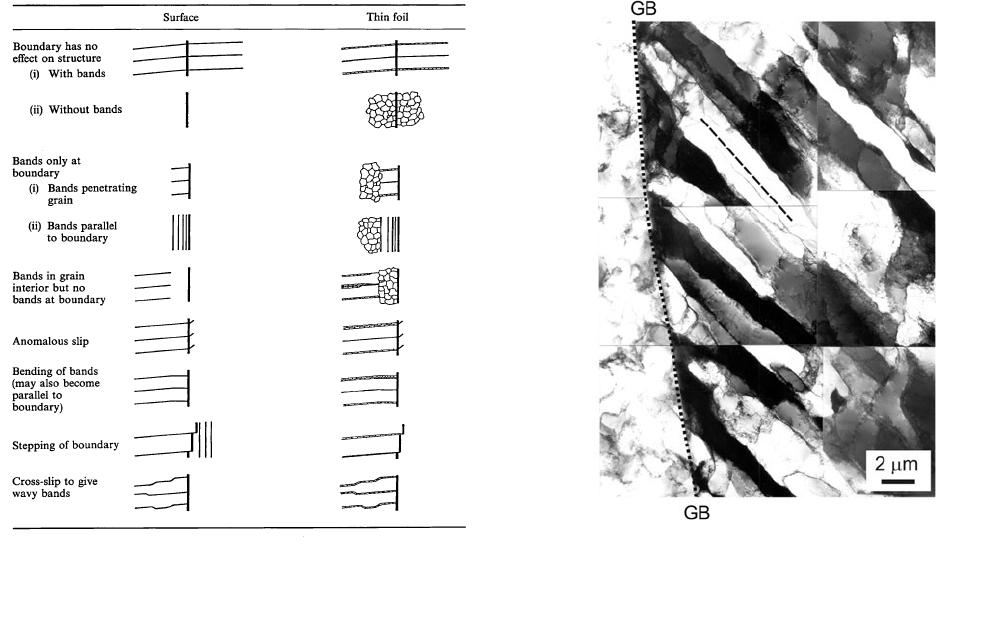

Results in Figure 1 show good agreement

between the SEM and TEM observations, which indi-

cates that the structure in the grain boundary region

may differ from that in the grain interior but also that a

grain boundary region (rim) with typical characteristics

has not formed. However, the preceding observations

also show that the interior structure may extend all the

way to the boundary. Similar observations in tensile-

deformed Al and Cu are shown in Figures 2 and 3,

respectively. Grain interaction has also been studied by

EBSD parallel and perpendicular to grain boundaries

where interaction is identified as perturbations that

reflect local changes in crystallography.

[13]

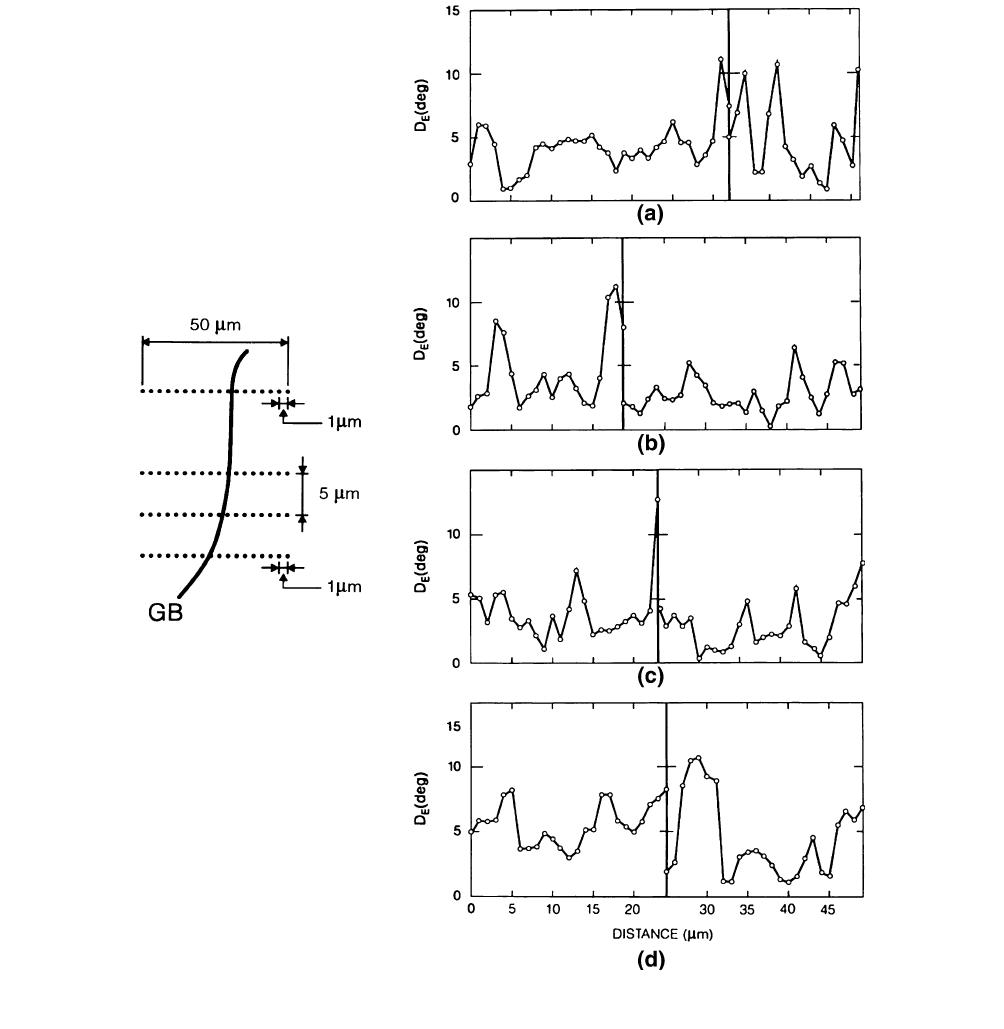

For speci-

mens deformed to 5 pct reduction in thickness by cold

rolling, significant perturbations are observed at triple

junctions but not in the grain boundary region. How-

ever, when the reduction is increased to 30 pct, pertur-

bations are observed at many grain boundaries

(Figure 4). These perturbations may extend some

micrometers into the grain from the boundary to be

compared with a grain size of about 300 lm. In order to

quantify such regions and their dependence on grain size

and strain, more extensive studies are needed, which are

now within reach with advanced EBSD techniques.

The studies of grain inter action have been coupled

with an analysis of the structural evolution in grains in

high-purity copper deformed in tension to a strain of

25 pct.

[14]

A relatively coarse grain size has been chosen,

which allows grain break-up and lattice rotations to be

followed by EBSD analysis of individual grains as a

function of strain. As shown in Figure 5, a few small

domains of special orientations provide evidence of

grain interaction. However, the crystal rotation for the

large domains covering most of the grains is consistent

with the rotation direction predicted by the Taylor

model in some, but not all, cases.

[14]

Fig. 1—Classification of structures at grain boundaries in cold

deformed aluminum. Surface structures seen by SEM or optical

microscopy in the left column correspond to structures seen in TEM

in the right column.

[12]

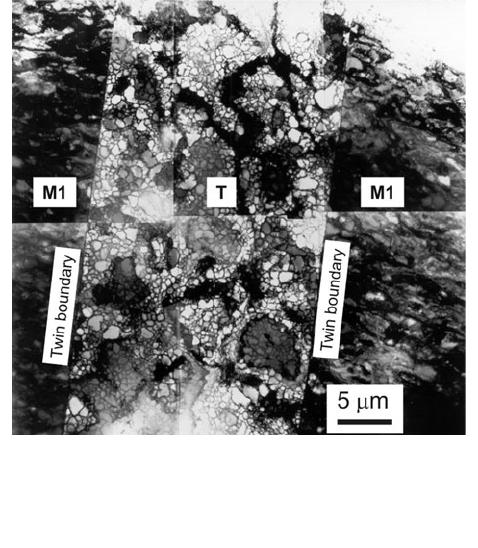

Fig. 2—TEM image showing that a uniform dislocation structure

extends from the grain interior all the way to the grain boundary in

a tensile-deformed Al.

[28]

The grain boundary is marked by a dotted

line. The dashed line on the micrograph indicates the trace of the

primary slip plane.

614—VOLUME 42A, MARCH 2011 METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS A

B. Grain Interior

The microstructural evolution in the grain interior can

be characterized as structural subdivision with easy

mobility of disl ocations that assemble into dislocation

boundaries. On the coarse scale, the structure subdivides

by the formation of domains (e.g., Figure 5) and

deformation bands; on a fine scale, almost planar

boundaries and cell boundaries forming cell blocks are

typical features. However, on an intermediate scale,

longer range orientation gradients may develop in the

cell block structure, for example, as shown by orienta-

tion imaging microscopy in pure aluminum deformed by

cold rolling.

[15]

In the following, the structural subdivi-

sion will be described based on the cell block as the basic

structural feature. Such a cell block contains a group of

cells in which the same set of slip systems operate, which

may fall short of that required for homogeneous

(Taylor) deformation, leading to the suggestion that

groups of neighboring cell blocks can fulfill the Taylor

criterion collectively.

[16]

The observed co-existence of disl ocation cells and

extended dislocation boundaries has led to a classifica-

tion of dislocation boundaries into the following:

[17]

(1) incidental dislocation boundaries (IDBs), which

are assumed to form by statistical trapping of glide

dislocations;

(2) geometrically necessary boundaries (GNBs), which

are assumed to form due to the different character

of the slip-induced glide dislocations in neighbor-

ing volumes.

Both types are typically rotation dislocation bound-

aries, which can be characterized by an axis/angle pair

and a boundary normal. This classification into IDBs

and GNBs adds to the classical distinction between

dislocations as statistically stored (redundant) and

geometrically necessary (nonredundant) dislocations

[11]

(Section A). The statistically stored dislocations are

assumed to be present in the form of tangles, dipoles,

and multipoles, which will not give rise to a significant

lattice rotation; i.e., their net Burgers vector is practi-

cally zero. In contrast, the geometrically necessary

dislocations are assumed to assemble in configurations

characterized by a lattice rotation and a net Burgers

vector. The storage of these dislocations can be random

or the dislocations can be assembled in boundaries in

which the lattice rotation is reflected in the misorienta-

tion angle across the boundary. A distinction between

statistically stored and geometrically necessary disloca-

tions is not possible through a microscopic examination

of the microstructure. However, a separation has been

attempted by X-r ay microdiffraction of deformed sam-

ples where streaking of Laue spots is interpreted as due

to an elastic strain gradient or to a distribution of

geometrically necessary dislocations. In contrast, a split

of the Laue pattern indicates angular misorientati ons

between neighboring volumes, i.e., the presence of

GNBs.

[18]

The classification of dislocation boundaries has been

the basis for the analysis of experimental observations

and their physical interpretation. In general, this anal-

ysis has covered a variety of bounda ry parameters, most

notably the spacing between and the misorientation

angle across dislocation boundaries. Sample scale aver-

age values have been obtained as well as distributions of

structural parameters. By analyzing such distributions,

it has been found that both spacing and misorientation

angle can be described by a single universal function

when each distribution is scaled by its mean angle or

spacing.

[19]

Such a scaling hypothesis ap plies to both

GNBs and IDBs, when they are analyzed separately but

not when they are grouped together. Scaling of the

spacing between GNBs has also shown a similarity in

the behavior of polycrystals and single crystals deformed

in rolling and compression.

[20]

A part of the microstructural analysis has also been to

apply the principle of similitude

[5]

expressing a fixed

relationship between structure parameters, e.g., between

the boundary spacing ( D) and the spacing (h) between

the dislocations in a boundary. Taking h inversely

proportional to the misorientation angle (h), similitude

can be expressed by the equation Dh/b = C, where b is

the magnitude of the Burgers vector and C is a constant.

For cell structures in aluminum deformed in tension and

by rolling, C varies, on average, in the range 50 to 80 rad

with no significant effect of stra in.

[6]

However, the

principle of similitude does not apply to the whole

structure as cell blocks and cells evolve differently with

increasing strain

[6]

(see Section III–D).

III. GRAIN ORIENTATION DEPENDENCE

A systematic study has been carried out on the

relationship between the grain orientation and the

dislocation structure for Al, Cu, and Ni of different

Fig. 3—TEM image taken from the cross section of a tensile-

deformed Cu. A uniform cell structure is formed in the twin (T),

which is in contrast to the structure in the matrix parts (M1). There

is no clear effect of twin boundaries on the structural evolution in

the twin and matrix parts.

METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS A VOLUME 42A, MARCH 2011—615

purities and grain sizes,

[21–29]

mainly based on TEM

characterization where great care has been taken in the

experimental design and structural characterization.

(1) The materials have been deformed in tension and by

cold rolling to study the effect of deformation mode.

(2) TEM observations have been performed in differ-

ent sample sections to obtain a precise description

of the three-dimensional (3-D) arrangement of the

dislocation structure.

(3) The crystallographic planes of GNBs have been

determined for selected grains, showing that the

GNB planes depend on the grain orientation.

The precise characterization of the 3-D morphology

and GNB planes establishes a universal pattern of

structural evolution, which is characterized by forma-

tion of three structure types leading to the conclusion

that among the materials parameters (grain orient ation,

grain size, grain boundary, and impurity) the grain

orientation is the most important in controlling the

structural evolution. This effect is described in this

section by taking a tensile-stra ined Cu polycrystal and a

cold-rolled Cu polycrystal as examples. Analysis of the

underlying processes (slip systems) governing the

development of different structure types and detailed

Fig. 4—Examples of orientation scans perpendicular to a grain boundary, sampled according to the schedule shown in the figure in 30 pct

deformed, coarse-grained sample.

[13]

616—VOLUME 42A, MARCH 2011 METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS A

comparison with single crystals are presented in Sections

IV and V.

A. Grain Orientation and Structure Types in Tension

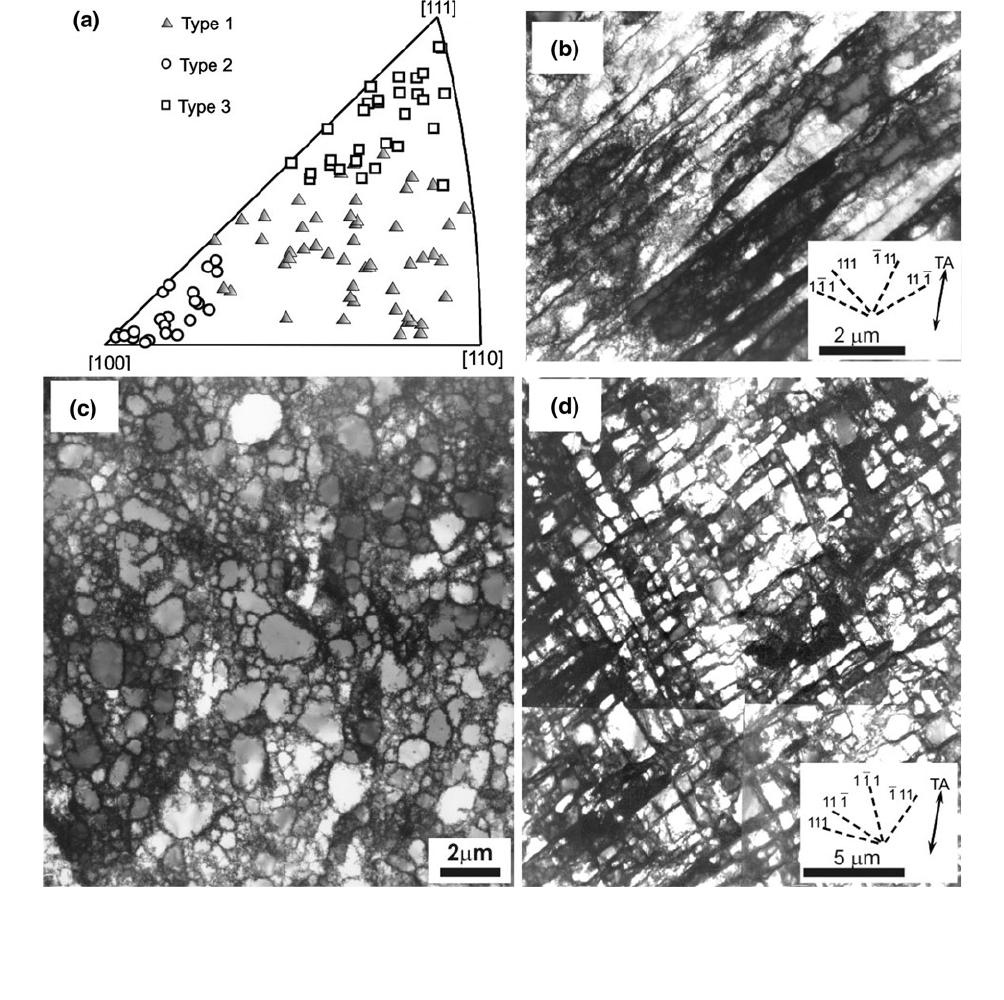

Figure 6 shows the tensile orientations of 120 grains

(Figure 6(a)) analyzed in a tensile-deformed 99.99 pct

pure Cu with a grain size of 90 lm and the three

structure types (Figures 6(b) through (d)). The charac-

teristics and dependence on grain orientation for each

structural type are summarized in the following.

[26,28]

The type 1 structure (Figure 6(b)) is a cell block

structure with cell block boundaries (GNBs) aligned

approximately with the slip planes (within 10 deg). The

grains forming the type 1 structure have their tensile

axes in the middle pa rt of the triangle (Figure 6(a)). The

GNBs are straight and parallel, and thus have a well-

defined macroscopic orientation with respect to the

tensile axis (TA). The slip plane to which the GNBs are

related is in most cases the primary slip plane defined by

the largest Schmid factor value and, in some cases, the

conjugate slip plane for grains near the [100]-[111]

boundary (where the Schmid factor of the conjugate slip

system is similar to that of the primary one).

The type 2 structure (Figure 6(c)) is a cell structure

without GNBs. The grains showing this type of struc-

ture have their tensile axes in a small area near the [100]

corner (Figure 6(a)). The cell boundaries are randomly

oriented in the cross section, as seen in Figure 6(c), and

are extended along the TA in the longitudinal section

(for examples of micrographs for tensile-deformed Cu of

different grain sizes, see References 22 and 26). There-

fore, the type 2 structure in Cu is a 3-D cylindrical cell

structure.

The type 3 structure (Figure 6(d)) is also a cell block

structure similar to type 1, but the GNBs deviate

substantially from the slip planes (>10 deg). The grains

developing the type 3 struc ture have tensile axes in the

upper part of the triangle toward the [111] corner. Each

GNB is made up of a number of long or short segments.

The majority of the segments are oriented in similar

directions with respect to the TA, but segments that

have different macroscopic orientation and form angles

of up to about 20 deg with the dominating segments also

exist. These features give rise to a fairly clear macro-

scopic inclination of the GNB s over a long distance but

a somewhat curved appearance on a local scale.

Minor morphological differences were found in the

type 2 structure between Cu, Ni, and Al. Recent

observations of tensile-deformed Ni

[29]

showed a sim ilar

3-D cylindrical cell structure as in Cu. However, the type

2 structure in tensile-deformed high-purity Al is char-

acterized by a 3-D equiaxed cell structure,

[28]

which

implies a possible effect of stacking fault energy on the

cell structure morphology. Interestingly a co-existence

of a 3-D cylindrical cell structure and a 3-D equiaxed

cell structure was observed in commercial purity Al,

indicating an effect of impurities.

[28]

B. Grain Orientation and Structure Types in Cold Rolling

Similar to the observation in tensile-deformed Al, Cu,

and Ni, three structure types and their grain orientation

dependence have also been identified in cold-rolled

samples. Figure 7 shows the results for a cold-rolled

99.99 pct pure Cu with a grain size of 90 lm. Clusters of

orientations showing a type 1 structure are seen within

15 to 20 deg of the ideal Goss, Brass, and rotated Cube

orientations. Grains within 15 deg of the Cube orienta-

tion develop a type 2 structure, which shows elongated

cell boundaries parallel to the rolling direction (RD)

in the longitudinal section. Clusters of orientations

Fig. 5—Subdivision of a coarse grain in copper deformed in tension at e

vM

= 0.08. The gray shaded regions are coarse domains, and the hashed

regions are grain interaction domains.

[14]

The white domain represents an annealing twin.

METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS A VOLUME 42A, MARCH 2011—617

showing a type 3 structure are seen >15 deg from the

Cube and along the b fiber from S to Copper. For the

type 2 structure formed in the Cube grains, when

observing the transverse section, a circular or equiaxed

cell structure was always found. The combined obser-

vations from the longitudinal and transverse sections

reveal a cylind rical morphology of the type 2 structure

in the Cube grains, basically identical to that found in

grains near the [100] corner in the tensile-strained Cu.

Recent observations

[29]

showed that the type 2 struc-

ture in cold-rolled Ni also exhibits a cylindrical mor-

phology, as in Cu described previously. However, the

Cube grains in cold-rolled Al developed a 3-D eq uiaxed

cell structure,

[29]

as found in tensile-deformed high-

purity Al.

[28]

C. Spacing and Misorientation Angles

The grain orientation does not only affect the struc-

tural morphology and the crystallographic GNB align-

ment but also the structural parameters.

[30]

This is

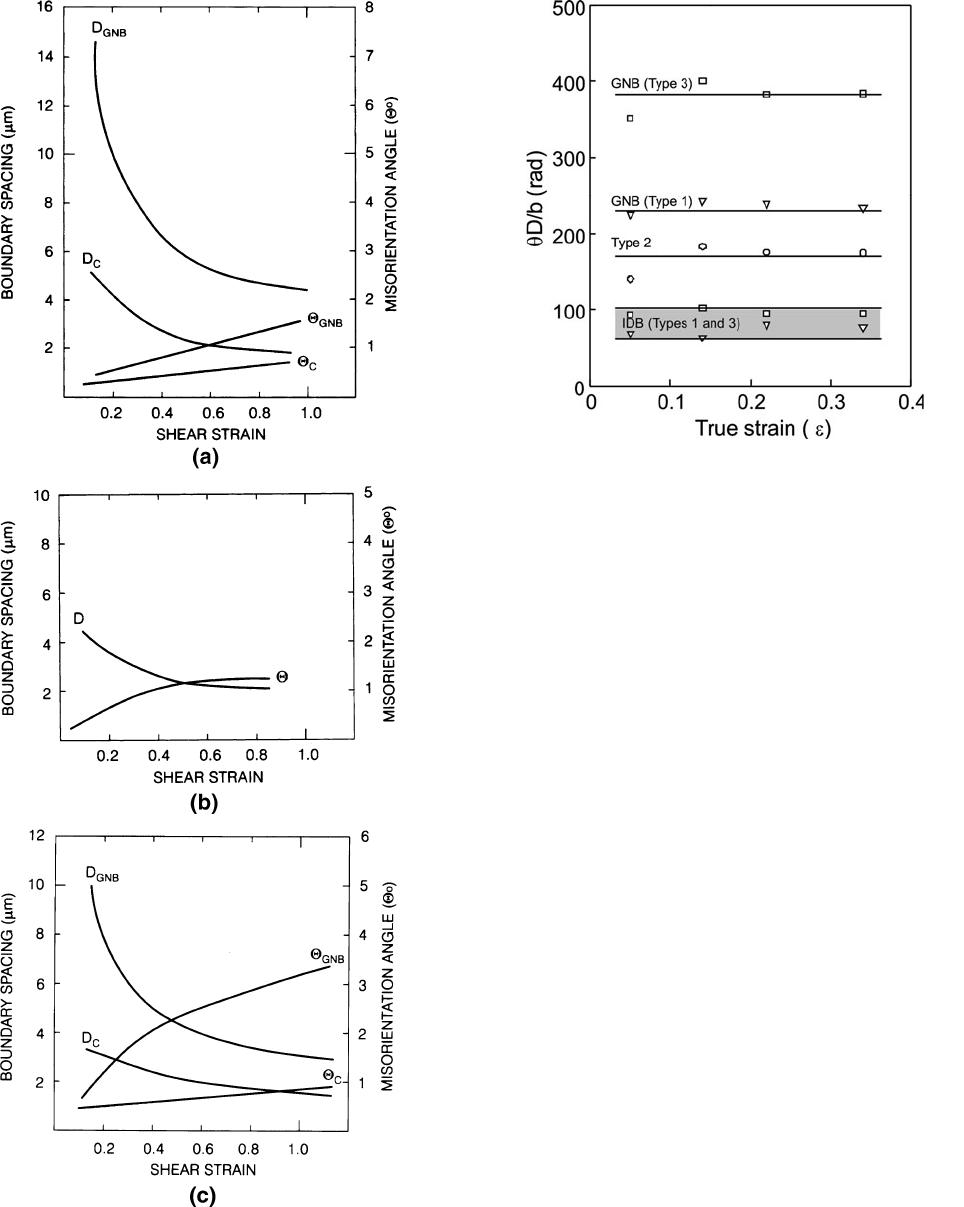

illustrated in Figure 8 showing the evolution of bound-

ary spacings and misorientation angles in grains repre-

senting type 1, 2, and 3 structures. Note that the

evolution of the type 2 parameters differs from those of

type 1 and 3, and that the evolution of spacing and angle

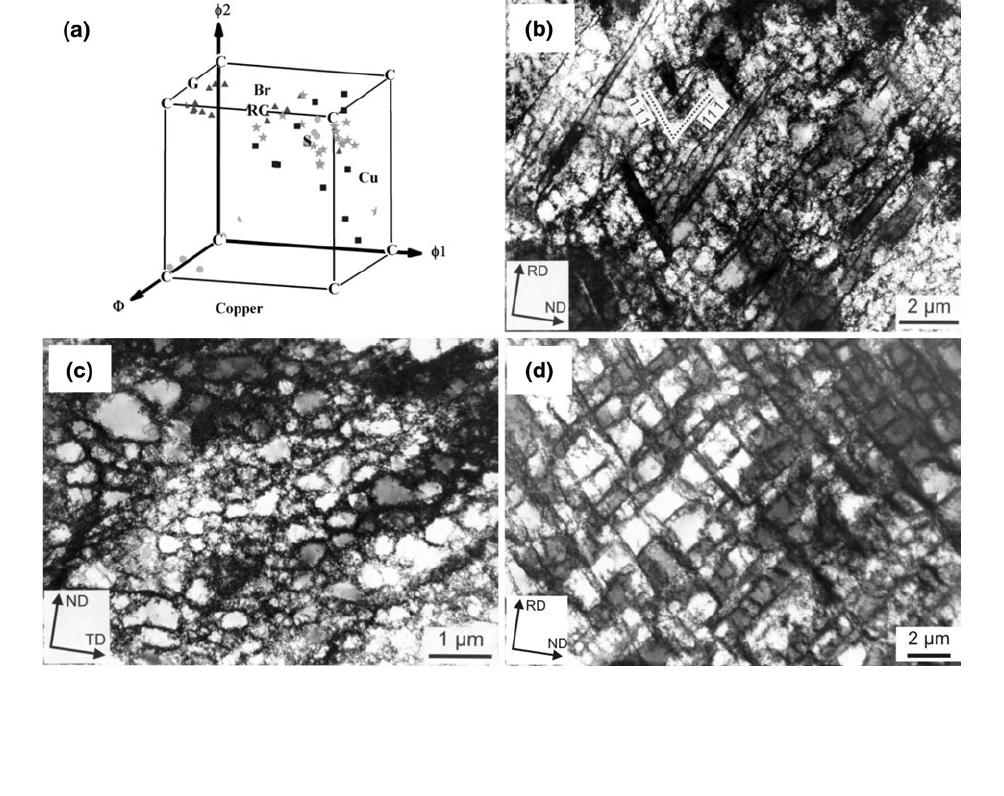

Fig. 6—Grain-orientation-dependent structure types in a tensile-strained 99.99 pct Cu (grain size = 90 lm). (a) TA orientations of 120 grains,

which have been examined.

[28]

Three symbols, filled triangle, open circle, and open square, are used to separate the grains developing type 1,

type 2, and type 3 structures, respectively. (b) through (d) TEM images to illustrate the characteristic features of (b) type 1, (c) type 2, and (d)

type 3 structures. Among these images, the ones shown in (b) and (d) were taken from the section // TA, and that shown in (c) was taken from

the section ^ TA.

618—VOLUME 42A, MARCH 2011 METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS A

for both GNBs and IDBs is more rapid in type 3

structures than in type 1 structures.

D. Scaling and Similitude

The misorientation data were analyzed according to

the scaling hypothesis,

[19]

and it was found that GNBs

and IDBs, when treated separately, agree well with

earlier observations. However, the angular variation in

the type 2 structures is not in accord, pointing to

different mechanisms of formation and evolution.

The similitude relating the boundary misorientation

angle and spacing (as discus sed in Section II–B) was also

analyzed for tensile-deformed high-purity Al. It was

found that the principle of similitude does not apply at

the sample scale average, as the cell block boundaries

and the cell boundaries evolved differently with increas-

ing strain. These findings have been confirmed by

analysing the three structure types separately. The C

values derived from the data are given in Figure 9,

which shows that C is fairly independent of the strain,

but significantly different for the different structure

types. Note, however, that all the IDBs are in the range

from 60 to 100 rad in good agreement with the earlier

measurements.

[6]

E. Effect of Grain Size

The reduction in spacing between deformation-

induced boundaries from fairly high values at low strain

(and stress) to about 1 to 4 lm at an equivalent strain of

about 1 (Figure 8) raises the question of a lower limit in

grain size for the universal evolution of type 1 through 3

deformation microstructures. For example, will such

structures form when the grain size is very small? To

address this problem, a technique is required for

producing fine-grained polycrystalline samples. This is

possible by recrystallization after deformation to very

high strain, for example, by torsion,

[27,31,32]

and it has

been possible to obtain a grain size in Cu of about 4 lm

after applying a true strain of about 8 followed by

annealing at 523 K (250 C). This sample has been

deformed in tension to true strains of 0.15 and 0.20 and

characterized by TEM.

[27]

By examining the structure in

21 grains, it has been concluded that type 1 through 3

structures evolve and that their orientation dependence

Fig. 7—Grain-orientation-dependent structure types in a cold-rolled 99.99 pct Cu (grain size = 90 lm). (a) 3-D Euler space showing the orienta-

tion of 56 grains examined.

[28]

Filled triangle, circle, and square show type 1, type 2, and type 3 structures, respectively. The star symbol shows

grains with two sets of GNBs, one of type 1 and the other of type 3. Several ideal orientations are also indicated. G: Goss (110)[001], Br: Brass

011ðÞ2

11

; RC: 45 deg ND rotated Cube (001)[110], S: (213)

3

64

; Cu: Copper (112)

1

11

; and C: Cube (001) (100). (b) through (d) TEM ima-

ges to illustrate the characteristic features of (b) type 1, (c) type 2, and (d) type 3 structures. Among these images, the ones shown in (b) and (d)

were taken from the TD section and that shown in (c) was taken from the RD section.

METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS A VOLUME 42A, MARCH 2011—619

is identical to that observed in Cu samples having larger

grain sizes (50 to 190 lm). It has also been found

[27]

that

the deformation microstructure is fairly uniform across

the area of the small grains and that a specific grain

boundary region with a structure different from that of

the grain interior has not developed.

IV. SLIP SYSTEM DEPENDENCE

The orientation dependence of the main dislocation

structure types can be explained in terms of an under-

lying dependence on the active slip systems, which

suggests that combinations of slip systems leading to

structure types 1, 2, and 3 can be identified. This further

implies that if similar slip system combinations are

activated under different circumstances, e.g., different

combinations of crystal/grain orientation and deforma-

tion mode, the structure type should be the same.

Analysis of the active slip syst ems in crystals/grains with

the different types of structures has been conducted for

tension and rolling,

[33]

focusing on cases where the active

slip systems can be predicted fairly unambiguously by

the Taylor model and Schmid factors. The result is the

identification of five classes of slip system combinations,

which lead to specific structure types. Table I summa-

rizes the relations between slip classes and structure

types, and these are described in more detail in Section A.

A. Slip Classes and Structure Types

For the type 1 structure, it is found that the GNBs

always align with a highly active slip plane.

[34]

When

conducting an even more detailed study of the type 1

Fig. 9—The principle of similitude for the GNBs and IDBs in a ten-

sile-deformed 99.99 pct Al.

[30]

Fig. 8—Dislocation boundary spacing (D) and misorientation angle

(h) as a function of strain for the three different structure types

developed in a tensile-deformed 99.99 pct Al.

[30]

The subscript C

refers to IDBs.

620—VOLUME 42A, MARCH 2011 METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS A

structure, it is found that it falls into two subcategories,

both having GNBs aligned with {111} planes but with

different systematic small deviations from the ideal slip

plane. These deviations are by rotations of a few degrees

(up to 10 deg) around a specific crystallographic axis,

which may be either a 112

hi

or a 110

hi

axis.

[27]

The

existence of these two subcategories implies an under-

lying difference in slip systems, which is the basis for

definition of two different slip classes. Detailed analysis

of a number of cases concludes that the difference lies in

the number of active slip systems on the slip plane so

that deviations around 112

hi

axes result from one active

system while the 110

hi

axes originate from activation of

two systems in the same slip plane (in the following,

referred to as coplanar systems).

[33]

For the type 2 structure, the common feature of the

slip systems is the activation of codirectional pairs of slip

systems, i.e., two systems on two different slip planes but

with the same slip direction. When comparing different

cases, it is concluded that at least two sets of codirec-

tional slip systems (i.e., a total of four systems) must be

activated to produce type 2. The sign of the dislocations

gliding on the slip systems also plays a role (Reference

33 provides more details).

For the type 3 structure, the number of subcategories

is the highest and the difference between subcategories is

much larger than for type 1. Table I lists the different

GNB planes observed and divides them into two

subcategories, each of which is associated with activa-

tion of a slip class. Please note that in all cases the GNB

planes lie far from a slip plane, in agreement with the

definition of the type 3 structure. The two slip classes

consist of the following combinations of slip systems.

(1) One set of codirectional slip systems. The GNBs

align with a plane containing the common slip

direction and bisecting the angle between the two

slip planes. The GNB lies closer to the more active

slip plane and the signs of the slip systems control

whether the GNB bisects the acute or obtuse angle

between the slip planes.

(2) So-called dependent coplanar and codirectional

slip, which is a combination of three systems on

two slip planes where one system is codirectional

and coplanar to the other two, respectively. Sev-

eral such slip system combinations may be acti-

vated in the same grain, possibly sharing some of

the slip systems, which gives rise to a number of

characteristic GNB planes. For more details, see

Reference 33.

The relations between slip classes and structure types

are of universal nature in the sense that they are not

restricted to any deformation mode or grain orientation.

The identification of these relations establishes a new

framework for the analysis and interpretation of struc-

tures, as exemplified in Sections IV–B, V,andVI–B.

B. Applica tion of Slip Classes

By means of the slip class concept, some of the

fluctuations observed between grains of similar orienta-

tion or within a grain can be better understood. The

occurrence of both type 1 and 3 boundaries a long the b

fiber of the rolling texture

[28]

is, for example, due to

activation of both a coplanar set of slip systems and a

codirectional set, leading to type 1 and 3 boundaries,

respectively. It is often observed that either the type 1 or

3 boundary is more clearly developed. In most cases,

however, the second set can also be detected. These

variations are attributed to local variations in the

relative activities of the slip systems, possibly caused

by minor strain variations or ambiguities. Analogously,

one or two sets of type 1 GNBs are found in grains of

Goss or Brass

[28]

orientation, depending on the activities

on the two slip planes with which the GNBs align. It is,

however, emphasized that these variations have their

origin in fluctuations in the relative activities of a fixed

set of slip systems, which can be pred icted based on the

grain orientation, rather than activation of new syst ems,

which can only be predicted based on detailed interac-

tions with neighboring grains.

Of course, the relations can also be used to predict the

structure based on the slip systems. For example, the

relations have been applie d to predict the dominant

alignment of the structure after torsion for the major

stable texture components, giving good agreement with

experimental observations.

[33]

This further served as a

demonstration of the uni versality by being a prediction

for a deformation mode other than tension and rolling.

The ability to predict the structure type is also vital for the

modeling of mechanical properties, as demonstrated in

Section VI.

V. SINGLE VS POLYCRYSTALS

The classification into three main types of structures,

of which types 1 and 3 can be subdivided further

according to the exact plane of the GNBs, has been

presented and analyzed above for grains in polycrystals.

Table I. Relations between Slip Classes and Dislocation Structures (Reference 33 Provides More Details)

Slip Class Crystallographic GNB Plane Structure Type

Single slip {111} type 1

Coplanar slip {111} type 1

Two sets of codirectional slip no GNBs, only cells type 2

One set of codirectional slip

symmetric

{101} or {010}* type 3

Dependent coplanar and directional slip {315}, {441}, or {115} type 3

*Depending on the signs of the Schmid factors. Asymmetric codirectional slip brings the GNB plane closer to the more active slip plane.

METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS A VOLUME 42A, MARCH 2011—621

The classification applies equally well to single crystals,

and furthermore, the structure type follows the crystal/

grain orientation in almost the same way.

A. Type 1

A comparison with the orientation dependence of

type 1 structures between single crystals and grains in

polycrystals reveals a strong similarity.

(1) In tension single crystals in the middle of the stereo-

graphic triangle exhibit type 1 structures (e.g.,

References 35 and 36). Type 1 boundaries are also

found in crystals on the 100

hi

- 111

hi

symmetry line

of the triangle when these lie more than 15 to 20 deg

away from either 111

hi

or 100

hi

:

[37]

Similarly, single

crystals on the 110

hi

- 111

hi

symmetry line exhibit

type 1 structures if they are more than about 15 deg

away from 111

hi

:

[37]

This orientation range corre-

sponds well with the occurrence of type 1 structures

in polycrystals in all orientations somewhat away

from 100

hi

and 111

hi

(Figure 1(a)).

(2) In rolling, both single crystals and grains with sta-

ble rolling texture orientations develop type 1

structures: on the a-fiber, two sets of GNBs

aligned with {111} are typically observed (single

crystals

[38–41]

and polycrystals

[23,28]

), while only one

set aligned with {111} is found on the b fiber (sin-

gle crystals

[42]

and polycrystals

[28]

), sometimes

coexisting with type 3 boundaries.

Looking at the subcategories of type 1 boundaries,

i.e., the character of the small deviations from the exact

{111} plane, the similarities also hold. In tension, type 1

boundaries deviate from the {111} plane by being

rotated slightly away from this around 112

hi

axes.

[25,28]

The exception is single crystals lying on the 110

hi

- 111

hi

symmetry line, where the corresponding axis is of the

110

hi

type.

[37]

In rolling, these small deviations from the

{111} planes are less well characterized for both single

crystals and grains, but rotation around 110

hi

axes has

been reported.

[28]

B. Type 2

In polycrystals, grains fairly close to the exact 100

hi

and Cube orientations, in tension

[28]

and rolling,

[28,29]

respectively, exhibit type 2 structures (Figures 1(c) and

7(c)). This is in good agreement with the findings in

single crystals of 100

hi

[42]

and Cube orientations ,

[44]

respectively.

C. Type 3

In tension, type 3 structures are found in both single

crystals

[43]

and grains

[28]

of near 111

hi

orientation. The

orientation range with type 3 structures in polycrystals

includes all orientations within 15 to 20 deg of 111

hi

:

Type 3 structures in single crystals have also be en

reported for crystals lying on the symmetry lines

bounding the stereographic triangle within 15 to

20 deg of 111

hi

:

[37]

To the authors’ knowledge, no data

are available on the structure type for crystals lying close

to 111

hi

but inside the triangle. Considering the subcat-

egories of type 3 structures, some differences are

reported between single crystals and polycrystals. In

single crystals, GNBs roughly aligned with {135} and

{441} planes are observed on the 100

hi

- 111

hi

and 110

hi

-

111

hi

lines, respect ively.

[37]

By contrast, the planes

reported in polycrystals are {135} and {115}.

[28]

In rolling, type 3 structures are found in grains some

distance away from the Cube orientation (right outside

the orientation range with type 2 structures).

[28,29]

This is

in agreement with the structures observed in parts of a

Cube-oriented single crystal that had rotated somewhat

away from the initial Cube orientation.

[44]

In both single

crystals and grains of near Cube orientation, the type 3

boundaries aligned with {101} planes.

[28]

Both single-

crystal

[42]

and polycrystal orientations

[28,45]

on the b

fiber of the rolling texture develop type 3 structures

(together with GNBs aligned with slip planes). For the

Copper orientation, GNBs align with {100} in both

single crystals and polycrystals.

[28,42]

D. Similarity between Single and Polycrystals

Based on the preceding analysis, it is concluded that

structures of type 1 through 3 are found in both single

crystals and polycrystals and that single crystals and

grains of similar orientations in general develop the same

structure type. This is evidence of activation of similar slip

systems. It is particularly interesting that type 1 structures

with a 112

hi

deviation axis are found in both single

crystals and grains in the middle of the triangle. It is

generally accepted that these single crystals deform in

single glide, while the Taylor model often applie d to

polycrystals predicts up to eight active systems. The

structure observations suggest that also the grains have

one dominant slip system, which may, however, be

accompanied by minor activity on other systems. It

should be noted that the lattice rotations of individual

grains of these orientations have also been observed to be

in good agreement with one dominant system.

[46,47]

However, some minor discrepancies are observed

when considering the exact GNB plane in tension

around the 111

hi

orientation. Furthermore, the expec-

tation is that single crystals fairly close to 111

hi

and

100

hi

inside the triangle will also deform in single glide,

while grains in polycrystals of these orientations develop

type 3 and 2 structures, respectively. The origin of this

discrepancy is likely to be activation of a larger number

of slip systems in grains compared to single crystals due

to the restrictions imposed by the neighboring grains

combined with the availability of a number of slip

systems with almost equal Schmid factors in these

orientation ranges. Similar discrepancies between single

crystals and polycrystals ha ve not been reported for

rolling, probably because of the inherent tendency of

rolling to induce multislip in all crystals/grains.

VI. MECHANICAL PROPERTIES

The mechanical properties of deformed polycrystals

will be affected on the sample scale by a different

622—VOLUME 42A, MARCH 2011 METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS A