Calcium Oxalate Monohydrate Precipitation at Phospholipid Monolayer Phase Boundaries

Isa O. Benítez and Daniel R. Talham*

Department of Chemistry, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida 32611-7200

ABSTRACT

The precipitation of calcium oxalate monohydrate (COM) was observed at biphasic

phospholipid Langmuir monolayers with the aid of Brewster angle microscopy. COM appears

preferentially at phase boundaries of a monolayer of 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-

phosphocholine (DPPC) in a state of liquid expanded/liquid condensed coexistance. However,

when the phase boundary is created by two different phospholipids that are phase segregated,

such as DPPC and 1,2-dimiristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DMPC), crystal formation

occurs away from the interface. It is suggested that COM growth at phase boundaries is

preferred only when there is molecular exchange between the phases.

INTRODUCTION

Calcium oxalate and calcium phosphate are the principal crystalline materials found in

urinary stones [1, 2]. The inorganic crystals are always mixed with an organic matrix composed

of carbohydrates, lipids and proteinaceous materials that account for about 2% of the total mass,

although a much larger percentage of the total volume [3, 4]. To better understand the process of

stone formation, it is important to study interactions between the organic and crystalline

components. We have previously performed a series of studies on calcium oxalate precipitation

at an interface provided by phospholipid Langmuir monolayers that serve as models for the

phospholipid domains within membranes [5-8]. We observed that the Langmuir monolayers can

effectively catalyze the precipitation of calcium oxalate monohydrate (COM) and that the

identity of the monolayer has a strong influence on the rate of crystal formation. Negatively

charged monolayers (DPPG and DPPS) induce more extensive precipitation than a neutral

monolayer (DPPC), implicating a mechanism whereby the calcium ions are concentrated at the

interface promoting nucleation [5, 6]. Consistent with this mechanism is the observation that a

large majority of crystals produced had their calcium-rich (10-1) face oriented towards the

monolayer.

Experiments performed with DPPC and DPPG at different degrees of monolayer compression

revealed that the COM number density more than doubles when the surface pressure is decreased

from 20 mN/m to 0.1-0.3 mN/m [6, 7]. These earlier studies also raised questions about the role

of monolayer phase boundaries in the crystallization process. DPPC and DPPG can exist as LC,

LE, or in a coexistence region. These effects are difficult to quantify if crystallization is

monitored ex-situ with electron microscopy. We previously demonstrated that Brewster angle

microscopy (BAM) can be used for in-situ observation of COM crystals growing at Langmuir

monolayers [5, 7]. BAM has also been recently used to monitor calcium carbonate

precipitation under fatty acid monolayers [9]. Advances in the commercial instrumentation now

allow high quality images of the monolayer and crystals located at the air-water interface. In this

study we use BAM to show the spatial distribution of the crystal growth in monolayers where

two phases are present. Two kinds of mixed-phase monolayers are studied, a single

W4.14.1Mat. Res. Soc. Symp. Proc. Vol. 823 © 2004 Materials Research Society

phospholipid in equilibrium at a phase change and a phase separated binary mixture of different

phospholipids.

EXPERIMENTAL DETAILS

Materials

All reagents were purchased from commercially available sources and used without further

purification. 1,2-Dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DPPC), and 1,2-dimiristoyl-sn-

glycero-3-phosphocholine (DMPC) (purity >99%) were purchased Avanti Polar Lipids

(Alabaster, AL).

Langmuir Monolayers

Langmuir monolayers were prepared as described previously [10]. BAM experiments were

performed using a Nanofilm Technologie GmbH (Goettingen, Germany) BAM2plus system with

the Langmuir-Blodgett trough described above. A polarized NdYAG laser (532 nm, 50 mW)

was used with a CCD camera (572 x 768 pixels). The instrument is equipped with a scanner that

allows an objective of nominal magnification of 10X or 20X to be moved along the optical axis,

producing a focused image. For the 10X objective a laser power of 50% and maximum gain is

used. A shutter timing (ST) of 1/50 s, 1/120 s or 1/1000 s is used to obtain maximum contrast

between the monolayer and the COM crystals. For the 20X objective a laser power of 80%,

maximum gain and ST of 1/50 s is always used. The distortion of the images due to the angle of

incidence is corrected by image processing software provided by the manufacturer. The incident

beam is set at the Brewster angle in order to obtain minimum signal before spreading the

monolayer. A piece of black glass is placed at the bottom of the trough to absorb the refracted

light beam that would otherwise cause stray light. The polarizer and analyzer are set at 0° for all

experiments. The laser and camera are mounted on an x-y stage that allows examination of the

monolayer at different regions.

RESULTS

We have previously observed that COM forms at the phase boundary between gas

analogous (G) and LE phases of a DPPG monolayer [7]. COM crystals also appear

preferentially at phase boundaries when LC and LE phases coexist, as has been observed

by Vogel and coworkers using light scattering microscopy in combination with

fluorescence microscopy [11]. We found that precipitation at LC/LE phase boundaries

also occurs under our experimental conditions. A DPPC monolayer was compressed to 5

mN/m on a calcium oxalate subphase of RS 5 and temperature of 21.8 ± 0.1 °C [12].

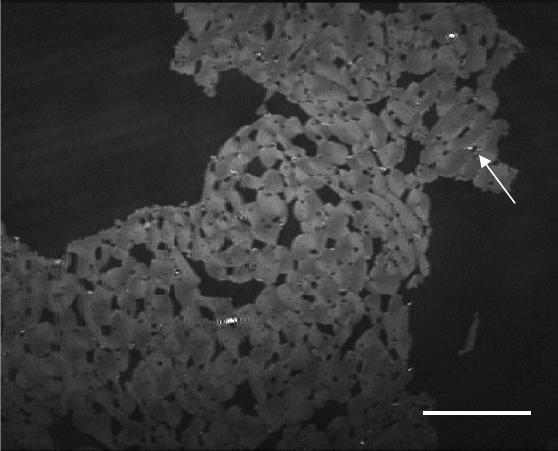

BAM imaging clearly shows extensive crystal formation at phase boundaries after 16

hours, Figure 1.

W4.14.2

Figure 1. DPPC compressed to 5 mN/m over an RS 5 calcium oxalate subphase after 16 hours

(ST = 1/120 s). The dark background is the LE phase and the light grey is the LC phase. COM

appears as bright spots at the LE/LC phase boundary. The arrow shows an example of a crystal.

The scale bar represents 100 µm.

A phase boundary can also be created by mixing phospholipids that phase segregate. We

chose a 1:1 mixture of DMPC and DPPC at 21.8 ± 0.1 °C on an RS 5 subphase since, under

these conditions, only DPPC can form an LC phase while DMPC remains in the LE phase upon

compression. At high mean molecular areas an LE phase is observed. Upon further

compression, a critical pressure (15 mN/m) is reached where DPPC begins to form LC domains.

The mixture remains phase separated at all pressures higher than 15 mN/m [13]. We chose a

pressure of 25 mN/m to carry out the COM precipitation as the LC domains did not increase in

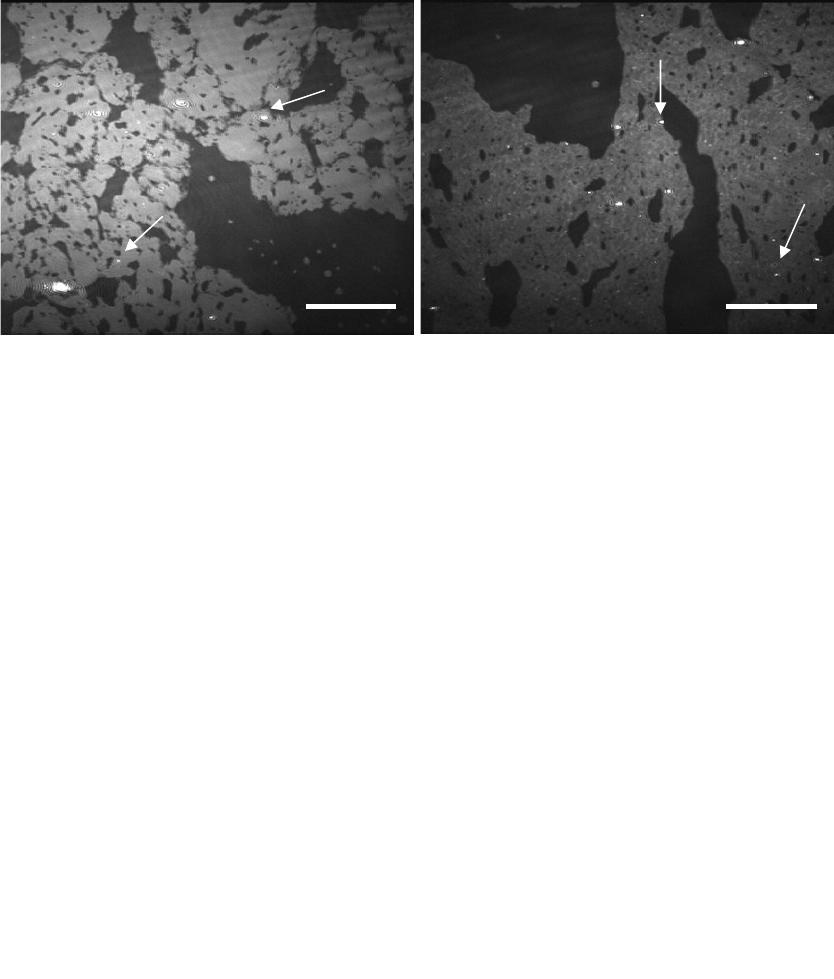

size upon further compression, indicating complete lipid segregation. Crystals were observed to

grow exclusively on the DPPC domains as shown in Figure 2a. Even after 24 hours the

precipitation remains exclusive to DPPC. Although control experiments (not shown) confirm

that DMPC is able to catalyze crystal formation as a pure LE monolayer, the crystal precipitation

is preferred at the DPPC monolayer, demonstrating that phase segregated films can be used to

explore directly the effect of different phospholipids on crystal precipitation. It is noteworthy

that in the present case, although there is an interface between LC and LE phases, COM does not

grow at the phase boundaries. This effect becomes quite apparent when Figures 1 and 2a are

compared. Although both monolayers are held at the same temperature and subphase

composition and both have LE/LC phase boundaries, the COM crystals form exclusively at the

phase boundary in the DPPC monolayer and away from it in the binary mixture.

W4.14.3

Figure 2. BAM images of a 1:1 DPPC:DMPC monolayer over an RS 5 calcium oxalate

subphase held at (a) 25 mN/m after 24 hours (ST = 1/50 s) where the dark grey background is

DMPC and the light grey islands are LC DPPC and (b) 18 mN/m after 11 hours (ST = 1/120 s)

where the dark grey background is LE DPPC and DMPC, the light grey islands are LC DPPC.

The bright spots are COM. The arrows show COM growth at (a) the LC domains and (b) phase

boundaries and LC domains. The scale bars represent 110 µm.

A binary mixture held at a lower pressure, 18 mN/m, will produce a monolayer with pure

DPPC LC domains and a mixture of DPPC and DMPC in the LE matrix. Under these conditions

COM precipitation remains exclusive to the DPPC domains, but in this case, the crystal

formation now occurs both at the phase boundary and away from it. This situation is illustrated

by Figure 2b. Unlike the situation in Figure 2a, where DPPC and DMPC are completely

segregated, at 18 mN/m DPPC is in equilibrium between LC and the mixed DPPC/DMPC LE

phase. This dynamic exchange between phases appears to be a condition for crystals to appear at

the phase boundary.

DISCUSSION

BAM provides a useful tool to visualize and quantify the effect of changes such as pressure,

subphase composition, and phospholipid identity on the COM number density [5-7]. BAM has

the advantage of being a relatively inexpensive in-situ technique, which does not require COM

crystallization to be halted for observation. Studies of COM precipitation at DPPC monolayers

with two phases in equilibrium revealed that crystal formation occurs preferentially at the phase

boundary, either LC/LE or LE/G. Similar results were seen previously for DPPG [7]. The

preferential precipitation at LC/LE boundaries has also been observed by BAM for CaCO

3

under

fatty acids [9] and by light scattering microscopy combined with fluorescence microscopy for

calcium oxalate [11].

We have shown here that the role of phase boundaries in COM precipitation can be further

explored by preparing monolayers of phase-segregated phospholipid mixtures. Phase-separated

binary phospholipid mixtures have been more commonly examined in-situ by fluorescence

microscopy [14-18] and in transferred films by AFM [15, 19-21], but it is also possible to

observe the segregation by BAM. The COM precipitation at a 1:1 DMPC:DPPC mixture at

25mN/m occurred exclusively at the DPPC domains. This result is consistent with earlier studies

a b

W4.14.4

on individual phospholipids that showed that for the same functional headgroup, more crystals

will form at the phospholipid that is able to achieve a LC state [7]. Nucleation is preferred at

DPPC because even though DMPC is more fluid, it cannot organize as densely as DPPC under

the current conditions. In contrast to the single component mixed-phase systems, the

precipitation occurred away from the interface at all times up to 24 hours (Figure 2a). At surface

pressure of 25 mN/m, the binary mixture is not in equilibrium and the lack of molecular

exchange between the LC and LE phases seems to prevent the COM formation at the boundaries.

This observation is supported by the fact that if a similar film is prepared at a lower pressure,

where DPPC is in both phases and the LC and LE are in equilibrium, crystal precipitation is

again observed at the phase boundaries.

The question remains whether COM nucleation indeed occurs at the phase boundaries or

rather crystals adhere there after forming elsewhere. Andelman [22] has shown through

experiments with latex beads suspended at pentadecanoic acid monolayers, that a charged

particle with a net dipole moment will be attracted to LC domains which act as macrodipoles.

Vogel has suggested this mechanism applies to COM growth at lipid monolayers [11]. While

not observed directly by BAM, it is possible that COM nucleates at the LE phase and before it

can be detected by BAM moves to the LC phase boundary. Although the high ionic strength of

our subphase might attenuate this mechanism [13], it cannot be ruled out. An alternative is that

extensive nucleation indeed occurs at the dynamic phase boundaries. The phase boundaries are

active sites and lipids located there can readily reorganize to accommodate the requirements of

binding to an inorganic crystal face.

CONCLUSIONS

Phase separated binary phospholipid mixtures were monitored in situ with BAM and it is

shown that phase boundaries can play an important role in COM formation. We have observed

crystal precipitation at phase boundaries when there is molecular exchange between the LE and

LC phases, such as for DPPC held at 5 mN/m and 22 °C where the LC and LE phases coexist.

On the other hand, at segregated mixtures of two related phospholipids, DMPC and DPPC, COM

growth was selective at the DPPC LC phase and not observed at the DMPC LE phase or at the

phase boundary. If the conditions are changed so that the DPPC can exchange between the LE

and LC phases, crystals again appear at the phase boundaries. The role of the phase boundaries

is still not certain.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the National Institutes of Health, Grant RO1 DK59765, for support of this work.

REFERENCES

1. E. L. Prien and E. L. Prien, Am. J. Med. 45, 654 (1968).

2. A. Smesko, R. P. Singh, A. C. Lanzalaco, and G. H. Nancollas, Colloids and Surfaces 30,

361 (1988).

3. S. R. Khan and R. L. Hackett, J. Urol. 150, 239 (1993).

4. W. H. Boyce and F. K. Garvey, J. Urol. 76, 213 (1956).

W4.14.5

5. S. Whipps, S. R. Khan, F. J. O'Palko, R. Backov, and D. R. Talham, J. Cryst. Growth.

192, 243 (1998).

6. R. Backov, S. R. Khan, C. Mingotaud, K. Byer, C. M. Lee, and D. R. Talham, J. Am. Soc.

Neph. 10, S359 (1999).

7. R. Backov, C. M. Lee, S. R. Khan, C. Mingotaud, G. E. Fanucci, and D. R. Talham,

Langmuir 16, 6013 (2000).

8. S. R. Khan, P. A. Glenton, R. Backov, and D. R. Talham, Kidney International 62, 2062

(2002).

9. E. Loste, E. Diaz-Marti, A. Zarbakhsh, and F. C. Meldrum, Langmuir 19, 2830 (2003).

10. I. O. Benitez, R. Backov, S. R. Khan, and D. R. Talham, Mat. Res. Soc. Symp. Proc. 774,

209 (2003).

11. W. R. Schief, S. R. Dennis, W. Frey, and V. Vogel, Colloids and Surfaces A:

Physicochem. Eng. Aspects 171, 75 (2000).

12. Although a pressure of 5 mN/m yields a pure LE phase at 25 °C, the lower temperature

causes a phase transition to occur at a lower pressure, yielding a LE/LC coexistance.

13. I. O. Benitez and D. R. Talham, Langmuir, submitted (2004).

14. S. Koppenol, H. Yu, and G. Zografi, J. Colloid Interface Sci. 189, 158 (1997).

15. P. Moraille and A. Badia, Langmuir 18, 4414 (2002).

16. B. M. Discher, W. R. Schief, V. Vogel, and S. B. Hall, Biophys. J. 77, 2051 (1999).

17. C. K. Park, F. J. Schmitt, L. Evert, D. K. Schwartz, J. N. Israelachvili, and C. M. Knobler,

Langmuir 15, 202 (1999).

18. A. Gopal and K. Y. C. Lee, J. Phys. Chem. 105, 10348 (2001).

19. Y. F. Dufrene, W. R. Barger, J.-B. D. Green, and G. U. Lee, Langmuir 13, 4779 (1997).

20. I. Reviakine, A. Simon, and A. Brisson, Langmuir 16, 1473 (2000).

21. J. Sanchez and A. Badia, Thin Solid Films 440, 223 (2003).

22. P. Nassoy, W. R. Birch, D. Andelman, and F. Rondelez, Phys. Rev. Lett. 76, 455 (1996).

W4.14.6