European Journal of Information Systems (1998) 7, 241–251 1998 Operational Research Society Ltd. All rights reserved 0960-085X/98 $12.00

http://www.stockton-press.co.uk/ejis

Evaluating information systems in small and medium-sized

enterprises: issues and evidence*

J Ballantine

1

, M Levy

1

and P Powell

2

1

Information Systems Research Unit, Warwick Business School, University of Warwick, Coventry CV4 7AL;

2

Department of

Maths and Computing Sciences, Goldsmiths College, New Cross, London SE14 6NW, UK

Much empirical work has investigated the nature of information systems (IS) evaluation in large organiza-

tions. However, little work has examined the nature of evaluation in small and medium-sized enterprises

(SMEs). This paper discusses IS evaluation in the context of SMEs by identifying a number of issues

particularly relevant to such organizations. Drawing on the experiences of four SMEs, the paper identifies

the following factors and their implications for evaluation practice: a lack of business and IS/IT strategy;

limited access to capital resources; an emphasis on automating; the influence of major customers; and

limited information skills. The paper draws on two frameworks of evaluation which are used to help

understand evaluation practices in SMEs, and which form a structure within which future research may

be placed. The paper concludes with a set of propositions which constitute a research agenda for further

examining evaluation practice in SMEs.

Introduction

The problematic nature of information systems/

information technology (IS/IT) evaluation is well recog-

nised. However, the majority of empirical work in IS

evaluation has been carried out in large organizations.

Indeed, many of the techniques of evaluation are predi-

cated upon complex organizations with sub-units com-

peting for organizational funding. What is less rese-

arched is whether many of the problems of IS/IT

evaluation are atypical of some organizational types (for

instance, service and manufacturing) or organizations of

varying sizes (for example, small, medium and large

companies). This paper discusses the theme of organiza-

tion size in the context of IS evaluation by identifying

the issues surrounding evaluation in small and medium-

sized enterprises (SMEs). In doing so, it considers

whether contextual factors such as management style

and organizational culture constrain or amplify the

evaluation problem.

The paper first considers the characteristics of SMEs

which distinguish them from large companies. It then

outlines approaches to evaluation, drawing on evaluation

practice. This highlights the expectations for evaluation

practices in SMEs. Evidence of the actual evaluation

practices of four SMEs in the manufacturing sector of

the UK West Midlands is used to illustrate these. In so

doing the paper identifies a set of issues which have

particular relevance for evaluation practices in such

*An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 5th European

Conference on Information Systems, Lisbon, Portugal, July 1996.

organizations. This paper draws on two frameworks of

evaluation which are used to help understand evaluation

practices in SMEs, and which form a structure within

which future research may be placed. It concludes with

a set of propositions which constitute a research agenda.

SMEs are a major business sector in the industrial

world and are of fundamental importance in less

developed countries and peripheral European regions. In

the UK, SMEs represent over 95% of all businesses

registered for VAT, employ 65% of the workforce

(Storey, 1995) and produce 25% of gross domestic pro-

duct (Natwest, 1992). The SME sector is characterised

by high firm failure rates. Storey and Cressy (1995)

report that about 11% of small businesses fail to survive

in any given year—the failure rate being six times higher

for small than large businesses. Indeed, over five years

80% of all new small businesses fail. It may be that dif-

ficulties of evaluation practice in such organizations con-

tribute to this high failure rate, if inadequately appraised

investments are frequently undertaken.

Storey and Cressy also characterise SMEs as exhibit-

ing many of the attributes of firms in perfect compe-

tition. SMEs have little ability to influence market price

by altering output; they have small market shares and

are unable to erect barriers to entry to their industry;

they cannot easily raise prices and tend to be heavily

dependent on a small number of customers. The bulk of

these businesses produce standard products, termed ‘me

too’ businesses by Storey and Cressy.

242 Evaluating information systems in SMEs J Ballantine et al

Research method

The IS/IT evaluation practices of four SMEs are dis-

cussed in this paper. Evaluation practices were ascer-

tained by conducting interviews with relevant individ-

uals, including top management and IS personnel.

Interviews were semi-structured, addressing inter alia

the following: the extent to which investments in IS/IT

were subject to evaluation; the criteria used to make

investment decisions; the extent to which an IS/IT and

business strategy existed, the influence of major cus-

tomers and the IS skills available within the organiza-

tions.

The four SMEs discussed here are manufacturers,

three supply the motor industry, and the fourth

assembles light fittings. Those supplying the motor

industry are a precision tool manufacturer, a manufac-

turer of automotive springs and a company which makes

a variety of tube or wire-based products (for example,

clutch shafts and pedal assemblies). The companies have

between 24 and 285 employees, and turnover ranges

from £1.6 million to £12 million. They are all family-

owned businesses which have either been taken over by

a larger group (in both cases overseas companies) or

which have introduced general managers to widen the

decision-making base. All the firms have introduced

information systems to aid production activities and use

IBM AS400 hardware, with a variety of materials

requirements planning (MRP) software.

The next section of the paper synthesises the literature

on IS/IT evaluation to establish expectations for the

SME evidence which follows. The section considers the

background to the evaluation problem; approaches avail-

able to deal with this problem; and the use of such

approaches in practice.

Evaluation of information

systems/technology

IS/IT evaluation is a major organizational issue, with

many studies highlighting concerns over IS effectiveness

measurement, cost justification and cost containment

(Dickson & Nechis, 1984; Niederman et al, 1991). The

issue has, to some extent, come to the forefront of man-

agement attention due to the level of capital expenditure

involved. Investment in IS/IT is currently estimated at

betwen 1–3% of turnover (Willcocks, 1992), putting it

on a par with spending on research and development.

IS/IT evaluation is problematic, principally as a result

of the difficulties inherent in measuring the benefits and

costs associated with such investments (Ballantine et al,

1995a). The IS literature has begun to acknowledge the

extent of these problems, and has recognised the need to

consider the wider organizational context within which

evaluation takes place. As a result, a number of evalu-

ation techniques which attempt to take a broader per-

spective than the traditional financially-oriented tech-

niques have emerged. Despite these developments, there

is widespread agreement that there is a lack of evaluation

tools which effectively address the problems.

Symons and Walsham (1988) argue that IS/IT evalu-

ation is difficult because of the multi-dimensionality of

cause and effect and multiple, often divergent, evaluator

perspectives. Evaluation, they argue, should not simply

be viewed as a set of tools and techniques, but a process

which must be understood fully in order to be effective.

Angell and Smithson (1991) echo this by arguing that

‘evaluation of an IS cannot be an objective deterministic

process based on a positivist “scientific” paradigm, such

a “hard” quantitative approach to social systems is mis-

conceived’.

Approaches to evaluation

In an IS context, evaluation has been defined as the pro-

cess of ‘establishing by quantitative and/or qualitative

means the worth of IT to the organization’ (Willcocks,

1992). However, multiple purposes of evaluation are

recognised. Farbey et al (1993), for example, identify

that evaluation serves a number of objectives: as a means

of justifying investments; to enable organizations to

decide between competing projects, particularly if capi-

tal rationing is an issue; as a control mechanism,

enabling authority to be exercised over expenditure,

benefits, and the development and implementation of

projects; and as a learning device enabling improved

evaluation and systems development to take place in the

future. Others (Dawes, 1987; Ginzberg & Zmud, 1988)

identify similar rationales for IS/IT evaluation: to gain

information for project planning; to determine the rela-

tive merits of alternative projects; to ensure that systems

continue to perform well; and to enable decisions con-

cerning expansion, improvement, or postponement of

projects to be taken.

There are many documented approaches to IS/IT

evaluation. Powell (1992), for instance, develops a

classification which recognises objective and subjective

evaluation methods. Objective methods attempt to attach

values to system inputs and outputs, while subjective

methods consider wider aspects of evaluation such as

user attitudes. Objective methods (cost–benefit analysis

(CBA), value analysis, multiple criteria approaches,

simulation techniques, etc), he argues, endeavour to cat-

egorise the costs associated with information systems.

On the other hand, subjective methods (user attitude sur-

veys, event logging, delphi evidence, etc) ‘try to quantify

in order to differentiate between systems, but the quanti-

fication is of feelings, attitudes and perceptions’.

While a wealth of evaluation techniques are to be

found in the IS literature, many of these have focused

historically on quantitative, as opposed to qualitative,

approaches. Hirschheim and Smithson (1988) spell out

the dangers of such approaches which, they argue, can

Evaluating information systems in SMEs J Ballantine et al 243

lead to a positivistic rather than an interpretivistic

approach being taken. To counter this, more recent work

attempts to widen the IS/IT evaluation debate. As a

result, a number of models which recognise the context

of evaluation have been put forward. Information eco-

nomics (Parker et al, 1989), for example, introduces the

concepts of value, risk and human and management fac-

tors. Farbey et al (1993) discuss the use of multi-objec-

tive, multi-criteria methods which start from the assump-

tion that the worth of an IT project can be determined

in a measure other than money. The approach adopts a

stakeholder perspective, recognising alternative views of

stakeholders. Other techniques, for example, utilisation,

benchmarking, simulation, aggregate scoring techniques

and user attitude surveys, are also discussed in the litera-

ture.

Evaluation practice

The evaluation of IS/IT investments in practice is well-

documented (Blackler & Brown, 1988). However, the

majority of studies tend to concentrate on the extent to

which financial techniques, such as payback, net present

value and internal rate of return, are used to justify

investments. Hochstrasser (1992), recognises the limited

use of evaluation techniques in practice, suggesting that

there is a lack of available tools which aid management

with the task of evaluating, prioritising, monitoring and

controlling IS/IT investments. Farbey et al (1993) also

suggest that the range of evaluation methods used in

practice is limited.

The practice of evaluation is problematic for many

organizations. Willcocks (1992), for example, identifies

a number of major problems with evaluation practices

in the UK: budgeting practices tend to conceal full costs;

there is a failure to understand and budget for human

and organizational costs; knock-on costs are frequently

overstated; costs are overstated in order to ensure that

projects are developed within time and budget; there are

various problems associated with using traditional based

evaluation techniques; organizations often neglect intan-

gible benefits in the evaluation process; and finally, risk

is not fully investigated. Some of these problems are

confirmed by empirical studies (Tam, 1992; Ballantine

et al, 1995a). However, few of the issues are addressed

in the context of small firms. These are investigated in

the next section.

SMEs and evaluation: the issues

This paper examines how four manufacturing SMEs

make decisions on the development and implementation

of IS investments. The characteristics, including princi-

pal products, ownership, number of employees and turn-

over, of the firms are shown in Table 1. Also indicated

are the IS investments which were the subject of evalu-

ation. All the information systems have been purchased

within the last five years. In three cases the purchase

occurred more recently and implementation is only par-

tially complete (companies A, C and D). In two cases

(companies C and D) the decision to purchase an IS,

and the system actually chosen, was taken by the finance

director. In the case of company A the managing director

was instrumental in the purchase, while in company B

the operations manager was the driving force. A detailed

analysis of the four firms using Pascale and Athos’s

(1981) Seven-S model can be found in Appendix A. The

analysis of each SME has been carried out from the per-

spective of the role of information systems in the organi-

zation as proposed by Galliers and Sutherland (1991).

The following sections identify a set of evaluation

issues which, when compared to the extant literature, are

seen to be specific to the type of organization concerned.

These include: the lack of both a business and IS/IT

strategy; limited access to capital resources; a focus on

using IS/IT to automate as opposed to informate; a lack

of planning effort; the nature of the relationship between

the organization and its principal customers; limited

information skills; and finally, a lack of focus on inte-

gration of IS/IT.

Business and IS/IT strategy

The IS literature recognises that evaluation of IS/IT

investments should be aligned closely with an organiza-

tion’s IS/IT strategy, and also the need to align IS/IT

strategy with business strategy. The SMEs studied do

not have a clearly defined IS/IT or business strategy.

However, while no explicit strategy exists, an implicit

one often does. For all firms the strategy is one of sur-

vival (see Appendix A) leading to a focus on efficiency

and cost reduction. Despite these implicit strategies,

problems still exist as the strategy itself is neither writ-

ten, nor indeed in one case, imparted to senior manage-

ment. Lederer and Mendelow (1986) identify this as a

problem for IS/IT developers in larger organizations

where corporate strategy may neither be formed fully nor

communicated. For example, in company C the finance

director was unaware that the parent company was con-

sidering relocating production to the developing world,

leaving the UK to focus on product design. Company

B’s decision to purchase IS was a reaction to the need

for more information about production in an increasingly

growing and complicated business, as opposed to stra-

tegic considerations. This concurs with Hagmann and

McCahon (1993) who report that fewer than 30% of the

300 SMEs they studied undertook any strategic planning.

Hagmann and McCahon also find that fewer than 50%

of the SMEs that owned or planned to purchase a spe-

cific IS devoted any significant planning effort to it. IS

planning encapsulates not just the purchase of infor-

mation systems, but concomitant issues such as manage-

ment of the systems, organizational changes and inte-

gration with current technology architectures (Galliers,

244 Evaluating information systems in SMEs J Ballantine et al

Table 1 Characteristics of SMEs

Company Product Ownership Employees Turnover Information Systems

A Car springs Originally family 112 £4.5m AS400 with MRP system; MD has

owned now part of PC-based performance measurement

US group system

B Light Family owned 130 £5m AS400 with MRP system, networked

fittings terminals. Three EDI systems, one

linked to MRP system

C Precision Originally family 24 £1.6m AS400 with MRP system. Finance

tools owned now part of Director has standalone PC with

German group spreadsheet. Marketing department

have standalone PC. Standalone

CAD/CAM system

D Clutch Family owned 285 £12m AS400 with MRP system. EDI link

assemblies with major customer also used of

CAD transfer. Not linked to MRP.

Finance director has stand-alone PC-

based performance measurement

system

1991). Indeed, Galliers (1991) recommends that the

organization’s information requirements should be the

key driver for information systems. The purchase of an

MRP system formed the main recent effort of all the

SMEs here. In company A the managing director was

looking for efficiency improvements and asked a con-

sultant for advice. However, organizational change,

training and human resource issues were not considered

and the MRP system merely provides some information

about inventory levels. There was no consideration about

systems integration, flexibility or growth.

The lack of strategic planning, both business and

IS/IT, which takes place in SMEs, has implications for

IS/IT evaluation. One major implication is the lack of a

clear yardstick or objective against which to measure the

feasibility of potential IS and guide the decision process.

The investment decisions of the four SMEs were made

using purely financial criteria. In particular, the extent

to which the potential system would affect the level of

turnover as a result of investment was widely used.

However, the use of crude financial criteria and sub-

sequent financial techniques of evaluation are likely to

preclude the incorporation of other factors critical to suc-

cess, including, quality and flexibility. However, as fin-

ancial measures such as turnover might, indeed, reflect

SMEs’ critical success factors, the problems of using

solely financial techniques may be somewhat less than

for larger organizations.

Limited access to capital resources

Access to capital by SMEs is often limited due to restric-

ted sources of financing in terms of borrowing or equity.

Blili and Raymond (1993) recognise that this sub-

sequently leads to weakness in ‘financing, planning, con-

trol and information systems and training’. Both com-

pany A and C are owned by larger groups which provide

capital without the need for borrowing. Both A and C

had to make business cases for the investment in IS and

justify the cost in terms of improving efficiency. Com-

pany B, however, was constrained by limited funds

while needing to satisfy quality demands of its, at that

time, only customer. They worked with a local software

supplier to develop an MRP system and effectively acted

as a test site for the developer that hoped to sell the

system to others. Therefore, less capital was employed

than might otherwise have been required. Company D

was able to take advantage of the availability of grants

from local and central government to relocate their fac-

tory on the basis of creating employment in a deprived

area. This capital injection enabled the company to pur-

chase its MRP system.

There are a number of implications for evaluation

practice of limited capital resources. First, there is a limit

to the number of investments which are normally evalu-

ated at any time. In all four cases, only MRP systems

were being considered. As a result there is less need to

use an evaluation technique which facilitates prioritis-

ation of projects. Thus, techniques of evaluation which

consider a single investment in isolation may suffice.

The associated weaknesses in planning and control of

information systems of SMEs additionally results in a

lack of feedback on IS/IT investments such that they are

unlikely to be able to identify whether anticipated bene-

fits have been achieved, and if not, why. The advantages

of evaluation in terms of providing feedback for control

purposes, in addition to feedforward for planning, are

Evaluating information systems in SMEs J Ballantine et al 245

unlikely to be achieved by SMEs. A further implication

is the resulting emphasis placed on the development of

incremental systems. This is confirmed by Hashmi and

Cuddy (1990) who find that developments in SMEs are

largely incremental, both for management information

systems and advanced manufacturing systems.

Emphasis on automating

In the SMEs researched here there is a greater emphasis

on using IS/IT to automate rather than informate

(Zuboff, 1988). This is particularly evident in the type

of information systems invested in. The predominant

systems are MRP, generally used in a productivity strat-

egy (Hashmi & Cuddy, 1990), their primary function

being to improve efficiency through automation of trans-

action processing systems. Hence their focus is on

achieving existing productivity levels for a lower lab-

our cost.

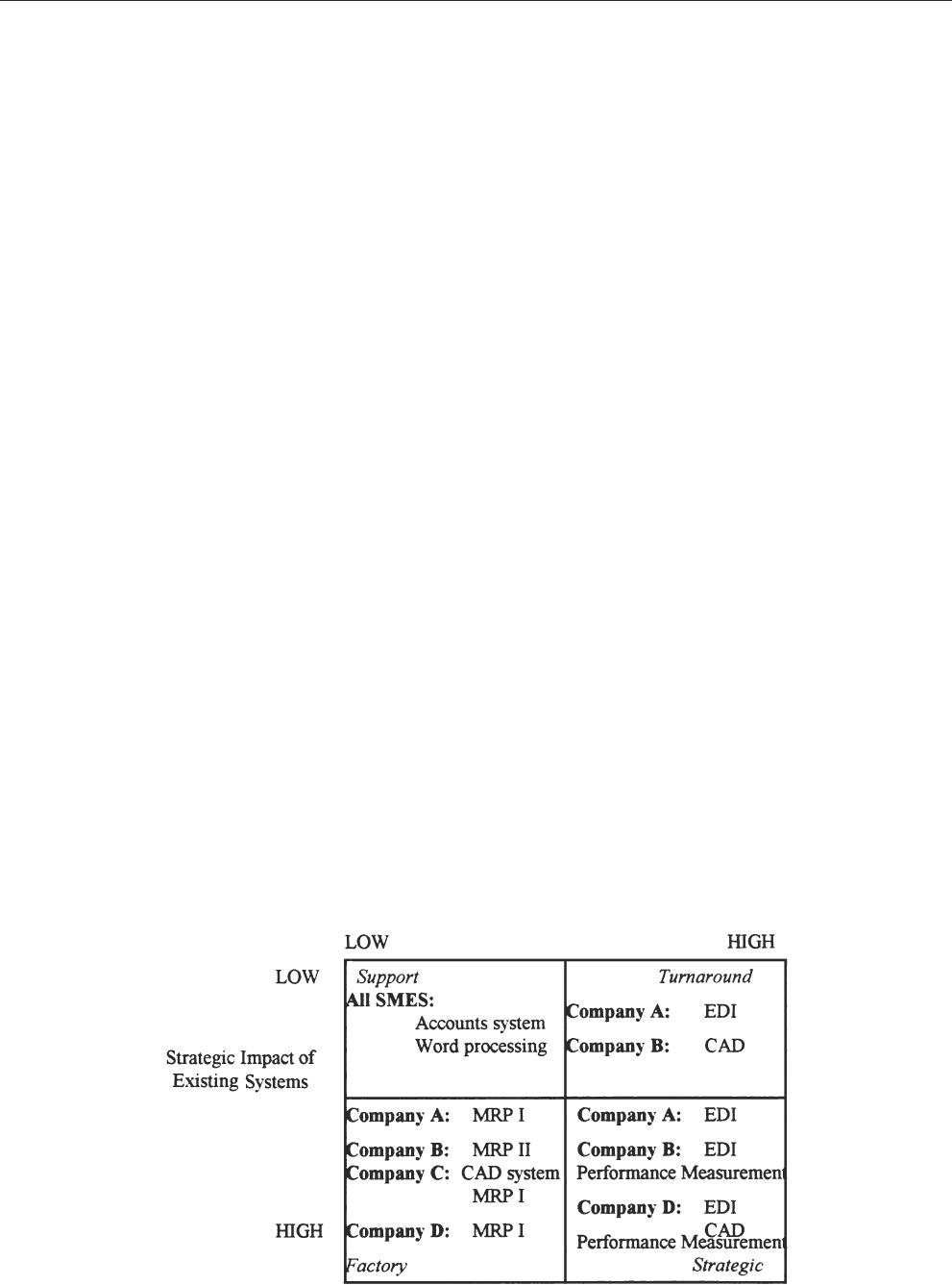

Application of the McFarlan–McKenney grid to the

SMEs indicates the role of information systems (see Fig-

ure 1) which are primarily directed at supporting oper-

ations as opposed to providing management information.

For example, company A can obtain management reports

from the production support system, but they tend to be

very detailed, necessitating the re-entry of data to a spre-

adsheet to provide summary reports. The MRP system

is only used to identify stock and raw material avail-

ability, it is not used to plan production. A similar situ-

ation occurs in company B where the detailed reports

from the production support system require considerable

manual analysis by a manager to derive any useful infor-

mation. Company C, having purchased an MRP system

has not yet fully implemented it. The MRP system is

designed to manage the accounts, customer and suppliers

details as well as stock control. They are gradually

Figure 1 The role of information systems.

implementing the system, meanwhile they are working

with a batch stock control system and paper files. Com-

pany D is in a similar position to company A, with re-

entry of data required to provide quality measurement

information about the product and process required to

satisfy customers and improve the business.

To summarise, the SMEs recognise the need for good

operational systems to ensure that they can deliver to

customers on time. The data is generally used to manage

the operational process effectively. However, there is

very little attempt to gain any added value from this

information except for pressure from customers requir-

ing quality information. Evaluation of IS is, therefore,

only based on whether they will provide information to

improve efficiency. The potential for learning and devel-

opment for the SMEs is unlikely to be evaluated.

Influence of major customers

An issue which increases the problematic nature of

evaluation in the SMEs is the influence of key cus-

tomers. This is particularly marked, for example, where

a condition of being a supplier to a major company is

that electronic data interchange (EDI) is implemented.

In this case the choice of system rests not with the SME

but with the customer. Thus, the SME is ‘forced’ to

make an investment decision over which they have little

or no control. Here, evaluation is not seen as an issue

by the companies who implemented EDI systems. For

example, company D was required by one of its major

customers to introduce EDI which enabled automatic

order processing and design processing through com-

puter aided design (CAD). The requirement to evaluate

the costs of developing an interface to their major cus-

tomer was not considered; rather, it was a necessity. In

addition, company D was unable to consider alternative

246 Evaluating information systems in SMEs J Ballantine et al

interfaces which might have given them future flexibility

to add other customers. As a result they are locked into

the software supplier who developed the interface. Com-

pany B has also gone through similar experiences. The

company had, until recently, three major customers, to

one of which they have been the prime supplier for many

years. An EDI link was developed with this firm several

years ago. However, this customer decided to diversify

its supplier base with the result that company B has been

forced to seek other customers. Despite success in ident-

ifying another major customer, a further EDI system has

had to be purchased. Company C works more informally

with its customers although it is being put under con-

siderable pressure by a major customer to purchase EDI.

They are reluctant to make the investment on cost

grounds as they are only turning round the company after

the recession and cannot readily see benefits from the

introduction of EDI.

The experiences of the SMEs here reinforces the

influence of major customers on SMEs, which has impli-

cations for IS evaluation. For example, it may be more

appropriate in these circumstances to carry out collabor-

ative evaluations with the business partner concerned.

Alternatively, if SMEs are required to adopt systems and

are given little or no say over the investment decision,

then evaluation is unlikely to be a worthwhile exercise

beyond simply assessing its affordability.

Limited information systems skills

A further difficulty SMEs face is limited information

systems skills. In selecting IS, SMEs are dependent on

external consultants and software companies. Whilst the

managers of the SMEs here are generally comfortable

with their understanding of the business, and, therefore,

their information requirements, they are largely depen-

dent on external sources for advice on appropriate hard-

ware and software. Company A, for example, recognised

that it could not continue to process its accounts manu-

ally after acquiring a number of smaller competitors. The

managing director accepted that his knowledge of IS was

limited and employed an independent consultant to

undertake a systems analysis. As a result, an accounting

package was purchased on the consultant’s recommen-

dation. Evaluation of the system was, however, based

purely on the extent to which it was capable of pro-

cessing accounting information within the limited budget

available. Further systems development is being under-

taken by the operations manager who is self-taught.

Company B is reliant on a software supplier who is a

sole trader. There is some concern as the health of the

supplier is in some doubt. Company B has a considerable

amount of operational data, but it cannot easily be

extracted in a format useful to managers. For example,

the operations manager spends three days a month ana-

lysing stock discrepancies manually, a task that could be

carried out automatically by a report program. However,

it is seen as difficult to amend the system. Company C,

again, is reliant on the software supplier to provide sup-

port and advice. The company is continually under

pressure to take the latest updates and changes by the

software company. Company C takes the view that they

will make no changes until forced by the threat of no

further support for that part of the system. Company D

has a part-time programmer who changes the system as

required by management. On the positive side in all the

SMEs, senior management have spreadsheet skills and

are able to undertake detailed financial analyses as

required. However, this requires the re-entering of data

as the spreadsheets are not integrated with operational

systems.

Limited IS skills in SMEs have implications for evalu-

ation. There is a reliance and dependence on outsiders to

provide both technical and systems advice and support.

Outsiders, especially small suppliers, are unlikely to

have a breadth of experience in system development, or

if they do it is likely to be from the structured school

of development methods which do not consider a wide

range of stakeholders and tend to produce inflexible sys-

tems based on a limited understanding of the current and

future business. Thus, the evaluation procedures they

adopt are likely to be objectively-based.

Effects on evaluation practice: SMEs and large firms

Findings from the four cases suggest that SME charac-

teristics have implications for evaluation practices.

Additionally, the focus of evaluation in SMEs differs

from that found in larger organizations. The prime driv-

ers for investment are pressure from customers and an

emphasis on improving efficiency. Evaluation decisions

are also made in isolation, in that the decision to invest

in an IS is not made in competition with other systems.

Limited strategic planning means that information sys-

tems are purchased as required, hence their evaluation

may be assessed more by financial criteria than might

be the case with larger companies. There is no evidence

of intangible costs being assessed, indeed financial con-

sideration of the cost of the system is the main criterion

by which it is judged.

Discussion

This section presents two frameworks; the first is used

to understand more fully why SMEs might adopt a parti-

cular type of evaluation practice; while the second pro-

vides a structure within which future research might

address the issues. The paper concludes by developing

a set of propositions which constitute a research agenda

for IS evaluation in SMEs.

Ballantine et al (1995b) present a framework used

here as a means of explaining and understanding the

evaluation approaches adopted in SMEs. Table 2 sets

out the framework which recognises the extent to which

Evaluating information systems in SMEs J Ballantine et al 247

Table 2 Approaches to evaluation

Method of Little consideration of Much consideration of

evaluation process of evaluation process of evaluation

Standard Routine accounting Sceptical use of

models accounting models

e.g. NPV, CBA,

Non- ‘Strategic’, naive Considered approach

standard

organizations consider the process of evaluation, and the

subsequent use of standard or non-standard evaluation

approaches for capital investments. While the framework

considers the arguments for adopting standard versus

non-standard approaches to evaluation for all capital

investments, it can also be used to understand further

why SMEs have adopted the particular evaluation prac-

tices evidenced here.

The framework identifies four alternative approaches

to evaluation, each characterised by either the use of a

standard or non-standard evaluation method, and the

degree to which the process of evaluation is considered.

For example, organizations that give little consideration

to the process of evaluation are likely to use standard

evaluation methods, such as routine accounting models,

for evaluating all capital investments.

The ‘blind’ use of a standard approach to evaluation

may be the result of a lack of knowledge of the process

or tools of evaluation, or of the project itself. The former

would be more likely to occur in SMEs or in those which

do not regularly carry out evaluation. A lack of data or

knowledge about the project itself may reflect its novelty

or the firm’s lack of desire to commit resources to plan-

ning. Other reasons for using a standard approach might

be that SMEs see themselves as followers of a particular

technology, not leaders, hence evaluation has already

been done for them by others and they can clearly see

the results of implementing the technology elsewhere.

Organizations that give much consideration to the

evaluation process yet use standard evaluation

approaches might do so because they recognise that it is

appropriate to adopt a standard approach on the grounds

of equity. Alternatively they might recognise that, while

sceptical of using standard methods, either no alternative

is available, or there are no justifiable reasons for the

adoption of non-standard evaluation practices.

Organizations that give little consideration to the

evaluation process, yet use a non-standard approach

might do so on the basis that IT/IS is almost always in

some way strategic. Alternatively, a rigid approach to

evaluation might not fit with the organization’s culture,

or the evaluators do not consistently believe in the pro-

cess, the methods, or the outcomes of using a standard

approach. Finally, IT/IS budgets may be infrequent and

ad hoc so that consistent evaluation practice is not feas-

ible.

In the final quadrant are those organizations that give

much consideration to the process yet use a non-standard

approach to evaluation. The overwhelming reason why

organizations might fall within this quadrant revolve

around the argument that at any time the range of invest-

ments considered by an organization are so varied that

a standard approach is unlikely to encapsulate all sig-

nificant features which need to be considered in the

evaluation process.

The evaluation practices examined in this research

suggest that SMEs fall in the quadrant using a standard

evaluation approach after little consideration of the pro-

cess. Indeed, the study confirms that little consideration

of the evaluation process is undertaken. This, however,

is a function of a number of factors including a lack

of business and IS/IT strategy; limited access to capital

resources; and limited skills within the organizations.

Further, the emphasis in the SMEs here is on the adop-

tion of a homogeneous technology, which is primarily

used to automate, adds further to the argument for adopt-

ing a standard evaluation approach for all IS invest-

ments. It would be informative to see whether a standard

approach is also adopted for evaluating other capital

investments, and the extent to which that approach is

similar to the one adopted for IS.

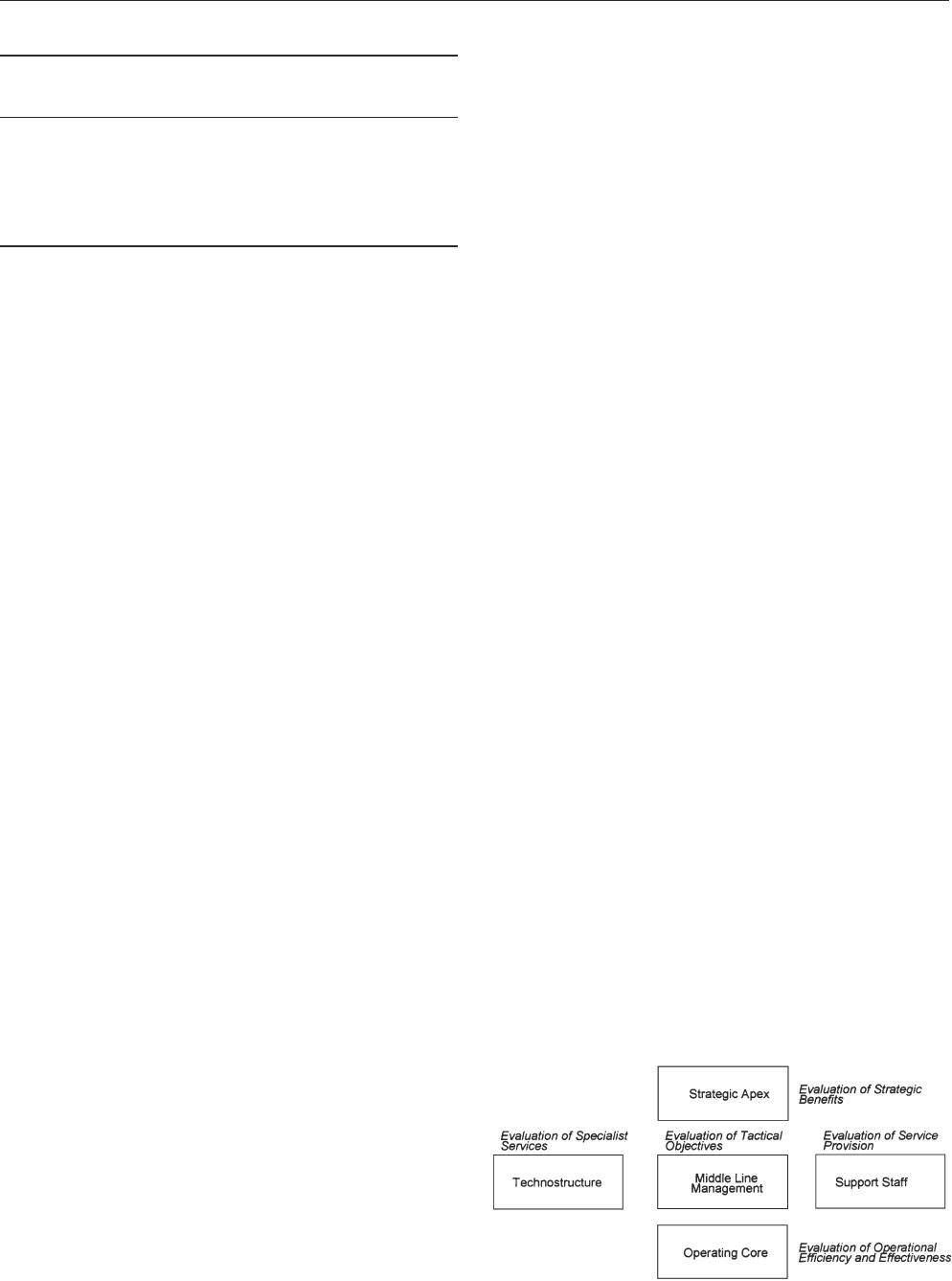

Farbey et al (1993) developed a framework of evalu-

ation which enables the benefits of IS to be analysed

from an organizational perspective. The framework,

derived from Mintzberg’s (1983) model of organiza-

tional structure, is shown in Figure 2. Farbey et al make

the point that the benefits of an IS investment may be

seen from different perspectives, by different parts of the

organization, and that there is, therefore, a need to con-

sider them holistically.

However, attempts to apply the model to SMEs in its

current form is fruitless given the five issues discussed

earlier. The model may, however, be adapted for use in

SMEs (see Figure 3).

As discussed, the SMEs here do not have a clear view

Figure 2 Source: Farbey et al (1993).

248 Evaluating information systems in SMEs J Ballantine et al

Figure 3 Source: adapted from Farbey et al (1993).

of their strategic direction, which results in a failure to

use IS/IT as a competitive tool. Therefore, while not at

odds with Farbey et al on the importance of strategic

benefits, the lack of strategic direction and emphasis on

efficiency in SMEs mean that little attention is given to

strategic evaluation. The technostructure is defined by

Farbey et al as those ‘people whose function it is to

influence the way people work’ and would include indi-

viduals such as operational researchers. However, the

experiences of the four SMEs here suggests there is little

reflection on the way work is carried out within the

organization. Rather, there are more urgent pressures in

SMEs which leave little time for reflective thought con-

cerning the effectiveness of operations. Therefore evalu-

ation of the technostructure in SMEs is unlikely to be

an issue.

Farbey et al (1993) recognise three further categories

of IS benefits which are not encapsulated by Mintzberg’s

model of organizational structure: information benefits;

communication benefits; and learning benefits

(Mintzberg, 1983). However, the evidence here suggests

that SMEs principally use information as a means of

improving productivity and not as a means of enhancing

communication and learning, which makes the three

additional categories of benefits of less relevance.

Further, the limited access to management information

in SMEs makes it unlikely that the feedforward element

of evaluation implied by the strategic and technostruc-

ture elements of the Farbey model would be considered

by SMEs. Thus, the Farbey et al model may be adapted

for examining evaluation in SMEs by excluding the stra-

tegic and technostructure elements.

The findings of the cases suggest that the evaluation

of tactical objectives, operational objectives and service

provision are more appropriate to SME evaluation given

the issues discussed earlier.

Research agenda

This paper has identified five issues influencing the IS/IT

evaluation processes in SMEs: a lack of business and

IS/IT strategy; limited access to capital resources;

emphasis on automating; influence of major customers;

and limited information skills. This section develops a

set of propositions which constitute a research agenda

for further examining evaluation practices in SMEs.

The absence of an explicit business and IS/IT strategy

within SMEs suggests that:

Proposition 1: SMEs will adopt less formal capital invest-

ment decision-making processes than larger organizations.

Since planning activities are minimal in SMEs, the

resulting lack of clear objectives against which to evalu-

ate potential investments is likely to lead to less con-

sideration of the process of evaluation and the strategic

benefits of IS (Farbey et al, 1993) than is evident in

larger organizations. Similarly, SMEs are more likely to

make investment decisions which are based on flawed

decision processes since the evaluation approach

adopted is unlikely to be documented, adding further to

the adoption of ad-hoc, inconsistent and informal

approaches to evaluation. However, the lack of strategy

further suggests that:

Proposition 2: SMEs are poorer in their ability to identify

when investments in IS/IT might be used to gain strategic

advantage than large companies.

The absence of an explicit business strategy implies

not only a lack of clearly defined business objectives, but

also the absence of a clearly defined means of achieving

objectives. Given this, SMEs are unlikely to recognise

the strategic importance of potential IS/IT investments

which might surface as a result of engaging in a strategic

planning process. Additionally, lack of strategy will not

facilitate an understanding, and realisation, of the tech-

nostructure benefits (Mintzberg, 1983) of potential IS

investments in SMEs.

Additionally:

Proposition 3a: the absence of a business and IS/IT strategy

leads to greater emphasis on individual projects, as opposed

to portfolio effects of IS/IT projects in SMEs.

This approach to evaluation encourages organizations to

consider IS/IT investments in isolation, largely ignoring

the holistic nature of such systems, which implies an

inability to reap the synergistic benefits of IS/IT invest-

ments which might otherwise accrue.

Following Proposition 3a, limited access to capital

resources within SMEs suggests that:

Proposition 3b: SMEs need not adopt evaluation processes

which facilitate prioritisation of IS/IT investments.

However, the adoption of such an approach to evalu-

ation might further encourage organizations to ignore the

synergistic effects which a portfolio of investments

Evaluating information systems in SMEs J Ballantine et al 249

might deliver, which, in turn, further emphasises the

development of incremental systems.

Given a lack of strategy:

Proposition 4: SMEs are unlikely to view the IS/IT evalu-

ation process as a learning mechanism.

The emphasis of evaluation in SMEs is more likely

to be one of control rather than learning. As a result, the

learning benefits of IS identified by Farbey et al (1993)

are unlikely to be considered in the evaluation process.

However, the extent to which control mechanisms exist

and are effective in SMEs is an area which requires

more examination.

The emphasis in SMEs on automating as opposed to

informating leads to the conclusion that:

Proposition 5a: financial techniques of evaluation are more

appropriate for evaluating investments in IS/IT in SMEs

than in large organizations as these reflect the nature of pro-

jects invested in.

Investment in automation projects is normally under-

taken in order to achieve cost efficiencies. Thus, finan-

cial evaluation techniques which primarily focus on the

identification of quantifiable costs and benefits are more

likely to be appropriate methods of evaluation for such

investments.

In addition:

Proposition 5b: financial evaluation techniques are appro-

priate for evaluating investments in IS/IT in SMEs as these

techniques reflect the factors critical to the success of

SMEs themselves.

The critical success factors reflecting SMEs survival,

and ultimately success, include, for example, short term

liquidity, profitability and cash flow. Thus, financial

techniques of evaluation which emphasise these aspects

are more appropriate for the purposes of evaluation in

SMEs. For example, the extensive usage of payback as

a means of evaluating IS/IT investments is well-docu-

mented in the literature. The use of payback recognises

the need to recoup the original investment within a per-

iod of time (on average two years for IS/IT investments

in the UK). The payback approach, thus, emphasises the

importance of liquidity and so it is likely to be an appro-

priate technique of evaluation since it reflects one of the

critical success factors of SMEs.

As discussed, many SMEs are heavily influenced by

their major customers in terms of the systems they are

required to adopt. This suggests that:

Proposition 6: customer influences in SMEs are more likely

to lead to decisions which are based on a ‘got-to-do’ basis,

rather than on a formal, rational decision process.

Where major customers exert considerable influence

over SMEs in terms of the systems they are required to

adopt, decisions regarding the adoption of a particular

technology is best taken on the basis of efficiency criteria

or no evaluation where the customer has specified a

particular system as a pre-requisite for trading. This

reiterates the earlier arguments that financial techniques

are possibly more appropriate techniques of evaluation

in SMEs than other more qualitative techniques.

The lack of information skills within SMEs suggests

that:

Proposition 7a: SMEs exhibit much greater reliance on the

IS/IT decision-making processes of external bodies (for

example, consultants, software companies, and external

accountants) than large companies.

Reliance is primarily due to a lack of internal IS skills

and few IS personnel in SMEs. This leads to the final

proposition:

Proposition 7b: SMEs are more likely to invest in industry

standards and established systems than large companies.

For example, SMEs will invest in technologies which

have been subjected to testing by others in the industry.

In addition, they are also more likely to purchase

software which has been extensively tried and tested, as

opposed to developing bespoke software or recently

developed off-the-shelf software.

The propositions discussed above constitute a research

agenda for further examining evaluation practices in

SMEs. Research is needed to investigate further how

evaluation practices differ between SMEs and larger

organizations, and the extent to which the evaluation

issues described earlier hinder SMEs from using IS/IT

strategically. In addition, as small firms are likely to

behave in diverse ways, future research should contrast

the evaluation practices of SMEs which exhibit many of

the problems outlined earlier with those which do not.

The best way to progress such research is likely to

involve a pluralistic approach.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this paper argues that organizational size

is a factor which has largely been ignored in IS evalu-

ation research to date. Further research is needed to

examine the extent to which size influences the adoption

of particular evaluation practices. Two frameworks are

also discussed as a means of structuring and exploring

future research. Finally, the paper has presented a set of

propositions which constitute a research agenda.

250 Evaluating information systems in SMEs J Ballantine et al

References

Angell IO and Smithson S (1991) Evaluation, monitoring and con-

trol. In Information Systems Management: Opportunities and Risks.

p 3, MacMillan.

Ballantine JA, Galliers RD and Stray S (1995a) The use and

importance of financial appraisal techniques in the IS/IT investment

decision-making process. Project Appraisal 10(4), 233–241.

Ballantine JA, Galliers RD and Powell P (1995b) Daring to be

different, capital appraisal and technology investments: In Proceed-

ings of the Third European Conference on Information Systems

(Doukidis G et al, Eds), 1, pp 87–98, Athens, Greece.

Blackler F and Brown C (1988) Theory and practice in evaluation:

the case of the new information technologies. In Information Systems

Assessment: Issues and Challenges (Bjorn-Anderson N and Davis

BB, Eds), pp 351–374, Oxford, North Holland, Amsterdam.

Blili S and Raymond L (1993) Information technology: threats and

opportunities for small and medium-sized enterprises. International

Journal of Information Management 13, 439– 448.

Dawes GM (1987) Information systems assessment: post implemen-

tation practice. Journal of Applied Systems Analysis 14, 53–62.

Dickson GW and Nechis M (1984) Key information systems issues

for the 1980’s. MIS Quarterly 8(3), 135–149.

Farbey B, Land F and Targett D (1993) IT Investment A study of

Methods and Practice. Butterworth Heinemann.

Galliers RD (1991) Strategic information systems planning: myths,

reality and guidelines for successful implementation. European

Journal of Information Systems 1(1), 55–64.

Galliers RD and Sutherland A (1991) Information systems man-

agement and strategy formulation: the stages of growth model

revisited. Journal of Information Systems 1(1), 89–114.

Ginzberg MJ and Zmud RW (1988) Evolving criteria for information

systems assessment. In Information Systems Assessment: Issues and

Challenges (Bjorn-Anderson N and Davis GB, Eds), pp 41–52.

Hagmann C and McCahon C (1993) Strategic information systems

and competitiveness. Information and Management 25, 183–192.

Hashmi MS and Cuddy J (1990) Strategic initiatives for introducing

CIM technologies in Irish SMEs. In Computer Integrated Manufac-

turing—Proceedings of the 6th CIM-Europe Annual Conference

(Faria L, Ed), 15–17 May 1990, Lisbon, Portugal, Van Puym-

broeck, Springer Verlag.

Appendix A

Company A Company B Company C Company D

Strategy Production and Production oriented Production oriented Production and

performance oriented performance oriented

Structure Managing Director Senior manager Senior manager Senior manager

responsible for responsible for responsible for responsible for

purchasing. purchasing. purchasing. purchasing.

Operations manager No internal IS No internal IS Part-time programmer

responsible for on-going organization organisation for additional systems

systems development development.

Systems MRP package MRP package purchased MRP package MRP package

purchased; only partially and developed with purchased; only purchased; only

implemented. Interface small software supplier partially partially

being developed with implemented. implemented.

estimating system Spreadsheet software Spreadsheet software

available but not available but not

integrated integrated

Hirschheim R and Smithson S (1988) A critical analysis of infor-

mation systems evaluation. In Information Systems Assessment:

Issues and Challenges (Bjorn-Anderson N and Davis GB, eds),

pp 17–37, Oxford, North Holland, Amsterdam.

Hochstrasser B (1992) Justifying IT Investments. Advanced Infor-

mation Systems, The New Technologies in Today’s Business

Environment, Proceedings, 17–28.

Lederer AL and Mendelow A (1986) Issues in information systems

planning. Information and Management 10, 245–254.

Mintzberg H (1983) Structure in Fives: Designing Effective Organis-

ations. Prentice Hall International Inc, Englewood Cliffs, New Jer-

sey.

NatWest Review of Small Business Trends (1992) Small Business

Trust 2(1), xii.

Niederman F, Brancheau JC and Wetherbe JC (1991) Information

Systems Management Issues for the 1990’s. MIS Quarterly 15(4),

475–499.

Pascale RT and Athos AG (1981) The Art of Japanese Management.

Penguin, Harmondsworth.

Parker MM, Trainor HE and Benson RJ (1989) Information Strat-

egy and Economics. Prentice-Hall, US.

Powell P (1992) IT Evaluation: Is It Different? Journal of the Oper-

ations Research Society 43(1), 29–42.

Price Waterhouse (1992) Information Technology Review

1991/92, London.

Storey DJ and Cressy R (1995) Small Business Risk: A Firm and

Bank Perspective. Working Paper. SME Centre, Warwick Busi-

ness School.

Storey DJ (1995) Understanding the Small Business Sector. Rout-

ledge, London.

Symons V and Walsham G (1988) The Evaluation of Information

Systems: A Critique. Journal of Applied Systems Analysis 15,

119–132.

Tam KY (1992) Capital budgeting in information systems develop-

ment. Information and Management 23, 345–357.

Willcocks L (1992) Evaluating information technology investments,

research findings and reappraisal. Journal of Information Systems 2,

243–268.

Zuboff S (1988) The Age of the Smart Machine. Heinemann Pro-

fessional Publishing, Oxford, UK.