The Effect of Microstructure and Environment

on Fatigue Crack Closure of 7475 Aluminum Alloy

R.D. CARTER, E.W. LEE, E.A. STARKE, Jr., and C.J. BEEVERS

The effects of slip character and grain size on the intrinsic material and extrinsic closure contributions

to fatigue crack growth resistance have been studied for a 7475 aluminum alloy. The alloy was tested

in the underaged and overaged conditions with grain sizes of 18/xm and 80/xm. The fracture surface

exhibited increased irregularity and planar facet formation with increased grain size, underaging, and

tests in vacuum. These changes were accompanied by an increased resistance to fatigue crack growth.

In air the 18/xm grain size overaged material exhibited relatively poor resistance to fatigue crack

growth compared with other microstructural variants, and this was associated with a lower stress

intensity for closure. All materials exhibited a marked improvement in fatigue crack growth resistance

when tested in vacuum, with the most significant difference being -1000• at a AK of 10 MPa m v2

for the 80/xm grain size underaged alloy. This improvement could not be accounted for by either

an increase in closure or increased crack deflection and is most likely due to increased slip reversi-

bility in the vacuum environment. The intrinsic resistance of the alloy to fatigue crack growth

was microstructurally dependent in vacuum, with large grains and planar slip providing the better

fatigue performance.

I. INTRODUCTION

TRADITIONAL design of cyclically loaded components

utilizes the fatigue endurance limit: a parameter experi-

'mentally determined using defect-free samples, l Lately,

fracture mechanics concepts have been used in conjunction

with nondestructive measurements of defects to establish the

maximum cyclic stress below which a detectable crack will

not grow. 2'3 The resulting design parameter used for the

preexisting defect tolerant approach is the threshold stress

intensity range, AK~. Recent studies have shown that the

magnitude of this experimentally determined parameter can

be greatly influenced by closure effects. Elber 4 pointed out

the existence of crack closure in 1970 when he observed that

a crack in a fatigue specimen was closed during a portion

of the loading cycle, even when the minimum load was

tensile. Since crack closure always gives a positive effect,

i.e.,

it reduces fatigue crack growth rates, there is con-

siderable interest in identifying the mechanisms associated

with closure.

Fatigue crack closure was considered by early researchers

to be only a plane stress phenomenon 5 caused by the re-

straint of elastic material surrounding permanent plastic ten-

sile deformation left in the wake of the propagating crack, 4

and was termed "plasticity-induced crack closure. ''6 Later,

crack closure was found to be significant in thick specimens

under plane strain conditions, and attributed to crack

branching and Mode II displacements. 7 Closure resulting

from mode II displacements requires a rough or uneven

fracture surface and is termed "roughness-induced crack

closure. ''6 An oxidizing environment may also influence

closure behavior, and Ritchie and Suresh 8 suggest that

R. D. CARTER is an Engineer, United States Army Corps of Engineers,

P.O. Box 61, Tulsa, OK 74121. E. W. LEE is a Postdoctoral Fellow, Frac-

ture and Fatigue Research Laboratory, Georgia Institute of Technology,

Atlanta, GA 30332. E.A. STARKE, Jr. is Earnest Oglesby Professor

of Materials Science, Department of Materials Science, University of

Virginia, Charlottesville, VA 22901. C.J. BEEVERS is Professor,

Department of Metallurgy and Materials, University of Birmingham,

Birmingham B15 2TT, England.

Manuscript submitted August 15, 1983.

"oxide-induced crack closure" may occur during low crack

growth rates where sufficient time is allowed for the for-

mation of thick oxide layer which prevents the crack from

closing when the load is removed.

Since closure reduces crack propagation rates it is of

practical importance to determine those parameters which

enhance its occurrence. Slip length and slip behavior have

been shown to influence both the fracture path (crack

branching and surface roughness) and environmental sensi-

tivity of fatigue crack growth. 9-~2 The purpose of this study

was to investigate the roughness-induced and oxide-induced

crack closure behavior of 7475 aluminum alloy under differ-

ent microstructural and environmental conditions. Emphasis

was placed on the effect of grain size and deformation mode

on crack closure of compact tension samples subjected to

plane strain conditions in a vacuum and in a laboratory

air environment.

II. EXPERIMENTAL

The 7475 alloy used in this research was obtained as

2.5 inch thick plate from the Alcoa Technical Center. The

chemical composition in weight percent is given in Table I.

Starting with the 2.5 inch thick plate, two different inter-

mediate thermomechanical treatments (ITMT's), shown

schematically in Figure 1, were used to obtain the desired

grain structure. They include solutionizing, overaging,

warm rolling, and recrystallization treatments. The large

particles (-1 /xm diameter) that result from the overaging

treatment create strain concentrations during the warm roll-

ing, and these deformation zones act as nucleation sites for

recrystallization. 13 Small grains were obtained by using a

large amount of deformation and rapid heating to the re-

crystallization temperature (Figure l(a)). Large grains were

obtained by using a small amount of deformation and slow

heating to the recrystallization temperature (Figure l(b)).

All heat treatments were conducted in a molten nitride salt

bath except those associated with the rolling operation

which were conducted in an electric air furnace. Samples

METALLURGICAL TRANSACTIONS A VOLUME 15A, MARCH 1984--555

o•500

w 400

E~

~

300

n,-

w 200

w

I- 100

SOLUTIONIZE (485C)

m

i i i i i

4 8 12

TIME

RECRYSTALLIZE (485C)

SEVERE OVERAGE

I I I I I I I

16 20 24 28 32

(hr)

(a)

TIME (hr)

(b)

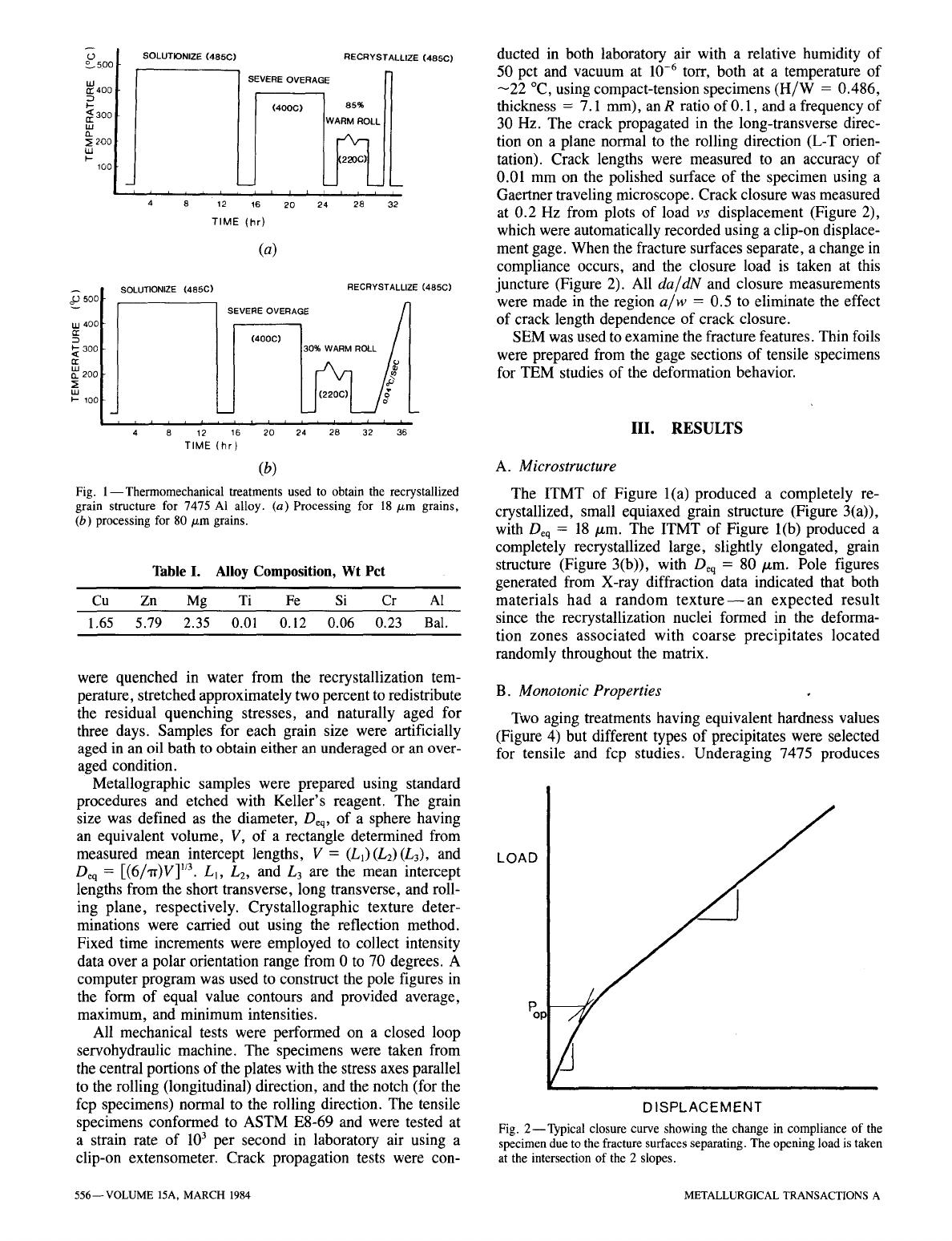

Fig. 1--Thermomechanical treatments used to obtain the recrystallized

grain structure for 7475 AI alloy. (a) Processing for 18/xm grains,

(b) processing for 80/zm grains.

SOLUTIONIZE (485C) RECRYSTALLIZE (485C)

SEVERE OVERAGE

.ooc, I /

7

i i i t I i 1 i i i i 218 i 2 / i

4 8 12 16 20 24 3 36

Table I. Alloy Composition, Wt Pct

B. Monotonic Properties

Cu Zn Mg Ti Fe Si Cr A1

1.65 5.79 2.35 0.01 0.12 0.06 0.23 Bal.

were quenched in water from the recrystallization tem-

perature, stretched approximately two percent to redistribute

the residual quenching stresses, and naturally aged for

three days. Samples for each grain size were artificially

aged in an oil bath to obtain either an underaged or an over-

aged condition.

Metallographic samples were prepared using standard

procedures and etched with Keller's reagent. The grain

size was defined as the diameter, Deq, of a sphere having

an equivalent volume, V, of a rectangle determined from

measured mean intercept lengths, V = (L1)(L2)(L3), and

Oeq :

[(6/'tr)V] 1/3.

LI, L2, and L 3 are the mean intercept

lengths from the short transverse, long transverse, and roll-

ing plane, respectively. Crystallographic texture deter-

minations were carried out using the reflection method.

Fixed time increments were employed to collect intensity

data over a polar orientation range from 0 to 70 degrees. A

computer program was used to construct the pole figures in

the form of equal value contours and provided average,

maximum, and minimum intensities.

All mechanical tests were performed on a closed loop

servohydraulic machine. The specimens were taken from

the central portions of the plates with the stress axes parallel

to the rolling (longitudinal) direction, and the notch (for the

fcp specimens) normal to the rolling direction. The tensile

specimens conformed to ASTM E8-69 and were tested at

a strain rate of 103 per second in laboratory air using a

clip-on extensometer. Crack propagation tests were con-

ducted in both laboratory air with a relative humidity of

50 pct and vacuum at

10 -6 tOIT,

both at a temperature of

-22 ~ using compact-tension specimens (H/W = 0.486,

thickness = 7.1 mm), an R ratio of 0.1, and a frequency of

30 Hz. The crack propagated in the long-transverse direc-

tion on a plane normal to the rolling direction (L-T orien-

tation). Crack lengths were measured to an accuracy of

0.01 mm on the polished surface of the specimen using a

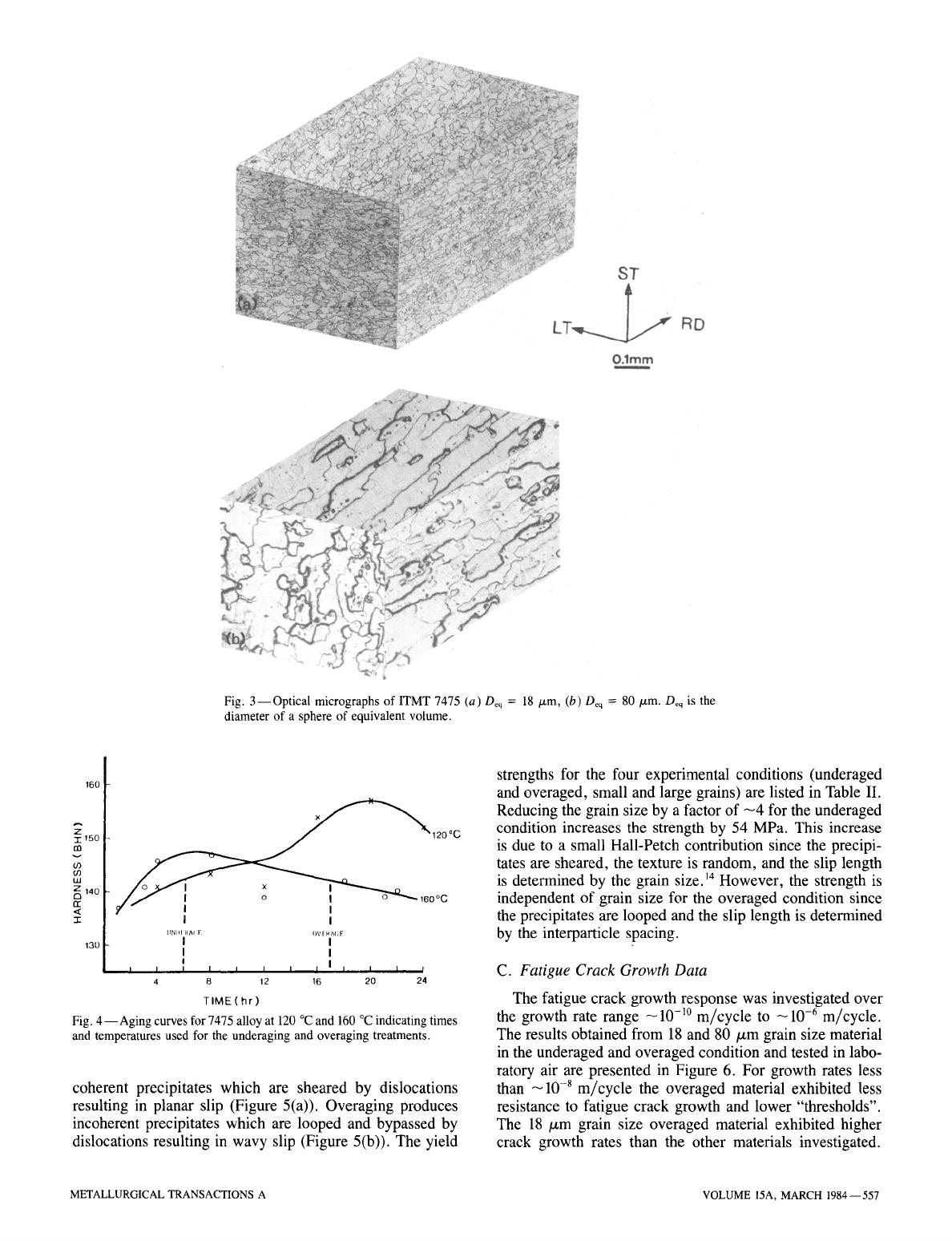

Gaertner traveling microscope. Crack closure was measured

at 0.2 Hz from plots of load vs displacement (Figure 2),

which were automatically recorded using a clip-on displace-

ment gage. When the fracture surfaces separate, a change in

compliance occurs, and the closure load is taken at this

juncture (Figure 2). All da/dN and closure measurements

were made in the region a/w = 0.5 to eliminate the effect

of crack length dependence of crack closure.

SEM was used to examine the fracture features. Thin foils

were prepared from the gage sections of tensile specimens

for TEM studies of the deformation behavior.

III. RESULTS

A. Microstructure

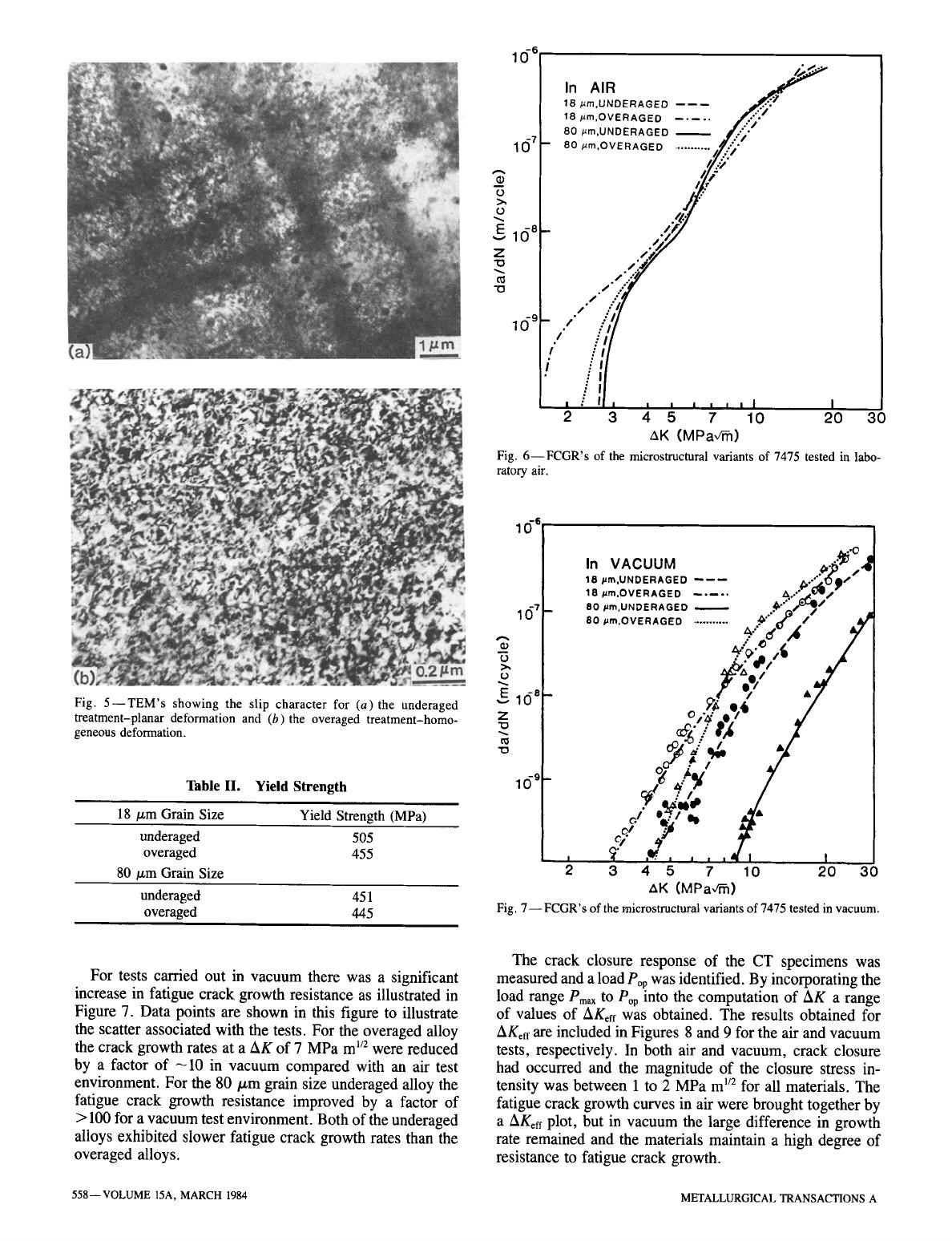

The ITMT of Figure l(a) produced a completely re-

crystallized, small equiaxed grain structure (Figure 3(a)),

with Deq = 18/zm. The ITMT of Figure l(b) produced a

completely recrystallized large, slightly elongated, grain

structure (Figure 3(b)), with Deq = 80/xm. Pole figures

generated from X-ray diffraction data indicated that both

materials had a random texture--an expected result

since the recrystallization nuclei formed in the deforma-

tion zones associated with coarse precipitates located

randomly throughout the matrix.

LOAD

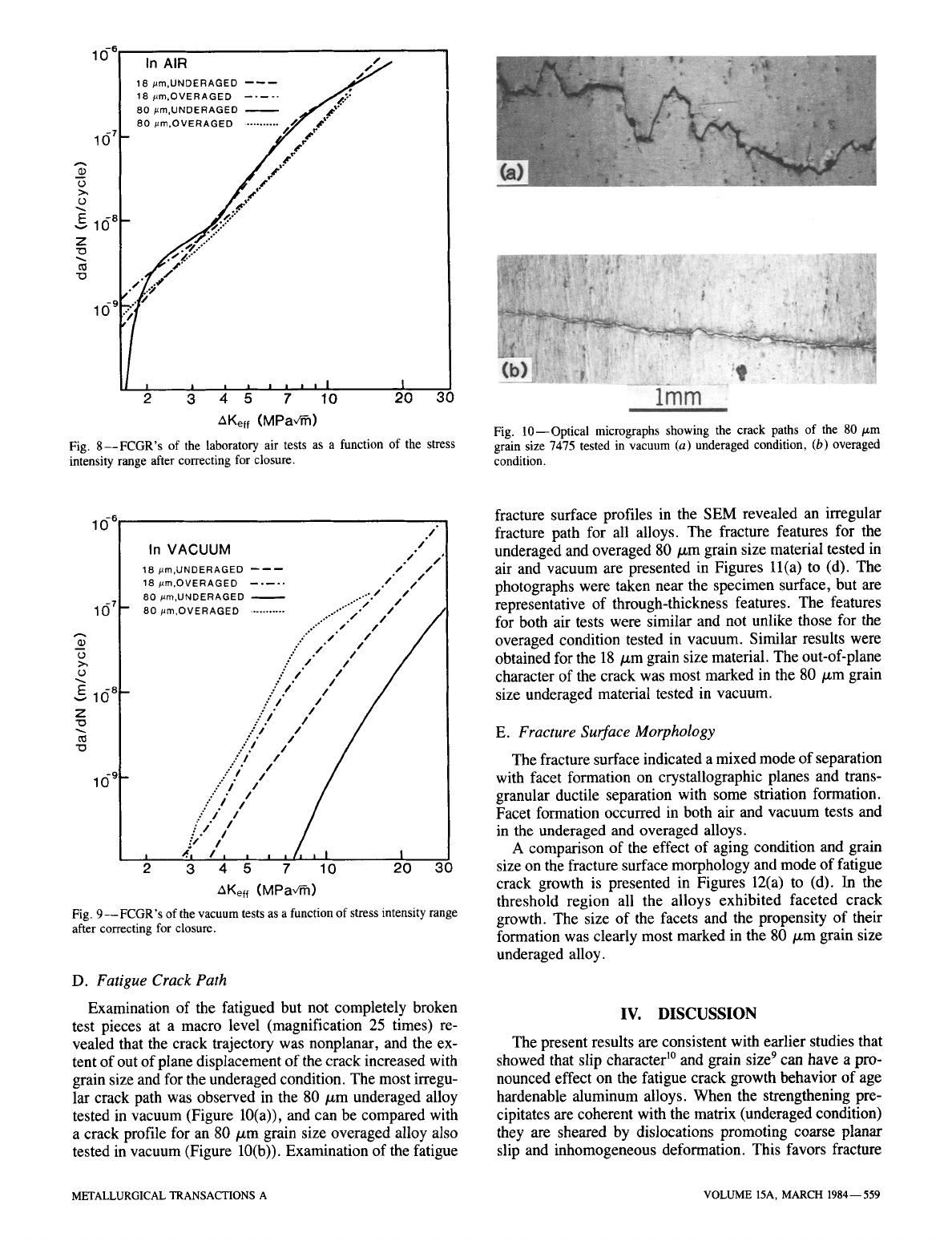

Two aging treatments having equivalent hardness values

(Figure 4) but different types of precipitates were selected

for tensile and fcp studies. Underaging 7475 produces

I

%

~

w

CI~ 400

:3

I--

C~..< 300

W

t~

3~ 200

I,.-

100

DISPLACEMENT

Fig. 2--Typical closure curve showing the change in compliance of the

specimen due to the fracture surfaces separating. The opening load is taken

at the intersection of the 2 slopes.

556--VOLUME 15A, MARCH 1984 METALLURGICAL TRANSACTIONS A

Fig. 3--Optical micrographs of ITMT 7475 (a) Deq = 18 p.m, (b) Deq = 80/zm. Deq is the

diameter of a sphere of equivalent volume.

160

Z

120oC

3Z150

co

w

~

140

rr

< I

-1- I I

UN[I~

[IAI [:

()V[ RA(;E

I I

130

I I

I I ~ I I I I I I I I I I

a

4

8 12

16

20 24

TIME(hr)

Fig. 4--Aging curves for 7475 alloy at 120 ~ and 160 ~ indicating times

and temperatures used for the underaging and overaging treatments.

coherent precipitates which are sheared by dislocations

resulting in planar slip (Figure 5(a)). Overaging produces

incoherent precipitates which are looped and bypassed by

dislocations resulting in wavy slip (Figure 5(b)). The yield

strengths for the four experimental conditions (underaged

and overaged, small and large grains) are listed in Table II.

Reducing the grain size by a factor of -4 for the underaged

condition increases the strength by 54 MPa. This increase

is due to a small Hall-Petch contribution since the precipi-

tates are sheared, the texture is random, and the slip length

is determined by the grain size. 14 However, the strength is

independent of grain size for the overaged condition since

the precipitates are looped and the slip length is determined

by the interparticle spacing.

C. Fatigue Crack Growth Data

The fatigue crack growth response was investigated over

the growth rate range -10 -1~ m/cycle to

~10 -6

m/cycle.

The results obtained from 18 and 80/xm grain size material

in the underaged and overaged condition and tested in labo-

ratory air are presented in Figure 6. For growth rates less

than -10 -8 m/cycle the overaged material exhibited less

resistance to fatigue crack growth and lower "thresholds".

The 18/zm grain size overaged material exhibited higher

crack growth rates than the other materials investigated.

METALLURGICAL TRANSACTIONS A VOLUME 15A, MARCH 1984--557

10- 6

16 7

A

o

o

v E I(~ 8

Z

"0

"o

In AIR

18 #m,UNDERAGED mm

18 #m,OVERAGED

80 #m,UNDERAGED

80#m,OVERAGED

/

f ~ ,,

' : ' I

m

I

,

, I I I

2 3 4 5 7 10 20 30

,&K (MPa,/~)

Fig. 6--FCGR's of the microstructural variants of 7475 tested in labo-

ratory air.

Fig. 5--TEM's showing the slip character for (a)the underaged

treatment-planar deformation and (b)the overaged treatment-homo-

geneous deformation.

Table II. Yield

Strength

18/zm Grain Size Yield Strength (MPa)

underaged 505

overaged 455

80/zm Grain Size

underaged 451

overaged 445

1 1~61

In VACUUM ~,. "~':,~

18/,tm,UNDERAGED ~--~ ~.-'~:);~'

18 /~m.OVERAGED ..... ,~, ...~Jw/--

80 /arn,UNDERAGED ~"::,/~/I

16

"t

- 80 ~,OvE~,AGEO

........... .*" ~ ,"

Av =

f;.,,

.r

E 16a-

"" o ~',g e,6

Z /d_e"

=- ~ / tA ,/

J'f ,

~f ,~ , , , , 41 t

3 4 5 7 10 20 30

AK (MPaV~)

Fig, 7--FCGR's of the microstructural variants of 7475 tested in vacuum.

For tests carried out in vacuum there was a significant

increase in fatigue crack growth resistance as illustrated in

Figure 7. Data points are shown in this figure to illustrate

the scatter associated with the tests. For the overaged alloy

the crack growth rates at a AK of 7 MPa m 1/2 were reduced

by a factor of -10 in vacuum compared with an air test

environment. For the 80/xm grain size underaged alloy the

fatigue crack growth resistance improved by a factor of

> 100 for a vacuum test environment. Both of the underaged

alloys exhibited slower fatigue crack growth rates than the

overaged alloys.

The crack closure response of the CT specimens was

measured and a load Pop was identified. By incorporating the

load range

Pmax

to Pop into the computation of AK a range

of values of AKoff was obtained. The results obtained for

AKeff are included in Figures 8 and 9 for the air and vacuum

tests, respectively. In both air and vacuum, crack closure

had occurred and the magnitude of the closure stress in-

tensity was between 1 to 2 MPa m 1/2 for all materials. The

fatigue crack growth curves in air were brought together by

a AKeff plot, but in vacuum the large difference in growth

rate remained and the materials maintain a high degree of

resistance to fatigue crack growth.

558--VOLUME 15A, MARCH 1984 METALLURGICAL TRANSACTIONS A

ld 6

16 7

0

>,

0

16 8

Z

"O

15 g

In AIR

18 #m,UNDERAGED ------ ~"~"

18 ,arn.OVER A G ED ..... :..'-;

80 #m.UNDERAGED

80 ,um,OVERAGED ........... ,

,,.,-

,,.,-

,,.,-

~,Y

#,.

/..'."

~.'..

~/..."

./.

, , , , ,I I

) 3 7 lo 2o

AKeff (MPav~)

30

Fig. 8--FCGR's of the laboratory air tests as a function of the stress

intensity range after correcting for closure.

Fig. 10--Optical micrographs showing the crack paths of the 80/~m

grain size 7475 tested in vacuum (a) underaged condition, (b) overaged

condition.

10-6 In VACUUM

/.//~,]

18 ,um,UNDERAGED ------ /" / I

18 #m OVERAGED .....

/'"

// I

' ./ /

80 #rn,UNDERAGED ..-'" 9 . I

1 (~7 80 #m,OVERAGED ........... . ....... ".'/ /" 13

.-'""

i'' // /

_

"

/" //

/

~

/

(.)

:."

/./ //

~. ." . / /

// /

E

16 6 .'

/ /

/

"0

.:

/ /

.-'/" /

1 () 9 / " /

.:/.I //

::

i.I

ii ]l

-"/"

I /

./ i I

l

I ~'I /I I

, , , ~

I I

2 3 4 5 7 10 20 30

AKeff (MPa,/~)

Fig. 9-- FCGR's of the vacuum tests as a function of stress intensity range

after correcting for closure.

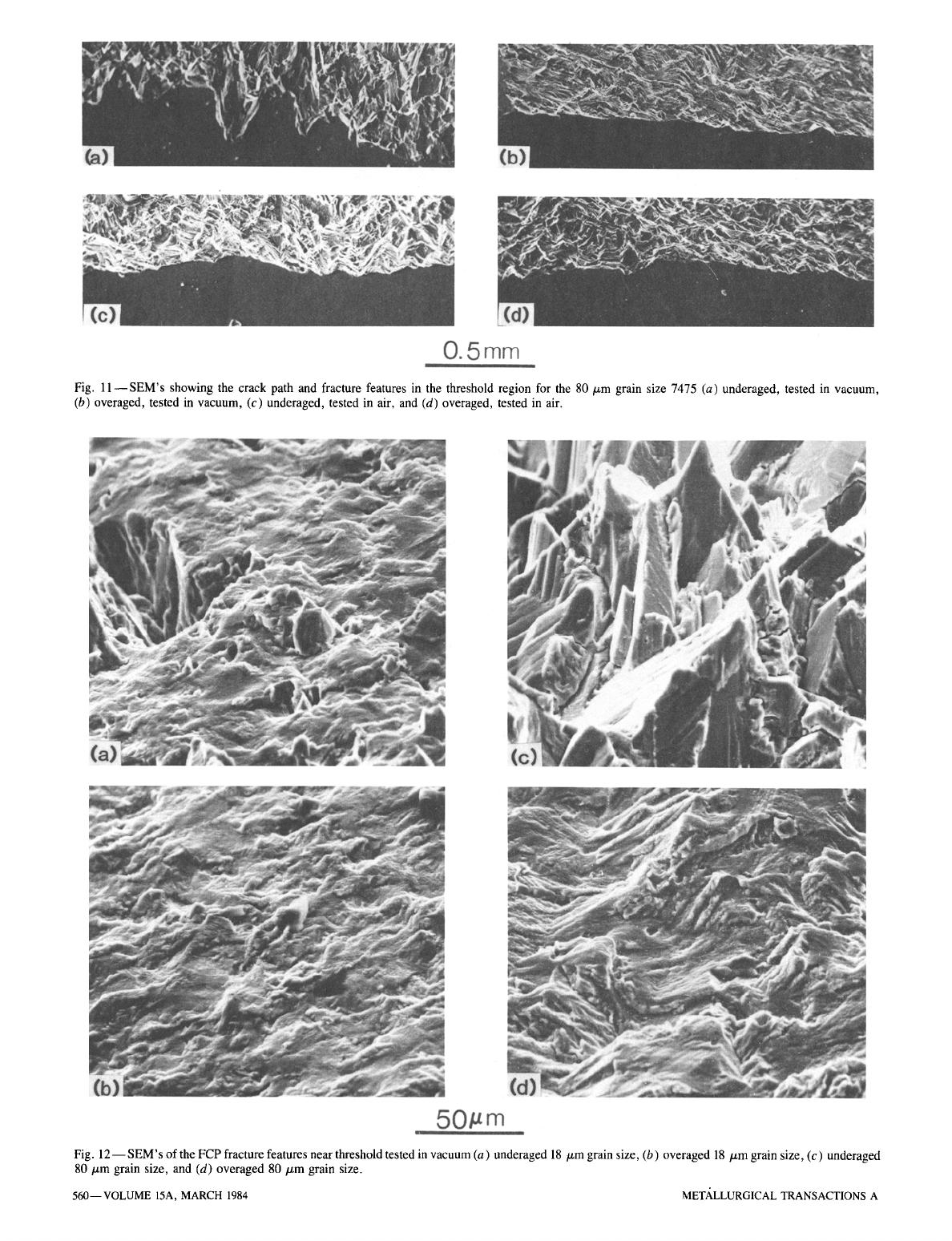

D. Fatigue Crack Path

Examination of the fatigued but not completely broken

test pieces at a macro level (magnification 25 times) re-

vealed that the crack trajectory was nonplanar, and the ex-

tent of out of plane displacement of the crack increased with

grain size and for the underaged condition. The most irregu-

lar crack path was observed in the 80/.~m underaged alloy

tested in vacuum (Figure 10(a)), and can be compared with

a crack profile for an 80/~m grain size overaged alloy also

tested in vacuum (Figure 10(b)). Examination of the fatigue

fracture surface profiles in the SEM revealed an irregular

fracture path for all alloys. The fracture features for the

underaged and overaged 80/zm grain size material tested in

air and vacuum are presented in Figures ll(a) to (d). The

photographs were taken near the specimen surface, but are

representative of through-thickness features. The features

for both air tests were similar and not unlike those for the

overaged condition tested in vacuum. Similar results were

obtained for the 18/xm grain size material. The out-of-plane

character of the crack was most marked in the 80/~m grain

size underaged material tested in vacuum.

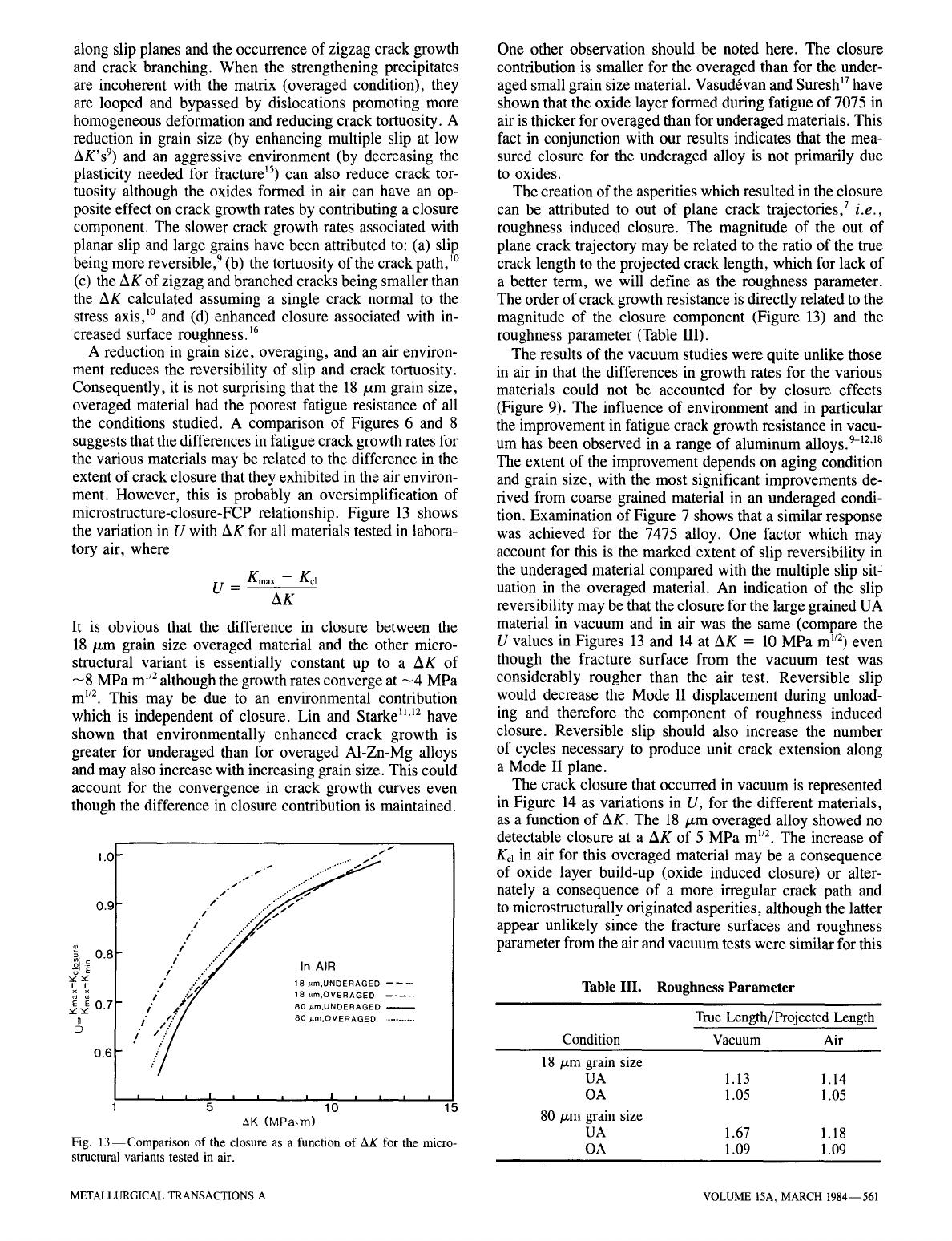

E. Fracture Surface Morphology

The fracture surface indicated a mixed mode of separation

with facet formation on crystallographic planes and trans-

granular ductile separation with some striation formation.

Facet formation occurred in both air and vacuum tests and

in the underaged and overaged alloys.

A comparison of the effect of aging condition and grain

size on the fracture surface morphology and mode of fatigue

crack growth is presented in Figures 12(a) to (d). In the

threshold region all the alloys exhibited faceted crack

growth. The size of the facets and the propensity of their

formation was clearly most marked in the 80/~m grain size

underaged alloy.

IV. DISCUSSION

The present results are consistent with earlier studies that

showed that slip character 1~ and grain size 9 can have a pro-

nounced effect on the fatigue crack growth behavior of age

hardenable aluminum alloys. When the strengthening pre-

cipitates are coherent with the matrix (underaged condition)

they are sheared by dislocations promoting coarse planar

slip and inhomogeneous deformation. This favors fracture

METALLURGICAL TRANSACTIONS A VOLUME 15A, MARCH 1984--559

Fig. 11--SEM's showing the crack path and fracture features in the threshold region for the 80/zm grain size 7475 (a) underaged, tested in vacuum,

(b) overaged, tested in vacuum, (c) underaged, tested in air, and (d) overaged, tested in air.

Fig. 12-- SEM's of the FCP fracture features near threshold tested in vacuum (a) underaged 18 ~m grain size, (b) overaged 18/zm grain size, (c) underaged

80/zm grain size, and (d) overaged 80/~m grain size.

560--VOLUME 15A, MARCH 1984 METALLURGICAL TRANSACTIONS A

along slip planes and the occurrence of zigzag crack growth

and crack branching. When the strengthening precipitates

are incoherent with the matrix (overaged condition), they

are looped and bypassed by dislocations promoting more

homogeneous deformation and reducing crack tortuosity. A

reduction in grain size (by enhancing multiple slip at low

AK's 9)

and an aggressive environment (by decreasing the

plasticity needed for fracture 15) can also reduce crack tor-

tuosity although the oxides formed in air can have an op-

posite effect on crack growth rates by contributing a closure

component9 The slower crack growth rates associated with

planar slip and large grains have been attributed to: (a) slip

being more reversible, 9 (b) the tortuosity of the crack path, 10

(c) the AK of zigzag and branched cracks being smaller than

the AK calculated assuming a single crack normal to the

stress axis, l~ and (d) enhanced closure associated with in-

creased surface roughness. 16

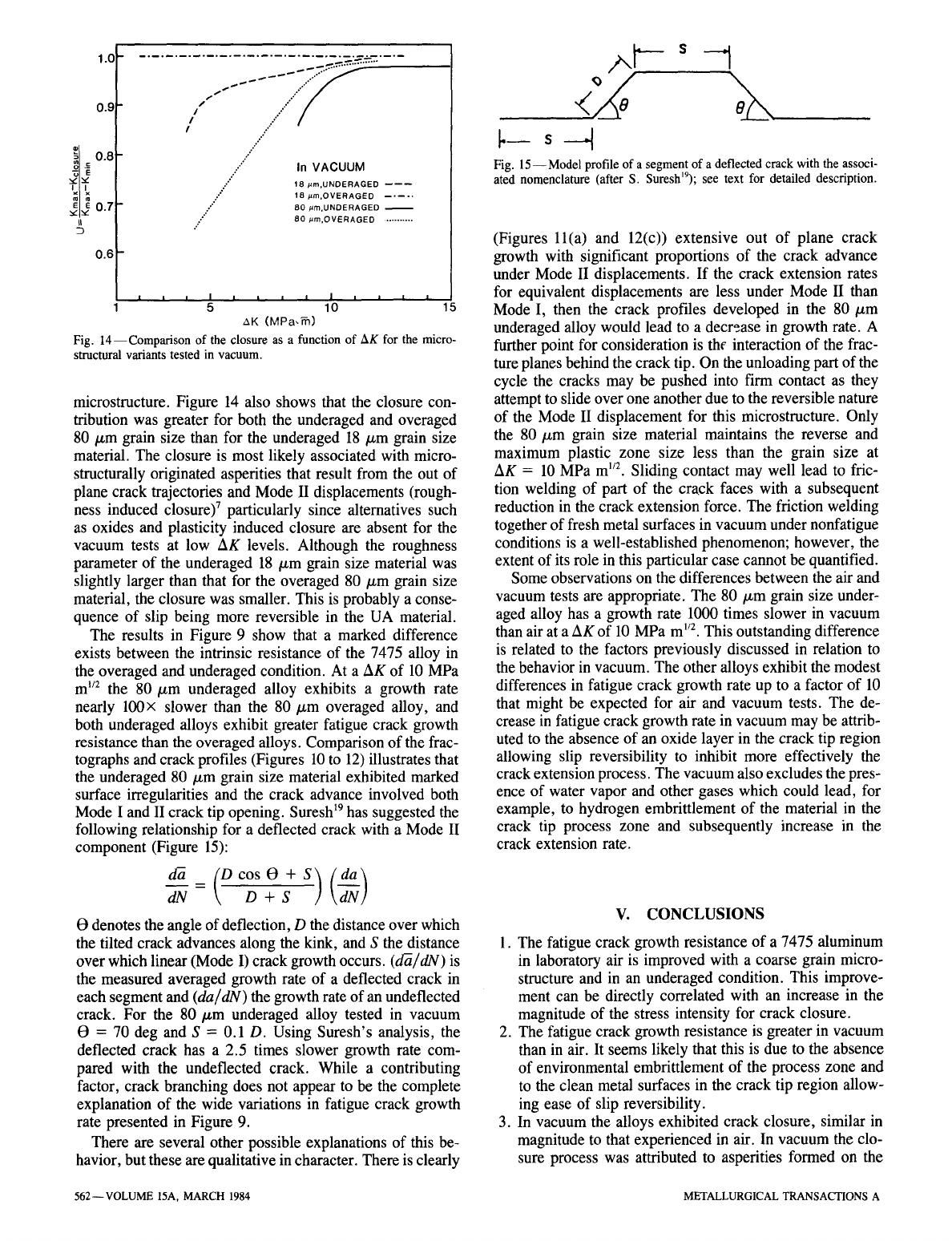

A reduction in grain size, overaging, and an air environ-

ment reduces the reversibility of slip and crack tortuosity.

Consequently, it is not surprising that the 18/zm grain size,

overaged material had the poorest fatigue resistance of all

the conditions studied. A comparison of Figures 6 and 8

suggests that the differences in fatigue crack growth rates for

the various materials may be related to the difference in the

extent of crack closure that they exhibited in the air environ-

ment. However, this is probably an oversimplification of

microstructure-closure-FCP relationship. Figure 13 shows

the variation in U with AK for all materials tested in labora-

tory air, where

Kmax --

Kcl

U-

AK

It is obvious that the difference in closure between the

18/zm grain size overaged material and the other micro-

structural variant is essentially constant up to a AK of

--8 MPa m 1/2 although the growth rates converge at -4 MPa

m 1/2. This may be due to an environmental contribution

which is independent of closure. Lin and Starke

TM

have

shown that environmentally enhanced crack growth is

greater for underaged than for overaged AI-Zn-Mg alloys

and may also increase with increasing grain size. This could

account for the convergence in crack growth curves even

though the difference in closure contribution is maintained9

lO f

,, 0.9

0.8

II

D

0.6

/

i" ..'"

9 ,.....

.I ... ~"

i I 9

/'/ ."'7 In AIR

i ~"://"~ 18 #m,UNOERAGED --~--

/" ,.-~/ 18 #m:OVERAGED .....

i ~'/~/ 80 #m,UNDERAGED

9

/.: 80 /~m,OVERAGED ~ 80 /~m,OVERAGED

...........

./ /..."

./

I I I I I I I I I I I I I

5 10 15

AK (MPa~)

Fig. 13--Comparison of the closure as a function of AK for the micro-

structural variants tested in air.

One other observation should be noted here. The closure

contribution is smaller for the overaged than for the under-

aged small grain size material. Vasudrvan and Suresh 17 have

shown that the oxide layer formed during fatigue of 7075 in

air is thicker for overaged than for underaged materials. This

fact in conjunction with our results indicates that the mea-

sured closure for the underaged alloy is not primarily due

to oxides9

The creation of the asperities which resulted in the closure

can be attributed to out of plane crack trajectories, 7

i.e.,

roughness induced closure. The magnitude of the out of

plane crack trajectory may be related to the ratio of the true

crack length to the projected crack length, which for lack of

a better term, we will define as the roughness parameter.

The order of crack growth resistance is directly related to the

magnitude of the closure component (Figure 13) and the

roughness parameter (Table III).

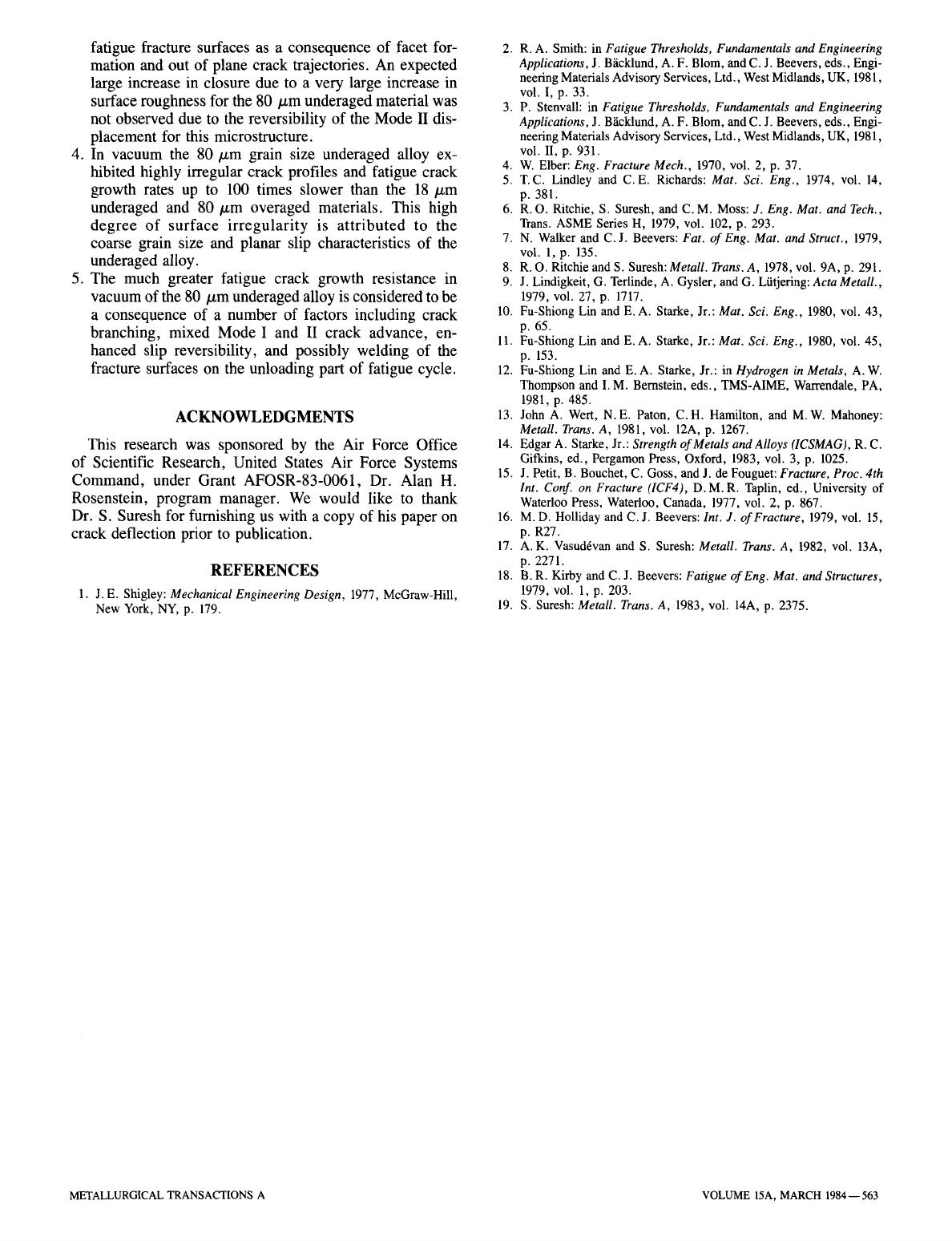

The results of the vacuum studies were quite unlike those

in air in that the differences in growth rates for the various

materials could not be accounted for by closure effects

(Figure 9). The influence of environment and in particular

the improvement in fatigue crack growth resistance in vacu-

um has been observed in a range of aluminum alloys. 9-1z'18

The extent of the improvement depends on aging condition

and grain size, with the most significant improvements de-

rived from coarse grained material in an underaged condi-

tion. Examination of Figure 7 shows that a similar response

was achieved for the 7475 alloy. One factor which may

account for this is the marked extent of slip reversibility in

the underaged material compared with the multiple slip sitZ

uation in the overaged material. An indication of the slip

reversibility may be that the closure for the large grained UA

material in vacuum and in air was the same (compare the

U values in Figures 13 and 14 at AK = 10 MPa m 1/2) even

though the fracture surface from the vacuum test was

considerably rougher than the air test. Reversible slip

would decrease the Mode II displacement during unload-

ing and therefore the component of roughness induced

closure. Reversible slip should also increase the number

of cycles necessary to produce unit crack extension along

a Mode II plane.

The crack closure that occurred in vacuum is represented

in Figure 14 as variations in U, for the different materials,

as a function of AK. The 18 /xm overaged alloy showed no

detectable closure at a AK of 5 MPa m ~/2. The increase of

Kcl in air for this overaged material may be a consequence

of oxide layer build-up (oxide induced closure) or alter-

nately a consequence of a more irregular crack path and

to microstructurally originated asperities, although the latter

appear unlikely since the fracture surfaces and roughness

parameter from the air and vacuum tests were similar for this

Table IlL Roughness Parameter

True Length/Projected Length

Condition Vacuum Air

18/xm grain size

UA 1.13 1.14

OA 1.05 1.05

80 p,m grain size

UA 1.67 1.18

OA 1.09 1.09

METALLURGICAL TRANSACTIONS A VOLUME 15A, MARCH 1984--561

0.91.0

1 .............................. /, ,, ~.~ ~_ ~ i.~.~,~.~'--~- ....

i~ 0.8

o .-

"6 E

x x

m m

E E0. 7

D

0.6

l

..." In VACUUM

.,'

18 #m.UNDERAGED

----~

18 .am.OVERAGED

.," 80 #m.UNDERAGED

:." 80 #m,OVERAGED

...........

I | i i i I i

5 10

AK (MPa,~)

Fig. 14--Comparison of the closure as a function of AK for the micro-

structural variants tested in vacuum.

microstructure. Figure 14 also shows that the closure con-

tribution was greater for both the underaged and overaged

80 #m grain size than for the underaged 18/xm grain size

material. The closure is most likely associated with micro-

structurally originated asperities that result from the out of

plane crack trajectories and Mode II displacements (rough-

ness induced closure) 7 particularly since alternatives such

as oxides and plasticity induced closure are absent for the

vacuum tests at low AK levels. Although the roughness

parameter of the underaged 18/xm grain size material was

slightly larger than that for the overaged 80/zm grain size

material, the closure was smaller. This is probably a conse-

quence of slip being more reversible in the UA material.

The results in Figure 9 show that a marked difference

exists between the intrinsic resistance of the 7475 alloy in

the overaged and underaged condition. At a AK of 10 MPa

m 1/2 the 80/~m underaged alloy exhibits a growth rate

nearly 100x slower than the 80/xm overaged alloy, and

both underaged alloys exhibit greater fatigue crack growth

resistance than the overaged alloys. Comparison of the frac-

tographs and crack profiles (Figures 10 to 12) illustrates that

the underaged 80/xm grain size material exhibited marked

surface irregularities and the crack advance involved both

Mode I and II crack tip opening.

Suresh ~9

has suggested the

following relationship for a deflected crack with a Mode II

component (Figure 15):

-~ D+ S

t9 denotes the angle of deflection, D the distance over which

the tilted crack advances along the kink, and S the distance

over which linear (Mode I) crack growth occurs. (d~/dN) is

the measured averaged growth rate of a deflected crack in

each segment and

(da/dN)

the growth rate of an undeflected

crack. For the 80/zm underaged alloy tested in vacuum

19 = 70 deg and S = 0.1 D. Using Suresh's analysis, the

deflected crack has a 2.5 times slower growth rate com-

pared with the undeflected crack. While a contributing

factor, crack branching does not appear to be the complete

explanation of the wide variations in fatigue crack growth

rate presented in Figure 9.

There are several other possible explanations of this be-

havior, but these are qualitative in character. There is clearly

s J

I

Fig. 15--Model profile of a segment of a deflected crack with the associ-

ated nomenclature (after S. Sureshl9); see text for detailed description.

(Figures ll(a) and 12(c)) extensive out of plane crack

growth with significant proportions of the crack advance

under Mode II displacements. If the crack extension rates

for equivalent displacements are less under Mode II than

Mode I, then the crack profiles developed in the 80/zm

underaged alloy would lead to a decrease in growth rate. A

further point for consideration is the interaction of the frac-

ture planes behind the crack tip. On the unloading part of the

cycle the cracks may be pushed into firm contact as they

attempt to slide over one another due to the reversible nature

of the Mode II displacement for this microstructure. Only

the 80/xm grain size material maintains the reverse and

maximum plastic zone size less than the grain size at

AK = 10 MPa m '/2. Sliding contact may well lead to fric-

tion welding of part of the crack faces with a subsequent

reduction in the crack extension force. The friction welding

together of fresh metal surfaces in vacuum under nonfatigue

conditions is a well-established phenomenon; however, the

extent of its role in this particular case cannot be quantified.

Some observations on the differences between the air and

vacuum tests are appropriate. The 80/~m grain size under-

aged alloy has a growth rate 1000 times slower in vacuum

than air at a AK of 10 MPa m 1/2. This outstanding difference

is related to the factors previously discussed in relation to

the behavior in vacuum. The other alloys exhibit the modest

differences in fatigue crack growth rate up to a factor of 10

that might be expected for air and vacuum tests. The de-

crease in fatigue crack growth rate in vacuum may be attrib-

uted to the absence of an oxide layer in the crack tip region

allowing slip reversibility to inhibit more effectively the

crack extension process. The vacuum also excludes the pres-

ence of water vapor and other gases which could lead, for

example, to hydrogen embrittlement of the material in the

crack tip process zone and subsequently increase in the

crack extension rate.

V. CONCLUSIONS

1. The fatigue crack growth resistance of a 7475 aluminum

in laboratory air is improved with a coarse grain micro-

structure and in an underaged condition. This improve-

ment can be directly correlated with an increase in the

magnitude of the stress intensity for crack closure.

2. The fatigue crack growth resistance is greater in vacuum

than in air. It seems likely that this is due to the absence

of environmental embrittlement of the process zone and

to the clean metal surfaces in the crack tip region allow-

ing ease of slip reversibility.

3. In vacuum the alloys exhibited crack closure, similar in

magnitude to that experienced in air. In vacuum the clo-

sure process was attributed to asperities formed on the

562--VOLUME 15A, MARCH 1984 METALLURGICAL TRANSACTIONS A

fatigue fracture surfaces as a consequence of facet for-

mation and out of plane crack trajectories. An expected

large increase in closure due to a very large increase in

surface roughness for the 80 pm underaged material was

not observed due to the reversibility of the Mode II dis-

placement for this microstructure.

4. In vacuum the 80 pm grain size underaged alloy ex-

hibited highly irregular crack profiles and fatigue crack

growth rates up to 100 times slower than the 18/xm

underaged and 80/xm overaged materials. This high

degree of surface irregularity is attributed to the

coarse grain size and planar slip characteristics of the

underaged alloy.

5. The much greater fatigue crack growth resistance in

vacuum of the 80/xm underaged alloy is considered to be

a consequence of a number of factors including crack

branching, mixed Mode I and II crack advance, en-

hanced slip reversibility, and possibly welding of the

fracture surfaces on the unloading part of fatigue cycle.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was sponsored by the Air Force Office

of Scientific Research, United States Air Force Systems

Command, under Grant AFOSR-83-0061, Dr. Alan H.

Rosenstein, program manager. We would like to thank

Dr. S. Suresh for fumishing us with a copy of his paper on

crack deflection prior to publication.

REFERENCES

1. J.E. Shigley: Mechanical Engineering Design, 1977, McGraw-Hill,

New York, NY, p. 179.

2. R.A. Smith: in Fatigue Thresholds, Fundamentals and Engineering

Applications, J. Biicklund, A. F. Blom, and C. J. Beevers, eds., Engi-

neering Materials Advisory Services, Ltd., West Midlands, UK, 1981,

vol. I, p. 33.

3. P. Stenvall: in Fatigue Thresholds, Fundamentals and Engineering

Applications, J. Biicklund, A. F. Blom, and C. J. Beevers, eds., Engi-

neering Materials Advisory Services, Ltd., West Midlands, UK, 1981,

vol. II, p. 931.

4. W. Elber: Eng. Fracture Mech., 1970, vol. 2, p. 37.

5. T.C. Lindley and C.E. Richards: Mat. Sci. Eng., 1974, vol. 14,

p. 381.

6. R.O. Ritchie, S. Suresh, and C. M. Moss: J. Eng. Mat. and Tech.,

Trans. ASME Series H, 1979, vol. 102, p. 293.

7. N. Walker and C.J. Beevers: Fat. of Eng. Mat. and Struct., 1979,

vol. 1, p. 135.

8. R.O. Ritchie and S. Suresh: Metall. Trans. A, 1978, vol. 9A, p. 291.

9. J. Lindigkeit, G. Terlinde, A. Gysler, and G. LiJtjering: Acta Metall.,

1979, vol. 27, p. 1717.

10. Fu-Shiong Lin and E. A. Starke, Jr.: Mat. Sci. Eng., 1980, vol. 43,

p. 65.

11. Fu-Shiong Lin and E. A. Starke, Jr.: Mat. Sci. Eng., 1980, vol. 45,

p. 153.

12. Fu-Shiong Lin and E.A. Starke, Jr.: in Hydrogen in Metals, A.W.

Thompson and I. M. Bernstein, eds., TMS-AIME, Warrendale, PA,

1981, p. 485.

13. John A. Wert, N.E. Paton, C.H. Hamilton, and M.W. Mahoney:

Metall. Trans. A, 1981, vol. 12A, p. 1267.

14. Edgar A. Starke, Jr.: Strength of Metals and Alloys (ICSMAG), R. C.

Gifkins, ed., Pergamon Press, Oxford, 1983, vol. 3, p. 1025.

15. J. Petit, B. Bouchet, C. Goss, and J. de Fouguet: Fracture, Proc. 4th

Int. Conf. on Fracture (ICF4), D. M. R. Taplin, ed., University of

Waterloo Press, Waterloo, Canada, 1977, vol. 2, p. 867.

16. M.D. Holliday and C. J. Beevers: Int. J. of Fracture, 1979, vol. 15,

p. R27.

17. A.K. Vasudrvan and S. Suresh: Metall. Trans. A, 1982, vol. 13A,

p. 2271.

18. B.R. Kirby and C. J. Beevers: Fatigue of Eng. Mat. and Structures,

1979, vol. 1, p. 203.

19. S. Suresh: Metall. Trans. A, 1983, vol. 14A, p. 2375.

METALLURGICAL TRANSACTIONS A VOLUME 15A, MARCH 1984--563