15

Mater. Res. Soc. Symp. Proc. Vol. 1292 © 2011 Materials Research Society

DOI: 10.1557/opl.2011.18

Coupling of Defect Fields to Domains and Phase Transition Characteristics of Ferroelectric

Thin Films with Charged Defects

Ibrahim B. Misirlioglu

1

, Hale N. Cologlu

1

and Mehmet Yildiz

1

1

Faculty of Engineering and Natural Sciences, Sabanci University, Tuzla/Orhanli, 34956

Istanbul, Turkey

ABSTRACT

We analyze the effect of charged defects on the electrical domains, phase transition

characteristics and electrical properties of ferroelectric thin films with thin dead layers using a

non-linear thermodynamic model. Depending on their density and field strength, defects can pin

and couple to electrical domains in the film. For ultrathin films, depolarizing effects dominate

and the transition from the paraelectric state is into the multidomain ferroelectric state during

cooling and is strongly smeared. The competition between defect induced extrinsic effects and

the dead layer related limit is demonstrated.

INTRODUCTION

Phenomena related to inhomogeneities and defects in ferroelectric thin films have been an

interest for the scientific community since more than the last two decades. The impact of defect

fields on the physical properties of ferroelectric films have been the focus of numerous studies

including dedicated book chapters [1-10]. The motivation is to understand the structure-electrical

property relation in these materials that are strong candidates for several electronic applications.

Recently, with the emergence of techniques capable of fabricating very thin films, wherein

the distances through which defect fields permeate become comparable to film thickness, related

effects have gained a special importance. Defects with charges near the surfaces have also been

treated as centers strongly influencing switching characteristics or hinder domain wall motion [9,

18, 19].

An example to the macroscopic effect of a network of defects is the discussions on whether

the disappearance of ferroelectricity in ultrathin films is an intrinsic behavior set by atomistic

mechanisms or caused by interfacial inhomogeneities that put an extrinsic limit on the film

thickness. However, how such an intrinsic limit trend would be modified in the presence of even

a low density of charged defects remains a very interesting question.

In this article, we study the behavior of ferroelectric thin films with charged defects that are

introduced into the system as point potentials, sandwiched between metallic electrodes with dead

layers. To probe the strength of the defect effects we use the Landau-Ginzburg-Devonshire

(LGD) formalism for ferroelectric materials coupled with the interface conditions and defect

fields. Following the simulation of P at 25϶C, we study the phase transition characteristics of the

films both for the chosen thicknesses.

16

THEORY

As the first step, we first construct a two dimensional grid with a sandwich type capacitor

geometry that is 200n x kn cells where k (200) is the number of cells along the film thickness

(width) and each cell, n, has a dimension of 0.4 nm, imitating the unit cell dimensions of PZT.

The LGD volumetric free energy for an epitaxial single domain (001) ferroelectric film on a

(001) cubic substrate can be written as:

[]

dVFwFFFFFwF

V

DLESGEPT

³

−+−+++= )1()(

0

(1)

where w becomes zero in the dead layer and is one in the ferroelectric film. F

0

is the energy of

the paraelectric state and

2

3

2

2

2

1123

2

2

2

1

42

3

2

1

4

2

2

3

2

2

4

1112

6

3

6

2

6

1111

2

3

2

2

2

3

2

1

2

2

2

112

4

3

4

2

4

111

2

3

2

2

2

11

)]()()([)(

)()()(

PPP

PPPPPPPPPPPP

PPPPPPPPPPPPF

z

P

α

αα

ααα

+

+++++++++

++++++++=

(2)

is the energy due to the polarization P

i

(i=1,2,3) in the ferroelectric state.

α

i

,

α

ij

, and

α

ijk

are the

dielectric stiffness coefficients [20]. F

E

is the internal elastic energy both due to the misfit

between the film and the substrate as well as the self-strain given by:

()( )

00

2

1

klklijijijklE

CF

εεεε

−−=

(3)

where C

ijkl

is the elastic stiffness for a cubic crystal, İ

11

=İ

22

is the film-substrate misfit strain in

the pseudocubic limit, İ϶

ij

is the self-strain energy due to the paraelectric-ferroelectric phase

transition in the pseudocubic film. The gradient energy due to variations in P

i

is given by:

2

2

21

2

2

23

2

1

11

2

1

13

2

3

31

2

3

33

¸

¹

·

¨

©

§

+

¸

¹

·

¨

©

§

+

¸

¹

·

¨

©

§

+

¸

¹

·

¨

©

§

+

¸

¹

·

¨

©

§

+

¸

¹

·

¨

©

§

=

dx

dP

G

dz

dP

G

dx

dP

G

dz

dP

G

dx

dP

G

dz

dP

GF

G

(4)

where G

ij

are the gradient energy coefficients and we shall assume that it is isotropic for

convenience, namely G. We also neglect the variations along P

2

along y in the 2D limit. F

ES

is

the electrostatic energy of the system,

iiES

PEF −= where

i

E is found from the Maxwell

equation 0=

i

divD and

i

D are the dielectric displacement components. F

DL

is the energy of the

dead layer that is assumed to be a linear dielectric. Equation (1) is minimized and the

corresponding Euler-Lagrange equations are obtained from where we find the P components in

the system. The dead layer, when present, is assumed to be a high-k dielectric whose dielectric

constant is chosen as 20 with thicknesses as either one or two unit cells when specified.

The boundary conditions we employed for P

3,1

are dP

3

/dz=0 and dP

1

/dx=0 at the top and

bottom electrode-film interface of the ferroelectric layer. The periodic boundary conditions used

along the sides (x-axis) are;

),()0,(

33

LxzPxzP ===

,

),()0,(

11

LxzPxzP ===

(5)

Dirichlet boundary conditions are applied at the dead layer-electrode interface to solve the

fields coupled with P

1,3

. The equations of state are solved simultaneously employing a Gauss-

Seidel iterative scheme subject to boundary conditions mentioned above. We limit ourselves to

5000 iterations converging to a difference of 10

-8

between consecutive iterative P solution steps

when ferroelectricity exists.

17

The paraelectric-ferroelectric phase transition (PT) characteristics are studied through

finding P

3

by varying temperature between RT and 900ºC. These simulations are run for films

that are 6.4 and 14.4 nm thick in the presence and absence of charged defects. At each

temperature, the equations given above are solved for all P components and the resulting

configuration constitued the initial condition for the next step. The thickness of the dead layers in

these runs are also specified when necessary to demonstrate the competition between defect

effects and the dead layer effects. For convenience, we neglect the thermal expansion differences

and fix the value of the pseudocubic misfit in the entire range to solely reveal the PT

characteristics.

The material system considered in this study is heteroepitaxial (001) PZT 30/70 on a (001)

SrTiO

3

(ST) substrate with pseudomorphic top and bottom metallic electrodes. The values of the

dielectric stiffness coefficients and other thermodynamic parameters entering the calculations are

cited from [21]. Simulation results are presented for PZT 30/70 films of 6.4 nm and 14.4 nm.

DISCUSSION

Room temperature domain structures

We start by discussing the stable domain structures of the films at 25ºC for various film

thicknesses with and without defects in the light of our results. The electrodes lie on the

horizontal x-axis while perpendicular axis is denoted as z-axis.

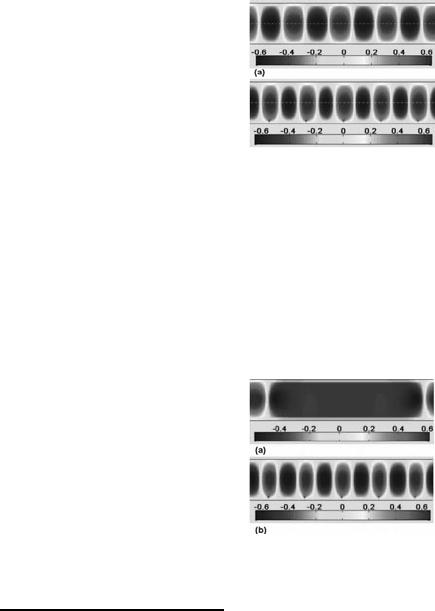

In Figure 1a-b, the color maps of the P

3

at 25ºC for 6.4 nm film are given in the presence

and absence of defects. In the 6.4 nm films, the 180º domains form regardless of the defects. We

obtain the domain period for the defect-free film as 13.33 nm whereas this is 16 nm for the

defected film which is due to the enhancement of P

3

in the vicinity of the defects in which the

order of distances that this enhancement takes place is comparable to the film thickness, favoring

a positive P

3

with the rest of the film coupling to these fields via the electrodes.

The results for the effect of defects on the stability of 180º domains in the 6.4 nm film under

bias are given in Figure 1c-d. A voltage of -0.2 V is applied to the bottom electrode while the

upper electrode is kept at 0 V. In the presence of the bias, there is no change in the defect free

film as it sustains the domain structure with a slightly higher number of switched cells in favor of

the bias field. When defects are present, P

3

in their vicinity is enhanced and this conversely

impacts the number of sites switched. As seen in Figure 1d, there is a significant portion that

have not switched but the behavior is still comparable to that of the defect-free 6.4 nm film. On

the other hand, the domain period, in both films remains nearly constant under -0.2 V bias. An

applied field opposing the sign of the defect induced field has to have values higher than those

for a defect-free film to induce complete switching.

Figure 1. The 25°C domain configurations of the 6.4 nm thick film with dead layers for (a)

defect-free film, (b) the film with charged defects near the bottom electrode, (c) defect-free film

under -0.2V bias (d) film with defects under -0.2V bias. Throughout the figures, scales are given

to display the range of P

3

in C/m

2

.

18

In Figure 2a-b we provide the results for the 14.4 nm films with two unitcell thick dead

layers. The domains are stable in both defected and defect-free cases at zero bias. The domain

period for the defect free film is interestingly larger than that of the defected film, where the

former has 20 nm periods and the latter has 16 nm. This is just the opposite of the 6.4 nm case.

Considering the magnitude of the jump at the ferroelectric-dead layer interface that determines

the amount of partially compensated bound charges, defects lead to an overall enhancement of P

3

in the film accompanied by a growing density of bound charges at the film-dead layer interface,

with a smaller period multidomain sequence to minimize the depolarizing fields. So, the 14.4 nm

film is under the influence of an enhanced depolarizing field due to the bias induced by defects

instead of a strong thickness effect mostly pronounced in ultrathin films.

Figure 2. The 25°C domain configurations of the 14.4 nm thick film with dead layer dielectric

constant İ=20 for (a) defect-free film, (b) the film with charged defects near the bottom

electrode.

In the 14.4 nm thick film, upon applying a -0.2 V bias to the bottom electrode, the defect-

free film has switched (Fig. 3a), while electrical domains persist in the defected one (Fig. 3b).

There is a near-single domain state under -0.2 V bias in the defect-free 14.4 nm film while the

film with defects has strongly pinned domains, both due to defect fields, sustaining the

multidomain configuration owing to the enhancement of P

3

in the domains through the long-

range effects, and the commensurately larger depolarizing field as well. It is critical here to

notice that the local depolarizing field magnitude will change with variations in the P

3

throughout the film while the defect fields are fixed.

Figure 3. The domains in the 14.4 nm film under -0.2V bias for (a) defect-free film and (b) film

with defects.

Phase transition characteristics

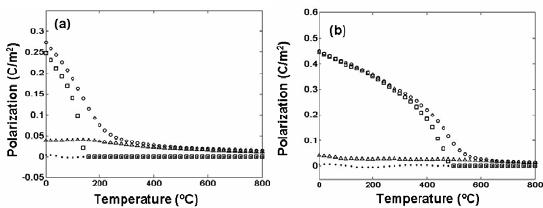

Before we go onto discussing the competition between the intrinsic-extrinsic limit effects,

we computed the P-T curve for perfect 6.4 nm and 14.4 nm films with no dead layers as

reference. The P solutions and T

C

of the two cases is the same and is around 880ºC, near twice

19

the bulk T

C

due to the compressive in-plane misfit and are not shown here for brevity. When

present, dead layers at both electrode-film interfaces are assumed to exist at a thickness of one

unit cell as already mentioned in the 6.4 nm film. We choose so as dead layers that are two unit-

cell thick reduce the T

C

of 6.4 nm film dramatically, to about 80ºC, confining the transition to a

small T region with respect to thicker films. During the simulations, if the transition from the

paraelectric state is into a multidomain ferroelectric state, one can track <|P

3

|> to allow the

detection of the transition point. Figure 4a shows the net P

3

and <|P

3

|> in the 6.4 nm thick film

without and with defects respectively. The transition temperature for the defect free film is

around 150ºC. The film with charged interface defects have a strongly smeared transition in the

150-300ºC range with a non-zero P

3

remaining and gradually leveling off at elevated

temperatures (See |P

3

| and <P

3

> for the defect free film in Figure 4a). The depolarizing field,

when dead layers are present, is quite strong for the 6.4 nm film due to the bound charge induced

potential drop at shorter distances when electrodes are kept at zero potential. Therefore, T

C

is

lowered significantly in the defect-free 6.4 nm film. A multidomain structure with the majority

of the volume having a positive P

3

in favor of the defect fields is stable at low temperatures

(Please see the <P

3

> for the defected films in Figure 4a). One must remember that these films are

also under the influence of a size limit via the depolarizing field taking effect in the presence of

dead layers.

Figure 4. P-T curves for (a) the defect-free and defected 6.4 nm thick film and (b) defect-free

and defected 14.4 nm thick film. Squares: <|P

3

|> for defect-free film, open circles: <|P

3

|> for

defected film, solid small circles: <P

3

> for defect-free film, triangles: <P

3

> for defected film in

both (a) and (b).

From Figure 4b, the paraelectric-ferroelectric transition temperature for the defect-free 14.4

nm film with 2 unit-cell thick dead layers is around 500ºC and into a multidomain state during

cooling. Throughout the whole temperature range, there is a non-zero, positive P

3

when defects

are present that implies the presence of a built-in P

3

. Similar results have been recently obtained

for thick (200 nm) single domain PZT 30/70 that does not have any dead layers but high

densities of continuous space charge distribution near one of the electrodes [21]. A stronger

smearing in the 6.4 nm film is resulting from the fact that the defect fields are much stronger due

to the film thickness, causing steeper potential drops that induce larger electric fields.

CONCLUSIONS

We have demonstrated the competition between the defect induced electrostatic fields with

the depolarizing fields due to dead layers is most prominent in the ultrathin films. Frozen-in

20

defect fields could strongly pin the domains in ultrathin films by electrostatic means, reducing

the switchable P

3

. The 14.4 nm film turns out to have potentially more stable P

3

and it seems that

the thicker films the less likely they will be under the influence of charged defects. During near-

equilibrium cooling, the paraelectric-ferroelectric transition is more prominently smeared in

ultrathin films compared to thicker ones even in the presence of widely seperated charged defect

sites. Still, the depolarizing effects should be expected to compete with defect fields in ultrathin

films in the presence of charged sites as demonstrated. It is obvious that charged defects, when

high in density, can significantly alter the properties but the depolarizing fields also develop

accordingly, dictating the electrical response as well as the domain configuration for films with

dead layers much thicker than a unit cell.

REFERENCES

1. S. Triebwasser, Phys. Rev. 118, 100 (1960).

2. A. P. Levanyuk and A. S. Sigov, “Defects and Structural Phase Transitions”, Volume 6,

in Ferroelectricity and Related Phenomena, edited by W. Taylor, Gordon and Breach

Science Publishers, (1988).

3. W. L. Warren, D. Dimos, G. E. Pike, B. A. Tuttle, M. V. Raymond, R. Ramesh and J. T.

Evans, Appl. Phys. Lett. 67, 866 (1995).

4. T. M. Shaw, S. Troiler-McKinstry, P. C, Mcintyre, Ann. Rev. Mat. Sci. 30, 263 (2000).

5. R. Ramesh, S. Aggarwal and O. Auciello, Mat. Sci. Eng. Rep. 32, 191 (2001).

6. C. S. Ganpule, A. L. Roytburd, V. Nagarajan, B. K. Hill, S. B. Ogale, E. D. Williams, R.

Ramesh and J. F. Scott, Phys. Rev. B 65, 014101 (2002).

7. H. Z. Jin and J. Zhu, J. Appl. Phys. 92, 4594 (2002).

8. M.-W. Chu, I. Szafraniak, R. Scholz, C. Harnagea, D. Hesse, M. Alexe and U. Gösele,

Nat. Mater. 3, 87 (2004).

9. X. Ren, Nat. Mater. 3, 91 (2004).

10. (9.5) E. Cockayne and B. P. Burton, Phys. Rev. B, 69, 144116 (2004).

11. D. Balzar, P. A. Ramakrishnan and A. M. Hermann, Phys. Rev. B 70, 092103 (2004).

12. S. P. Alpay, I. B. Misirlioglu, V. Nagarajan, R. Ramesh, Appl. Phys. Lett. 85, 2044

(2004).

13. Y. Xiao, V. B. Shenoy and K. Bhattacharya, Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 247603 (2005).

14. W. Laguta , A. M. Slipenyuk, I. P. Bykov, M. D. Glinchuk, M. Maglione, D. Michau, J.

Rosa, and L. Jastrabik, Appl. Phys. Lett. 87, 022903 (2005).

15. Y. Zheng, B. Wang and C. H. Woo, Appl. Phys. Lett. 88, 092903 (2006).

16. I. B. Misirlioglu, Mark Aindow, S. P. Alpay, and V. Nagarajan, Appl. Phys. Lett. 88,

102906 (2006).

17. Y. L. Li, S. Y. Hu, S. Choudhury, M. I. Baskes, A. Saxena, T. Lookman, Q. X. Jia, D. G.

Schlom and L. Q. Chen, J. Appl. Phys. 104, 104110 (2008).

18. S. V. Kalinin, S. Jesse, B. J. Rodriguez, Y. H. Chu, R. Ramesh, E. A. Eliseev and A. N.

Morozovska, Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 155703 (2008).

19. D. Schrade, B.X. Xu, R.Muller and D. Gross, Proc. Appl. Math. Mech. 7, 4040015

(2007).

20. M. J. Haun, Z. Q. Zhuang, E. Furman, S. J. Jang, L. E. Cross, Ferroelectrics 99, 45

(1989).

21. I. B. Misirlioglu, M. B. Okatan and S. P. Alpay, J. Appl. Phys.108, 034105 (2010).