Cazan

etal. Acta Vet Scand (2020) 62:42

https://doi.org/10.1186/s13028-020-00540-4

BRIEF COMMUNICATION

Detection ofLeishmania infantum DNA

andantibodies againstAnaplasma spp., Borrelia

burgdorferi s.l. andEhrlichia canis inadog

kennel inSouth-Central Romania

Cristina Daniela Cazan

1*

, Angela Monica Ionică

1,2

, Ioana Adriana Matei

1,3

, Gianluca D’Amico

1

, Clara Muñoz

4

,

Eduardo Berriatua

4

and Mirabela Oana Dumitrache

1

Abstract

Canine vector-borne diseases are caused by pathogens transmitted by arthropods including ticks, mosquitoes and

sand flies. Many canine vector-borne diseases are of zoonotic importance. This study aimed to assess the prevalence

of vector-borne infections caused by Dirofilaria immitis, Ehrlichia canis, Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato, Anaplasma spp.

and Leishmania infantum in a dog kennel in Argeș County, Romania. Dog kennels are shelters for stray dogs with no

officially registered owners that are gathered to be neutered and/or boarded for national/international adoptions by

various public or private organizations. The international dog adoptions might represent a risk in the transmission of

pathogens into new regions. In this context, a total number of 149 blood samples and 149 conjunctival swabs from

asymptomatic kennel dogs were assessed using serology and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction. Anti-

bodies against B. burgdorferi s.l. were detected in one dog (0.6%), anti-Anaplasma antibodies were found in five dogs

(3.3%), while ten dogs (6.7%) tested positive for D. immitis antigen. Overall, 20.1% (30/149) of dogs were positive for L.

infantum DNA. All samples were seronegative for anti-Leishmania antibodies. When adopting dogs from this region

of Romania, owners should be aware of possible infection with especially L. infantum. The travel of infected dogs may

introduce the infection to areas where leishmaniasis is not present.

Keywords: Canine vector-borne diseases, Dogs, Epidemiology, Kennel, Leishmania infantum

© The Author(s) 2020. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing,

adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and

the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material

in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material

is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the

permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creat iveco

mmons .org/licen ses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creat iveco mmons .org/publi cdoma in/

zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Findings

Canine vector-borne diseases (CVBDs) are currently

an emerging problem due to the zoonotic character of

some pathogens, for which dogs can serve as sentinels

of human infection [1]. CVBDs are mainly caused by

various species of bacteria and parasites, transmitted to

dogs by arthropod vectors, especially ticks, mosquitoes

or sand flies [2]. Among some of the major CVBD agents

that can infect dogs are the nematode Dirofilaria immi

-

tis, bacteria such as Ehrlichia canis, Borrelia burgdorferi

sensu lato, Anaplasma phagocytophilum, and the proto

-

zoan Leishmania infantum [3]. Evidence of northward

and eastward expansion of L. infantum in non-endemic

areas of Europe has been recorded, including in Roma

-

nia [4]. In 2014, after 80 years with no data, a case of

canine leishmaniasis (CanL) was described in Romania,

raising the need for updates on the disease in the coun

-

try [5]. In 2016, the first study to evaluate the prevalence

of CanL in Romania by sensitive polymerase chain reac

-

tion (PCR) and serology revealed a 3.7% seropositivity

and 8.7% PCR-positivity in the tested dogs (n = 80) [6].

Open Access

Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica

*Correspondence: [email protected]o

1

Department of Parasitology and Parasitic Diseases, University

of Agricultural Sciences and Veterinary Medicine of Cluj-Napoca, Calea

Mănăștur 3-5, 400372 Cluj-Napoca, Romania

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article

Page 2 of 4

Cazanetal. Acta Vet Scand (2020) 62:42

In 2019, similar findings were reported. From two inves-

tigated dog kennels located in two different counties in

South-Eastern Romania (Galaţi and Călăraşi), a CanL

seroprevalence of 8.3% was present in Galaţi County

(n = 60), while all samples from Călăraşi County (n = 50)

were negative. e overall seroprevalence of the study

was 4.54% (n = 110) [7]. Dog kennels are shelters for stray

dogs with no officially registered owners that are gathered

to be neutered and/or boarded for national/international

adoptions by various public or private organizations.

Co-infections with CVBD agents are common in kennel

dogs, mostly because dogs are easily exposed to more

than one vector species and the same vector species (par

-

ticularly in case of ticks) may be infected with more than

one pathogen [8]. Furthermore, apparently healthy dogs

are of particular epidemiological importance, as they can

act as reservoirs for human diseases [9].

e present study aimed to extend the current epidemio

-

logical knowledge on CVBDs in Romania in the context of

national/international dog adoptions which might represent

a risk in the transmission of pathogens into new regions.

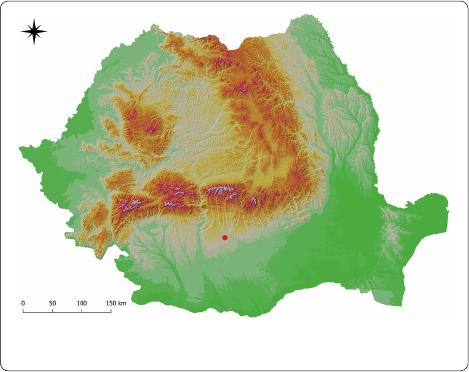

e study was performed during June–September

2017. Blood and conjunctival swab samples were col

-

lected from dogs (n = 149) located in a single kennel in

Argeş County (44.825N, 24.800 E) (Fig.1), a geographi

-

cal region that neighbors an area with recent local CanL

reports [5, 6]. Prior to sampling, the dogs were examined

for clinical signs of CanL, including lymphadenopathy,

dermatitis, hair loss, cachexia and hepato-splenomegaly.

e origin of the kennel dogs, prior of their gathering in

the kennel, was known as local, free roaming dogs.

e occurrence of Anaplasma spp., Borrelia burgdor

-

feri s.l., E. canis and D. immitis was assessed by using a

serological rapid test, SNAP

®

4Dx

®

(IDEXX Laboratories

Inc., Westbrook, ME, USA) according to the manufactur

-

er’s instructions.

Also, all serum samples were tested for the presence of

anti-L. infantum antibodies by using a rapid test (SNAP

®

Leishmania, IDEXX Laboratories Inc.) followed by the

use of a commercial kit (INGEZIM LEISHMANIA

15.LSH.K1, Ingenasa, Spain) according to the manufac

-

turer’s instructions.

Genomic DNA was isolated from both blood clots and

swabs using a commercial kit (Isolate II Genomic DNA

Kit, Bioline, London, UK) according to the manufac

-

turer’s instructions. Prior to DNA isolation, the swabs

were suspended in 300 µL 1× phosphate-buffered saline

(PBS). All DNA samples were processed by quantita

-

tive real-time PCR (qPCR) amplification of the kineto-

plast minicircle DNA of L. infantum, using the LEISH-1/

LEISH-2 primer pair and TaqMan-MGB probe according

to [10]. For the qPCR reaction, a positive control contain

-

ing genomic target DNA and a negative control without

DNA were included in order to assess the specificity of

the reaction and the presence of cross-contamination.

Statistical analysis was performed using EpiInfo

™

7 soft-

ware (https ://www.cdc.gov/epiin fo/index .html, Centers

for Disease Control and Prevention, USA). e frequency

and prevalence of infection and their 95% confidence

intervals were calculated. e differences among sex and

age groups were assessed by Chi-square testing (α = 0.05)

and correlations were evaluated by Spearman’s Rho.

No clinical signs of CanL or other diseases were

observed.

e results of the SNAP

®

4Dx

®

revealed antibod-

ies against B. burgdorferi s.l. in one dog (0.6%; 95% CI

0.02–3.68%), anti-Anaplasma antibodies in five dogs

(3.3%; 95% CI 1.10–7.66%), while ten dogs (6.7%; 95% CI

3.27–12.00%) tested positive for adult D. immitis female

antigens. All samples (n = 149) tested negative for anti-

L. infantum antibodies to both SNAP

®

Leishmania and

INGEZIM Leishmania.

e qPCR screening revealed that 30 dogs (20.1%; 95%

CI 14.02–27.48%) were positive for L. infantum DNA;

14 were positive on blood samples (9.4%; 95% CI 5.23–

15.26%) and 17 were positive on conjunctival swab samples

(11.4%; 95% CI 6.79–17.64%), with one animal expressing

positive results for both the blood and swab sample.

e differences in prevalence among sex were not sta

-

tistically significant (Table1). Although a higher preva-

lence was noted in dogs older than 8 years of age as

compared to younger dogs, the difference was not signifi

-

cant (Table1).

Among the Leishmania-positive dogs, three were also

harboring a D. immitis infection. However, there was

no significant correlation between the two pathogens

(R = 0.066; P = 0.423).

Many studies on the prevalence of CVBDs worldwide

have compared prevalence among asymptomatic and ill

Fig. 1 The sampling location in Argeş County, Romania (44.825 N,

24.800 E)

Page 3 of 4

Cazanetal. Acta Vet Scand (2020) 62:42

dogs, confirming the similar importance of both catego-

ries in the CVBDs transmission [9, 11–17]. Even though

the importance of ill dogs in CVBDs transmission is

more obvious, due to the presence of clinical signs, the

asymptomatic dogs could be infected for months or even

years, and still serve as reservoirs of pathogens to other

hosts including humans [9].

In Romania, several studies targeting the occurrence of

CVBPs in hosts and vectors have revealed a wide distri

-

bution, but with variable prevalence, according to various

local ecological factors. In a molecular survey, B. burg

-

dorferi s.l. was present in 1.4% of questing Ixodes ricinus

ticks, with an average local prevalence ranging between

0.7 and 18.8% in all major regions of Romania [18]. In

another study, Borrelia spp. DNA was identified in 138

of 534 (25.8%) questing I. ricinus ticks in eastern Roma

-

nia [19]. e present study revealed antibodies against B.

burgdorferi s.l. in only one dog (0.6%), but a low preva

-

lence in canine hosts (6/1146; 0.5%) was also previously

described in Romania [20].

Canine granulocytic anaplasmosis (CGA) is caused by

A. phagocytophilum, the bacteria being transmitted by I.

ricinus in Europe and infecting a wide range of domestic

and wildlife hosts, including humans [21]. CGA has been

reported in dogs from most regions of Romania, with an

overall seroprevalence of 2.1% [20]. e overall preva

-

lence of the infection in questing I. ricinus ticks was of

3.4%, with local prevalence values ranging between 0.2

and 22.4% [22].

In the present study no anti-E. canis antibodies were

detected. Canine monocytic ehrlichiosis caused by E.

canis is a disease transmitted by Rhipicephalus sanguineus

s.l. ticks [20]. In Romania, an overall prevalence of E. canis

of 2.1% (24/1146) was described in R. sanguineus s.l. ticks

[20]. Seropositivity to E. canis is considered a risk factor

for D. immitis and L. infantum infections [9].

e southern and southeastern areas of Romania are

endemic for dirofilariasis caused by D. immitis, the dog

heart worm [23]. Several studies have been conducted in

order to evaluate the prevalence of heart worm infection.

In a study evaluating 390 dogs from five regions of Roma

-

nia, a 6.9% PCR positivity, and a 7.1% seropositivity were

described [23].

Although other studies performed in Romania revealed

seroprevalences against L. infantum, varying between

3.7 and 8.3% [6, 7], all samples in the present study were

seronegative. However, L. infantum DNA was detected,

in 20.1% (30/149) of the tested dogs and in 9.4% of the

blood samples and 11.4% of the swab samples. Similar

findings were described by Solano-Gallego et al. [11]

when investigating dogs from Mallorca, Spain, where

37% of the sampled asymptomatic animals were PCR

positive for the skin samples and/or conjunctival swabs,

but seronegative. e PCR-positive and seronegative

dogs are considered clinically healthy and should be

retested in 6 to 12 months to assess the possible pro

-

gression of the infection towards disease [24]. e L.

infantum infection triggers a humoral response after

the incubation time, which in general can vary between

3weeks and 5months. us, the detection of L. infantum

DNA without seroconversion is a common finding [11].

Undoubtedly, the finding of antibodies against L. infan

-

tum indicates exposure to the parasite, but it is not clear

if these dogs are immune or if they will develop the dis

-

ease at some point. In the present study, the retesting of

the seronegative and PCR-positive clinically healthy dogs

was not possible, and further studies are needed in order

to have a better understanding of this category of dogs.

e prevalence of CVBD infections in dog kennels

is generally higher than the prevalence in the general

dog population in a certain area. is is because stray

dogs are much more exposed to pathogens before they

are gathered and kept at a high population density in

the kennels [25]. erefore, the dog kennels may act as

important sources of zoonotic diseases of veterinary and

public health interest.

In the actual European context of international adop

-

tions of kennel dogs, there is a permanent risk for spread

of pathogens and zoonotic transmission. A detailed

knowledge of the risk zones in Europe as a potential ori

-

gin for stray dogs is important in the prevention of this

potentially neglected category of source of infection rep

-

resented by the apparently healthy kennel dogs.

e study revealed a high prevalence of L. infantum

which appears to be widespread in Argeş County, Roma

-

nia. Further studies are imperative to actively search for

the sand fly vectors of CanL in the nearby areas, as well

as to evaluate the potential neglected role of the asymp

-

tomatic dogs in the reemergence of CVBDs in Romania.

Abbreviations

CVBDs: Canine vector-borne diseases; CanL: Canine leishmaniasis; s.l.: sensu

lato; CGA : Canine granulocytic anaplasmosis; PBS: Phosphate-buffered saline;

PCR: Polymerase chain reaction.

Table 1 The statistical analysis of PCR-positive samples

according tosex andage ofthesampled dogs (n = 149)

Frequency Prevalence (%) 95% CI P

Sex

Male 18/89 20.2 12.45–30.07 1

(Χ

2

= 1; d.f. = 1)

Female 12/60 20 10.78–32.33

Age (years)

≤ 3 9/47 19.1 9.15–33.26

0.061

(Χ

2

= 5.586;

d.f. = 2)

3–8 7/57 12.2 5.08–23.68

≥ 8 14/45 31.1 18.17–46.65

Page 4 of 4

Cazanetal. Acta Vet Scand (2020) 62:42

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the kennel personnel for all their help during

the study.

Authors’ contributions

MOD and AMI designed the study. CDC, IAM and GD participated in the field-

work. CDC, CM, EB, AMI and MOD serologically and molecularly identified the

pathogen species. AMI and MOD performed the data analysis. CDC drafted

the original manuscript. AMI, IAM, CM, EB, GD and MOD critically revised the

manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved

the final manuscript.

Funding

MOD was the grant recipient of CNCS-UEFISCDI Grant Agency Romania,

research grants PD38/2018 and TE299/2015. The work of MOD was supported

by the research grants PD38/2018 and TE299/2015. The work of CDC, AMI, IAM

and GD was supported by the research grant TE 299/2015. The publication

was supported by funds from the National Research Development Projects to

finance excellence (PFE)-37/2018–2020 granted by the Romanian Ministry of

Research and Innovation.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published

article.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author details

1

Department of Parasitology and Parasitic Diseases, University of Agricul-

tural Sciences and Veterinary Medicine of Cluj-Napoca, Calea Mănăștur 3-5,

400372 Cluj-Napoca, Romania.

2

CDS-9, “Regele Mihai I al Romaniei” Life

Science Institute, University of Agricultural Sciences and Veterinary Medicine

of Cluj-Napoca, Calea Mănăștur 3-5, 400372 Cluj-Napoca, Romania.

3

Depart-

ment of Microbiology, Immunology and Epidemiology, University of Agri-

cultural Sciences and Veterinary Medicine of Cluj-Napoca, Calea Mănăștur

3-5, 400372 Cluj-Napoca, Romania.

4

Department of Animal Health, Faculty

of Veterinary Science, Regional Campus of International Excellence ‘Campus

Mare Nostrum’, University of Murcia, 30100 Murcia, Spain.

Received: 31 March 2020 Accepted: 28 July 2020

References

1. Day MJ. One health: the importance of companion animal vector-borne

diseases. Parasites Vectors. 2011;4:49.

2. Otranto O, Dantas-Torres F, Breitschwerdt EB. Managing canine vectorborne

diseases of zoonotic concern: part one. Trends Parasitol. 2009;25:157–63.

3. Day MJ. The immunopathology of canine vector-borne diseases. Parasites

Vectors. 2011;4:48.

4. Mihalca AD, Cazan CD, Sulesco T, Dumitrache MO. A historical review on

vector distribution and epidemiology of human and animal leishmanioses

in Eastern Europe. Res Vet Sci. 2019;123:185–91.

5. Mircean V, Dumitrache MO, Mircean M, Bolfa P, Györke A, Mihalca AD.

Autochthonous canine leishmaniasis in Romania: neglected or (re)emerg-

ing? Parasites Vectors. 2014;7:135.

6. Dumitrache MO, Nachum-Biala Y, Gilad M, Mircean V, Cazan CD, Mihalca

AD, et al. The quest for canine leishmaniasis in Romania: the presence of an

autochthonous focus with subclinical infections in an area where disease

occurred. Parasites Vectors. 2016;9:297.

7. Cîmpan AA, Diakou A, Papadopoulos E, Miron LD. Serological study of

exposure to Leishmania in dogs living in shelters, in South-East Romania.

Rev Rom Med Vet. 2019;29:54–8.

8. Sauda F, Malandrucco L, Macrì G, Scarpulla M, de Liberato C, Terracciano G,

et al. Leishmania infantum, Dirofilaria spp. and other endoparasite infections

in kennel dogs in Central Italy. Parasite. 2018;25:2.

9. Cardoso L, Mendão C, Madeira de Carvalho L. Prevalence of Dirofilaria

immitis, Ehrlichia canis, Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato, Anaplasma spp. and

Leishmania infantum in apparently healthy and CVBD-suspect dogs in

Portugal-a national serological study. Parasites Vectors. 2012;5:62.

10. Francino O, Altet L, Sanchez-Robert E, Rodriguez A, Solano-Gallego L,

Alberola J, et al. Advantages of real-time PCR assay for diagnosis and moni-

toring of canine leishmaniosis. Vet Parasitol. 2006;137:214–21.

11. Solano-Gallego L, Miró G, Koutinas A, Cardoso L, Pennisi MG, Ferrer L, et al.

LeishVet guidelines for the practical management of canine leishmaniosis.

Parasites Vectors. 2011;4:86.

12. Aoun O, Mary C, Roqueplo C, Marié JL, Terrier O, Levieuge A, et al. Canine

leishmaniasis in south-east of France: screening of Leishmania infantum

antibodies (western blotting, ELISA) and parasitaemia levels by PCR quantifi-

cation. Vet Parasitol. 2009;166:27–31.

13. Moshfe A, Mohebali M, Edrissian G, Zarei Z, Akhoundi B, Kazemi B, et al.

Canine visceral leishmaniasis: asymptomatic infected dogs as a source of L.

infantum infection. Acta Trop. 2009;112:101–5.

14. Cabezón O, Millán J, Gomis M, Dubey JP, Ferroglio E, Almeria S. Kennel

dogs as sentinels of Leishmania infantum, Toxoplasma gondii, and Neospora

caninum in Majorca Island, Spain. Parasitol Res. 2010;107:1505–8.

15. Wang JY, Ha Y, Gao CH, Wang Y, Yang YT, Chen HT. The prevalence of canine

Leishmania infantum infection in western China detected by PCR and

serological tests. Parasites Vectors. 2011;4:69.

16. Fakhar M, Motazedian MH, Asgari Q, Kalantari M. Asymptomatic domestic

dogs are carriers of Leishmania infantum: possible reservoirs host for human

visceral leishmaniasis in southern Iran. Comp Clin Pathol. 2012;21:801–7.

17. Pantchev N, Schnyder M, Vrhovec MG, Schaper R, Tsachev I. Current surveys

of the seroprevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi, Ehrlichia canis, Anaplasma phago-

cytophilum, Leishmania infantum, Babesia canis, Angiostrongylus vasorum and

Dirofilaria immitis in dogs in Bulgaria. Parasitol Res. 2015;114:117–30.

18. Kalmár Z, Mihalca AD, Dumitrache MO, Gherman CM, Magdaş C, Mircean

V, et al. Geographical distribution and prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi

genospecies in questing Ixodes ricinus from Romania: a countrywide study.

Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2013;4:403–8.

19. Răileanu C, Moutailler S, Pavel I, Porea D, Mihalca AD, Savuta G, et al. Borrelia

diversity and co-infection with other tick borne pathogens in ticks. Front

Cell Infect Microbiol. 2017;7:36.

20. Mircean V, Dumitrache MO, Györke A, Pantchev N, Jodies R, Mihalca AD,

et al. Seroprevalence and geographic distribution of Dirofilaria immitis and

tick borne infections (Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Borrelia burgdorferi

sensu lato, and Ehrlichia canis) in dogs from Romania. Vector Borne Zoonotic

Dis. 2012;12:595–604.

21. Egyed L, Élő P, Sréter-Lancz Z, Széll Z, Balogh Z, Sréter T. Seasonal activity and

tick-borne pathogen infection rates of Ixodes ricinus ticks in Hungary. Ticks

Tick Borne Dis. 2012;3:90–4.

22. Matei IA, Kalmár Z, Magdaș C, Magdaș V, Toriay H, Dumitrache MO, et al.

Anaplasma phagocytophilum in questing Ixodes ricinus ticks from Romania.

Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2014;6:408–13.

23. Ionică AM, Matei IA, Mircean V, Dumitrache MO, D’Amico G, Győrke A,

et al. Current surveys on the prevalence and distribution of Dirofilaria

spp. and Acanthocheilonema reconditum infections in dogs in Romania.

Parasitol Res. 2015;114:975–82.

24. Solano-Gallego L, Morell P, Arboix M, Alberola J, Ferrer L. Prevalence of Leishma-

nia infantum infection in dogs living in an area of canine leishmaniasis endemic-

ity using PCR on several tissues and serology. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:560–3.

25. Simonato G, Frangipane di Regalbono A, Cassini R, Traversa D, Beraldo P, Tes-

sarin C, et al. Copromicroscopic and molecular investigations on intestinal

parasites in kenneled dogs. Parasitol Res. 2015;114:1963–70.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in pub-

lished maps and institutional affiliations.