Fatigue Properties of Nitrided Ultrafine Ferrite-Cementite Steels

under Rotating Bending Fatigue Testing

Y. FURUYA, H. HIRUKAWA, S. MATSUOKA, S. TORIZUKA, and H. KUWAHARA

Fatigue tests under rotating bending were conducted on nitrided ultrafine ferrite-cementite

steels. The ultrafine ferrite-cementite steels included carbon-increased and phosphorus-added

versions to investiga te the effects of grain growth suppression during nitriding. In the carbon-

increased versions, grain growth was successfully suppressed both in the nitrided layer and in the

core region. On the other hand, the low-carbon versions showed grain growth in the core region,

even in the phosphoru s-added types, althoug h grain growth was suppresse d in the nitrided layer.

In the fatigue tests, many of the nitrided specimens revealed fish-eye fractures originating from

inclusions located in or beneath the nitrided layer. In spite of the occurrence of fish-eye frac-

tures, the fatigue strength of the carbon-increased versions was markedly impr oved due to

nitriding, whereas it was a little improved in the low-carbon versions. The fatigue strength of the

nitrided specimens was closely related to hardness at the fracture origin, even when fish-eye

fractures occurred. This was why nitriding markedly improved the fatigue strength of the car-

bon-increased versions in which grain growth was success fully suppressed and high ha rdness

was maintained beneath the nitrided layer.

DOI: 10.1007/s11661-008-9544-z

The Minerals, Metals & Materials Society and ASM International 2008

I. INTRODUCTION

GRAIN refinement is a logical way of strengthening

steel, because this process achieves high strength without

concomitantly increasing the ductile-to-brittle transition

temperature. Using the latest techniques, grain sizes can

be refined to below 1 lm. More specifically, several

research studies have succeeded in grain refinement that

yields submicron ferrite grains, starting from bulk

steel.

[1–3]

Our institute has also established a submicron

grain-refinement process using multipass warm caliber

rolling.

[4,5]

This process yields ultrafine-grained steel

bars that are thick and long enough to machine into

specimens for mechanical tests. The microstructure of

this ultrafine-grained steel is not ferrite-pearlite but

ferrite-cementite, so this ultrafine-grained steel is termed

ultrafine ferrite-cementite steel in this report.

Although many kinds of mechanical properties are

required of structural materials, fatigue strength is one

of the most important, because it is a frequently

required characteristic of mechanical components. This

has prompted research into fatigue strength in ultrafine

ferrite-cementite steel.

[6–8]

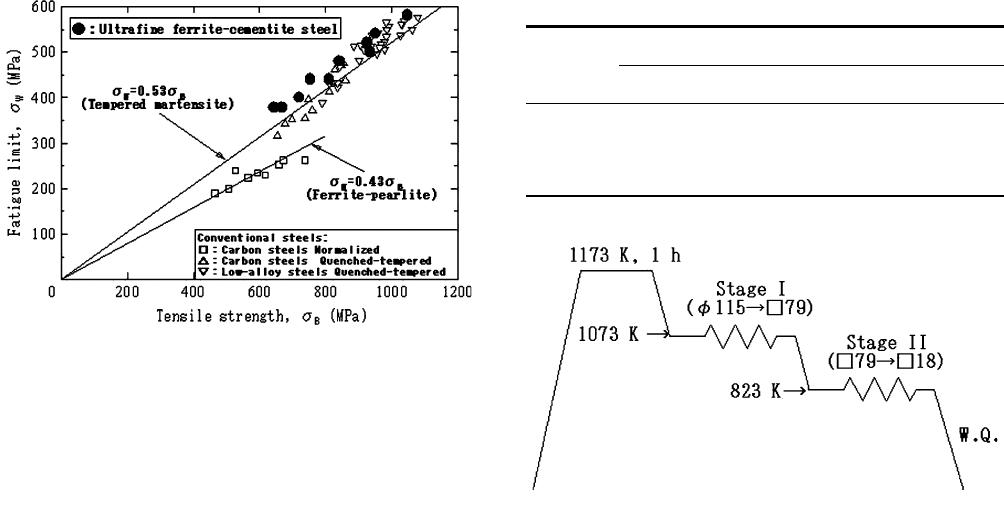

Previous studies have com-

pared ultrafine ferrite-cementite steel with conventional

tempered martensite and ferrite-pearlite steels.

[9,10]

Although tempe red martensite steel showed higher

fatigue strength than ferrite-pearl ite steel, the fatigue

strength of ultrafine ferrite-cementite steel matched that

of tempered martensite, as seen in Figure 1. The reason

for this high degree of fatigue strength is that the

microstructure of ultrafine ferrite-cementite steel is not

only ultrafine but also uniform.

On the other hand, surface modification to harden the

surface is frequently conducted in steels destined for

machine structural use. Surface modification enhances

both fatigue strength and wear resistance. It is therefore

necessary to investigate the potential for surface mod-

ification of ultrafine ferrite-cementite steel. Typical

surface modification methods are carburizing, induction

hardening, and nitriding. Carburizing is, however, very

difficult to apply to ultrafine ferrite-cementite steel. In

this process , steels are held at high temperatures, above

1173 K, for a long time. At this temperature, transfor-

mation into austenite occurs, making it almost impos-

sible to preserve the ultrafine ferr ite grains. The

remaining choices were induction hardening or nitrid-

ing; for this study, we selected nitriding.

In nitriding, steels are held at temperatures ranging

from 773 to 873 K for a long time. In this temperature

range, grain growth of ferrite grains, but never trans-

formation, can take place. Suppression of grain growth

is thus the key to nitriding ultrafine ferrite-cementite

steel. In nitrided steels, fish-eye fractures frequently

occur, even beneath the nitrided layer,

[11,12]

so grain

growth needs to be suppressed in the core region as well

as in the nitrided layer. One effective way of suppressing

grain growth is to pin the grain boundaries. In our

previous research,

[8]

cementite particles revealed strong

Y. FURUYA and H. HIRUKAWA, Senior Researchers, and

S. TORIZUKA, Group Leader, are with the National Institute for

Materials Science, 1-2-1 Sengen, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305-0047, Japan.

formerly Deputy Director General, with the National Institute for

Materials Science, 1-2-1 Sengen, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305-0047, Japan, is

Professor, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Faculty of

Engineering, Kyushu University, 744 Motooka, Nishi-ku, Fukuoka

819-0395, Japan. H. KUWAHARA, Vice President, is with the

Research Institute for Applied Science, Tanaka Ohicho, Sakyo-ku,

Kyoto 606-8202, Japan.

Manuscript submitted December 27, 2007.

Article published online May 7, 2008

2068—VOLUME 39A, SEPTEMBER 2008 METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS A

pinning effects in ultrafine ferrite-cementite steel, sup-

pressing grain growth during annealing. In ultrafine

ferrite-cementite steel, raising the carbon content

resulted in increased numbers of cementite particles,

and the carbon-increased version showed negligible

grain growth even during 30-hour annealing at 773 K.

Moreover, in that study, phosphorus addition also

showed the effects of grain growth suppression while

annealing the ultrafine ferrite-cementite steel. This effect

was likely to be a type of solute drag.

[13,14]

In this study, fatigue strength was investigated in

nitrided ultrafine ferrite-cementite steel. The fatigue tests

were conducted under rotating bending. In general ,

surface-hardened steels are used under conditions where

high stress acts on and around the surface, so the

rotating bending fatigue testing is closer to actual use

than the axial loading fatigue testing. The effects of grain

growth suppression were investigated by conducting

fatigue tests on the carbon-increased and phosphorus-

added versions of the nitrided ultrafine ferrite-cementite

steels. The ultrafine ferrite-cementite steels used in this

study were the same as in our previous investigation.

[8]

II. EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURE

A. Preparation of Materials

Table I shows the chemical composition of the steels.

15C is a base steel containing about 0.15 pct (as mass

pct) carbon. 45C, containing about 0.45 pct carbon, is a

version made to investigate the effect of grain growth

suppression due to the presence of cementite particles

during nitriding. 15C-P steel, containing about 0.1 pct

phosphorus, was used to investigate the grain growth

suppressive effect of phosphorus addition. 45C-P steel, to

which both carbon and phosphorus had been added, was

a version designed to investigate their multiple effects.

Ingots of these steels were melted under vacuum on a

laboratory scale and forged into round bars 115 mm in

diameter. Submicron grain refinement was then con-

ducted using multipass warm caliber rolling.

[4]

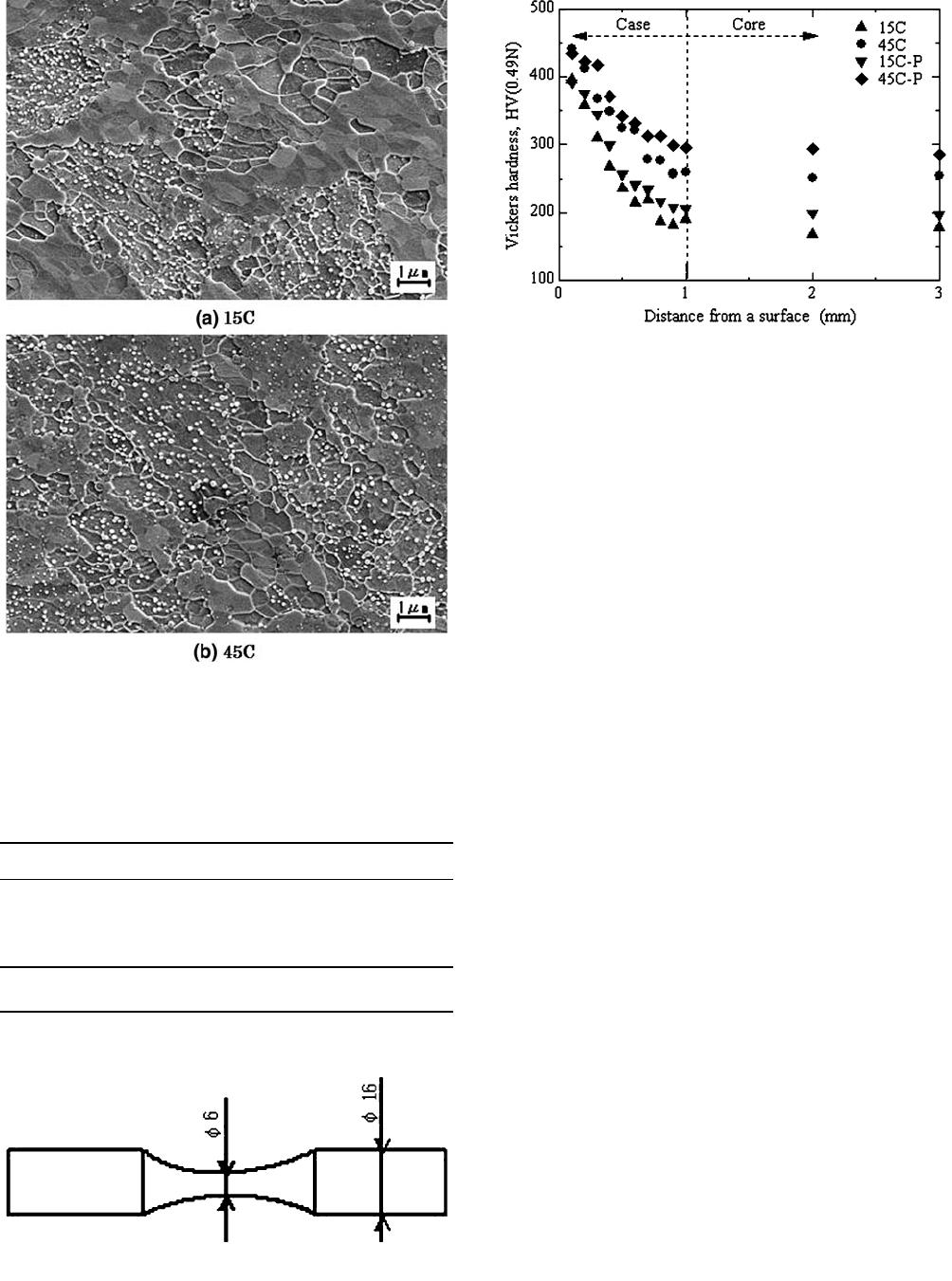

Figure 2

shows the submicron grain-refinement process. Stage I

comprised hot caliber rolling at 1073 K to form 79-mm-

square bars. Stage II, resulting in 18-mm-square bars,

comprised multipass warm caliber rolling to refine the

ferrite grains. The accumulated reduction of the cross-

sectional area in stage II was 95 pct, and the 18-mm-

square bars were water cooled immediately after the

warm caliber rolling.

Figure 3 shows the microstructure of the ultrafine

ferrite-cementite steels. Although only 15C and 45C are

shown, the microstructures of 15C-P and 45C-P are

similar to those of 15C and 45C, respectively. The 45C

carbon-increased version reveals dense cementite parti-

cles. Table II shows the mechanical properties and

nominal ferrite grain sizes of the ultrafine ferrite-

cementite steels. The tensile strengths range from 842

to 1048 MPa, and the ferr ite grain sizes are about

0.4 lm, regardless of version.

B. Fatigue Test Specimen and Nitriding Condition

Figure 4 shows a fatigue test specimen. The specimens

were hourglass shaped with a diameter of 6 mm at the

minimum section. After machining to this shape, plasma

nitriding

[15–17]

was conducted at 773 K for 16 hours,

followed by water cooling. After this plasma nitriding,

the narrowed section of the specimens was repolished,

removing 0.1 mm of the surface layer. As a result, the

diameter of the nitrided specimens was 5.8 mm at the

minimum section when the fatigue tests were conducted.

The surface of the minimum section was finally polished

in the axial direction with 600-grit paper.

C. Microstructure Observation and Mechanical Tests

The microstructures of the nitrided specimens were

observed using a field emission– scanning electron

Table I. Chemical Compositions of the Steels

Steel

Element (Mass Pct)

CSiMn P S

15C 0.14 0.31 1.51 0.001 0.0006

45C 0.43 0.31 1.50 <0.001 0.0009

15C-P 0.14 0.30 1.48 0.093 0.0007

45C-P 0.45 0.30 1.49 0.10 0.0011

Fig. 2—Schematic illustration of the caliber rolling process.

Fig. 1—Fatigue limits of the ultrafine ferrite-cementite steels

[8]

plot-

ted against tensile strength, together with conventional tempered

martensite and ferrite-pearlite steels.

METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS A VOLUME 39A, SEPTEMBER 2008—2069

microscope (FE-SEM). These observations were

conducted on the electropolished surfaces

[18]

of cross

sections. Nominal ferrite grain sizes were measured

using the FE-SEM images according to ASTM stan-

dards.

[19]

The mechanical tests conducted were Vickers hard-

ness and rotating bending fatigue tests. The Vickers

hardness was measured at 0.49 N on mirror-polished

surfaces of cross sections. The rotating bending fatigue

tests were conducted at 120 Hz up to 10

8

cycles. The

fatigue tests were conducted at room temperature in air.

The fracture surface after fatigue tests was observed

with FE-SEM, and in the case of fish-eye fractures, the

origin was analyzed by energy-dispersive atomic X-rays

(EDAX).

III. EXPERIMENTAL RESULTS

A. Hardness Distribution and Microstructure of Nitrided

Specimens

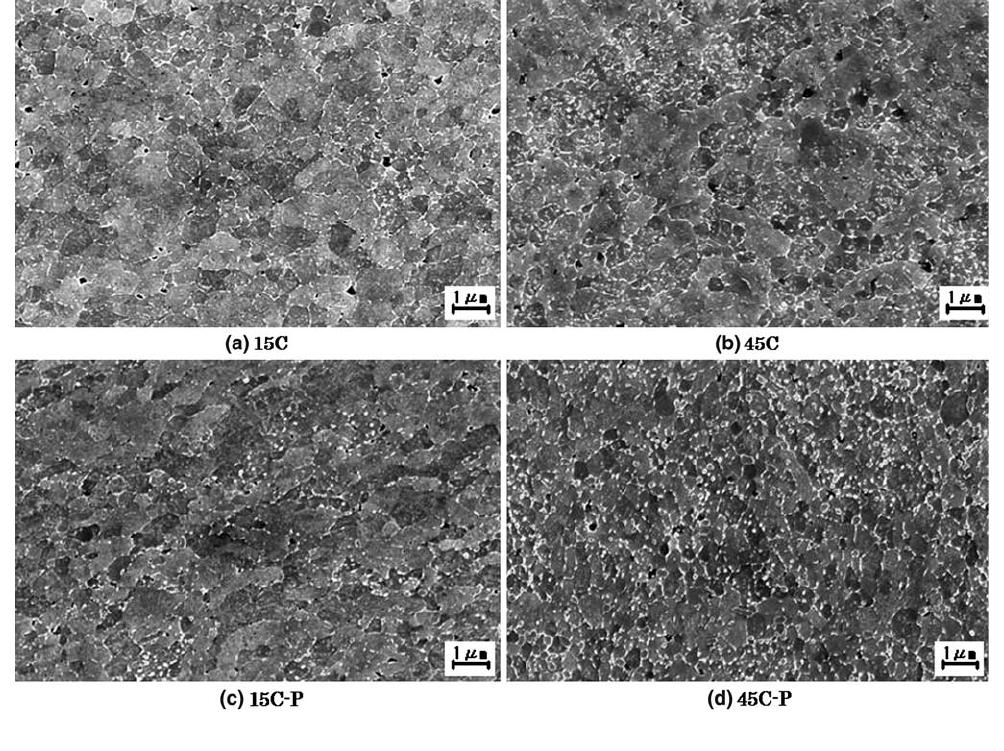

Figure 5 shows Vickers hardness distributions of the

nitride specimens. These hardness distributions were

measured in the grip section of the nitrided specimens,

whose surface had not been polished after the nitriding.

The hardness at 0.1 mm distance from the surface thus

corresponds to that at the surface of the narrowed

section, because the 0.1-mm surface layer of the nar-

rowed section was removed by polishing after nitriding.

The hardness at 3-mm distance from the surface

therefore corresponds to that at the center of the

narrowed section.

These hardness distributions revealed that the case

depth, i.e., the depth of the nitrided layer, was about

1 mm. No plateau region was observed, regardless of

the version of the ultrafine ferrite-cementite steel. The

hardness at the surface of the narrowed section ranged

from HV391 to HV441: a little higher in 45C and 45C-P

than in 15C and 15C-P. The difference in the hardness

was more marked in the core region, i.e., beneath the

Fig. 3—Microstructures of the ultrafine ferrite-cementite steels

before nitriding.

[8]

Table II. Mechanical Properties and Nominal Ferrite Grain

Sizes of the Ultrafine Ferrite-Cementite Steels before

Nitriding

[8]

Steel r

y

(MPa) r

B

(MPa) d (Pct) HV dn (lm)

15C 829 842 17 286 0.45

45C 920 952 17 300 0.43

15C-P 926 926 13 308 0.43

45C-P 1020 1048 15 339 0.44

r

y

: lower yield strength, r

B

: tensile strength, d: total elongation,

HV: Vickers hardness, and dn: nominal ferrite grain size.

Fig. 4—Profiles of a fatigue test specimen in millimeters.

Fig. 5—Vickers hardness distributions of nitrided specimens from

surface to center.

2070—VOLUME 39A, SEPTEMBER 2008 METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS A

nitrided layer. The hardness at the center ranged from

HV178 to HV286. When the hardn ess at the center was

compared with that before nitriding, the reduction of

hardness during nitriding was about HV110 in 15C and

15C-P, in contrast to about HV50 in 45C and 45C-P.

The decline in hardness in the core region was thus very

high in the 15C and 15C-P steels.

Figures 6 and 7 show microstructures of the nitrided

layer and the core region, respectively. These micro-

structures were also observed in the grip section of the

nitrided specimens. Figure 6 shows the microstructures

observed at 0.1 mm below each surface, so these

microstructures correspond to those at the surface of

the narrowed section. The microstructures in Figure 7,

observed at 3 mm below the surface, similarly corre-

spond to those at the center.

The ferrite grains in the nitrided layer remained

ultrafine regardless of the version of the ultrafine ferr ite-

cementite steel. Fine precipitates, which were not

observed before the nitriding, were observed around

the grain boundaries. These fine precipitates were

reduced in proportion to increasing distance from the

surface, and accordingly, ferrite grain sizes were

increased in 15C and 15C-P. Although these precipitates

were too fine to allow identification of their chemical

compositions by EDAX, they were assumed to be

nitrides.

The ferrite grains in the core region showed significant

growth in 15C and 15C-P, while grain growth was

negligible in 45C a nd 45C-P. The nominal ferrite grain

sizes in the core region were 4.4 lm in 15C, 0.7 lmin

45C, 2.6 lm in 15C-P, and 0.7 lm in 45C-P. In the

carbon-increased versions, thus, grain growth during

nitriding was successfully suppressed, and somewhat

suppressed in the phosphorus-added versi on.

B. Fatigue Test Results

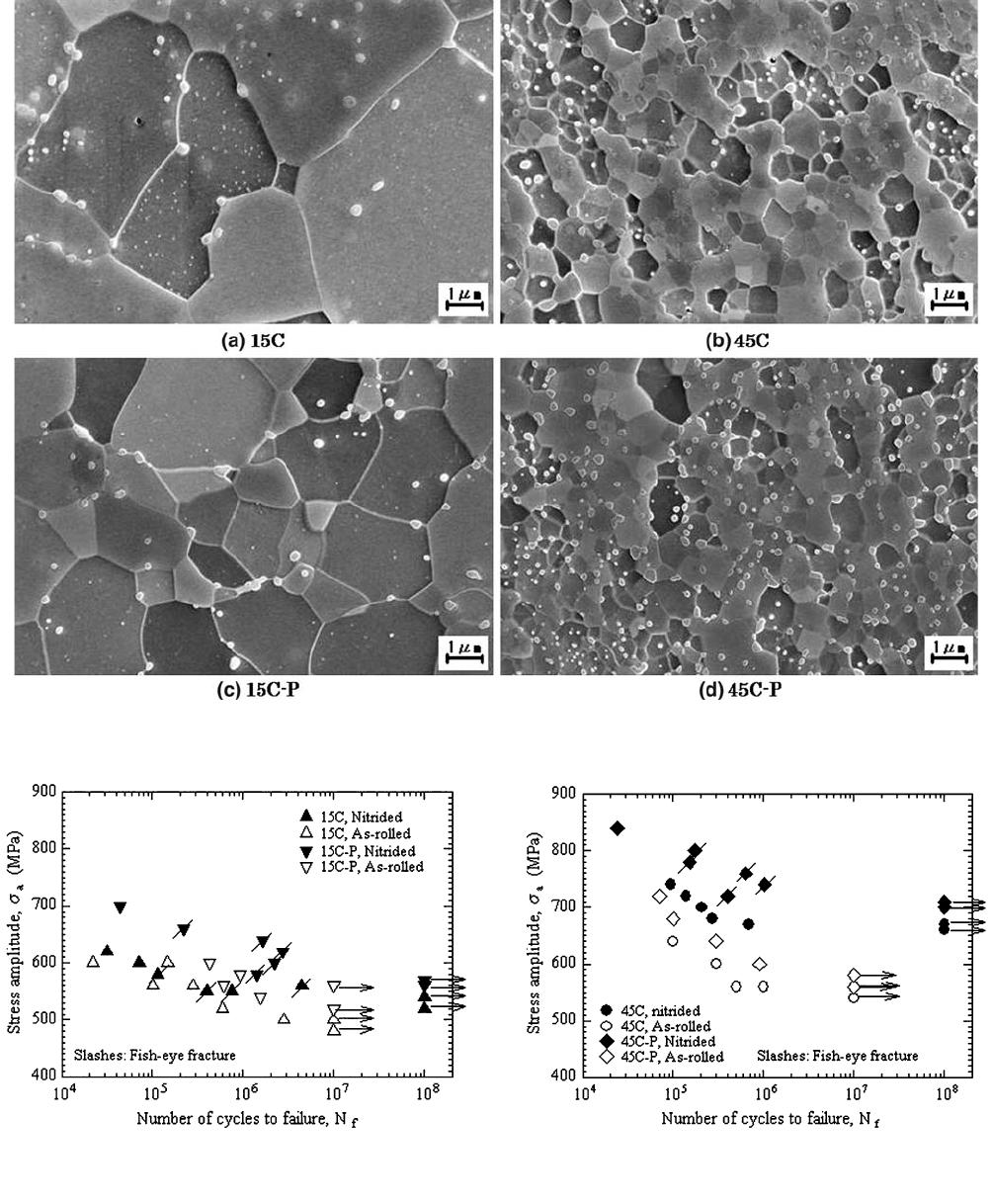

Figure 8 shows the fatigue test results of 15C and

15C-P, comparing the nitrided specimens with the

as-rolled specimens, i.e., specimens without nitriding. The

nitrided specimens showed fish-eye fractures that did not

occur in the as-rolled specimens. The fish-eye fracture

tended to occur at lower stress amplitudes and longer

fatigue lives. This trend was similar to a stepwise S-N

curve in gigacycle fatigue of high-strength steel.

[20]

The

fish-eye fracture origins were located in or beneath the

nitrided layer. The nitrided specimens revealed higher

fatigue strength at above 10

6

cycles than the as-rolled

specimens, while the degree of improvement was small.

Fig. 6—Microstructures of the nitrided layer, observed on the electropolished surfaces of a cross section using FE-SEM.

METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS A VOLUME 39A, SEPTEMBER 2008—2071

When the fatigue strength was compared between 15C

and 15C-P for the nitrided specimens, the 15C-P showed

slightly higher fatigue strength.

Figure 9 shows fatigue test results for the 45C and

45C-P nitrided specimens, together with the as-rolled

specimens. In 45C and 45C-P, only the 45C-P nitrided

specimens showed fish-eye fractures. The fish-eye

fracture origins were also located in or beneath the

nitrided layer. In both 45C and 45C-P, the nitrided

specimens revealed much higher fatigue strength than

Fig. 7—Microstructures of the core region, observed on the electropolished surface of a cross section using FE-SEM.

Fig. 8—Fatigue test results from the nitrided 15C and 15C-P speci-

mens, together with those for as-rolled specimens, i.e., specimens

without nitriding.

[8]

Fig. 9—Fatigue test results using the nitrided 45C and 45C-P

specimens, together with those using as-rolled specimens, i.e., non-

nitrided specimens.

[8]

2072—VOLUME 39A, SEPTEMBER 2008 METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS A

the as-rolled specimens. When the fatigue strength was

compared between the nitrided 45C and 45C-P speci-

mens, 45C-P showed clearly higher fatigue strength.

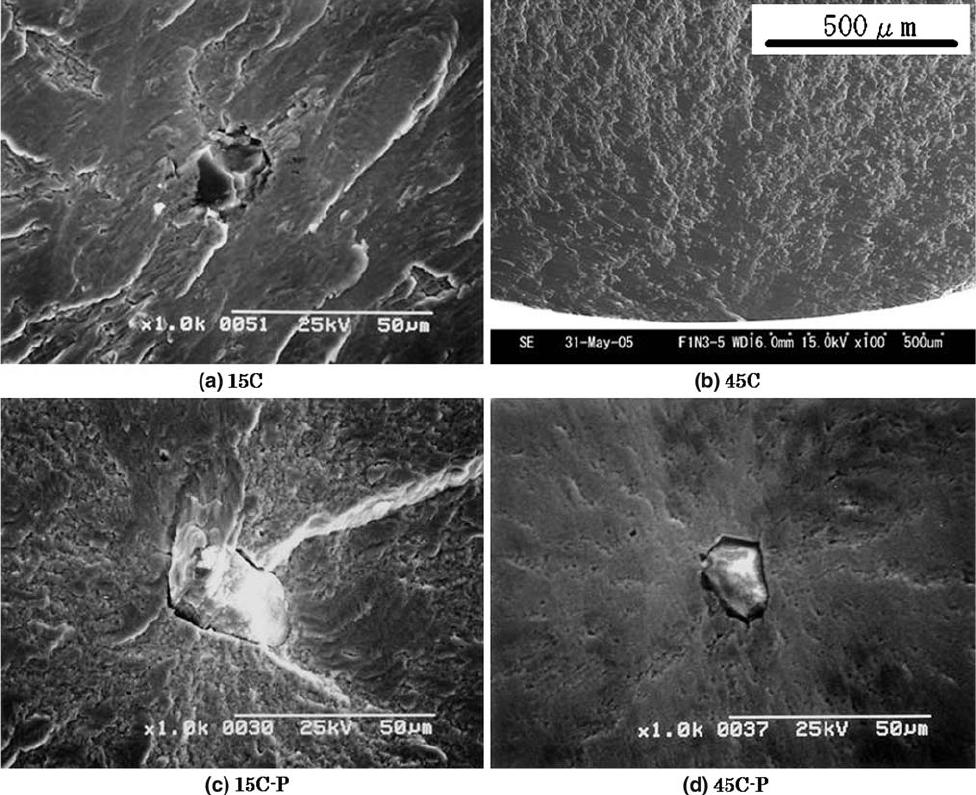

Figure 10 shows typical fracture surfaces of the

nitrided specimens. Most fish-eye fracture origins were

an Al

2

O

3

inclusion, as seen in Figures 10(a) through (d),

while in some fish-eye fracture surfaces, no inclusions

were identified at the origin. In 45C, only surface

fractures occurred, as seen in Figure 10(b). The Al

2

O

3

inclusion sizes ranged from 13 to 34 lm regardless of the

version of the ultrafine ferrite-cementite steel. Distances

from the surface to the fish-eye fracture origin ranged

from 0.35 to 1.05 mm.

IV. DISCUSSION

A. Nitriding of the Ultrafine Ferrite-Cementite Steel

One of the key points in nitriding ultrafine ferrite-

cementite steel is how to suppress grain growth during

the process. This suppression of grain growth should be

achieved both in the nitrided layer and in the core

region. In the nitrided layer, grain growth was negligi-

ble, regardless of the version of ultrafine ferrite-cement-

ite steel, as seen in Figure 6. In the nitride layer, fine

nitrides, precipitated during nitriding, reveal a pinning

effect on the grain boundaries at the same time. Thus,

grain growth during nitriding is automatically sup-

pressed in the nitrided layer. The key point here is

suppression of grain growth in the core region.

The ferrite grain sizes in the core region of the nitrided

specimens showed a marked difference between versions

of the ultrafine ferrite-cementite steels, as seen in

Figure 7. In 45C and 45C-P, the grain growth in the

core region was successfully suppressed, unlike in 15C

and 15C-P. This is due to the pinning effect of dense

cementite particles. Namely, the pinning effect of the

dense cementite particles is strong enough to suppress

grain growth during nitriding. A sufficiently strong

pinning effect is expected to appear in the other

precipitated particles, because the grain growth in the

Fig. 10—Typical FE-SEM fractographs of the nitrided specimens at around the fracture origin. (a) 15C broken at 1.2 · 10

5

cycles at 580 MPa,

(b) 45C broken at 4.9 · 10

5

cycles at 670 MPa, (c) 15C-P broken at 1.6 · 10

6

cycles at 640 MPa, and (d) 45C-P broken at 1.0 · 10

6

cycles at

740 MPa.

METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS A VOLUME 39A, SEPTEMBER 2008—2073

nitrided layer is similarly suppressed by fine nitrides. In

conclusion, this study demon strates that using the

pinning effect of precipitated particles effectively sup-

presses grain growth during nitriding.

Phosphorus addition also resulted in suppression of

the grain growth. The ferrite grain sizes in the core

region of the nitrided specimens were smaller in the

15C-P than in the 15C. This is due to a type of solute-

drag effect.

[13,14]

However, this effect, which is due to

0.1 pct phosphorus addition, is not strong enough to

sufficiently suppress grain growth during nitriding,

because the ferrite grain size in the core region of the

15C-P specimens was enlarged up to 2.6 lm. Conse-

quently, addition of phosphorus is not as effective as

using the pinning effect of precipitated particles to

suppress grain growth during nitriding.

On the other hand, the details of the fine nitrides

observed in the nitrided layer were not identified in this

study. Based on the chemical compositions in Table I,

elements able to form fine nitrides are Fe, Si, and Mn.

Of these elements, Fe can be excluded. Ferrous nitrides

are formed in an external nitriding layer, i.e.,a

composite layer, which is the outer region of the nitrided

layer that is normally a few tens of microns thick after

plasma nitriding.

[16,17]

However, 0.1 mm of the surface

layer was removed by polishing, so in this study, the

external nitriding layer was completely removed. More-

over, 0.3 pct Si is not able to increase the hardness in the

internal nitriding layer, i.e., the diffusion layer.

[21,22]

0.3 pct of Si is too little to increase Vickers hardness so

much as to be seen in Figure 5. Therefore, the fine

nitrides are the most likely to be manganese nitrides.

B. Fatigue Strength of the Nitrided Ultrafine

Ferrite-Cementite Steel

The fatigue test results of this study are summarized

in Table III. Improvements of the fatigue limit due to

nitriding are 120 MPa in 45C and 45C-P, while they are

from 40 to 60 MPa in 15C and 15C-P. The fatigue limits

of the nitrided specimens appear to be more closely

related to the Vickers hardness in the core region than

that at the surface. To investigate the effect of hardness,

more detailed analysis is necessary, because fish-eye

fractures occur in the nitrided specimens. If a fish-eye

fracture occurs under rotating bending, local stress

amplitudes at the fracture origin are smaller than the

nominal stress amplitude due to the stress gradie nt.

Moreover, the hardness of the nitrided specimens varies

from the surface to the core region. Therefore, relation-

ships between the local stress amplitude and the

hardness at the fracture origin must be taken into

account when investigating the effect of hardness.

Figure 11 shows a r

a

c

/HV

c

vs N

f

diagram for nitrided

and as-rolled specimens of 15C, 45C, 15C-P, and 45C-P.

In this diagram, the local stress amplitude, r

a

c

,is

normalized with Vickers hardness, HV

c

, at the fracture

origin. In this formulation, the results of the as-rolled

specimens show a unique curve, reducing the difference

between the versions of the ultrafine ferrite-cementite

steel. This means that the hardness of the matrix is a

major factor that controls the fatigue strength of

ultrafine ferrite-cementite steel. On the other hand, the

results for the nitrided specimens show large scattering,

even in this formulation. In the nitrided specimens, the

results that end in fish-eye fracture, which themselves

show large scattering, are distributed in a higher fatigue

strength region than those ending in surface fracture.

Based on Figure 11, the fatigue strength of the nitrided

ultrafine ferrite -cementite steel will be discussed subse-

quently.

Many of the results ending in fish-eye fracture show

good agreement with the results for the as-rolled

specimens, although a few of the results are distributed

in a somewhat higher fatigue strength region. This

suggests that an effect of hardness is large on fatigue

strength, even in case of fish-eye fractures occurring in

the nitrided specimens. In the case of surface fracture,

hardness of the matrix is a dominant factor in fatigue

strength, as mentioned previously. However, in the case

of fish-eye fracture, the dominant factor is the inclusion

size at the fracture origin, and past research on high-

strength steels whose tensile strength exceeded

1500 MPa suggested that the effect of hardness was

small.

[23–25]

In contrast, the present results suggest that

the hardness at the fracture origin is also a factor in the

case of fish-eye fracture of the nitrided ultrafine ferrite-

cementite steel. Therefore, to achieve high fatigue

strength in nitrided ultrafine ferrite-cementite steel,

maintaining high hardness beneath the nitrided layer is

Table III. Fatigue Limits and Vickers Hardness of the

Nitrided Specimens

Steel

Vickers Hardness* Fatigue Limit (MPa)

Surface Core As-Rolled Nitrided

15C 396 140 480 540

45C 441 243 540 660

15C-P 391 174 520 560

45C-P 435 283 580 700

*Vickers hardness of the nitrided specimens.

Fig. 11—r

a

c

/HV

c

vs N

f

diagram. Both r

a

c

and HV

c

indicate the local

stress amplitude and Vickers hardness at the fracture origin.

2074—VOLUME 39A, SEPTEMBER 2008 METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS A

necessary, as well as increasing the hardness in the

nitrided layer, because fish-eye fractures occur both in

and beneath the nitrided layer. Thus, the fatigue

strengths of 45C and 45C-P were distinctly improved

by nitriding; i.e., 45C and 45C-P successfully main-

tained high hardness beneath the nitrided layer,

because grain growth was suppressed during nitriding.

In contrast, it was not possible to suppress grain

growth in 15C and 15C-P, leading to loss of hardness

beneath the nitrided layer, so the improvement in

fatigue stren gth was small.

The results ending in surface fracture of the nitrided

specimens are distributed in a lower fatigue strength

region than those of the as-rolled specimens. This means

that, although the fatigue strength of the nitrided

specimens is improved by the increased hardness at the

surface, as seen in Figures 8 and 9, that improvement is

not entirely attributable to the hardness at the surface,

even in the case of surface fracture. One possible reason

for this is that the hardness distribut ions seen in

Figure 5 show no plateau region in the nitrided layer.

The hardness falls steeply with increasing depth below

the surface, so once initiated, a fatigue crack propagates

easily, resulting in a loss of fatigue strength. The other

possible reason is that the fatigue strength of the

nitrided layer itself is lower than that of the as-rolled

specimens. In terms of the effects of residual stress,

[11,12]

plasma-nitrided specimens might initially appear to

harbor compressive residual stress in an internal nitrided

layer. However, compressive residual stress improves

fatigue strength, so the trend of the results ending in

surface fracture would indicate the opposite to be the

case.

In summary, the most important finding of this

research is that suppressing grain growth is a necessary

condition for achieving high fatigue strength in nitrided

ultrafine ferrite-cementite steel. This grain growth must

be suppressed beneath, as well as in, the nitrided layer.

Using the pinn ing effect of precipitated particles is an

effective way of achieving this. On the other hand, for

greater improvement of fatigue strength, refinement of

inclusion sizes is a necessary process, because fish-eye

fractures originating from an inclusion occurred even

in the nitrided 45C-P specimens in which grain growth

had been successfully suppressed. An effective way to

avoid fish-eye fracture is to reduce the inclusion size

appearing at the fracture origin. The other item is

modification of the nitrided layer, which improves the

surface fracture properties. The surface fracture prop-

erty of the nitrided specimens is not as good as might

be expected from their surface hardness. This modifi-

cation of the nitrided layer would require an investi-

gation of appropriate alloying elements in addition to

Mn, in order to yield a plateau region of hardness in

the nitrided layer and thus improve the fatigue strength

of the nitrided layer itself.

V. CONCLUSIONS

Fatigue tests under rotating bending were conducted

for nitrided ultrafine ferrite-cementite steels. The ultrafine

ferrite-cementite steels included carbon-increased and

phosphorus-added versions to investigate the effects of

grain growth suppression during nitriding. The main

conclusions obtaine d in this study are as follows.

1. Ferrite grains near the surface of the nitrided layer

remained ultrafine, regardless of the version of the

ultrafine ferrite-cementite steel, due to the pinning

effect of fine nitrides precipitated during the nitrid-

ing process.

2. Although the ferrite grains in the core region were

enlarged in the low-carbon versions, grain growth

during nitriding was successfully suppressed in the

carbon-increased versions due to the pinning effect

of dense cementite particles. As a result of this sup-

pression of grain growth, hardness degradation in

the core region during the nitriding was smaller in

the carbon -increased versions than in the low-

carbon versions.

3. In the fatigue tests, many of the nitrided specimens

revealed fish-eye fractures originating from inclu-

sions located in or beneath the nitrided layer. In

spite of the occurrence of fish-eye fractures, the fati-

gue strength of the carbon-increased versions was

markedly improved by nitriding, but only slightly

improved in the low-carbon versions.

4. The fatigue strength of the nitrided specimens was

closely related to hardness at the fracture origin,

even though fish-eye fractures occurred. This was

why nitriding markedly improved the fatigue

strength of the carbon-increased versions in which

suppression of grain growth had been successful

and where high hardness had been maintained

beneath the nitrided layer.

5. These results indicate that suppression of grain

growth is a necessary condition, even in the core

region, to achieve high fatigue strength in nitrided

ultrafine ferrite-cementite steels, and to this end,

using the pinning effect of precipitated particles is

effective.

REFERENCES

1. N. Tsuji, Y. Saito, H. Utsunomiya, and S. Tanigawa: Scripta

Mater., 1999, vol. 40, pp. 795–800.

2. A. Azushima, K. Aoki, and T. Inoue: Tetsu-to-Hagane

´

, 2001,

vol. 87, pp. 762–766.

3. T. Hayashi, S. Torizuka, T. Mitsui, K. Tsuzaki, and K. Nagai:

CAMP-ISIJ, 1999, vol. 12, p. 385.

4. A. Ohmori, S. Torizuka, K. Nagai, N. Koseki, and Y. Kogo:

Tetsu-to-Hagane

´

, 2003, vol. 89, pp. 781–88.

5. S. Torizuka, E. Muramatsu, S.V.S. Narayana Murty, and

K. Nagai: Scripta Mater., 2006, vol. 55, pp. 751–54.

6. T. Sawai, S. Matsuoka, and K. Tsuzaki: Tetsu-to-Hagane

´

, 2003,

vol. 89, pp. 726–33.

7. Y. Furuya, S. Matsuoka, S. Shimakura, T. Hanamura, and

S. Torizuka: Scripta Mater., 2005, vol. 52, pp. 1163–67.

8. Y. Furuya, S. Matsuoka, S. Shimakura, T. Hanamura, and

S. Torizuka: Metall. Mater. Trans. A, 2007, vol. 38A, pp. 2984–91.

9. S. Nishijima, A. Ishii, K. Kanazawa, S. Matsuoka, and

C. Masuda: NRIM Fatigue Data Sheet Technical Document,

No. 5, National Research Institute for Metals, Tokyo, 1989.

10. S. Matsuoka, N. Nagashima, and S. Nishijima: NRIM Material

Strength Data Sheet Technical Document, No. 17, National

Research Institute for Metals, Tokyo, 1997.

METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS A VOLUME 39A, SEPTEMBER 2008—2075

11. P. De la Cruz, M. Ode

´

n, and T. Ericsson: Mater. Sci. Eng. A, 1998,

vol. 242, pp. 181–94.

12. K. Genel, M. Demirkol, and M. Capa: Mater. Sci. Eng. A, 2000,

vol. 279, pp. 207–16.

13. G.J. Shiflet and H.I. Aaronson: Metall. Trans. A, 1990, vol. 21A,

pp. 1413–32.

14. K.W. Liu and F. Mu

¨

cklich: Acta Mater., 2001, vol. 49, pp. 395–403.

15. B. Edenhofer: Heat Treat. Met., 1974, vol. 1, pp. 56–67.

16. H. Miyamura, J. Takada, H. Kuwahara, and S. Kikuchi: J. Mater.

Sci., 1986, vol. 21, pp. 2514–18.

17. J. Takada, Y. Ohizumi, H. Miyamura, H. Kuwahara, S. Kikuchi,

and I. Tamura: J. Mater. Sci., 1986, vol. 21, pp. 2493–96.

18. M. Hayakawa, T. Hara, S. Matsuoka, and K. Tsuzaki: J. Jpn.

Inst. Met., 2000, vol. 64, pp. 460–66.

19. ASTM E112: Annual Book of ASTM Standards, ASTM,

Philadelphia, PA, 1996.

20. S. Nishijima and K. Kanazawa: Fat. Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct.,

1999, vol. 22, pp. 601–07.

21. T. Takase, Y. Nakamura, M. Sumitomo, K. Kita, and H. Ono:

J. Jpn. Inst. Met., 1976, vol. 40, pp. 663–69.

22. T. Sasaki, T. Yamada, A. Kono, and M. Aoyagi: J. Jpn. Inst.

Met., 1977, vol. 41, pp. 381–85.

23. Y. Furuya and S. Matsuoka: Metall. Mater. Trans. A, 2002,

vol. 33A, pp. 3421–31.

24. Y. Furuya and S. Matsuoka: Trans. Jpn. Soc. Mech. Eng., 2004,

Ser. A, vol. 70–696, pp. 1058–65 (in Japanese).

25. Y. Furuya, H. Hirukawa, T. Kimura, and M. Hayaishi: Metall.

Mater. Trans. A, 2007, vol. 38A, pp. 1722–30.

2076—VOLUME 39A, SEPTEMBER 2008 METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS A