123

SPRINGER BRIEFS IN PHYSICS

Shinichiro Seki

Masahito Mochizuki

Skyrmions

in Magnetic

Materials

SpringerBriefs in Physics

Editorial Board

Egor Babaev, University of Massachusetts, USA

Malcolm Bremer, University of Bristol, UK

Xavier Calmet, University of Sussex, UK

Francesca Di Lodovico, Queen Mary University of London, UK

Maarten Hoogerland, University of Auckland, New Zealand

Eric Le Ru, Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand

Hans-Joachim Lewerenz, California Institute of Technology, USA

James Overduin, Towson University, USA

Vesselin Petkov, Concordia University, Canada

Charles H.-T. Wang, University of Aberdeen, UK

Andrew Whitaker, Queen’s University Belfast, UK

More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/8902

Shinichiro Seki • Masahito Mochizuki

Skyrmions in Magnetic

Materials

123

Shinichiro Seki

Center for Emergent Matter Science (CEMS)

RIKEN

Wako, Japan

Masahito Mochizuki

Department of Physics and Mathematics

Aoyama Gakuin University

Sagamihara, Japan

ISSN 2191-5423 ISSN 2191-5431 (electronic)

SpringerBriefs in Physics

ISBN 978-3-319-24649-9 ISBN 978-3-319-24651-2 (eBook)

DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-24651-2

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015953776

Springer Cham Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London

© Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2016

This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of

the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation,

broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information

storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology

now known or hereafter developed.

The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication

does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant

protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use.

The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book

are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or

the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any

errors or omissions that may have been made.

Printed on acid-free paper

Springer International Publishing AG Switzerland is part of Springer Science+Business Media (www.

springer.com)

Contents

1 Theoretical Model of Magnetic Skyrmions ................................ 1

1.1 What Is a Skyrmion?..................................................... 1

1.2 Stabilisation of Magnetic Skyrmions ................................... 2

1.3 Model and Phase Diagrams.............................................. 4

References ...................................................................... 12

2 Observation of Skyrmions in Magnetic Materials......................... 15

2.1 Skyrmions in Non-centrosymmetric Magnets .......................... 15

2.2 Skyrmions in Centrosymmetric Magnets ............................... 22

2.3 Skyrmions at Interface ................................................... 26

References ...................................................................... 30

3 Skyrmions and Electric Currents in Metallic Materials .................. 33

3.1 Emergent Electromagnetic Fields ....................................... 33

3.2 Electric-Current-Driven Motions of Skyrmions ........................ 35

3.3 Topological Hall Effect .................................................. 41

3.4 Manipulation by Electric Current ....................................... 44

Appendix 1: Landau-Lifshitz-Gilbert-Slonczewski Equation ................ 48

Appendix 2: Derivation of Thiele’s Equation ................................. 50

References ...................................................................... 56

4 Skyrmions and Electric Fields in Insulating Materials ................... 57

4.1 Magnetoelectric Skyrmions and Manipulation by Electric Fields ..... 57

4.2 Magnetoelectric Resonance of Skyrmions .............................. 62

References ...................................................................... 66

5 Summary and Perspective ................................................... 67

References ...................................................................... 69

v

Chapter 1

Theoretical Model of Magnetic Skyrmions

Abstract Skyrmions were originally proposed by Tony Skyrme in the 1960s to

account for the stability of hadrons in particle physics as a topological solution of

the non-linear sigma model. Bogdanov and his collaborators theoretically predicted

their realisation in chiral-lattice ferromagnets with finite Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya

interaction due to the lack of spatial inversion symmetry. In this chapter, an overview

of theoretical aspects of magnetic skyrmions is provided.

1.1 What Is a Skyrmion?

Keen competition among interactions in magnets often gives rise to non-collinear

or non-coplanar spin structures such as vortices, domain walls, bubbles and spirals.

These spin structures endow hosting materials with interesting physical properties

and useful device functions, which have attracted intense research interest from

viewpoints of fundamental science and technical applications. For example, domain

walls and vortices in metallic ferromagnets can be driven by spin-polarised electric

currents [1–3], and their application to magnetic storage devices such as race-track

memory is anticipated [4]. Magnetic spirals in insulating magnets often exhibit

rich magnetoelectric cross-correlation phenomena due to the coupling between

magnetism and electricity through the generation of ferroelectric polarisation via a

relativistic spin–orbit interaction [5–7]. In addition to these spin structures, magnetic

skyrmions, vortex-like swirling spin structures characterised by a quantised topo-

logical number, are attracting considerable research attention because it has turned

out that their peculiar response dynamics to external fields hold highly promising

properties with applications to spintronic device functions [8–10].

Skyrmions were originally proposed by Tony Skyrme in the 1960s to account for

the stability of hadrons as quantised topological defects in the three-dimensional

(3D) non-linear sigma model [11, 12]. They have now turned out to be highly

relevant to a spin structure in condensed-matter systems. A magnetic skyrmion

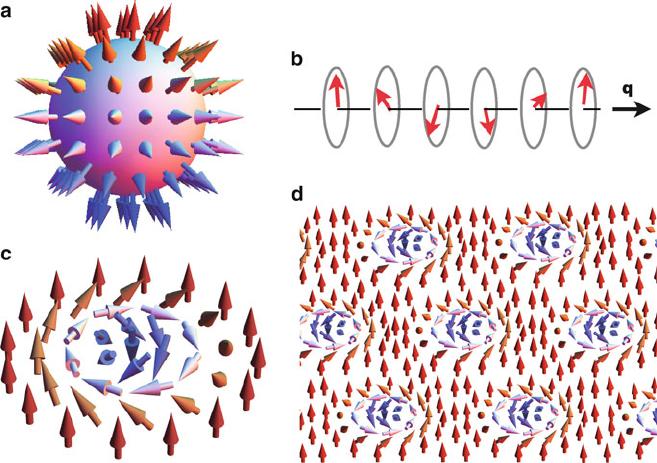

comprises spins pointing in all directions wrapping a sphere similar to a hedgehog,

as shown in Fig. 1.1a. The number of such wrappings corresponds to a topological

invariant, and thus, the skyrmion has topologically protected stability. It has been

found that skyrmions are indeed realised in quantum Hall ferromagnets [13, 14],

© Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2016

S. Seki, M. Mochizuki, Skyrmions in Magnetic Materials, SpringerBriefs

in Physics, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-24651-2_1

1

2 1 Theoretical Model of Magnetic Skyrmions

Fig. 1.1 (a) Schematic of the original hedgehog-type skyrmion proposed by Tony Skyrme in

the 1960s, whose magnetisations point in all directions wrapping a sphere. (b) Schematic of the

helical state realised in chiral-lattice magnets as a consequence of the competition between the

Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya and ferromagnetic exchange interactions. (c) Schematic of a skyrmion

recently discovered in chiral-lattice magnets, which corresponds to a projection of the hedgehog-

type skyrmion on a two-dimensional (2D) plane. Its magnetisations also point in all directions

wrapping a sphere. (d) Schematic of the skyrmion crystal realised in chiral-lattice magnets under

an external magnetic field in which skyrmions are hexagonally packed to form a triangular lattice

ferromagnetic monolayers [15], doped layered antiferromagnets [16], liquid crys-

tals [17] and Bose–Einstein condensates [18]. Recently, the realisation of magnetic

skyrmions in chiral-lattice magnets was theoretically predicted [19–21] and later

experimentally discovered [6, 22].

1.2 Stabilisation of Magnetic Skyrmions

There are several mechanisms for skyrmion formation in magnets. One major

mechanism is the competition between the Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya and ferromag-

netic exchange interactions [19–21]. In chiral-lattice ferromagnets without spatial

inversion symmetry, such as B20 compounds (MnSi, FeGe, Fe

1x

Co

x

Si) and copper

oxoselenite Cu

2

OSeO

3

, the Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya interaction, which originates

from the relativistic spin–orbit coupling, becomes finite [23, 24]. In a continuum

spin model, the Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya interaction is expressed by

1.2 Stabilisation of Magnetic Skyrmions 3

H

DM

/

Z

drM .r M/; (1.1)

where M is the classical magnetisation vector. This interaction alone favours a

rotating magnetisation alignment with a turn angle of 90

ı

and competes with

the ferromagnetic exchange interaction that favours a collinear ferromagnetic spin

alignment. As a result of their competition, a helical spin order with a uniform

turn angle shown in Fig. 1.1b is realised in the absence of an external magnetic

field [25–28]. On the application of a weak magnetic field, skyrmions appear as

vortex-like topological spin textures shown in Fig. 1.1c in a plane normal to the

field irrespective of field direction. In a skyrmion, magnetisations are parallel to

an applied magnetic field at its periphery but antiparallel at its centre. This spin

structure corresponds to a projection of the original hedgehog-type skyrmion on a

2D plane. The topological nature of this projected skyrmion is characterised by the

topological invariant

G D

Z

d

2

r

@

O

n

@x

@

O

n

@y

O

n; (1.2)

where

O

n D M=jMj is the unit vector pointing in the direction of magnetisation. This

quantity is a sum of solid angles spanned by three neighbouring magnetisations; for

a single skyrmion, its value is given by 4Q, with Q.D˙1/ being the skyrmion

number. The sign of Q corresponds to that of magnetisation at the skyrmion core,

i.e. Q DC1 (Q D1) for up (down) magnetisation at the core. Skyrmions

often form a hexagonal lattice, the so-called skyrmion crystal shown in Fig. 1.1d.

Magnetisations align ferromagnetically in a stacking direction to form rod-like

or tube-like structures. Typically, skyrmions in chiral-lattice ferromagnets are

3–100nm in size, which is determined by the ratio of the Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya

interaction D to the ferromagnetic exchange interaction J.

Another major mechanism of skyrmion formation is the competition between

magnetic dipole interaction and easy-axis anisotropy [29–32]. In thin-film spec-

imens of ferromagnets with perpendicular easy-axis anisotropy, the anisotropy

favours out-of-plane magnetisations, whereas a long-range magnetic dipole interac-

tion favours in-plane magnetisations. Their competition results in a periodic stripe

with spins rotating in a thin-film plane. An application of a magnetic field normal

to the thin-film plane turns the stripe into a periodic arrangement of magnetic

bubbles or skyrmions. Skyrmions or bubbles of this origin tend to be large, typically

3–100m in size, which is orders of magnitude larger than skyrmions in chiral-

lattice ferromagnets. In addition to these two mechanisms, frustrated exchange

interactions [33] and four-ring exchange interactions [15] have been theoretically

proposed as origins of skyrmion formation. Skyrmions of these origins tend to be

atomically small.

4 1 Theoretical Model of Magnetic Skyrmions

1.3 Model and Phase Diagrams

To describe the magnetism in MnSi as a prototypical chiral-lattice ferromagnet, the

continuum spin model that was proposed by Bak and Jensen in 1980 [34]isas

follows:

H D

Z

d

3

r

J

2a

.rM/

2

C

D

a

2

M .rM/

1

a

3

B M

C

A

1

a

3

.M

4

x

C M

4

y

C M

4

z

/

A

2

2a

Œ.r

x

M

x

/

2

C .r

y

M

y

/

2

C .r

z

M

z

/

2

: (1.3)

The first and second terms represent the ferromagnetic exchange interaction (J >0)

and the Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya interaction, respectively. The third term denotes the

Zeeman coupling to an external magnetic field B. The fourth and fifth terms are

magnetic anisotropies allowed by a cubic crystal symmetry, but they turn out to

play a minor role as far as realistically small values of A

1

and A

2

are considered.

Here, a is the lattice constant.

In Ref. [35], the stability of a skyrmion-crystal phase was theoretically studied

based on this model by writing the Ginzburg–Landau free energy functional near

T

c

as

FŒM D

Z

d

3

r

r

0

M

2

C J.rM/

2

C 2DM .rM/

CUM

4

B M

: (1.4)

When a uniform component of magnetisation M

uniform

is induced by a magnetic

field, we obtain the term

X

q

1

;q

2

;q

3

.M

uniform

m

q

1

/.m

q

2

m

q

3

/ı.q

1

C q

2

C q

3

/ (1.5)

from the quartic term in Eq. (1.4), where m

q

is the Fourier component of M.r/.

Wave vectors q

1

, q

2

and q

3

should have a fixed modulus determined by two

competing gradient terms, i.e. the ferromagnetic exchange term and Dzyaloshinskii–

Moriya term. In addition, the energy change should be proportional to M

uniform

On

by symmetry, where On is a vector normal to the plane spanned by the three wave

vectors. Therefore, one can gain energy from this term for the skyrmion-crystal