ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Effect of Mandibular Advancement Surgery on Tongue Length

and Height and Its Correlation with Upper Airway Dimensions

N. K. Sahoo

1

•

Shiv Shankar Agarwal

2

•

Sanjeev Datana

2

•

S. K. Bhandari

1

Received: 22 August 2019 / Accepted: 16 April 2020

Ó The Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons of India 2020

Abstract

Introduction The spatial position and dimensions of oral

and pharyngeal soft tissues change post-mandibular

advancement (MA) surgery which involves changes in

position of soft palate, tongue and associated musculature.

There is no study which simultaneously evaluates changes

in tongue length and height post-MA surgery and correlates

these changes with changes in upper airway dimensions

and the amount of MA.

Materials and Methods Treatment records of 18 patients

that underwent MA with bilateral sagittal split ramus

osteotomy were evaluated at T1 (01 week before surgery)

and T2 (06 months post-surgery). Linear airway and ton-

gue measur ements were done on lateral cephalogram.

Mean volume and mean pharyngeal area values were

recorded from the acoustic pharyngometry (AP) records of

patients.

Results A statistically significant increase in tongue length

(P value \ 0.001) and nonsignificant change in tongue

height were observed at T2 ( P value[ 0.05). A statistically

significant increase in airway parameters recorded on both

lateral cephalogram and AP was observed at T2 (P value

\ 0.001). Correlation analysis did not show a statist ically

significant correlation of change in tongue length and

tongue height at T2 with the amount of MA, change in

airway parameters on lateral cephalogram and AP (P value

[ 0.05).

Conclusions Mandibular advancement surgery is a viable

option for improvement in pharyngeal airway in skeletal

Class II patients with retrognathic mandible. Changes in

tongue length observed in our study may correspond to the

stretch of protruders of tongue, especially genioglossus,

and may point toward possibl e relapse on a long-term

follow-up.

Keywords Mandibular advancement (MA) Obstructive

sleep apnea (OSA) Airway BSSRO

Introduction

Orthognathic surgeries involving maxilla and/or mandible

are mainly performed for bringing about positive

improvement in facial and smile aesthetics of the patient

apart from correction of various facial deformities [1, 2].

Maxillomandibular advancement by orthognathic surgery/

distraction osteogenesis (DO) is a well-documented treat-

ment modality for the management of obstructive sleep

apnea (OSA) secondary to hypoplastic/retr uded maxilla

and/or mandible. This treatment modality brings positive

improvement in airway by causing physical expansion of

the pharyngeal hard and soft tissues [3].

The surgeries involving mandibular setback (MS) are

well known to cause detrimental effects on upper airway

[4, 5]. The literature reveals that the spatial posi tion of oral

and pharyngeal soft tissues also changes post-surgery

which involves changes in the position of soft palate,

tongue and associated musculature [6, 7]. The surgeries

involving mandibular advancement (MA) cause forward

positioning of the tongue [4, 5]. This increases the

retropharyngeal airway space and may be helpful in indi-

viduals with compromised airway.

& N. K. Sahoo

1

Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Armed Forces

Medical College, Pune, India

2

Department of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics,

Armed Forces Medical College, Pune, India

123

J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s12663-020-01375-2

Few studies have been reported in the literature docu-

menting the changes in tongue dimensions and position

post-surgery in MA cases [1, 2, 4, 8]. There is no study

which concurrently associates these tongue changes with

the altered pharyngeal airway dimensions and amount of

MA. Keeping this background in mind, the present study

was conducted to evaluate the changes in tongue height and

length post-MA surgery and simultaneously correlate these

changes with changes in upper airway dimensions.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

Retrospective analytical study.

Study Sample

This study was carried out at the Department of

Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics of a tertiary care

teaching institution. The study sample included treatment

records of 18 patients randomly selected from the institu-

tional archives that underwent MA surgery with bilateral

sagital split ramus osteotomy (BSSRO) between Jan 01,

2014, and Dec 31, 2016, and met the inclusion criteria of

the study. Lateral cephalogram used in this study was

recorded with a standardized technique using the same

machine (model: ADVAPX cephalostat machine, com-

pany: Panorraitic System, printer: Fujifilms DRY PIX

7000). Acoustic pharyngometry (AP) was used as a non-

invasive tool for evaluating and com paring area and vol-

umetric changes in airway post-surgery. AP for all patients

was recorded by the same operator with

ECCOVISION

Ò

Acoustic Pharyngometer

TM

using the

standard protocol.

Inclusion Criteria

1. Adult patients aged 18–28 years (both the sex).

2. Complete set of pre- and post-treatment orthodontic

records available with minimum 06-month follow-up.

3. The impacted mandibular third molars removed min-

imum 06 months prior to surgery.

4. Cases who underwent only MA with BSSRO surgery

without genioplasty.

5. Skeletal Class II cases with ANB C 4° and

overjet C 4 mm.

6. Nonextraction cases with crowding/spacing B 5 mm.

Exclusion Criteria

1. Cleft/syndromic/pat ients with neuromuscular disor-

ders/psychiatric patients.

2. Patients with history of recurrent pharyngeal infec-

tions, enlarged tonsils/adenoids, or any other medical

condition compromising airway.

3. History of previous ortho-surgical treatment or trauma

to jaw bones.

4. Presence of ankyloglossia or any other disorder

affecting tongue morphology and/or mobility.

Study Design and Data Collection

The selected cases (18 patients, 10 males and 08 females)

underwent MA with BSSRO surgery and were treated with

a standardized ortho-surgical treatment protocol at the

institute. Pre- and postsurgical orthodontics was carried out

using 0.022 MBT pre-adjusted edgewise appliance with

standard wire sequence protocol.

The lateral cephalogram and AP were recorded at two

time frames:

T1 01 week before surgery.

T2 06 months post-surgery.

The lateral cephalograms were manually traced, and

pharyngeal airway and tongue measurements were done at

T1 and T2 (Table 1; Fig. 1). The pharyngeal airway

dimensions (mean volume and mean area) were recorded at

T1 and T2 from the AP records of the patients. The amount

of MA performed was recorded from the case sheets of the

patients. Changes in the above-mentioned parameters were

measured at T2 to know the changes in tongue and pha-

ryngeal airway dimensions post-surgery. The data were

collected and compiled in MS Excel work sheet and were

subjected to statistical analysis.

Statistical Analysis

The entire data were statistically analyzed using Statis tical

Package for Social Sciences (SPSS ver 21.0, IBM Corpo-

ration, USA) for MS Windows. The data on continuo us

variables were presented as mean and standard deviation

(SD). The statistical comparison of continuous variables

was done using paired t test. Pearson’s correlation was

carried out to study the correlations among the parameters

studied. The underlying normality assumption was tested

before subjecting each variable to t test and Pearson’s

correlation analysis. All the results are shown in tabular as

well as graphical format (using Box–Whisker plot) to

visualize the statistically significant difference more

clearly. In the entire study, the P values \ 0.05 were

J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg.

123

considered to be statistically significant. All the hypotheses

were formulated using two-tailed alternatives against each

null hypothesis (hypothesis of no difference).

Results

Post-surgical Changes in Parameters Studied

(Table 2)

The distribution of mean post-op (T2) tongue length

(70.56 mm, SD = 1.88 mm) was significantly higher

compared to mean pre-op (T1) tongue length (69.22 mm,

SD = 1.39 mm). The mean increase in tongu e length was

1.33 mm (SD = 0.87 mm), and this was statistically sig-

nificant (P value \ 0.001).

The distribution of mean post-op tongue height (29 mm,

SD = 1.58) did not differ significantly compared to mean

pre-op tongue height (29.33 mm, SD = 2.06 mm). The

mean decrease in tongue height was 0.33 mm with a SD of

1.50 mm, but this was not statistically significant (P value

[ 0.05).

The distribution of mean post-op airway parameters on

lateral cephalogram (SAS, PAS and MAS) was signifi-

cantly higher compared to mean pre-op airway parameters

(P value \ 0.001 for all).

The distribution of mean post-op parameters on AP

(mean volume and mean area) was significantly higher

compared to mean pre-op parameters (P value \ 0.001 for

all).

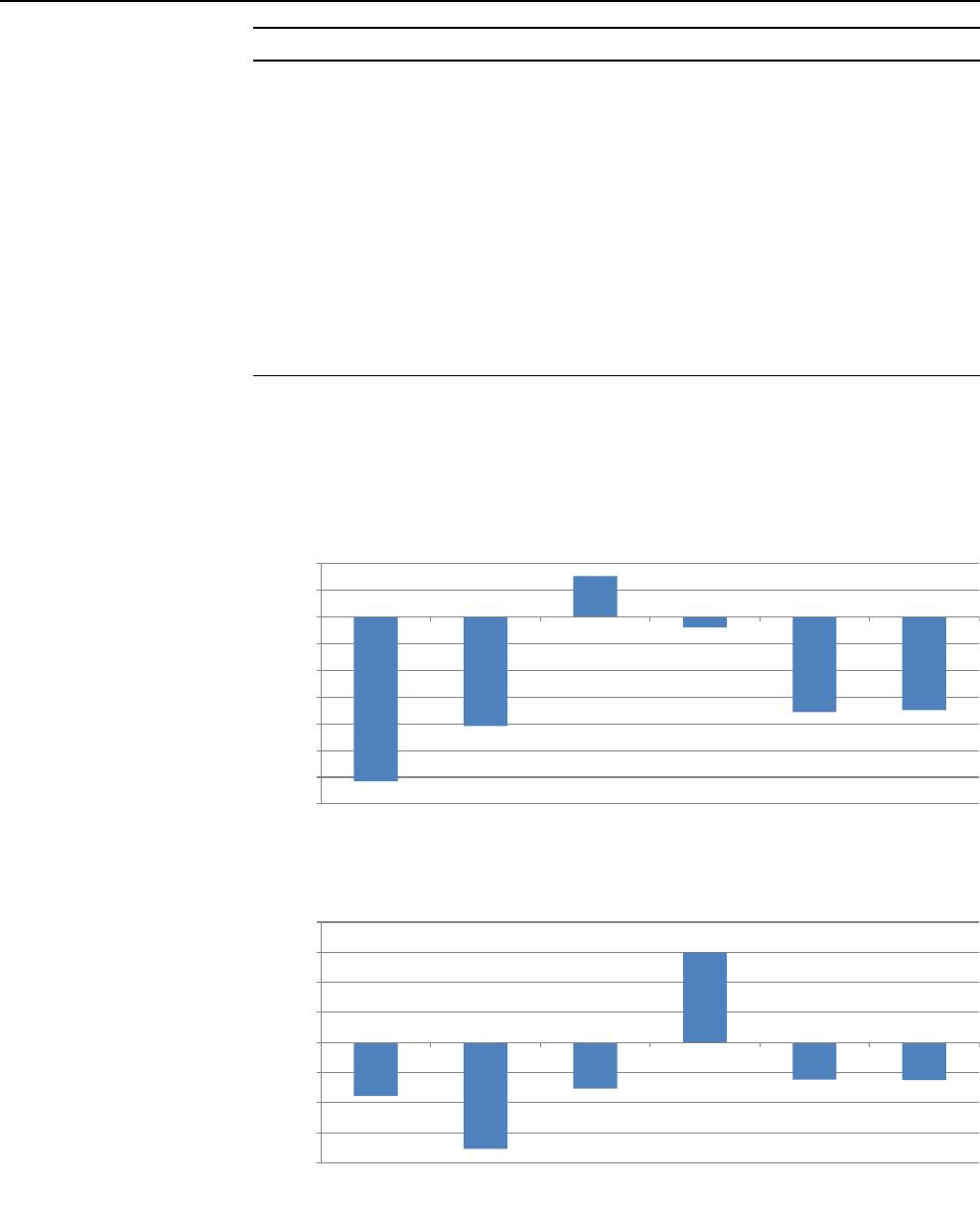

Correlation Analysis of Parameters Studied

with Change in Tongue Parameters (Table 3,

Figs. 2, 3)

The correlation analysis revealed that change in tongue

length (Fig. 2) and tongue height (Fig. 3) after surgery (at

T2) did not show statistically significant correlation with

the amount of MA, change in airway parameters (PAS,

SAS, MAS) on lateral cephalogram and change in AP

parameters (mean volume and mean area) in the study

sample (P value [ 0.05 for all).

Discussion

Various studies have demonstrated relationship of oral and

pharyngeal soft tissues with the craniofacial and dentofa-

cial structures. Any change in the skeletal tissues due to

growth, functional appliance therapy or orthognathic sur-

gery may cause spatial and dimensional changes in the

associated pharyngeal soft tissues (e.g., soft palate and

tongue) [9–12].

The tongue is an active and functional muscular organ

situated in the floor of the mouth. It is attached to the

lingual surface (genial tubercles) of the mandible, hyoid

bone, epiglottis and soft palate by various muscular

attachments [13, 14]. Various studies have shown that the

root of the tongue is more posteriorly positioned in skele-

tally class II subjects as compared to Class I and Class III

subjects. This compromises the pharyngeal airway, espe-

cially in the PAS and MAS region [14, 15]. MA causes

forward positioning of the tongue with a positive impact on

airway. This may also lead to changes in tongue dimen-

sions. Genioglossus muscle, which is the primary protruder

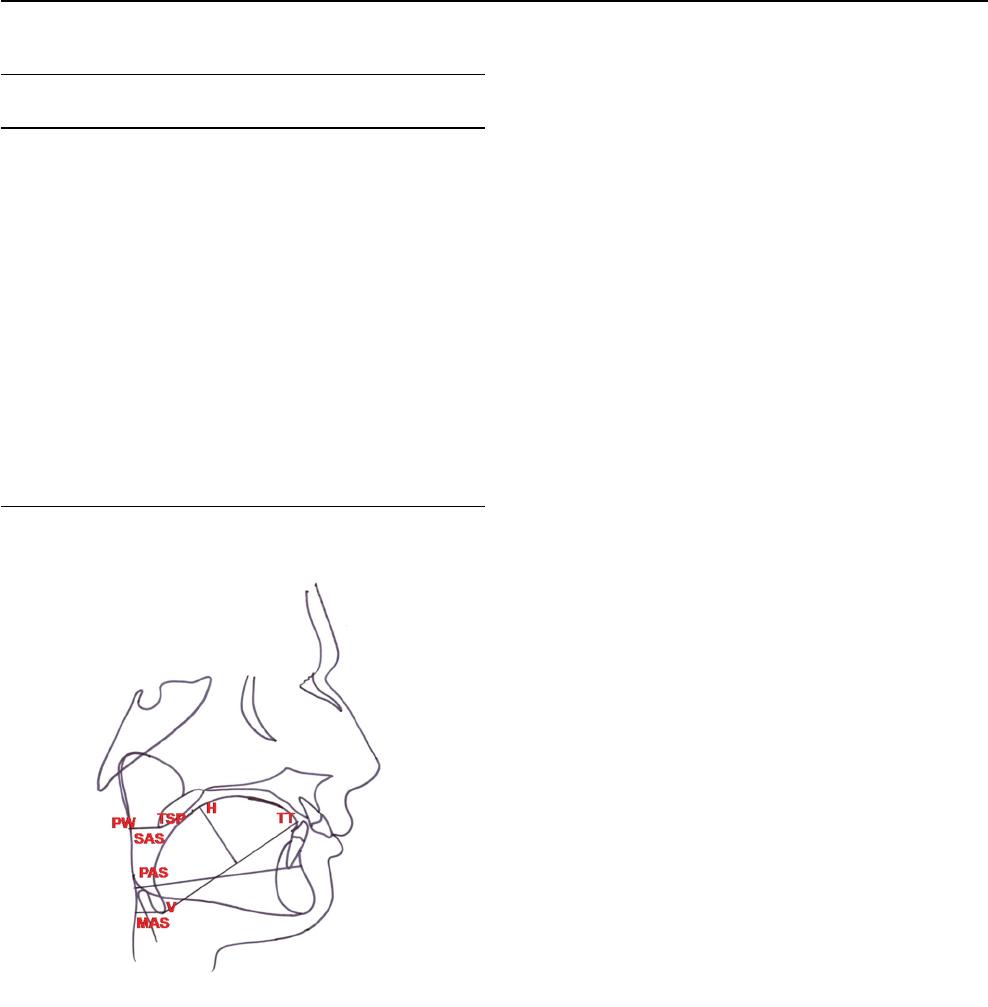

Table 1 Airway and tongue parameters studied on lateral

cephalogram

S.

no.

Parameter Measurement

1. Superior pharyngeal

airway space (SAS)

Linear distance measured from tip

of the soft palate (TSP) to the

nearest pharyngeal wall (PW)

2. Posterior airway space

(PAS)

Linear distance from posterior

margin of the base of the tongue

to the nearest pharyngeal wall on

Gonion-Point B (Go-B) line

3. Minimum/hypopharyngeal

airway space (MAS)

Minimum linear distance measured

from point V (intersection of

epiglottis and base of the tongue)

to the nearest pharyngeal wall

4. Tongue length (TL) Measured from point V to tip of the

tongue (TT)

5. Tongue height (TH) Perpendicular distance from the

highest point on the superior

surface of the tongue (H) to V-TT

line

Fig. 1 Landmarks used on lateral cephalogram

J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg.

123

muscle of the tongue, gets stretched during MA [16]. This

stretch may cause changes in tongue length and height, and

this may also be a cause of relapse in future. Based on these

inputs, this study was designed to evaluate the change s in

length and height of the tongue post-MA and also to find

correlation between these changes and airway parameters

assessed on lateral cephalogram and AP.

The literature reveals that lateral cepha logram is a reli-

able tool in determining airway dimensions [17, 18] with

efficacy comparable to computed tomography (CT) scans

[19]. A study [20] revealed that majority of the airway

landmarks can be reliably identified on a lateral cephalo-

gram. Also, it is routinely advised to all orthodontic

patients; hence, no additional cost and radiation exposure

are incurred to the patients. Therefore, lateral cephalogram

was used in our study to evaluate tongue and linear airway

dimensions.

AP is a noninvasive modality based on acoustic reflec-

tion technique for assessment of airway dimensions and

also to ascertain changes post-MA. It can be recorded chair

side at the orthodontic clinic, and its reliability is compa-

rable to CT scans [21]. Therefore, AP was used to assess

changes in mean volume and mean area in our study.

A statistically significant increase in tongue height on a

06-month follow-up after MA has been observed in one

study [22]. The change in tongue length was not statisti-

cally significant in this stud y at a 06-month follow-up.

These findings are not in agreement with our study wherein

a significant increase in tongue length has been observed

on a 06-month follow-up. The change in tongue height

was, however, not statistically significant in our study.

Prospective studies with a larger sample size may throw

more light in this regard.

Studies have shown that the tongue area remains

unchanged after the orthognathic surgery which provides a

more functional space to the tongue making it to assume a

more forward position [23]. This anterior positioning of the

tongue may be a reason for increased tongue leng th in our

study as the anterior portion of the tongue moves forward

during MA with stretching of the genioglossus mus cle.

The authors could not find any study which correlates

changes in tongue length and height with the amount of

MA. There is no literature available which correlates the

altered tongue dimensions post-MA with airway parame-

ters. AP was additionally used in our study to evaluate

changes in mean airway volume and area, and these

changes were also correlated with the altered tongue

dimensions. The correlation analysis revealed that change

in tongue length and height at T2 did not show statist ically

significant correlation with the amount of MA, change in

airway parameters on lateral cephalogram and changes in

mean volume and mean area evaluated by AP. A study [24]

observed mean anterior tongue displacement of 5.8 mm by

MA with DO and greater tongue displacement when DO

was accompanied with genioplasty. The tongue displace-

ment showed a strong correlation with the increase in PAS

width and anterior displacement of hyoid bone. A statisti-

cally significant increase in PAS and other linear, area and

volumetric parameters was also observed in our study at

T2. But in our study, the parameters were correlated with

tongue height and length rather than tongue displacement.

Table 2 Postsurgical changes in parameters studied

Parameter Mean SD

Tongue length (mm)

Pre-op 69.22 1.39

Post-op 70.56 1.88

P value

Pre versus post 0.002**

Tongue height (mm)

Pre-op 29.33 2.06

Post-op 29.00 1.58

P value

Pre versus post 0.524

NS

SAS (mm)

Pre-op 12.22 1.39

Post-op 13.22 1.56

P value

Pre versus post 0.003**

PAS (mm)

Pre-op 11.67 1.73

Post-op 13.56 1.81

P value

Pre versus post 0.002**

MAS (mm)

Pre-op 18.78 4.35

Post-op 20.06 4.45

P value

Pre versus post 0.013*

Mean vol (mm

3

)

Pre-op 25.11 5.04

Post-op 34.48 3.70

P value

Pre versus post 0.001***

Mean area (mm

2

)

Pre-op 2.53 0.51

Post-op 3.45 0.37

P value

Pre versus post 0.001***

Values are mean and SD, P values by paired t test

NS statistically nonsignificant

*P value \ 0.05; **P value \ 0.01; ***P value \ 0.001

J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg.

123

One study [25] observed no significant corr elation

between the pattern of tongue deformation on a dynamic

MRI and craniofacial structures (changes in tongue

volume, changes in airway volume and changes in SNA

and SNB angles). These results are similar to our study,

except that AP and lateral cepha logram were used to

Table 3 Correlation analysis of

parameters studied with change

in tongue parameters

Tongue parameter Correlation with r value P value

Change in tongue length Amount of advancement - 0.615 0.078

NS

Change in SAS - 0.408 0.275

NS

Change in PAS 0.152 0.697

NS

Change in MAS - 0.040 0.919

NS

Change in mean volume - 0.356 0.347

NS

Change in mean area - 0.349 0.357

NS

Change in tongue height Amount of advancement - 0.178 0.647

NS

Change in SAS - 0.354 0.351

NS

Change in PAS - 0.153 0.694

NS

Change in MAS 0.300 0.432

NS

Change in mean volume - 0.123 0.752

NS

Change in mean area - 0.125 0.749

NS

Correlation analysis by Pearson’s method

NS statistically nonsignificant

P value \ 0.05 is considered to be statistically significant correlation

*P value \ 0.05; **P value \ 0.01; ***P value \ 0.001

-0.615

-0.408

0.152

-0.04

-0.356

-0.349

-0.7

-0.6

-0.5

-0.4

-0.3

-0.2

-0.1

0

0.1

0.2

Amount of

advancement

Change in SAS Change in PAS Change in MAS Change in Mean

volume

Change in Mean

area

Pearson's r-value

Correlaon Analysis With Change in Tongue Length

Fig. 2 Correlation analysis of

parameters studied with change

in tongue length

-0.178

-0.354

-0.153

0.3

-0.123

-0.125

-0.4

-0.3

-0.2

-0.1

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

Amount of

Advancement

Change in SAS Change in PAS Change in MAS Change in Mean

volume

Change in Mean

area

Pearson's r-

value

Correlaon Analysis With Change in Tongue Height

Fig. 3 Correlation analysis of

parameters studied with change

in tongue height

J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg.

123

evaluate airway instead of dynamic MRI and these

parameters were correlated with changes in tongue height

and length instead of tongue deformation. Changes in SNA

and SNB angles were not evaluated in our study.

Conclusions

From the findings of this study, it can be concluded that

expansion of the skeletal tissues shows corresponding

changes in the oropharyngeal soft tissues. Mandibular

advancement surgery is a viable option for improvement in

pharyngeal airway in skeletal Class II patients with ret-

rognathic mandible. The changes in tongue length observed

in our stud y may correspond to the stretch of protruders of

the tongue, especially genioglossus, and may point toward

relapse on a long-term follow-up. Prospective studies with

a larger sample size and a long-term follow-up are required

to validate the findings of this study.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Ethics Statement The study design was approved by the institutional

ethical committee.

References

1. Eggensperger N, Smolka W, Iizuka T (2005) Long term changes

of hyoid bone position and pharyngeal airway size following

mandibular setback by sagittal split ramus osteotomy. J Cranio

Maxillo Fac Surg 33:111–117

2. Sahoo NK, Roy ID, Kulkarni V (2018) Mandibular setback and

its effects on speech. Oral Maxillofac Surg Cases. https://doi.org/

10.1016/j.omsc.2018.10.001

3. Zaghi S, Holty CEJ, Certal V et al (2016) Maxillomandibular

advancement for treatment of obstructive sleep apnea: a meta-

analysis. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 142(1):58–66

4. Marsan G, Oztas E, Cura N, Kuvat SV, Emekli U (2010) Changes

in head posture and hyoid bone position in Turkish Class III

patients after mandibular setback surgery. J Cranio Maxillo Fac

Surg 38:113–121

5. Chen F, Terada K, Hua Y, Saito I (2007) Effect of bimaxillary

surgery and mandibular setback surgery on pharyngeal airway

measurements in patients with class III skeletal deformities. Am J

Dentofac Orthop 131:372–377

6. Guven O, Saracoglu U (2005) Changes in pharyngeal airway

space and hyoid bone positions after body ostectomies and

sagittal split ramus osteotomies. J Craniofac Surg 16:23–30

7. Hasebe D, Kobayashi T, Hasegawa M et al (2011) Changes in

oropharyngeal airway and respiratory function during sleep after

orthognathic surgery in patients with mandibular prognathism. Int

J Oral Maxillofac Surg 40:584–592

8. Yoshida K, Rivera GA, Matsuo N et al (2000) Long-term prog-

nosis of BSSO mandibular relapse and its relation to different

facial types. Angle Orthod 70:220–226

9. Tangugsorn V, Skatvedt O, Krogstad O, Lyberg T (1995)

Obstructive sleep apnea: a cephalometric study. Part I. Cervico-

craniofacial skeletal morphology. Eur J Orthod 17:45–56

10. Tsuchiya M, Lowe AA, Pae EK, Fleetham JA (1992) Obstructive

sleep apnea subtypes by cluster analysis. Am J Orthod Dentofac

Orthop 101:533–542

11. Kaur S, Rai S, Sinha A, Ranjan V, Mishra D, Panjwani S (2015)

A lateral cephalogram study for evaluation of pharyngeal airway

space and its relation to neck circumference and body mass index

to determine predictors of obstructive sleep apnea. J Indian Acad

Oral Med Radiol 27:2–8

12. Turvey TA, Hall DJ (1984) Alteration in nasal airway resistance

following superior repositioning of the maxilla. Am J Orthod

Dentofac Orthop 45:109–114

13. Zhou L, Zhao Z, Lu D (2000) The analysis of the changes of

tongue shape and position, hyoid position in Class II, division 1

malocclusion treated with functional appliances (FR-I). Hua Xi

Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi 18(2):123–125

14. Tseng Y, Wu J, Chen C, Hsu K (2017) Correlation between

change of tongue area and skeletal stability after correction of

mandibular prognathism. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. https://doi.org/

10.1016/j.kjms.2017.03.008

15. Yamaoka M, Furusawa K, Uematsu T, Okafuji N, Kayamoto D,

Kurihara S (2003) Relationship of the hyoid bone and posterior

surface of the tongue in prognathism and micrognathia. J Oral

Rehabil 30:914–920

16. Takahashi S, Kuribayashi G, Ono T, Ishiwata Y, Kuroda T (2005)

Modulation of masticatory muscle activity by tongue position.

Angle Orthod 75:35–39

17. Malkoc S, Usumez S, Nur M, Donaghy CE (2005) Reproducibility

of airway dimensions and tongue and hyoid positions on lateral

cephalograms. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop 128:513–516

18. Aboudara C, Nielsen I, Huang JC, Maki K, Miller AJ, Hatcher D

(2009) Comparison of airway space with conventional lateral

headfilms and 3 dimensional reconstruction from cone beam com-

puted tomography. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop 135:468–479

19. Riley RW, Powell NB, Guilleminault C (1990) Maxillary,

mandibular, and hyoid advancement for treatment of obstructive

sleep apnea: a review of 40 patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg

48:20–26

20. Miles PG, O’Reilly M, Close J (1995) The reliability of upper

airway landmark identification. Aust Orthod J 14:3–6

21. Agarwal SS, Jayan B, Kumar S (2015) Therapeutic efficacy of a

hybrid mandibular advancement device in the management of

obstructive sleep apnea assessed with acoustic reflection tech-

nique. Indian J Dent Res 26:86–89

22. Achilleos S, Krogstad O, Lyberg T (2000) Surgical mandibular

advancement and changes in uvuloglossopharyngeal morphology

and head posture: a short- and long-term cephalometric study in

males. Eur J Orthod 22:367–381

23. Turnbull NR, Battagel JM (2000) The effects of orthognathic

surgery on pharyngeal airway dimensions and quality of sleep.

J Orthod 27:235–247

24. Sriram SG, Andrade NN (2014) Cephalometric evaluation of the

pharyngeal airway space after orthognathic surgery and distrac-

tion osteogenesis of the jaw bones. Indian J Plast Surg

47:346–353

25. Lowth A, Juge L, Knapman F et al (2018) Dynamic MRI tongue

deformation patterns during mandibular advancement and asso-

ciations with craniofacial anatomy in OSA. J Sleep Res. https://

doi.org/10.1111/jsr.169_12766

Publisher’s Note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to

jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg.

123