ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Emotion Regulation in Depression and Anxiety: Examining

Diagnostic Specificity and Stability of Strategy Use

Catherine D’Avanzato

•

Jutta Joormann

•

Matthias Siemer

•

Ian H. Gotlib

Published online: 4 April 2013

Ó Springer Science+Business Media New York 2013

Abstract Many psychological disorders are characterized

by difficulties in emotion regulation. It is unclear, however,

whether different disorders are associated with the use of

specific emotion regulation strategies, and whether these

difficulties are stable characteristics that are evident even

after recovery. It is also unclear whether the use of specific

strategies is problematic across all disorders or whether

disorders differ in how strongly strategy use is associated

with symptom severity. This study investigated (1) the

specificity of use of emotion regulation strategies in indi-

viduals diagnosed with current major depressive disorder

(MDD), with social anxiety disorder (SAD), and in never-

disordered controls (CTL); and (2) the stability of strategy

use in formerly depressed participants (i.e., remitted;

RMD). Path analysis was conducted to examine the rela-

tion between strategy use and symptom severity across

diagnostic groups. Compared to the CTL group, partici-

pants in both clinical groups endorsed more frequent use of

rumination and expressive suppression, and less frequent

use of reappraisal. Specific to SAD were even higher levels

of expressive suppression relative to MDD, as well as a

stronger relation between rumination and anxiety levels. In

contrast, specific to MDD were even higher levels of

rumination and lower levels of reappraisal. Interestingly,

elevated rumination, but not decreased reappraisal, was

found to be a stable feature characterizing remitted

depressed individuals. These results may provide insight

into ways in which emotion regulation strategy use main-

tains psychological disorders.

Keywords Depression Social anxiety Emotion

regulation Rumination Suppression Reappraisal

Introduction

Difficulties in emotion regulation are proposed to be

associated with a range of emotional disorders such as

anxiety disorders and major depressive disorder (MDD)

(Campbell-Sills and Barlow 2007; Hofmann et al. 2012;

Mennin and Farach 2007). Emotion regulation is defined as

the use of cognitive or behavioral strategies in order to

modify the circumstances in which an emotion occurs, the

experience of an emotional response (including its intensity

and duration), or the way in which an emotion is overtly

expressed (Gross 2002). Previous research suggests that

emotion regulation strategies differ in their effectiveness in

reducing negative affect (e.g. Gross 1998; Campbell-Sills

et al. 2006b); consequently, these strategies may also differ

in their association with emotional disorders. Few studies,

however, have examined individual differences in the use

of specific emotion regulation strategies across carefully

diagnosed psychological disorders. This study examined

whether participants diagnosed with depression and social

anxiety disorder differ in the frequency of their use of

emotion regulation strategies. In addition, we examined

group differences in the association of the use of these

strategies with the severity of depression and anxiety

symptoms.

A strategy that has been linked to negative outcomes for

individuals’ mood and functioning is rumination, or the

tendency to think repetitively about one’s negative mood

C. D’Avanzato (&) J. Joormann M. Siemer

Department of Psychology, University of Miami, 5665 Ponce de

Leon Blvd, Coral Gables, FL 33124, USA

e-mail: [email protected]

I. H. Gotlib

Department of Psychology, Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA,

USA

123

Cogn Ther Res (2013) 37:968–980

DOI 10.1007/s10608-013-9537-0

state and its causes and consequences (Nolen-Hoeksema

1991). Rumination can lead to increases in negative mood

(see review by Nolen-Hoeksema et al. 2008) and is asso-

ciated with the activation of negative cognitions in memory

(Watkins and Teasdale 2001; Lyubomirsky and Nolen-

Hoeksema 1995). Rumination also impairs problem solv-

ing and interpersonal functioning (Lyubomirsky et al.

1999; Nolen-Hoeksema and Davis 1999). Expressive sup-

pression is frequently discussed as another maladaptive

emotion regulation strategy (Gross 1998). Expressive

suppression involves attempting to control emotional

responses by avoiding expressing them outwardly. This

strategy has been shown to be less effective in relieving

negative emotions and to be associated with increased

physiological arousal (Gross 1998; Campbell-Sills et al.

2006a, b; Hofmann et al. 2009). In addition, suppression is

cognitively taxing, resulting in impaired memory and

cognitive functioning (Richards and Gross 2000; Egloff

et al. 2006). In contrast, reappraisal is widely regarded as

an adaptive emotion regulation strategy, defined as think-

ing about a stressful event from a different perspective in a

way that minimizes its negative impact (Gross 1998; Gross

and John 2003). Reappraisal effectively reduces negative

affect and is not associated with the increased or sustained

physiological reactivity observed when individuals use

suppression (Augustine and Hemenover 2009; Denson

et al. 2012; Gross 1998; Gross and John 2003; Shiota and

Levenson 2012). Reappraisal has been demonstrated to be

less cognitively taxing than is suppression (Egloff et al.

2006; Richards and Gross 2000) and to be related to better

physiological stress recovery (Jamieson et al. 2012; Mauss

et al. 2007).

Given the differential effectiveness of these various

emotion regulation strategies, it is possible that habitual

use of specific strategies plays an important role in the

onset and maintenance of clinical depression and other

emotional disorders (Hofmann et al. 2012). Numerous

studies have in fact demonstrated an association between

rumination and depression (Nolen-Hoeksema et al. 2008).

Specifically, rumination is correlated with a greater number

of recurrences of depressive episodes over time, and in some

studies longer duration of depressive episodes (Nolen-

Hoeksema 1991; Roberts et al. 1998). Moreover, longitu-

dinal studies have indicated that rumination can predict

increased risk for developing depression in response to

stressful events (Moberly and Watkins 2008). Beyond the

well-established association between rumination and

depression, more frequent use of expressive suppression

and less frequent use of reappraisal have been found in

individuals with elevated symptoms of depression (e.g.

Moore et al. 2008; Nezlek and Kuppens 2008). In addition,

a recent meta-analysis found elevated depression scores to

be associated not only with greater use of rumination, but

also with greater suppression and, although to a lesser

extent than the maladaptive strategies, less reappraisal

(Aldao et al. 2010).

To date, studies that simultaneously examine more than

one disorder and more than one type of emotion regulation

strategy are rare, particularly studies utilizing diagnosed

samples (Aldao et al. 2010). Thus, it is unclear whether the

habitual use of certain strategies, such as rumination and

expressive suppression, is specific to depression or is a

general feature of psychopathology. The lack of studies

examining more than one emotion regulation strategy and

more than one diagnostic category also makes it difficult to

examine whether the use of specific emotion regulation

strategies is generally adaptive or maladaptive, or in con-

trast whether the consequences of using a particular strat-

egy are moderated by characteristics of individuals and

situations in which the strategies are deployed. For exam-

ple, it is possible that rumination increases negative affect

and cognition in general and, therefore, is associated with

the severity of symptoms of anxiety and depression not

only in depressed, but also in non-disordered participants.

Alternatively, for non-depressed individuals, rumination

may resemble reflection and problem-solving and, there-

fore, may not be strongly associated with symptoms of

depression and anxiety. Indeed, recent studies have shown

that strategies generally thought to be ‘‘maladaptive’’ are

associated with positive outcomes when used by individ-

uals with particular characteristics or in particular situa-

tions. For example, Liverant et al. (2008) reported that

expressive suppression was effective in reducing sadness

for individuals with low, but not with moderate to high,

levels of anxiety. Likewise, recent evidence suggests that

individuals’ variability in strategies used across a range of

situations, or their emotion regulation flexibility, may be

important to consider, with individuals drawing from

multiple strategies across different situations shown to

exhibit lower symptom levels (Aldao and Nolen-Hoeksema

2012b). To answer these questions, however, it is necessary

to examine multiple strategies and disorders simulta-

neously in order to understand how patterns of use across

these strategies relate to various forms of psychopathology,

a question which has not generally been addressed to date.

One exception is a study conducted by Aldao and Nolen-

Hoeksema (2010) which examined the relation between

rumination, thought suppression and reappraisal with

symptoms of depression, anxiety and disordered eating.

The authors found that all three emotion regulation strat-

egies loaded significantly onto one latent factor of cogni-

tive emotion regulation and that the cognitive emotion

regulation factor was significantly associated with symp-

toms of all three disorders. However, this study was limited

by use of an undiagnosed college sample, results of which

do not necessarily generalize to clinical populations.

Cogn Ther Res (2013) 37:968–980 969

123

It is also possible that clinical groups find it difficult to

implement adaptive strategies such as reappraisal effec-

tively and, thus, may exhibit a weaker relation between

reappraisal use and symptom severity. In their meta-anal-

ysis, Aldao et al. (2010) found that reappraisal was more

weakly associated with symptoms of various types of

psychopathology including depression and anxiety; this

finding has been replicated in several recent studies (Aldao

and Nolen-Hoeksema 2010; Aldao and Nolen-Hoeksema

2012a), and one interpretation that has been put forth is that

this may reflect difficulties with effective reappraisal or

interference related to elevated use of rumination and

suppression among individuals with psychopathology

(McRae et al. 2012). Consistent with this idea, Sheppes

et al. (2011) have found evidence that reappraisal may

become more taxing and less helpful when individuals are

regulating intense emotion, as is typically the case in the

context of emotional disorders. Differences between

depressed and non-depressed individuals in neural corre-

lates of reappraisal have also been documented and are

associated with less effective down-regulation of negative

affect (Johnstone et al. 2007; Siegle et al. 2007). Similarly,

one recent study demonstrated that, among college students

who had recently experienced a stressor, higher levels of

depressive symptoms were associated with reduced effec-

tiveness of reappraisal in a laboratory film task (Troy et al.

2010). McRae et al. (2012) found that individuals higher in

well-being exhibited more effective reappraisal in response

to a laboratory task, and reappraisal effectiveness on this

task interestingly was associated with more frequent

habitual reappraisal use. However, results are mixed and

some studies have found that reappraisal is equally effec-

tive in reducing subjective distress among individuals with

psychopathology as healthy controls (Aldao and Mennin

2012; Campbell-Sills et al. 2011). Studies that examine

differences in the strength of relations between particular

emotion regulation strategies and symptom severity across

different diagnostic groups are therefore critical because

they may illuminate potential diagnostic group differences

in the role of these strategies in the development and

maintenance of these disorders.

Recent studies have shown that difficulties with emotion

regulation also play a central role in anxiety disorders. In

the present study we examined individuals with SAD as a

comparison group because it is one of the most prevalent

anxiety disorders which often co-occurs with and precedes

MDD (Beesdo et al. 2007). MDD and SAD are both

marked by significant interpersonal impairment (Murray

and Lopez 1997; Schneier et al. 1994) and decreased

positive affectivity (Brown et al. 1998; Kashdan and Steger

2006). Previous findings suggest that SAD, like MDD, is

characterized by elevated rumination, often occurring in

anticipation of feared social situations (Vassilopoulos

2005), or following feared situations in the form of post-

event processing (Edwards et al. 2003; Abbott and Rapee

2004). Recent studies have also found evidence of diffi-

culties with reappraisal in SAD (Goldin et al. 2009a; b).

More frequent use of expressive suppression, however,

may be particularly prevalent in individuals with SAD and

is held to play a central role in the maintenance of this

disorder (Erwin et al. 2003; Kashdan and Steger 2006;

Turk et al. 2005).

The current study examines the self-reported use of

several emotion regulation strategies (rumination, reap-

praisal, expressive suppression) in individuals diagnosed

with current MDD, with MDD in full remission (RMD),

with social anxiety disorder (SAD), and with healthy

controls with no history of any DSM-IV Axis I disorder

(CTL). The first aim of this study was to examine the

specificity to MDD of the use of each strategy. We pre-

dicted greater use of maladaptive strategies (rumination,

expressive suppression) and less frequent use of reap-

praisal, an adaptive strategy, in both the MDD and SAD

groups, relative to the CTL group. We predicted further

that rumination would be specific to MDD

1

; that is, MDD

participants would report higher levels of rumination than

would SAD participants. In contrast, given the centrality of

suppression in recent conceptualizations of SAD, we pre-

dicted that we would find higher levels of suppression

among SAD participants relative to MDD participants. As

both MDD and SAD have been associated with reduced

reappraisal use and effectiveness and studies contrasting

these two disorders are lacking, analyses of the specificity

of reappraisal to MDD or SAD were exploratory.

The second aim of this study was to examine the sta-

bility of the use of specific strategies of emotion regulation

with recovery from a depressive episode. We expected to

find that increased use of maladaptive strategies and

decreased use of adaptive strategies are stable character-

istics of individuals at risk for depression and, therefore,

that the RMD participants do not differ from the MDD

participants in their reported frequency of use of these

strategies. Finally, we examined whether the relation

between frequency of strategy use and severity of symp-

toms of depression and anxiety is comparable among the

different groups. In particular, we conducted exploratory

analyses to investigate whether MDD and SAD participants

differ in the magnitude of the relation between the use of

emotion regulation strategies and symptom severity in

order to gain insight into potential unique factors that might

contribute to the maintenance of these disorders.

1

We use the term specificity to refer to relative specificity, indicating

that use of a particular strategy is more elevated in one group than

another, rather than present in one group and absent in another.

970 Cogn Ther Res (2013) 37:968–980

123

Method

Participants

Participants were 551 individuals with a mean age of

36 years who were recruited from the community. Four

groups of participants completed this study: 189 partici-

pants diagnosed with current MDD; 48 participants diag-

nosed with at least one past episode of MDD who were

currently in remission (RMD); 58 individuals diagnosed

with SAD; and 256 CTLs with no history of Axis-I dis-

order. Participants were recruited from the community

through online and newspaper advertisements.

2

Partici-

pants initially completed a brief telephone interview to

determine eligibility. Exclusion criteria included severe

head trauma and learning disabilities, a history of bipolar

disorder, psychotic symptoms, and alcohol and substance

use disorder within the past 6 months. Individuals who met

inclusion criteria were invited to come into the laboratory

to complete a diagnostic interview.

During the first study session, the Structured Clinical

Interview for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of

Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition Text Revision (DSM-

IV-TR; American Psychiatric Association 2000) (SCID;

First et al. 1997) was administered by trained interviewers

with extensive diagnostic interview experience. To assess

inter-rater reliability, an independent trained rater who was

blind to group membership evaluated 15 randomly selected

audiotapes of SCID interviews with depressed and social

phobic participants, and with nonpsychiatric controls. In

all 15 cases, diagnoses of depression, social phobia, and

nonpsychiatric control matched the diagnosis made by the

original interviewer, j = 1.00. This indicates excellent

inter-rater reliability, although we should note that the

interviewers used the ‘‘skip out’’ strategy of the SCID, which

may have reduced the opportunities for the independent

raters to disagree with the diagnoses. Participants were

included in the MDD group if they met DSM-IV-TR criteria

for current MDD but not SAD, in the SAD group if they met

DSM-IV-TR criteria for current SAD but not MDD, and in the

RMD group if they met DSM criteria for a past Major

Depressive Episode. In addition, a slightly modified version of

the SCID was used to verify that each participant in the RMD

group had fully recovered from depression, following guide-

lines recommended by the NIMH Collaborative Program on

the Psychobiology of Depression (e.g., Keller et al. 1992): 8

consecutive weeks with no more than 2 symptoms of no more

than a mild degree (i.e., ratings of 1 [no symptoms] or 2

[minimal symptoms, no impairment]). Finally, participants

were included in the CTL group if they did not meet DSM

criteria for any current or past DSM-IV-TR Axis I disorder.

Measures

Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ; Gross and John

2003)

The ERQ is a 10-item self-report measure of an individual’s

habitual use of expressive suppression and reappraisal to reg-

ulate emotion. This measure is composed of a 4-item expres-

sive suppression subscale and a 6-item reappraisal subscale.

Each item is rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly

disagree; 7 = strongly agree). Subscales were summed, with

higher scores indicating greater use of the strategy. The ERQ

has demonstrated high internal consistency (.79 for reappraisal

and .73 for suppression) and test–retest reliability of .69 for

both subscales (Gross and John 2003). The present sample

demonstrated adequate internal consistency for both the reap-

praisal (a = .84) and suppression subscales (a = .68).

Ruminative Responses Scale (RRS; Nolen-Hoeksema and

Morrow 1991; Treynor et al. 2003)

The tendency to respond to negative events or emotions by

ruminating, or repetitively thinking about these events or

the reasons one is upset, was assessed using the 22-item

RRS. Each item is rated on a 4-point Likert scale

(1 = almost never; 4 = almost always). The RRS has

demonstrated adequate test–retest reliability (r = .67) and

internal consistency (a = .90) (Nolen-Hoeksema 2000), as

well as good predictive validity (Nolen-Hoeksema and

Morrow 1991). With regards to the present study sample,

the RRS demonstrated good internal consistency (a = .89).

Beck Depression Inventory, Second Edition (BDI-II; Beck

et al. 1996)

The BDI-II is a 21-item scale that assesses self-reported

severity of depressive symptoms. Each item assesses the

2

The data were collected as the first part of ongoing data collection

in our labs. Participants were assigned to participate in additional

tasks after completion of the diagnostic interview and the question-

naires, including tasks which were part of various sub- studies of

depression and social anxiety. Separate advertisements targeting

individuals currently experiencing (1) depression, (2) social anxiety,

and (3) individuals with no current or past depression or psychiatric

concerns (controls) were posted throughout the community. Individ-

uals in the remitted depressed group were drawn from individuals

responding to the depression ads who did not currently meet MDD

criteria, but met criteria for a past episode. The ads described the

symptoms of each disorder and invited individuals currently experi-

encing these symptoms to contact the lab if interested in taking part in

the study. Throughout the course of enrollment, a greater number of

depression ads were posted, reflecting a greater focus of studies in our

lab on depression. This contributed to different sample sizes across

diagnostic groups. Given the ads were identical with the exception of

the symptoms being described, the nature of the ads should not have

resulted in differential representativeness of the diagnostic groups.

Cogn Ther Res (2013) 37:968–980 971

123

severity of a specific symptom, with ratings ranging from 0

to 3. The BDI-II is a widely used self-report measure of

depression with high internal consistency, ranging from .73

to .92 (Beck et al. 1996).

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory-Trait (STAI-T; Spielberger

et al. 1983)

Self-reported trait anxiety, the general tendency to expe-

rience anxiety in daily life, was assessed using the 20-item

STAI-T. Each item is rated on a 4-point scale (1 = almost

never; 4 = almost always). The STAI-T has shown

excellent internal consistency (a = .90) and test–retest

reliability ranging from .73 to .86 (Spielberger et al. 1983).

Results

Participant Characteristics

Table 1 presents demographic and clinical characteristics

for the four groups of participants. The mean age of par-

ticipants was 35.95 (SD = 11.12), and one-third of the

participants were male. As expected, the four groups dif-

fered significantly in BDI-II scores, F(3,511) = 399.76,

p \ .001, with the MDD group obtaining significantly

higher BDI-II scores than did the CTL, RMD, and SAD

groups. The SAD participants had higher BDI-II scores

than did the RMD participants, who in turn had higher

BDI-II scores than did the CTL participants. The four

diagnostic groups also differed in trait anxiety levels,

assessed by the STAI-T, F(3,435) = 280.04, p \ .001. All

four groups differed significantly from each other on STAI-

T scores in the order MDD, SAD, RMD, and CTL.

Unexpectedly, diagnostic groups differed in mean age;

however, age was not found to be significantly associated

with use of any of the three emotion regulation strategies

we investigated (r’s =-.03–.02, all ps [.05).

Given that we focused only on one anxiety disorder in

the present study, we also examined rates of comorbidity

of other anxiety disorders besides SAD among the MDD

and SAD groups. One quarter (24.5 %) of depressed

participants had at least one or more current comorbid

anxiety disorders. In contrast, 25.9 % of socially anxious

individuals and 8.4 % of participants in the RMD group

met criteria for a comorbid anxiety disorder. MDD, RMD

and SAD groups did not differ significantly in the pres-

ence of comorbid anxiety disorders, V

2

= 7.43, p [ .05,

thus differences between the MDD, RMD and SAD

groups in emotion regulation were not confounded by

differential rates of other comorbid anxiety disorders in

these groups.

Use of Emotion Regulation Strategies

Table 1 presents mean scores on the RRS, ERQ-suppres-

sion, and ERQ-reappraisal measures by diagnostic group.

3

A multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was

conducted to test the hypothesis that the CTL, RMD,

MDD, and SAD groups differ in the frequency with which

they report using each strategy. The MANOVA yielded

significant differences among the groups in the use of these

strategies, Wilks’s K = .48, F(9,978.5) = 38.55, p =

.000, g

2

= .22. Analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were

conducted on each dependent variable as follow-up tests to

the MANOVA. The three ANOVAs all yielded significant

group differences (RRS: F(3,538) = 175.06, p \ .001;

ERQ-suppression: F(3,413) = 7.59, p \ .001; ERQ-reap-

praisal: F(3,410) = 23.56, p \ .001). In follow-up analy-

ses for each emotion regulation strategy, we first contrasted

both clinical groups (MDD and SAD) with the CTL group.

As expected, compared with the CTL participants, partic-

ipants with a disorder (MDD and SAD participants com-

bined), exhibited higher scores on the RRS, t(492) =

17.69, p \ .001, d = 1.75, and the ERQ-suppression scale,

t(366) = 4.54, p \ .001, d = .50, and lower scores on the

ERQ reappraisal scale, t(368) = 6.70, p \ .001, d = .76.

We then conducted planned comparisons to evaluate

whether the use of rumination is specific to MDD and

expressive suppression specific to SAD. Indeed, the MDD

group obtained significantly higher scores on the RRS than

did the SAD group, t(244) = 6.19, p \ .001, d = .88.

Moreover, there was evidence for specificity of expressive

suppression to SAD: SAD participants exhibited signifi-

cantly higher ERQ-suppression scores than did MDD par-

ticipants, t(190) = 3.00, p = .003, d = .45. Finally, MDD

participants had lower levels of ERQ-reappraisal than did

participants diagnosed with SAD, t(188) = 2.02, p = .04,

d = .31.

To test the third hypothesis that greater use of rumination

and expressive suppression, and decreased use of reap-

praisal, is stable following recovery from MDD, planned

comparisons were conducted contrasting MDD, RMD, and

CTL groups in their mean use of each strategy. In partial

support of our hypothesis, the RMD participants obtained

higher scores on the RRS than did CTLs, t(294) = 6.27,

p \ .001, d = 1.01, but had lower RRS scores than did the

3

As data on suppression and reappraisal was not collected until mid-

way into enrollment for the study, this resulted in smaller sample

sizes for analyses of these variables. Individuals missing this data

were included in analyses of diagnostic group differences in

rumination frequency, as well as in the SEM analyses, as missing

data on these emotion regulation variables was missing at random.

972 Cogn Ther Res (2013) 37:968–980

123

MDD participants, t(234) = 7.52, p \ .001, d = 1.16.

4

With respect to expressive suppression, RMD participants

did not differ from either the MDD, t(188) = .17, p = .87,

or CTL, t(223) = 1.41, p = .16, participants. Contrary to

hypotheses, RMD and CTL participants did not differ in

their ERQ-reappraisal scores, t(222) = 1.12, p = .27,

suggesting that less use of reappraisal is not a stable feature

that endures beyond depressive episodes. Indeed, the RMD

participants obtained higher scores on the ERQ-reappraisal

scale than did MDD participants, t(186) = 4.33, p \ .001,

d = .72.

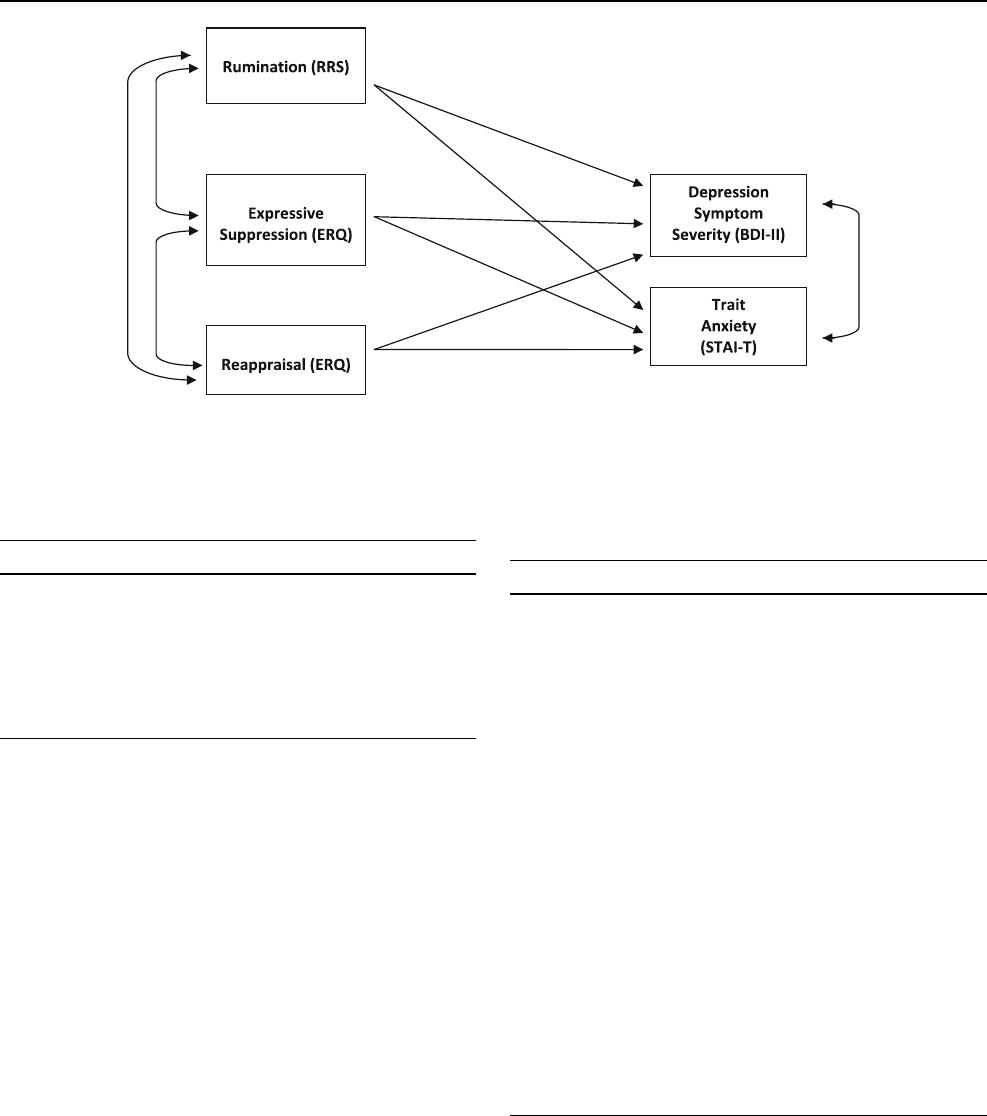

Specificity: Group Differences in Relations Among

Strategy Use and Depression and Anxiety Symptoms

To examine whether the use of specific emotion regulation

strategies is generally adaptive or maladaptive, we further

examined whether the groups differed in their relation

between strategy use and severity of anxiety and depres-

sion symptoms by conducting a path analysis using M plus

Version 4 (Muthe

´

n and Muthe

´

n 2006). Specifically, we

conducted multiple group comparisons to test whether the

degree to which RRS, ERQ-suppression, and ERQ-

reappraisal scores predict BDI and STAI-T scores differs

among groups (see Kline 2005 for a description of this

technique). This approach involved first testing the fit of a

base model, in which mean RRS score, ERQ-suppression

score, and ERQ-reappraisal scores predict BDI and STAI-T

scores (see model displayed in Fig. 1). In the base model,

paths from each strategy (RRS, ERQ-suppression, ERQ-

reappraisal) to BDI and STAI-T, as well as relations among

emotion regulation strategies, were estimated for each

diagnostic group separately. We then compared the base

model to a model in which different diagnostic groups were

constrained to be equal on a given path linking an emotion

regulation strategy with BDI/STAI-T scores. We con-

ducted a Chi square test to determine whether constraining

groups to be equal in these paths yielded a significantly

higher model fit value, indicating a poorer fit to the data,

compared to the base model.

The base model included three inter-correlated predic-

tors (RRS score, ERQ-suppression score, ERQ-reappraisal

score), each of which was proposed to predict both BDI-II

and STAI-T scores. This model provided an excellent fit to

the data, v

2

(20, N = 546) = 14.54, p = .80, comparative

fit index = 1.00, root mean square error of approxima-

tion = .00. As expected, higher RRS as well as lower

ERQ-reappraisal scores predicted significantly higher BDI-

II and STAI-T scores for all four diagnostic groups. The

path from ERQ-suppression to BDI-II, and to STAI-T,

however, was not significant for CTLs, MDDs, and SADs;

for RMDs the relation between ERQ-suppression and

STAI-T scores was statistically significant.

Table 2 displays complete results for the best-fitting final

model that was retained for each diagnostic group after

conducting all multi-group comparisons; in these models,

paths on which diagnostic groups did not differ were con-

strained to be equal among groups, while paths on which

groups were found to differ were estimated separately

Table 1 Mean emotion regulation strategy use and demographic characteristics by diagnostic category

CTL (N = 256) RMD (N = 48) MDD (N = 189) SAD (N = 58)

Age 35.10 (11.47)

b

36.40 (8.90)

bc

38.33 (10.73)

c

31.56 (10.87)

a

% Women 65

a

68

a

69

a

67

a

% Caucasian 64

a

77

a

74

a

71

a

RUM 1.54 (.46)

c

2.04 (.51)

b

2.64 (.53)

a

2.17 (.53)

b

SUPPRESS 13.63 (4.39)

c

14.64 (4.78)

bc

14.89 (5.23)

b

17.23 (5.57)

a

REAP 29.85 (6.05)

a

28.79 (6.22)

ab

23.67 (7.51)

c

26.08 (6.95)

b

STAIT 30.50 (6.82)

d

38.86 (11.12)

c

56.98 (10.10)

a

50.70 (10.55)

b

BDI 2.53 (3.88)

d

7.75 (10.66)

c

27.90 (9.07)

a

12.57 (9.51)

b

Diagnostic categories sharing a subscript are not significantly different from one another (p \ .05; e.g. MDD and SAD groups differed in mean

rumination levels, but RMD and SAD groups did not differ from one another). Values in parentheses represent standard deviations

STAIT Spielberger Trait Anxiety Inventory-Trait, BDI Beck Depression Inventory-II, RUM rumination (Ruminative Responses Scale), Suppress

expressive suppression (Emotion Regulation Questionnaire), Reap reappraisal (Emotion Regulation Questionnaire)

4

As some prior studies have found different subcomponents of

rumination to differ in relation to symptoms of psychopathology, we

also examined diagnostic group differences in brooding, a subscale of

the RRS assessing more maladaptive rumination, and reflection, the

RRS subscale assessing a more adaptive form of rumination.

Brooding and reflection were significantly correlated in the present

sample, r = .47, p = .00. The MDD and SAD groups were elevated

on both the brooding and reflection subscales compared to CTLs.

However, the MDD compared to SAD group was elevated only in

brooding, t(244) = 3.47, p = .00, not reflection, t(244) = .1.65,

p = .10. In addition, compared to the CTL group, t(297) = 5.23,

p = .00, only elevated brooding, but not reflection, t(294) = 1.84,

p = .07, was seen in the RMD group. Both brooding and reflection

showed significant positive correlations with BDI and STAI-T levels

for all diagnostic groups, with the exception that only brooding, but

not reflection, was correlated with BDI and STAI-T in the RMD

group.

Cogn Ther Res (2013) 37:968–980 973

123

across those groups. We first examined whether the diag-

nostic groups differ in the degree to which RRS predicts

BDI-II. Elevated RRS scores more strongly predicted ele-

vated BDI-II scores among both MDD and SAD partici-

pants than CTL participants (see Tables 2, 3). There was no

evidence for specificity, however, in that SAD versus MDD

individuals did not differ from one another in the path from

RRS to BDI-II. With regard to the relation between RRS

levels and trait anxiety, however, we did find evidence for

specificity. RRS scores more strongly predicted elevated

STAI-T levels in SAD than in CTL participants. Further,

RRS predicted STAI-T levels more strongly among SAD

than among MDD participants.

ERQ- suppression (expressive suppression) was not a

significant predictor of scores on the BDI-II or STAI-T,

regardless of diagnosis. Therefore, we did not conduct

multiple group comparisons including ERQ-suppression.

Finally, we examined whether ERQ-reappraisal differen-

tially predicts BDI-II and STAI-T across different diag-

nostic categories. We found the relation between elevated

ERQ- reappraisal and lower BDI-II scores to be stronger

among both MDD and SAD participants than CTL par-

ticipants but did not find evidence of specificity, with MDD

and SAD participants not differing from one another in this

path. With regard to trait anxiety, self-reported reappraisal

predicted lower STAI-T levels to a comparable degree in

CTL, MDD and SAD groups.

Fig. 1 Association among self-reported use of rumination, expressive suppression, and reappraisal with depression and anxiety symptom

severity

Table 2 Path coefficients from ER strategies to BDI and STAI-T

levels by diagnostic category

CTL RMD MDD SAD

Rumination to BDI .35**

a

.41**

ab

.49**

b

.54**

b

Rumination to STAIT .57**

a

.42**

a

.49**

a

.76**

b

Reappraisal to BDI -.17*

a

-.20**

b

-.28**

b

-.29**

b

Reappraisal to STAIT -.27**

a

-.19**

a

-.25**

a

-.23**

a

R square (BDI) .17 .23 .35 .36

R square (STAI-T) .42 .29 .33 .61

Path coefficients are standardized B’s. Diagnostic categories sharing a

subscript do not significantly differ from one another

* p \ .05, ** p \ .01

Table 3 Multiple groups comparisons results: Chi square difference

values between diagnostic groups constrained versus unconstrained in

paths from ER strategies to BDI and STAI-T

Comparison Dv

2

Rumination to BDI

CTL versus MDD 10.91***

CTL versus SAD 18.74***

MDD versus SAD 3.15

CTL versus RMD 3.52

RMD versus MDD .02

Rumination to STAIT

CTL versus MDD .03

CTL versus SAD 8.73**

MDD versus SAD 17.03***

CTL versus RMD .26

RMD versus MDD .00

Reappraisal to BDI

CTL versus MDD 5.89*

CTL versus SAD 5.86*

MDD versus SAD .31

CTL versus RMD 7.52**

RMD versus MDD .27

Reappraisal to STAIT

All groups constrained versus unconstrained 1.23

* p \ .05, ** p \ .01, ** p \ .001

974 Cogn Ther Res (2013) 37:968–980

123

Stability: Differences Across MDD, RMD, and CTL

Groups in the Strength of Association Among Emotion

Regulation Strategies and Symptom Severity

To test whether the strength of the relation between emo-

tion regulation strategy use and symptom severity remains

stable following a depressive episode, multigroup com-

parisons among MDD, RMD, and CTL groups were con-

ducted (see Table 3). We first examined whether the

stronger relation between RRS scores and symptoms

observed in the MDD group would also be evident in the

RMD group, indicating stability in these paths. In fact,

RMD participants did not differ significantly from MDD

participants in the path from RRS to BDI-II scores, nor

from RRS to STAI-T scores. However, evidence for sta-

bility was mixed in that RMD participants also did not

differ significantly in these paths from CTLs. With regards

to reappraisal, we found evidence for stability among the

RMD group in the relation between reappraisal and BDI

scores, but not reappraisal and STAI-T scores. ERQ-reap-

praisal more strongly predicted lower BDI-II scores among

RMD participants than among CTLs, with RMD and MDD

participants not differing from one another. RMD, MDD,

and CTL groups did not differ in the path between ERQ-

reappraisal and STAI-T, and no groups differed from one

another.

Discussion

Previous studies have helped to elucidate differences

among various emotion regulation strategies in their

effectiveness in regulating negative affect. This study

expanded on previous research by examining the frequency

of use of emotion regulation strategies in diagnosed sam-

ples and by addressing whether greater use of maladaptive

strategies, and less use of an adaptive strategy, is specific to

SAD or MDD, or a general feature of psychopathology.

Given that both MDD and SAD participants reported

greater use of expressive suppression and rumination and

less frequent use of reappraisal than did CTLs, the use of

maladaptive strategies is, to some degree, a general feature

of these disorders. Diagnostic groups also differed, how-

ever, in their use of rumination, reappraisal and expressive

suppression, providing support for diagnostic specificity. In

particular, MDD participants reported more frequent use of

rumination and less frequent use of reappraisal than did

SAD participants, who in turn reported more use of

expressive suppression than did their MDD counterparts.

The finding that rumination is particularly common in

the MDD group is not surprising given that the majority of

research on rumination has demonstrated that rumination

plays a significant role in risk for and maintenance of this

disorder (Nolen-Hoeksema et al. 2008). SAD is also

characterized by self-focused attention and negative self-

evaluation, however, and in recent years research has

emerged showing evidence of elevated rumination in

individuals with SAD in anticipation of (Vassilopoulos

2005) and following feared social situations (Edwards et al.

2003), even when controlling for depressive symptoms

(e.g. Abbott and Rapee 2004). Rumination in SAD and

MDD may involve similar processes characterized by

repetitive, self-focused thinking about personal shortcom-

ings. Indeed, in this study, rumination was associated with

more severe depressive symptoms in both groups. Rumi-

nation in SAD, however, frequently termed post-event

processing or post-event rumination, typically focuses on

perceived shortcomings, or negative images of oneself or

one’s performance, during a recent social-evaluative situ-

ation and may differ slightly in its content from depressive

rumination. Post-event rumination, however, has been

found to have similar consequences as depressive rumi-

nation, prolonging anxiety and increasing negative cogni-

tions surrounding a social situation (Wong and Moulds

2009; Morgan and Banerjee 2008). This is consistent with

the results obtained in this study that the relation between

rumination and anxiety was specifically strong in the SAD

participants. These results suggest that rumination in SAD

plays an important role in maintaining both elevated

depression and anxiety.

The results of this study also show that socially anxious

individuals attempt to suppress their emotions to a signif-

icantly greater degree than depressed individuals. These

findings are consistent with results of a recent study that

documented that expressive suppression is more common

among university students who are high versus low in

social anxiety; this study further demonstrated that greater

use of expressive suppression was mediated by beliefs

about the consequences of expressing emotions (Spokas

et al. 2009). Concerns about physical symptoms of anxiety,

including sweating, blushing, and shaking, being noticed

and judged negatively by other people are common in, and

may be unique to, SAD (Scholing and Emmelkamp 1993).

This finding is also consistent with cognitive models of

SAD, which predict that worries about the negative con-

sequences of anxiety symptoms becoming visible to others

may prompt socially anxious people to suppress their

anxiety as a safety behavior to prevent embarrassment

(Clark and Wells 1995; Rapee and Heimberg 1997). Such

safety behaviors are predicted to play a central role in the

maintenance of SAD by preventing disconfirmation of

fearful thoughts. It is important to note that a greater ten-

dency to suppress emotion has also been found to be

associated with other anxiety disorders aside from SAD,

such as panic disorder (Baker et al. 2004; Tull and Roemer

2007) and PTSD (Moore et al. 2008). In fact, reducing use

Cogn Ther Res (2013) 37:968–980 975

123

of suppression and replacing it with more adaptive strate-

gies, such as acceptance and approach-related behaviors, is

a central target of acceptance-based psychotherapy

approaches for a range of psychological disorders (e.g.

acceptance and commitment therapy, ACT, Hayes et al.

1999). Therefore, in future studies it will be important to

examine differences in the implementation and conse-

quences of this strategy across multiple anxiety disorders in

comparison to depression.

Interestingly, in this study the frequency of use of

expressive suppression was not associated with increased

severity of depression or anxiety symptoms in the SAD

group. This result is surprising given previous studies that

have found an association among use of suppression and

increased depression and anxiety, and given that elevated

suppression frequency was found among the SAD partici-

pants relative to MDD and CTL participants (Aldao et al.

2010). As we examined a clinical sample of individuals

with SAD who on average were elevated in suppression, it

is possible that restricted variability in suppression within

the SAD group and the relatively small SAD group size

prevented the detection of an association with symptom

severity. It is also possible that this reflects a limitation in

our measure of anxiety severity and that stronger relations

between suppression and symptom severity would be seen

with a measure which assesses social anxiety specifically,

as opposed to a more general measure of anxiety such as

the STAI. Alternatively, it is possible that suppression is

not uniformly related to greater symptom severity among

all individuals and that we may have omitted important

variables moderating the relation between suppression and

symptom severity; in fact, prior studies have found that

suppression frequency is not uniformly related to negative

outcomes. Eftekhari et al. (2009), who classified partici-

pants on the basis of their frequency of both suppression

and reappraisal use and examined associations with

symptom levels, found that people classified as frequent

users of both strategies represented the most common

pattern of emotion regulation. Although people high in

reappraisal and low in suppression reported the lowest

symptom levels among the categories examined, people

high in use of both strategies also reported effective ER and

relatively low symptom levels. Thus, a subset of individ-

uals who are coping effectively may frequently draw from

both suppression and reappraisal (also see Lam et al. 2009,

who found a positive correlation between reappraisal and

suppression use). Future research is needed to examine the

role of expressive suppression in SAD and the relation

between the use of this emotion regulation strategy and

symptom severity.

Decreased use of reappraisal was reported by both SAD

and MDD participants. Unexpectedly, the results of this

study also provide support for the specificity of reappraisal,

in that depressed individuals reported using reappraisal

significantly less frequently than did socially anxious par-

ticipants. One explanation for this finding is that individ-

uals with MDD may have more difficulty reappraising,

which could result in less frequent use of reappraisal.

Previous studies have documented impairment in the

ability to inhibit the processing of negative emotional

material in MDD, a deficit that is also associated with

greater use of rumination in MDD. In a recent study,

Joormann and Gotlib (2010) demonstrated that difficulty

with inhibition, present to a greater degree in MDD par-

ticipants, was also associated with less frequent use of

reappraisal. However, results did not support the hypoth-

esis that reappraisal exhibits a weaker inverse relationship

with depression and anxiety symptoms among depressed

individuals, which could reflect reduced effectiveness of

this strategy.

The present results also demonstrate that some diffi-

culties with emotion regulation documented in MDD are a

stable feature that endures beyond a depressive episode.

Specifically, RMD participants reported higher levels of

rumination than did CTLs. This finding is consistent with

the results of a recent study reporting greater use of

rumination in RMD individuals than in never-depressed

controls (Ehring et al. 2008). This finding is important

because the overuse of strategies, such as rumination, is

often conceptualized as a vulnerability factor which con-

tributes to the development and maintenance of depression,

yet few studies to date have investigated whether prob-

lematic emotion regulation strategies precede or persist

beyond the acute depressive episode. Our finding suggests

that the use of rumination may not be merely a symptom of

MDD, but may possibly play a role in the development and

maintenance of this disorder. It is important to point out the

limitations of using a remitted depression design to infer

that the use of rumination is a risk factor which may be

causally related to depression, however (see review by Just

et al. 2001). The experience of depression may lead to

important changes in cognitive and biological processes, or

scarring, which in turn fuels increased rumination per-

sisting beyond the offset of the disorder. However, our

finding is consistent with a growing literature supporting

that by adolescence elevated rumination serves as a trait-

like vulnerability factor which is associated with increased

risk for subsequent increases in depression (Abela et al.

2012; Hankin 2009; Hilt et al. 2010). High trait rumination

has been linked to stable characteristics such as deficits in

executive control processes (Hilt et al. 2012; Joormann

2006; Joormann and Gotlib 2010). Moreover, given the

highly recurrent nature of MDD, elevated rumination

enduring beyond the offset of a depressive episode may be

an important factor influencing depressed individuals’ risk

for future recurrences. Interestingly, however, RMD and

976 Cogn Ther Res (2013) 37:968–980

123

CTL participants did not differ in their use of reappraisal,

suggesting it is possible that difficulty reappraising is

confined to the acute depressive episode. Reappraisal may

become more cognitively demanding and thus more diffi-

cult to effectively implement when it is used to regulate

intense emotions (Sheppes et al. 2011). Reappraisal may

therefore be easier for individuals to implement once they

are no longer depressed, accounting for the increased use of

this strategy reported in the RMD relative to the MDD

group. It is further possible that individuals in the RMD

group may have been more likely to receive prior treatment

focused on increasing reappraisal use, such as cognitive

therapy; as we do not have data on participants’ prior

experience in cognitive therapy, this would be an inter-

esting question for future research. As previously noted,

few studies have examined reappraisal ability in clinically

depressed samples, and even less is known about both the

use and effectiveness of reappraisal in remitted individuals.

Reappraisal has been shown to be less consistently related

to symptoms of psychopathology (Aldao et al. 2010), and

some studies have failed to find reduced reappraisal ability

in clinical samples (e.g. Aldao and Mennin 2012). Con-

verging with these prior studies, the magnitude of relations

between reappraisal use and both BDI and STAI in the

present study were all small. The consequences of reap-

praisal may be more sensitive to contextual factors and

other individual traits, thus it may be premature to con-

clude that difficulties with reappraisal do not characterize

remitted individuals. Clearly, more research on the stability

of the use of emotion regulation strategies is needed.

Despite the strengths of this study, perhaps most notably

that it permitted the examination of the role of multiple

strategies in different diagnostic groups, we should note

several limitations. First, this study relied on self-report

measures of the frequency of strategy use. There are many

challenges in assessing the dispositional use of emotion

regulation strategies, such as limitations in individuals’

awareness and ability to report accurately on their daily

strategy use. Therefore, we cannot be sure that participants’

self-reported use of emotion regulation strategies corre-

sponds to characteristics of their actual use of these strat-

egies in their daily life. In addition, it has been argued that

single emotion regulation strategies are not likely to be

universally adaptive or maladaptive, but that a person’s

ability to select strategies which appropriately fit a situation

at hand and to flexibly draw from a wide variety of strat-

egies are more important indicators of adaptive emotion

regulation (e.g. Hofmann et al. 2012). An experience

sampling approach would allow investigation of these

variables, as well as ensuring greater generalizability of

results to participants’ day to day lives. In addition, given

that the present study was cross-sectional and did not

include laboratory measures which assess diagnostic group

differences in the deployment and effectiveness of each

strategy, this limits our ability to draw conclusions about

specific ways in which elevated use of specific maladaptive

strategies and underuse of reappraisal may contribute to

MDD and SAD. However, self-reported use of these

strategies has been found in recent studies to be related to

other laboratory measures of emotion regulation, including

psychophysiological measures of stress response (e.g.

Mauss et al. 2007) and recently, to enhanced reappraisal

ability (McRae et al. 2012).

Second, as the STAI is a general measure of anxiety

severity, as opposed to a specific measure of social anxiety

symptoms, this presented a limitation in drawing conclu-

sions about emotion regulation specificity to MDD versus

SAD. For instance, it is possible that use of a SAD symp-

tom-specific measure would have yielded significant rela-

tions between suppression and symptom severity. In

addition, depression is often characterized by elevated

general anxiety symptoms, and the MDD group was com-

parably elevated on the STAI as the SAD group in the

present study. In contrast, as the BDI is a measure that is

more specific to MDD, it is difficult to gauge whether MDD

and SAD groups differed in clinical severity, which may

also be associated with the use of emotion regulation

strategies. Therefore, it would be important to replicate our

results using a measure of anxiety specific to social anxiety

symptoms. Third, while the use of ‘‘pure’’ MDD and SAD

groups was necessary in the present study in order to

address the question of which features of emotion regula-

tion are specific to one disorder versus the other, a limitation

of this approach is reduced external validity. Given the high

rates of comorbidity of MDD and SAD, it would be ideal in

future studies also to include a comorbid MDD-SAD group

in order to better understand the role of emotion regulation

in this subpopulation. In addition, due to the nature of

participant recruitment, we obtained small SAD and RMD

samples relative to the MDD and CTL groups, reducing

power to detect significant effects in these groups particu-

larly within the multiple group comparisons. Finally, it is

possible that restricted variability in anxiety and depression

symptom severity within the CTL group compared to the

clinical groups may have contributed to the weaker rela-

tionships between emotion regulation strategy use and

symptom severity observed within this group.

This study increases our knowledge of the use of emo-

tion regulation strategies in MDD and SAD. The results

indicate that individual differences in the use of emotion

regulation strategies may play a significant role in the

maintenance of both SAD and MDD, although these dis-

orders may differ in the types of strategies most commonly

used and in the mechanisms underlying the relation among

strategy use and symptom severity. To summarize, both

SAD and MDD are characterized by increased use of both

Cogn Ther Res (2013) 37:968–980 977

123