International Journal of Control, Automation and Systems 19(X) (2021) 1-9

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12555-020-0092-7

ISSN:1598-6446 eISSN:2005-4092

http://www.springer.com/12555

Adaptive Torsional Vibration Control of the Nonlinear Rolling Mill Main

Drive System with Performance Constraints and Sensor Errors

Cheng Qian, Liuliu Zhang*, and Changchun Hua

Abstract: This paper studies the torsional vibration suppression control problem for the nonlinear rolling mill main

drive system with performance constraint requirements and unknown measurement sensitivities. Firstly, considering

the nonlinear friction between the roll gaps, a torsional vibration model of the main drive system of rolling mill is

established. Then, with the asymmetric performance constraints transformation, the motor torque control law is

proposed based on backstepping algorithm. By introducing an adaptive bound estimation approach, the multiple

unknown parameters caused by the sensor sensitivities can be approximated with very few adaptive laws. The

dynamic surface technology is introduced to simplified the control design procedure and solve the computational

explosion problem. It is strictly proved that the resulting closed-loop system is stable in the sense of uniformly

ultimately boundedness and both transient and steady-state performances of the load speed are preserved. Finally,

the simulation is provided to show the validity and the advantages of the proposed techniques.

Keywords: Dynamic surface control, nonlinear rolling mill main drive system, performance constraints, sensor

errors, torsional vibration suppression.

1. INTRODUCTION

Rolling mill vibration is one of the important reasons

that affects the equipment condition with the rolling speed

improving [1, 2]. According to the rolling vibration cat-

egories, it can be divided into torsional vibration [3–5],

vertical vibration [6–8], horizontal vibration [9–11] and

coupling vibration [12]. In the rolling process, when the

transmission shaft is subject to the dynamic load or the

fluctuation of roll gap lubrication state, it is easy to cause

the rolling mill torsional vibration. The torsional vibra-

tion not only affects the stability of rolling process and

the quality of rolled strip, but also causes the connecting

shaft of the main drive system damage, which brings great

economic losses to the enterprise.

The modeling of rolling mill vibration is the prerequi-

site of torsional vibration suppression. Therefore, many

scholars have carried out the research work of torsional vi-

bration modeling. Considering the mechanical and electri-

cal coupling characteristics of the rolling mill main drive

system, [13] established a torsional vibration model, and

the influence of different mechanical and electrical param-

eters on the vibration displacement characteristics was an-

alyzed. [14] put forward the rolling mill coupled vibration

dynamic model, and analyzed the influence of process pa-

rameters and structure parameters on the system stability.

A multi-stand chatter model was established by combin-

ing the inter-stand tension variations and the time-delay

effect of the strip transportation. At the same time, the

influence of friction conditions on vibration was studied,

and the optimal friction conditions were given [15]. Lu et

al. [16] proposed a dynamic increment model for chatter

in a Universal Crown Control mill, and analyzed the exis-

tence of the Hopf bifurcation point and bifurcation charac-

teristics of the rolling mill vibration system. However, the

above references do not involve the vibration suppression

control design problem.

In the past decades, research on advanced control al-

gorithms has been received considerable attention, for ex-

ample H

∞

analysis, output feedback control, adaptive con-

trol and online policy iteration optimal control [17–21].

For the torsional vibration suppression control, based on

torsional vibration model, Yang et al. [22] proposed a

speed controller based on extended state observer and lin-

ear quadratic, and applied it to the torsional vibration con-

trol. A robust and fast speed control approach based on

state-space method was applied to the torsional system

[23]. Fujikawa et al. [24] adopt the active control method,

which used a negative speed feedback to reduce mill vi-

bration. Amer et al. [25] put forward a speed controller

Manuscript received February 6, 2020; revised May 7, 2020; accepted June 21, 2020. Recommended by Associate Editor Xiao-Heng Chang

under the direction of Editor Guang-Hong Yang. This work was supported in part by the National Key R&D Program of China under

Grant 2018YFB1308300, in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (61803326, 6182500417, 61751309, 61673335, and

61933009).

Cheng Qian, Liuliu Zhang, and Changchun Hua are with the Department of Automation, Yanshan University, Qinhuangdao 066004, China

(e-mails: {chengqianysu, liuliuysu}@163.com, [email protected]).

* Corresponding author.

c

ICROS, KIEE and Springer 2020

2 Cheng Qian, Liuliu Zhang, and Changchun Hua

and used an observer based on state feedback compensator

in the main control loop to suppress vibration of rolling

mill main drive system. Dhaouadi et al. [26] designed a

linear time invariant (LTI) robust controller for rolling mill

torsional vibration. However, the above mentioned liter-

atures do not consider the performance constraints prob-

lem. The prescribed performance control is a pretty impor-

tant tool for improving system performance and dealing

with the performance constraints problem. This idea was

first proposed in [27], and was widely used in the control

of various nonlinear systems [28–33]. But up to now, the

prescribed performance control has not been applied to the

torsional vibration system. Actually, the load speed of the

main drive system is always subject to performance re-

quirements in practice. The torsional suppression control

algorithm designed with the performance constrains can

ensure that the attenuation rate of the vibration, steady-

state error, and overshoot are limited in the given range.

The physical parameters of the torsional vibration sys-

tem such as roll speed, motor torque and motor speed

are collected by corresponding sensors in the rolling pro-

cess. The sensitivity error of sensor is inevitable because

of manufacturing and the system true state cannot be ob-

tained by measurement. Inaccurate measurements used in

controller designing may worsen the performance of the

system, and even cause the system unstable. To deal with

this problem, [34, 35] studied control design for nonlinear

systems only with the unknown output measurement sen-

sitivity. Recently, robust stabilization controller was pro-

posed for high-order pth nonlinear systems with unknown

state sensitivities and was applied in humanoid robot ma-

nipulation in [36]. How to design the torsional vibration

suppression controller with state sensor errors and perfor-

mance constraint requirements is still a challenging sub-

ject.

Inspired by the above motivations, we investigate the

robust torsional vibration suppression control for the

rolling mill main drive system with performance con-

straints and unknown sensor errors in this paper. The con-

tributions of this article are as follows: i) Considering the

nonlinear friction of roll and strip, a nonlinear torsional

vibration model of the rolling mill main drive system is

established. ii) A new torsional vibration suppression al-

gorithm is developed for the rolling mill main drive sys-

tem with the untrue measurement information that is ob-

tained by sensors with the unknown measurement sensi-

tivities for the first time. iii) To improve the attenuation

performance of torsional vibration, the adaptive perfor-

mance constraints control is considered for the load speed,

and the attenuation rate, steady-state error, and overshoot

can be limited to the given range.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: In Section

2, we give the mathematical modeling and the problem de-

scription. In Section 3, the motor torque is designed based

on backstepping approach and dynamic surface control

technique with performance constraints. Then simulations

show the effectiveness of the proposed method in Section

4. Finally, the paper is concluded in Section 5.

2. MATHEMATICAL MODELING AND

PROBLEM FORMULATION

2.1. Mathematical modeling

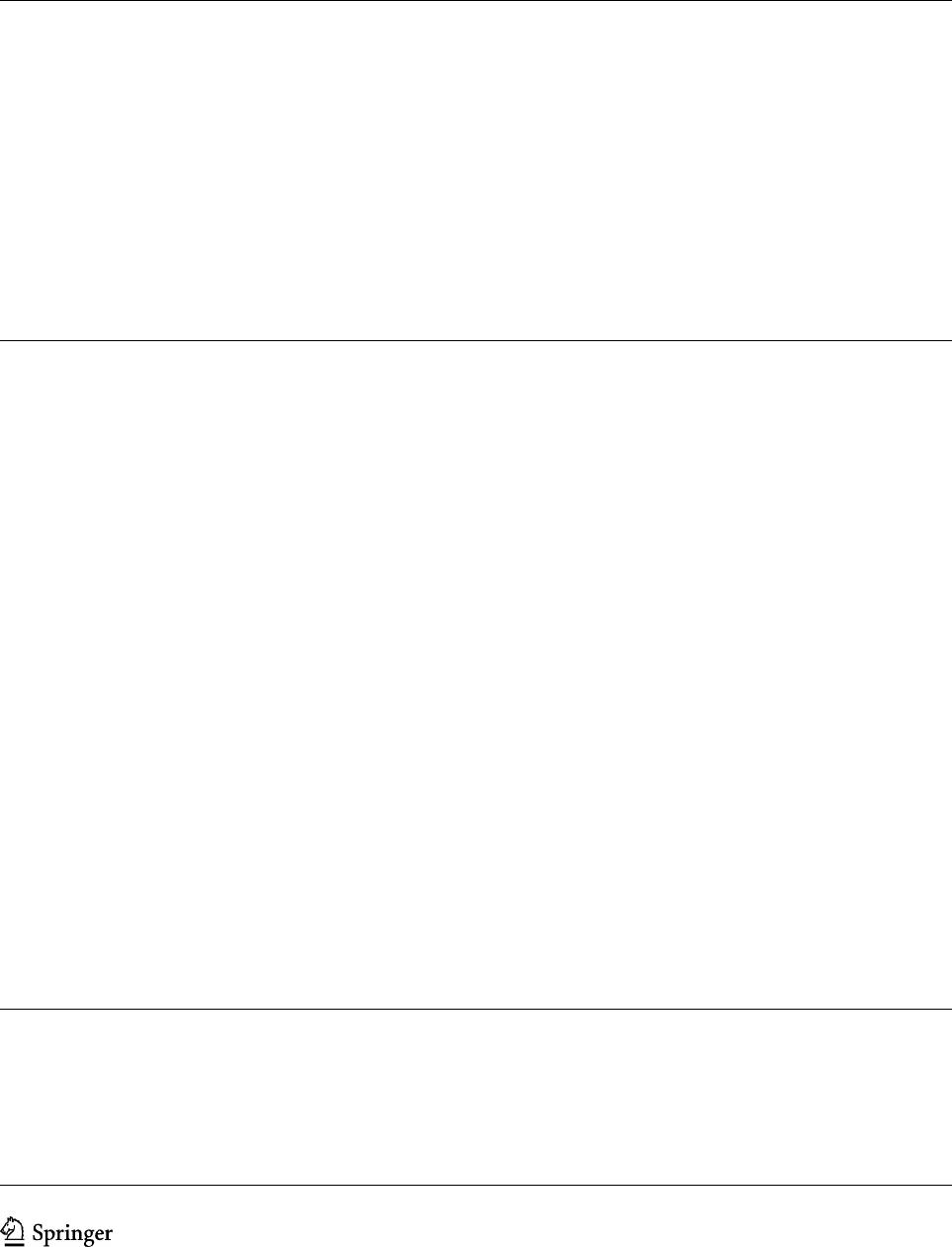

The rolling mill main drive system consists of motor,

speed reducer, connecting shaft and roll (Fig. 1). In the

main drive system, the mass of the motor, speed reducer,

and roll is large and the elasticity is small, while the con-

necting shaft has large elasticity and small mass. There-

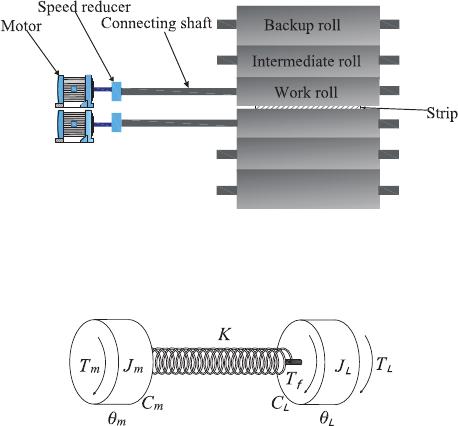

fore, the system is simplified as a mass spring damping

system composed of inertia elements without stiffness and

elastic elements without mass, as shown in Fig. 2, where

T

m

is the motor torque, T

L

is the load torque, T

f

is the fric-

tion torque, J

m

,J

L

is the moment of inertia of motor and

load, C

m

,C

L

is the damping coefficient of motor and load,

θ

m

is the rotation angle of motor, θ

L

is the rotation angle of

roll, K is the stiffness coefficient of the connecting shaft.

According to Lagrange’s equation, the dynamic equa-

tion of the main drive system of rolling mill can be written

as

(

J

m

¨

θ

m

+C

m

˙

θ

m

+ K (θ

m

−θ

L

) = T

m

,

J

L

¨

θ

L

+C

L

˙

θ

L

+ K (θ

L

−θ

m

) = T

L

+ T

f

.

(1)

During the rolling process, products with different

thicknesses and specifications will cause uncertain distur-

bances to the load torque. Therefore, we can express the

load torque as follows:

T

L

= T

L1

+ T

LD

, (2)

Fig. 1. Structure composition diagram of the rolling mill

main drive system.

Fig. 2. Schematic diagram of the main drive system.

Adaptive Torsional Vibration Control of the Nonlinear Rolling Mill Main Drive System with Performance ... 3

where T

L1

is the load torque of steady rolling; T

LD

is the

disturbance of load torque during rolling with different

specifications and T

LD

is bounded, thus T

L

≤

¯

T

L

.

The friction torque of roll can be expressed as follows:

T

f

= µPR, (3)

where µ is the friction coefficient between strip and roll,

P is rolling force, R is work roll radius. The friction coef-

ficient at the roll gap during rolling can be expressed as

µ = ae

−bv

L

+c

, (4)

where a,b,c are variable parameters and v

L

is roll rotation

linear speed and v

L

=

˙

θ

L

Rwith

˙

θ

L

is roll angular velocity.

Take (3)-(4) into (1) and expand the friction coefficient

according to Taylor’s formula, it can be obtained

J

m

¨

θ

m

+C

m

˙

θ

m

+ K (θ

m

−θ

L

) = T

m

,

J

L

¨

θ

L

+C

L

˙

θ

L

+ K (θ

L

−θ

m

)

= T

L

+ aRPe

c

−aRPe

c

bR

˙

θ

L

−

1

2

b

2

R

2

˙

θ

2

L

.

(5)

2.2. Problem formulation

By defining x

1

=

˙

θ

L

,x

2

= θ

m

−θ

L

,x

3

=

˙

θ

m

, we can ob-

tain that

˙x

1

=

K

J

L

x

2

+

T

L

J

L

+

aPRe

c

(1 −bRx

1

+

b

2

R

2

2

x

2

1

) −C

L

x

1

J

L

,

˙x

2

= x

3

−x

1

,

˙x

3

=

T

m

J

m

−

C

m

J

m

x

3

−

K

J

m

x

2

.

(6)

In this paper, the actual measurement values of states

are obtained by sensors with sensor errors, which are mod-

eled as follows:

ˇx

i

= λ

i

x

i

, (7)

where λ

i

6= 0(i = 1,2,3) are unknown constants. Without

loss of generality, we assume the unknown measurement

sensitivities λ

i

> 0.

When torsional vibration occurs in the system, the load

speed will be unstable. If we design an appropriate motor

torque to make the load speed stable at a constant value,

then we can effectively suppress the occurrence of tor-

sional vibration. Although there is a sensor error between

the measured load speed and the actual speed, if we can

stabilize the measured load speed at a stable value, the

torsional vibration phenomenon can also be suppressed.

The objective of this paper is to construct robust adaptive

controller T

m

such that:

O1: The measured load speed can be stabilized at a con-

stant value with performance constraints.

O2: All the state variables of the closed-loop system are

bounded.

Remark 1: For the rolling mill main drive system is

free of sensor errors, [22–26] investigated the torsional vi-

bration suppression control strategy without performance

constraints. However, in practice, there are always perfor-

mance constraint requirements for the load speed of the

main drive system, moreover, the measurement signals of-

ten have sensor errors. In this paper, we design the robust

adaptive control strategy for the main drive system with

unknown states sensor errors. The control strategy pro-

posed in this paper takes into account more practical con-

ditions, and based on the idea of performance constraints,

the performance of the load speed is limited to a predeter-

mined range.

3. MOTOR TORQUE DESIGN

In this section, we will propose the adaptive state feed-

back controller design for system (6) with sensor errors

and performance constraints. The performance constraints

transformation of load speed is proposed at first, and then

the memoryless adaptive state controller is designed.

3.1. Performance constraints transformation

In order to suppress torsional vibration, we define ˇz

1

=

ˇx

1

−x

d

, where x

d

is a constant that represents the steady

state load speed. Then from (6) and (7), the dynamic of ˇz

1

is that

.

ˇz

1

=λ

1

K

J

L

x

2

+

T

L

J

L

+

aPRe

c

(1−bRx

1

+

b

2

R

2

2

x

2

1

)−C

L

x

1

J

L

!

.

(8)

The transient and steady-state performances of ˇz

1

is pre-

served if the following inequality holds

−δ µ (t) < ˇz

1

<

¯

δ µ (t), (9)

where δ and

¯

δ are the chosen positive constants, µ (t) =

(µ (0)−µ (∞))e

−kt

+ µ (∞) with µ (0) > 0, µ (∞) > 0,k >

0.

We set ˇz

1

= µ (t) S (ε) and S (ε) =

¯

δ e

ε

−δ e

−ε

e

ε

+e

−ε

. Since the

function S(ε) is strictly monotonic increasing, its inverse

function exists as

ε = S

−1

ˇz

1

µ (t)

=

1

2

ln

s + δ

¯

δ −s

. (10)

For the controller design of the main drive system of

rolling mill, we design the following state transformation

z

1

= ε −

1

2

ln

δ

¯

δ

, (11)

and then the transformation state dynamic is

˙z

1

=

rλ

1

K

J

L

x

2

+

rλ

1

T

L

J

L

−r

ˇz

1

˙

µ (t)

µ (t)

,

4 Cheng Qian, Liuliu Zhang, and Changchun Hua

+ rλ

1

aPRe

c

(1 −bRx

1

+

b

2

R

2

2

x

2

1

) −C

L

x

1

J

L

, (12)

where r =

1

2µ

h

1

s+δ

−

1

s−

¯

δ

i

. Then if z

1

is proved to be

bounded, the performance constraints of the load speed

is guaranteed.

3.2. Motor torque design procedure

In this section, we will use the adaptive approxima-

tion method to deal with the unknown sensor errors.

With respect to the unknown parameters, define Θ =

max

n

λ

2

1

λ

2

2

,

1

λ

1

,λ

1

,

1

λ

2

1

,λ

2

1

,

λ

2

2

λ

2

3

,

λ

2

λ

1

,

λ

3

λ

2

o

, ρ

1

=

λ

2

λ

1

,ρ

2

=

λ

3

λ

2

,ρ

3

=

1

λ

3

. Let

ˆ

Θ and

ˆ

ρ

i

be the estimations of Θ and ρ

i

, respec-

tively, and the corresponding estimation errors are defined

as

˜

Θ = Θ−

ˆ

Θ and

˜

ρ

i

= ρ

i

−

ˆ

ρ

i

. The following lemmas play

very important role in the control design process.

Lemma 1 [37]: For any constant ε > 0 and any variable

z, the following relationship holds:

0 ≤

|

z

|

−

z

2

√

z

2

+ ε

2

≤ ε. (13)

Lemma 2 (Young’s inequality): For ∀(x,y) ∈ ℜ

2

, the

following inequality holds:

xy ≤

ε

p

p

|

x

|

p

+

1

qε

q

|

y

|

q

, (14)

where ε > 0, p > 1, q > 1 and (p −1) (q −1) = 1.

By using the dynamic surface control technique and

backstepping method, the design procedure for the main

drive system (6) consists of 3 steps, with the mo-

tor torque T

m

being deduced at the last step. First,

we introduce the following coordinate transformation

z

i+1

= ˇx

i+1

− v

i

, W

i+1

= v

i

− α

i

, where i = 1,2, α

i

and v

i

are the virtual controller and the filtered vir-

tual controller. Then, we define the compact sets Ω

i

=

n

∑

i

k=1

1

2

z

2

k

+

1

2

˜

Θ

2

+

∑

i−1

k=1

1

2

W

2

(k+1)

+

1

2

λ

1

λ

2

˜

ρ

2

1

≤ 2µ

o

, where

µ > 0 is a constant.

Step 1: To stabilize the first error transformation z

1

, the

first virtual controller α

1

and the adaptive law

.

ˆ

ρ

1

are pre-

sented as

α

1

= −

J

L

z

1

r

ˆ

ρ

2

1

¯

α

2

1

K

p

z

2

1

r

2

ˆ

ρ

2

1

¯

α

2

1

+ ε

2

12

, (15)

.

ˆ

ρ

1

= z

1

r

¯

α

1

−l

1

ˆ

ρ

1

, (16)

with

¯

α

1

is designed in (27), l

i

(i = 1,2,3) and ε

i j

(i =

1,2, 3, j = 1, 2) are designed positive parameters. Then,

in order to obtain the filter virtual control v

1

, let α

1

pass

through a first-order filter with constant τ

1

, we obtain

τ

1

˙v

1

+ v

1

= α

1

,α

1

(0) = v

1

(0). (17)

The dynamic of the boundary layer error W

2

is

˙

W

2

= −

W

2

τ

1

+ B

1

, (18)

where B

1

is the continuous function, which are obtained

based on the derivation of α

1

. Moreover, B

1

has maximum

¯

B

1

on the compact set Ω

1

.

Considering the first Lyapunov function

V

1

=

1

2

z

2

1

+

1

2

˜

Θ

2

+

1

2

λ

1

λ

2

˜

ρ

2

1

+

1

2

W

2

2

, (19)

the derivative of V

1

is

˙

V

1

=z

1

˙z

1

−

˜

Θ

.

ˆ

Θ −

λ

1

λ

2

˜

ρ

1

.

ˆ

ρ

1

+W

2

˙

W

2

=z

1

rλ

1

K

J

L

x

2

+

rλ

1

T

L

J

L

+ r

ˇz

1

˙

µ (t)

µ (t)

−z

1

rλ

1

aPRe

c

(1 −bRx

1

+

b

2

R

2

2

x

2

1

) −C

L

x

1

J

L

−

˜

Θ

.

ˆ

Θ −

λ

1

λ

2

˜

ρ

1

.

ˆ

ρ

1

+W

2

−

W

2

τ

1

+ B

1

=z

1

rλ

1

K

J

L

λ

2

(z

2

+ α

1

+W

2

) + z

1

rλ

1

T

L

J

L

−z

1

r

abe

c

PR

2

−C

L

J

L

ˇx

1

−z

1

r

ˇz

1

˙

µ (t)

µ (t)

−

˜

Θ

.

ˆ

Θ

+ z

1

r

aPRe

c

(λ

1

+

b

2

R

2

2

1

λ

2

1

ˇx

3

1

)

J

L

−

λ

1

λ

2

˜

ρ

1

.

ˆ

ρ

1

+W

2

−

W

2

τ

1

+ B

1

. (20)

By using Lemma 2, one has

z

1

r

Kλ

1

J

L

λ

2

(z

2

+W

2

) ≤a

11

K

J

L

2

Θz

2

1

r

2

+

1

2a

11

z

2

2

+

1

2a

11

W

2

2

, (21)

z

1

rλ

1

T

L

J

L

≤

a

12

2

¯

T

L

J

L

2

Θz

2

1

r

2

+

1

2a

12

, (22)

z

1

r

aPRe

c

(λ

1

+

b

2

R

2

2

1

λ

2

1

ˇx

3

1

)

J

L

≤

|

z

1

r

|

aPRe

c

J

L

(1 +

b

2

R

2

2

ˇx

3

1

)Θ

≤ ε

11

Θ +

z

2

1

r

2

aPRe

c

J

L

(1 +

b

2

R

2

2

ˇx

3

1

)

2

r

z

2

1

r

2

aPRe

c

J

L

(1 +

b

2

R

2

2

ˇx

3

1

)

2

+ ε

2

11

Θ,

(23)

W

2

B

1

≤

a

13

2

¯

B

2

1

W

2

2

+

1

2a

13

, (24)

where a

i j

(i, j = 1, 2,3) are designed positive parameters.

With Lemma 1 and (15), we can obtain

z

1

r

Kλ

1

J

L

λ

2

α

1

= −

z

2

1

r

2

ˆ

ρ

2

1

¯

α

2

1

p

z

2

1

r

2

ˆ

ρ

2

1

¯

α

2

1

+ ε

2

12

λ

1

λ

2

Adaptive Torsional Vibration Control of the Nonlinear Rolling Mill Main Drive System with Performance ... 5

≤ ε

12

λ

1

λ

2

−z

1

r

ˆ

ρ

1

¯

α

1

λ

1

λ

2

. (25)

Substituting (21)-(25) into (20) gives

˙

V

1

≤

1

2a

11

z

2

2

+ ε

11

Θ + ε

12

λ

1

λ

2

+

1

2a

12

+

1

2a

13

+ z

1

r

abe

c

PR

2

−C

L

J

L

ˇx

1

−z

1

r

ˇz

1

˙

µ (t)

µ (t)

−z

1

r

ˆ

ρ

1

¯

α

1

λ

1

λ

2

−z

1

r

˜

ρ

1

¯

α

1

λ

1

λ

2

+ l

1

λ

1

λ

2

ˆ

ρ

1

˜

ρ

1

+ z

1

rΘN

1

−

˜

Θ

.

ˆ

Θ +

−

1

τ

1

+

a

13

2

¯

B

2

1

+

1

2a

11

W

2

2

,

(26)

where N

1

= a

11

K

J

L

2

z

1

r +

z

1

r

aPRe

c

J

L

(1+

b

2

R

2

2

|

ˇx

3

1

|

)

2

r

z

2

1

r

2

aPRe

c

J

L

(1+

b

2

R

2

2

|

ˇx

3

1

|

)

2

+ε

2

11

+

a

12

2

¯

T

L

J

L

2

z

1

r.

From the definition of

˜

ρ

i

, −z

1

r

ˆ

ρ

1

¯

α

1

λ

1

λ

2

−z

1

r

˜

ρ

1

¯

α

1

λ

1

λ

2

=

−z

1

rρ

1

¯

α

1

λ

1

λ

2

= −z

1

r

¯

α

1

is satisfied. Then, choose

¯

α

1

=

ˆ

ΘN

1

−

ˇz

1

˙

µ (t)

µ (t)

+

abe

c

PR

2

−C

L

J

L

ˇx

1

+

h

1

z

1

r

, (27)

and with

l

1

λ

1

λ

2

ˆ

ρ

1

˜

ρ

1

≤ −

l

1

2

λ

1

λ

2

˜

ρ

2

1

+

l

1

2

λ

1

λ

2

ρ

2

1

, (28)

finally, we get

˙

V

1

≤−h

1

z

2

1

−τ

∗

1

W

2

2

−

l

1

2

λ

1

λ

2

˜

ρ

2

1

+

1

2a

11

z

2

2

+ O

1

−

˜

Θ

.

ˆ

Θ + τ

0

ˆ

Θ −z

1

rN

1

+ τ

0

˜

Θ

ˆ

Θ, (29)

where τ

0

is a positive designed constant, τ

∗

1

=

1

τ

1

−

a

13

2

¯

B

2

1

−

1

2a

11

, O

1

= ε

11

Θ + ε

12

λ

1

λ

2

+

1

2a

12

+

1

2a

13

+

l

1

2

λ

1

λ

2

ρ

2

1

.

Step 2: The second transformation for the main drive

system z

2

= ˇx

2

−v

1

will be considered. The derivative of

z

2

along (6) and (7) is that

˙z

2

=

λ

2

λ

3

ˇx

3

−

λ

2

λ

1

ˇx

1

− ˙v

1

. (30)

The second virtual control law α

2

and the adaptive law

.

ˆ

ρ

2

are proposed as

α

2

= −

z

2

ˆ

ρ

2

2

¯

α

2

2

p

z

2

2

ˆ

ρ

2

2

¯

α

2

2

+ ε

2

22

, (31)

.

ˆ

ρ

2

= z

2

¯

α

2

−l

2

ˆ

ρ

2

, (32)

where

¯

α

2

is designed later. Similarly, let α

2

pass through

a first-order filter v

2

with constant τ

2

to obtain v

2

,

τ

2

˙v

2

+ v

2

= α

2

, α

2

(0) = v

2

(0), (33)

and then the dynamic of the boundary layer error W

3

is

˙

W

3

= −

W

3

τ

2

+ B

2

, (34)

where B

2

has maximum

¯

B

2

on the compact set Ω

2

.

Similar to Step 1, we choose the second Lyapunov func-

tion as

V

2

= V

1

+

1

2

z

2

2

+

1

2

λ

2

λ

3

˜

ρ

2

2

+

1

2

W

2

3

, (35)

and take the time derivative of V

2

along (30) and (35)

yields

˙

V

2

≤−h

1

z

2

1

−τ

∗

1

W

2

2

−

l

1

2

λ

1

λ

2

˜

ρ

2

1

+

1

2a

11

z

2

2

+ O

1

−

˜

Θ

.

ˆ

Θ + τ

0

ˆ

Θ −z

1

rN

1

+ τ

0

˜

Θ

ˆ

Θ −

λ

2

λ

3

˜

ρ

2

.

ˆ

ρ

2

+ z

2

λ

2

λ

3

(z

3

+ α

2

+W

3

) −

λ

2

λ

1

ˇx

1

− ˙v

1

+W

3

˙

W

3

.

(36)

With Lemma 1 and Lemma 2, the following inequalities

hold,

z

2

λ

2

λ

3

(z

3

+W

3

) ≤ a

21

Θz

2

2

+

1

2a

21

z

2

3

+

1

2a

21

W

2

3

, (37)

−z

2

λ

2

λ

1

ˇx

1

≤ ε

21

Θ +

z

2

2

ˇx

2

1

p

z

2

2

ˇx

2

1

+ ε

2

21

Θ, (38)

λ

2

λ

3

z

2

α

2

= −

z

2

2

ˆ

ρ

2

2

¯

α

2

2

p

z

2

2

ˆ

ρ

2

2

¯

α

2

2

+ ε

2

22

λ

2

λ

3

≤ ε

22

λ

2

λ

3

−z

2

ˆ

ρ

2

¯

α

2

λ

2

λ

3

, (39)

W

3

B

2

≤

a

22

2

¯

B

2

2

W

2

3

+

1

2a

22

, (40)

l

2

λ

2

λ

3

ˆ

ρ

2

˜

ρ

2

≤ −

l

2

2

λ

2

λ

3

˜

ρ

2

2

+

l

2

2

λ

2

λ

3

ρ

2

2

. (41)

By choosing

¯

α

2

= h

2

z

2

− ˙v

1

+ N

2

ˆ

Θ +

1

2a

11

z

2

with N

2

=

a

21

z

2

+

z

2

ˇx

2

1

√

z

2

2

ˇx

2

1

+ε

2

21

, one can obtain

˙

V

2

≤

1

2a

21

z

2

3

−h

1

z

2

1

−h

2

z

2

2

−

l

1

2

λ

1

λ

2

˜

ρ

2

1

−

l

2

2

λ

2

λ

3

˜

ρ

2

2

−τ

∗

1

W

2

2

−τ

∗

2

W

2

3

−

˜

Θ

.

ˆ

Θ + τ

0

ˆ

Θ −z

1

rN

1

−z

2

N

2

+ τ

0

˜

Θ

ˆ

Θ + O

2

, (42)

where τ

∗

2

=

1

τ

2

−

a

22

2

¯

B

2

2

−

1

2a

21

, O

2

= O

1

+ ε

21

Θ + ε

22

λ

2

λ

3

+

l

2

2

λ

2

λ

3

ρ

2

2

+

1

2a

22

.

Step 3: Consider the third error transformation as z

3

=

ˇx

3

−v

2

, then, the derivative of z

3

is that

˙z

3

=

λ

3

T

m

J

m

−

C

m

J

m

ˇx

3

−

K

J

m

λ

3

λ

2

ˇx

2

− ˙v

2

(43)

6 Cheng Qian, Liuliu Zhang, and Changchun Hua

The motor torque T

m

and the adaptive laws

.

ˆ

ρ

3

,

.

ˆ

Θ are de-

signed as

T

m

= −

J

m

z

3

ˆ

ρ

2

3

¯

α

2

3

p

z

2

3

ˆ

ρ

2

3

¯

α

2

3

+ ε

2

32

(44)

.

ˆ

ρ

3

= z

3

¯

α

3

−l

3

ˆ

ρ

3

(45)

.

ˆ

Θ = −τ

0

ˆ

Θ + z

1

rN

1

+ z

2

N

2

+ z

3

N

3

(46)

with N

3

=

K

2

J

2

m

z

3

ˇx

2

2

r

K

2

J

2

m

z

2

3

ˇx

2

2

+ε

2

31

and

¯

α

3

=

1

2a

21

z

3

−

C

m

J

m

ˇx

3

− ˙v

2

+N

3

ˆ

Θ+

h

3

z

3

.

Choose the whole Lyapunov function as

V

3

= V

2

+

1

2

z

2

3

+

1

2

λ

3

˜

ρ

2

3

. (47)

The time derivative of V

3

can be derived as

˙

V

3

≤

1

2a

21

z

2

3

−h

1

z

2

1

−h

2

z

2

2

−

l

1

2

λ

1

λ

2

˜

ρ

2

1

−

l

2

2

λ

2

λ

3

˜

ρ

2

2

−τ

∗

1

W

2

2

−τ

∗

2

W

2

3

−

˜

Θ

.

ˆ

Θ + τ

0

ˆ

Θ −z

1

rN

1

−z

2

N

2

+ z

3

λ

3

T

m

J

m

−

C

m

J

m

ˇx

3

−

K

J

m

λ

3

λ

2

ˇx

2

− ˙v

2

−λ

3

˜

ρ

3

.

ˆ

ρ

3

+ τ

0

˜

Θ

ˆ

Θ + O

2

. (48)

Considering the following inequalities also hold,

−z

3

K

J

m

λ

3

λ

2

ˇx

2

≤ ε

31

Θ +

K

2

J

2

m

z

2

3

ˇx

2

2

q

K

2

J

2

m

z

2

3

ˇx

2

2

+ ε

2

31

Θ, (49)

λ

3

T

m

z

3

J

m

≤ ε

32

λ

3

−λ

3

z

3

ˆ

ρ

3

¯

α

3

, (50)

with

l

3

λ

3

ˆ

ρ

3

˜

ρ

3

≤ −

l

3

2

λ

3

˜

ρ

2

3

+

l

3

2

λ

3

ρ

2

3

, (51)

τ

0

˜

Θ

ˆ

Θ ≤ −

τ

0

2

˜

Θ

2

+

τ

0

2

Θ

2

, (52)

we have

˙

V

3

≤−h

1

z

2

1

−h

2

z

2

2

−h

3

z

2

3

−

l

1

2

λ

1

λ

2

˜

ρ

2

1

−

l

2

2

λ

2

λ

3

˜

ρ

2

2

−

l

3

2

λ

3

˜

ρ

2

3

−τ

∗

1

W

2

2

−τ

∗

2

W

2

3

−

τ

0

2

˜

Θ

2

+ O

3

≤−νV

3

+ O

3

, (53)

where O

3

= O

2

+

l

3

2

λ

3

ρ

2

3

+

τ

0

2

Θ

2

+ ε

31

Θ + ε

32

λ

3

, ν =

min{2h

1

, 2h

2

, 2h

3

, l

1

, l

2

, l

3

, 2τ

∗

1

, 2τ

∗

2

, τ

0

}.

Let ν > O

3

/µ, then

˙

V

3

< 0 on V

3

= µ. Thus, V

3

≤ µ is

an invariant set, that is, if V

3

(0) ≤ µ, then V

3

(t) ≤ µ for

all t > 0. Inequality (53) implies that V

3

(t) ≤V

3

(0)e

−νt

+

O

3

ν

(1 −e

−νt

). Then, we can obtain that as t → ∞,z

i

≤

q

2O

3

ν

,W

i

≤

q

2O

3

ν

. With the above analysis, we present

the main results of this paper as follows:

Theorem 1: Considering the main drive system of

rolling mill expressed by (1) with the unknown measure-

ment sensitivities, the dynamic controllers (15), (31) and

(44) with adaptive laws (16), (32), (45), (46) render the

load speed to a stable value with transient and steady-state

performance constraints and all signals in the main drive

system are semi-globally uniformly ultimately bounded.

Remark 2: From the definition of parameter O

3

follow-

ing (53), we can know that it contains many items. How-

ever, we add some adjustable parameters τ

0

, τ

1

, τ

2

, a

i j

,

l

i

, ε

i, j

and h

i

in the derivation of the Lyapunov function.

Here, parameters τ

1

, τ

2

and h

i

are all positive constants

and should be selected big enough, while parameters τ

0

,

l

i

, ε

i, j

and a

i, j

are positive constants and should be small

enough such that the residual set can be arbitrarily small

to obtain the better control performance. Moreover, we

consider the performance constraints control in this paper

and the load speed would be guaranteed into a designer-

specified region even with larger O

3

.

Remark 3: From (21)-(23), (25), (37)-(39), and (49)-

(50), we can observe that many unknown parameters are

located in different locations caused by unknown sensor

errors, which significantly enlarges the system under con-

sideration. In this paper, instead of directly estimating the

multiple unknown parameters, we estimate the bound of

them. Moreover, with the aid of dynamic surface tech-

niques, the control design procedure is simplified with

very few adaptive laws and the “explosion of complexity”

caused by backstepping technique can be avoided.

4. SIMULATION EXAMPLE

In order to verify the effectiveness of the algorithm pro-

posed in this paper, the No. 5 stand of the 2030 mm tan-

dem cold rolling mill was selected as the simulation ob-

ject, and the corresponding main drive system equipment

parameters are as follows: T

L

= 14500 N·m, J

m

= 1552

kg·m

2

, J

L

= 1542 kg·m

2

, K = 5.93 ×10

6

N·m/rad, C

m

=

2 × 10

5

N/(m/s), C

L

= 2 × 10

6

N/(m/s), P = 7807 kN,

R = 0.4 m, a = 0.13, b = 0.002, c = 0.2.

The performance constraints function is selected as

−5e

−5t

−0.5 < ˇz

1

< 2.5e

−5t

+ 0.5. The control laws and

the adaptive laws are selected as (15)-(16), (31)-(32), (44)-

(46) with x

d

= 20, a

i j

= 10 (i, j = 1, 2, 3), l

i

= 1 (i = 1,

2, 3), τ

0

= 1, τ

1

= τ

2

= 500, ε

i j

= 0.01 (i = 1, 2, 3, j = 1,

2), h

i

= 100 (i = 1, 2, 3). The sensor errors are chosen as

λ

1

= 0.8, λ

2

= 0.7, λ

3

= 0.9. The initial values are selected

as [x

1

, x

2

, x

3

,

ˆ

ρ

1

,

ˆ

ρ

2

,

ˆ

ρ

3

, v

1

, v

2

,

ˆ

Θ] = [25, 20, 20, 0, 0, 0, 0,

0, 0].

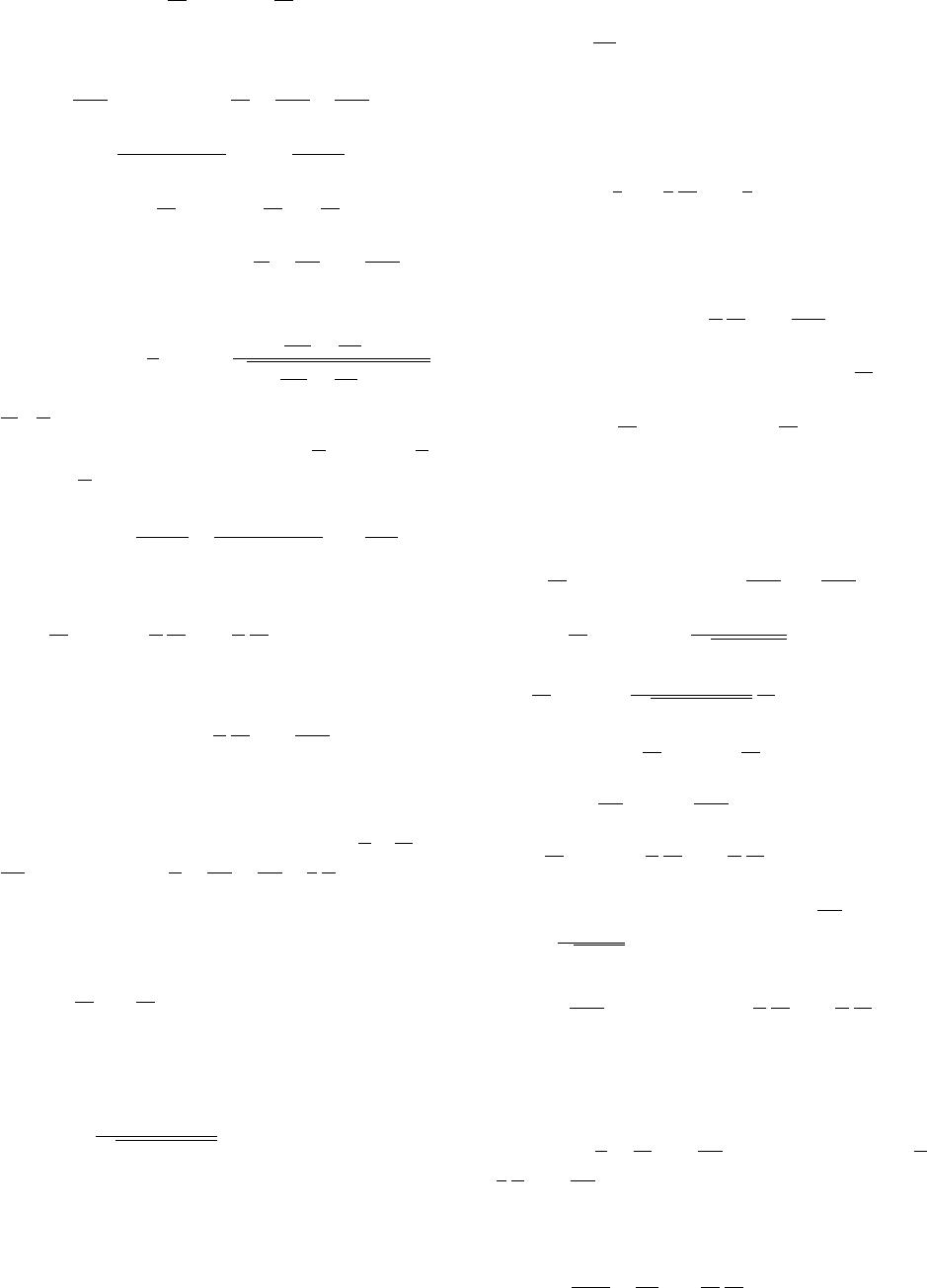

The simulation results are shown in Figs. 3-6. From

Fig. 3, we can see that the requirements of load speed

with performance constraints can be achieved. To validate

Adaptive Torsional Vibration Control of the Nonlinear Rolling Mill Main Drive System with Performance ... 7

Time s

0 0.5 1 1.5 2 2.5 3

Error of measurement load speed m/s

-6

-4

-2

0

2

4

Error with performance constraint

Lower bound

Upper bound

Error without performance constraint

Fig. 3. Tracking error of measurement load speed and the

performance constraints.

Time s

0 0.5 1 1.5 2 2.5 3

-600

-500

-400

-300

-200

-100

0

100

200

300

x(1)

x(2)

x(3)

Fig. 4. The state responses of the main drive system.

the improved performance with the proposed schemes, the

tracking error of load speed under the control of conven-

tional backstepping algorithm without prescribed perfor-

mance in the same parameter selection is also plotted in

Fig. 3. It can be observed that the convergence speed,

steady-state error and overshoot can be further reduced

to the preset range with the proposed schemes, and then,

the transient-state and steady-state performances are en-

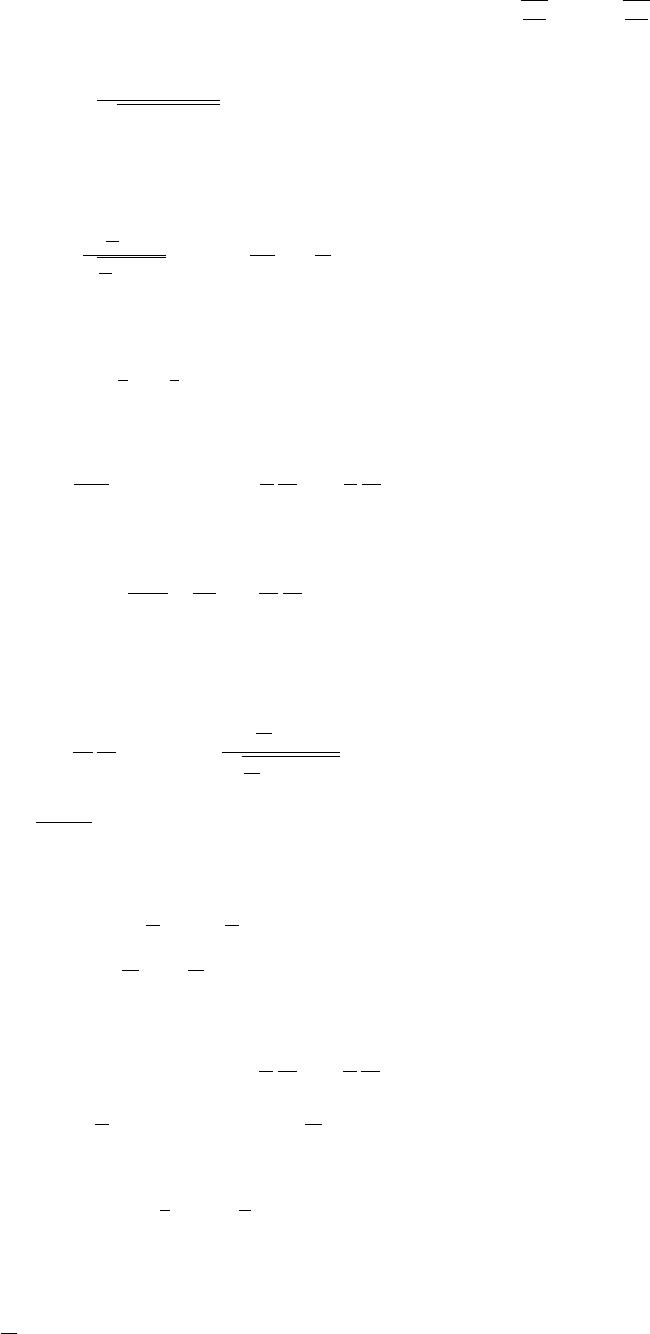

hanced. Fig. 4 shows the state variables of the closed-loop

system, from which we can see that they are all bounded.

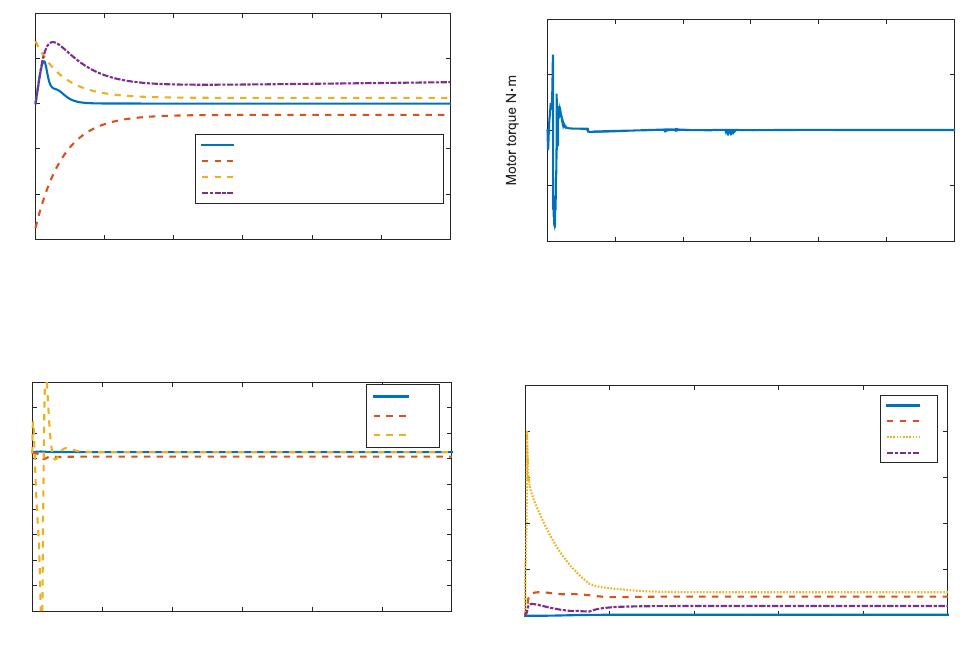

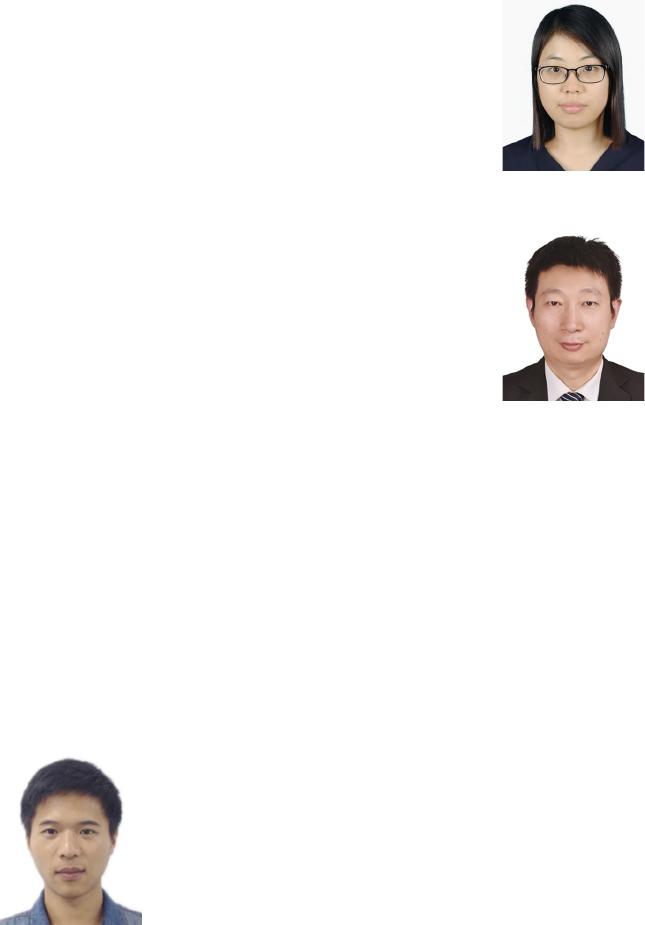

The motor torque and the adaptive laws are shown in

Fig. 5 and Fig. 6.

5. CONCLUSION

This paper established the torsional vibration mathe-

matical model and studied the torsional vibration suppres-

sion control problem of the main drive system of rolling

mill. The unknown measurement sensitivities in state vari-

ables caused by sensors are considered. With the help of

the performance constraints control, main drive system

torsional vibration controller is designed via backstepping

method and dynamic surface technology. The simulation

results show its effective performance on torsional vibra-

tion suppression.

Time s

0 0.5 1 1.5 2 2.5 3

×10

7

-1

-0.5

0

0.5

1

Fig. 5. The motor torque response.

Time s

0 2 4 6 8 10

0

2

4

6

8

10

ρ

1

ρ

2

ρ

3

Θ

Fig. 6. The adaptive law of the main drive system.

REFERENCES

[1] J. L. Chen, Z. G. Wang, J. Pan, Y. Y. Zi, Y. Wang, B.

Q. Chen, H. L. Sun, J. Yuan, and Z. J. He, “Customized

maximal-overlap multiwavelet denoising with data-driven

group threshold for condition monitoring of rolling mill

drivetrain,” Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing,

vol. 68-69, pp. 44-67, February 2016.

[2] L. Liu, N. Shao, S. Y. Ding, and Y. M. Fang, “Command

filter-based backstepping control for the speed and ten-

sion system of the reversible cold strip rolling mill using

disturbance observers,” International Journal of Control

Automation and Systems, 2019. DOI:10.1007/s12555-018-

0697-2

[3] P. Belli, S. Bittanti, and A. de Marco, “On the origin

of torsional vibrations in hot rolling mills and a possible

remedy,” Journal of Dynamic Systems Measurement and

Control-Transactions of the ASME, vol. 126, no. 4, pp. 811-

823, December 2004.

[4] K. Fujita and T. Saito, “Unstable vibration of roller mills,”

Journal of Sound and Vibration, vol. 297, no. 1-2, pp. 329-

350, October 2006.

[5] S. Liu, X. Li, Y. Q. Li, and H. B. Li, “Stability and bifur-

cation for a coupled nonlinear relative rotation system with

multi-time delay feedbacks,” Nonlinear Dynamics, vol. 77,

no. 3, pp. 923-934, August 2014.

8 Cheng Qian, Liuliu Zhang, and Changchun Hua

[6] J. L. Sun, Y. Peng, H. M. Liu, and G. B. Jiang, “Vertical

vibration of moving strip in rolling process based on beam

theory,” Chinese Journal of Mechnical Engineering, vol.

22, no. 5, pp. 680-687, October 2009.

[7] A. Heidari, M. R. Forouzan, and M. R. Niroomand, “De-

velopment and evaluation of friction models for chatter

simulation in cold strip rolling,” International Journal of

Advanced Manufacturing Technology, vol. 96, no. 5-8, pp.

2055-2075, May 2018.

[8] M. Mosayebi, F. Zarrinkolah, and K. Farmanesh, “Calcu-

lation of stiffness parameters and vibration analysis of a

cold rolling mill stand,” International Journal of Advanced

Manufacturing Technology, vol. 91, no. 9-12, pp. 4359-

4369, August 2017.

[9] X. B. Fan, Y. Zang, Y. K. Sun, and P. A. Wang, “Impact

analysis of roller system stability for four-high mill hori-

zontal vibration,” Shock and Vibration, A.N. 5693584, pp.

1-10, 2016.

[10] Y. Kim, C. W. Kim, S. Lee, and H. Park, “Dynamic model-

ing and numerical analysis of a cold rolling mill,” Interna-

tional Journal of Precision Engineering and Manufactur-

ing, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 407-413, March 2013.

[11] Q. Y. Wang, Z. Y. Jiang, J. W. Zhao, and M. Fang, “Multi-

factor coupling system characteristic of the dynamic roll

gap in the high-speed rolling mill during the unsteady lu-

brication process,” Tribology International, vol. 67, pp.

174-181, November 2013.

[12] X. Yang and C. N. Tong, “Coupling dynamic model and

control of chatter in cold rolling,” Journal of Dynamic Sys-

tems Measurement and Control-Transactions of the ASME,

vol. 134, no. 4, pp. 041001-1-8, July 2012.

[13] S. Liu, S. S. Zhao, B. Niu, J. X. Li, and H. B. Li, “Sta-

bility analysis of a nonlinear electromechanical coupling

transmission system with time delay feedback,” Nonlinear

Dynamics, vol. 86, no. 3, pp. 1863-1874, November 2016.

[14] L. Q. Zeng, Y. Zang, Z. Y. Gao, K. Liu, and X. C. Liu, “ Sta-

bility analysis of the rolling mill multiple-modal-coupling

vibration under nonlinear friction,” Journal of Vibroengi-

neering, vol. 17, no. 6, pp. 2824-2836, September 2015.

[15] H. Y. Zhao and K. F. Ehmann, “Stability analysis of chatter

in tandem rolling mills-part 1: Single-and multi-stand neg-

ative damping effect,” Journal of Manufacturing Science

and Engineering-Transactions of the ASME, vol. 135, no.

3, pp. 031001-1-7, June 2013.

[16] X. Lu, J. Sun, G. T. Li, Q. L. Wang, and D. H. Zhang,

“Dynamic analysis of vibration stability in tandem cold

rolling mill,” Journal of Materials Processing Technology,

vol. 272, pp. 47-57, October 2019.

[17] S. P. He, H. Y. Fang, M. G. Zhang, F. Liu, X. L. Luan, and

Z. D. Ding, “Online policy iterative-based H

∞

optimization

algorithm for a class of nonlinear systems,” Information

Science, vol. 495, pp. 1-13, August 2019.

[18] X. H. Chang and G. H. Yang, “New results on output feed-

back H

∞

control for linear discrete-time systems,” IEEE

Trans. Automatic Control, vol. 59, no. 5, pp. 1355-1359,

May 2014.

[19] X. H. Chang, C. Yang, and J. Xiong, “Quantized fuzzy

output feedback H

∞

control for nonlinear system with ad-

justment of dynamic parameters,” IEEE Trans. on Systems,

Man, and Cybernetics: Systems, vol. 49, no. 10, pp. 2005-

2015, October 2019.

[20] S. P. He, H. Y. Fang, M. G. Zhang, F. Liu, and Z. D. Ding,

“Adaptive optimal control for a class of nonlinear systems:

the online policy iteration appraoch,” IEEE Trans. on Neu-

ral Networks and Learning Systems, vol. 31, no. 2, pp. 549-

558, February 2020.

[21] L. Ma, X. Huo, X. D. Zhao, and G. D. Zong, “Adaptive

fuzzy tracking control for a class of uncertain switched

nonlinear systems with multiple constraints: a small gain

approach,” International Journal of Fuzzy Systems, vol. 21,

no. 8, pp. 2609-2624, November 2019.

[22] X. Yang, K. X. Peng, and C. N. Tong, “Robust backstep-

ping control for cold rolling main drive system with non-

linear uncertainties,” Abstract and Applied Analysis, A.N.

387890, pp. 1-7, 2013.

[23] R. C. Zhang and C. N. Tong, “Torsional vibration control

of the main drive system of a rolling mill based on an ex-

tended state observer and linear quadratic control,” Jour-

nal of Vibration and Control, vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 313-327,

March 2006.

[24] K. Fujikawa, Z. Q. Yang, H. Kobayashi, and T. Koga,

“Robust and fast speed control for torsional system based

on state-space method,” Proc. of the Inter. Conf. Indus-

trial Electronics, Control and Instrumentation, pp. 687-

692, 1991.

[25] Y. A. Amer, A. T. El-Sayed, and F. T. El-Bahrawy, “Tor-

sional vibration reduction for rolling mill’s main drive sys-

tem via negative velocity feedback under parametric ex-

citation,” Journal of Mechanical Science and Technology,

vol. 29, no. 4, pp. 1581-1589, April 2015.

[26] R. Dhaouadi, K. Kubo, and M. Tobise, “Two-degree-

of-freedom robust speed controller for high-performance

rolling mill drives,” IEEE Trans. Industry Applications,

vol. 29, no. 5, pp. 919-926, October 1993.

[27] C. P. Bechlioulis and G. A. Rovithakis, “Robust adap-

tive control of feedback linearizable MIMO nonlinear sys-

tems with prescribed performance,” IEEE Trans. Automatic

Control, vol. 53, no. 9, pp. 2090-2099, October 2008.

[28] C. C. Hua, L. L. Zhang, and X. P. Guan, “Decentralized

output feedback adaptive NN tracking control for time-

delay stochastic nonlinear systems with prescribed perfor-

mance,” IEEE Trans. Neural Networks and Learning Sys-

tems, vol. 26, no. 11, pp. 2749-2759, November 2015.

[29] R. Chang, Y. M. Fang, L. Liu, and K. S. Kang, “Pre-

scribed performance adaptive neural tracking control for

strict-feedback Markovian jump nonlinear systems with

time-varying delay,” International Journal of Control, Au-

tomation, and Systems, vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 1020-1031, June

2017.

[30] B. W. Chen and L. G. Tan, “Adaptive anti-saturation track-

ing control with prescribed performance for hypersonic ve-

hicle,” International Journal of Control, Automation, and

Systems, vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 394-404, February 2020.

Adaptive Torsional Vibration Control of the Nonlinear Rolling Mill Main Drive System with Performance ... 9

[31] Z. Y. Guan, Y. P. Ma, Z. W. Zheng, and N. Guo, “Prescribed

performance control for automatic carrier landing with dis-

turbance,” Nonlinear Dynamics, vol. 94, no. 2, pp. 1335-

1349, June 2018.

[32] S. I. Han and J. M. Lee, “Prescribed performance fuzzy

backstepping control for nonlinear large-scale systems,”

International Journal of Control, Automation, and Systems,

vol. 13, no. 6, pp. 1508-1520, September 2015.

[33] L. Ma, X. Huo, X. D. Zhao, and G. D. Zong,

“Observer-based adaptive neural tracking control for

output-constrained switched MIMO nonstrict-feedback

nonlinear systems with unknown dead zone,” Nonlinear

Dynamics, vol. 99, no. 2, pp. 1019-1036, January 2020.

[34] X. Zhang and W. Lin, “A K-filter-based adaptive control for

nonlinear systems with unknown parameters in state and

output equations,” Automatica, vol. 105, pp. 186-197, July

2019.

[35] S. Y. Oh and H. L. Choi, “A further result on global

stabilization of a class of nonlinear systems by output

feedback with unknown measurement sensitivity,” Interna-

tional Journal of Control, Automation, and Systems, vol.

17, no. 10, pp. 2500-2507, October 2019.

[36] Z. Y. Sun, C. Y. Liu, S. F. Su, and W. Sun, “Robust sta-

bilization of high-order nonlinear systems with unknown

sensitivities and applications in humanoid robot manipula-

tion,” IEEE Trans. Systems Man and Cybernetics: Systems,

2019. DOI:10.1109/TSMC.2019.2931768

[37] C. L. Wang and Y. Lin, “Decentralized adaptive tracking

control for a class of interconnected nonlinear time-varying

systems,” Automatica, vol. 54, pp. 16-24, April 2015.

Cheng Qian received his B.S. degree

in mechanical engineering from Yanshan

University, Qinhuangdao, China, in 2014.

He is currently working toward a Ph.D.

degree in electrical engineering from Yan-

shan University. His research interests are

in dynamic modeling, analysis and control

of rolling process.

Liuliu Zhang received her B.S. and Ph.D.

degree in electrical engineering from Yan-

shan University, Qinhuangdao, China, in

2012 and 2018, respectively. She is cur-

rently a Lecturer with Electrical Engineer-

ing, Yanshan University, China. Her re-

search interests include nonlinear control,

constraint control and adaptive control.

Changchun Hua received his Ph.D. de-

gree in electrical engineering from Yan-

shan University, Qinhuangdao, China, in

2005. He was a research Fellow in Na-

tional University of Singapore from 2006

to 2007. From 2007 to 2009, he worked

in Carleton University, Canada, funded by

Province of Ontario Ministry of Research

and Innovation Program. From 2009 to

2011, he worked in University of Duisburg-Essen, Germany,

funded by Alexander von Humboldt Foundation. Now he is a

full Professor in Yanshan University, China. He is the author

or coauthor of more than 110 papers in mathematical, technical

journals, and conferences. He has been involved in more than

10 projects supported by the National Natural Science Founda-

tion of China, the National Education Committee Foundation of

China, and other important foundations. His research interests

are in nonlinear control systems, control systems design over

network, teleoperation systems and intelligent control.

Publisher’s Note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard

to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affil-

iations.