Effect of Gas Composition on Nitriding and Wear Behavior

of Nitrided Titanium Alloy Ti-15V-3Cr-3Al-3Sn

C. Anandan, P.Dilli Babu, and L. Mohan

(Submitted November 8, 2012; in revised form December 26, 2012; published online April 6, 2013)

Titanium alloy, Ti-15V-3Cr-3Al-3Sn was nitrided at different temperatures with low pressure plasma with

100% nitrogen, and nitrogen diluted with hydrogen and argon. The nitrided layers were characterized for

hardness, structure, and composition. Nitrided samples show weight gain that depended on temperature

and duration of nitriding. EDS results show that intake of nitrogen is significant at temperatures above

750 °C. Hydrogen dilution increases intake of nitrogen. Samples nitrided with hydrogen dilution have

lower surface roughness and higher nitrogen concentration. Depth profiling by XPS shows the formation of

nitride in the near-surface region and also that nitrogen concentration in the interior of the nitrided layers is

higher at higher temperatures. Micro Raman shows that formation of nitride takes place at higher tem-

peratures. XRD shows that the nitrided layers consist predominantly of alpha Ti and Ti

2

N. This is reflected

in the hardness increase and hardness profile in the nitrided samples. The low intake of nitrogen by the

alloy is attributed to the low solubility of nitrogen in beta alloy and low diffusion coefficient of nitrogen.

Reciprocating wear studies showed a lower coefficient of friction and lower wear loss for nitrided samples

compared to that of substrate.

Keywords gas dilution, hardness, plasma nitriding, Ti-15-3,

titanium alloy, wear, XPS

1. Introduction

Titanium and its alloys have high strength-to-weight ratio

and possess excellent corrosion resistance. Pure Titanium is an

a alloy, and the a-to-b transformation occurs at about 885 C.

Depending on the nature of alloying elements and their

concentration, titanium alloys can exist in a, b,ora + b form,

and the transformation temperature may be higher or lower than

pure titanium (Ref 1). In case of a + b alloy, Ti-6Al-4V, the

a-to-b transformation occurs at 980 C. On the other hand, beta

alloys are a class of alloys for which the transus temperature

can be as low as 750 C (Ref 1, 2). Most of the metal-forming

operations of the titanium alloys are performed at high

temperatures because of the high temperatures needed for

inducing plastic flow. However, these high temperatures are

energy intensive. Also these thermomechanical treatments may

induce unwarranted metallurgical changes in the base material.

The low beta transus temperature of titanium alloys make them

amenable to lower-temperature operations compared with

a + b alloys. Among the several b alloys, vanadium-containing

alloys such as Ti-10-2-3 and Ti-15-3—find prominent place in

aerospace sector. For example, Ti-10-2-3 has been used in

landing gear application in aircraft and Ti-15-3 has found

several applications in aerospace industry (Ref 2).

While titanium alloys possess high strength-to-weight ratio

and good corrosion resistance, they suffer from poor wear

resistance. They are prone to severe galling and scouring in the

presence of moving contacts (Ref 3, 4). Therefore, usage of

titanium alloys is mainly restricted to components under static

loading conditions in many industries, mainly in aerospace and

chemical industries (Ref 2, 3, 5). For applications that require

wear resistance, therefore, it is necessary to increase the surface

hardness of these alloys (Ref 5-7). Surface modifications by ion

implantation, (Ref 4, 8-11) nitriding, (Ref 11-13), and duplex

treatments (Ref 6, 7) have been carried out on titanium alloys.

The nitriding behaviors of pure titanium and the most popular

titanium alloy Ti-6Al-4V have been well documented (Ref 11,

14-17). These studies show that effective nitriding takes place

at temperatures close to the beta transus temperatures. Since the

beta transus temperature of beta alloys is low, it is expected that

effective nitriding of these alloys can be carried out at lower

temperatures. However, in the case of beta alloys, only limited

reports are available on their nitriding behavior. Of these, the

study by Zhecheva et al. is notable (Ref 18-20). Those

experiments were carried out in gas phase in the temperature

range of 800-1050 C and at pressures of few Pascals. Their

main observation has been that the extent to which beta alloys

can be nitrided is limited. For example, their investigations of

Ti-10-2-3 and LCB have shown that the nitride-layer thick-

nesses in these alloy are low, and hardness increase is also low

(Ref 20).

The present article reports the results of a detailed inves-

tigation on nitriding of the beta alloy Ti-15V-3Cr-3Al-3Sn

(Ti-15-3)—in a low-pressure nitrogen plasma in the temperature

range of 600-900 C instead of gas nitriding. The results show

that the alloyÕs nitridability is low and higher temperatures, i.e.,

>800 C, as in the case of Ti-6Al-4V, are needed to effectively

nitride these alloys. Also, effects of hydrogen and argon dilution

of nitrogen on nitriding of the alloy are discussed.

C. Anandan, P. Dilli Babu, and L. Mohan, Surface Engineering

Division, CSIR—National Aerospace Laboratories, P.O. Box 1779,

Old Airport Road, Bangalore 560 017 Karnataka, India. Contact

e-mail: [email protected].

JMEPEG (2013) 22:2623–2633 ASM International

DOI: 10.1007/s11665-013-0540-0 1059-9495/$19.00

Journal of Materials Engineering and Performance Volume 22(9) September 2013—2623

2. Materials and Methods

Titanium alloy, Ti-15-3, was procured in the form of 2-mm-

thick sheets from M/s. Titanium Metal Corporation, USA. The

composition of the material is 15V, 2.98Cr, 3.12Al, 3.05Sn,

0.15Fe and the balance Ti. The beta transus temperature is in

the range of 750-775 C. Flat samples of dimensions

25 9 25 9 2mm

3

, size were used for nitriding experiments.

These samples were prepared for plasma nitriding by grinding

with silicon carbide sheets of grit sizes varying from 400 to

1200 and polished with 0.3 lm alumina. Finally, they were

ultrasonically cleaned with acetone for 10 minutes and weighed

using a Sartorius balance before loading into the vacuum

chamber. The roughness of the samples after polishing was

0.07 lm. The vacuum chamber was evacuated to a pressure of

less than 4 9 10

6

mbar, and the samples were heated to the

required temperature on a heating stage. Plasma nitriding was

carried out at 600, 700, 750, 800, 850, and 900 C with

atmospheres of 100% N, 80% N-20% H, and 80% N-20% Ar.

Plasma was generated using 13.56-MHz RF generator at 50 W.

The details of the temperature and duration of the experiments

are given in Table 1. After nitriding, the samples were cooled to

room temperature under vacuum and analyzed for change in

weight, roughness, hardness, and composition.

The nitrided samples were weighed after treatment. The

surface hardness values of the nitrided samples were measured

using the Buehler

Micromet Testing Machine with KnoopsÕ

indenter at loads of 25, 50, 100, and 200 gf. The substrate

hardness is in the range of 350-360 HK at 50-gf load. The cross-

sectional hardness profile of the samples was measured at 50-gf

load after molding them in resin mould and polishing. The

cross-sectional optical micrographs of the nitrided edge were

obtained after etching the polished samples using KrollÕs reagent

(25 mL H

2

O + 2 mL conc. HNO

3

+ 1 mL conc. HF) for 15 s.

The roughness of the samples was measured using Mitutoyo

surface profiler. The presence of various phases in the nitrided

layer was identified by means of X-Ray diffraction (XRD) using

PHILIPS X-ray diffractometer (BRUKER, Germany). A mono-

chromatic source, Cu K

a

radiation (k = 0.1548 nm), was used,

Table 1 Plasma-nitriding temperatures and durations for

different gas compositions

Temperature (°C)

Duration in hours

100% N 80:20 (N:H) 80:20 (N:Ar)

700 4 4 …

700 8 8 …

750 4 4 …

750 8 8 …

800 4 4 4

800 8 8 8

850 4 4 …

850 8 8 …

900 8 4 …

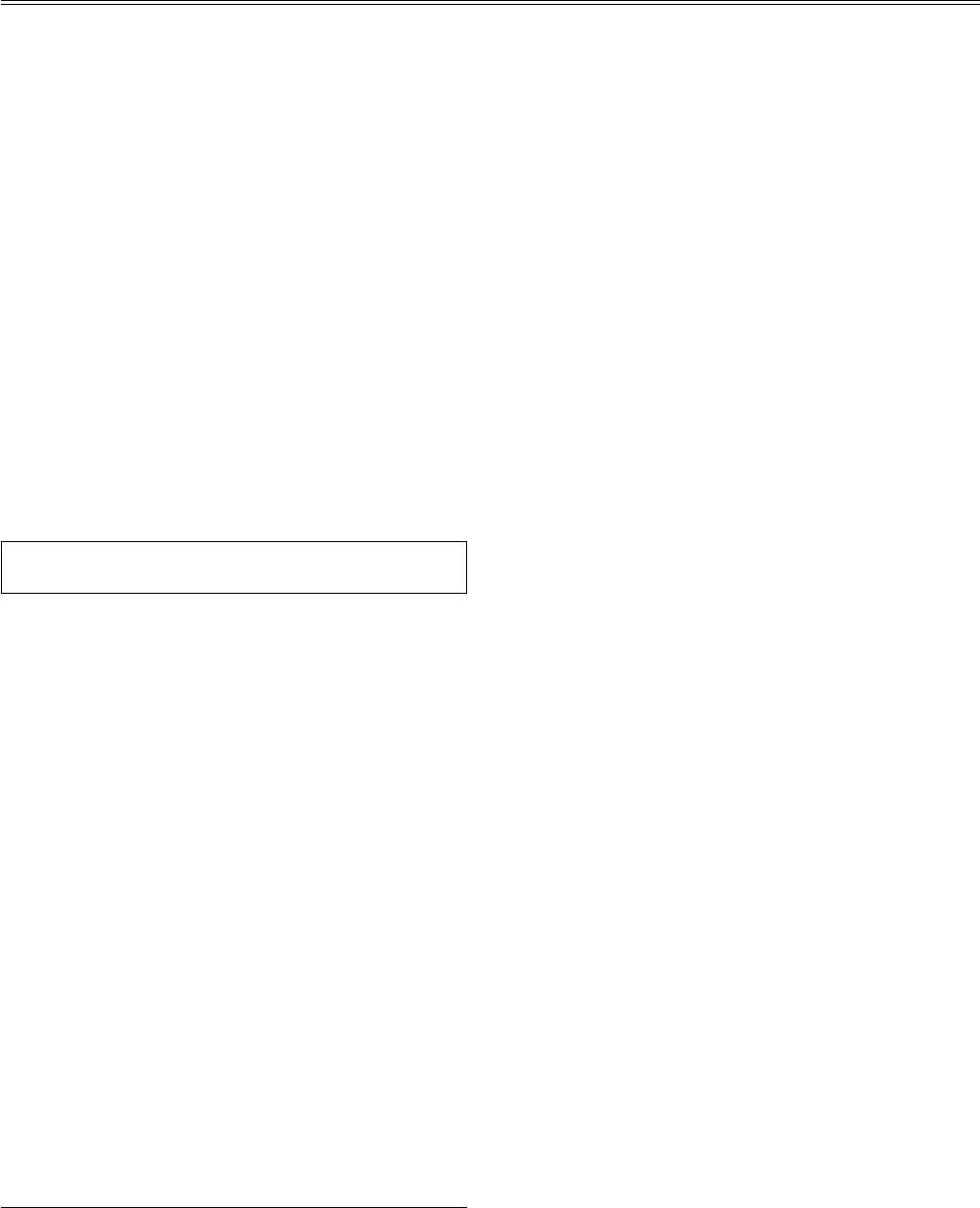

Fig. 1 Surface Hardness of samples nitrided for 4 h at different

temperatures with different gas compositions: (a) 100% nitrogen,

(b) 20% hydrogen-diluted nitrogen and argon-diluted nitrogen

Fig. 2 Variation of hardness with nitriding time for different gas

compositions: (a) 100% N and (b) 80% N-20% H and 80% N-20%

Ar

2624—Volume 22(9) September 2013 Journal of Materials Engineering and Performance

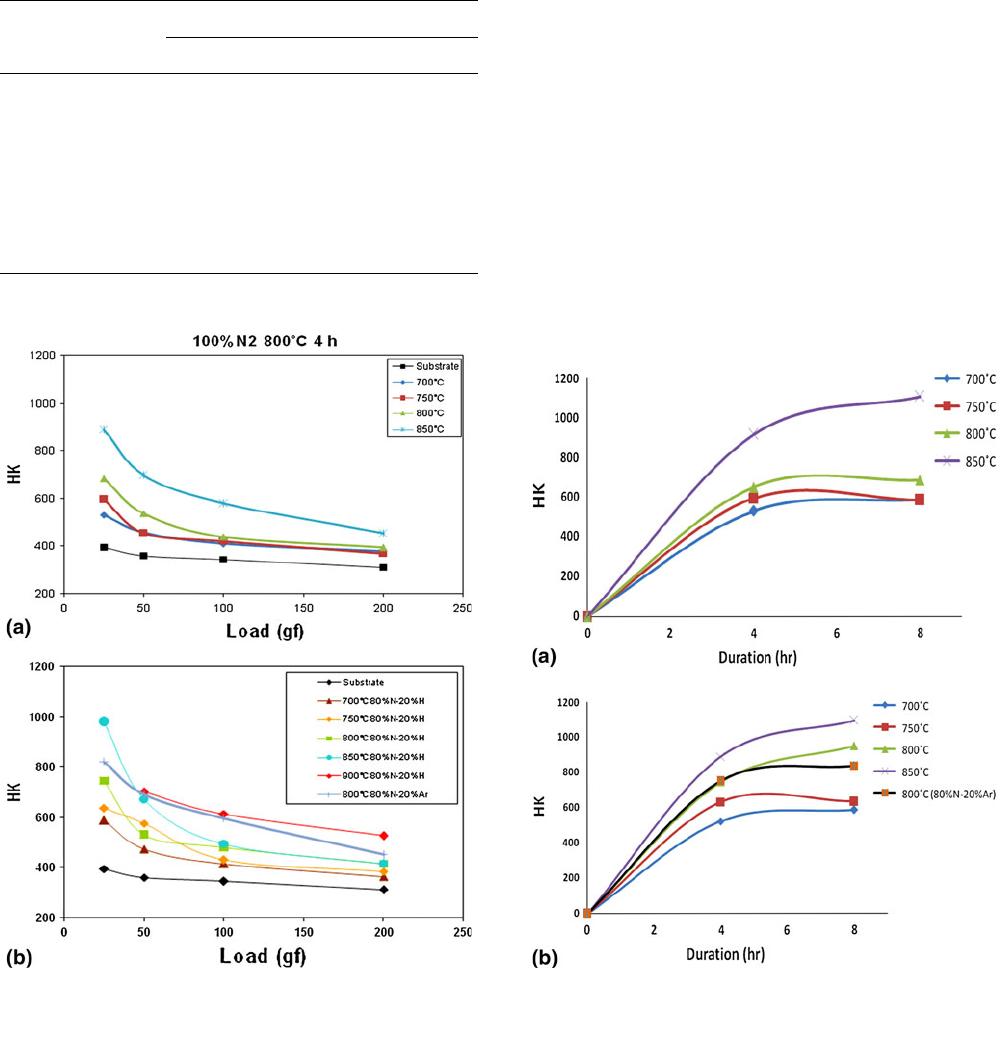

Fig. 3 Cross-sectional hardness for samples nitrided at different temperature and gas compositions: (a) 100% N and (b) 80% N-20% H and

80% N-20 % Ar

Fig. 4 Cross-sectional optical micrographs of samples nitrided at different gas compositions: (a) 8 h/800 C in 100% N, (b) 4 h/800 C in 80%

N-20% H, and (c) 4 h/800 C in 80% N-20% Ar (5009)

Journal of Materials Engineering and Performance Volume 22(9) September 2013—2625

and the samples were scanned from 0 to 80 at a scanning rate

of 0.5/min. Micro Raman spectra were obtained using Labram

010 Model of DILOR-JOBIN-YVON-SPEX Micro Raman

spectrometer with 623.4-nm laser. The surface morphologies of

the samples were examined through Carl Zeiss Supra 40 VP

FESEM. The composition of the nitrided layer was obtained

using Inca Penta Fetx3 (Oxford) EDAX analyzer attached to the

FESEM and also by means of X-ray Photoelectron Spectros-

copy (XPS). The XPS spectra were obtained on a SPECS XPS

system equipped with a hemispherical analyzer and a single-

channel detector, and twin anode X-ray source. Core level

spectra of Ti2p and N1s were obtained using 100-W Al K

a

radiation at a pass energy of 25 eV. The spectra were obtained in

the as-received condition, and after sputter etching with argon

ions. Elemental distribution in the nitrided layer was obtained by

sputter profiling using 1 keV argon ions at a pressure of

1 9 10

5

mbar and recording the spectra after each sputtering.

Wear studies were carried out on a reciprocating-type wear tester

(Model CM 9084 DuCom) (Ref 21). An alumina ball of 6-mm

diameter was used as the counter surface. A stroke length of

10 mm and a frequency of 100 Hz/min were used at 3 and 5N

normal forces. The duration of experiment was 20 min. After

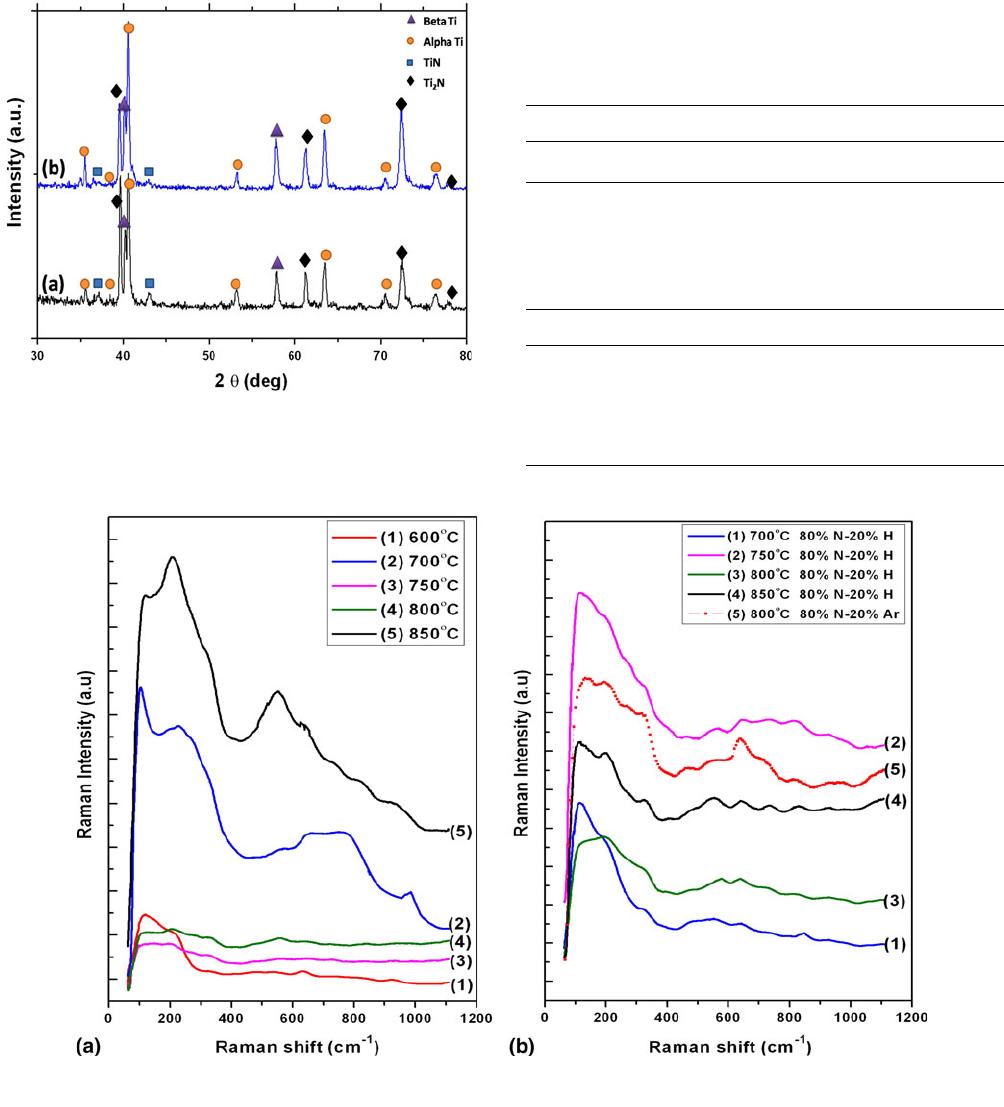

Fig. 6 Raman spectra of samples treated at different temperatures for 8 h (a) 100% N and (b) 80% N-20% H and 80% N-20% Ar

Table 3 Comparison of N at.% after nitriding for 8 h

with different gas compositions

Temperature (°C) Gas composition N (at.%)

750 100% N 17.92

750 80% N-20% H 20.25

800 100% N 18.13

800 80% N-20% H 24.26

800 80% N-20% Ar 17.68

Table 2 Nitrogen concentration in at.% in samples

nitrided in 100% N for 8 h

Temperature (°C) 600 700 750 800 850

N (at.%) 2.56 12.99 17.92 18.13 33.77

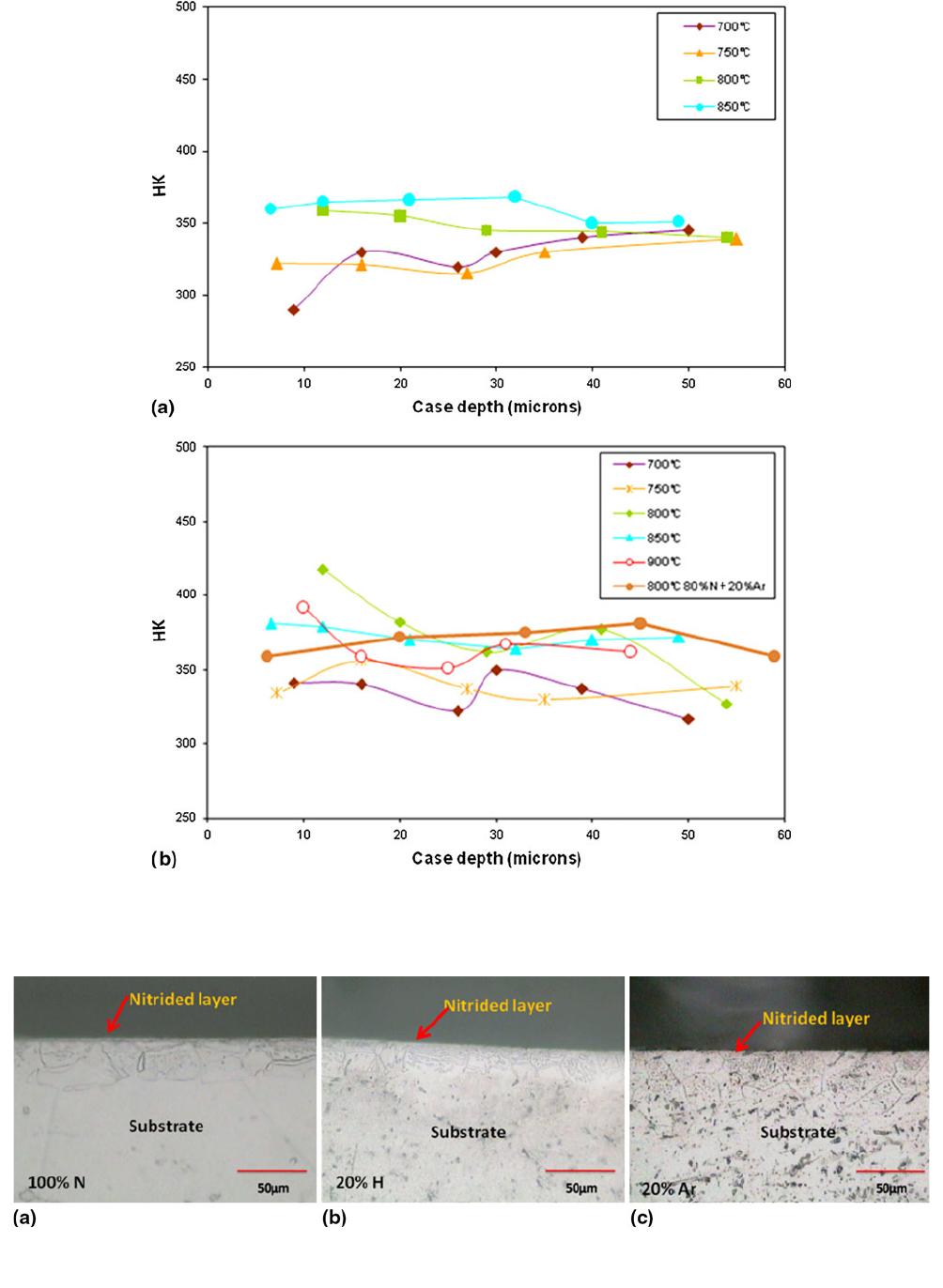

Fig. 5 X-ray diffraction pattern for (a) sample nitride at 850 C for

4 h in 100% nitrogen, and (b) sample nitride at 800 C for 4 h in

hydrogen-diluted nitrogen

2626—Volume 22(9) September 2013 Journal of Materials Engineering and Performance

the experiments, the samples were examined for wear profile

using 2D and 3D profilometer, Nanomap 500 LS.

3. Results and Discussion

The roughness of the substrate before nitriding was

0.07 lm. The roughness increased marginally to about

0.08 lm after nitriding in 100% nitrogen, especially at higher

temperatures. After nitriding with hydrogen dilution, the

roughness was 0.05 lm. There was marginal effect of temper-

ature in this case. With argon dilution, the roughness increased

slightly to 0.09 lm. With increasing duration of nitriding, the

roughness also increased in this case. All the nitrided samples

showed a weight gain. The weight gain depended on the

nitriding temperature, duration and gas composition. Significant

weight gain was observed only after nitriding at greater than

750 C. Dilution of nitrogen with hydrogen seems to increase

nitrogen intake by the sample.

The surface hardness of samples nitrided at different

temperatures for 4 h in 100% nitrogen and nitrogen diluted

with 20% hydrogen and 20% argon, are shown in Fig. 1(a) and

(b), respectively. It can be observed from the figures that the

hardness of the samples increases with temperature. The

hardness at 25 gf has increased by 2-3 times after nitriding at

higher temperatures. A comparison of the graphs shows that

increase in hardness is higher after nitriding with hydrogen-

diluted nitrogen compared with nitriding in 100% nitrogen- or

Ar-diluted nitrogen. Also, the decrease of hardness with load is

less steep in this case. Figure 2(a) and (b) shows the

dependence of hardness on nitriding duration at different

temperatures. The graphs show that the hardness increases with

time, but significant increase is again found only after nitriding

at greater than 750 C.

Hardness profiles are shown in Fig. 3(a) and (b) for samples

nitrided at different temperatures with different gas composi-

tions. The data were obtained at a load of 50 gf. As can be seen

in the graphs, hardness has not increased in the subsurface

region of the nitrided layers. The expected trend of a high

hardness at the surface that decreases with depth into the

substrate is not observed. The hardness remains almost

constant. Similar observations have been made by Sha and

Malinov (Ref 20) and Zhecheva et al. (Ref 17, 18) in their gas-

nitriding experiments on beta titanium alloys. Samples treated

under 80% N-20% H show a comparatively higher hardness up

to about 20 lm.

Optical micrographs of the cross section of the sample

nitrided at 800 C for 8 h using 100% nitrogen and samples

nitrided at 800 C for 4 h using hydrogen- and argon- diluted

nitrogen are given in Fig. 4(a)-(c), respectively. Very thin

nitrided layers can be seen in the figures, implying very thin

nitride-layer formation along with a-phase in the near-surface

region. The thin nitrided edge shows that the alloy is difficult to

nitride. This is further discussed later.

X-ray diffraction patterns from the samples nitrided at

850 C using 100% N and at 800 C using hydrogen diluted

nitrogen are given in Fig. 5(a) and (b). The location of different

peaks pertaining to (b) beta phase, (a) alpha phase, and nitrides,

TiN and Ti

2

N, are shown in the figures (Ref 20, 22, 23). After

nitriding, appearance of a phase can be seen along with the

nitrides. The intensity of the TiN phase is much lower than that

of Ti

2

N. This shows that predominantly Ti

2

N is formed along

with alpha-phase formation. In the sample nitrided with

hydrogen dilution, the intensities of the alpha and Ti

2

N peaks

are higher implying greater intake of nitrogen.

Figure 6(a) and (b) shows the micro Raman spectra of

samples nitrided at different temperatures using 100% nitrogen

and 20% hydrogen- and argon-diluted cases. For TiNx, the

transverse optical and longitudinal optical (TO + LO) phonon

peaks occur in the 500-800 cm

1

wave number range, which

correspond to titanium vacancies in the lattice. The transverse

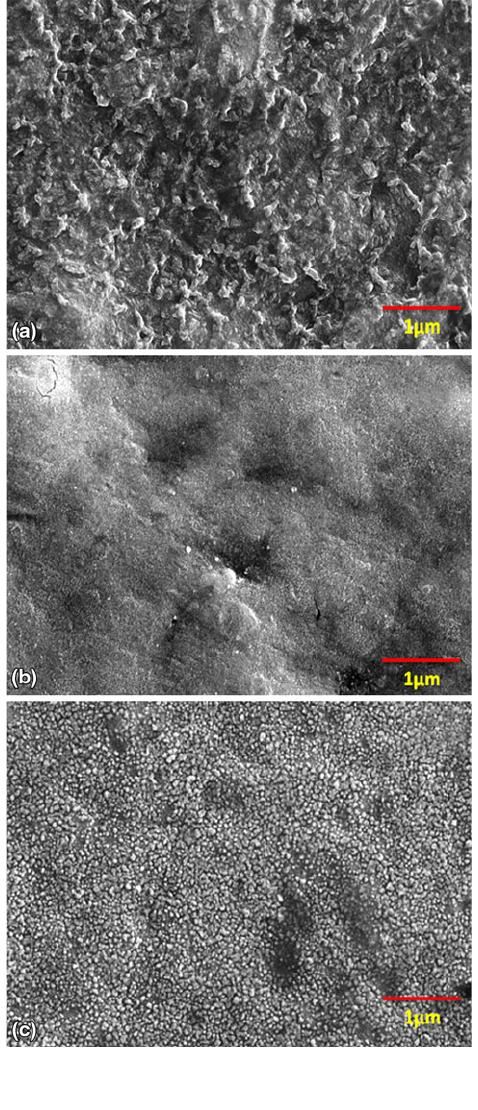

Fig. 7 FESEM images of samples nitride for 8 h at 800 C:

(a) 100% N, (b) 80% N-20% H, and (c) 80% N-20% Ar

Journal of Materials Engineering and Performance Volume 22(9) September 2013—2627

acoustic and longitudinal acoustic (TA + LA) phonons occur in

the 200-400 cm

1

wave number range, which correspond to

nitrogen vacancies in the lattice (Ref 24). As seen in the

spectra, significant intensities can be observed only after

800 C nitriding, and at lower temperatures, the intensities of

the peaks are low, especially in the 550-800 cm

1

wave

number range. For samples treated for 8 h in 100% N, Raman

peaks were observed in the wave number range of 210-

220 cm

1

, close to that of standard nitride TA/LA peaks. In the

case of samples nitrided with hydrogen dilution, the spectral

features do not resemble that of TiN, and at higher wave

number range of 500-800 cm

1

, peaks are not clear. The ratio

of the TO + LO phonon peak intensities to that of TA + LA

acoustic phonon intensities in TiN

x

has been used as a measure

of concentration of nitrogen vacancies in TiN

x

. If the intensity

ratio is lower than 1, then the nitrogen concentration, x, is lower

than unity (Ref 25-27). From a qualitative assessment of the

Raman spectra shown in Fig. 6(a) and (b), it is clear that x is

less than 1 in these samples. This shows that nitrogen intake by

the samples is lower than that needed for stoichiometric TiN

formation.

Table 2 shows the atomic percentage of nitrogen under

samples after 8 h of nitriding in 100% N at different

temperatures, and Table 3 compares the nitrogen concentrations

in samples nitrided for 8 h at 750 C and 800 C under 100%

N, 80% N-20% H, and 80% N-20% Ar gas compositions. It can

be observed from the above tables that significant increase in

nitrogen concentration can be observed only after nitriding at

greater than 750 C, and after nitriding at 850 C, nitrogen

concentration reaches 33.7 at.%. Further, it can be seen from

Table 3 that hydrogen dilution increases nitrogen concentration

in the nitrided layers, whereas argon dilution leads to a nominal

decrease. In stoichiometric TiN, the nitrogen concentration is

50 at.% and in Ti

2

N, it is 33.3 at.%. Therefore, as deduced

from Raman spectral intensities and X-ray diffraction data, the

nitrogen concentration is lower than that expected from the one

that is needed for TiN formation, and the EDS results shown in

Table 3 support is conclusion.

Fig. 8 Distribution of nitrogen (a) and titanium (b) in samples nitrided at different temperatures in 100% N (inset: XPS spectra of (a) N1s and

(b) Ti2p core levels obtained at different depths from samples nitrided for 4 h at 800 C)

2628—Volume 22(9) September 2013 Journal of Materials Engineering and Performance

FESEM images of the surface morphologies of the samples

nitrided at 800 C for 8 h are shown in Fig. 7(a)-(c) for various

gas compositions. It can be seen from the micrographs that in

the case of samples nitrided with 100% nitrogen, the surface

has ridge-like structure whereas that in argon the diluted-case

the surface appears rough with nanometer-sized precipitates

present on the surface. In the case of samples nitrided with

hydrogen-diluted nitrogen, the surface appears smoother. This

is in conformity with earlier results of surface roughness

measurements, where samples nitrided with hydrogen dilution

had lower surface roughness values.

Figure 8(a) and (b) shows nitrogen and titanium distribution

in the samples after nitriding in 100% nitrogen at different

temperatures. The insets in the figures show the Ti2p and N1s

core level spectra after sputter etching for different durations. In

the case of Ti2p core level spectra, oxide as well as nitride

peaks are present on the surface with Ti2p3/2 core level-

binding energies at 458 and 456 eV, respectively (Ref 28-30).

After etching for few minutes, the oxide is removed, and only

nitride is present. Further etching shifts the peak position to

lower binding energy values with increasing sputtering time. In

the case of N1s core level, the peak binding energy is at

398.5 eV, corresponding to nitrogen in nitride form and shifts

to lower BE values with sputter etching. After nitriding for 4 h

at 800 C, the surface nitrogen concentration is about 23 at.%

and decreases sharply with respect to sputtering time. After

nitriding for 2 h at 850 C the surface concentration is 17 at.%

and decreases with increasing sputter depth less steeply. After

nitriding at 900 C for 1 h, the surface concentration is 15 at.%,

but its decreases very slowly with increasing sputter time. These

profiles show that at temperatures lower than 850 C, the

diffusion of nitrogen is low, and significant diffusion takes place

only at higher temperatures. This trend in diffusion is reflected

in the intake of nitrogen in the near-surface region and

consequent hardness increase and its profile that could be

achieved. The hardness profiles shown in Fig. 1(a) and (b)

shows that hardness decreases rapidly with load and also that the

hardness profile is nearly flat as shown in Fig. 2(a) and (b).

Since intake of nitrogen is low, alpha titanium is observed as

nitrogen is an alpha stabilizer, and Ti

2

N is the predominant

phase formed. Precipitates of TiN may be formed as evidenced

from the low intensity of TiN peaks in the XRD. As nitrogen

diffusion coefficient is low in titanium at temperatures lower

than 800 C, the nitrided layer thickness is also low.

0 5 10 15 20

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

Substrate

3N

5N

COF

Time (in mins)

(a)

0 5 10 15 20

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

COF

Time (in mins)

100% N

(b)

0 5 10 15 20

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

(c)

80% N-20%H

COF

Time (in mins)

0 5 10 15 20

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

(d)

Time (in mins)

COF

80% N-20%Ar

3N

5N

3N

5N

3N

5N

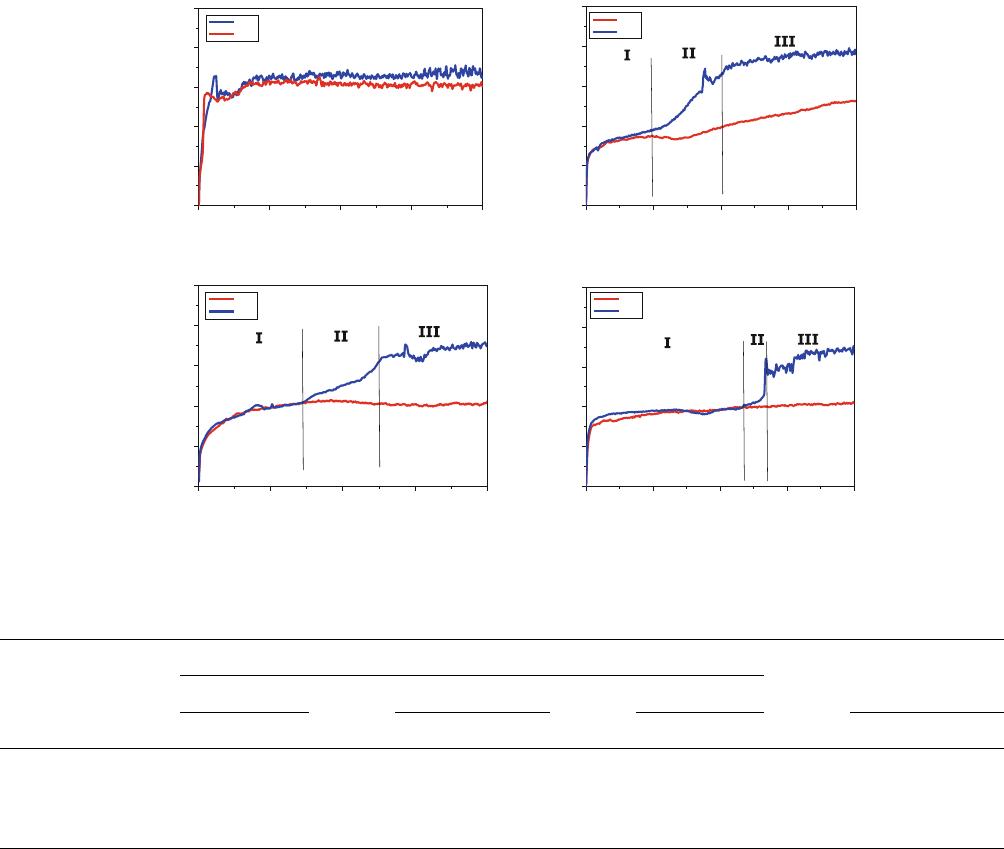

Fig. 9 COF versus time on (a) substrate and samples nitride at 800 C for 4 h, (b) 100% N, (c) 80% N-20% H, and (d) 80% N-20% Ar

Table 4 COF and wear loss for substrate and nitrided samples

Average COF under different loads

Wear loss (mm

3

)Region-I Region-II Region-III

3N 5N 3N 5N 3N 5N 3N 5N

Substrate 0.6 0.6 …………0.14 0.225

100% N 0.3 0.3 0.3 0.5-0.7 0.3 0.7 … 0.155

80-20% N-H 0.3 0.3 0.3 0.4-0.6 0.3 0.6 … 0.075

80-20% N-Ar 0.3 0.3 0.3 0.4-0.6 0.3 0.6 … 0.075

Journal of Materials Engineering and Performance Volume 22(9) September 2013—2629

The wear and frictional properties of the substrate and

samples nitrided at different conditions were investigated in a

linear reciprocating wear test. The evolutions of coefficient of

friction (COF) for different loads in the linear reciprocating

wear test are shown in Fig. 9(a)-(d). The average values of

COF and wear loss for the Ti-15-3 substrate and nitrided

samples are given in Table 4. While in the case of substrate the

COF increases rapidly to a high value of 0.6 at both 3N and 5N

loads, the nitrided samples behave differently. In these cases,

the COF is low at 3N load, especially for the samples nitrided

with diluted nitrogen; at 5N load, three regimes can be seen in

the figures in the evolution of the friction coefficient. In region-

I, the COF is low (0.3-0.4), and in region-III, it is close to that

of substrate with a transition in region-II. The COF increases

gradually in the transition region. Thus, nitriding considerably

reduces the friction at low loads, and at higher loads, once the

nitrided layer is removed, the COF reaches that of substrate.

Dilution of nitrogen with hydrogen or argon increases duration

of region-I, the low-COF region. Hydrogen dilution further

provides a gradual transition to region-III.

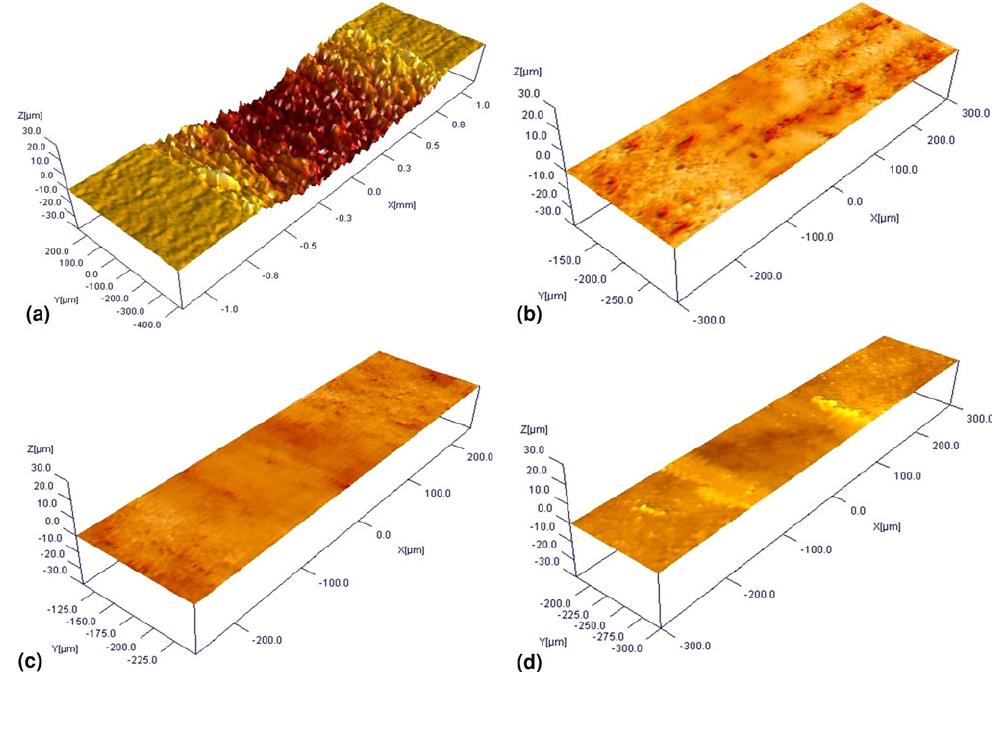

The 3D profiles of wear tracks on the substrate and nitrided

samples are shown in Fig. 10 for 3N load. In the case of

substrate, the profile shows clear wear profile, from which wear

loss can be estimated. For the nitrided samples, the wear profile

was smoother with no clear wear profile, suggesting negligible

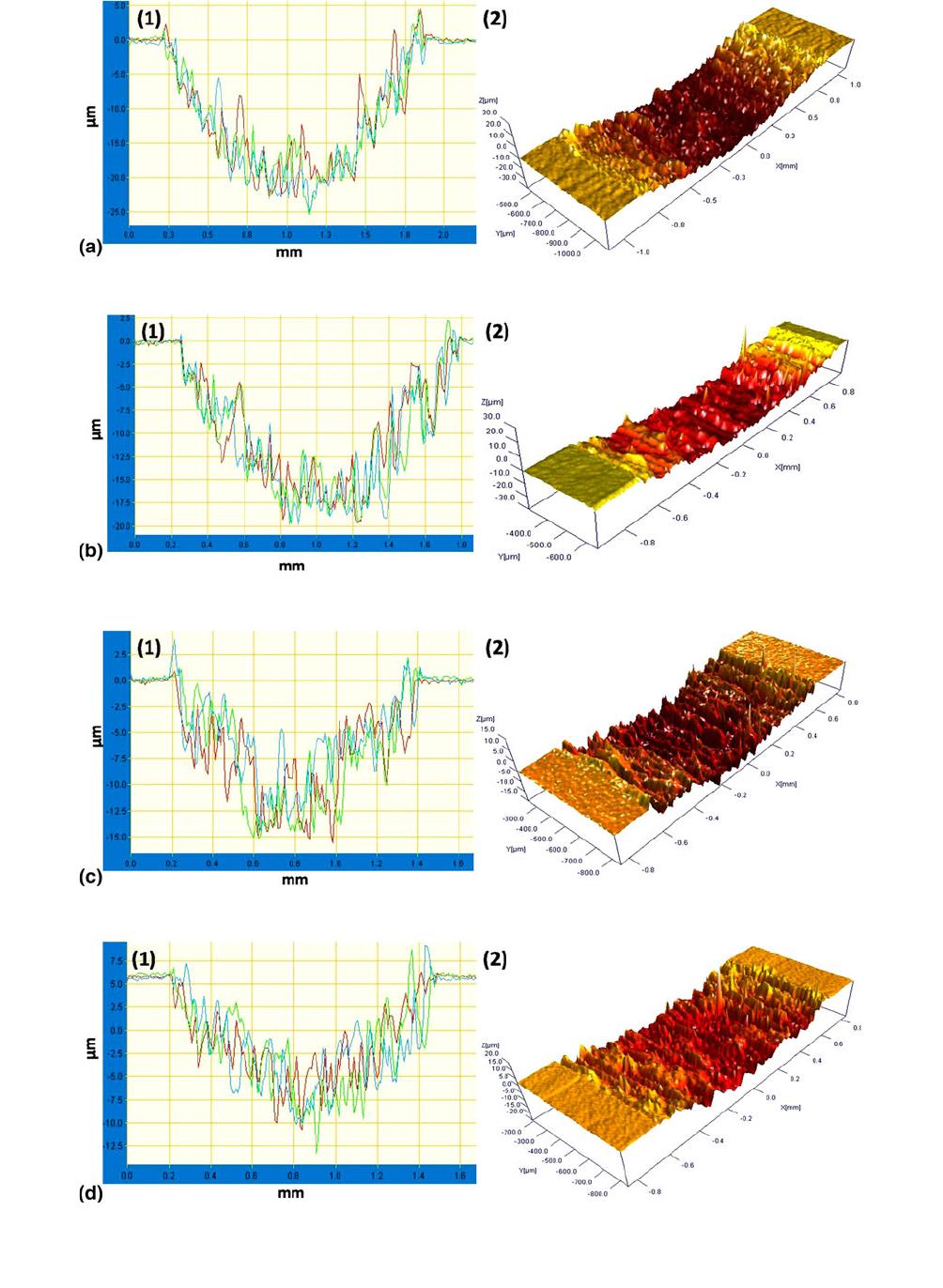

wear. The 2D and 3D wear profiles of the wear tracks at 5N

load are shown in Fig. 11(a) for the substrate and for nitrided

samples in Fig. 11(b)-(d). It can be seen from the 2D and 3D

profiles in Fig. 11(a) that the wear profile on the substrate has

deep grooves of several microns depth, while the wear tracks

on the nitrided samples appear less deep. The 2D wear

profiles of the samples at higher magnification are shown in

Fig. 11(a)-(d). The figs show that nitriding with dilution

decreases wear, as the wear tracks appear smoother than those

on the substrate and sample nitrided with 100% nitrogen. Wear

loss shown in Table 4 indicates that nitriding reduces the wear

loss. In the case of substrate, the wear loss nearly doubles to

0.225 mm

3

from 0.14 mm

3

for increase in load from 3N to 5N.

After nitriding, the wear is negligible for 3N load. For 5N load,

after nitriding with 100% N, wear loss is reduced by 50% to

0.15 mm

3

, while for samples nitrided with dilution of nitrogen

with H and Ar, it is further reduced to 0.07 mm

3

. Thus, the

appearance of deep grooves in wear tracks and the considerable

wear loss at 3N load itself suggest that the wear is abrasive in

nature in the case of substrate. In the case of nitrided samples,

the 3D wear profile is smoother, and wear loss is negligible at

3N load. The COF is also lower during the entire duration of

wear testing. At 5N load, the wear loss is lower than that of

substrate, and the COF is low in region-I. This shows that the

wear mechanism has changed from abrasive wear on the

substrate to adhesive wear after nitriding. At higher loads, once

the nitrided layer is removed, the wear mechanism changes to

abrasive wear as seen from the wear profile and higher COF at

the end of the wear test. Further, the transition from region-I to

III is gradual in the case of samples nitrided with hydrogen

dilution. Thus, nitriding with diluted nitrogen, especially with

Fig. 10 Profiles of wear tracks in 3D at 3N load on (a) substrate and samples nitrided at 800 C for 4 h, (b) 100% N, (c) 80% N-20% H, and

(d) 80% N-20% Ar

2630—Volume 22(9) September 2013 Journal of Materials Engineering and Performance

Fig. 11 (1) 2D and (2) 3D profiles of wear tracks at 5N load at high resolution on (a) substrate and samples nitrided at 800 C for 4 h,

(b) 100% N, (c) 80% N-20% H, and (d) 80% N-20% Ar

Journal of Materials Engineering and Performance Volume 22(9) September 2013—2631

hydrogen, improves the wear behavior of the titanium

alloy Ti-15-3 by reducing the COF and decreasing the wear

loss.

The above results on nitrided titanium alloy Ti-15-3 show that

the alloy has poor nitridability. Even though the beta transus

temperature of the alloy is low, i.e., 750-770 C, the alloy has to

be heated to temperatures >800 C for effective nitriding to take

place. This implies that irrespective of beta transus temperatures,

titanium alloys have to be heated to temperatures greater than

800 C for effective nitriding. Hydrogen dilution helps in

increasing the nitrogen intake as can be seen from the hardness

data and EDS results. It is known that hydrogen removes the

surface oxide by etching and also increases ionization of nitrogen

in the plasma. The removal of the oxide barrier and the

availability of more nitrogen ions and atoms due to increased

ionization increase the intake of nitrogen by the sample. Even

then, the nitriding kinetics is low at temperatures lower than

800 C. With argon dilution, the sample surface is sputtered

during the nitriding process, and also the partial pressure of

nitrogen is lowered. While sputtering removes the oxide as well

as nitrided layers, the reduced nitrogen partial pressure decreases

the intake of nitrogen and helps in controlling the composition of

nitrided layer. Analyses of the nitrided layers by EDS, micro

Raman, and XPS show that intake of nitrogen is lower at

temperatures lowers than 800 C. The lower intake of nitrogen

leads to the formation of a phase and predominantly Ti

2

N

formation, as seen in XRD. Depth profiling of the nitrided layers

by XPS shows that diffusion of nitrogen into the interior of the

sample is low. All these factors determine the hardness, the

hardness profile, and the wear behavior of the nitrided samples as

discussed above.

4. Conclusions

Beta titanium alloy, Ti-15V-3Cr-3Al-3Sn (Ti-15-3) was

plasma nitrided in low-pressure RF plasma using nitrogen

and nitrogen diluted with hydrogen and argon at tempera-

tures less than and greater than the beta transus temperature

of the material. The results show that effective nitriding of

the alloy can occur only at temperatures higher than the beta

transus temperature, and even then the intake of nitrogen is

low. XRD shows the formation of alpha phase, and

predominantly, Ti

2

N. Micro Raman spectra, EDS, and XPS

show that nitrogen concentration in the nitrided layer is low.

Depth profiling by XPS shows that nitrogen profile in the

material is shallow. This is reflected in the hardness and its

profile in the nitrided layers. Wear studies show a low COF

and lower wear loss for plasma-nitrided samples, especially

with hydrogen dilution.

Acknowledgments

The study was carried under the 11th five-year plan projects on

enhancement of knowledge base in aerospace materials project

SIP-SED-05 funded by CSIR-NAL. The authors would like to

thank Director, NAL for permission to publish this research; and

Head, SED for constant encouragement. The authors would like

to thank Mr. Siju, Mr. NT. Manikandanath, Mr. Praveen, and

Mr. Muniprakash for various characterizations.

References

1. R. Boyer, G. Welsch, and E.W. Collings, Materials Properties

Handbook: Titanium Alloys, ASM International, Materials Park, 2003

2. C. Leyens and M. Peters, Titanium and Titanium Alloys: Fundamentals

and Applications, Wiley-VCH, Germany, 2003

3. K.G. Budinski, Tribological Properties of Titanium Alloys, Wear,

1992, 151, p 203–217

4. S.M. Johns, T. Bell, M. Samandi, and G.A. Collins, Wear Resistance of

Plasma Immersion Ion Implanted Ti6A14V, Surf. Coat. Technol., 1996,

85, p 7–14

5. H. Dong and T. Bell, Designer Surfaces for Titanium Components, Ind.

Lubr. Tribol., 1998, 50(6), p 282–289

6. H. Dong and T. Bell, Ti-2003 Science and Technology, Proceedings of

the 10th World Conference on Titanium: Volume-II, G. Lutjering and

J. Albrecht, Eds., Wiley-VCH, Germany, 2004

7. X. Liu, P.K. Chu, and C. Ding, Surface Modification of Titanium,

Titanium Alloys, and Related Materials for Biomedical Applications,

Mater. Sci. Eng. R, 2004, 47, p 49–121

8. X. Qiu, J.R. Conrad, R.A. Dodd, and F.J. Worzala, Plasma Source

Nitrogen Ion Implantation of Ti-6Al-4V, Metall. Trans. A, 1990, 21A,

p 1663–1667

9. B.Y. Tang, P.K. Chu, S.Y. Wang, K.W. Chow, and X.F. Wang, Methane

and Nitrogen Plasma Immersion Ion Implantation of Titanium Metal,

Surf. Coat. Technol., 1998, 103-104, p 248–251

10. S.Y. Wang, P.K. Chu, B.Y. Tang, X.C. Zeng, Y.B. Chen, and X.F.

Wang, Radio Frequency Plasma Nitriding and Nitrogen Plasma

Immersion Ion Implantation of Ti6Al4V, Surf. Coat. Technol., 1997,

93, p 309–313

11. E.S. Metin and O.T. Inal, Microstructure and Microhardness Evalua-

tions in Ion Nitrided Titanium, Mater. Sci. Eng. A, 1991, 145, p 65–77

12. C. Lugmair, R. Kullmer, A. Gebeshuber, C. Mitterer, M. Stoiber, H.

Patrovsky, and M. Adley, Ti-2003 Science and Technology, Proceed-

ings of the 10

th

world conference on Titanium: Volume-II, G. Lutjering

and J. Albrecht, Eds., Wiley-VCH, Germany, 2004

13. U. Huchel and S. Stramke, Ti-2003 Science and Technology, Proceed-

ings of the 10th world conference on Titanium: Volume-II, G. Lutjering

and J. Albrecht, Eds., Wiley-VCH, Germany, 2004

14. K.N. Strafford and J.M. Towell, The Interaction of Titanium and

Titanium Alloys with Nitrogen at Elevated Temperatures. I. The

Kinetics and Mechanism of the Titanium-Nitrogen Reaction, Oxid.

Met., 1976, 10, p 41–67

15. K.N. Strafford and J.M. Towell, The Interaction of Titanium and

Titanium Alloys with Nitrogen at Elevated Temperatures. II. The

Nitridation Behaviour of Alloys Containing 5 wt.% Percent of

Aluminium and Chromium, Oxid. Met., 1976, 10, p 69–84

16. E. Metin and O.T. Inal, Kinetics of Layer Growth and Multiphase

Diffusion in Ion Nitrided Titanium, Metall. Trans. A, 1989, 20A,

p 1819–1832

17. N.R. McDonald and G.R. Wallwork, The Reaction of Nitrogen with

Titanium Between 800 and 1200C, Oxid. Met., 1970, 2-3, p 263–

283

18. A. Zhecheva, W. Sha, S. Malinov, and A. Long, Enhancing the

Microstructure and Properties of Titanium Alloys Through Nitriding

and Other Surface Engineering Methods, Surf. Coat. Technol., 2005,

200, p 2192–2220

19. A. Zhecheva, S. Malinov, and W. Sha, Titanium Alloys After Surface

Gas Nitriding, Surf. Coat. Technol., 2006, 201, p 247–2467

20. W. Sha and S. Malinov, Titanium Alloys: Modelling of Microstructure,

Properties and Applications, Woodhead Publishing Ltd., Cambridge,

2009

21. Prateek Kumar, P. Dilli Babu, L. Mohan, C. Anandan, and V.K.

William Grips, Wear and Corrosion Behavior of Zr-Doped DLC on

Ti-13Zr-13Nb Biomedical Alloy, J. Mater. Eng. Perform., 2012, doi:

10.1007/s11665-012-0230-3

22. S.L.R. da Silva, L.O. Kerber, L. Amaral, and C.A. dos Santos, X-Ray

Diffraction Measurements of Plasma Nitrided Ti6Al4V, Surf. Coat.

Technol., 1999, 116-119, p 342–346

23. F.M. El-Hossary, N.Z. Negm, S.M. Khalil, and M. Raaif, Surface

Modification of Titanium by Radio Frequency Plasma Nitriding, Thin

Solid films, 2006, 497, p 196–202

24. M.A.Z. Vasconcellos, R. Hinrichs, C.S. Javorsky, G. Giuriatti, and

J.A.T. Borges da Costa, Micro-Raman Characterization of Plasma

Nitrided Ti6Al4V-ELI, Surf. Coat. Technol., 2007, 202, p 275–279

2632—Volume 22(9) September 2013 Journal of Materials Engineering and Performance