Vol.:(0123456789)

Environment, Development and Sustainability

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-020-00993-7

1 3

Preservation ofhistorical heritage increases bird biodiversity

inurban centers

TulaciBhakti

1

· FernandaRossi

1

· PedrodeOliveiraMaa

1

·

EduardoFrancodeAlmeida

1

· MariaAugustaGonçalvesFujaco

2

·

CristianoSchetinideAzevedo

1

Received: 16 April 2020 / Accepted: 16 September 2020

© Springer Nature B.V. 2020

Abstract

Urban expansion negatively influences biodiversity by eliminating habitats and homoge-

nizing the biotic component, to which many species are unable to respond. However, his-

torical cities, with their protected heritage sites, maintain many fragments of vegetation

(gardens, squares, etc.). Such fragments permit the existence of biodiversity, especially of

birds, because they provide areas for shelter and food and function as stepping stones that

increases the permeability of the urban matrix. We hypothesized that the presence of green

areas, such as gardens and parks, would favor greater richness and abundance of bird spe-

cies, especially omnivores and granivores, during the dry season and in the Historic Center

of the city of Ouro Preto. Birds were sampled by point counts at 35 points distributed

throughout the urban matrix of Ouro Preto, where richness and abundance were recorded

and correlated with land use. Both the presence of green areas and the maintenance of the

Historic Center influenced the bird community present in the urban center, with higher

richness in areas with more shrubs and trees and closer to larger forested fragments. Bird

abundance was greater in the Historic Center and during the rainy season. These findings

demonstrate that maintaining heritage sites in urban centers can mitigate the expected neg-

ative impacts of urbanization by allowing small patches of vegetation to serve as favorable

habitats for bird species.

Keywords Avifauna· Abundance· Conservation· Historical center· Richness·

Urbanization

1 Introduction

Urbanization transforms both the physical and biotic structures of a given habitat and can

interfere with various ecological processes that involve local fauna and flora (Mendonça

and Anjos 2005). Such modifications result in a landscape composed of a mosaic of envi-

ronments, with floristic composition and structure usually different from those originally

* Cristiano Schetini de Azevedo

cristianorox[email protected]; cristiano.azevedo@ufop.edu.br

Extended author information available on the last page of the article

T.Bhakti et al.

1 3

present (Grimm etal. 2008; Patra etal. 2018). These mosaics are diffuse with patches of

native vegetation interspersed by areas with different levels of human occupation (Marzluff

etal. 2001; Yi etal. 2016).

Biodiversity can be directly or indirectly affected by urbanization (McDonald et al.

2019; Turrini etal. 2016). Direct effects are observed when a natural area is replaced by

an urban area with the construction of buildings, houses, or other human modifications

(Pejchar etal. 2015). All the changes that occur to biotic and abiotic conditions in a newly

urbanized environment, such as modifications to temperature, light, and wind (Beninde

etal. 2015; McDonald etal. 2013), as well as reductions in connectivity among vegetation

fragments and increased edge effects, are also considered direct effects of urbanization on

biodiversity (Concepción etal. 2015; Schneider etal. 2015; Veselkin etal. 2018). Pollu-

tion produced by urban areas and the resources needed for the correct functioning of the

city, like energy and food, are considered indirect impacts of urbanization on biodiversity

(McDonald etal. 2019; Turrini etal. 2016).

The effects of urbanization can be evaluated by the impacts on local biodiversity, such

as birds (Ikin etal. 2012; Ortega-Álvarez and MacGregor-Fors 2009). Birds are commonly

dependent on local environmental characteristics and are often used to measure the degree

of urbanization (Fontana etal. 2011; Møller etal. 2015; Ortega-Álvarez and MacGregor-

Fors 2009; Rodrigues etal. 2018). Birds are excellent models for studying the impacts of

urbanization and fragmentation because they are easily observed in cities, their taxonomy

is well defined and they present high species and functional richness and thus are consid-

ered good bioindicators for habitat quality (Anjos etal. 2015; Li Yong etal. 2011; Powell

etal. 2015). In this way, it is possible to use characteristics of species, such as food prefer-

ences, and characteristics of the urban landscape, such as the degree of urbanization and

the presence of vegetated areas, to assess how an urban center acts as a filter for bird spe-

cies (Ikin etal. 2012; Silva etal. 2016).

Different trophic guilds of birds can respond differently to urbanization (Cristaldi etal.

2017; Evans etal. 2011; Sol etal. 2014). Granivorous and omnivorous species are more

common in urban areas because they feed on food items that are abundant there (e.g., grass

seeds are common in cities) or have a more generalist diet and consume a wide range of the

available food items, including human-industrialized food wastes (Croci etal. 2008). More

specialized bird guilds, like frugivores and insectivores, are rarer in urban environments

because they normally occur in larger green areas that provide more food and specific habi-

tats (Cristaldi etal. 2017; Silva etal. 2016).

Urbanization can increase the abundance of several species, but it usually reduces total

richness (Chace and Walsh 2006). Due to the changes in conditions that urbanization of

environments brings, many species become extinct, which leads to biotic homogenization

(Blair 2008). On the other hand, there are indications that the maintenance of green areas

in cities, such as parks, squares and trees on public roads, favors the occurrence of bird

species in urban areas (Barth etal. 2015; Castro Pena etal. 2017). Even though they are

small, birds use these green areas as habitat or as stepping stones (small green areas used

as a resting place when traveling to larger green areas; Boscolo etal. 2008; Metzger 2001).

These small fragments can allow greater permeability of species into urban landscapes

(Baum etal. 2004; Bhakti etal. 2018; Fischer and Lindenmayer 2002), by making con-

nections with other fragments of vegetation located in peri-urban areas (Ikin etal. 2013;

Manhães and Loures-Ribeiro 2005).

Landscapes of cites are continuously changing, with new urban areas being added as cit-

ies grow (Farrell 2017). Green areas within cities also change, often being excluded from

the matrix after renovations (Mensah 2014). However, there are cities that are considered

Preservation ofhistorical heritage increases bird biodiversity…

1 3

historical heritage, whose green areas tend to remain in the urban matrix for longer periods

of time since no radical renovations are permitted (Rostami etal. 2015). Such a scenario

would allow the persistence of old green areas within urban areas, which could play a role

in the preservation of biodiversity by experiencing less anthropic disturbance (Ferreira

etal. 2013).

The maintenance of such older green areas has the potential to maintain greater biodi-

versity since their age has allowed sufficient time for plant–animal interactions to become

established, with bird communities being composed of less sensitive and more urban-

adapted species in these older green areas (Castro Pena etal. 2017; Eriksson 2016; Threl-

fall etal. 2017). Connectivity among fragments, as well their sizes and shapes, can permit

mobility and interchange of birds through the city matrix (Caneva etal. 2020; Parris etal.

2018). If fragments are closer to environmentally protected areas, they can increase the

permeability of a city for birds (Bhakti etal. 2018; Parris etal. 2018). Thus, greater rich-

ness and abundance of bird species are expected in green areas of historical heritage cities.

Bird communities can change seasonally due to the influences of weather and produc-

tivity (Seoane etal. 2013; Seress and Liker 2015). During the dry season, for example,

when food availability decreases, many migrant species leave an area in search of more

suitable places (Lepczyk etal. 2017; Leveau 2018). However, the environment of a city is

more homogeneous than natural environments, including less fluctuations in food availabil-

ity (Seress and Liker 2015; Tryjanowski etal. 2015). Thus, changes in bird communities

of cities are especially expected during the dry season because more bird species and indi-

viduals will seek resources within the urban matrix, thereby increasing bird richness and

abundance (Caula etal. 2008, 2014).

Thus, the present study aimed to evaluate the composition, richness, abundance, trophic

guilds, and frequency of occurrence of bird species in the urban area of Ouro Preto, a his-

toric city located in the Atlantic Forest biome of Brazil. We also evaluated the effects of

seasonality on the urban bird community and how the degree of urbanization influences

the richness and abundance of birds. Lastly, we compared bird richness and abundance

between historic and newly urbanized areas in the city using the Special Protection Zone

defined by the Master Plan of the city as a parameter.

We hypothesized that (1) the presence of green areas, such as gardens and parks, would

favor greater richness and abundance of bird species, especially of omnivores and grani-

vores; (2) there would be greater richness and abundance of birds in the city during the dry

season because more bird species and individuals will seek resources there; (3) areas with

a greater degree of urbanization will have lower bird richness and abundance; and (4) there

will be greater bird richness and abundance in historic protected zones. The results of this

study could assist managers in making decisions for the future growth of the city, through

the identification of priority areas for bird protection.

2 Research methodology

2.1 Study area

Recognized as Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity since 1980 by UNESCO, the

municipality of Ouro Preto (20° 23′ 28″ S, 43° 30′ 20 ″ W; Minas Gerais State, southeast-

ern Brazil) has a large urban heritage site. This situation allowed the maintenance of the

original urban structure, including a park, Horto do Contos, opened in 1799 in the central

T.Bhakti et al.

1 3

region (Pereira 2015). Horto do Contos is located within a protection zone that preserves

the region where the city originated, called the Special Protection Zone, that was deter-

mined by the city’s Master Plan (Ouro Preto 2006). Based on this, levels of protection and

maintenance of the region’s structure were defined, which prevent major urban and con-

struction changes in the region in the heritage site.

2.2 Bird sampling

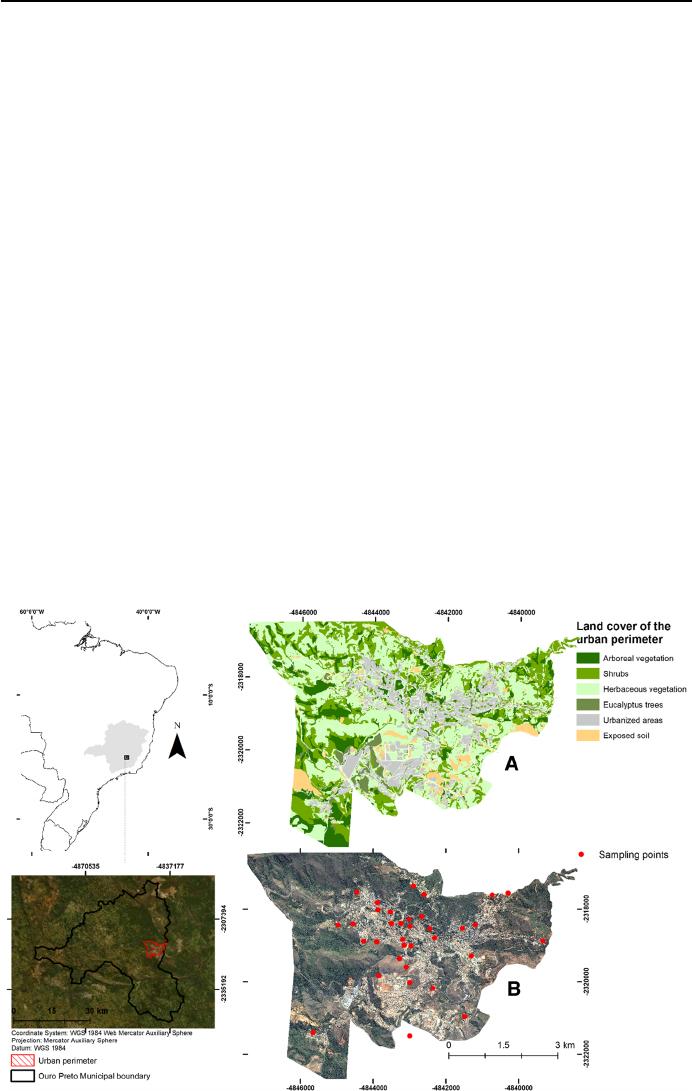

Birds were sampled by listening point counts at 35 counting points located on city streets

and distributed at least 300m from each other along the urban perimeter of Ouro Preto (as

determined by local legislation; Ouro Preto 2006) (Fig.1). Bird species and their abun-

dances were recorded at each point during 20-min sampling periods (Vergara etal. 2010;

Vielliard et al. 2010; Volpato etal. 2009). Sampling was carried out monthly between

August 2013 and December 2014 (except April and May 2014), between 6:00 and 9:00am,

for a total of 98days. The order that counting points were sampled was changed on each

sampling day so that all points were sampled equally at each hour of sampling (6:00 to

9:00am).

Bird species were classified according to their food preference (Lopes et al. 2005a,

2005b; Sabino etal. 2017; Schubart etal. 1965) (Table1), as well as their degree of end-

emism in relation to the Atlantic Forest biome (Vale etal. 2018). Scientific nomenclature

followed the rules of the Brazilian Committee for Ornithological Records (Piacentini etal.

2015). Bird richness was estimated by first-order Jackknife using EstimateS 8.2 software

Fig. 1 Location of the city of Ouro Preto (Minas Gerais State, southeastern Brazil), showing land use (a)

and the distribution of counting points (b) in the urban area of the city

Preservation ofhistorical heritage increases bird biodiversity…

1 3

(Colwell 2009). This estimate is based on the number of sampling units (each point count)

used and the presence or absence of species at each point (Develey 2003).

2.3 Data analysis

A map of coverage and land use provided by the Municipal Secretariat of Heritage of Ouro

Preto (Quickbird 2003 and 2006) was used for landscape analysis. The map divided the

urban perimeter into five classes: tree vegetation, shrub vegetation, herbaceous vegetation,

Eucalyptus vegetation, built area and exposed soil (Fig.1). To assess the presence of each

class at the counting points, 600m buffers were established and the proportion of each

class in the buffer was subsequently calculated. In addition, the size of the nearest forest

fragment and the distance of the nearest forest fragment were calculated for each count-

ing point. The proportion and the size and distance of the fragment closest to the counting

points (predictive variables) were related to bird species richness and abundance (response

variables) using Generalized Linear Models (GLMs).

Kernel density estimators (KDEs, Węglarczyk 2018) seek to estimate densities based

on local information, instead of estimating global parameters for data models. They use a

group of density probability functions called kernels, which produce a usage distribution

(He etal. 2020). Such estimators perform a count of all points within a region of influ-

ence, weighting them by the distance between points. A kernel is considered accurate at

assessing the distribution of the locations of individuals (Jacob and Rudran 2003; Laver

and Kelly 2008). KDEs were estimated to determine the areas within the city of Ouro Preto

that possesses the greater richness and abundance of birds. Values of kernel density were

classified according to density level, for species richness and abundance, through the Natu-

ral Breaks method of ArcGIS software, to guarantee maximum difference between gener-

ated classes (Baz etal. 2009).

The influence of season (dry and rainy seasons) and the Special Protection Zone (his-

torical sites and new areas) (predictive variables) on bird richness (response variable) was

evaluated by constructing Generalized Linear Mixed Models (GLMMs). Complementa-

rily, Permutational Analysis of Variance (PERMANOVA) was used to determine whether

species composition varied between seasons. The dry season was considered between the

months of April and September and the rainy season between the months of October and

Table 1 Feeding guilds, and their characteristics, used to classify bird species found within the urban

perimeter of the city of Ouro Preto

Feeding guild Characteristics

Insectivores (INS) Species whose diet consists of three-fourths or more of insects and other arthro-

pods

Omnivores (ONI) Species whose diet is composed of plant and animal material in similar propor-

tions

Frugivores (FRU) Species whose diet consists of three-fourths or more of fruits

Granivores (GRA) Species whose diet consists of three-fourths or more grains

Nectarivores (NEC) Species whose diet is predominantly composed of nectar, but also includes insects

and other arthropods

Carnivores (CAR) Species whose diet consists of three-fourths or more of live vertebrates

Necrophages (NECRO) Species whose diet consists of three-fourths or more of dead animals

Piscivores (PIS) Species whose diet is predominantly composed of fish

T.Bhakti et al.

1 3

March. Permutational Analysis of Multivariate Dispersion (PERMDISP) was performed to

measure data dispersion. The graphic representation of variation in the composition of bird

species between seasons was done using Non-metric Multidimensional Scaling (NMDS).

All analyses were performed using R software version 3.1.0 (R Development Core Team

2015).

3 Results

One hundred and fifty-one bird species representing 39 families and 18 orders were

recorded during a total of 294 sampling hours (TableS1 Supplementary material). The

most represented order was Passeriformes with 97 species, corresponding to 64.2% of

all registered species. The most represented passeriform family was Tyrannidae with 29

species (19.2%), followed by Thraupidae with 27 species (17.9%). Apodiformes was the

next most represented order, with the family Trochilidae having ten species (6.6%). The

observed bird species richness was 86.29% of the estimated richness for the urban perim-

eter of Ouro Preto (species accumulation curve in Fig. S1 Supplementary material).

There was a predominance of insectivorous bird species (63 species, 42%), followed

by omnivores (37 species, 24%), granivores (14 species, 9%), frugivores (13 species, 9%),

nectarivores (11 species, 7%), carnivores (nine species, 6%), piscivores (three species, 2%),

and necrophages (one species, 1%).

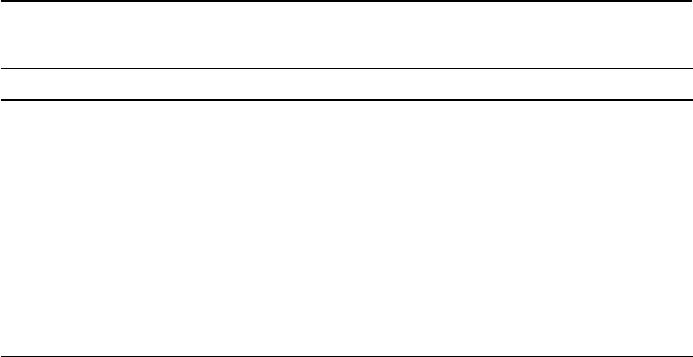

The highest values found for kernel density for both richness and the abundance of

bird species were in the region around Horto dos Contos (Fig.2), which is in the Historic

Center of the city of Ouro Preto.

Fig. 2 Kernels built to show the areas with the greatest richness (a) and abundance (b) of bird species

within the urban perimeter of the city of Ouro Preto (in red), Minas Gerais, Brazil. The black line indicates

the Special Protection Zone (a, b, c), while the orange line indicates the area of Horto dos Contos (c)

Preservation ofhistorical heritage increases bird biodiversity…

1 3

Twenty of the recorded species are considered endemic to the Atlantic Forest biome

(Table S1 Supplementary material), including Aramides saracura, Florisuga fusca,

Leucochloris albicollis, Pyriglena leucoptera, Lepidocolaptes squamatus, Mionectes

rufiventris, Knipolegus nigerrimus, Turdus subalaris, and Tangara desmaresti. Only the

species Sporophila frontalis was present on the list of endangered animals of Brazil,

with the status of Vulnerable (MMA 2014). This species was registered only in Horto

do Contos.

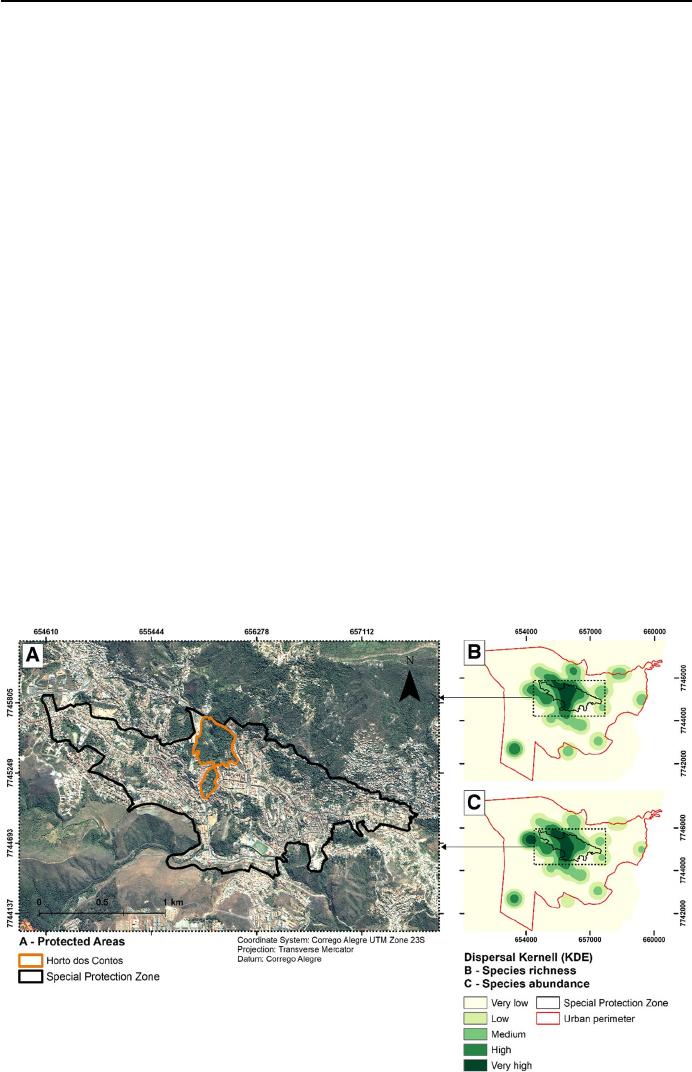

The following positive results were found for the analysis of buffers with the soil

cover and for the size and distance of the nearest forest fragments in relation to the

counting points: (1) bird species richness: herbaceous vegetation (F = 11.67 and

p < 0.001) (Fig.3a) and tree vegetation (F = 26.28 and p < 0.001) (Fig.3b); (2) bird spe-

cies abundance: herbaceous vegetation (F = 12.04 and p < 0.001) (Fig.3c) and tree veg-

etation (F = 24.37 and p < 0.001) (Fig.3d). There was a significant relationship between

bird abundance and proximity to the nearest forest fragment (F = 7.97 and p = 0.005).

All other relationships tested were not significant.

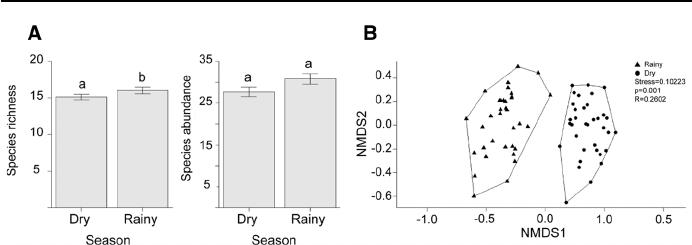

Bird richness was significantly related to seasonality (DF = 1; X

2

= 5.29, p = 0.021)

(Fig.4a), with greater richness during the rainy season. No significant seasonal changes

in bird abundance were observed (Fig.4a). A comparison of the species composition

of bird communities between seasons revealed two distinct groups, one for each season

(PERMANOVA: Season: DF = 1; r2 = 0.26, p = 0.001; PESMIDISP: DF = 1; F = 17.46,

p < 0.001) (Fig.4b).

Bird richness was lower in the Special Protection Zone (Historic Center; T = 38.63

and p < 0.001), while bird abundance was lower at counting points outside the Special

Protection Zone (newly urbanized areas: T = 13.24 and p < 0.001).

Fig. 3 Positive relationships between bird richness and the amount of herbaceous (a) and tree (b) vegeta-

tion, and between bird abundance and the amount of herbaceous (c) and tree vegetation (d) in the city of

Ouro Preto

T.Bhakti et al.

1 3

4 Discussion

All of the evaluated parameters influenced, to some degree, bird species richness and abun-

dance. The presence of green areas influenced the urban bird community, with greater rich-

ness and abundance of bird species in areas with more herbaceous plants and trees. Addi-

tionally, bird species abundance increased with increasing proximity of forest fragments.

The urban bird community of Ouro Preto changed seasonally with greater richness during

the rainy season. Increasing degree of urbanization negatively influenced bird species rich-

ness and abundance, with more bird species and individuals in less urbanized areas, such

as Horto dos Contos. Finally, the Historic Center had lower bird richness but higher bird

abundance than did newly urbanized areas. This result demonstrates that maintaining green

spaces in urban centers can mitigate the expected negative impacts of urbanization since

small patches of vegetation can serve as favorable habitats for bird species. In the case of

Ouro Preto, the area located within the Historic Center has experienced little change to its

structure since 1950 (Oliveira 2004). Thus, the shape and number of buildings (i.e., how

much they occupy within the lots) have remained practically fixed, including backyards,

vegetable gardens, and other green areas, which favors the occurrence of bird species on a

local scale (Bhakti etal. 2018).

This argument is corroborated by the presence of a greater density of bird richness and

abundance near Horto dos Contos, which is in the Historic Center of the city. However,

when only bird richness and abundance are evaluated, the central region had more birds

(greater abundance), but fewer species (less richness). Although this result seems contra-

dictory, when evaluating the results of the kernel analysis, it is possible to observe that the

greatest richness and abundance were concentrated almost exactly in the area of Horto dos

Contos, reaching areas out of the Special Protection Zone (Fig.2). Horto dos Contos rep-

resents an old protected forested area with minimal management of the vegetation, which

is important for maintaining local diversity (Kümmerling and Müller 2012). Thus, Horto

dos Contos has greater structural complexity and larger microenvironments than do back-

yards and squares in the same area, facilitating the occurrence of a greater richness of bird

species. Furthermore, this area practically functions as an ecological corridor linking the

Historic Center to green protected areas throughout the city.

The greater abundance of birds in the Historic Center could also be related to the pres-

ence of a greater number of nesting and foraging areas. Roof ceilings, gaps between old

beams, chimneys, architectural pieces on old church facades and old, vegetated windowsills

Fig. 4 a Differences in bird richness and abundance between the dry season and the rainy season in the city

of Ouro Preto (different letters indicate significant differences between seasons). b Bird species composition

in the dry season (circles) and in the rainy season (triangles) in the city of Ouro Preto

Preservation ofhistorical heritage increases bird biodiversity…

1 3

can be nesting sites for several of the species observed in the Historic Center of Ouro Preto.

Gardens and backyards, full of ornamental plants, can be feeding places for frugivorous,

granivorous, insectivorous, and nectarivorous birds. The presence of nesting and forag-

ing areas was related to a greater richness and abundance of birds in farmlands of Poland

(Rosin etal. 2016). On the other hand, the modernization of buildings in cities of Poland

decreased by 50% the abundance of building-nest birds (Rosin etal. 2020), showing that

new areas in cities can negatively impact the avifauna. A decrease in bird abundance out-

side the Historic Center was also observed in the present study.

Measures of species richness in urban environments are relevant for understanding the

different stages of landscapes that are responsible for the impoverishment of biological

diversity (Clergeau etal. 2002; Melles etal. 2003). Therefore, assessing the permeability

of an urban area is important, which we emphasize here with the large number of bird

species found (151). We associate this large number of bird species with the presence of

areas with herbaceous and tree vegetation, which was more important than the presence of

other land coverings, including urbanized areas, to the maintenance of birds. The number

of species associated with herbaceous and tree vegetation also reinforces the positive role

of heterogeneous environments for conserving biodiversity and reducing homogenization

of the urban bird community (Callaghan etal. 2019; Castro Pena etal. 2017; Chang and

Lee 2016).

Another important parameter that may be contributing to the high richness and abun-

dance of birds within the urban perimeter of Ouro Preto is the presence of large Conserva-

tion Units adjacent to the city (Silva etal. 2015). These units may act as source fragments

for birds that occur within the urban area, resulting in an increase in the richness and abun-

dance of birds (Casas etal. 2016), especially if there are green areas that allow this con-

nection (Snep etal. 2006). This point is highlighted by the increase in species richness and

abundance in the most distant points from the central region, which are close to peri-urban

areas, in addition to the relationship between the occurrence of bird species and the size

of the nearest forested area. Thus, peri-urban regions can play a role as strategic areas for

protection, mainly because they are areas that suffer great impacts from the growth of cities

(Aguilar 2008).

The Atlantic Forest has been reduced to just 10% of its original coverage, with most of

the remaining fragments being small and altered (Harris and Pimm 2004). Given to this

drastic reduction in forest cover and the high number of endemic bird species found in the

study area, we showed that the sampled landscape has important characteristics for the per-

sistence of species in the biome (Aronson etal. 2014; Plass and Jr 2013). This result sug-

gests the importance of assessing local biodiversity for urban planning and that city growth

must consider the presence of large areas of tree and herbaceous vegetation, as these are

capable of acting as areas of refuge for local avifauna.

Seasonality influenced the dynamics of the urban bird community in Ouro Preto, with

a positive correlation between species richness and the rainy season. This result was not

expected since increases in bird richness and abundance are generally observed in cities

during the dry season (Asefa etal. 2017; Girma etal. 2017). In the dry season, a period

of resource scarcity, changes in weather have greater influences on species in natural areas

because competition for resources increases, which may not occur in urbanized environ-

ments (Coogan etal. 2018; Ferger etal. 2014; Mulwa etal. 2013). Some species may find

urbanized areas attractive during times of adversity since the resources made available by

human activity are abundant in any season (Chace and Walsh 2006; Coogan etal. 2018;

Støstad etal. 2017). However, our results showed an increase in bird richness during the

rainy season. The rainy season coincides with the summer in Brazil, which is when many

T.Bhakti et al.

1 3

migrant species arrive in the region for reproduction, such as Cyclarhis gujanensis and

Ammodramus humeralis (Pinho etal. 2017; Somenzari etal. 2018), which could be respon-

sible for this result.

Insectivorous and omnivorous feeding preferences were the most common among bird

species in Ouro Preto. This result does not corroborate other studies that found insectivo-

rous species to be rare in urban centers (Sengupta etal. 2014; Seress and Liker 2015).

Insectivores are the most common birds in lists made in tropical natural areas due to their

use of different habitats and vegetation strata, ranging from understory birds to those liv-

ing in open areas (Anjos 2002; Hayes etal. 2020). The presence of many shrub and tree

patches in the urban center of Ouro Preto seems to facilitate the occurrence of insectivo-

rous species, probably due to available food and microhabitats, which reinforces the impor-

tance of maintaining such green areas in the urban matrix. Granivorous species, which,

due to their ample feeding, persist more easily in urban areas, were also widely observed.

Frugivores are more limited in terms of food and can thus experience local reductions

(Cleary etal. 2007; Gray etal. 2007; Kennedy etal. 2010), although the landscape of Ouro

Preto, due mainly to the presence of backyards with orchards, allows the existence of this

guild of birds. Granivores were associated mainly with open areas and, thus, were favored

by the large amount of herbaceous vegetation. These results are indicative of the heteroge-

neity of the landscape, which allows the occurrence of a wide variety of species of different

feeding guilds.

Finally, it is important to remember that this study was conducted in only one historic

city of Brazil and that the results need to be carefully considered, avoiding generalization.

Thus, the topics in the conclusion should be linked to the results found in the present study,

although suggesting a wide application. Further studies should be conducted in other his-

toric cities to assess whether the results presented in this study are repeated, increasing the

evidence of the importance of historic centers in maintaining a high diversity of birds in

cities.

5 Conclusion

•

Historical areas within cities are important for the conservation of bird species since

the lack of changes to them maintains, over time, small areas of vegetation that can

provide shelter and food for birds or function as stepping stones to larger forested areas

present in the vicinity.

•

Small green areas in historic cities can be relevant to the permeability of the urban

matrix for local biodiversity, especially when they provide heterogeneous environ-

ments.

•

Preserving the structure of ground cover not only leads to the protection of green areas,

but also favors the long-term maintenance of urban avifauna, including trophic guilds

that are not common in urban areas.

Acknowledgements Authors would like to thank the staff of the transport section of the Federal University

of Ouro Preto, Capes-Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior for POM scholarship,

and RJY for English revision of the manuscript.

Author contributions CSA and POM conceived the project, designed research, and revised the manuscript.

POM, EFA, and FR collected and analyzed data. CSA, TB, and MAGF analyzed data and drafted the

manuscript.