ORIGINAL PAPER

Antioxidant activity and hepatoprotective potential

of Hammada scoparia against ethanol-induced

liver injury in rats

Ezzeddine Bourogaa & Riadh Nciri &

Raoudha Mezghani-Jarraya &

Claire Racaud-Sultan & Mohamed Damak &

Abdelfattah El Feki

Received: 20 April 2012 / Accepted: 2 August 2012 / Published online: 15 August 2012

#

University of Navarra 2012

Abstract The present work was aimed at studying the

antioxidative activity and hepatoprotective effects of

methanolic extract (ME) of Hammada scoparia leaves

against ethanol-induced liver injury in male rats. The

animals were treated daily with 35 % ethanol solution

(4 gkg

−1

day

−1

) during 4 weeks. This treatment led to an

increase in the lipid peroxidation, a decrease in antiox-

idative enzymes (catalase, superoxide dismutase, and

glutathione peroxidase) in liver, and a considerable in-

crease in the serum levels of aspartate and alanine ami-

notransferase and alkaline p hospahata se. However,

treatment with ME protects efficiently the hepatic func-

tion of alcoholic rats by the considerable decrease in

aminotransferase contents in serum of ethanol-treated

rats. The glycogen synthase kinase-3 β was inhibited

after ME administration, which leads to an enhancement

of glutathione peroxidase activity in the liver and a

decrease in lipid peroxidation rate by 76 %. These

biochemical changes were consistent with histopatho-

logical observations, suggesting marked hepatoprotec-

tive effect of ME. These results strongly suggest that

treatment with methanolic extract normalizes various

biochemical parameters and protects the liver against

ethanol induced oxidative damage in rats.

Keywords Hammada scoparia

.

Methanolic extract

.

Oxidative stress

.

Hepatoprotective effect

Introduction

Alcohol abuse and alcoholism are serious current

health and socioeconomic problems throughout the

world. Despite great progre ss made in the field, the

development of suitable medications for the treatment

of alcoholism remains a challeng ing purpos e for alco-

hol research. Ethanol is almost exclusively metabo-

lized in t he cytosol and mitochondria by enzyme

catalyzed oxidative processes [26]. In fact, the liver

accounts for 90 % of alcohol metabolism and is the

most adversely affected organ [16]. Thr ee pathologi-

cally life-threatening liver diseases induced by alcohol

abuse are fatty liver (steatosis), hepatitis, and cirrhosis.

Moreover, oxidative stress is a central etiological

factor in various pathologies. In vertebrates for example,

a major defense mechanism against oxidative stress is

J Physiol Biochem (2013) 69:227–237

DOI 10.1007/s13105-012-0206-7

E. Bourogaa (*)

:

R. Nciri

:

A. El Feki

Laboratoire d’Ecophysiologie Animale,

Faculté des Sciences de Sfax,

PB 1171, 3000 Sfax, Tunisia

e-mail: [email protected]om

R. Mezghani-Jarraya

:

M. Damak

Laboratoire de Chimie des Substances Naturelles,

Faculté des Sciences de Sfax,

PB 1171, 3000 Sfax, Tunisia

C. Racaud-Sultan

INSERM, U563, Centre de Physiopathologie de Toulouse

Purpan, Université Toulouse III Paul Sabatier,

Toulouse, France

orchestrated by the transcription factor Nrf2, which

regulates the expression of antioxidant phase II genes

[24]. Some of the best known enzymatic antioxidants

are glutathione reductase, glutathione peroxydase

(GPx), catalase (CAT), and superoxide dismutase

(SOD), which convert active oxygen molecules into

non-toxic compounds [2, 25]. Alcohol-induced oxida-

tive stress is linked to the metabolism of ethanol involv-

ing b oth microsomal and mitochondrial systems.

Ethanol metabolism is directly involved in the produc-

tion of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and rea ctive

nitrogen species [21]. These form an environment fa-

vorable to oxidative stress. Ethanol treatment results in

the depletion of the endogenous antioxidants (SOD,

CAT, and GPx) in liver.

It has also been reported that oxidative stress resis-

tance is modulated by a glycogen synthase kinase-3

(GSK-3) whose two highly homologous forms in

mammals were identified as GSK-3β and GSK-3α.

GSK-3β activity, on the one hand, is regulated by

phosphorylation of the Ser

9

position (inactive form)

and Tyr

216

position (active form) [19]. On the other

hand, GSK-3β, a constitutively active serine/threonine

kinase, which was initially described as a key enzyme

involved in glycogen metabolism, is known to regu-

late diverse cell function pathways [7].

Medicinal plants or the isolated bioactive constitu-

ents form one of the major sources of raw materials for

drugs [ 3 ] in preventive and/or curative applications.

Public, academic, and government interests in tradi-

tional medicines are growing exponentially due to the

increased incidence of the adverse drug reactions and

economic burden of the modern system of medicine.

Many natural products have been reported as having

an inhibitory effect on previous ethanol absorption,

thus being an alternative to synthetic medicines in

the prevention of alcohol-provoked liver damage and

dysfunction. The leaves of Hammada scoparia (com-

monly known in Tunisia as Rimth; Family: Chenopo-

diaceae) have widely been used in traditional medicine,

prevention of several disorders as cancer, hepatitis,

inflammation, a nd obesity [9].

Our recent studies also showed that H. scoparia

leaves extract possess a molluscicidal activity of the

principal alkaloids against Galba truncatula [15] and a

potent anti-tumoral activity [4, 5].

Regarding t he ability of natural’s compoun ds to

reduce alcohol liver diseases, we proposed that hexane

extract (HE), dichloromethane extract (DE), and

methanolic extract (ME) of H. scoparia might possess

significant capacities to reduce tissue injuries induce by

alcohol in an in vivo conditio ns. For that case, we

planned to evaluate the aminotransferases and endoge-

nous antioxidants in serum and liver of rats.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

Hammada scoparia (Pomel) Iljin belongs to the Cheno-

podiaceae family and is locally known as “Rimth” in

T unisia. The plant was collected in southern Tunisia in

June 2007. A voucher specimen no. LCSN100 was de-

posited at “the Chemistry Laboratory of Natural Substan-

ces, Sfax Faculty of Science (Tunisia).” The leaves were

carefully detached from the fresh plant and air dried.

Preparation of extracts

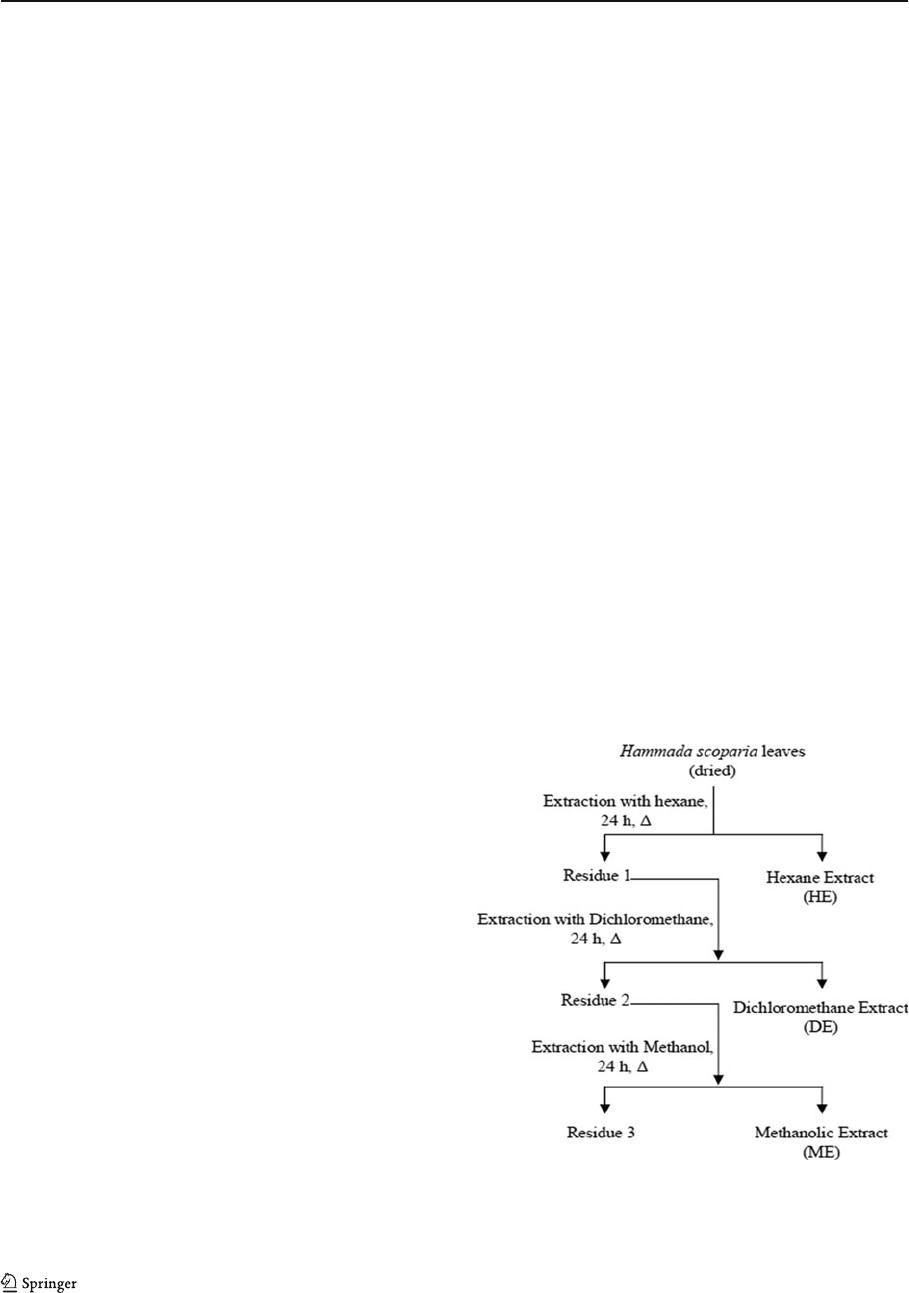

Air-dried leaves (200 g) of H. scoparia were extracted

consecutively during 24 h each time, using a Soxhlet

apparatus by increasing various polarity solvents

(Fig. 1), hexane, dichloromethane, and methanol. All

solvents were evaporated under reduced pressure, and

the extract was dried to yield the hexane extract (HE,

1.05 % w /w), the dichloromethane extract (DE, 2.27 %

Fig. 1 Successive extractions of leaves of Hammada scoparia

using three solvents: hexane, dichloromethane, and methanol

(an increasing order of polarity)

228 E. Bourogaa et al.

w/w), and the methanolic extract (ME, 15.07 % w/w).

These extracts were stored under refrigeration for fu-

ture use. The concentration used in the experiment was

based on the dry weight of the extract.

Phytochemical screening

The preliminary phytochemical screening was per-

formed according to the Harborne method [12]. Plant

extracts (hexane, dichloromethane, and methanol)

were subjected to chemical tests for the presence of

sterols, triterpenoids, carotenoids, tropolons, quinons,

alkaloids, and flavonoids.

Determination of total phenolic content

Determination of total polyphenolic content i n the

extracts of H. scoparia leaves expressed in terms of

gallic acid was measured by the modified Folin–Cio-

calteu procedure [28]. Briefly, 1 ml of sample (1 mg/

ml) was mixed with 1 ml of Fo lin – Ciocalteu reagent.

After 3 min, 1 ml of saturated Na

2

CO

3

solution was

added to the mixture and adjusted to 10 ml with

distilled water. The reaction was kept in the dark for

90 min, after w hich the absorbance was read at

725 nm, and the total polyphenol concentration was

calculated from a calibration curve using gallic acid as

standard.

DPPH assay

2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical scav-

enging capacity of plant extracts represents the free

radical reducing activity of compounds based on one-

electron reduction. Briefly, 1.5 ml of DPPH solution

(10

−5

M, in ethanol 95 %) was incubated with 1.5 ml

of plant extract at varying concentrations (0.01−1 mg).

The reaction mixture was shaken well and incubated

in the dar k for 30 min at room temperature. The

control was prepared as above without any extract.

The absorbance of the solution was measured at

517 nm against a blank. Percentage of DPPH scav-

enged by all extracts at varying concentrations was

calculated as follows:

% Inhibition ¼ A

blank

A

sample

=A

blank

100

where A

blank

is the absorbance of the control reaction

containing all reagents except the sample, and A

sample

is the absorbance of the sample. Extract concentration

providing 50 % inhibition (IC50) of DPPH was calcu-

lated from the graph of inhibition percentage against

extract concentration. Ascorbic acid and α-tocopherol

were used as standards.

Antioxidant assay using the β-carotene bleaching

method

The oxidative losses of β-carotene/linoleic acid emul-

sion were used to assess the antioxidation ability of the

extracts of H. scoparia leaves. One milligram of β-

carotene was dissolved in 10 ml of chloroform, and

1mlβ-carotene solution was mixed with 20 mg of

linoleic acid and 200 mg of Tween 40 emulsifier in a

round-bottom flask. The chloroform was removed by

nitrogen gas, and 50 ml of oxygenated distilled water

was added slowly to the semisolid residue with a

vigorous shaking, to form an emulsion. An absorbance

at 470 nm was immediately recorded after adding 2 ml

of the sample to the emulsion, which was regarded as

t0 0 min. The round-bottom flasks were capped and

placed in an incubator at 50 °C. The absorbance at

470 nm was determined every 15 min until 120 min. A

second emulsion, consisting of 20 mg of linoleic acid

and 200 mg of Tween 40 and 50 ml of oxygenated

water, was also prepared and served as blank to zero

the spectrophotometer. The antioxidan t activity coef-

ficient (AAC) was calculated accordi ng to the follow-

ing equation:

AAC ¼ A

A 120ðÞ

A

C 120ðÞ

= A

Cð0Þ

A

C 120ðÞ

1000

where A

A(120)

is the absorbance of the antioxidant at

120 min, A

C(120)

is the absorbance of the control at

120 min, and A

C(0)

is the absorbance of the control at

0 min. The AAC was calculated from the graph of

absorbance against time. Butylated hydroxytoluene

(BHT) and α-tocopherol were used as standards.

Animals and treatments

Male Wistar rats weighing 150±25 g, obtained from

the breeding center, Central Pharm acy of Tunis

(Tunisia), were used for the study. They were housed

in cages (six animals per cage) placed in a breeding

farm maintained at 23 °C, equipped with a ventilation

system and light controlled conditions (10 h dark and

14 h light). These animals were allowed free access to

Hepatoprotective potential of H. scoparia 229

a standard dry pellet diet supplied by the Industrial

Society of Concentrates, (SICO, Sfax, Tunisia). The

rats were acclimatized to laboratory conditions for

7 days before the beginning of the experiment. The

animals were maintained in accordance with guide-

lines for animals care per the Sfax Faculty of Science,

Tunisia.

The rats were randomly divided into five groups of

six males, as follow s:

Group 1 (control) Served as untreated control and

received i.p. injections of 9‰

NaCl

Group 2 (EtOH) Orally administered with 4 g eth-

anol (35 %)/kg b.w. to induce

liver damages

Group 3 (HE) Given the same dose of ethanol

andinjectedi.p.withHEat

200 mg/kg b.w.

Group 4 (DE) Treated with ethanol and injected

by DE 200 mg/kg b.w.

Group 5 (ME) Treated with ethanol and injected

by ME 200 mg/kg b.w.

All extracts (HE, DE, and ME) were evaporated

and dissolved in ethano l/H

2

O (1/9, v/v) before admin-

istration to animals. The administration of ethanol

started 3 days bef or e treatment with plant extracts

and was maintained until the end of treatment.

At the end of the 4-week experimental period, the

rats were killed by decapitation. Blood samples were

collected, and livers were removed and weighed after

the removal of the surrounding connective tissues.

Blood analys is

The hematological parameters [red blood cell (RBC),

white blood cell (WBC), and hematocrit] were deter-

mined using an autoanalyzer (Coulter Maxem). Serum

aspartate and alanine aminotransf erases (AST and

ALT) and alkaline phosphatase (ALP), activities were

determined using commercial kits supplied by Sigma

Munich (Munich, Ge rmany) and Boehringer Man-

nheim (Mannheim, Germany).

Oxidative stress parameters

Oxidative stress analysis was performed by the

examination of thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances

(TBARS) and SOD, CAT, and GPx activities. The

preparation of the liver tissue was as follows. One gram

of liver tissue was homogenized in 2 ml TBS (50 mM

Tris, 150 mM NaCl, pH0 7.4) in an ultrasound homog-

enizer and centrifuged at 9,000 rpm for 15 min. The

supernatants were removed and stored at −80 °C for

subsequent analysis.

TBARS assay

As a marker of lipid peroxidation, the TBARS con-

centration was measu red based on the method of

Esterbauer et al. [10]. Briefly, 250 μl of the superna-

tant was mixed with 100 μl TBS buffer, 250 μlof

trichloroacetic acid–BHT (20 %− 1 %), vortexed and

then centrifuged at 1,000 rpm for 10 min. Besides,

400 μl of the collected supernatant was mixed with

80 μl HCl (0.6 M), 320 μl of Tris-TBA (26 mM–

120 mM), vortexed, and then incubated at 80 °C for

10 min. The resulting coloured upper layer was mea-

sured at 532 nm. The TBARS concentration was

calculated by referring to the extinction coefficient

of TBARS (1.56×10

5

M

−1

cm

−1

) and expressed per

milligram of protein.

Superoxide dismutase

The activity was determined at 25 °C by measuring its

ability to inhibit the photoreduction of nitroblue tetrazo-

lium (NBT) to the blue formazan [8]. The assay was

performed in an aerobic m ixture consisting of PBS

(50 mM), methionine (13 mM), EDTA (0.1 mM) ribo-

flavine (2 μM), and NBT (75 μM). The activity was

expressed as units/milligram protein, 1 U being the

amount inhibiting the photoreduction of NBT by 50 %.

Catalase

The catalase (CAT) activity was determined by mea-

suring the decrease in absorbance at 240 nm for 2 min

at 25 °C of H

2

O

2

(final concentration 20 mM) accord-

ing to the metho d of Aebi [1]. CAT activity was

expressed as micromoles of H

2

O

2

destroyed/minute/

milligram protein at 25 °C.

Glutathione peroxidase

The GPx activity was assayed at 25 °C according to the

method of Flohé and Günzler [11]withsomemodifica-

tions. The activity was measured in 250 μl cellular

230 E. Bourogaa et al.

extract mixed with GSH (final concentration, 0.35 mM).

Reactions were started with the addition of H

2

O

2

(0.2 mM). After the reactions were stopped, 5,5′-dithio-

bis-2-nitrobenzoic acid was added, and the absorbance

was recorded at 412 nm. Such activity was expressed as

micromoles of GSH oxidized/minute/gram protein.

Histological examination

A portion of liver was processed by routine histology

procedure. After fixation in Bouin solution, pieces of

fixed tissue were embedded into paraffin, cut into

5 μm slices, a nd colored with hematoxylin–eosin.

For evaluation of histological alterations, these slides

were observed under light microscop e.

Electrophoresis and Western blotting

For Western blot analysis, liver tissues (1 g) were re-

duced in Laemmli sample buffer, sonicated, and boiled

for 3 min. Proteins were then resolved on sodium

dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

(SDS-PAGE) and transferred to nitrocellulose mem-

brane (Hybond-C Super, Amersham Pharmacia Bio-

tech). The membrane was block ed for 1 h in TBS-

Tween 0.05 % (TBS-T) containing 5 % of milk.

Blocked membranes were then blotted with antibodies

anti-GSK3β (BD Transduction Laboratories) and anti-

phospho Ser9 GSK3 (Biosource International) over-

night at 4 °C, washed twice with TBS-T, and

incubated for 1 h with horseradish-peroxidase-coupled

secondary antibody (Cell Signalling). After three addi-

tional washes, detection was achieved with Pierce

Supersignal chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce).

Statistical analysis

The results are expressed as mean±SEM. The signif-

icance of the differences between the control and the

treatment was established by the Student’s t test for

independent samples (P<0.05).

Results

Characterization of H. scoparia extracts

The results of the preliminary phytochemical screen-

ing method are illustrated in Table 1. In fact, the

chemical tests performed in DE and ME extracts for

sterols, triterpenoids, carotenoids, tropolons, and qui-

nons were negative. However, the chemical test per-

formed for alkaloids was positive in ME and very

important in DE, while the chemical test for flavo-

noids was positive only for ME. Moreover, phenolic

contents of the plant extracts were evaluated using the

Folin–Ciocalteu reagent. Analysis shows the yield and

the phenolic content in H. scoparia extract, expressed

as milligram of gallic acid equivalents per gram of

extract. ME showed a highest amount of phenolic

compounds (58.82±0.082 mg/g; Table 2).

The antioxidant activities of plant extracts were

evaluated by its ability to scavenge DPPH free radi-

cals. ME showed a scavenging activity with an impor-

tant decr ease of D PPH free ra dicals versus the

scavenging activity of α-tocopherol and ascorbic acid

(Table 3). In addition, AAC are summarized in Table 3

where the results showed that ME and BHT ha s a

comparable antioxidant activity.

Hematological parameters

The blood parameter levels such as RBC, WBC, and

hematocrit are represented in Table 4. Indeed, ethanol

administration increased WBC levels to 4.12±0.11

[from 3.25±0.12 in control groups (p<0.05)]. WBC

levels were significantly decreased (p<0.05) in animals

treated with ME (3.37±0.124).

Liver function

Ethanol administration affected biochemical markers

(AST, ALT, and ALP) of liver function. As shown in

Table 5, serum AST, ALT, and ALP levels were

Table 1 Chemical groups

present in the extracts from leaves

of Hammada scoparia

(−) No reaction, (+) positive

reaction, (++) important reaction

Sterols/

Triterpenoids

Carotenoids/

Triterpenoids

Tropolons Quinones Flavonoids Alkaloids

HE + −−−−−

DE −−−−−++

ME −−−−++

Hepatoprotective potential of H. scoparia 231

enhanced, compared to control group, in chronically

ethanol-treated rats (59, 55, and 71 %, respectively).

When animals were treated with H. scoparia extracts

(DE and ME), the activities of aminotransferases were

practically restored and reached the normal values of

control rats. Particularly, the beneficial effect of the

ME treatment on the biochemical parameters of liver

injury was highly significant (P<0.001).

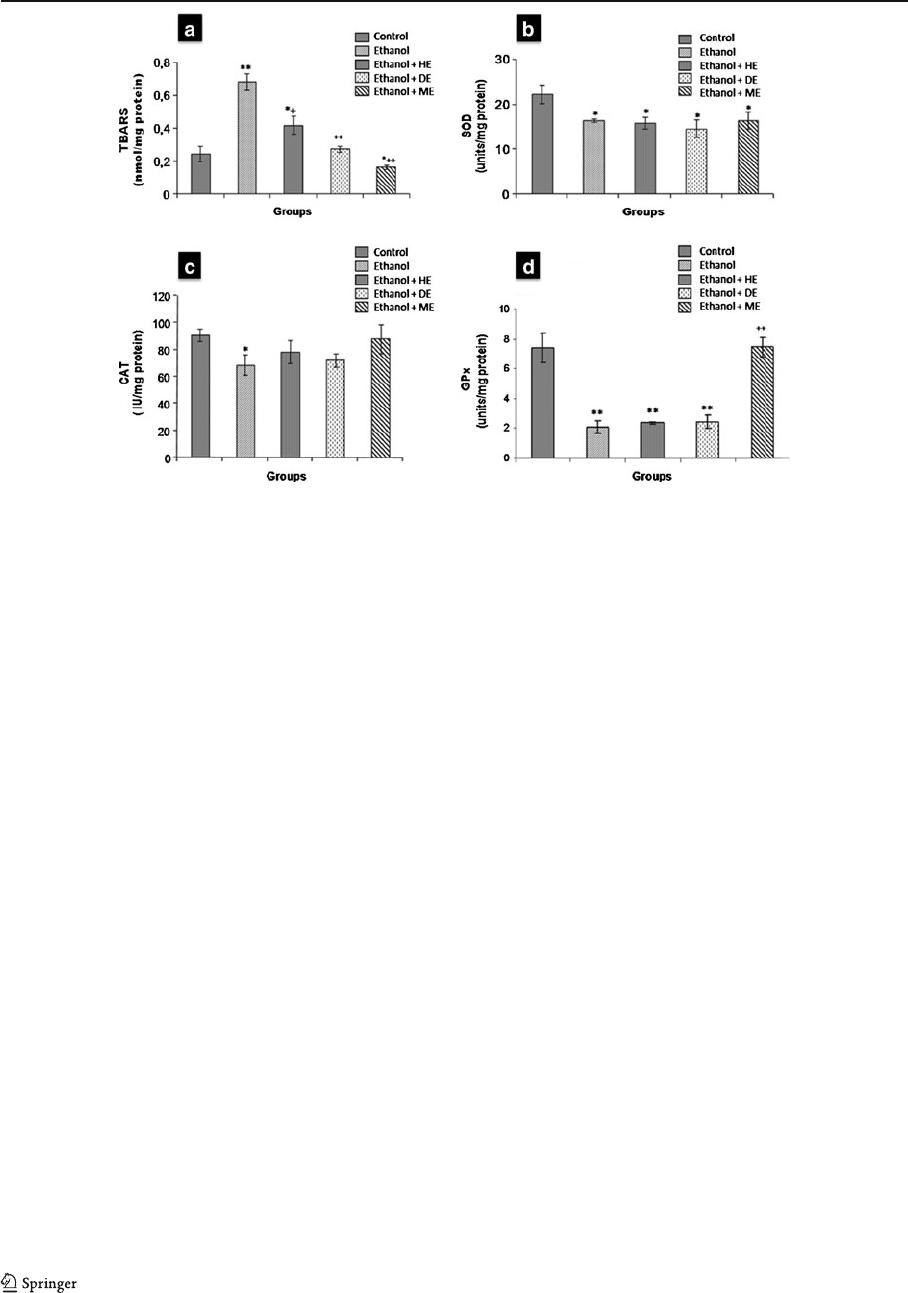

Evaluation of lipid peroxidation and antioxidant

enzymes (CAT, SOD, and GPx)

Liver TBARS levels, a lipid peroxidation marker,

increased significantly after alcohol treatment by a

factor of 2.8 compared with controls (Fig. 2a). This

effect was completely inhibited in the presence of H.

scoparia extracts, especially in ME extract enriched in

flavonoids (Table 1).

To evaluate the ability of ME to prevent ROS-

induced oxidative stress, SOD, CAT, and GPx activi-

ties were meas ured in liver homogenates. Figure 2b–d

shows that rats treated with ethanol exhibited a

marked decrease in the activities of SOD, CAT, and

GPx. Treatment with H. scoparia extracts (HE, DE,

and ME) could not repair the reduction in SOD and

CAT activities, while GPx activity was restored after

H. scoparia methanolic extract treatment.

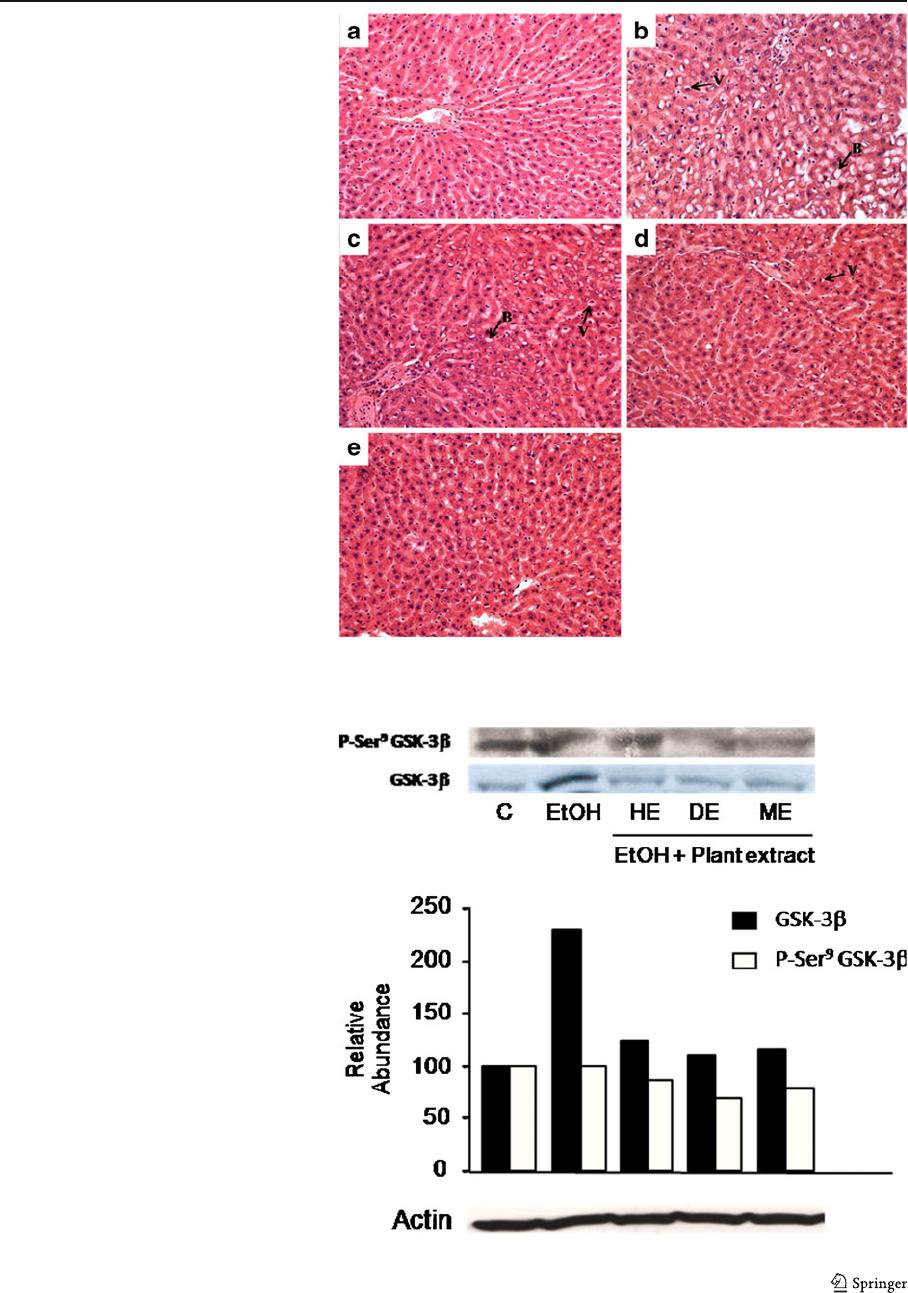

Histological examination showed a protective effect

of ME

The liver sections of ethanol-intoxicated rats proved

massive ballooning degeneration and cytoplasmic

vacuolization (Fig. 3b) compared to a normal histolo-

gy in control livers (Fig. 3a). The hepatocellular dam-

age was slightly reduced in ethanol-fed rats treated

with HE or DE (Fig. 3c, d). Nevertheless, the histo-

logical architecture of liver sections of the rats treated

with methanolic extract demonstrated prominent re-

covery in the form of maintained hepatic histoarchi-

tecture (Fig. 3e), such as reduced cytoplasmic

vacuolization and ballooning degeneration.

Glycogen synthase kinase

Immunoblot analysis was used to examine the conse-

quences of chronic ethanol consumption on total

GSK-3β in liver h omogenate. The data presented in

Fig. 4 show that GSK-3β was overexpressed after

ethanol treatment. However, ethanol was not able to

induce such effect in rats r eceiving H. scoparia

extracts (HE, DE, and ME). We suggest that ethanol

activates GSK-3β, which was demonstrated using the

anti-phospho Ser

9

GSK-3β anti body (Fig. 4).

Discussion

The liver is the major site of xenobiotic metabolism

and excretion. This organ accounts for 90 % of alcohol

metabolism. Indeed, it is the most adversely affected

organ after an excessive consumption of alcohol. The

alcohol absorbed from the intestinal tract gains access

first and foremost to the liver, resulting in a variety of

liver ailments. Thus, liver diseases remain one of the

serious health problems due to alcohol abuse [6].

In the present study, the hepatoprote ctive effect of

hexane, dichlorom ethane, and methanolic extracts of

H. scoparia leaves was evaluated in alcoholic rat

model a nd find out the therapeutically efficacious

extract. An attempt was made to find out the correlation

Table 2 The total phenolic content and antioxidant activities in

vitro (2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl and β-carotene bleaching

method)

Extract TPC (mg of gallic

acid equivalents/g)

HE (hexane extract) 9.76±0.030

DE (dichloromethane extract) 34.75±0.085

ME (methanol extract) 58.82±0.082

Total polyphenolic content in the extracts of H. scoparia leaves

expressed in terms of gallic acid

Table 3 The total phenolic content and antioxidant activities in

vitro (2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl and β-carotene bleaching

method)

Extract IC

50

(μg/ml) AAC

HE (hexan extract) 23.6 485

DE (dicloromethan extract) 6.3 606

ME (methanolic extract) 2.6 666

α-Tocopherol (antioxidant reference) 5.5 805

Ascorbic acid (antioxidant reference) 3.5 –

BHT (antioxidant reference) – 753

DPPH-scavenging activity of plant extracts (IC

50

) and antioxi-

dant assay using the β-carotene bleaching method (AAC anti-

oxidant activity coefficient)

232 E. Bourogaa et al.

between antioxidant and hepatoprotective activity. In

fact, ethanol is being used extensively to investigate

hepatoprotective activity on various experimental ani-

mals. Its administration induces oxidative stress either

by enhancing the production of ROS and decreasing the

level of endogenous antioxidants [13]. Moreover, etha-

nol is readily absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract.

Actually, only 2–10 % is eliminated through the kidneys

and the lungs, the rest is oxidized in the body, first and

foremost in the liver [17]. A major defense mechanism

involves the antioxidant enzymes, including SOD, CAT,

and GPx, which convert active oxygen molecules into

nontoxic compounds.

Besides, excessive use of alcohol induces lipid

peroxidation (when free radicals are formed), damages

the liver cells membranes and o rganelles, and causes

the swelling and necrosis of hepatocytes, resulting in

the release of cytosolic enzymes such as AST, ALT,

and ALP into the circulating blood [32].

The ethanol oxidizing system takes place in micro-

somes, involving an ethanol-inducible cytochrome

P450 (2E1). After chronic ethanol consumption, there

is a four- to tenfold induction of P450 (2E1) expres-

sion, associated not only with increased acetaldehyde

generation but a lso with the production of oxygen

radicals that promote lipid peroxidation [18, 22, 29].

In this view, the reduction in AST, ALT, and ALP

activities by metha nolic extracts is an indication of the

stabilization of plasma membrane as well as a repair of

hepatic tissue damage caused by ethanol. This effect is

in agreement with the commonly accepted view that

serum activities of aminotransferases return to normal

with the healing of hepatic parenchyma and regenera-

tion of hepatocytes [30]. Alkaline phosphatase is the

prototype of these enzymes that reflects the patholog-

ical alteration in biliary flow.

Thus, the administration of methanolic extract of

leaves reveal ed hepatoprotective activity of H. scopa-

ria leaves against the toxic effect of ethanol, which

was also supported by histopathological studies.

Reduced lipid peroxidation was revealed by signif-

icant decrease in TBARS level in groups treated by

extracts, especially in ME extract enriched in flavo-

noids. Furthermore, histopatholog ical studies under

light microsco pe confirm th e preventive effect of

metanolic extract agains t ethanol induced liver dam-

age as shown by the decrease in the severity of toxic

effects of ethanol (vacuolization and ballooning). This

Table 4 Blood parameters of rat after chronic ethanol administration treated with or without H. scoparia extracts (HE, DE, and ME)

Parameter Control Effect of EtOH Effect of EtOH+H. scoparia extracts

HE DE ME

RBC (10

6

/mm

3

) 6.83±1.603 6.91±1.431 6.79±1.714 6.53±1.226 6.69±1.492

WBC (10

3

/mm

3

) 3.25±0.126 4.12±0.117* 3.47±0.167** 3.28±0.212** 3.37±0.124**

Hematocrit 0.414±0.01 0.408±0.012 0.395±0.014 0.420±0.016 0.418±0.008

Data represent mean±SEM of six rats. Symbols represent statistical significance

*P<0.05, when compared with control group; **P <0.05, when compared with ethanol group

Table 5 Biochemical indicators of liver function in serum of rats after chronic ethanol administration injected with or without H.

scoparia extracts

Parameter Control Effect of EtOH Effect of EtOH+H. scoparia extracts

HE DE ME

AST (IU/L) 114.50±3.12 192.16±5.49* 185.33±4.58* 170.33±6.91*

,

** 122.83±4.10***

ALT (IU/L) 53.66 ±2.80 96.50±2.66* 98.83±4.11* 84.83±3.45* 46.66±2.49***

ALP (IU/L) 186.16±4.62 260.83±4.49* 254.83±3.36* 249.33±3.12* 191.00±4.27***

Data represent mean±SEM of six rats. Symbols represent statistical significance

AST aspartate aminotransferase, ALT alanine aminotransferase, ALP alkaline phosph atase

*P<0.05 when compared with control group; **P<0.05, ***P<0.001, when compared with ethanol group

Hepatoprotective potential of H. scoparia 233

severity was much less when seen in sections treated

with ME (200 mg/kg) and was comparable to control.

The above results demonstrate that hepatoprotective

effect of plant extract may be due to inhibitory effect

on free radical formation.

In addition, to maintain redox homeostasis, aerobic

cells have developed an antioxidant system implicat-

ing phase II detoxification genes [23]. These genes

involve NAD(P)H, glutathione S-transferase, glutathi-

one peroxidase, and heme oxygenase-1. The transcrip-

tional factor nuclear factor E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2)

regulates the expression of antioxidant phase II

genes and contributes to the preserv ation of redox

homeostasis and cell viability in response to oxi-

dants damage. As a matter of fact, Nrf2 regulates

the expression of glutathione peroxidase and pro-

tects against hydrogen peroxide-induced glutathione

depletion [24]. When cells wer e exposed to reactive

oxygen species, Nrf2 is released from the cytoplas-

mic complex with keap1, leading to its translocation

to the nucleus, where Nrf2 activates transcription of

antioxidant phase II genes [20], such as glutathione

peroxidase. Salazar has shown that active GSK-3β

phosphorylates Nrf2 resulting in its exclusion from

the nucleus [24].

Superoxide dismutase, catalase, and glutathione

peroxida se ac tivities decreas ed sig nificantly in

ethanol-treated rats, which is in agreement with

previous data demonstrating a decrease in antioxi-

dant defense activities in rat liver exposed to eth-

anol [31]. Treatment with plant extracts showed

that only GPx activity was corrected in the group

receiving ME. However, SOD and CAT activities

did not move, compared to EtOH group, following

treatment with plant extract (HE, DE, and ME),

reflecting that the protective effect of ME involves

the GPx pathway without adjusting SOD and CAT

activities. Therewith, the decrease in TBARS lev-

els in animals receiving ME with respect to the

controls is strongly related to the standardization

ofGPxactivityinliver.

The significant increase in GPx content in the

liver, after ME treatment, suggests an antioxidant

activity of H. scoparia leaves extracts. Thus, it can

be concluded that a possible mechanism of hepato-

protective activity of H. scoparia leaves may be

Fig. 2 Effect of ethanol-treatment (for 4 weeks) with or without

H. scoparia extracts (HE, DE, and ME) on lipid peroxidation and

antioxidant enzymes activities in liver. a Thiobarbituric acid-

reacting substances (TBARS); b superoxide dismutase activity,

SOD represents the amount of enzyme that inhibits the oxidation

ofNBTby50%/mgprotein;c catalase activity (CAT; μmol H

2

O

2

/

min/mg protein); d glutathione peroxidase activity (GPx; μmol

GSH/min/mg protein). Values are the mean±SEM (n0 6. **P<

0.01, significantly different from control group; *P<0.05, signif-

icantly different from control group.

++

P<0.01, significantly dif-

ferent from ethanol-treated group;

+

P<0.05, significantly different

from ethanol-treated group)

234 E. Bourogaa et al.

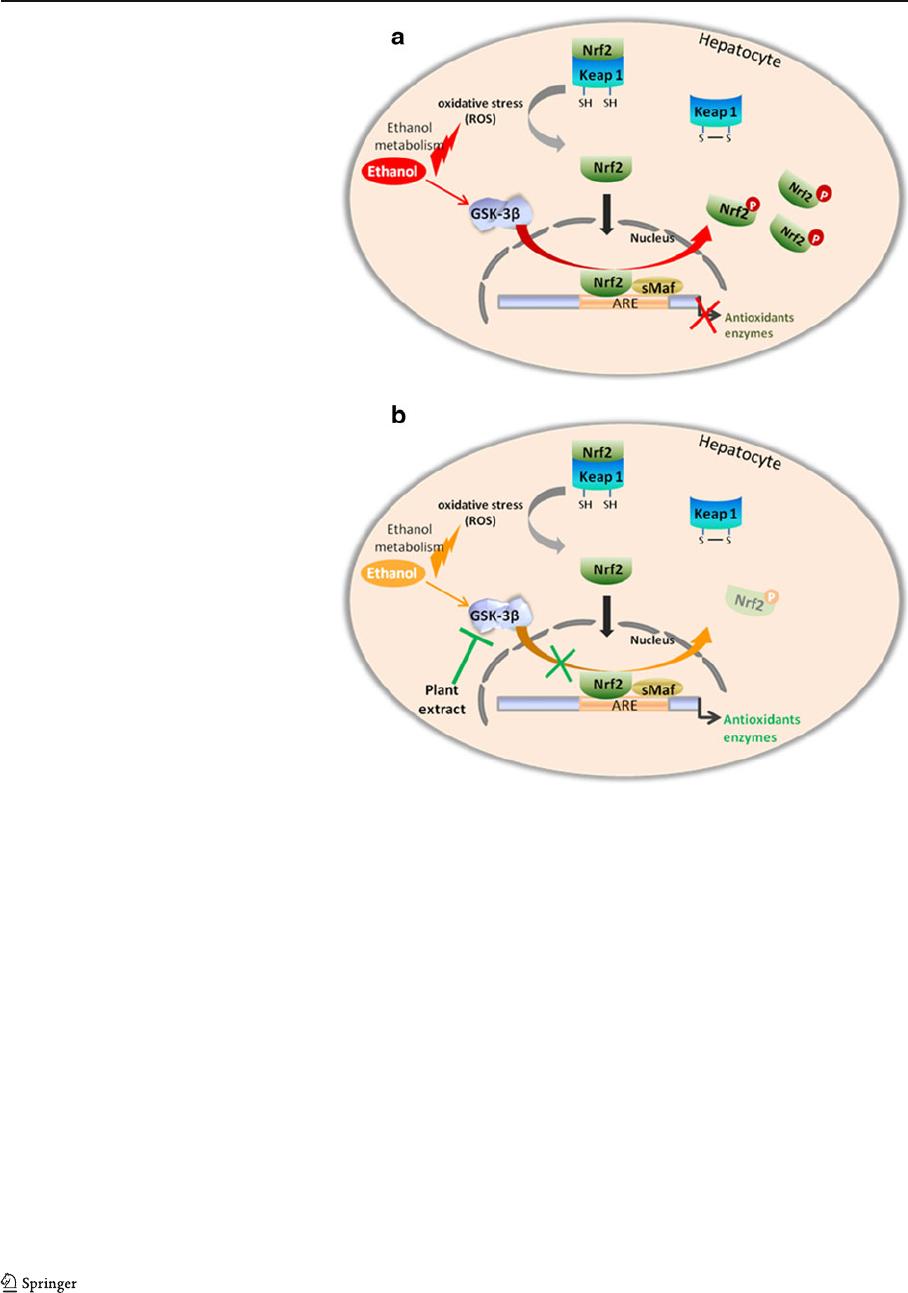

due to the inactivation of GSK-3β after plant ex-

tract (ME) treatment. Once GSK-3β is inactivated,

Nrf2 is not phosphorylated, not excluded from the

nucleus, and therefore, they induce the expression

Fig. 4 Hepatic immunoblot

analysis of GSK-3β and

phospho-Serine

9

GSK-3β

(P-Ser9 GSK-3β): Ethanol

treatment induces GSK-3β

expression. This increase

was bloqued in liver of rats

receiving H. scoparia

extracts (HE, DE, and ME).

GSK-3β was immunopreci-

pitated with monoclonal anti-

GSK-3β and Ser

9

GSK-3β

phosphorylation was deter-

mined by immunoblot analy-

sis with phospho-specific

antibody

Fig. 3 a Liver sections of

normal control rats showing

normal hepatic cells. b Liver

section of ethanol treated

rats showing: vacuolization

and ballooning degenera-

tion. c– e Liver sections of

ethanol-fed rats treated with

HE, DE, and ME, respec-

tively (V vacuolization, B

ballooning) (HE, ×200)

Hepatoprotective potential of H. scoparia 235

of glutathione peroxidase (Fig. 5). This antioxidant

activity may be attributable to the presence of phe-

nolic compounds in methanolic extract, which pre-

sented a potent antiradical activity in comparison

with ascorbic acid.

In fact, we previously isolated from H. scoparia

polar extract some phenolic alkaloids (N-methylisosal-

soline, 1-methylisosalsolinol, and dopamine) and fla-

vonoids (quercetin, isorhamnetin, and quercetin 3-O-

robinobioside) [14].

Our results confirm the relationship between the

glycogen synthase kinase and glutathione peroxi-

dase. Immunoblot analysis showed an activation of

GSK-3β in liver of ethanol treated animals. These

data were in agreement with those of Shin et al.

[27], who showed that H

2

O

2

activates GSK-3β.

The activation of GSK-3β mediates phosphorylation

of Nrf2 and its exclusion from the nucleus, which

was marked by a decrease in GPx activity

(Fig. 5a). GPx gene silencing was prevented by

methanolic extract of H. scoparia leaves adminis-

tered simultaneously with ethanol treatment. This

could be explained by the inactivation of GSK-3 β

after treatment with the extract.

Conclusion

The present study has proved that the hepatoprotective

action of methanolic extract of H. scoparia, the most

effective among the ones tested, may be due to its

antioxidant activity as indicated by the protection

against inc reased lipid peroxidation and maintained

GPx activity.

Fig. 5 Possible mechanisms

for the antioxidative effect

of methanolic extract in liver

cells. a Inactivation of

antioxidant enzymes after

ethanol administration. b

Protective ef fect of methanolic

extract

236 E. Bourogaa et al.