Editorial

A COVID-19 Airway Management Innovation with Pragmatic Efficacy

Evaluation: The Patient Particle Containment Chamber

LAUREN M. MALONEY ,

1,2

ARIEL H. YANG

,

2,3

RUDOLPH A. PRINCI,

1

ALEXANDER J. EICHERT,

2

DANIELLA R. HE

´

BERT,

4

TAELYN V. KUPEC,

7

ALEXANDER E. MERTZ,

5

ROMAN VASYLTSIV,

2,8

THEA M. VIJAYA KUMAR,

4

GRIFFIN J. WALKER,

6

EDDER J. PERALTA,

1

JASON L. HOFFMAN,

1

WEI YIN,

2

and CHRISTOPHER R. PAGE

2,9

1

Department of Emergency Medicine, Stony Brook University Hospital, Stony Brook, NY, USA;

2

Department of Biomedical

Engineering, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, NY, USA;

3

Renaissance School of Medicine at Stony Brook University,

Stony Brook, NY, USA;

4

Department of Mechanical Engineering, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, NY, USA;

5

School of

Health Technology and Management, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, NY, USA;

6

Department of Technology and

Society, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, NY, USA;

7

Department of Psychology, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook,

NY, USA;

8

Department of Physics and Astronomy, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, NY, USA; and

9

Department of

Anesthesiology, Stony Brook University Hospital, Stony Brook, NY, USA

(Received 11 August 2020; accepted 17 August 2020)

Associate Editor Dan Elson oversaw the review of this article.

Abstract—The unique resource constraints, urgency, and

virulence of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic has

sparked immense innovation in the development of barrier

devices to protect healthcare providers from infectious

airborne particles generated by patients during airway

management interventions. Of the existing devices, all have

shortcomings which render them ineffective and impractical

in out-of-hospital environments. Therefore, we propose a

new design for such a device, along with a pragmatic

evaluation of its efficacy. Must-have criteria for the device

included: reduction of aerosol transmission by at least 90%

as measured by pragmatic testing; construction from readily

available, inexpensive materials; easy to clean; and compat-

ibility with common EMS stretchers. The Patient Particle

Containment Chamber (PPCC) consists of a standard

shower liner draped over a modified octagonal PVC pipe

frame and secured with binder clips. 3D printed sleeve

portals were used to secure plastic sleeves to the shower liner

wall. A weighted tube sealed the exterior base of the chamber

with the contours of the patient’s body and stretcher. Upon

testing, the PPCC contained 99% of spray-paint particles

sprayed over a 90s period. Overall, the PPCC provides a

compact, affordable option that can be used in both the in-

hospital and out-of-hospital environments.

Keywords—COVID-19, Aerosol, Intubation, Airway, Per-

sonal protective equipment, Emergency medical services.

ABBREVIATIONS

COVID-19 Coronavirus disease 2019

EMS Emergency medical services

HEPA High efficiency particulate air

NIOSH National Institute of Occupational

Safety and Health

PPCC Patient Particle Containment

Chamber

PPE Personal protective equipment

PVC Polyvinyl chloride

SARS-CoV-2 Severe acute respiratory syndrome

corona virus 2

Address correspondence to Lauren M. Maloney, Department of

Emergency Medicine, Stony Brook University Hospital, Stony

Brook, NY, USA. Electronic mail: lauren.maloney@

stonybrookmedicine.edu

Annals of Biomedical Engineering (Ó 2020)

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10439-020-02599-6

BIOMEDICAL

ENGINEERING

SOCIETY

Ó 2020 The Author(s)

INTRODUCTION

Recent evidence has shown that severe acute respi-

ratory syndrome corona virus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) may

remain infectious as an aerosol for at least 3 h.

29

Al-

though the exact mode of SARS-CoV-2 transmission

remains is still under investigation, it is likely that

airborne transmission via aerosols and droplets is a

significant factor in human-to-human spread.

31

Given

that the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused

by SARS-CoV-2 is predominantly a pulmonary dis-

ease,

1,22

it follows that moderately to severely ill

patients will often require some form of airway inter-

vention.

6,23

Secretions coming from the upper and

lower airways have been found to contain high viral

loads.

24,30

Therefore, aerosol-generating airway inter-

ventions such as ventilations with a bag-valve mask,

endotracheal intubation and extubation, as well as

tracheal suctioning place healthcare providers at

increased risk for viral exposure.

7,11,26

This risk of

exposure is further complicated by a widespread con-

cern about the availability of and access to appropriate

personal protective equipment (PPE).

3,25

Therefore,

innovative approaches to protect healthcare providers

from aerosols and droplets gen erated during airway

interventions is an integral component of limiting the

spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

In late March 2020, Taiwanese anesthesiologist Dr.

Lai Hisen-Yung began to develop the Aerosol Box: a

transparent acrylic box to be placed over a patient,

with an open side facing the chest and two holes

through which a healthcare provider can insert their

hands in order to perform airway interventions.

13,15,27

A simulated patient cough using compressed oxygen to

explode a dye-containing balloon suggested that

without the Aerosol Box, dye dro plets were visible on

the healthcare provider’s face, torso, and floor, com-

pared to just the healthcare provider’s hands and

forearms with the Aerosol Box in place.

8

This barrier

device was rapidly adopted by hospitals internationally

even wi thout adequate evidence about its efficacy. This

was due in large part to dissemination via social media

sharing.

10,27

However, difficulties with the Aerosol Box were

soon realized. It was found to be restrictive, can cre-

ate tears in healthcare provider s’ PPE, interferes with

the use of a video laryngoscope, an d is subject to glare

from overhead lighting. In addition, it has a very

limited ability to adapt to healthcare provider height or

to patient body habitus.

8,10,18,28

Additional obstacles

include managing the device’s weight and bulkiness

during transport, securing the device to the bed espe-

cially if the head is elevated, and proper decontami-

nation and storage procedures.

10

Although multiple

iterations of the Aerosol Box have been devised

addressing some of these concerns, very limited overall

data exists to quantify its ability to protect staff present

in the patient’s room.

The use of barrier devices to limit airborne trans-

mission during airway interventions so far has been

limited to in-hospital sett ings. Many of the critiques of

the Aerosol Box would likely be amplified in an out-of-

hospital environment. This is due to the constraints of

ambulance stretcher dimensions, portability, and

storage. Additionally, the patient care compartment of

an ambulance is generally much smaller than a critical

care procedure room in an Emergency Department,

operating room, or inpatient hospital room. Perform-

ing airway interventions for patients suspected of

having coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in an

ambulance in accordance with current consensus rec-

ommendations

7,11

is further complicated by patient

compartments rarely being equipped to induce nega-

tive-pressure, and the lack of national standards for

ambulance ventilation systems in the United States.

20

Our primary objective was to create a barrier device

with the ability to reduce transmission of airborne

particles generated during airway interventions that is

portable and could be assembled from commonly

available components that are unlikely to be in short

supply during the pandemic. Critical design criteria for

the device included the reduction of transmission of

airborne particles by at least 90% as measured by

pragmatic testing; construction using materials outside

of the traditional hospital supply chain which can be

readily obtained on a limited budget and timeline; any

reusable components are easy to clean; and dimensions

allowing for use within the limit ed space of commonly

used EMS stretchers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Setting

This device was created and pragmatically tested at

Stony Brook University Hospital, in Stony Brook,

NY, USA. Stony Brook University Hospital is a sub-

urban, academic tertiary care center, located on a

shared campus with Stony Brook University.

Patient Particle Containment Chamber (PPCC)

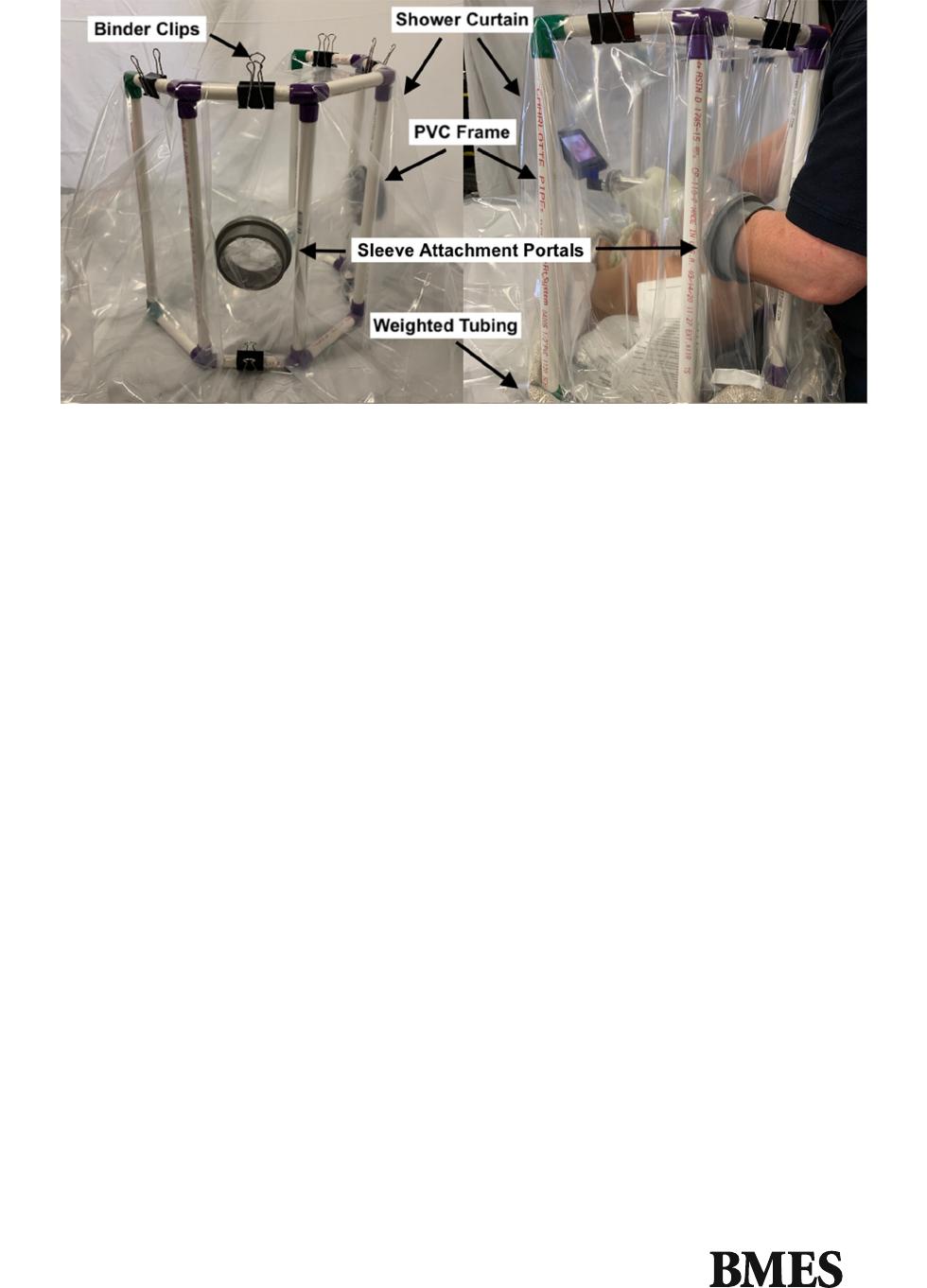

Supplementary Material A describes the assembly

process in detail. Briefly, as illustrated in Fig. 1, the

PPCC frame was constructed from ½ in. PVC pipes

and PVC fittings (Fig. 1). A clear shower liner was

draped over the frame and secured in place using 2 in.

binder clips. 3D printed portals were used to mount

BIOMEDICAL

ENGINEERING

SOCIETY

MALONEY et al.

plastic sleeves onto the shower liner wall. Seven-inch

diameter 3mil poly tubing was used for the plastic

sleeve material. A weighted tube was draped along the

exterior base of the chamber and secured in place using

double sided tape.

Contamination Evident Chamber

A cube-shaped support structure was assem bled

using ½ in. 92 in. 948 in. poplar boards. The cube

was lined using 48 in. wide easel paper, creating the

Contamination Evident Chamber.

An investigator placed a gowned arm into the

Containment Evident Chamber via a small hole cut in

the easel paper and sprayed a can of black spray paint

within the chamber in all directions for 90 s. Paint was

visually seen on all six surfaces after the 90 s. The paint

was allowed to dry. This served as the control to

compare to the performance of the PPCC to.

The paper of the chamber was changed, and the

PPCC was placed within it. An identical can of black

spray paint was placed inside the PPCC and was

sprayed in all directions for 90 s by the same investi-

gator as before. The paint was allowed to dry.

Measurements

After being cut into 8.5 9 11’’ sections, the easel

paper was scanned into a digital image. ImageJ soft-

ware (NIH, Bethesda, MD) was then used to determine

the surface area covered by black paint. The total area

of paint coverage was measured in terms of pixels and

then converted to units of square inches using the

appropriate conversion factors.

RESULTS

Without the PPCC in place, the total surface area of

the Contamination Evident Chamber covered by black

paint was 2312 square inches. With the PPCC in place,

less than 1 square inch of surface area outside of the

PPCC was covered by black paint, and it was limited

to only the floor surface of the Contamination Evident

Chamber. The area of the Contamination Evident

Chamber underneath the PPCC, as well as the inner

surfaces of the walls of the PPCC, were completely

covered in black paint. The exact margins of the PPCC

were difficult to ascertain, as the folds of the shower

liner material draped onto the floor in an irregular

shape, as intended, and often in several layers. By

geometry, the PPCC frame covers 232 square inches of

the floor surface of the Contamination Evident

Chamber. Conservatively factoring in a possible 10%

additional surface area that may be covered by the

layers of shower liner, approximately 256 square inches

of the floor surface of the Contamination Evident

Chamber is covered by the PPCC. Reducing this area

from the total surface area of the Contamination

Evident Chamber covered in black paint without the

PPCC in place infers that 2,056 square inches of paint

covered area was outside the area encapsulated by the

PPCC. Therefore, the PPCC reduced the total surface

area of black paint in the Contamination Evident

Chamber by more than 99%.

The total cost per PPCC was $63.70. This fig ure in-

cludes the cost of shippi ng for products purchased

online, as well as the local sales tax of 8.6%. The cost

of the re-usable components was $52.18. The cost for

the single-use disposable components was $11.52. Of

FIGURE 1. The Patient Particle Containment Chamber with labeled components.

BIOMEDICAL

ENGINEERING

SOCIETY

COVID Patient Particle Containment Chamber

note, this does not include the cost of labor or the 3D

printing materials.

DISCUSSION

In response to the need for innovative ways to safely

perform airway interventions on patients with COV-

ID-19 in the setting of limited availability of personal

protective equipment, we designed a Patient Particle

Containment Chamber. The device was made from

readily available materials that are outside the tradi-

tional hospital supply chain. Total materials cost was

approximately $60. In comparison, commercially-

made solutions available for online purchase range in

cost from $60-270 (excluding tax and shipping costs),

and are dependent upon specific companies’ material

production and their supply availability.

16,17,19,27

Pragmatic testing of the chamber using a can of black

spray paint suggests that it is at least 99% effective in

reducing the transmission of small airborne particles.

The creation and subsequent almost immediate

world-wide adoption of the Aerosol Chamber was a

clear demonstation of the power of idea dissemination

through social media. However, the wildfire spread of

the device was followed by abrupt critiques about its

functionality, illustrating the cautionary tale proposed

by Duggan et al., for which they proposed the term

‘‘MacGyver bias.’’

12

The MacGyver bias is ‘‘the

inherent attraction of our own personal improvised

devices. This leads to a tendency to hold them in high

regard despite the relative absence of evidence for their

efficacy.’’

12

While necessity, especially when faced with

a highly contagious pandemic, may very well be the

mother of all invention, it is crucial that thought is

given to the determination of whether or not the device

does indeed do what is intended. Homemade devices

may come from a lack of existence of or lack of access

to a suitable commercially-available device. In such

cases, it is important to ponder how and if an inno-

vative solution would have undergone iterative chan-

ges in order to meet regulatory safety standar ds. Given

the speed with which COVID-19 traversed the globe,

traditional innovation timelines have been markedly

shortened. Adding to this, has been disruption of

hospital supply chains, leading to rapid depletion of

PPE. Furthermore, well-intentioned clinicians creating

these temporary solutions may lack a background in

the medical device innovation process. This may in-

crease the possibility of oversights in areas including

safety mechanisms, material selection, design toler-

ance, and product testing.

While the pragmatic testing of our proposed

chamber in reduction of airborne particle transmission

would certainly not conform to NIOSH standards, we

believe using a can of black spray paint is a reasonable

demonstration of efficacy. Reports suggest that air-

borne particles generated by standard spray paint cans

are of a size comparable to that which is necessary to

be defined as an infectious aerosol particle.

14,21

Fur-

thermore, this technique for testing can be easily

replicated by others if they would like to evaluate the

efficacy of their own de vices for a cost of less than $5.

Quantitative image analysis suggested that the de-

vice was able to prevent almost all simulated aero-

solized particles from leaving the device. Existing

published descriptions of attempts to evaluate how

useful barrier devices are at containing airborne par-

ticles have been limited to a qualitative description of

fluorescent dy e splatter patterns

8

and a video anlysis of

white vapor clouds flowing out of the Aerosol Box.

28

A

quantitative approach was described in the evaluat ion

of the utilit y of a constant flow canopy, a flexible

polyethylene canopy that is placed over the head and

upper thorax of pa tient while in a hospital bed which

contains a fan filtering unit and HEPA filter.

2

How-

ever, this device is not designed to allow an y sort of

airway intervention, but rather could limit the ambient

release of aerosols from patients undergoing noninva-

sive ventilation support. As smoke was piped under the

canopy, the face velocity and direction of the smoke

movement was determined, while photometry was used

to evaluate the integrity of the HEPA filter.

2

A single simulation-based study has been published

evaluating the impact of two generations of Aerosol

Boxes on sim ulated end otracheal intubation by anes-

thesiologists; however, it was not structured to evalu-

ate the efficacy of such devices on reducing airborne

particle exposure to clinicians.

5

It was found that with

the Aerosol Box in place, anesthesiologists took longer

to intubate, had fewer successful first attempts,

increased provider cognitive load , and increased pro-

vider discomfort during the procedure. Most con-

cerningly, was the number of breaches in PPE that

resulted from the gown getting stuck or torn in the arm

holes of the Aerosol Box.

5

Having already undergone several iterations, we

have shown that our device successfully addresses

many of these issues. The Patient Particle Containment

Chamber provides plenty of space for unhindered

airway interventions such as using a handheld video

laryngoscope or airway adjuncts. When not in use, it

can be collapsed and stored easily. Reusable compo-

nents are easy to clean and disinfect. Additionally, it is

unlikely that gowns will be torn given the mobile

nature of the sleeve attachment portals. Although ac-

cess to a 3D printer is necessary to create the sleeve

attachment portals, news reports sugge st access to this

equipment is more univers al than ever before, partic-

ularly through local libraries and high schools.

4,9

BIOMEDICAL

ENGINEERING

SOCIETY

MALONEY et al.

Future iterations of the Patient Particle Contain-

ment Chamber will need to address several design

elements. First, in order to consider leaving this device

in place for extended periods of time to allow for

longer airway interventions such as a nebulized medi-

cation, hourly tracheal suctioning, or extubation,

determination of a safe time period that the device can

be used before ambient oxygen is depleted or carbon

dioxide accumulates must be made. A system similar

to the fan filtering unit and HEPA filter described by

Adir et al. could be considered in order to better

control air and particle flow.

2

This may also help

mitigate dangerous diffusion of aerosols contained

within the chamber into the surrounding air once the

device is removed. Alternatively, we have created a

miniature version of the sleeve attachment portal

which would allow for ventilator tubing to pass

through the chamber. These could be configured to

allow for a bag -valve mask to be attached to the

chamber to introduce supplemental oxygen, as well as

adapted to allow for any outflow to be filtered. Several

components of the chamber could be prepared in ad-

vance in order to shorten the assembly time, and it may

be useful to include elastic cord within the top and

bottom partial octagons of the frame to allow for

faster frame assembly. Availability of completely pre-

fabricated fittings may help to remove the need to glue

pieces together. Specific to its out-of-hospital use, the

chamber frame fits well on the top of the most com-

mon EMS stretchers, though additional stability could

be added by using a clamp to hold the bottom of the

frame to the stretcher mattress. This could reduce the

potential for the device to topple off of the patient

during transport or when the head of the stretcher is

raised. Finally, the chamber needs to undergo formal

compliance testing, similar to what is done for labo-

ratory ventilator hoods, before its efficacy can be

reported with precision.

This study was limited to a single attempt made to

pragmatically quantify the amount of black spray

paint that was apparent on the inner surfaces of a 4-

foot cube with and without the chamber in place. The

data that we are able to report is limited due to a lack

of ability to determine the exact edge of the enclosure.

The irregular, multilayered way the shower liner was

wrapped around the weighted tube did not allow for

clearly defined boundaries. The initial iteration used a

6 foot long dishwasher tube filled with water and oc-

cluded at each end as the weighted tube; while it ap-

peared to work, later iterations using pellet-filled 2 inch

wide 2 Mil poly tubing instead offered more compli-

ance across surface contours and easier use.

The current COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated

the lack of devices available to ensure provider safety

during airway interven tions. The device described

provides a promising solution to help protect both

hospital and out-of-hospital providers during airway

interventions. In addition, the design of the Patient

Particle Containment Chamber prioritizes the use of

readily accessible and economically affordable parts in

order to avoid contributing to a shortage of hospital

equipment during surges of patients. While current

constraints prevent the device from being formally

tested, initial pragmatic evaluation using airborne

particle simulation and imaging analysis yields highly

promising results. Although the device may not solve

all current concerns about healthcare provider safety

against respiratory viral infections, the PPCC provides

an additional, more versatile option to help limit

transmission of SARS-CoV-2 during high risk airway

interventions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project was funded by a grant from the 2019–

2020 State University of New York Research Seed

Grant Program, RFP #20-03-COVID, awarded to

Drs. Maloney, Page and Yin. The authors have no

additional financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

Additionally, the authors would like acknowledge the

efforts of undergraduate students Blerta Zeqiri, Andy

La and Hao Li.

OPEN ACCESS

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits

use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction

in any medium or format, as long as you give appro-

priate credit to the original author(s) and the source,

provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and

indicate if changes were made. The images or other

third party material in this article are included in the

article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated

otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is

not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence

and your intended use is not permitted by statutory

regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need

to obtain permission directly from the copyright

holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://crea

tivecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

FUNDING

Funding was provided by Research Foundation for

the State University of New York (Grant Number

1160436).

BIOMEDICAL

ENGINEERING

SOCIETY

COVID Patient Particle Containment Chamber

ELECTRONIC SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

The online version of this article (https://doi.org/10.

1007/s10439-020-02599-6) contains supplementary

material, which is available to authorized users.

REFERENCES

1

Ackermann, M., S. E. Verleden, M. Kuehnel, et al. Pul-

monary vascular endothelialitis, thrombosis, and angio-

genesis in COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 383(2):120–128,

2020.

2

Adir, Y., O. Segol, D. Kompaniets, et al. COVID-19:

minimising risk to healthcare workers during aerosol-pro-

ducing respiratory therapy using an innovative constant

flow canopy. Eur. Resp. J. 55(5):1, 2020.

3

Artenstein, A. W. In pursuit of PPE. N. Engl. J. Med.

382(18):e46, 2020.

4

Balzer, C. Using 3D to make PPE: library resources help

create much-needed face shields. American Libraries Ma-

gazine.

5

Begley, J. L., K. E. Lavery, C. P. Nickson, D. J. Brewster.

The aerosol box for intubation in coronavirus disease 2019

patients: an in situ simulation crossover study. Anaesthe-

sia.n/a(n/a).

6

Bhatraju, P. K., B. J. Ghassemieh, M. Nichols, et al.

COVID-19 in critically ill patients in the seattle region -

case series. N. Engl. J. Med. 382(21):2012–2022, 2020.

7

Brewster, D. J., N. Chrimes, T. B. Do, et al. Consensus

statement: safe airway society principles of airway man-

agement and tracheal intubation specific to the COVID-19

adult patient group. Med. J. Aust. 212(10):472–481, 2020.

8

Canelli, R., C. W. Connor, M. Gonzalez, A. Nozari, and

R. Ortega. Barrier enclosure during endotracheal intuba-

tion. N. Engl. J. Med. 382(20):1957–1958, 2020.

9

Cardine, S. Good Samaritans borrow unused school

machines to 3D-print coronavirus masks, shields. Los

Angeles Times.

10

Chan, A. Should we use an ‘‘aerosol box’’ for intubation?

2020. https://litfl.com/should-we-use-an-aerosol-box-for-in

tubation/. Accessed 22 June 2020.

11

Cook, T. M., K. El-Boghdadly, B. McGuire, A. F.

McNarry, A. Patel, and A. Higgs. Consensus guidelines for

managing the airway in patients with COVID-19: Guide-

lines from the Difficult Airway Society, the Association of

Anaesthetists the Intensive Care Society, the Faculty of

Intensive Care Medicine and the Royal College of Anaes-

thetists. Anaesthesia. 75(6):785–799, 2020.

12

Duggan, L. V., S. D. Marshall, J. Scott, P. G. Brindley, and

H. P. Grocott. The MacGyver bias and attraction of

homemade devices in healthcare. Can. J. Anaesth.

66(7):757–761, 2019.

13

Everington, K. Taiwanese doctor invents device to protect

US doctors against coronavirus. Taiwan News. 23 Mar

2020.

14

Go

¨

hler, D., and M. Stintz. Granulometric characterization

of airborne particulate release during spray application of

nanoparticle-doped coatings. J. Nanoparticle Res.

16(8):2520, 2014.

15

Hsu, S. H., H. Y. Lai, F. Zabaneh, F. N. Masud. Aerosol

containment box to the rescue: extra protection for the

front line. Emerg. Med. J. 2020.

16

Intubation Box. https://www.vacep.org/intubationbox.

Accessed 22 June 2020.

17

IntubationPod. https://utwpods.com/products/intubation

pod. Accessed 24 June 2020.

18

Kearsley, R. Intubation boxes for managing the airway in

patients with COVID-19. Anaesthesia. 75(7):969, 2020.

19

Leyva Moraga, F. A., E. Leyva Moraga, F. Leyva Moraga,

et al. Aerosol box, an operating room security measure in

COVID-19 pandemic. World J. Surg. 44(7):2049–2050,

2020.

20

Lindsley, W. G., F. M. Blachere, T. L. McClelland, et al.

Efficacy of an ambulance ventilation system in reducing

EMS worker exposure to airborne particles from a patient

cough aerosol simulator. J. Occup. Environ. Hygiene

16(12):804–816, 2019.

21

Lindsley, W. G., J. S. Reynolds, J. V. Szalajda, J. D. Noti,

and D. H. Beezhold. A cough aerosol simulator for the

study of disease transmission by human cough-generated

aerosols. Aerosol. Sci. Technol. 47(8):937–944, 2013.

22

Madabhavi, I., M. Sarkar, N. Kadakol. COVID-19: a re-

view. Monaldi archives for chest disease = Archivio Mon-

aldi per le malattie del torace. 2020;90(2).

23

Meng, L., H. Qiu, L. Wan, et al. Intubation and ventilation

amid the COVID-19 outbreak: Wuhan’s experience. Anes-

thesiology. 132(6):1317–1332, 2020.

24

Setti, L., F. Passarini, G. De Gennaro, et al. Airborne

transmission route of COVID-19: why 2 meters/6 feet of

inter-personal distance could not be enough. Int. J. Envi-

ron. Res. Public Health 2020;17(8).

25

Shanafelt, T., J. Ripp, M. Trockel. Understanding and

addressing sources of anxiety among health care profes-

sionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA 2020.

26

Tran, K., K. Cimon, M. Severn, C. L. Pessoa-Silva, and J.

Conly. Aerosol generating procedures and risk of trans-

mission of acute respiratory infections to healthcare

workers: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. 7(4):e35797,

2012.

27

Tseng, J. Y., and H. Y. Lai. Protecting against COVID-19

aerosol infection during intubation. J. Chin. Med. Assoc.

83(6):582, 2020.

28

Turer, D. C., B. H. Jason. Intubation boxes: an extra layer

of safety or a false sense of security? STAT. 2020.

29

van Doremalen, N., T. Bushmaker, D. H. Morris, et al.

Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared

with SARS-CoV-1. N. Engl. J. Med. 382(16):1564–1567,

2020.

30

Wang, W., Y. Xu, R. Gao, et al. Detection of SARS-CoV-2

in different types of clinical specimens. JAMA.

323(18):1843–1844, 2020.

31

Zhang, R., Y. Li, A. L. Zhang, Y. Wang, and M. J. Mo-

lina. Identifying airborne transmission as the dominant

route for the spread of COVID-19. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.

USA 117(26):14857–14863, 2020.

Publisher’s Note Springer Nature remains neutral with re-

gard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institu-

tional affiliations.

BIOMEDICAL

ENGINEERING

SOCIETY

MALONEY et al.