CLINICAL INVESTIGATION INTERVENTIONAL ONCOLOGY

Short-term Safety and Quality of Life Outcomes Following

Radioembolization in Primary and Secondary Liver Tumours:

a Multi-centre Analysis of 200 Patients in France

Romaric Loffroy

1

•

Maxime Ronot

2

•

Michel Greget

3

•

Antoine Bouvier

4

•

Charles Mastier

5

•

Christian Sengel

6

•

Lambros Tselikas

7

•

Dirk Arnold

8

•

Geert Maleux

9

•

Jean-Pierre Pelage

10

•

Olivier Pellerin

11

•

Bora Peynircioglu

12

•

Bruno Sangro

13

•

Niklaus Schaefer

14

•

Marı

´

a Urda

´

niz

15

•

Nathalie Kaufmann

15

•

Jose

´

Ignacio Bilbao

16

•

Thomas Helmberger

17

•

Vale

´

rie Vilgrain

2

•

On behalf of the CIRT-

FR Principal Investigators

Received: 16 July 2020 / Accepted: 2 September 2020

Ó The Author(s) 2020

Abstract

Purpose Radioembolization has emerged as a treatment

modality for patients with primary and secondary liver

tumours. This observational study CIRT-FR (CIRSE Reg-

istry for SIR-Spheres Therapy in France) aims to evaluate

real-life clinical practice on all patients treated with

transarterial radioembolization (TARE) using SIR-Spheres

yttrium-90 resin microspheres in France. In this interim

analysis, safety and quality of life data are presented. Final

results of the study, including secondary effectiveness

outcomes, will be published later. Overall, CIRT-FR is

aiming to support French authorities in the decision making

on reimbursement considerations for this treatment.

Methods Data on patients enrolled in CIRT-FR from

August 2017 to October 2019 were analysed. The interim

analysis describes clinical practice, baseline characteristics,

safety (adverse events according to CTCTAE 4.03) and

quality of life (according to EORTC QLQ C30 and HCC

module) aspects after TARE.

Results This cohort included 200 patients with hepatocel-

lular carcinoma (114), metastatic colorectal cancer

(mCRC; 38) and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (33)

amongst others (15). TARE was predominantly assigned as

a palliative treatment (79%). 12% of patients experienced

at least one adverse event in the 30 days following treat-

ment; 30-day mortality was 1%. Overall, global health

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this

article (https://doi.org/10.1007/s00270-020-02643-x) contains sup-

plementary material, which is available to authorized users.

& Nathalie Kaufmann

1

Department of Vascular and Interventional Radiology,

Image-Guided Therapy Center, CHU Dijon Bourgogne,

Franc¸ois-Mitterrand University Hospital, 14 Rue Gaffarel,

21000 Dijon, France

2

Department of Radiology, Universite

´

de Paris, Ho

ˆ

pital

Beaujon APHP, and CRI, INSERM 1149, Paris, France

3

Service d’Imagerie interventionnelle, Ho

ˆ

pitaux Universitaires

de Strasbourg, 1 Avenue Moliere, 67000 Strasbourg, France

4

Department of Radiology, Angers University Hospital, 4 Rue

Larrey, 49933 Angers, France

5

Interventional Radiology, Centre Le

´

on Be

´

rard, 28 Prom. Le

´

a

Et Napole

´

on Bullukian, 69008 Lyon, France

6

Interventional Radiology, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de

Grenoble, Boulevard de la Chantourne, 38100 Grenoble,

France

7

Interventional Radiology, De

´

partement d’anesthe

´

sie

Chirurgie et Interventionel (DACI), Gustave Roussy,

Universite

´

Paris-Saclay, Villejuif, France

8

Oncology and Hematology, Asklepios Tumorzentrum

Hamburg, AK Altona, Paul-Ehrlich-Str. 1, 22763 Hamburg,

Germany

9

Radiology, Universitair Ziekenhuis Leuven, Herestraat 49,

3000 Leuven, Belgium

10

Department of Diagnostic Imaging and Interventional

Radiology, Caen University and Medical Center, avenue de

la Cote de Nacre, 14033 Caen, France

11

Interventional Radiology Department, Ho

ˆ

pital Europe

´

en

Georges Pompidou, 20 rue Leblanc, 75015 Paris, France

12

Department of Radiology, School of Medicine, Hacettepe

University, Sihhiye Campus, 06100 Ankara, Turkey

13

Clı

´

nica Universidad de Navarra, IDISNA and CIBEREHD,

Liver Unit, Avda. Pio XII 36, 31008 Pamplona, Spain

123

Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00270-020-02643-x

score remained stable between baseline (66.7%), treatment

(62.5%) and the first follow-up (66.7%).

Conclusion This interim analysis demonstrates that data

regarding safety and quality of life generated by ran-

domised-controlled trials is reflected when assessing the

real-world application of TARE.

Trial Registration Clinical Trials.gov NCT03256994.

Keywords Radioembolization Transarterial

radioembolization Yttrium-90 SIR-spheres

Interim analysis SIRT

Introduction

Transarterial radioembolization (TARE), also known as

selective internal radiation therapy (SIRT), with SIR-

Spheres Y-90 resin microspheres, is an endovascular pro-

cedure included within the interventional oncologic arma-

mentarium to treat primary and secondary liver tumours

[1–7].

CIRT-FR (CIRSE Registry for SIR-Spheres Therapy in

France; NCT03256994) was developed as a France-only

adaptation of the pan-European, prospective observational

study CIRT (NCT02305459) [8]. While CIRT [9] had only

collected data from one French hospital, CIRT-FR was

open to all French centres and designed to exhaustively

include as many patients in France as possible. Under the

condition that the present study was conducted in order to

collect data on the real-life clinical application of TARE

with SIR-SpheresÒ in France, reimbursement for liver-

only metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) was granted for

5 years by the French national health authorities (Haute

Autorite

´

de Sante

´

, HAS) in March 2017.

1

In March 2019,

based on the results of the phase III randomized controlled

trials SARAH [10] and SIRveNIB [11], HAS extended

reimbursement for patients with intermediate or advanced

hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC

2

). Final data from this

observational study will support French authorities in the

decision making on reimbursement considerations for

TARE beyond 2022.

This publication is the 200-patient interim analysis of

the prospective, post-market, observational study CIRT-

FR, with the objective to report on patient characteristics,

treatment details as well as safety and health-related quality

of life.

The primary objective was to observe the real-life

clinical application of TARE with SIR-Spheres Y-90 resin

microspheres in the context of the patients’ continuum of

care (please refer to Table 1). Secondary objectives were to

assess safety, toxicity, quality of life, technical considera-

tions and diagnosis and treatment-related considerations,

such as intention of treatment, prior and post-TARE

interventional procedures and/or systemic therapy.

Methods

Study Design/Setting

Patients for this 200-patient interim analysis were enrolled

from 11 centres between August 2017 and October 2019,

and follow-up data were collected until June 2020. All

hospitals in France that had performed TARE with SIR-

Spheres or were preparing to perform their first treatment

were invited to participate. Hence, 31 sites were invited to

participate, of which 4 declined participation, 4 were in the

contracting process at the time of this analysis and 22 sites

participated. Data were monitored by CIRSE remotely

every 3 months to verify data quality and completion, and

to identify any issues with patient inclusion and data col-

lection. This study was performed in accordance with the

Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice

Guidelines and was approved by the CPP SUD-EST II

French Ethics Committee (N° ID-RCB: 2017-A01003-50).

Since this study is an offspring of the European observa-

tional study CIRT [9] and closely corresponds to its

methodology, please refer to the published methodology of

CIRT for a more detailed description of methods and

outcome measures [8].

14

Service de me

´

decine nucle

´

aire Et Imagerie mole

´

culaire,

Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Lausanne, Rue du

Bugnon 46, CH-1011 Lausanne, Switzerland

15

Clinical Research Department, Cardiovascular and

Interventional Radiological Society of Europe, Neutorgasse

9, 1010 Vienna, Austria

16

Interventional Radiology, Clı

´

nica Universidad de Navarra,

Avenida Pio XII, no 36, 31008 Pamplona, Spain

17

Department of Radiology, Neuroradiology and Minimal-

Invasive Therapy, Klinikum Bogenhausen, Englschalkinger

Str. 77, 81925 Munich, Germany

1

HAS (2015). Avis de la CNEDiMTS sur SIR-Spheres. Retrieved

March 2, 2017, from https://www.has-sante.fr/portail/jcms/c_

2023879/fr/sir-spheres

2

HAS (2018). Avis de la CNEDiMTS sur SIR-Spheres. Retrieved

October 7, 2019, from https://www.has-sante.fr/jcms/c_2896412/fr/

sir-spheres

R. Loffroy et al.: Short-term Safety and Quality of Life Outcomes...

123

Patients

Patients were required to be at least 18 years old and to

have primary or metastatic liver cancer intended to be

treated with TARE (using SIR-Spheres) and to have signed

an informed consent form. There were no further specified

inclusion or exclusion criteria. Since the aim of the study

was to capture all patients treated with SIR-Spheres in

France, patients included in other trials were permitted to

be enrolled. As a result, some intrahepatic cholangiocar-

cinoma patients of the present study were treated within the

SIRCCA trial (NCT 02807181), but there were no patients

in common with the European CIRT registry [9]. All

aspects related to treatment and follow-up were performed

at the discretion of the treating physicians. It was recom-

mended to perform follow-ups every 3 months, for a period

of at least 24 months.

Outcomes and Data Sources

The primary outcome was defined as the real-life clinical

application of TARE in order to assess at which stage of

the cancer continuum of care the therapy was utilised.

Secondary endpoints covered in this interim analysis were

safety data and health-related quality of life (HRQOL)

[12, 13]. For safety, adverse events (AE) and abnormal

laboratory findings were graded according to the Cancer

Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse

Events (CTCAE) v4.03. Adverse events were classified

into three main groups; peri-procedural AE (on the same

day of the treatment), AE within 30 days after treatment

and AE after more than 30 days after treatment.

HRQOL was assessed using the EORTC QLQ-C30

questionnaire, as well as the QLQ-HCC18 Module for

patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [14].

Questionnaires were to be filled before, within one week

after treatment and the first follow-up. Median first follow-

up was at 13 weeks (IQR = 3).

For the HRQOL analysis (according to version 3 of the

EORTC QLQ-C30 Scoring Manual (2001) and version 2 of

the EORTC QLQ-HCC18 Scoring Manual), only patients

with data available for all three timepoints (before treat-

ment, within one week after treatment, and the first follow-

up) were included, as a ‘‘per protocol’’ analysis. Scores for

global health, functionality and symptoms were calculated

by linearly transforming the mean of the respective raw

scores on a scale of 0 to 100. For the global health and the

functional score, a high score indicated high health and for

the symptoms and the HCC18 Module a low score indi-

cates few symptoms and better quality of life.

Bias

In order to reduce patient selection bias, participation in the

observational study was contractually required to be

offered to all patients with primary or secondary liver

tumours treated with TARE using SIR-Spheres. Further-

more, in order to assess patient coverage, case logs listing

the number of patients treated versus number of patients

actually enrolled in the study at each centre were collected

quarterly from each of the 22 participating centres (please

refer to supplementary Table 1 for more information).

Statistical Methods

Baseline, treatment data and the secondary endpoint of

safety were presented using summaries and descriptive

statistics. For continuous data median, minimum and

maximum were shown. To analyse categorical data, counts

and percentages were used.

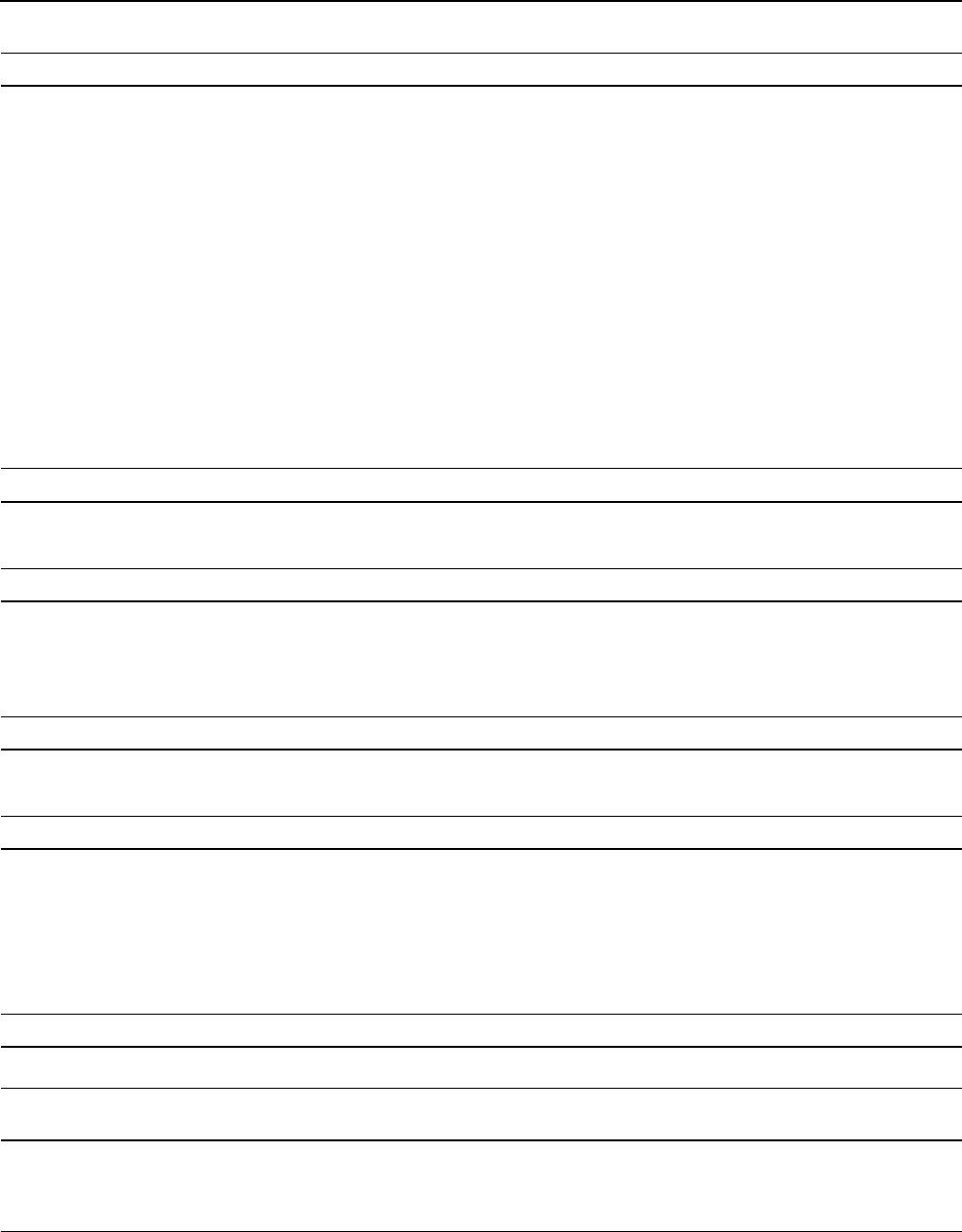

Table 1 Treatment intent (Primary outcome measurement)

Primary endpoint HCC

n = 114 (%)

ICC

n = 33 (%)

mCRC

n = 38 (%)

(A) First-line TARE treatment with or without concomitant systemic therapy 43 (37.7) 18 (54.5) –

(B) Second or subsequent line TARE treatment with or without concomitant systemic therapy after

previous first-line systemic therapy, including salvage therapy when no other systemic therapies

used alone are likely to be efficacious

7 (6.1) 8 (24.2) 20 (52.6)

(C) TARE treatment with or without concomitant systemic therapy after previous interventional

liver-directed procedures or liver surgery

50 (43.8) 1 (3.0) 2 (5.2)

(D) Addition of TARE to systemic therapy (any line) or to any other treatment (e.g. ablation)

intended as part of a multimodal curative therapy with any of the following objectives:

resectability and/or ablative therapy and/or transplantation

6 (5.3) 3 (9.1) 2 (5.2)

(E) Treatment with TARE in patients intolerant of chemotherapy or patients considered not

suitable for systemic therapy

2 (1.8) 1 (3.0) –

(F) Other 6 (5.3) 2 (6.1) 14 (36.8)

R. Loffroy et al.: Short-term Safety and Quality of Life Outcomes...

123

Table 2 Patient demographics and treatments before and after TARE

Patient demographics n (%)

Male 140 (70)

Age (median) (19, 92) 66

Disease characteristics

Primary liver cancer 151 (75.5)

Secondary/metastatic liver cancer 49 (24.5)

Primary tumours

HCC 114 (75.5)

ICC 33 (21.8)

Other 4 (2.7)

Metastatic liver cancer

CRC 38 (77.5)

NET 5 (10.2)

Gastric cancer 1 (2)

Lung cancer 1 (2)

Other (Prostate cancer, missing) 4 (8.2)

Prior hepatic procedures HCC n = 114 (%) ICC n = 33 (%) mCRC n = 38 (%)

Yes (subjects with at least one prior hepatic procedure) 61 (53.5) 2 (6.1) 18 (47.4)

No 53 (46.5) 31 (93.9) 20 (52.6)

Surgery HCC n = 16 (14.0) ICC n = 1 (3.0) mCRC n = 9 (23.7)

Liver surgery 13 (11.4) 1 (3.0) 9 (23.7)

Open 9 (7.9) 1 (3.0) 4 (10.5)

Laparoscopy 4 (3.5) – 2 (5.3)

Liver transplant 3 (2.6) – –

Ablation HCC n = 17 (14.9) ICC n = 0 (0) mCRC n = 4 (10.5)

Radiofrequency Ablation 9 (7.9) – 2 (5.3)

Microwave Ablation 10 (8.8) – 1 (2.6)

Intra-arterial treatments HCC n = 51 (44.7) ICC n = 1 (3.0) mCRC n = 4 (10.5)

Chemoembolization (TACE) 47 (41.2) – 2 (5.3)

Conventional TACE 45 (39.5) – 1 (2.6)

Drug-eluting TACE 2 (1.8) – 1 (2.6)

Hepatic-arterialchemotherapy – – 2 (5.3)

Bland embolization 1 (0.9) – –

Vascular other 2 (1.8) 1 (3.0) –

Radiation therapy (EBRT, Other) HCC n = 1 (0.9) ICC n = 0 (0) mCRC n = 0 (0)

Other (cyberknife) 1 (0.9) – –

Prior systemic chemotherapy HCC n = 16 (14) ICC n = 13 (40) mCRC n = 34 (90)

Hepatic Procedures after TARE HCC n = 114 (%) ICC n = 33 (%) mCRC n = 38 (%)

Yes (Subjects with at least one hepatic procedure after TARE) 24 (21.0) 3 (9.1) 2 (5.3)

No 82 (71.9) 28 (84.8) 31 (81.6)

Unknown/data not available 8 (7.1) 2 (6.1) 5 (13.1)

R. Loffroy et al.: Short-term Safety and Quality of Life Outcomes...

123

HRQOL data were plotted using RStudio under R 3.6.1.

For both questionnaires, changes of more than 10 points

were considered clinically relevant [15].

Results

Data Collection and Distribution of Patients

This interim report includes 200 patients, enrolled between

August 2017 and October 2019. Treatment data were

available for 98.5% and follow-up data for 93% of the

patients, respectively. 11 centres actively contributed

patient data, whereas another 11 centres performed no or

very few cases and did not provide patient data. Patient

numbers differed significantly between centres. In this

interim analysis, a vast majority of 81.5% (n = 163) were

treated at three sites; moreover, 54.5% (n = 109) of the

overall patient population was contributed by one site.

Median number of patients enrolled per site was 8.

With case logs collected quarterly from all 22 sites

involved in the study, it was determined that the achieved

coverage of all patients treated at participating sites was

84%. When disregarding one centre, the patient coverage

achieved was 91% (please refer to supplementary Table 1

for more information).

Patient Characteristics

Median age was 66 years (range 19–92), 140 (70%)

patients were male. Of all 200 patients, HCC represented

the majority (114, 57%) of cases, followed by mCRC (38,

19%) and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC; 33,

16.5%). Smaller cohorts were neuroendocrine tumour

(NET; 5, 2.5%), and other malignancies (10, 5%, see

Table 2).

More than half of the HCC patients (53.5%) underwent

liver-directed therapies before entering the study, mainly

conventional transarterial chemoembolization (TACE;

39.5%) and 14% prior systemic chemotherapy.

93.9% of ICC patients received no surgery or ablation

prior to TARE, but 40% received prior systemic

chemotherapy. While the majority (84.8%) of these

patients received no additional liver-directed treatment

after TARE, 66.7% received systemic chemotherapy

(Table 2).

In the mCRC cohort, 23.7% of patients received liver

surgery before TARE and 10.5% received tumour ablation.

Only 10% chemotherapy-naı

¨

ve patients were encountered

in the mCRC cohort, and 65.7% of patients received sys-

temic chemotherapy treatment after TARE.

Table 2 continued

Surgery HCC n = 4 (3.5) ICC n = 3 (9.1) mCRC n = 1 (2.7)

Liver surgery 1 (0.9) 3 (9.1) 1 (2.7)

Open 1 (0.9) 1 (3.0) 1 (2.7)

Laparoscopy – 2 (6.1) –

Liver transplant 3 (2.7) – –

Ablation HCC n = 4 (3.5) ICC n = 0 (0) mCRC n = 0 (0)

Radiofrequency ablation 1 (0.9) – –

Microwave ablation 2 (1.8) – –

Irreversible electroporation 1 (0.9) – –

Intra-arterial treatments HCC n = 22 (%) CC n = 0 (0) mCRC n = 1 (2.7)

Chemoembolization (TACE) 20 (17.5) – 1 (2.7)

Conventional TACE 16 (14.0) – –

Drug-eluting TACE 4 (3.5) – –

Hepatic-arterial chemotherapy 1 (0.9) – –

Bland embolization 1 (0.9) – –

Radiation therapy (TARE and EBRT) HCC n = 2 (1.8) I CC n = 0 (0) mCRC n = 0 (0)

Systemic chemotherapy after TARE HCCn = 28 (24.5) ICC n = 22 (66.7) mCRC n = 25 (65.7)

EBRT External beam radiation therapy

R. Loffroy et al.: Short-term Safety and Quality of Life Outcomes...

123

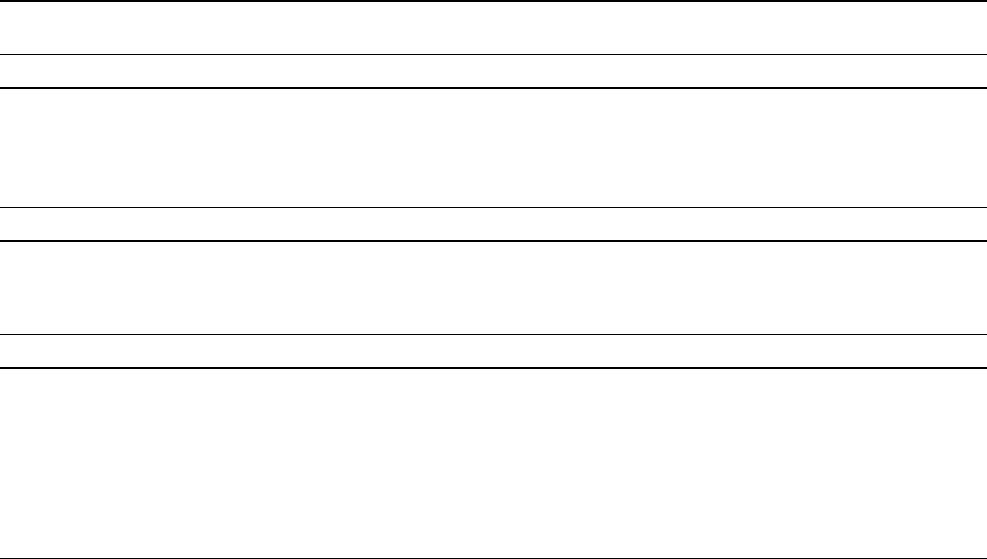

Table 3 Tumour location and

Tumour and Liver volumes

Liver tumour location HCC n = 114 (%) ICC n = 33 (%) mCRC n = 38 (%)

Left 22 (19.3) 6 (18.2) 3 (7.8)

Right 58 (50.9) 14 (42.4) 7 (18.4)

Bilobar 33 (28.9) 12 (36.4) 26 (68.4)

Unknown/data not available 1 (0.9) 1 (3.0) 2 (5.4)

Number of liver tumours

1 46 (40.3) 20 (60.6) 3 (7.9)

2 16 (14.0) 2 (6.1) 3 (7.9)

3 16 (14.0) 2 (6.1) 4 (10.5)

4 8 (7.0) – 2 (5.3)

5 4 (3.5) – 3 (7.9)

[ 5 7 (6.1) 3 (9.1) 8 (21.0)

Uncountable 15 (13.1) 5 (15.2) 11 (28.9)

Unknown/data not available 2 (1.8) 1 (2.9) 2 (5.3)

Liver and tumour volumes (mL) n = 195 Median (IQR)

Left lobe volume (mL) n = 55 638 (460.5)

Left tumour volume (mL) n = 35 60 (122.3)

Right lobe volume (mL) n = 54 1104.5 (623.4)

Right tumour volume (mL) n = 42 136 (341.5)

Total liver volume (mL) n = 129 1765 (910)

Total tumour volume (mL) n = 128 129.5 (363)

Tumour volume categories (mL) n = 197 (%)

1–50 41 (20.8)

51–100 37 (18.8)

101–200 30 (15.2)

201–500 43 (21.8)

501–1000 20 (10.2)

1001–2500 13 (6.6)

Unknown/data not available 13 (6.6)

Liver cirrhosis

Yes 81 (71.0) 4 (12.1) 1 (2.7)

Alcohol 20 (24.7) 3 (75) 1 (100)

Hepatitis B 2 (2.5) – –

Hepatitis C 19 (23.5) 1 (25) –

NAFLD 18 (22.2) – –

Alcohol ? Hepatitis C 6 (7.4) – –

Alcohol ? NAFLD 9 (11.1) – –

Other and unknown 7 (8.6) – –

No 33 (28.9) 28 (84.8) 35 (92.1)

Portal vein thrombosis (PVT) HCC n = 114 (%) ICC n = 33 (%) mCRC n = 38 (%)

Patent 79 (69.3) 28 (84.8) 33 (86.8)

Segmental 26 (22.8) 2 (6.1) 2 (5.3)

Lobar 5 (4.4) – –

Main 2 (1.8) 2 (6.1) –

Unknown/data not available 2 (1.8) 1 (3.0) 3 (7.9)

NAFLD non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

R. Loffroy et al.: Short-term Safety and Quality of Life Outcomes...

123

Table 4 Treatment procedure and administration

TARE treatment target Centre HCC n = 114 (%) ICC n = 33 (%) mCRC n = 38 (%)

Whole liver (single catheter) 1 1 (0.9) – –

2 – – 4 (10.5)

3 – – 1 (2.6)

6 – – 2 (5.3)

Whole liver (split administration/single session) 2 1 (0.9) 3 (9.1) 5 (13.2)

3 – 1 (3.0) –

6 – – 4 (10.5)

8 – – 1 (2.6)

Whole liver (sequential lobar/two sessions) 3 4 (3.5) – –

5 2 (1.8) – 1 (2.6)

Right lobe 1 45 (39.5) 15 (45.5) 5 (13.2)

2 4 (3.5) – 3 (7.9)

3 6 (5.3) – –

4 3 (2.6) 2 (6.1) –

5 2 (1.8) 1 (3.0) 2 (5.3)

6 2 (5.3)

7 2 (1.8) – 1 (2.6)

8 1 (0.9) – –

10 1 (0.9) – –

Left lobe 1 18 (15.8) 5 (15.2) 1 (2.6)

2 4 (3.5) – 1 (2.6)

3 5 (4.4) – 1 (2.6)

4 2 (1.8) 1 (3.0) –

5 – – 1 (2.6)

9 1 (0.9) – –

Segmental 1 4 (3.5) 3 (9.1) –

2 4 (3.5) 1 (3.0) 1 (2.6)

3 1 (0.9) – –

7 1 (0.9) – –

Unknown/data not available 1 1 (0.9) – –

7 – 1 (3.0) 2 (5.3)

11 1 (0.9) – –

Methodology for determining the dose

BSA 12 (10.5) 5 (15.2) 19 (50.0)

Modified BSA 19 (16.7) 1 (3.0) 5 (13.2)

Partition model 78 (68.4) 26 (78.8) 8 (21.0)

Other 2 (1.8) – –

Unknown/ data not available 3 (2.6) 1 (3.0) 6 (15.8)

Prescribed/delivered activity n = 231 (%)

Median prescribed activity whole (n = 126) 1 GBq

Unknown/data not available 3

Median prescribed activity right, GBq (n = 56) 1.2 GBq

Unknown/data not available 18

Median prescribed activity left, GBq (n = 40) 0.7 GBq

Unknown/data not available 34

R. Loffroy et al.: Short-term Safety and Quality of Life Outcomes...

123

Treatment Intent

Regarding the primary outcome of CIRT-FR, 37.7% of

HCC (n = 43/114) and 54.5% of ICC (n = 18/33) patients

underwent TARE with SIR-Spheres as a first-line treatment

(Table 1). 43.8% (n = 50/114) HCC, 3% (n = 1/33) ICC

and 5.2% (n = 2/38) mCRC patients received the treatment

after previous liver-directed interventional radiological

procedures or liver surgery in the absence of prior

chemotherapy and post-hepatic procedures. A total of

52.6% (n = 20/38) of mCRC patients, 24.2% (n = 8/33) of

ICC and 6.1% (n = 7/114) of HCC patients received TARE

treatment after previous first-line systemic therapy.

Tumour and Treatment-Related Characteristics

Please refer to Tables 3 and 4 for detailed information.

Safety

Peri-procedural adverse events were reported during

treatment for 8 (4%) patients, and 189 (94.5%) patients did

not present with peri-procedural adverse events (see

Table 5).

Within 30 days following treatment, 24 (12%) of

patients experienced at least one AE and a total of 42 AE,

with 82% of graded AEs reported to be mild to moderate

(i.e. grade 1 or 2). Six grade 3 AEs in three patients (GI

ulceration, radioembolization induced liver disease

(REILD), jaundice, oedema and dyspnoea) were reported.

No AE grade 4 or 5 was reported during the first 30 days.

Overall, 122 (61%) patients experienced at least one AE

more than 30 days following treatment and a total of 382

AE, with 83% of graded AEs being reported as moderate.

36 (9.4%) AEs in 28 (14%) patients were grade 3 or 4, and

no AEs grade 5 was reported. 168 (44%) AEs were not

graded. AEs of special relevance or interest for TARE are

listed in Table 5 together with commonly reported AEs.

The remaining reported AEs are categorised in Table 5,

section ‘’Less common AEs’’. No radiation induced

pneumonitis, cholecystitis or pancreatitis were reported in

the cohort.

Quality of Life

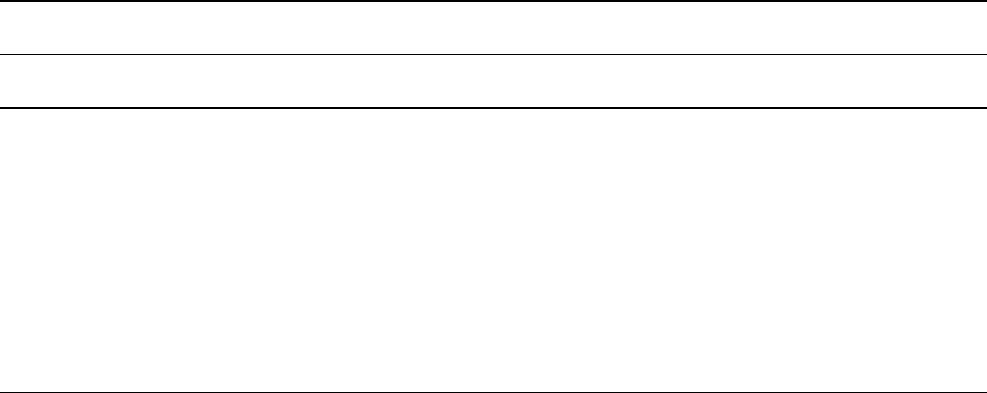

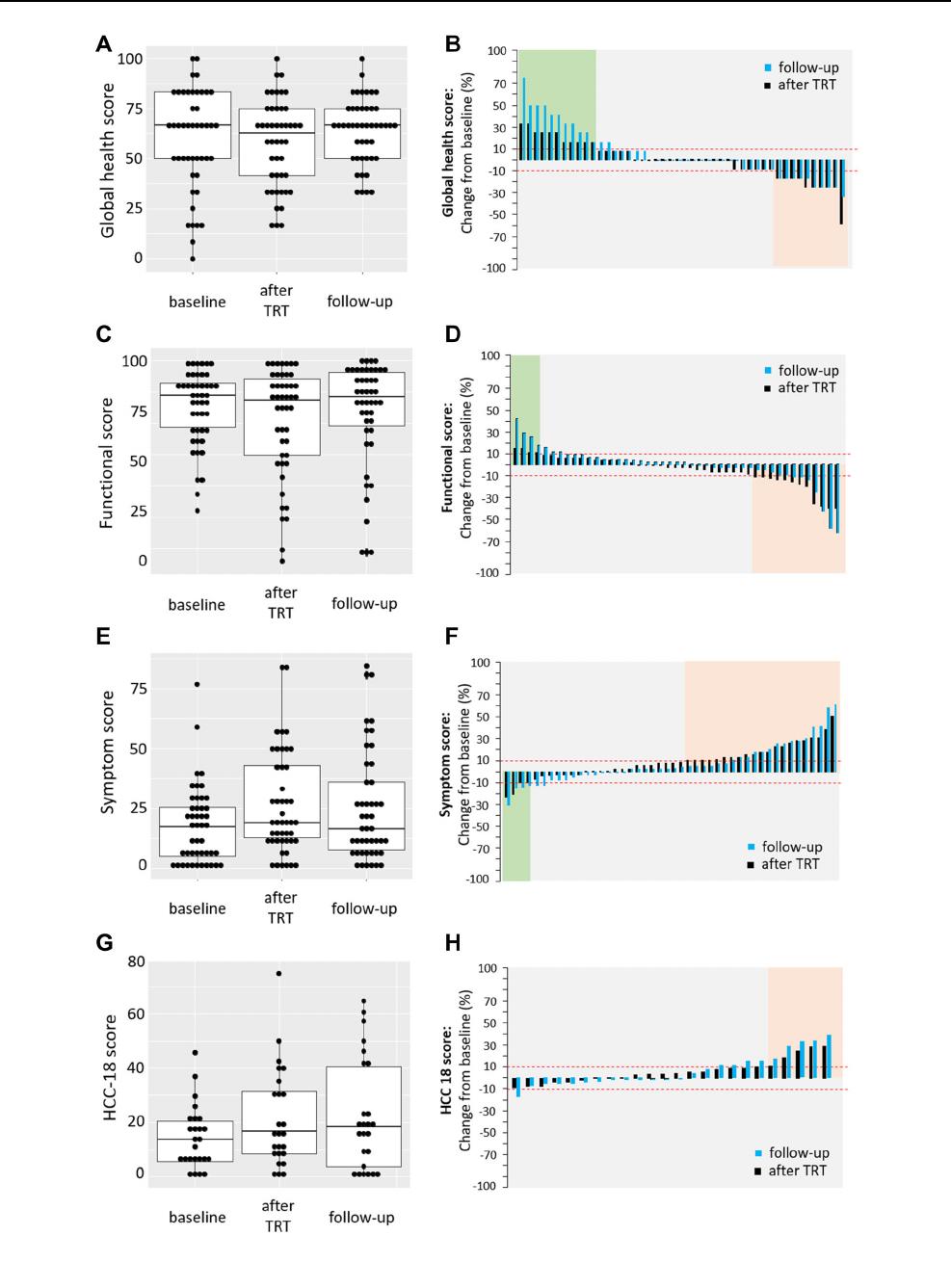

Health-related quality of life was assessed using the

EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire at baseline (range 99 –

0 days before treatment), within one week after treatment

and on the first follow-up at an average of 13 weeks (range

5–19) following treatment for the 23% of patients that had

questionnaires available for all three timepoints. Fig-

ure 1A, C and E shows that the median HRQOL at baseline

compared to after treatment and the first follow-up remains

stable for the global health score (66.7% vs. 62.5% and

66.7%), for the functional score (86.2% vs. 84.4% and

83.3%) and for symptom score (17.9% vs. 20.5% and

15.4%).

At a patient level, when comparing baseline to after

treatment, improvement indicated by an increase in more

than 10 points was seen in 23.9% for global health and

8.6% for functional and a decline by more than 10 points in

21.7 and 26%, respectively (Fig. 1B, D, black colour). A

decline in symptoms and thus improvement of HRQOL

was seen in 8.6% vs 45.6% showing increased symptoms

(Fig. 1F, black colour). The number of patients with

increased or decreased HRQOL did not change by much

when comparing the first follow-up to baseline (Fig. 1B, D,

F light colour). Quality of life status was distributed evenly

across indications (data not shown).

With regards to the HCC18 Module, information was

provided for 25 (22%) HCC patients at baseline at an

average of 13 days before treatment (range 0 to 43),

immediately after treatment and on the first follow-up at an

average of 13 weeks (range 5.4 to 18.4) following

Table 4 continued

Prescribed/delivered activity n = 231 (%)

Delivered activity within 90% of the prescribed activity n = 197 (%)

Yes 188 (95.4)

No 3 (1.5)

Unknown/data not available 6 (3.0)

Number of administrations delivered n = 197 (%)

1 59 (29.9)

2 24 (12.2)

3 3 (1.5)

Unknown/data not available 111 (56.3)

BSA, body surface area; GBq, gigabecquerel

R. Loffroy et al.: Short-term Safety and Quality of Life Outcomes...

123

Table 5 Peri-interventional adverse events (AE) and AEs summary

Peri-interventional AEs \ 30 days [ 30 days

Overall AE

n = 9 (%)

AEs Grade 3 or 4

n = 6 (%)

Overall AE

n = 42 (%)

AEs Grade 3

n = 6 (%)

Overall AE

n = 382 (%)

AEs Grade 3 or 4

n = 36 (%)

Abdominal pain 4 (44.4) 4 (66.7) 2 (4.8) – 50 (13.1) 4 (11.1)

Fatigue – – 11 (26.2) – 91 (23.8) 8 (22.2)

Fever – – – – 9 (2.4) –

Nausea – – 4 (9.5) – 16 (4.2) –

Vomiting 1 (11.1) 1 (16.7) 4 (9.5) – 6 (1.6) 1 (2.8)

RE Induced Gastritis – – 1 (2.4) – – –

Gastritis – – – – 2 (0.5) –

RE Induced GI Ulceration – – 1 (2.4) – – –

GI Ulceration – – 1 (2.4) 1(16.7) 3 (0.8) 2 (5.6)

REILD – – 1 (2.4) 1 (16.7) – –

Radiation Pneumonitis – – – – – –

Radiation Cholecystitis – – – – – –

Radiation Pancreatitis – – – – – –

Ascites – – – – 16 (4.2) –

Dyspnoea – – 3 (7.1) 2 (33.3) 7 (1.8) 1 (2.8)

Hepatic enteropathy – – – – 8 (2.1) 4 (11.1)

Neuropathy – – – – 9 (2.4) 1 (2.8)

Hand–foot syndrome – – – – 13 (3.4) 1 (2.8)

Anorexia – – 1 (2.1) – 15 (4.0) 4 (11.1)

Constipation – – – – 9 (2.4) –

Diarrhoea – – – – 34 (8.9) 1 (2.8)

Anaemia – – – – 15 (4.0) 1 (2.8)

Jaundice – – 2 (4.8) 1 (16.7) 4 (1.0) –

Oedema – – 3 (7.2) 1 (16.7) 3 (0.8) –

Less common AEs 4 (44.4) 1 (16.7) 8 (19.1) – 72 (18.8) 8 (22.2)

Bleeding 4 (44.4) 1 (16.7) 2 (4.8) – 5 (1.3) –

Liver and portal system – – 12 (3.2) 2 (5.6)

Cardio-pulmonary – – – – 5 (1.3) –

Neurological, pain, and other

sensitive disorders

– – – – 15 (3.9) –

General – – 4 (9.5) – 9 (2.4) 1 (2.8)

Digestive – – 1 (2.4) – 9 (2.4) –

Analytical – – – – 4 (1.0) 1 (2.8)

Cutaneous complications – – 1 (2.4) – 7 (1.8) 1 (2.8)

Musculoskeletal disorders – – – – 3 (0.8) –

Pancreatitis – – – – 2 (0.5) 2 (5.6)

Renal and fluid balance – – – – 1 (0.3) 1 (2.8)

Peri–interventional \ 30 days [ 30 days

Overall Grade 3 or 4 Overall Grade 3 Overall Grade 3 or 4

Subjects with at least one AE

n = 200 (%)

8 (4) 4 (2) 24 (12) 3 (1.5) 122 (61) 28 (14)

REILD,radioembolization-induced liver disease; GI gastrointestinal

189 (94.5%) patients had no severe peri-interventional AEs. For 3 (1.5%) patients, no information was collected. Subjects with at least one peri-

interventional AEs were 8 (4%), of which 4(2%) had grade 3. There were 4 (2%) other peri-interventional AEs reported in 4 patients (three vascular

minor and one blood transfusion) no grading for these four AEs was provided. A total of 42 AEs were observed in 24 patients within 30 days

following treatment of which 6 were grade 3 (GI Ulceration, REILD, jaundice, oedema and dyspnoea). No AE grade 4 or 5 were observed during

the first 30 days after treatment

R. Loffroy et al.: Short-term Safety and Quality of Life Outcomes...

123

R. Loffroy et al.: Short-term Safety and Quality of Life Outcomes...

123