457

THE

FORMATION

OF

THIN

FILMS

AND

FIBERS OF

TiC

FROM

A

POLYMERIC

TITANATE

PRECURSOR

S-J.

Ting,

C-J.

Chu,

E.

Limatta,

J.

D.

Mackenzie*

and

T.

Getman,

M.

F.

Hawthorne-

Department

of

Materials

Science

and

Engineering

and

**

Department

of

Chemistry

and

Biochemistry,

University

of

California

at

Los

Angeles,

Los

Angeles,

CA

90024

ABSTRACT

The

synthesis

and

characterization

of

several

polymeric

titanates

and

their conversion

to

carbon

deficient

TIC

is

described.

The

physical

properties

of

one

of

these

titanates

allows

it

to

be

drawn

into

fibers

and

applied to

substrates

as

thin

films.

Pyrolysis

of

these

fibers

and

films

to

carbon

deficient

TiC

is

described.

INTRODUCTION

The

preparation

of

metallic

carbides

via

metal-organic

precursors

is

now

well

known

[1-7].

However,

while

it

is

relatively

easy

to

prepare

ceramic carbide

powders it

is

extremely

difficult

to

fabricate

fibers

directly from

the

precursors.

Titanium

alkoxides

are

known

to

undergo

trans-

esterification

[81

with

carboxylic

acid

esters.

This

approach

has

been

employed

in

the preparation

of

titanium

alkoxides

which

could

not

be

prepared

via

other

routes

[8].

The

formation

of

polymeric

titanium

alkoxides

via

the transesterification

of

Ti(O-iC3H7)4

with

bifunctional

acetates

and

their

subsequent

pyrolysis

to

TiCx

(x<l)

is

described

below.

One

prerequesite

of

such

polymers

is

that

they

contain

excess

carbon

which,

during

the

pyrolysis

process,

will

"burn-off"

the

oxygen

in

the

system

as

carbon

monoxide.

This

work

represents

part

of

our

ongoing

research

which

pertains

to the

preparation

of

thin

films

and

fibers

of

amorphous

carbides, amorphous

oxycarbides and

crystalline

carbides

from

metal-organic

precursors.

EXPERIMENTAL

Syntheses

of

Polymeric

Titanium

Alkoxides:

The

typical

procedure

for

conducting

reaction

H

(see

Table

1)

involved

the

interaction

of

2.22

g

(7.99

mmol)

of

Ti(O-i-C

3

H7)4

with

1.05

equivalents

(1.87

g,

8.40

mmol)

of

a,cz'-dlacetate-o-xylene

in

toluene

(200-250

mL).

The

Ti(O-i-C

3

H7)4

was

weighed

in

the

dry

box

and

quantitatively

transfered,

using

toluene

as

solvent,

to

a

3-neck

reaction flask

which

was

stoppered

via

two

stoppers

and

one stopcock.

The

c,c,-diacetate-o-xylene,

previously

dissolved

in

dry

deoxygenated

toluene,

was

then transfered

onto

the

Ti(O-i-C

3

H

7

)

4

via

a

Cannula.

An

additional

200

mL

of

dry

deoxygenated

toluene

was

added

to

this

solution. Under

a

flush

of

N2

gas

the stoppers

were

replaced

by

a

Dean-Starke

trap

and

condenser

and

by

a reservoir

bulb

which

was

filled

with

(250

mL)

of

dry

deoxygenated

toluene.

The

reaction

mixture

was

brought to

reflux

and

the

distillate

which

collected

in

the

Dean-Starke

trap was

periodically

drained

off

and

its

IR

spectrum

observed.

This

was

continued

until

the

IR

absorption

at

_-1740

cm-

1

attributable to

the

carbonyl

group

of

isopropyl

acetate

was

no

longer

observed

in

the

distillate.

Periodically

some

toluene

from

the

reservoir

was

added

to

the

reaction

to

prevent

it

from distilling

to

dryness.

The

resulting

solution

was

filtered

and

the

toluene

was

removed

under reduced

pressure

to

yield

1.02

g (42%

based

upon

Ti(O-i-C

3

H7)4)

of

a

tacky polymer.

1

H

FT-NMR

data:

7.55-6.79

ppm

multiple

resonances

with

a

maximum at

7.11

ppm

(D

+ E),

5.72-4.20

ppm

multiple

resonances

with

maxima

at

5.24

ppm

and

4.44

ppm

(C

+

B),

2.25

ppm

(F),

1.61-0.39

ppm

with

a

maximum

at

1.14

ppm

(A).

Integrated

areas

20.9

:

25.1

: 1

:

61.5,

respectively.

Theoretical

areas

if x

=

15 (Figure

1);

20

:

30

: 1 :

62.

Using

15

as a

good

approximation

of

x,

the

MWave

of

product

H

was

4636.

13

C

FT-NMR

data:

142-139

ppm

mulitple

resonances

(G),

131-125 ppm

multiple

resonances

(D +

E),

79-70 ppm

multiple

resonances

(C

+ B),

27-25 ppm

multiple

resonances

(A),

21.3 ppm

(F), no

resonance

assignable

to

carbon

(H) was

observed

in

the

area

of

170

ppm.

The

assignments

refer

to

the

corresponding

carbon

atoms

labeled

in

Figure

1 or

in

the

case

of

the

1

H

FT-NMR

the hydrogens

bonded

to

them.

IR

data(cm-1):

C-H

2968

(m),

2865

(m),

unassigned

1457(m), 1365

(m),

1328

(m),

1214

(m),

1060-950

(s,

br)

with

Reactions

A -

G

were

performed

in

a

similar

manner.

The soluble

products

from

reactions

A -

G

were

characterized

spectroscopically

by

IR,

1

H

FT-NMR

and

13

C FT-NMR.

Insoluble

products

were

characterized

spectroscopically

by

IR

and solid-state

13

C

FT-CPMAS-NMR.

Mat.

Res.

Soc.

Symp. Proc.

Vol.

180.

@1990

Materials

Research Society

458

Thin

Film

and

Fiber

Formation:

All

the

low

temperature

(<600

0

C)

sample-heating

was

carried

out

in

the

dry box

under

nitrogen

in

a

home-built

furnace.

All

the

high

temperature

(>600

0

C)

sample-heating

was

carried

out

under

argon

in

a

high

temperature

furnace

(Thermal

Technology

Inc.

Astro

1

OOOA).

The

structures

of

the

thermalized

samples

at different

temperatures

were

investigated

using

solid-state

13

C-CPMAS-NMR

and/or

IR

spectroscopy.

Samples

pyrolyzed

at

temperatures

higher

than

1000

0

C

were

studied

using

XRD.

Hand-drawn fibers

were

obtained

from

product

H and

cured

at

80

0

C

overnight

in

the

dry box

under

a

nitrogen

atmosphere.

The

cured

fibers

were

then

pyrolyzed

very

slowly

to

500

0

C

under

nitrogen.

The resulting

titanium

oxycarbide fibers

were then

heated

to 1500

0

C

under

argon

for

4

hours.

Thin

films

were

prepared

by

dipping

a

fused

quartz

or

silicon

substrate

into

a

hexane

solution

of

product

H.

The

samples

were

then

fired

in

an

inert

atmosphere

from

500-1000

0

C

for

1

hour.

SEM,

ellipsometer

and

Dektak

were

used

to

study

the

thickness and

morphology

of

the

films.

DC

conductivity

was

measured

by

the

four

probe

method.

UV-vis

and IR

spectroscopy were

also

used

to

characterize

the

optical

properties

of

the

films.

RESULTS

AND

DISCUSSION

Synthesis

and

Characterization

of

Polymeric Titanium

Alkoxides:

The

reaction

of

Ti(O-i-C

3

H7)4

with

pentaerythritol

tetraacetate

(equation 1)

led

to

the

formation

of

a

polymeric

titanium alkoxide

(product

A).

0

-,,0OCH

2

,

,CH

2

-O--

0

Ti(O-.-C

3

HT)4

+

C(CH2OCCH

3

)

4

rTilO

CHc -

+

4 CH

3

CO--i-C

3

7

(1)

The

equilibrium

of

equation

1 was

forced

to

the

right

by

distilling

away

the

isopropyl

acetate

as

it

was

formed. However,

as

evidenced

by

IR and

solid-state

1

3

C-CPMAS-NMR,

the

reaction

could

not

be

driven

totally

to

completion.

Presumably,

this

was

due

to

the

non-ideality

of

the

polymer formed

and

its

lack

of

sufficient

flexibility

to allow

all

the

active

sites

to

react

with

one

another.

The

encouraging results

obtained

upon

pyrolysis

of

product

A

(see

bleow)

led

us

to

investigate

other

acetates

in

the

reaction

with

Ti(O-i-C

3

H7)

4

,

equation

2.

9

9 17

[-.-C

H~

"Ti(o-i-C

3

H

7

)

4

+ x

CH

3

CO-Unk-OCCH

3

-

I'-CH7)4.2x

2x

CH

3

CO-J-C

3

H

7

(2)

-L-T-{-Unk-)-O)-.•

The

results

of

these

studies are

presented

below

in

Table

I.

The

viscous

tacky

nature

of

product

H

allowed

it

to

be

drawn

into

fibers

and

applied

on

substrates

as

thin

films.

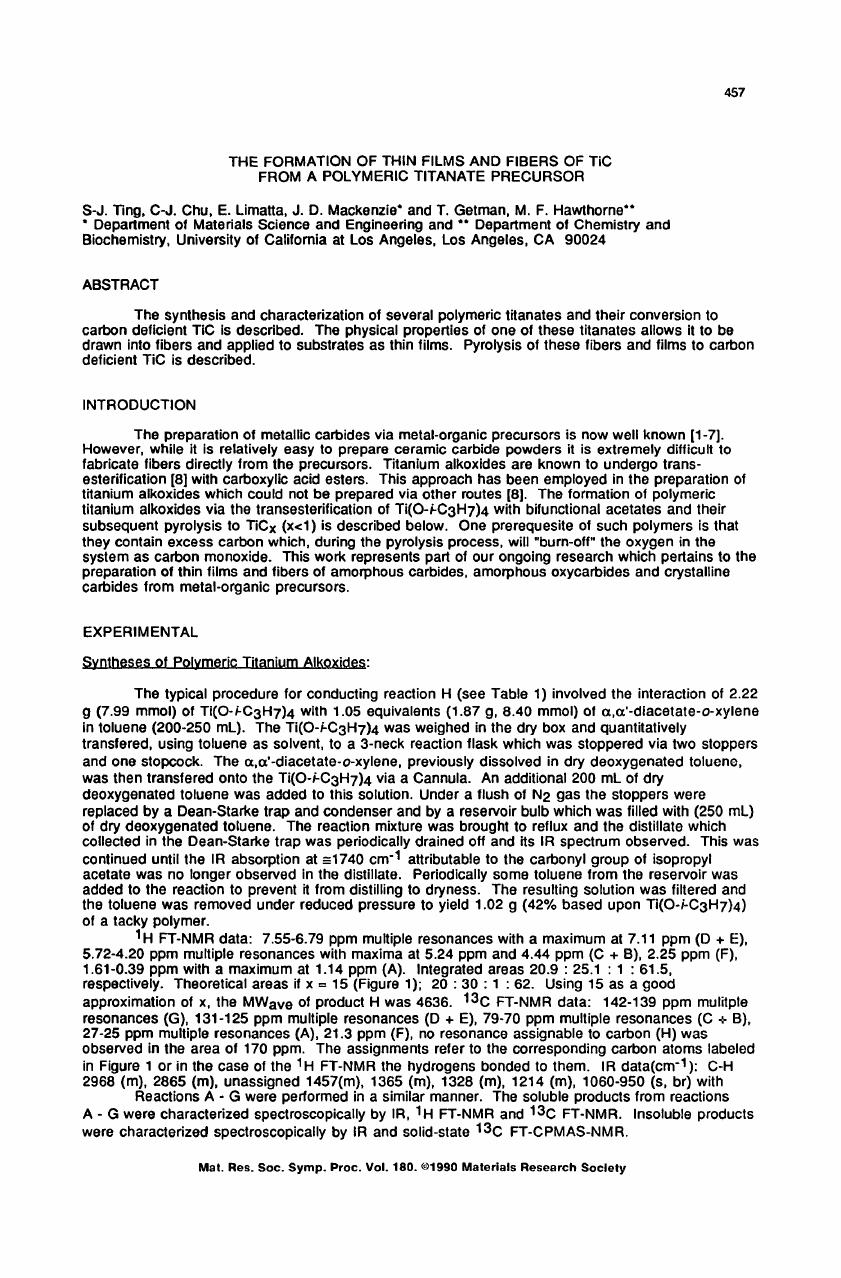

The

spectroscopic

data

for

product

H

is

given

in

the

experimental

section

and

a

representation

of

its

postulated

structure

is

shown

in

Figure

1.

end

group

B

A

end

group

B

A

(O-CH(CH

3

)

2

)

2

.O-H(CH

3

)

2

D•I

I

L..-

T`.-Q,

0

D 0-

-CCH

3

L

c

.j

Figure

1:

A representation

of

product

H.

Formation

of

Thin

Films

and

Fibers

of

Carbon

Difficient

TiC

from

Product

H:

The

gel

which

resulted

from

reaction

A was

pyrolyzed

at

1050

0

C

and

shown

to

produce

both

Ti203

and

TiCx

(x<l)

while

at

1500

0

C TiCx

(x<l)

was

formed

as

determined

by

XRD. This

encouraging

result

led

us

to

investigate

other

polymeric

titanium

alkoxides

for

use

as

precursors

to

thin

films

and

fibers

of

TiC.

TGA

analysis

of

product

H

revealed

a

60%

weight

loss

between

100

and

450

0

C

and

an

additional

2-3%

weight

loss

from

450-870

0

C.

The

weight

loss above

870

0

C

was

not

determined

due

459

to

the

limitations

of

the

TGA

apparatus.

The

solid-state

13

C-CPMAS-NMR

and

IR

spectra

of

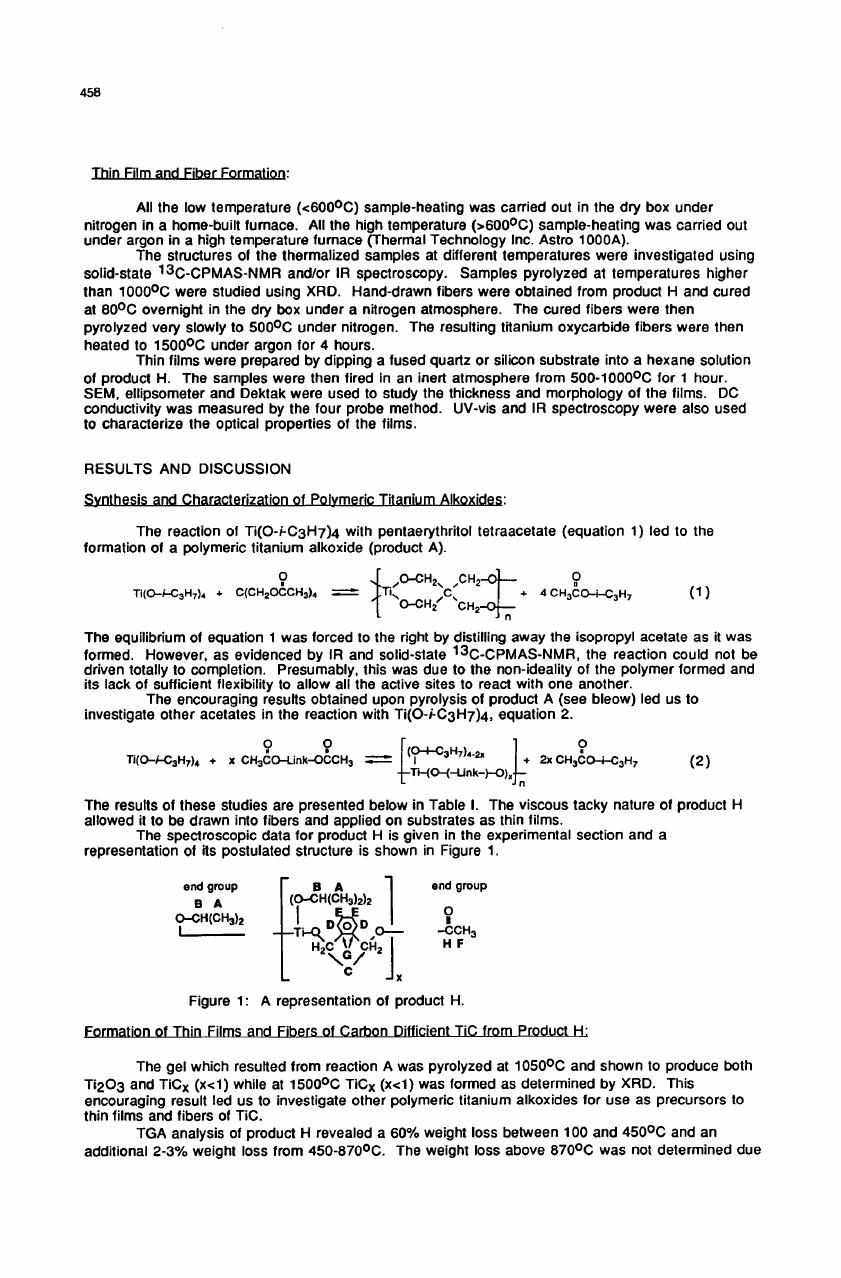

Table 1:

Summary

at

Reactions

of

Acetate

Eaters

with

Ti(O.-.-C3H,)

Bsa1ns

Thesetca

RAID

Stlotlchoetry

Acetato

A~sdXLQ=rkM)4

o cLmraug

0

A C(CHOCCH

3

)

4

9

9

CH

3

CO-(-CH7-)

3

-OCCH

3

9

9

C CHnCO-(-CH-.-OhCCHn

9

9

0 CH

3

CO-(-CH2-)

4

-OCCN

3

9

9

E

CH300-CHjr- CH

2

00CH

3

9

9

F CH

3

CO-CHfr"-

CH

2

OCCH3

CH

2

00CH

3

CH

2

0CCH

3

9

HCH

2

OCCI

3

,.,O-CH2,

,H -

:1

<

'C:C•

-• _CH

2

.

.CH-O-.On

Terrp(sl)re

Al WhichTI1C.(W~)

Insoluble

Insoluble

1.1

-[-Hn-o+cHC)4

-;.

u•I.b

"

0-t

CH2-)

4

-0f

2:1

,,l•o-(-c~z-),-o•

4

cTu.,O-"

• CH

2

O

2:1

{

0ocH.-@-CH.,o",

1:1

(04-C

[to-ic,,.i,,tu

l

1:12

C

I 500C

NA

16DO'C

toluene,

benzene.

No

TC

producd

and

cHaC'2

only

To

3

lnsoolble

1200"C

Insoluble 1200°C

Insoluble

soluble n

toluana,

ltervans

and C14Cl,

1200*C

1200"C

a

sample

pyrolyzed

at

180

0

C

exhibited

characteristic

C-O

peaks

around

77

ppm

and

1050

cm-

1

,

respectively.

The

conversion

process

of

product

H

to

TiCx

(x<l)

was studied

at

various

temperatures

(180,

260,

360,

500,

700

0

C)

using

solid-state

13

C-CPMAS-NMR

and

IR

spectroscopy.

The

NMR

and IR

spectra

revealed

that

the

C-O

bonds in

product

H

were

broken

by

260

0

C,

producing

titanium

oxide

and

unsaturated

hydrocarbon

fragments.

Chemical

analyses

of

several

samples

of

product

H

pyrolyzed

at

temperatures

from

180

to

1500

0

C

were

obtained and

are

listed

in

Table

II.

These

results

indicate

that

the

weight

loss

from

260

to

700

0

C is

primarily

due

to

the

elimination

of

hydrogen

and

some

carbon

and

oxygen.

However,

above

700

0

C

carboreduction

occurs,

resulting

in

the

production

of

a

titanium

oxycarbide.

The

IR spectrum

of

the

700

0

C

sample

indicates

the

reformation

of

C-O

bonds.

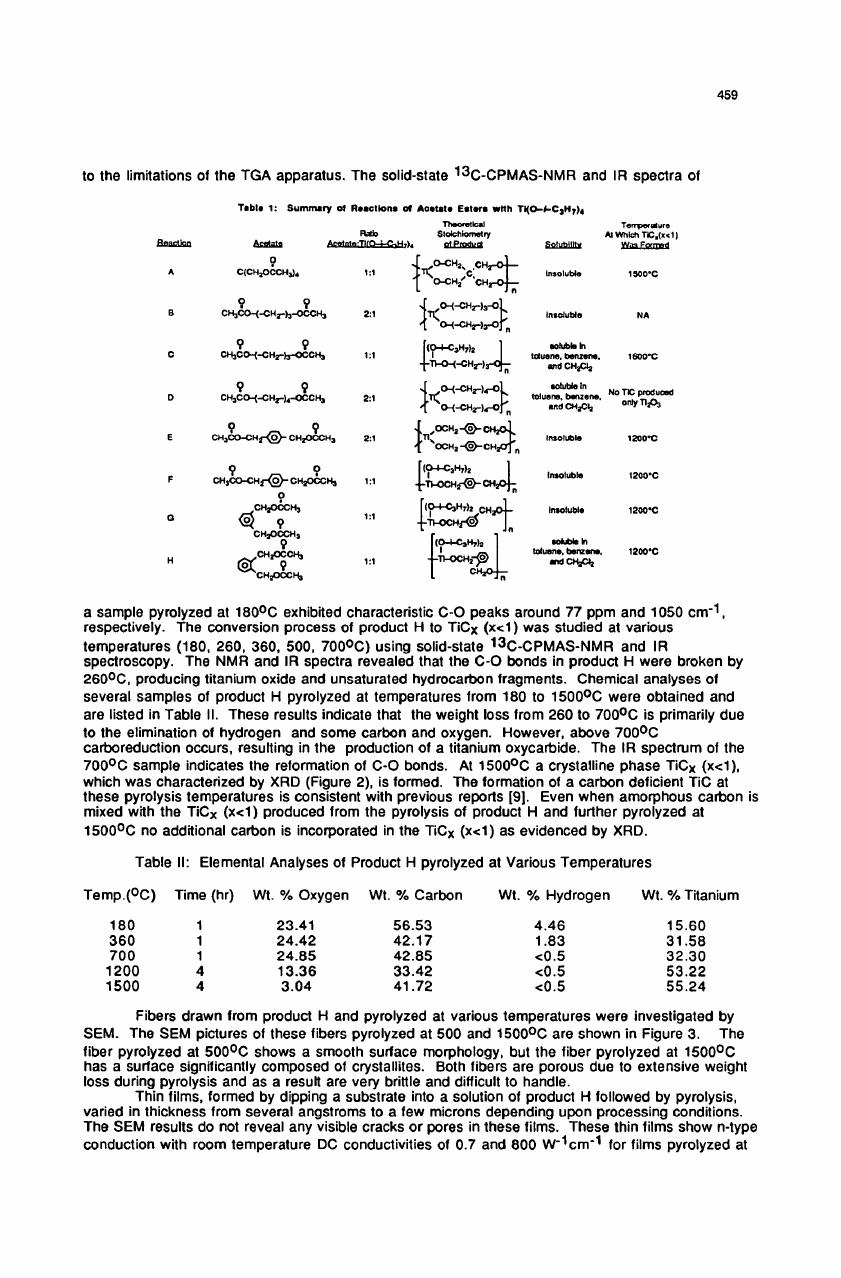

At

1500

0

C

a

crystalline

phase

TiCx

(x<l),

which

was

characterized

by XRD

(Figure

2), is

formed.

The

formation

of

a

carbon

deficient

TiC

at

these

pyrolysis

temperatures

is

consistent

with

previous

reports

[9].

Even

when

amorphous

carbon

is

mixed

with

the

TiCx

(x<l)

produced

from

the

pyrolysis

of

product

H

and

further

pyrolyzed

at

1500

0

C

no

additional

carbon

is

incorporated

in

the

TiCx

(x<l)

as

evidenced

by

XRD.

Table

Ih:

Elemental

Analyses

of

Product

H

pyrolyzed

at

Various

Temperatures

Temp.(OC)

Time

(hr)

Wt.

%

Oxygen

Wt.

%

Carbon

Wt.

%

Hydrogen

Wt.

%

Titanium

180

360

700

1200

1500

4

4

23.41

24.42

24.85

13.36

3.04

56.53

42.17

42.85

33.42

41.72

4.46

1.83

<0.5

<0.5

<0.5

15.60

31.58

32.30

53.22

55.24

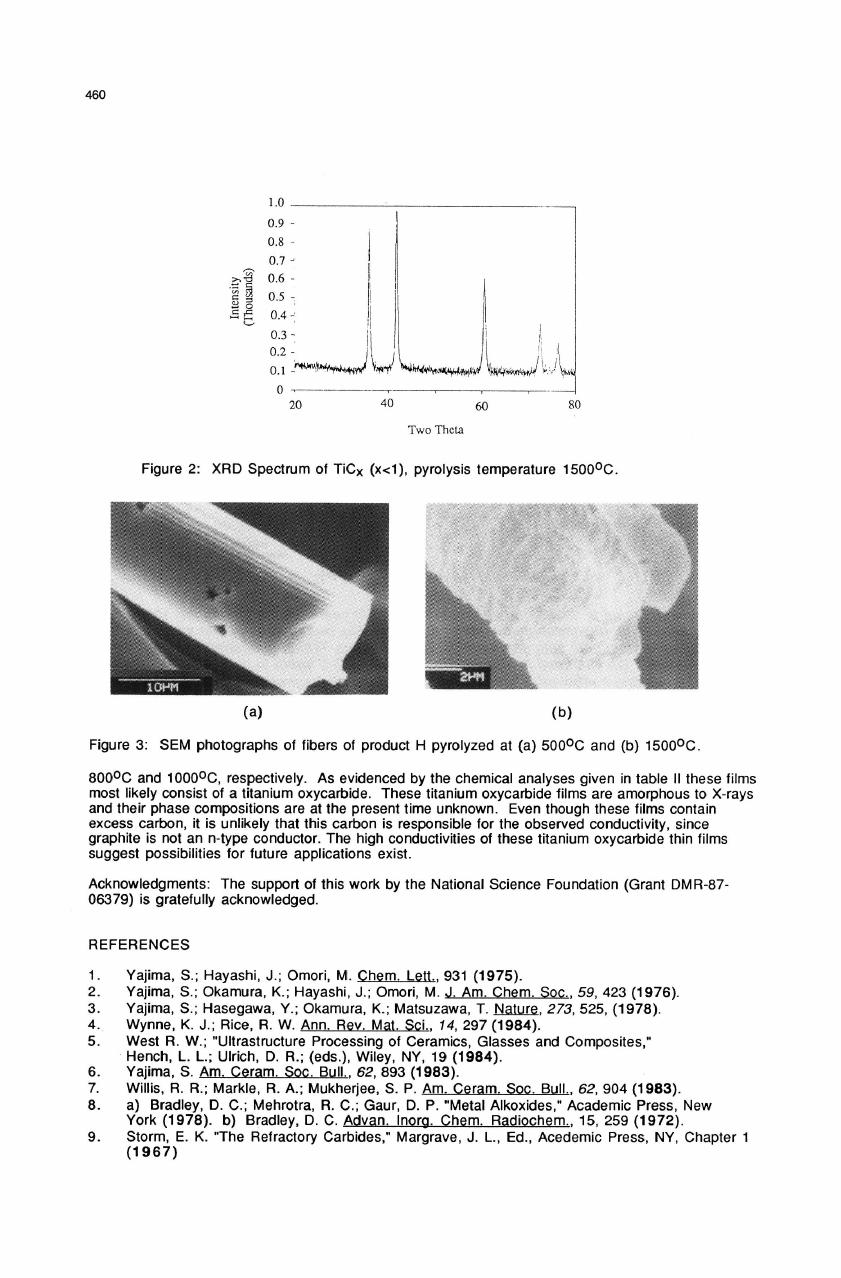

Fibers drawn

from

product

H

and

pyrolyzed

at various

temperatures

were

investigated

by

SEM.

The

SEM

pictures

of

these

fibers

pyrolyzed

at 500

and

1500

0

C

are

shown

in

Figure

3.

The

fiber

pyrolyzed

at

500

0

C

shows

a

smooth

surface

morphology,

but

the

fiber

pyrolyzed

at

1500

0

C

has

a

surface

significantly

composed

of

crystallites.

Both

fibers

are

porous

due

to

extensive

weight

loss

during

pyrolysis

and

as

a

result

are

very

brittle

and

difficult

to

handle.

Thin

films,

formed

by

dipping

a

substrate

into

a

solution

of

product

H

followed

by

pyrolysis,

varied

in

thickness

from

several angstroms

to

a

few

microns

depending

upon

processing

conditions.

The

SEM

results

do

not

reveal

any

visible

cracks

or pores

in

these

films.

These

thin

films

show

n-type

conduction

with

room

temperature

DC

conductivities

of

0.7

and

800

W'

1

cm"

1

for

films

pyrolyzed

at

460

1.0

0.9

0.8

0.7

0.6

0.5

-

0.4

-

0.3-

0.

1

0-.---1

_

20

40

l4

h

60

80

Two

Theta

Figure

2:

XRD

Spectrum

of TiCx

(x<l),

pyrolysis

temperature

1500

0

C.

(a)

(b)

Figure

3: SEM

photographs

of

fibers

of

product

H

pyrolyzed

at (a)

5000C

and

(b)

15000C.

800

0

C

and

1000

0

C,

respectively.

As

evidenced

by

the

chemical

analyses

given

in

table

II

these

films

most

likely

consist

of

a

titanium

oxycarbide.

These

titanium

oxycarbide

films

are

amorphous

to

X-rays

and

their

phase

compositions

are

at

the

present

time unknown.

Even

though

these

films

contain

excess

carbon,

it

is

unlikely

that

this

carbon

is

responsible

for

the

observed

conductivity,

since

graphite

is

not

an

n-type

conductor.

The

high

conductivities

of

these

titanium

oxycarbide

thin

films

suggest

possibilities

for

future

applications

exist.

Acknowledgments:

The

support

of

this

work

by

the

National

Science

Foundation (Grant

DMR-87-

06379)

is

gratefully

acknowledged.

REFERENCES

1.

Yajima,

S.;

Hayashi,

J.;

Omori,

M.

Chem.

Lett.,

931

(1975).

2.

Yajima,

S.;

Okamura,

K.;

Hayashi, J.;

Omori,

M.

J.

Am.

Chem.

Soc.,

59,

423

(1976).

3.

Yajima,

S.;

Hasegawa,

Y.;

Okamura,

K.;

Matsuzawa,

T.

Nature,

273,

525,

(1978).

4.

Wynne,

K.

J.;

Rice,

R.

W.

Ann.

Rev.

Mat.

Sdi., 14,

297

(1984).

5.

West

R.

W.;

"Ultrastructure

Processing

of

Ceramics,

Glasses

and

Composites,"

Hench,

L.

L.;

Ulrich,

D.

R.;

(eds.),

Wiley,

NY,

19

(1984).

6.

Yajima,

S.

Am.

Ceram.

Soc.

Bull.,

62,

893

(1983).

7.

Willis,

R.

R.;

Markle,

R.

A.;

Mukherjee,

S.

P.

Am.

Ceram. Soc.

Bull.,

62,

904

(1983).

8.

a) Bradley,

D.

C.;

Mehrotra,

R.

C.;

Gaur,

D.

P.

"Metal

Alkoxides,"

Academic

Press,

New

York

(1978).

b)

Bradley,

D.

C.

Advan.

Inorg.

Chem.

Radiochem.,

15,

259

(1972).

9.

Storm,

E. K.

"The

Refractory

Carbides,"

Margrave,

J.

L.,

Ed.,

Acedemic

Press,

NY,

Chapter

1

(1967)