Creep and Stress Rupture of a Mechanically

Alloyed Oxide Dispersion and Precipitation

Strengthened Nickel-Base Superalloy

T. E. HOWSON, D. A. MERVYN, AND J. K. TIEN

The creep and stress rupture behavior of a mechanically alloyed oxide dispersion

strengthened (ODS) and 7' precipitation strengthened nickel-base alloy (alloy MA 6000E)

was studied at intermediate and elevated temperatures. At 760 ~ MA 6000E exhibits the

high creep strength characteristic of nickel-base superalloys and at 1093 ~ the creep

strength is superior to other ODS nickel-base alloys. The stress dependence of the creep rate

is very sharp at both test temperatures and the apparent creep activation energy measured

around 760 ~ is high, much larger in magnitude than the self-diffusion energy. Stress

rupture in this large grain size material is transgranular and crystallographic cracking is

observed. The rupture ductility is dependent on creep strain rate, but usually is low. These

and accompanying microstructural results are discussed with respect to other ODS alloys

and superalloys and the creep behavior is rationalized by invoking a recently-developed

resisting stress model of creep in materials strengthened by second phase particles. The

analysis indicates that at the intermediate temperature the creep strength is controlled by the

high volume fraction of 7' precipitates and the contribution to the creep strength from the

oxide dispersion is small. At the elevated temperature, the creep strength is derived mainly

from the inert oxide dispersoids.

A recent advance in the development of high temper-

ature alloys has been the incorporation of inert yttrium

oxide dispersoids into a high volume fraction (~50 voI

pct) y' precipitation strengthened nickel-base superalloy

by the mechanical alloying process. 1 The alloy, an

experimental alloy made by the International Nickel

Company and designated MA 6000E, exhibits both the

intermediate temperature strength of a 7' strengthened

superalloy and the elevated temperature strength of an

oxide dispersion strengthened (ODS) alloy, a combi-

nation that makes this superalloy a promising candidate

for advanced turbine applications.

This study examines the creep and stress rupture

behavior of MA 6000E in some detail. Creep testing was

carried out over ranges of applied stresses at 760 and

1093 ~ and the apparent stress and temperature

dependencies of the steady state creep rate and stress

rupture life were determined. While the temperatures

chosen for testing represent possible application tem-

peratures, they were also selected in order to observe

creep in two temperature regimes: one, (760 ~ where

both kinds of strengthening particles should contribute

to the creep resistance, and the second temperature

(1093 ~ where strengthening is expected from only the

inert oxide particles. The results are compared to those

of other particle strengthened systems (both ODS alloys

and conventional nickel-base superalloys) and are cor-

related with microscopic and fractographic observa-

tions. A recent model that mechanistically describes

creep in particle strengthened systems is also used to

discuss and rationalize the experimental results.

T. E. HOWSON and J. K. TIEN are Research Associate and

Professor, respectively, Henry Krumb School of Mines, Columbia

University, New York, NY 10027. D. A. MERVYN, formerly at

Columbia University, is now with Westinghouse Hanford Company,

Richland, WA.

Manuscript submitted July 26, 1979.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURE

Material

Material was provided by NASA-Lewis in the form

of 1 cm diam bar. The nominal composition of the alloy

in weight percent is 15Cr-4.5AI-2.5Ti-2Mo-4W-2Ta-

0.5C-0.15Zr-0.1 B- 1.1Y203--balance nickel. After pow-

der processing by mechanical alloying and consolida-

tion by extrusion, the bar was recrystallized to develop a

coarse elongated grain structure.t It was subsequently

given a three-stage 7' aging heat treatment consisting of

1232 ~ h/Air Cool, then 954 ~ h/Air Cool,

and finally, 843 ~ h/Air Cool.

The macrostructure of MA 6000E was examined in a

Zeiss microscope. All microscopic and fractographic

observations were carried out in a JEOLCO transmis-

sion electron microscope (Model JEM-100CX) oper-

ating in the appropriate transmission or scanning mode.

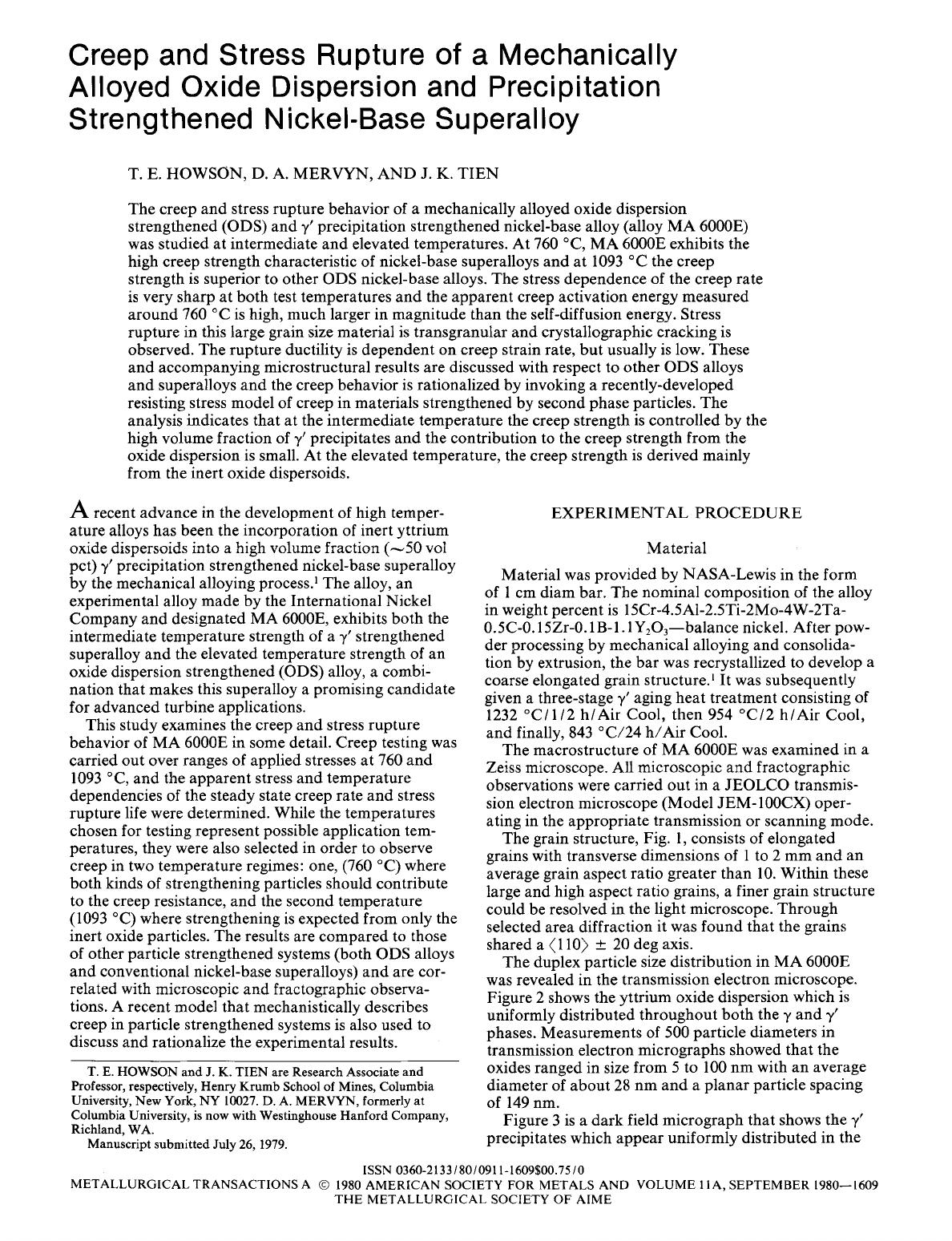

The grain structure, Fig. 1, consists of elongated

grains with transverse dimensions of 1 to 2 mm and an

average grain aspect ratio greater than 10. Within these

large and high aspect ratio grains, a finer grain structure

could be resolved in the light microscope. Through

selected area diffraction it was found that the grains

shared a (110) ___ 20 deg axis.

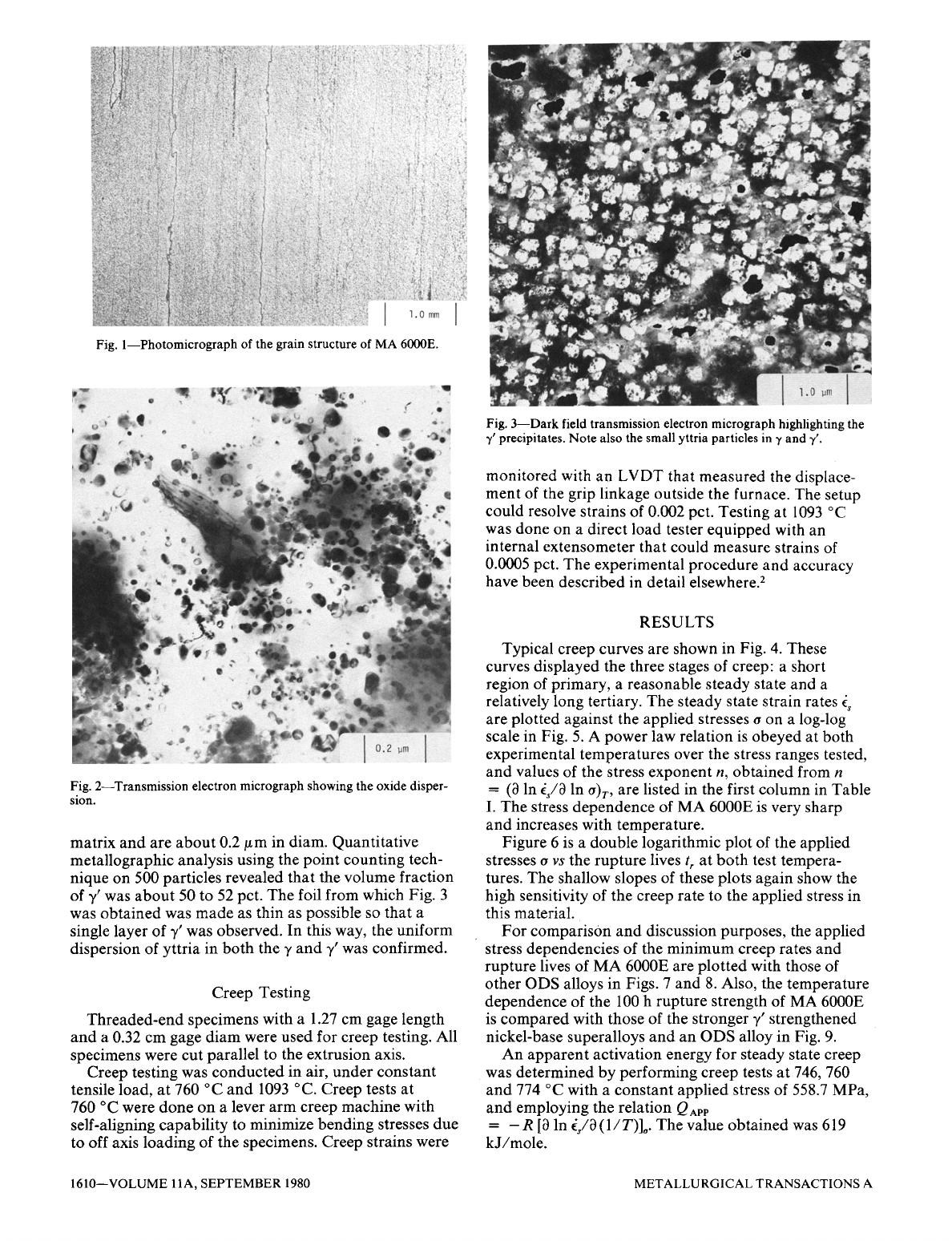

The duplex particle size distribution in MA 6000E

was revealed in the transmission electron microscope.

Figure 2 shows the yttrium oxide dispersion which is

uniformly distributed throughout both the 7 and 7'

phases. Measurements of 500 particle diameters in

transmission electron micrographs showed that the

oxides ranged in size from 5 to 100 nm with an average

diameter of about 28 nm and a planar particle spacing

of 149 nm.

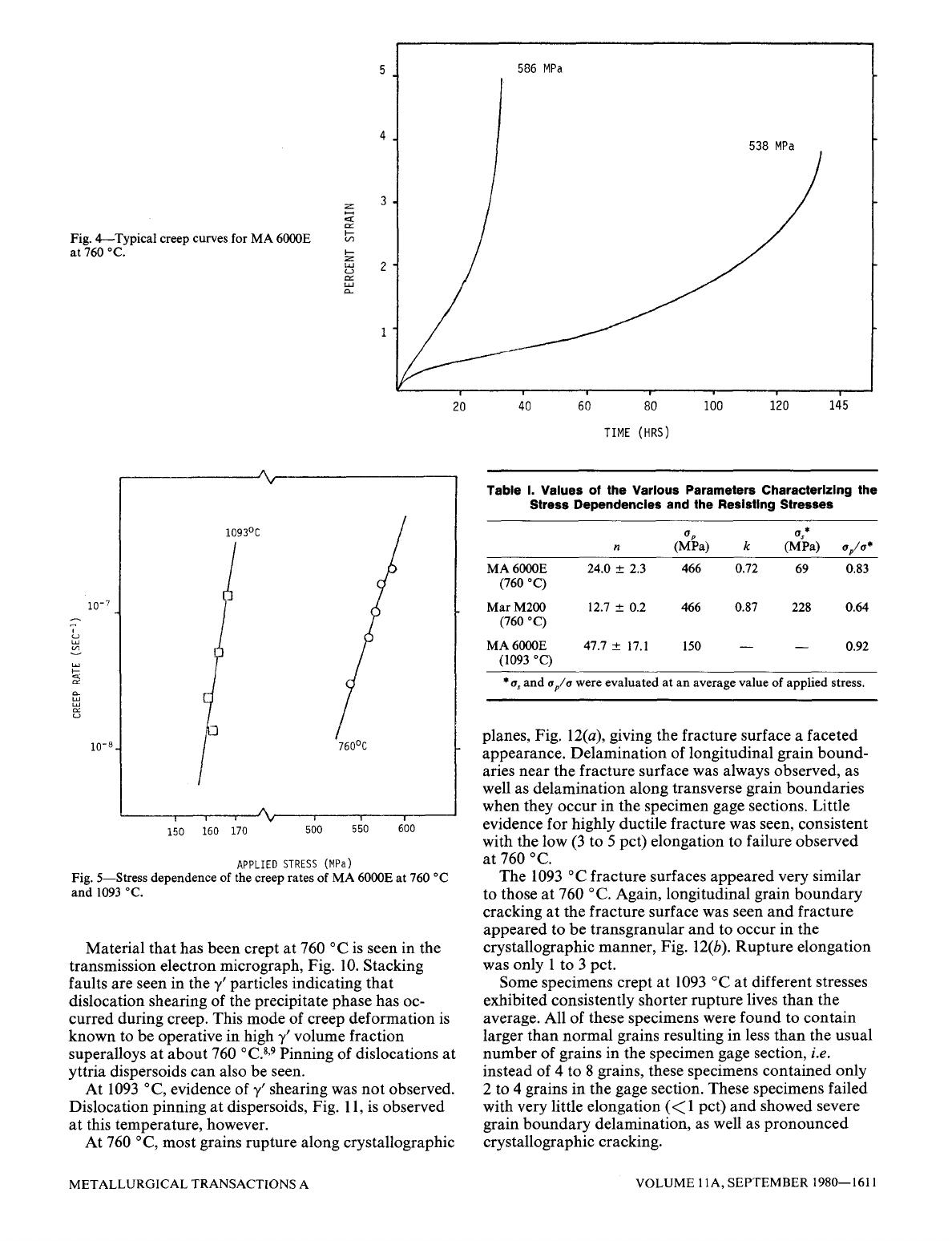

Figure 3 is a dark field micrograph that shows the -{'

precipitates which appear uniformly distributed in the

ISSN 0360-2133/80/0911-1609500.75/0

METALLURGICAL TRANSACTIONS A 9 1980 AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR METALS AND VOLUME 11A, SEPTEMBER 1980--1609

THE METALLURGICAL SOCIETY OF AIME

Fig. 1--Photomicrograph of the grain structure of MA 6000E.

Fig. 2--Transmission electron micrograph showing the oxide disper-

sion.

matrix and are about 0.2/~m in diam. Quantitative

metallographic analysis using the point counting tech-

nique on 500 particles revealed that the volume fraction

of -/was about 50 to 52 pct. The foil from which Fig. 3

was obtained was made as thin as possible so that a

single layer of 7' was observed. In this way, the uniform

dispersion of yttria in both the -/and 7' was confirmed.

Creep Testing

Threaded-end specimens with a 1.27 cm gage length

and a 0.32 cm gage diam were used for creep testing. All

specimens were cut parallel to the extrusion axis.

Creep testing was conducted in air, under constant

tensile load, at 760 ~ and 1093 ~ Creep tests at

760 ~ were done on a lever arm creep machine with

self-aligning capability to minimize bending stresses due

to off axis loading of the specimens. Creep strains were

Fig. 3--Dark field transmission electron micrograph highlighting the

y' precipitates. Note also the small yttria particles in ~, and -/.

monitored with an LVDT that measured the displace-

ment of the grip linkage outside the furnace. The setup

could resolve strains of 0.002 pct. Testing at 1093 ~

was done on a direct load tester equipped with an

internal extensometer that could measure strains of

0.0005 pct. The experimental procedure and accuracy

have been described in detail elsewhere. 2

RESULTS

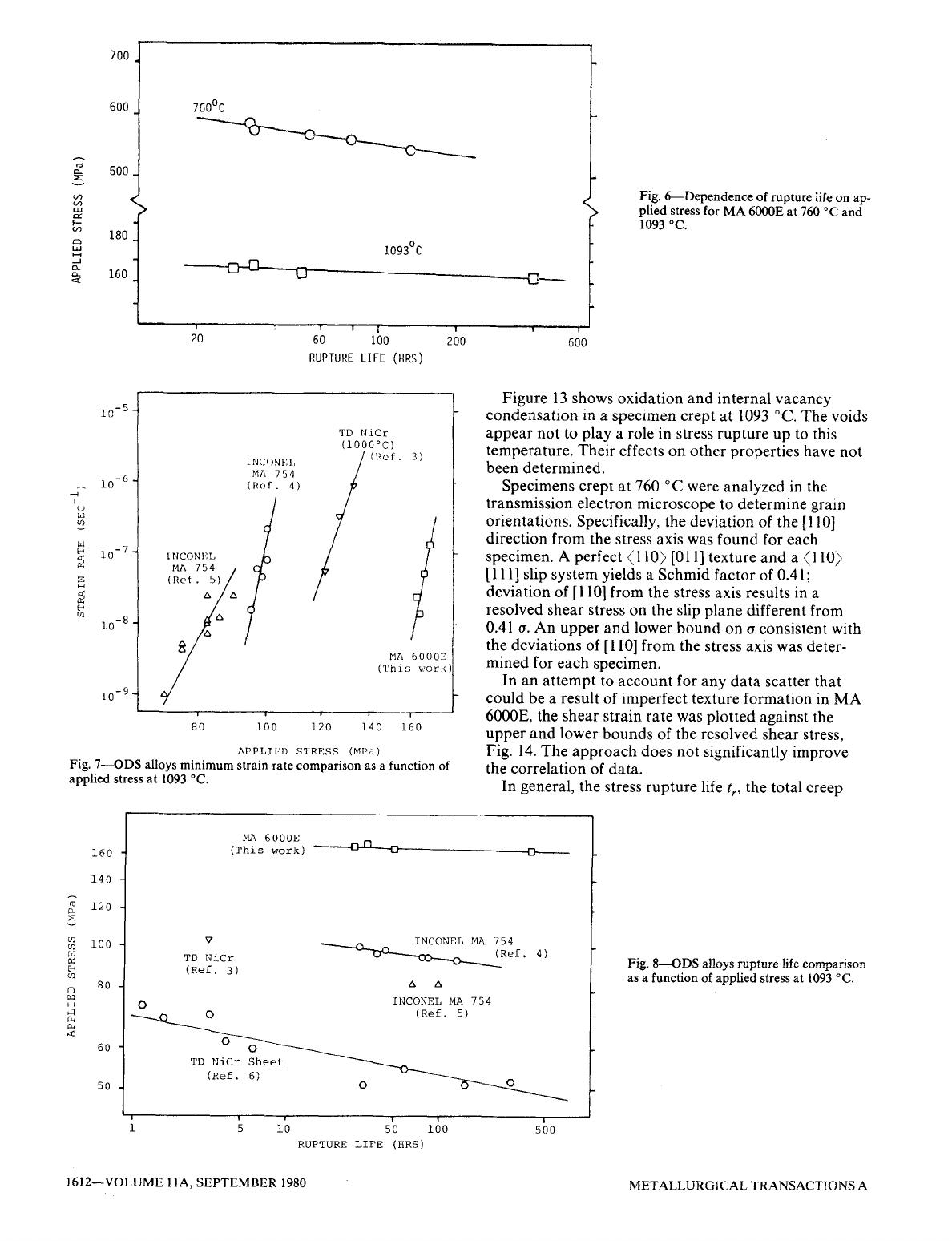

Typical creep curves are shown in Fig. 4. These

curves displayed the three stages of creep: a short

region of primary, a reasonable steady state and a

relatively long tertiary. The steady state strain rates ~,

are plotted against the applied stresses o on a log-log

scale in Fig. 5. A power law relation is obeyed at both

experimental temperatures over the stress ranges tested,

and values of the stress exponent n, obtained from n

= (0 In is/0 In

O)r,

are listed in the first column in Table

I. The stress dependence of MA 6000E is very sharp

and increases with temperature.

Figure 6 is a double logarithmic plot of the applied

stresses o

vs

the rupture lives t r at both test tempera-

tures. The shallow slopes of these plots again show the

high sensitivity of the creep rate to the applied stress in

this material.

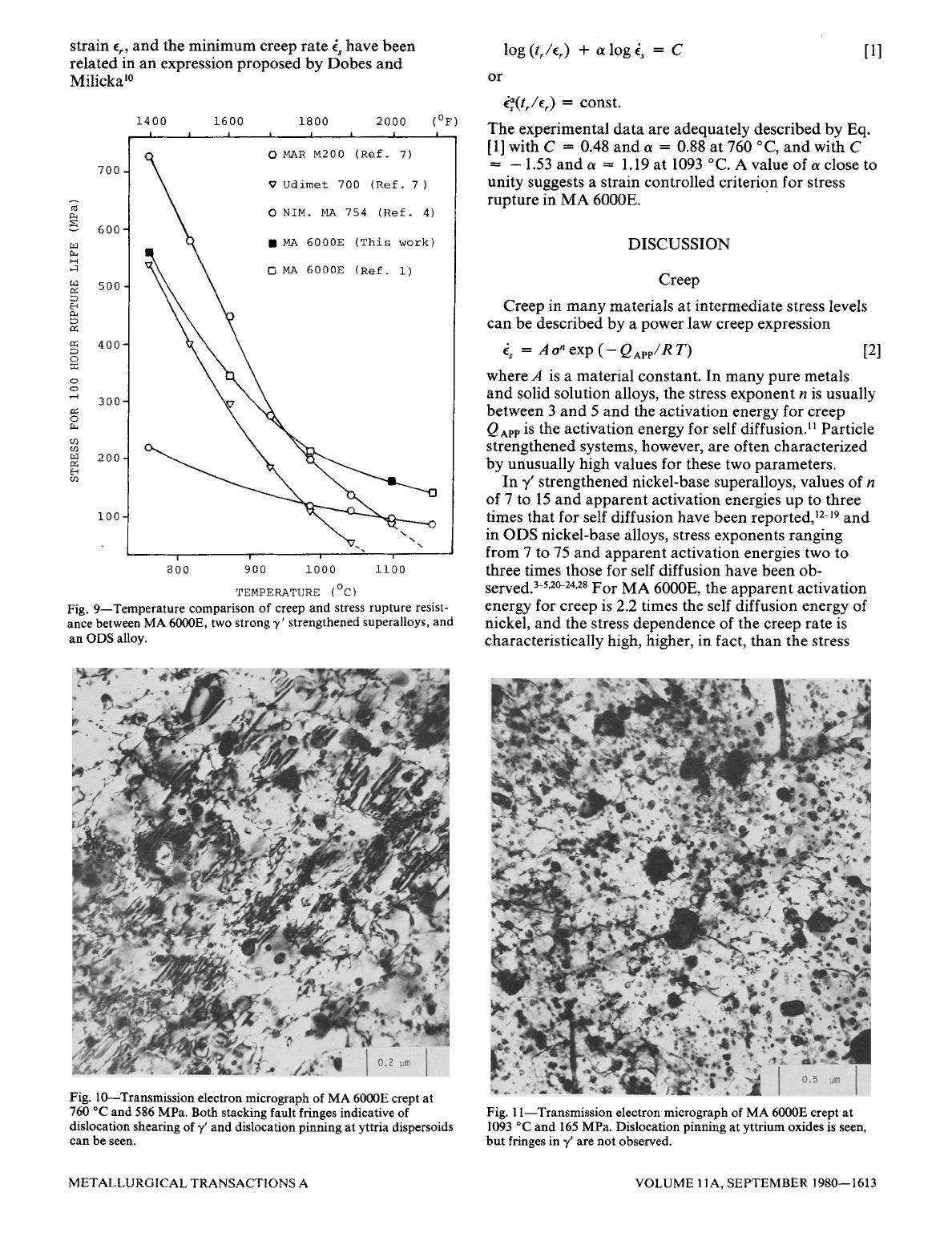

For comparison and discussion purposes, the applied

stress dependencies of the minimum creep rates and

rupture lives of MA 6000E are plotted with those of

other ODS alloys in Figs. 7 and 8. Also, the temperature

dependence of the 100 h rupture strength of MA 6000E

is compared with those of the stronger 7' strengthened

nickel-base superalloys and an ODS alloy in Fig. 9.

An apparent activation energy for steady state creep

was determined by performing creep tests at 746, 760

and 774 ~ with a constant applied stress of 558.7 MPa,

and employing the relation

QAPP

= -R [~ In i,/O (1/T)]o. The value obtained was 619

k J/mole.

1610--VOLUME 11A, SEPTEMBER 1980 METALLURGICAL TRANSACTIONS A

5

I

586 MPa

538 MPa

Fig. 4----Typical creep curves for MA 6000E

at 760 ~

3

,:=C

2

i l ! i' i l

20 40 60 80 100 120 145

TIME

(HRS)

10-7

z"

c,-)

c~

10-8

i093~

t i ~' J i i

150 160 170 500 550 600

(

760Oc

APPLIED STRESS (MPa)

Fig. 5--Stress dependence of the creep rates of MA 6000E at 760 ~

and 1093 ~

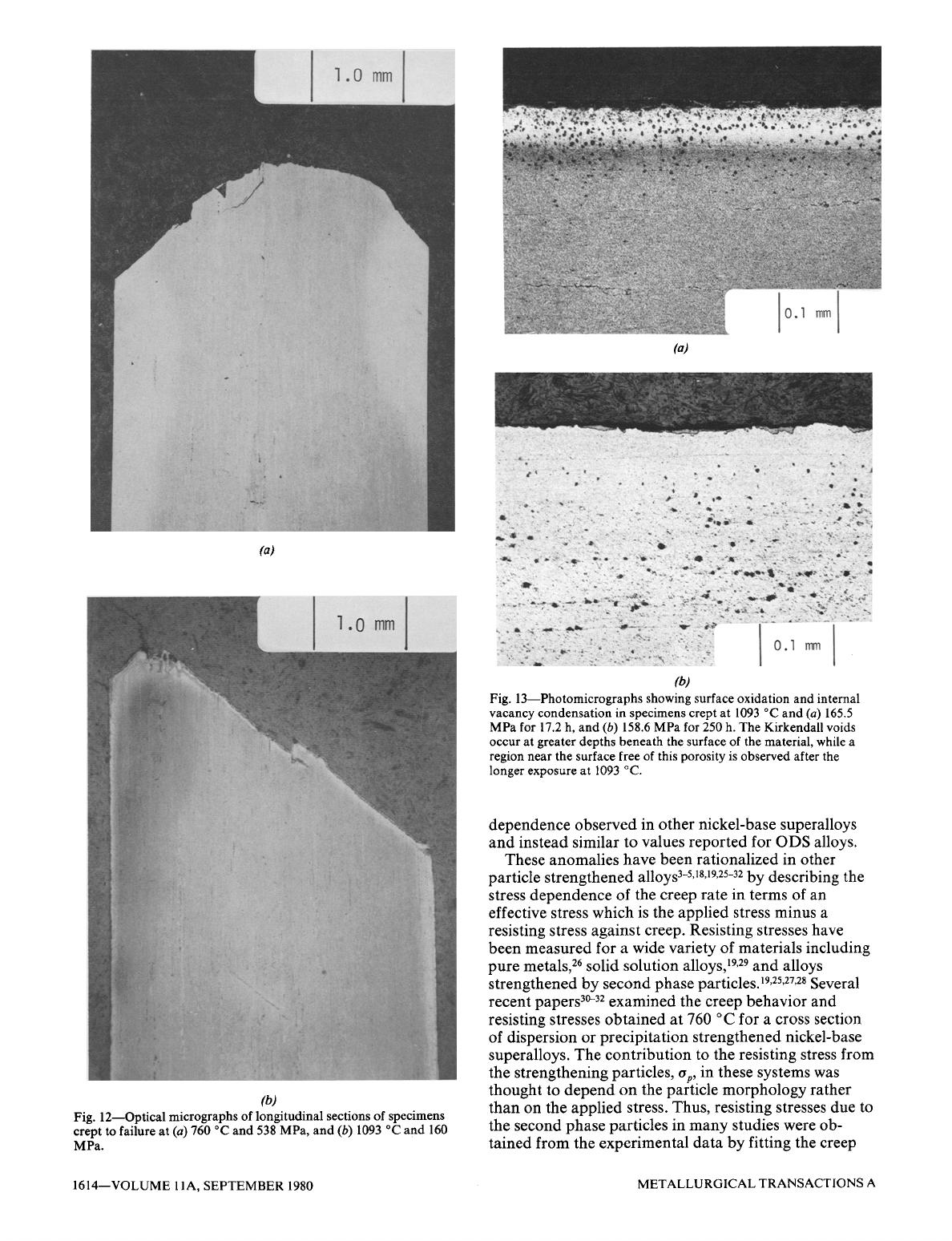

Material that has been crept at 760 ~ is seen in the

transmission electron micrograph, Fig. 10. Stacking

faults are seen in the 3" particles indicating that

dislocation shearing of the precipitate phase has oc-

curred during creep. This mode of creep deformation is

known to be operative in high ~/volume fraction

superalloys at about 760 ~ Pinning of dislocations at

yttria dispersoids can also be seen.

At 1093 ~ evidence of V' shearing was not observed.

Dislocation pinning at dispersoids, Fig. 11, is observed

at this temperature, however.

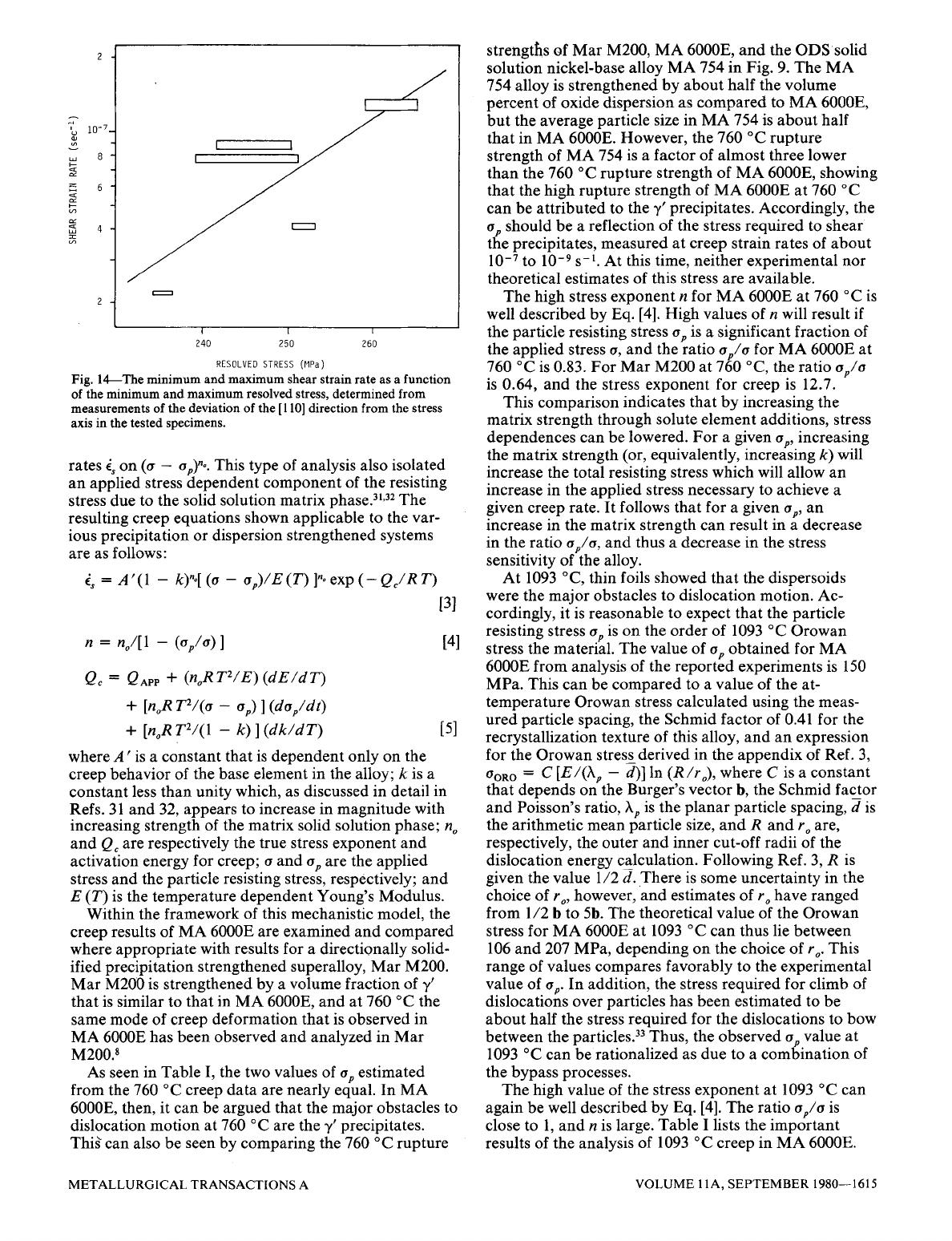

At 760 ~ most grains rupture along crystallographic

Table I. Values of the Various Parameters Characterizing the

Stress Dependencies and the ReslsUng Stresses

op os*

n (MPa) k (MPa) oJo*

MA 6000E 24.0 ___ 2.3 466 0.72 69 0.83

(760 ~

Mar M200 12.7 ___ 0.2 466 0.87 228 0.64

(760 ~

MA 6000E 47.7 _+ 17.1 150 -- -- 0.92

(1093 ~

* o~ and

Oe/O

were evaluated at an average value of applied stress.

planes, Fig. 12(a), giving the fracture surface a faceted

appearance. Delamination of longitudinal grain bound-

aries near the fracture surface was always observed, as

well as delamination along transverse grain boundaries

when they occur in the specimen gage sections. Little

evidence for highly ductile fracture was seen, consistent

with the low (3 to 5 pct) elongation to failure observed

at 760 ~

The 1093 ~ fracture surfaces appeared very similar

to those at 760 ~ Again, longitudinal grain boundary

cracking at the fracture surface was seen and fracture

appeared to be transgranular and to occur in the

crystallographic manner, Fig. 12(b). Rupture elongation

was only 1 to 3 pct.

Some specimens crept at 1093 ~ at different stresses

exhibited consistently shorter rupture lives than the

average. All of these specimens were found to contain

larger than normal grains resulting in less than the usual

number of grains in the specimen gage section,

i.e.

instead of 4 to 8 grains, these specimens contained only

2 to 4 grains in the gage section. These specimens failed

with very little elongation (< 1 pct) and showed severe

grain boundary delamination, as well as pronounced

crystallographic cracking.

METALLURGICAL TRANSACTIONS A VOLUME 11A, SEPTEMBER 1980--1611

v

700

600

50O

180

160

760~

I093~

%

; I

'

i

I

20 60 I00 200

RUPTURE LIFE (HRS)

600

Fig. 6--Dependence of rupture life on ap-

plied stress for MA 6000E at 760 ~ and

1093 ~

I

Lo

z

H

tq

10 -5

10 -6

10 -7

10-8 -

10-9 -

INCONEL

MA 754 /

(Ref. 5)/

-/

[NCONE],

MA 754

( I,te f.

4)

/

TD NiCr

(1000~

Ref. 3)

l

bIA

6000E

(This work

i , , 1

80 100 ]20 ]40 160

APPLTED STRESS (MPa)

Fig. 7--ODS alloys minimum strain rate comparison as a function

of

applied stress at 1093 ~

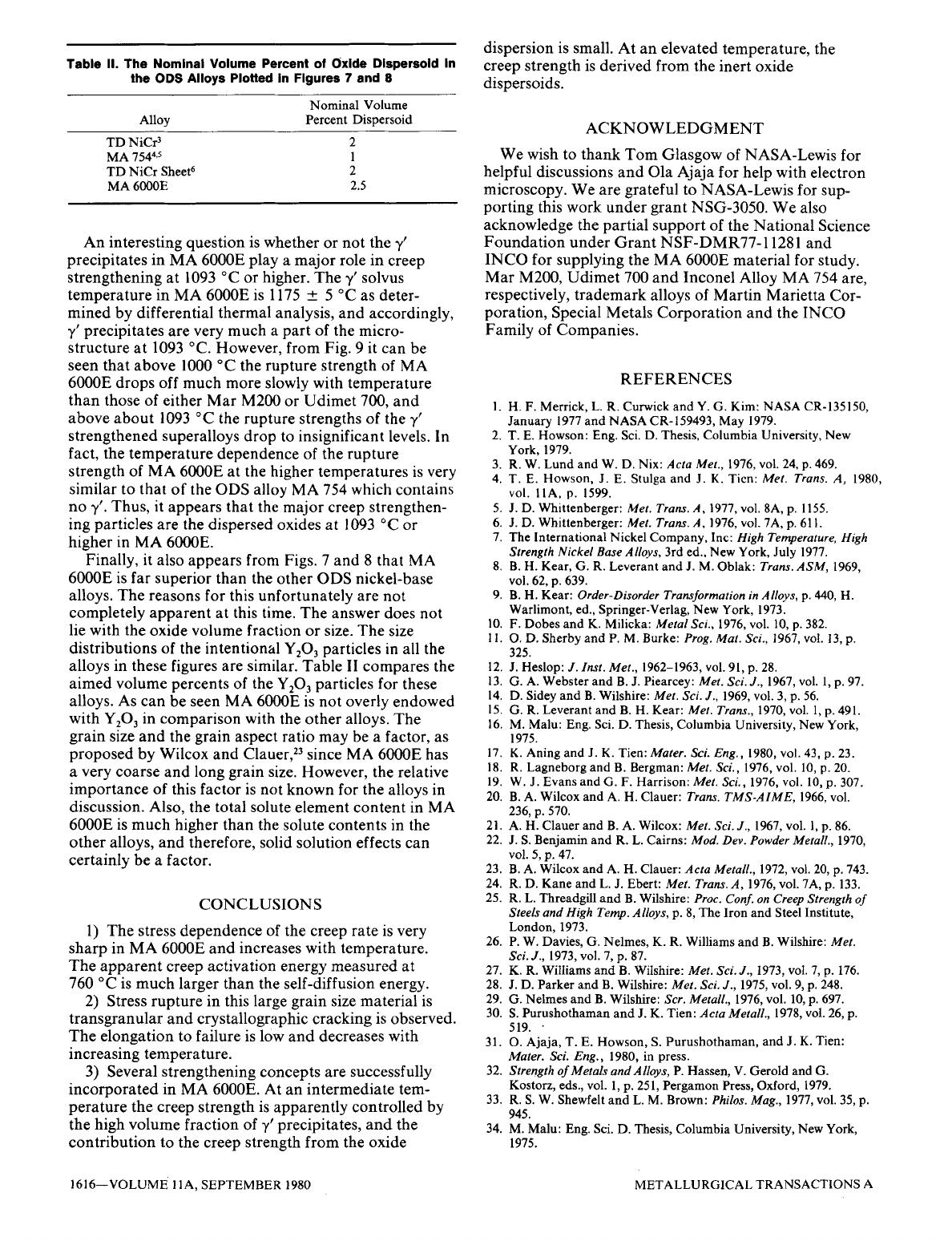

Figure 13 shows oxidation and internal vacancy

condensation in a specimen crept at 1093 ~ The voids

appear not to play a role in stress rupture up to this

temperature. Their effects on other properties have not

been determined.

Specimens crept at 760 ~ were analyzed in the

transmission electron microscope to determine grain

orientations. Specifically, the deviation of the [110]

direction from the stress axis was found for each

specimen. A perfect (110> [011] texture and a (110>

[111] slip system yields a Schmid factor of 0.41;

deviation of [110] from the stress axis results in a

resolved shear stress on the slip plane different from

0.41 o. An upper and lower bound on a consistent with

the deviations of [110] from the stress axis was deter-

mined for each specimen.

In an attempt to account for any data scatter that

could be a result of imperfect texture formation in MA

6000E, the shear strain rate was plotted against the

upper and lower bounds of the resolved shear stress,

Fig. 14. The approach does not significantly improve

the correlation of data.

In general, the stress rupture life t,, the total creep

D~

v

~d

0d

~n

Q

H

0~

<

160

140

120

i00

80

60

50

~ 6000E

(This work) -- f]'gL"-"O- [3"-

V INCONEL MA 754

TD NiCr ~~0~',~ (Ref"

4)

(Ref. 3)

O INCONEL MA 754

(Ref. 5)

o

TD NiCr Sheet

(Ref. 6) O

l ! i ! i

5 i0 50 100 500

RUPTURE LIFE (HRS)

Fig. 8--ODS alloys rupture life comparison

as a function of applied stress at 1093 ~

1612--VOLUME 11A, SEPTEMBER 1980 METALLURGICAL TRANSACTIONS A

strain c,, and the minimum creep rate ~, have been

related in an expression proposed by Dobes and

Milicka m

700

600

H

m 500

E-~

a~ 400'

O

o

"~ 300-

O

o3

o3

200

-

O3

i00-

1400 1600

I I I

1800 2000 (OF

i I A I I

O MAR M200 (Ref. 7)

Udimet 700 (Ref. 7 )

O NIM. MA 754 (Ref. 4)

9 MA 6000E (This work)

O MA 6000E (Ref. i)

I i

i i

800 900 i000 ii00

TEMPERATURE

(~

Fig. 9--Temperature comparison of creep and stress rupture resist-

ance between MA 6000E, two strong 7' strengthened superalloys, and

an ODS alloy.

log(tr/c,) + ctlog~ = C [1]

or

i~(t,/c,)

= const.

The experimental data are adequately described by Eq.

[1] with C = 0.48 and a = 0.88 at 760 ~ and with C

= - 1.53 and a = 1.19 at 1093 ~ A value of a close to

unity suggests a strain controlled criterion for stress

rupture in MA 6000E.

DISCUSSION

Creep

Creep in many materials at intermediate stress levels

can be described by a power law creep expression

~, = A o" exp (-

QAep/R T)

[2]

where A is a material constant. In many pure metals

and solid solution alloys, the stress exponent n is usually

between 3 and 5 and the activation energy for creep

Q Aee is the activation energy for self diffusion.'1 Particle

strengthened systems, however, are often characterized

by unusually high values for these two parameters.

In 7' strengthened nickel-base superalloys, values of n

of 7 to 15 and apparent activation energies up to three

times that for self diffusion have been reported, 12-~9 and

in ODS nickel-base alloys, stress exponents ranging

from 7 to 75 and apparent activation energies two to

three times those for self diffusion have been ob-

served? -5,2~ For MA 6000E, the apparent activation

energy for creep is 2.2 times the self diffusion energy of

nickel, and the stress dependence of the creep rate is

characteristically high, higher, in fact, than the stress

Fig. 10--Transmission electron micrograph of MA 6000E crept at

760 ~ and 586 MPa. Both stacking fault fringes indicative of

dislocation shearing of 7' and dislocation pinning at yttria dispersoids

can be seen.

Fig. 11--Transmission electron micrograph of MA 6000E crept at

1093 ~ and 165 MPa. Dislocation pinning at yttrium oxides is seen,

but fringes in 7' are not observed.

METALLURGICAL TRANSACTIONS A VOLUME 11 A, SEPTEMBER 1980--1613

(a)

(a)

Fig. 13--Photomicrographs showing surface oxidation and internal

vacancy condensation in specimens crept at 1093 ~ and (a) 165.5

MPa for 17.2 h, and (b) 158.6 MPa for 250 h. The Kirkendall voids

occur at greater depths beneath the surface of the material, while a

region near the surface free of this porosity is observed after the

longer exposure at 1093 ~

Fig. 12--Optical micrographs of longitudinal sections of specimens

crept to failure at (a) 760 ~ and 538 MPa, and (b) 1093 ~ and 160

MPa.

dependence observed in other nickel-base superalloys

and instead similar to values reported for ODS alloys.

These anomalies have been rationalized in other

particle strengthened alloys 3-5,18,19,25-32 by describing the

stress dependence of the creep rate in terms of an

effective stress which is the applied stress minus a

resisting stress against creep. Resisting stresses have

been measured for a wide variety of materials including

pure metals, 26 solid solution alloys, 19,29 and alloys

strengthened by second phase particles. 19,25,27,28 Several

recent papers 3~ examined the creep behavior and

resisting stresses obtained at 760 ~ for a cross section

of dispersion or precipitation strengthened nickel-base

superalloys. The contribution to the resisting stress from

the strengthening particles, op, in these systems was

thought to depend on the particle morphology rather

than on the applied stress. Thus, resisting stresses due to

the second phase particles in many studies were ob-

tained from the experimental data by fitting the creep

1614--VOLUME 1 IA, SEPTEMBER 1980 METALLURGICAL TRANSACTIONS A

s-

10_7 .

z 6

4

co

t22222222~

t [ t

240 250 260

RESOLVED STRESS (MPa)

Fig. 14---The minimum and maximum shear strain rate as a function

of the minimum and maximum resolved stress, determined from

measurements of the deviation of the [110] direction from the stress

axis in the tested specimens.

rates ~s on (a - %)"o. This type of analysis also isolated

an applied stress dependent component of the resisting

stress due to the solid solution matrix phase. 3~,32 The

resulting creep equations shown applicable to the var-

ious precipitation or dispersion strengthened systems

are as follows:

i, = A '(1 - k)"o[ (o -

ov)/E

(T) ]"o exp ( -

Q/R T)

[3]

n = no~J1 --

(oJa) ]

[4]

Qc = QAPP +

(no RTz/E) (dE/dT)

+ [noR T2/(a - %) ] (do/dO

+ [noR T2/(1 - k) ] (dk/dT)

[5]

where A ' is a constant that is dependent only on the

creep behavior of the base element in the alloy; k is a

constant less than unity which, as discussed in detail in

Refs. 31 and 32, appears to increase in magnitude with

increasing strength of the matrix solid solution phase;

n o

and Qc are respectively the true stress exponent and

activation energy for creep; • and op are the applied

stress and the particle resisting stress, respectively; and

E (T) is the temperature dependent Young's Modulus.

Within the framework of this mechanistic model, the

creep results of MA 6000E are examined and compared

where appropriate with results for a directionally solid-

ified precipitation strengthened superalloy, Mar M200.

Mar M200 is strengthened by a volume fraction of y'

that is similar to that in MA 6000E, and at 760 ~ the

same mode of creep deformation that is observed in

MA 6000E has been observed and analyzed in Mar

M200. s

As seen in Table I, the two values of % estimated

from the 760 ~ creep data are nearly equal. In MA

6000E, then, it can be argued that the major obstacles to

dislocation motion at 760 ~ are the 3" precipitates.

Thig can also be seen by comparing the 760 ~ rupture

strengths of Mar M200, MA 6000E, and the ODS solid

solution nickel-base alloy MA 754 in Fig. 9. The MA

754 alloy is strengthened by about half the volume

percent of oxide dispersion as compared to MA 6000E,

but the average particle size in MA 754 is about half

that in MA 6000E. However, the 760 ~ rupture

strength of MA 754 is a factor of almost three lower

than the 760 ~ rupture strength of MA 6000E, showing

that the high rupture strength of MA 6000E at 760 ~

can be attributed to the 7' precipitates. Accordingly, the

% should be a reflection of the stress required to shear

the precipitates, measured at creep strain rates of about

10 -7 to 10 -9 s-t. At this time, neither experimental nor

theoretical estimates of this stress are available.

The high stress exponent n for MA 6000E at 760 ~ is

well described by Eq. [4]. High values of n will result if

the particle resisting stress op is a significant fraction of

the applied stress o, and the ratio %/0 for MA 6000E at

760 ~ is 0.83. For Mar M200 at 760 ~ the ratio

%/0

is 0.64, and the stress exponent for creep is 12.7.

This comparison indicates that by increasing the

matrix strength through solute element additions, stress

dependences can be lowered. For a given %, increasing

the matrix strength (or, equivalently, increasing k) will

increase the total resisting stress which will allow an

increase in the applied stress necessary to achieve a

given creep rate. It follows that for a given or, an

increase in the matrix strength can result in a decrease

in the ratio %/o, and thus a decrease in the stress

sensitivity of the alloy.

At 1093 ~ thin foils showed that the dispersoids

were the major obstacles to dislocation motion. Ac-

cordingly, it is reasonable to expect that the particle

resisting stress • is on the order of 1093 ~ Orowan

stress the material. The value of Op obtained for MA

6000E from analysis of the reported experiments is 150

MPa. This can be compared to a value of the at-

temperature Orowan stress calculated using the meas-

ured particle spacing, the Schmid factor of 0.41 for the

recrystaUization texture of this alloy, and an expression

for the Orowan stress derived in the appendix of Ref. 3,

OOR o

= C [E/(~ v -

d)] In

(R/ro),

where C is a constant

that depends on the Burger's vector b, the Schmid factor

and Poisson's ratio, h e is the planar particle spacing, d is

the arithmetic mean particle size, and R and

r o

are,

respectively, the outer and inner cut-off radii of the

dislocation energy calculation. Following Ref. 3, R is

given the value 1/2 d. There is some uncertainty in the

choice of

r o,

however, and estimates of

r o

have ranged

from 1/2 b to 5b. The theoretical value of the Orowan

stress for MA 6000E at 1093 ~ can thus lie between

106 and 207 MPa, depending on the choice of

r o.

This

range of values compares favorably to the experimental

value of op. In addition, the stress required for climb of

dislocations over particles has been estimated to be

about half the stress required for the dislocations to bow

between the particles. 33 Thus, the observed op value at

1093 ~ can be rationalized as due to a combination of

the bypass processes.

The high value of the stress exponent at 1093 ~ can

again be well described by Eq. [4]. The ratio ov/o is

close to 1, and n is large. Table I lists the important

results of the analysis of 1093 ~ creep in MA 6000E.

METALLURGICAL TRANSACTIONS A VOLUME 11A, SEPTEMBER 1980--1615

Table II. The Nominal Volume Percent of Oxide Dlspersold In

the ODS Alloys Plotted in Figures 7 and 8

Nominal Volume

Alloy Percent Dispersoid

TD NiCr 3 2

MA 7544,5 1

TD NiCr Sheet 6 2

MA 6000E 2.5

An interesting question is whether or not the 7'

precipitates in MA 6000E play a major role in creep

strengthening at 1093 ~ or higher. The ,/solvus

temperature in MA 6000E is 1175 _ 5 ~ as deter-

mined by differential thermal analysis, and accordingly,

3" precipitates are very much a part of the micro-

structure at 1093 ~ However, from Fig. 9 it can be

seen that above 1000 ~ the rupture strength of MA

6000E drops off much more slowly with temperature

than those of either Mar M200 or Udimet 700, and

above about 1093 ~ the rupture strengths of the 7'

strengthened superalloys drop to insignificant levels. In

fact, the temperature dependence of the rupture

strength of MA 6000E at the higher temperatures is very

similar to that of the ODS alloy MA 754 which contains

no 3". Thus, it appears that the major creep strengthen-

ing particles are the dispersed oxides at 1093 ~ or

higher in MA 6000E.

Finally, it also appears from Figs. 7 and 8 that MA

6000E is far superior than the other ODS nickel-base

alloys. The reasons for this unfortunately are not

completely apparent at this time. The answer does not

lie with the oxide volume fraction or size. The size

distributions of the intentional Y203 particles in all the

alloys in these figures are similar. Table II compares the

aimed volume percents of the Y203 particles for these

alloys. As can be seen MA 6000E is not overly endowed

with Y203 in comparison with the other alloys. The

grain size and the grain aspect ratio may be a factor, as

proposed by Wilcox and Clauer, 2~ since MA 6000E has

a very coarse and long grain size. However, the relative

importance of this factor is not known for the alloys in

discussion. Also, the total solute element content in MA

6000E is much higher than the solute contents in the

other alloys, and therefore, solid solution effects can

certainly be a factor.

CONCLUSIONS

1) The stress dependence of the creep rate is very

sharp in MA 6000E and increases with temperature.

The apparent creep activation energy measured at

760 ~ is much larger than the self-diffusion energy.

2) Stress rupture in this large grain size material is

transgranular and crystallographic cracking is observed.

The elongation to failure is low and decreases with

increasing temperature.

3) Several strengthening concepts are successfully

incorporated in MA 6000E. At an intermediate tem-

perature the creep strength is apparently controlled by

the high volume fraction of 3" precipitates, and the

contribution to the creep strength from the oxide

dispersion is small. At an elevated temperature, the

creep strength is derived from the inert oxide

dispersoids.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We wish to thank Tom Glasgow of NASA-Lewis for

helpful discussions and Ola Ajaja for help with electron

microscopy. We are grateful to NASA-Lewis for sup-

porting this work under grant NSG-3050. We also

acknowledge the partial support of the National Science

Foundation under Grant NSF-DMR77-11281 and

INCO for supplying the MA 6000E material for study.

Mar M200, Udimet 700 and Inconel Alloy MA 754 are,

respectively, trademark alloys of Martin Marietta Cor-

poration, Special Metals Corporation and the INCO

Family of Companies.

REFERENCES

1. H. F. Merrick, L. R. Curwick and Y. G. Kim: NASA CR-135150,

January 1977 and NASA CR-159493, May 1979.

2. T. E. Howson: Eng. Sci. D. Thesis, Columbia University, New

York, 1979.

3. R.W. Lund and W. D. Nix:

Acta Met.,

1976, vol. 24, p. 469.

4. T. E. Howson, J. E. Stulga and J. K. Tien:

Met. Trans. A,

1980,

vol. IIA, p. 1599.

5. J. D. Whittenberger:

Met. Trans. A,

1977, vol. 8A, p. 1155.

6. J. D. Whittenberger:

Met. Trans. A,

1976, vol. 7A, p. 611.

7. The International Nickel Company, Inc:

High Temperature, High

Strength Nickel Base Alloys,

3rd ed., New York, July 1977.

8. B. H. Kear, G. R. Leverant and J. M. Oblak:

Trans. ASM,

1969,

vol. 62, p. 639.

9. B. H. Kear:

Order-Disorder Transformation in Alloys, p. 440, H.

Warlimont, ed., Springer-Verlag, New York, 1973.

10. F. Dobes and K. Milicka:

Metal Sci.,

1976, vol. 10, p. 382.

11. O. D. Sherby and P. M. Burke:

Prog. Mat. Sci.,

1967, vol. 13, p.

325.

12. J. Heslop:

J. Inst. Met.,

1962-1963, vol. 91, p. 28.

13. G. A. Webster and B. J. Piearcey:

Met. Sci. J.,

1967, vol. 1, p. 97.

14. D. Sidey and B. Wilshire:

Met. Sci. J.,

1969, vol. 3, p. 56.

15. G. R. Leverant and B. H. Kear:

Met. Trans.,

1970, vol. 1, p. 491.

16. M. Malu: Eng. Sci. D. Thesis, Columbia University, New York,

1975.

17. K. Aning and J. K. Tien:

Mater. Sci. Eng.,

1980, vol. 43, p. 23.

18. R. Lagneborg and B. Bergman:

Met. Sci.,

1976, vol. 10, p. 20.

19. W. J. Evans and G. F. Harrison:

Met. Sci.,

1976, vol. 10, p. 307.

20. B. A. Wilcox and A. H. Clauer:

Trans. TMS-A1ME,

1966, vol.

236, p. 570.

21. A. H. Clauer and B. A. Wilcox:

Met. Sci. J.,

1967, vol. 1, p. 86.

22. J. S. Benjamin and R. L. Cairns:

Mod. Dev. Powder Metall.,

1970,

vol. 5, p. 47.

23. B. A. Wilcox and A. H. Clauer:

Acta Metall.,

1972, vol. 20, p. 743.

24. R. D. Kane and L. J. Ebert:

Met. Trans. A,

1976, vol. 7A, p. 133.

25. R. L. Threadgill and B. Wilshire:

Proc. Conf. on Creep Strength of

Steels and High Temp. Alloys,

p. 8, The Iron and Steel Institute,

London, 1973.

26. P.W. Davies, G. Nelmes, K. R. Williams and B. Wilshire:

Met.

Sci.J.,

1973, vol. 7, p. 87.

27. K. R. Williams and B. Wilshire:

Met. Sci. J.,

1973, vol. 7, p. 176.

28. J. D. Parker and B. Wilshire:

Met. Sci. J.,

1975, vol. 9, p. 248.

29. G. Nelmes and B. Wilshire:

Scr. Metall.,

1976, vol. 10, p. 697.

30. S. Purushothaman and J. K. Tien:

Acta Metall.,

1978, vol. 26, p.

519. 9

31. O. Ajaja, T. E. Howson, S. Purushothaman, and J. K. Tien:

Mater. Sci. Eng.,

1980, in press.

32.

Strength of Metals and Alloys,

P. Hassen, V. Gerold and G.

Kostorz, eds., vol. 1, p. 251, Pergamon Press, Oxford, 1979.

33. R. S. W. Shewfelt and L. M. Brown:

Philos. Mag.,

1977, vol. 35, p.

945.

34. M. Malu: Eng. Sci. D. Thesis, Columbia University, New York,

1975.

1616--VOLUME 11A, SEPTEMBER 1980 METALLURGICAL TRANSACTIONS A