Landslides

DOI 10.1007/s10346-020-01451-1

Received: 26 September 2019

Accepted: 28 May 2020

© Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany

part of Springer Nature 2020

Zhichen Song I Xiang Li I José J. Lizárraga I Lianheng Zhao I Giuseppe Buscarnera

Spatially distributed landslide triggering analyses

accounting for coupled infiltration and volume change

Abstract Rainfall infiltration in unsaturated slopes alters the effective

stress through pore water pressure changes, thus causing ground defor-

mation. Although important to assess the timescale over which the

margin of safety of a slope decreases, such coupled processes are rarely

accounted in the context of spatially distributed hazard assessment

procedures. In this paper, a physically based, spatially distributed model

accounting for full hydro-mechanical coupling is discussed. The model

relies on a vectorized finite element (FE) solver to calculate the stability

of deformable unsaturated infinite slopes subjected to transient flow .

First, the FE solver is used to study the response of individual slopes to a

prolonged rainfall for three scenarios (i.e., rigid, swelling, and collapsible

soil). Then, the model is used in the context of spatially distributed

computations to assess spatiotemporal variations of factor of safety over

a large area. For this purpose, a series of shallow landslides occurred in a

mountainous landscape covered by collapsible loess deposits in north-

western China was used as test site. The analyses show that hydro-

mechanical couplings affect the performance of the model in terms of

computed failure time and areal extent of the unstable zones. Specifi-

cally , volume collapse due to suction decrease is found to reduce the

time of failure compared with uncoupled computations obtained for a

rigid soil scenario. The most substantial advantages of using coupled

analyses have been reported with reference to gentle slopes, for which

the higher rate of suction reduction driven by volume change was crucial

to capture landslide source areas that would otherwise be overlooked by

uncoupled analyses. The proposed methodology offers a complete tool

for landslide hazard assessment, in that it incorporates sources of

coupling between hydrology and mechanics that are crucial to replicate

the physics of landslide initiation.

Keywords Hydro-mechanical coupling

.

Infiltration

.

Spatially

distributed analysis

.

Unsaturated soils

.

Collapse

Introduction

Rainfall-induced landslides are among the most widespread and

frequent hazards around the world (Petley 2012). Water infiltration

is indeed a well-known source of soil strength deterioration, either

by increasing pore water pressure (hence reducing the frictional

resistance) or by changing the soil rheology through enhanced

deformability and wetting-induced volume change (Alonso et al.

1990; Rahardjo and Fredlund 1995; Mihalache and Buscarnera

2016). Specifically, as water infiltrates in an unsaturated soil, suc-

tion and degree of saturation vary, eventually giving rise to alter-

ations of the stresses acting on the skeleton and volume changes.

At the same time, changes in the state of saturation controlled by

the volume change response may affect the hydraulic characteris-

tics of the soils, thus influencing the timescale of the infiltration

process and the rate at which deformation and failure may occur

(Wu and Zhang 2009; Garcia et al. 2011; Kim et al. 2016a, b). It is

therefore apparent that, under the most general circumstances,

water infiltration and soil are coupled, in that they affect each

other and determine the hydro-mechanical response of natural

unsaturated soil slopes (Zhang et al. 2005).

Several approaches have been used to evaluate rainfall-induced

landslide hazards at regional scale, such as empirical rainfall threshold

methods (Ti ranti and Rabuffetti 2010;Godtetal.2006; Brunetti et al.

2010;Salciarinietal.2012;DeVitaetal.2013) or statistical and proba-

bilistic methods based on historical records (Ohlmacher and Davis John

2003;Coeetal.2004). Over the last decades, a growing number of

physically based regional models for the assessment of rainfall-induced

landslide susceptibility have also been proposed (Montgomery and

Dietrich 1994;Iverson2000; Salciarini et al. 2008;Baumetal.2010;

Lepore et al. 2012;Parketal.2013;Suetal.2015;Buietal.2017;Zhaoetal.

2019). The recent improvement of the computing performance and the

development of increasingly accessible geographical information system

(GIS) platforms and remote-sensing technology have further contribut-

ed to the widespread use of such physically based models, by making

them increasingly more powerful and reliable for regional-scale land-

slide forecasting. A crucial characteristic of such class of landslide

assessment tools is the simulation of subsurface hydrologic processes

in light of well-defined balance equations and constitutive relations.

Although such models proved useful in several geological settings, they

often recur to simplified descriptions of the soil behavior by neglecting

the deformability prior to failure or hypothesizing frictional slip as the

only mechanism originating instability . However, recent studies on the

mechanics of shallow landslides have shown that volume changes prior

tofrictionalfailureplayacrucialroleforthetriggeringofshallow

landslide in so-called collapsible soil, i.e., deposits which may experience

volume loss upon water infiltration (Buscarnera and Prisco 2012;

Buscarnera and Di Prisco 2013; Lizárraga et al. 2017). Such studies

suggest that neglecting the coupling between water intake and soil

rheology may lead to inaccurate assessments of the rate and magnitude

of the deterioration of the margin of safety during a storm, thus

potentially rendering the analysis unconservative.

The purpose of this paper is to take into account the coupling

between fluid flow and deformation throughout the course of a rain-

storm, thus acknowledging the role of volume changes on the transients

that control the variation of pore pressure within a slope. In standard

uncoupled models, a seepage analysis is used to predict pore water

pressures within a given time, eventually using them as input in stability

calculations (Cai and Ugai 2004;YooandJung2006). In such analyses,

the soil is essentially assumed rigid, in that no soil property enters into

the mass balance equations used to compute pore pressure transients.

Abundant field and laboratory evidence, however, suggests that the

hypothesis of rigid soil during infiltration may be overly restrictive.

For example, T abarsa et al. (2018) conducted a series of collapse poten-

tial tests on loess samples taken from a site susceptible to landslides,

showing a significant risk for wetting-induced collapse. Along the same

lines, Schulz et al. (2018) found a considerable role of swelling in the

dynamics of slow-moving landslides in clay soils subjected to seasonal

rainfall infiltration. In all these cases, it is arguable that the infiltration

processes responsible for the strength deterioration that eventually led

to ground failure took place within deformable soil slopes, thus being

influenced by coupled fluid flow-deformation processes. The impor-

tance of hydro-mechanical couplings has been extensively documented

Landslides

Original Paper

in the context of individual slopes, for which the simultaneous solution

of water mass and momentum balance equations leads to a better

representation of the triggering process (Oh and Lu 2015;Yangetal.

2017;Huetal.2018;Sogaetal.2016). By contrast, no attempts have been

made to explore the impact of hydro-mechanical couplings at the

regional scale, where a more accurate description of pore pressure

transients across a site may lead to substantial improvements of the

landslide susceptibility computations (Lizárraga et al. 2017; Lizárraga

and Buscarnera 2018).

For this purpose, in this paper a physically based model enabling for

coupled hydro-mechanical computations is presented. The model re-

lies on a vectorized finite element (FE) algorithm that combines stabil-

ity analyses for infinite slopes with a transient, one-dimensional

numerical solution of the hydrologic response of layers made of rigid,

swelling, or collapsible soil. For this purpose, a brief description of the

numerical model, as well as of the implementation procedures, is

presented first. Afterwards, the model performance is illustrated with

reference to individual slope units, with the purpose to elucidate

differences between coupled and uncoupled scenarios. Finally , the

model has been tested at the regional scale by using as a reference test

site a series of shallow landslides that took place in northwestern China

across a landscape covered by collapsible loess.

Model description

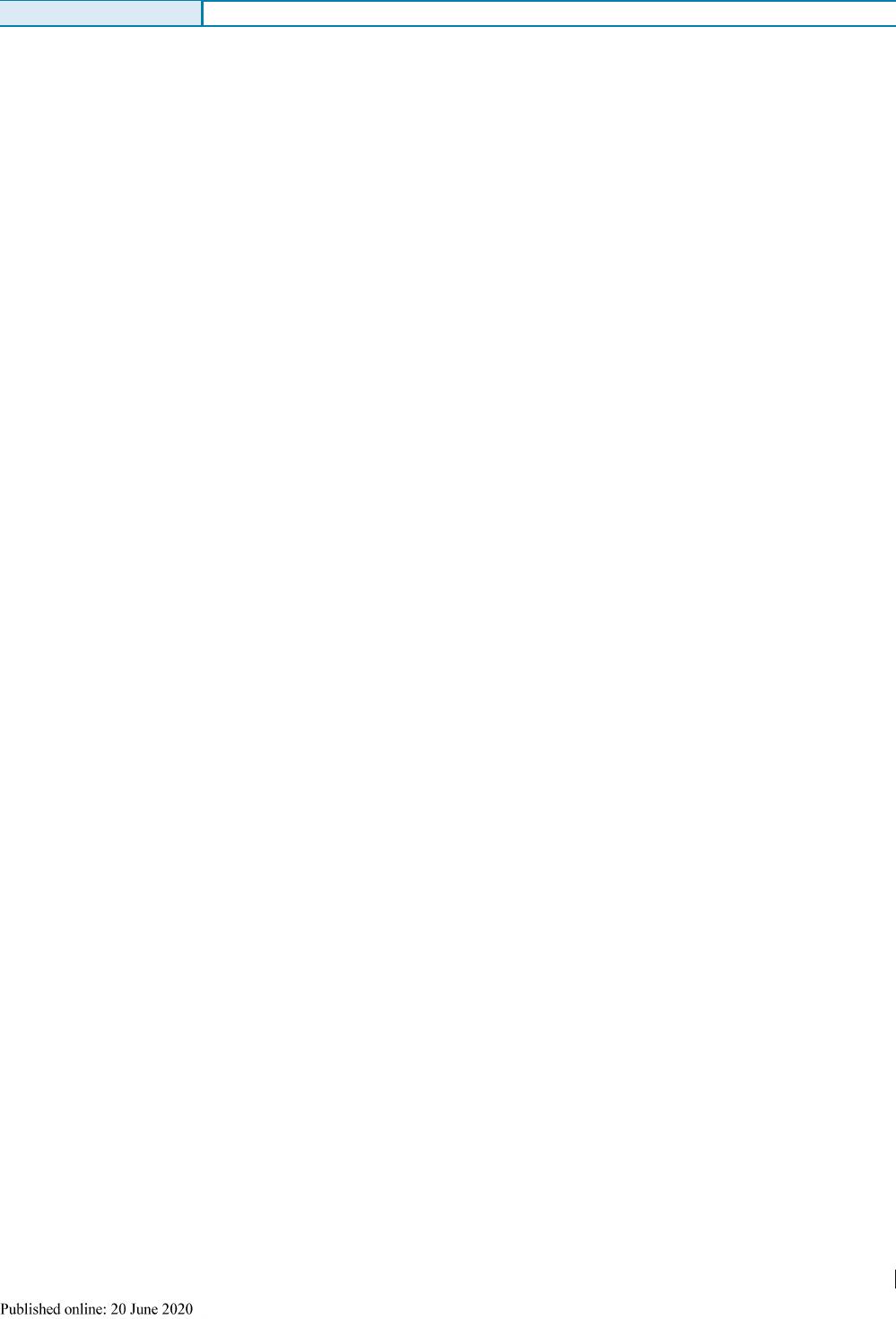

Equilibrium conditions

For an infinite slope as shown in Fig. 1, the balance of lin ear

momentum for an incremental loading process is given by:

∂

˙

σ

z

∂z

þ

˙

γ

s

cosα ¼ 0;

∂

˙

τ

∂z

−

˙

γ

s

sinα ¼ 0 ð1Þ

where α is the slope angle, h the soil thickness, σ

z

the total normal

stress, τ the shear stress, z is the direction normal to the slope, γ

s

the unit weight of the soil, and the upper dot denotes a time

derivative. The constitutive relationships for the soil skeleton are

hypothesized to be governed by the constitutive stress σ′ (Sheng

et al. 2003), which here will be used in a linear elastic context, as

follows:

σ ¼ σ

0

þ χ

k

s ð2Þ

where s is the matric suction and χ

k

is the coefficient that quan-

tifies the effects of suction on the constitutive stress. This stress

formulation is versatile enough to encompass both effective stress

theories (e.g., Khalili and Khabbaz 1998; Lu and Likos 2006) and

approaches based on dual independent variables (Rahardjo and

Fredlund 1995; Alonso et al. 1990 ). For convenience, hereafter the

latter approach will be followed, thus assuming χ

k

= 0. This choice

gives flexibility to incorporate either swelling or collapse into the

flu id flow equations by following the pseudo-elas tic approach

proposed by Lloret et al. (1987). At this reference, it must be noted

that the stress expression in (2) can in principle be used also in

other contexts, and may thus be used in future extensions of the

methodology proposed here. An example is the case of constitutive

laws modeling volume collapse as a plastic phenomenon, either in

the context of effective stress formulations or through double

variable approaches (Buscarnera 2014).

Hydro-mechanical coupling governing equation

Based on water mass balance and Darcy’s law, the governing

equations for 1D hydro-mechanical coupling in unsaturated soils

can be given by (Richards 1931):

n

∂S

r

h

˙

h þ S

r

B

˙

ε ¼ K∇

2

h þ

∂K

∂z

cosα ð3Þ

where h is the water pressure head, ε the normal strain, n the

porosity, S

r

the degree of saturation, B the Biot’s coupling coeffi-

cient, and K the hydraulic conductivity.

The 1D stress -strain relationship associated with the normal

strain can be expressed in increme ntal form as follows (Lloret

et al. 1987):

∂ε

∂t

¼

1

E

∂σ

∂t

þ

1

F

∂s

∂t

ð4Þ

where σ isthenormalnetstress,whileE and F are the elastic

moduli of the soil with respect to changes in the net stresses

and soil suction, respectively. F is negative for collapsible soils,

while is positive for swelling soils. Hereafter, the infilt ration

process is assumed to take place under fixed geometry and

mechanical boundary conditions, thus implying constant total

normal stress. As a result, changes in constitutive stress state

within the unsaturated slope are uniquely related to pore water

pressure (i.e., suction) variation. Under these hypotheses, Eq.

(4) reduces to:

∂ε

∂t

¼

1

F

∂s

∂t

ð5Þ

The mechanical constitutive relations are completed by the

expression linking shear strain and stress, which in a linear elastic

context is given by:

∂γ

∂t

¼

1

G

∂τ

∂t

ð6Þ

where G is the elastic shear modulus.

Based on Eq. (5), combining Eqs. (1) and (3), the system of

coupled partial differential equations (PDEs) can be recast as

follows:

∂

∂y

E

˙

ε

þ

∂

∂y

E

F

˙

s

þ

˙

γ

s

cosα ¼ 0

∂

∂y

G

˙

γ

−

˙

γ

s

sinα ¼ 0

n

∂S

r

h

˙

h þ S

r

B

1

F

∂s

∂t

¼ K∇

2

h þ

∂K

∂z

cosα

ð7Þ

Original Paper

Landslides

Additionally, suitable constitutive relations for the hydraulic

variables have to be defined, by specifying a water retention

curve ( WRC) and a hydraulic conductivity funct ion (HCF).

Hereafter, the Gardner model i s used for both the WRC and

HCF, as follows:

θ hðÞ¼θ

r

þ θ

s

−θ

r

ðÞexp −ahðÞ ð8Þ

KhðÞ¼K

s

exp −ahðÞ ð9Þ

where θ is the volumetric water content; θ

r

and θ

s

are the

residual and saturated volumetric water content, respectively;

K

s

is the hydraulic conductivity at sat urated condition; and a

is a material consta nt that controls the suction sensit ivity of

both hydraulic conductivity and moisture content. Finally, the

initial bounda ry-value problem (IBVP) can be solved by i n-

corporating appropriate initial and b oundary conditions.

Factor of safety

In order to assess stability conditions for an unsaturated slope, the

factor of safety (FS) has to be defined. Although multiple FS

expressions are in principle available, here the following expres-

sion valid for frictional failure will be used (Lizárraga et al. 2017):

FS ¼

tanφ

0

tanα

1 þ

ks

σ

net

ð10Þ

where φ′ and α are friction angle of soil layer and slope angle,

respectively; σ

net

is the net stress and k is the parameter th at

quantifies the effect of suction on the shearing resistance. In other

words, the following analyses postulate two independent contri-

butions in the strength of unsaturated soils, namely f rictional

strength and suction. This approach is consistent with classical

strength criteria for unsaturated soils and implies that the increase

of shear stress at failure scales with suction increments through

the constant coefficient tanφ

b

= k tanφ′ (Fredlund et al. 1978).

Implementation

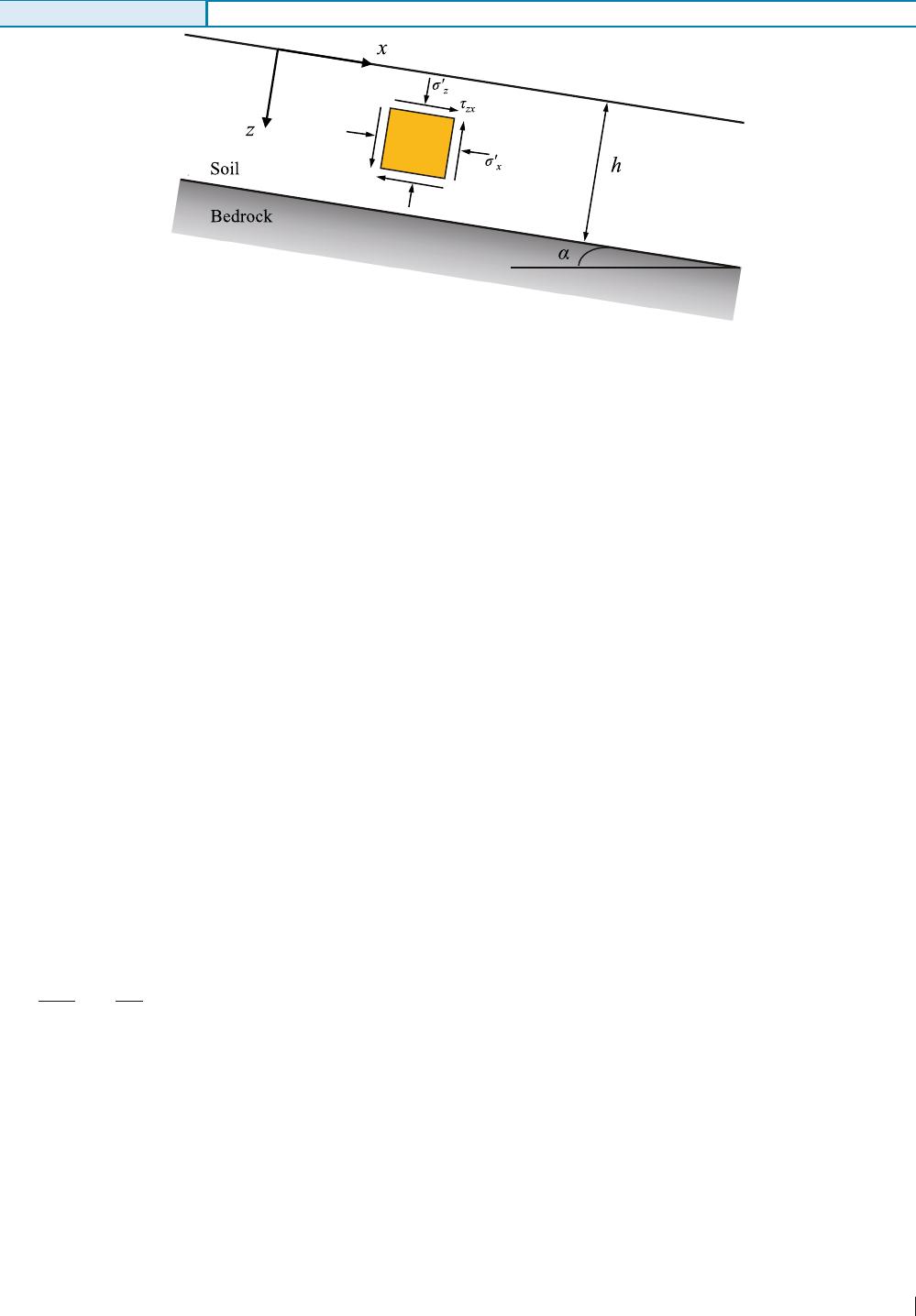

Performing spatially distributed analyses through the

vectorization s cheme proposed by Lizárraga and Buscarnera

(2018) involves three stages, referred to as input, processing, and

output. Here, this procedure has been further elaborated to solve

coupled hydro-mechanical problems at each individual slope unit.

Figure 2 illustrates the methodology. The first step involves a

discretization procedure, by which features of the FE model such

as mesh size and time steps are defined by taking into account the

geometric attributes of the cells of the georeferenced grid (e.g.,

thickness). Then, the slopes of the landscape are arranged into j

subsets sharing the same discretization parameters (marked as j =

1 to 3 in Fig. 2 and denoted by different colors). The vectorized

structure of the selected FE algorithm implies that the computa-

tions are performed simultaneously for all the slope units within a

given subset j. Prior to the processing stage, meshing and time

discretization is assigned to each classified subset (j) to guarantee

reduced computational cost and accuracy.

During the second stage, the pore pressures and correspondent

displacements are computed simultaneously. Next, the computed

pore pressure is used to update FS for each cell in every time step.

If at any time step, the condition FS ≤ 1 is met at certain depth

throughout the analyzed slopes, the corresponding failure time

and depth (t

f

and z

f

) are saved into output column vectors. Oth-

erwise, the program keeps searching until the end of the storm

(which is prescribed as the input loading), eventually assigning a

non-data index to all the cells for which FS > 1 at all the stages of

the analysis.

Finally, the computed output column vectors are mapped back

to the original georeferenced grid by generating raster files for

postprocessing and visualization which can be performed through

a GIS platform.

Based on the abovementioned methodology, soils with different

deformation characteristics can be simulated by switching the sign

of the elastic modul us, F. This is important for slope stability

analyses, in that coupled volume changes during infiltration may

play an opposite role on the margin of safety reflected by the FS

(Wu et al. 2016) or matric suction (Kim et al. 2016a, b). Therefore,

to analyze the role of the hydro-mechanical couplings, three sce-

narios will be considered: (i) an uncoupled model (referred to as

Fig. 1 A homogeneous infinite soil slope and its coordinate system

Landslides

model A), which refers to the case of rigid soil (i.e., F in Eq. (4)is

assumed infinitely large, such that suction changes do not imply

volume change); (ii) a coupled model (referred to as model B)

which refers to the case of swelling soil (F > 0); and (iii) a further

coupled model (referred to as model C) which focuses on the case

of collapsible soil (F < 0).

Single slope response

Before applying the proposed methodology to the selected study

area, single slope analyses have been conducted. The simulations

were based on free drainage conditions at the bottom of the slope

and constant flux prescribed at its, thus enabling to verify our

numerical computations against the analytical results recently

obtained by Wu et al. (2016) with reference to analyses based on

the same boundary conditions.

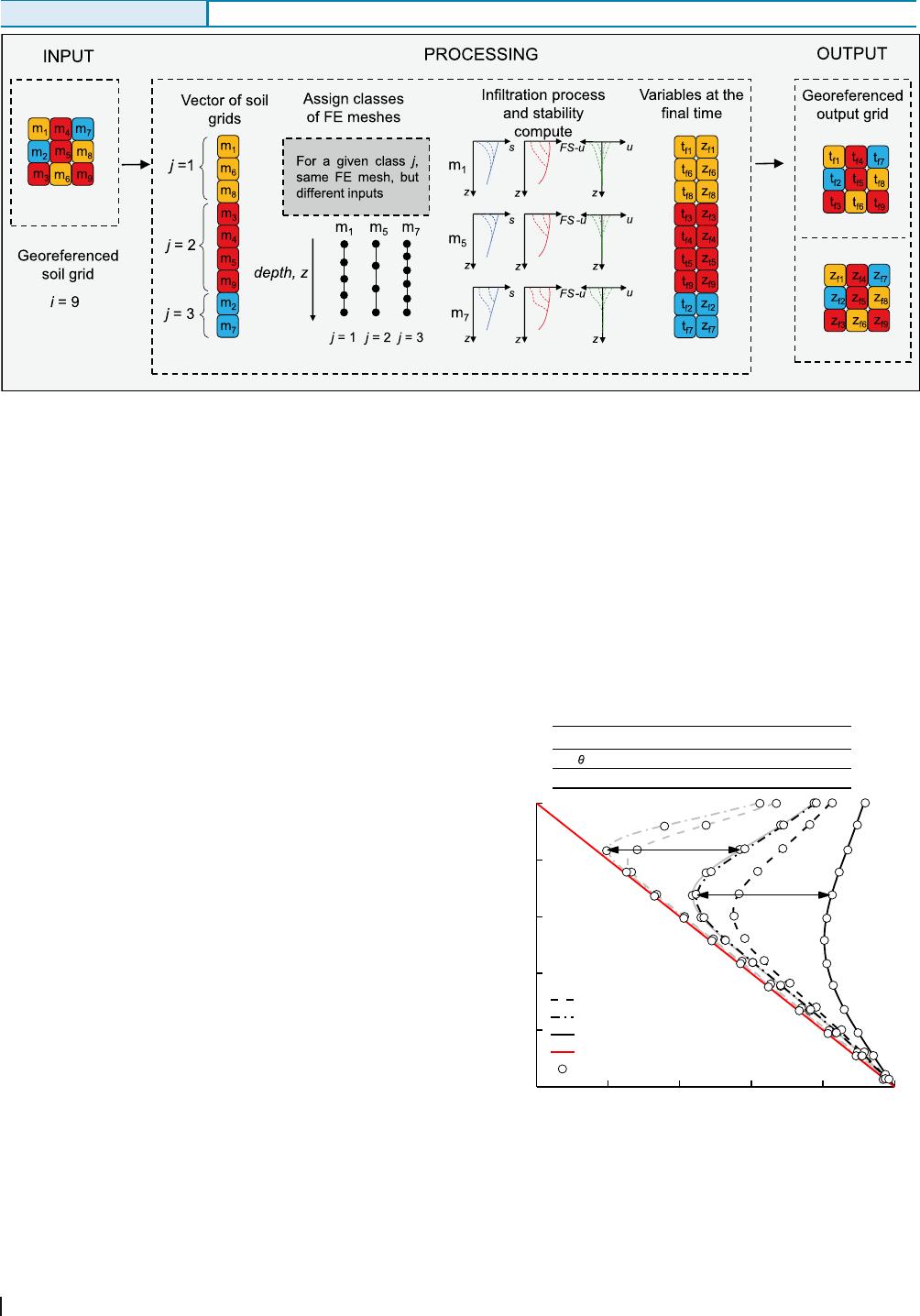

Figure 3 illustrates the variation of the water head during

constant rain infiltration with reference to each of t he three

abovementioned model scenarios. The results of the model have

been validated against the analytical solution proposed by Wu

et al. (2016) for soils characterized by the same material properties

used in the numerical analyses.

The results display perfect match between numerical and

analytical results. Most notably, they show that the proposed

numerical model is a convenient alternative to explore very

general initial and boundary co nditions typical of field settings.

For a given rainfall intensity, higher suction loss corresponds to

higher volume change, everything else being equal. This implies

that more compliant soils will depart more substantially from the

uncoupled scenario A (rigid soil). However, the type of volume

change is also important. In particular, for the coupled model B

(swelling soil) the computed pore water pressure changes are

slower than those obtained with model A. In other words, swell-

ing soils require longer time to experience a suction loss suffi-

cient t o cau se an instab ility. By contrast , coupled mode l C

(collapsible soil) displays faster suction loss than rigid soils

(i.e., model A) and, consequently, enhanced tendency to achieve

instability conditions.

With reference to the set of model parameters discussed earlier,

two monitoring points from a single slope with inclination of 20°

at the depth of 0.5 m and 2 m are selected to illustrate the

computed evolution of key hydro-mechanical variables during

infiltration.

Figure 4a shows the variation of suction for a constant rainfall

input of 10

−6

m/s. Compared with model A, scenario C exhibited a

more pronounced suction loss at the depths of interest, while

model B displayed a relatively slower suction decay. Such effects

can be attributed to deformation-induced couplings. In fact, while

Fig. 2 Schematic representation of model workflow: m = number of cells, j = number of cell classes with the same FE mesh, t

f

= failure time, z

f

= failure depth, s =

suction, FS = factor of safety, u

y

= vertical displacement (modified from Lizárraga and Buscarnera 2018)

Parameters

s

a

k

s

q |F|

0.3

0.01 cm

-1

10

-6

m/s 10

-6

m/s

1000 kPa

-5 -4 -3 -2 -1 0

5

4

3

2

1

Rigid soil (Model A)

Swelling soil (Model B)

Collapsible soil (Model C)

Initial condition (t=0 hr)

Analytical solution (Wu et al., 2016)

t=5 hr

)m(htpeD

Pressure head

(

m

)

t=30 hr

0

Fig. 3 Validation of the numerical model against analytical solutions reported by

Wu et al. (2016). Scenarios relative to rigid, swelling, and collapsing soil are

indicated by different line styles. Computations generated for constant rainfall

(q =10

−6

m/s) imposed during a time interval of 5 h (gray lines) and 30 h (black

lines). Circles indicate the corresponding analytical solution

Original Paper

Landslides

in model B such effect results from the relatively slow suction loss

caused by swelling of the upper layers (which gives rise to a

moderate suction increase beneath this zone to keep con stant

the rate of infiltration), in model C volume loss exacerbates suc-

tion decay, causing stronger downward infiltration even at deeper

locations (depth = 2 m).

In addition, as the soil becomes more saturated, the coupling

effects become less intense and the rate of suction loss follows

similar trends. The sharp decrease of suction computed during

this stage for all the model scenarios correspondingly resulted in a

rapid decrease of FS (Fig. 4b). Although in all simulations, larger

displacements are obtained in the upper portions of the slope due

to higher levels of suction removal, Fig. 4c reveals distinct trends

in soil deformation for the three models, characterized by negative

displacements for model C (volume reduction due to collapse),

positive displacements for model B (volume increase due to swell-

ing), and no displacement during infiltration for model A (rigid

soil). These predictions result from the use of a pseudo-elastic

constitutive law and can be enhanced by using elastoplastic con-

stitutive laws incorporating a more general dependence of the soil

compliance on mean confinement and shear stress (Gens et al.

2006).

Case study

This section discusses the features of a study area in the Xinjiang

province, China , characterized by shallow landslide events that

involved on loess deposits susceptible to volume change. Such

study area will subsequently be used to test the proposed modeling

methodology.

Characteristics of the site

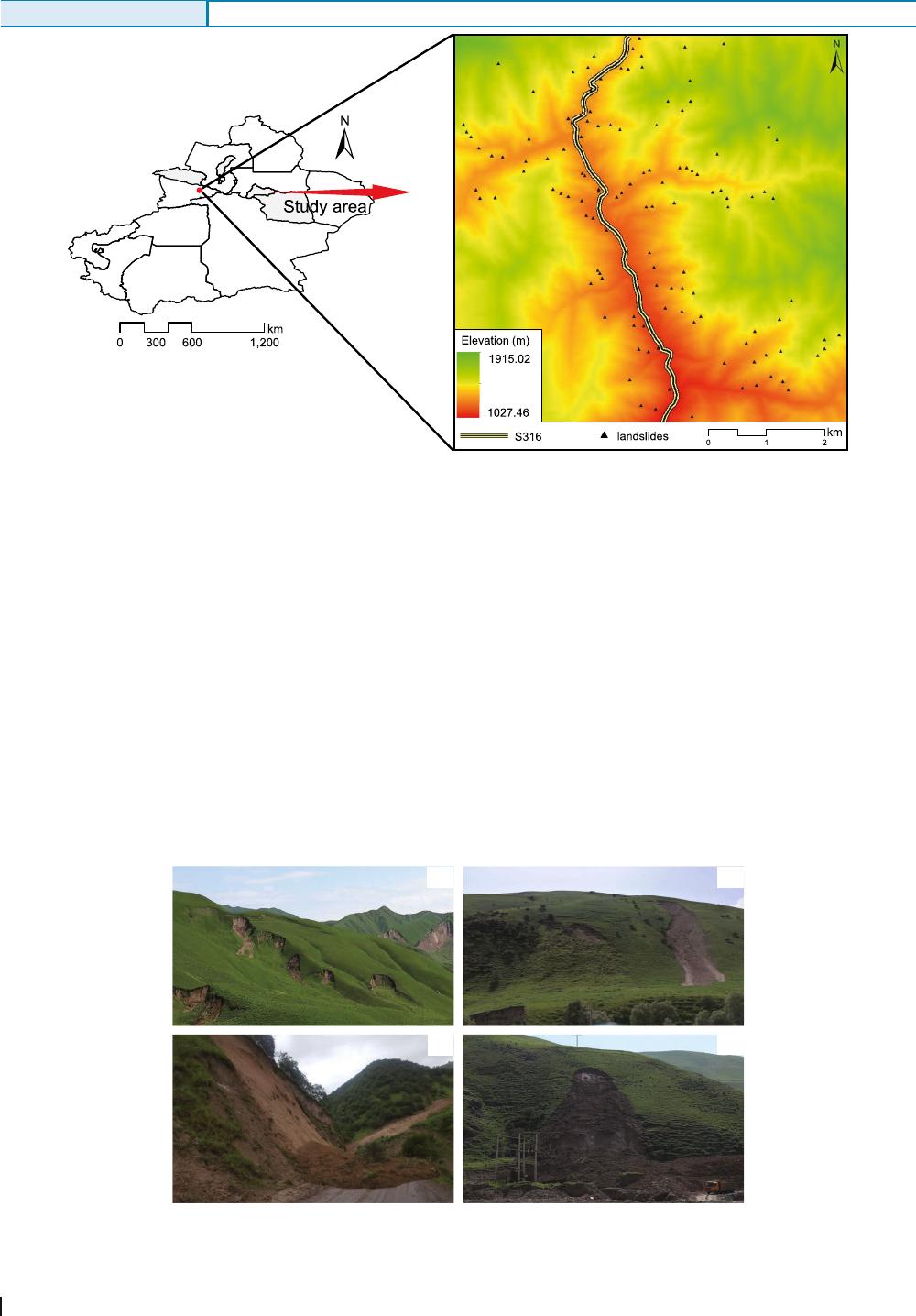

The Yili Kazak autonomous prefecture, in the Xinjiang province, is

one of the seventeen major geological disaster prevention and

control areas listed by the Ministry of Land and Resource. Such

classification is a consequence of the presence of a mountain belt

ab

c

Fig. 4 Evolution of hydro-mechanical variables for different model scenarios: a suction; b FS; and c normal slope deformation

Landslides

covered by highly porous eolian deposits, which characterize the

entire massif of the Yili Kazak region. The area is located alongside

a provincial highway (S316) which connects the Nileke and

Xinyuan county. Construction of highway S316, stretching more

than 28 km, began in April of 2017. The main outcropping geolog-

ical formations along the route are Quaternary Upper Pleistocene

eolian deposits (Q

3

eol

), also called Malan loess, and Upper Pleisto-

cene Holocene alluvial deposits (Q

3-4

apl

) characterized by loose

structure, coarse particles, and development of joint fissures. The

annual precipitation amount is about 477 mm and most precipi-

tation concentrated in April to July (Xinyuan County Meteorolog-

ical Statio n). The hig h frequency of rai nfall and t he poor

mechanical properties of the local soil c aused continuous

landslides since the opening of the infrastructure, threatening

traffic safety and nearby property.

On June 6–7, 2017, after more than 24 h of rainfall (includ-

ing 12 h of heavy precipitation), dozens of shallow landslides

were triggered across the massif covered by loess. The charac-

teristics of the landslides were assessed by the local geological

survey authorities through field investigations (GSR 2017),

based on which the location of the landslide source areas was

mapped across the region of interest (Fig. 5). Figure 6 illus-

trates examples of the typical landslides detected across the

study area. According to the field investigation, most land-

slides failed at a depth lower than 5 m entirely within the

Malan loess strata.

Fig. 5 Location of study area, landslide distribution, and digital elevation model (DEM)

a

b

c

d

Fig. 6 Landslides triggered by heavy rainfall on June 6–7, 2017. The subfigures a–d illustrate examples of the detrimental impacts of landslides on the road safety

(adapted from GSR 2017)

Original Paper

Landslides

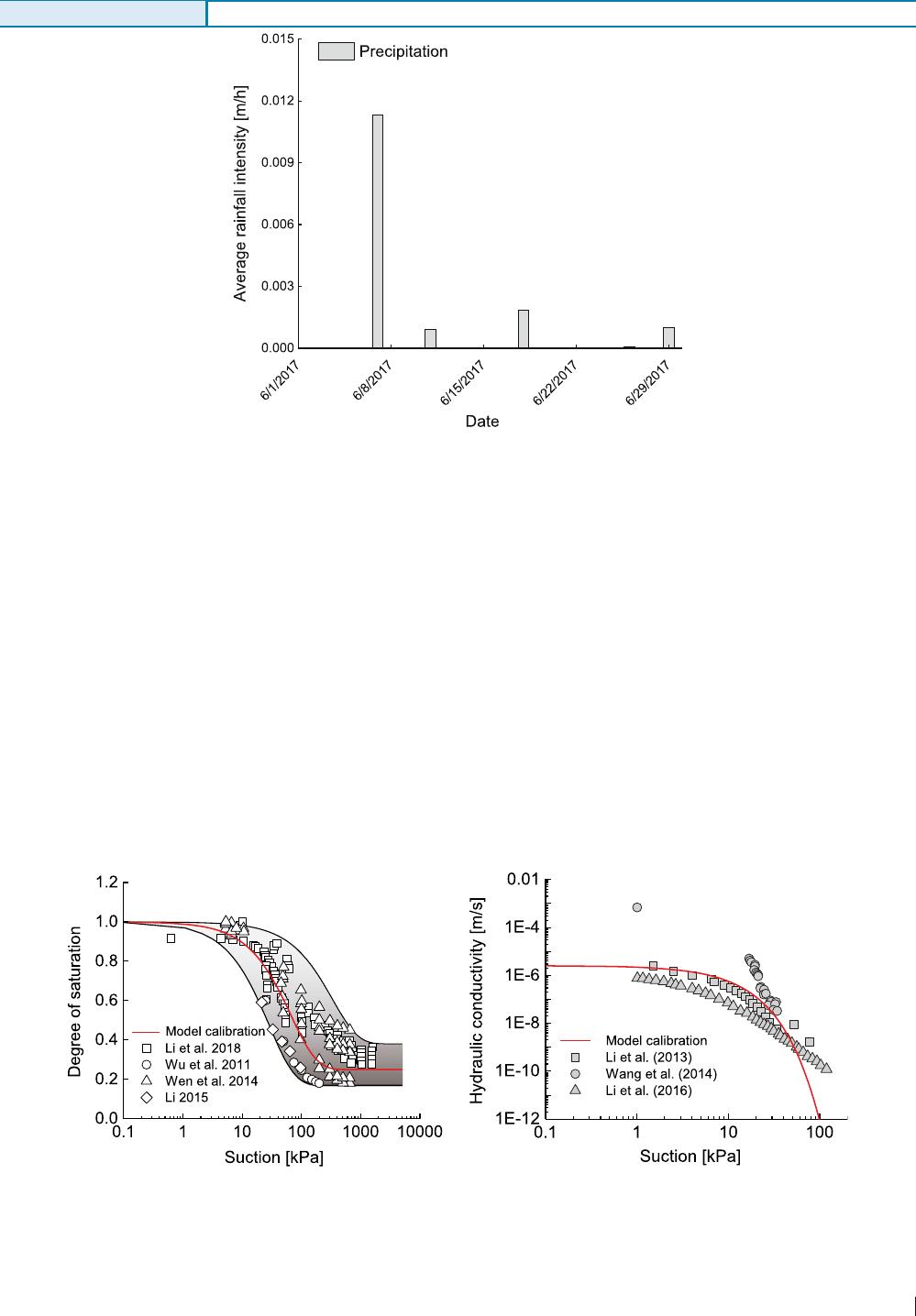

To simulate these events numerically, a georeferenced database

has been created on the basis of these data, as well as of a digital

elevation model (DEM) of 12 × 12 m resolution. In addition, rain-

fall intensity data from national meteorological stations are avail-

able for the study area. Figure 7 provides the average daily rainfall

for the month of June 2017, showing that the event of June 7 was by

far the most intense. The numerical analyses discussed in the

following sections will therefore focus on this specific storm by

using 12-h resolution rainfall measurements according to which

the storm involved a first stage between 8:00 p.m. of June 6 and

8:00 a.m. of June 7, characterized by a relatively low average

intensity of 0.0013 m/h (stage I) and a second stage from

8:00 a.m. to 8:00 p.m. of June 7, characterized by a higher average

intensity of 0. 0213 m/h (stage II), which triggered most of the

reported landslides.

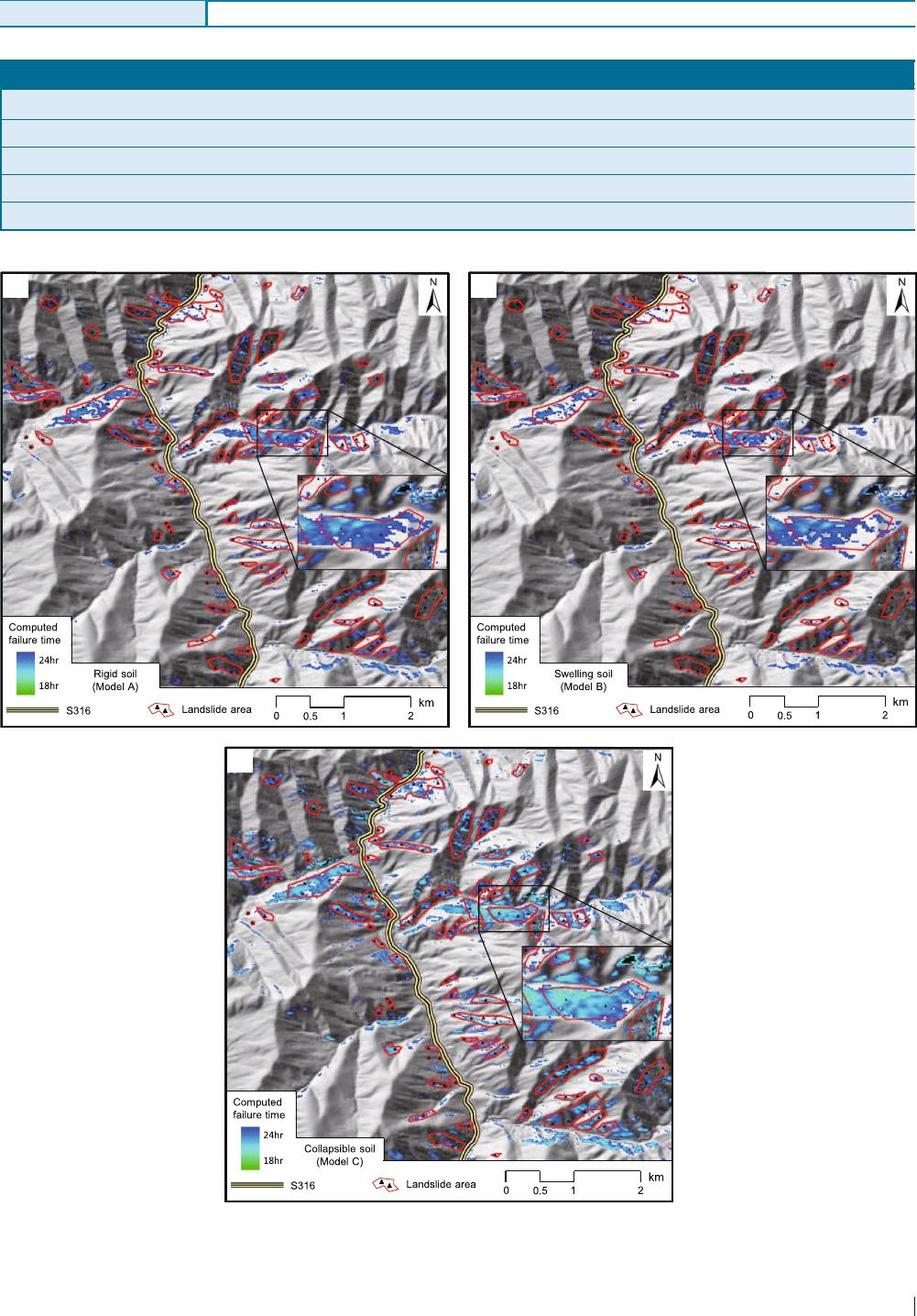

Hydrologic parameters

Initial hydr ological conditions were measured on monitoring

hillslopes within the area and reported in terms of degree of

saturation (GSR 2017). Such monitoring data will be used here

to calculate the initial suction conditions by using a WRC

calibrated for Malan loess. The WRC calibration is shown in

Fig. 8a , along with upper bound and lower bound retentio n

characteristics derived from published experimental data (Li

et al. 2018;Wuetal.2011;Lietal.2015;WenandYan2014).

Despite that the data scatter would suggest the need of site-

specific laboratory measurements here not available, an average

calibration was used to provide a reasonable reference for the

analyses. A calibrated HCF for Malan loess is shown in Fig. 8b,

onthebasisofthesaturatedvalueofK reported by Li et al.

(2016).Itcanbeseenthatsuchcalibrationisinquantitative

Fig. 7 Average daily precipitation intensity during June 2017 in Yili as reported by the China Meteorological Bureau

ab

Fig. 8 Calibration of hydrologic parameters for the Malan loess. a Water retention curve (data after Li et al. 2018; Wu et al. 2011; Li et al. 2015; Wen and Yan 2014). b

Hydraulic conductivity function (data after Li et al. 2013; Li et al. 2016; Wang et al. 2014). Parameter values corresponding to the Gardner model. Experimental data points

are indicated by symbols. Solid lines indicate model results

Landslides

agreement with data for ot her loes s deposits from the area

tested under unsaturated conditions (Li et al. 2013;Wangetal.

2014).

Mechanical parameters

The coefficient k in Eq. (10) controlling the suction dependence of

the shearing resistance has been calibrated by fitting direct shear

test data reported by Hu et al. (2012) (Fig. 9).

The parameter F is a modulus quantifying volume changes caused

by suction variation (i.e., low values reflect high suction sensitivity and

large deformation potential upon wetting). To estimate its value,

oedometer test conducted on Malan loess under different vertical

stress has been used (Shao et al. 2018)(Fig.10). The results show

pressure dependence of F, which exhibits higher magnitude in absolute

value at higher pressure. This indi cates more compliant response and

high suction sensitivity near the surface. The value of F resulting from

the experiments was negative for all the tested conditions, thus

indicating collapsible response. Accordingly, we can infer the modulus

of F at low vertical stress, which led to an estimated value of 998 kPa

for the simulations (the list of calibrated model parameters is summa-

rized in Table 1). It must be noted that, as for all model parameters,

direct evidence specific for samples taken from the study area would

be ideal for quantitative analyses. Since this information was not

available, the estimate derived from the data in Fig. 9 should be

regarded only as a first approximation, which will be assessed against

other model scenarios which will either neglect volume changes (mod-

elA)orassumetheoppositetypeofvolumechangebehavior(i.e.,

swelling, as in model B).

Analyses and results

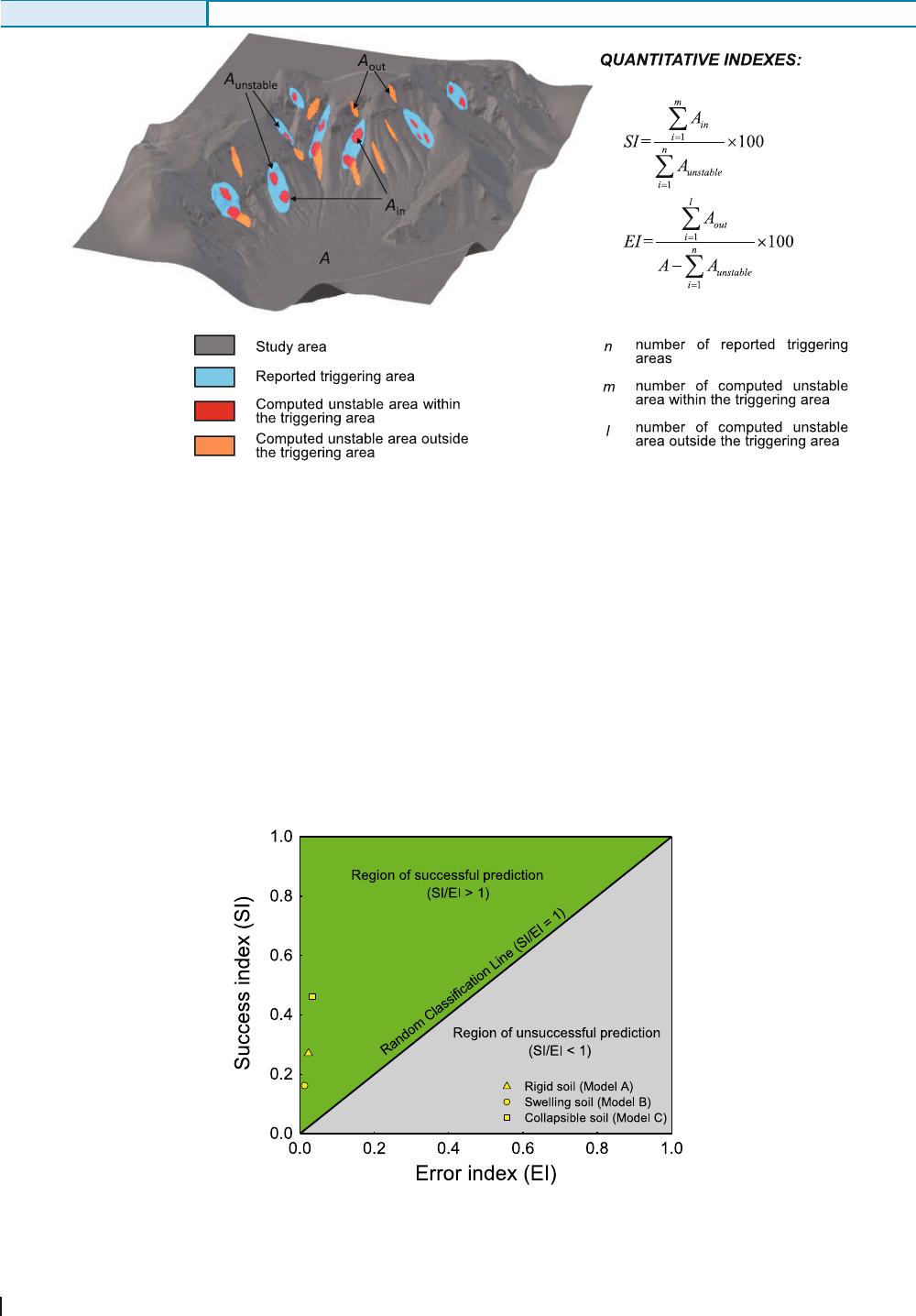

Spatial performance

The computed susceptibility maps based on the calibrated param-

eters summarized in Table 1 are shown in Fig. 11. Cells with distinct

Fig. 9 Calibration of model parameters: coefficient controlling suction-induced strength increase (k = 0.528) (data after Hu et al. 2012)

Fig. 10 Calibration of the elastic modulus F controlling suction-induced volume change (data after Shao et al. 2018); the best fit equation reported in the figure implies a

value of F in kPa units

Original Paper

Landslides

Table 1 Description of model parameters and calibrated values

Hydrologic parameters Value Mechanic parameters Value

Saturated permeability, k

sat

(m/s) 2.6E-6 Friction angle, φ ′ (°) 33

Residual volumetric water content, θ

res

0.115 Elastic moduli, E (kPa) 46,000

Gardner model, α (m

−1

) 0.15 Elastic moduli, |F| (kPa) 998

Unit weight of water, γ

w

(kN/m

3

) 10 Unit weight of soil, γ

s

(kN/m

3

) 15.6

Porosity 0.46 Suction sensitivity of shear strength, k 0.528

a

b

c

Fig. 11 Results of simulations for three model scenarios. a Uncoupled model A. b Coupled model B, swelling soil. c Coupled model C, collapsible soil

Landslides

colors indicate slope failure at different times, thus readily pro-

viding a visual snapshot of the spatial model performances. In

addition, selected locations of the simulated area have been en-

larged to facilitate the visualization of the temporal performance

of the tested models. The map refers to the uncoupled model A

(Fig. 11a), as well as to the coupled models B (Fig. 11b) and C

(Fig. 11c). It is apparent that model C exhibits the highest density of

failure zones across the landscape, while coupled model B predict-

ed the lowest fraction of unstable areas. By contrast, the uncoupled

model A produced intermediate predictions between the two

coupled models. This result is in agreement with earlier analyses

for individual slopes, which showed that volume collaps e was

detrimental for slope stability, while swelling caused delayed suc-

tion removal.

To quantify the accuracy of the computations, two indicators

here defined Success Index (SI) and Error Index (EI) are used to

evaluate the model performance (Sorbino et al. 2007 ). Figure 12

schematically illustrates the definition of such indices. Specifically,

SI represents the portion of computed unstable area that lies

within each source area, while EI represents the percentage ratio

of unstable predictions that lies outside the reported source area

(A

out

) and the area unaffected by the storm (A

stable

). Since high

values of SI are generally accompanied by overprediction, the ratio

SI/EI is used to assess the overall quality of the computation. For

Fig. 12 Schematic diagram of the performance indices definition

Fig. 13 Spatial performance of different model scenarios evaluated through the Success Index (SI) and the Error Index (EI). The light gray area indicates successful

predictions (SI/EI > 1), while the dark gray area indicates poor predictions (SI/EI < 1)

Original Paper

Landslides