Improvement of dielectric properties of ZnO

nanoparticles by Cu doping for tunable microwave

devices

A. Selmi

1,

*, A. Fkiri

2

, J. Bouslimi

3,4

, and H. Besbes

5

1

Laboratory of Materials Organisation and Properties (LR99ES17), Faculty of Sciences of Tunis, University of Tunis, El Manar,

2092 Tunis, Tunisia

2

Lab of Hetero-Organic Compounds and Nanostructured Materials (LR18ES11), Faculty of Sciences of Bizerte, University of

Carthage, 7021 Zarzouna, Tunisia

3

Department of Physics, Faculty of Sciences, Taif University, Taif 888, Saudi Arabia

4

Department of Engineering Physics and Instrumentation, Institute of Applied Sciences and Technology, Carthage University, Tunis,

Tunisia

5

Department of Physics, Faculty of Science, King Abdulaziz University, Jedda, Saudi Arabia

Received: 13 May 2020

Accepted: 4 September 2020

Ó Springer Science+Business

Media, LLC, part of Springer

Nature 2020

ABSTRACT

We report a facile chemical polyol method to synthesize Cu-doped ZnO

nanoparticles with various levels of Cu. X-ray diffraction (XRD), transmission

electron microscopy (TEM), and UV–Visible diffuse reflectance spectroscopy

techniques were used to analyze the structural and optical properties of

Zn

1-x

Cu

x

O nanoparticles. The crystallite size varies between 9.8 and 18.9 nm

and decreased with the increase of Cu doping. The band energy gaps of pure

and Cu-doped ZnO samples are in the range 2.5–3.1 eV. The dielectric prop-

erties, ac conductivity and impedance analysis of Zn

1-x

Cu

x

O nanoparticles

were systematically investigated. It was revealed that the doping of ZnO by Cu

(with low Cu molar content) leads to obtain high dielectric constant and low

tangent loss, which are very encouraging for microwave semiconductor devices.

1 Introduction

In the last years, large bandgap semiconductors such

as WO

3

[1], ZnS [2], GaN [3], and ZnO [4, 5] have

been used in various applications. Among them, the

eco-friendly zinc oxide (ZnO) semiconductor mate-

rial is being one of the preferred materials for many

microelectronics applications due to their excellent

ferroelectric, photoelectric, piezoelectric, catalytic and

dielectric properties [6–11]. Furthermore, ZnO

nanoparticles have received great interest; thanks to

their potential uses in nanotechnology such as lumi-

nescence [12, 13], photo-detection [14, 15], gas sensor

[16, 17] and metal oxide semiconductor (MOS) [18].

Various methods were used to synthesize nanoma-

terials including chemical vapor deposition [19], laser

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10854-020-04408-1

J Mater Sci: Mater Electron

ablation [20], sol gel process [21], solvothermal

method [22, 23], micro-emulsion technique [24],

hydrothermal method [25], and polyol method [26].

Among them, the polyol method is a simple and low-

cost process that allows to produce ZnO nanoparti-

cles with a narrow-size distribution, a controlled

morphology, and a good crystalline quality. The

polyol solvent acts simultaneously as a complexing

agent, a surfactant, and a stabilizing agent, which

lead to avoid the agglomeration of nanoparticles [27].

The photocatalytic and magnetic properties of ZnO

are widely studied in the literature [6–18]. Never-

theless, the dielectric properties of ZnO nanoparticles

are less explored and need to be more investigated.

In recent years, researchers around the world

working on the field of semiconductor-based micro-

electronics are interesting to study the dielectric

properties of ZnO nanoparticles [28, 29]. Currently,

they seek to improve these properties, which will

make these materials good candidates for microelec-

tronic applications. To attain this objective, the con-

trol of the microstructure is important. The dielectric

properties of ZnO nanoparticles could be affected by

doping. Some types of additives or doping have been

employed such as Ni [28], Ag [30], Mn [31], Al [32],

and Co [33]. They greatly affected the dielectric

properties of ZnO nanoparticles. However, the effect

of Cu dopant on the dielectric performances of ZnO

nanoparticles has not been yet reported. Cu

2?

ion has

an ionic radius very close to the Zn

2?

one, which

indicates that Cu

2?

ions can easily enter within ZnO

crystal lattice or substitute Zn

2?

ions in the crystal

and hence can influence the properties of ZnO

properties. With this motivation, we aim in this work

to study deeply the effect of different Cu contents on

the structural, optical, and dielectric properties of

ZnO nanoparticles. Series of Zn

1-x

Cu

x

O nanoparti-

cles with various x values of 0.00, 0.05, 0.10, 0.20 and

1.00% were successfully prepared by polyol process.

2 Experimental

2.1 Synthesis of Cu-doped ZnO

nanoparticles

The preparation of undoped and Cu-doped ZnO

nanoparticles (Zn

1-x

Cu

x

O) was realized according to

a one-pot chemical reaction. Initially, copper chloride

(CuCl

2

; Sigma-Aldrich, purity 99.995%) and zinc

acetate dihydrate (Zn(OAc)

2

.2H

2

O; Sigma-Aldrich,

purity C 98%) were simultaneously mixed in 50 ml

of ethylene–glycol (EG) solvent. The contents of Cu

element are equal to 0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2 and 1%. The

mixture was maintained under reflux for 60 min at

160 °C. The sequential reactions were thermally

controlled. Then, the attained precipitate was cen-

trifuged at 8000 rpm, washed several times (3–5

times) with ethanol, and finally dried at 100 °C for

12 h to get the final Zn

1-x

Cu

x

O powder (white color).

2.2 Characterization techniques

The structural analysis of prepared Zn

1-x

Cu

x

O

nanoparticles was characterized by X-ray diffraction

technique using a Bruker X-ray diffractometer with

Cu K

a1

radiation (k = 1.5406 A

˚

).The crystallites size

of Zn

1-x

Cu

x

O nanoparticles was calculated by

employing the Scherrer equation. The microstructure

observations were performed by transmission elec-

tron microscopy (TEM, JEOL 2100F). The optical

absorption spectra were recorded using Varian

CARY 100 Scan UV–visible diffuse reflectance spec-

trophotometer (UV–vis DRS). The dielectric proper-

ties of Zn

1-x

Cu

x

O nanoparticles were measured over

a wide frequency range (1 to 10

5

Hz) using a Solar-

tron 1260A (Impedance/Gain-Phase Analyzer) cou-

pled with 1296 Dielectric Interface.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Characterization of Zn

12x

Cu

x

O

nanoparticles

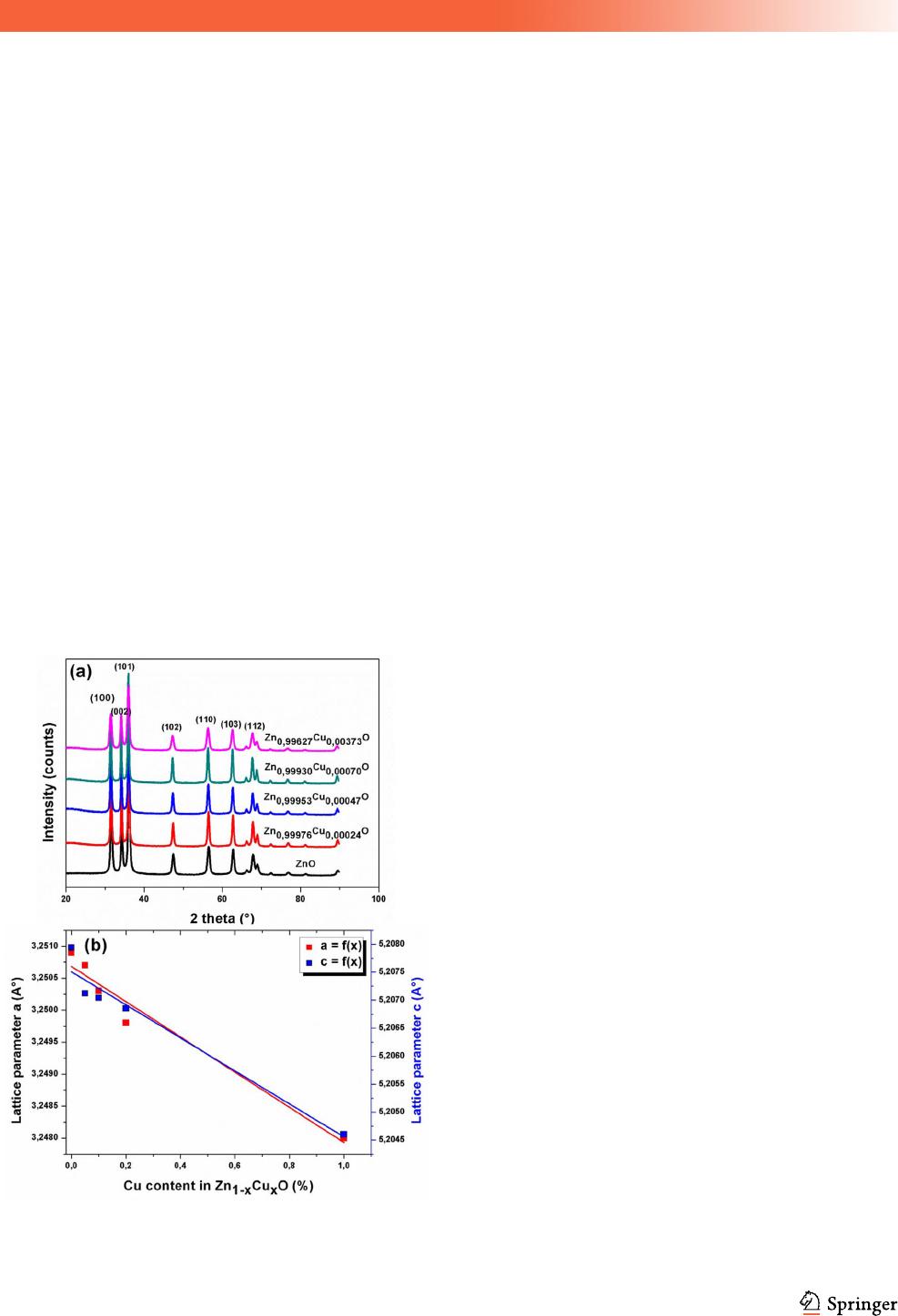

The crystalline phase of the prepared Zn

1-x

Cu

x

O

nanoparticles was studied by XRD. Figure 1a illus-

trates the XRD patterns of Cu-doped ZnO (Zn

1-x-

Cu

x

O; where x = 0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2 and 1). All the

diffraction peaks are indexed by the hexagonal

Wurtzite ZnO with the intense (100), (002) and (101)

characteristic peaks (space group P63mc, JCPDS No.

36-1451). The large peaks in XRD patterns indicate

that very small nanocrystals are present in the sam-

ple. The lattice parameters of the five elaborated

samples were determined by Rietveld process using

the FULLPROF program [34].The different structural

parameters of various synthesized Zn

1-x

Cu

x

O

nanoparticles including, lattice parameters, cell vol-

ume, and BET-specific surface area as a function of

J Mater Sci: Mater Electron

Cu concentration are summarized in Table1. The

deduced lattice parameters (a and c) decrease with

increasing the concentration of Cu dopant [35]. A

very small variation in the lattice parameters ‘a’ and

‘c’ is observed (Fig. 1b). This is due to the very close

values ionic radii of Cu

2?

(0.57 A

˚

) and Zn

2?

(0.60 A

˚

)

ions [36].

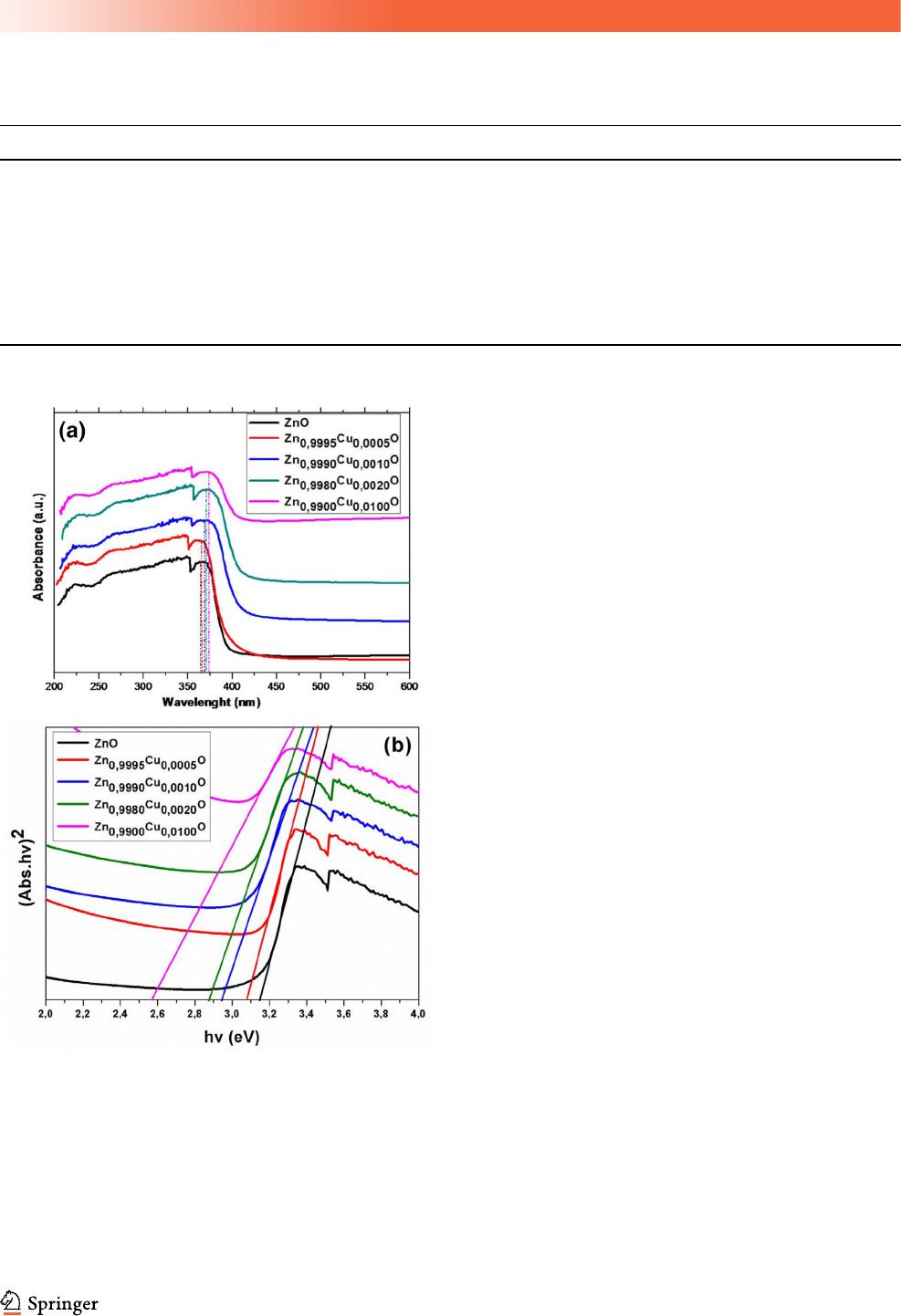

Figure 2a shows the UV–vis DRS spectra of

Zn

1-x

Cu

x

O nanoparticles. We note that the strong

absorption edge occurs in the UV light area, which is

a typical optical absorption behavior of Cu-doped

ZnO semiconductor compounds. It can be seen from

Fig. 2a that the maximum of the absorbance band

shifts slightly toward higher wavelength owing to Cu

doping. This could be mainly due to the strong

interaction between the surface oxides of Cu and Zn

[37]. The optical bandgap can be calculated from the

Tauc plot (variation of (Abs.E)

2

as a function of

photon energy E, where Abs is the absorbance) [38].

As shown in Fig. 2b, the optical bandgap obtained

from the intersection of the sharply decreasing lines

with the energy axis is 3.16, 3.08, 2.94, 2.88, and

2.57 eV for x = 0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2 and 1, respectively

(Table 1). The obtained values confirm the quantum

confinement regime of the Cu–doped nanoparticles.

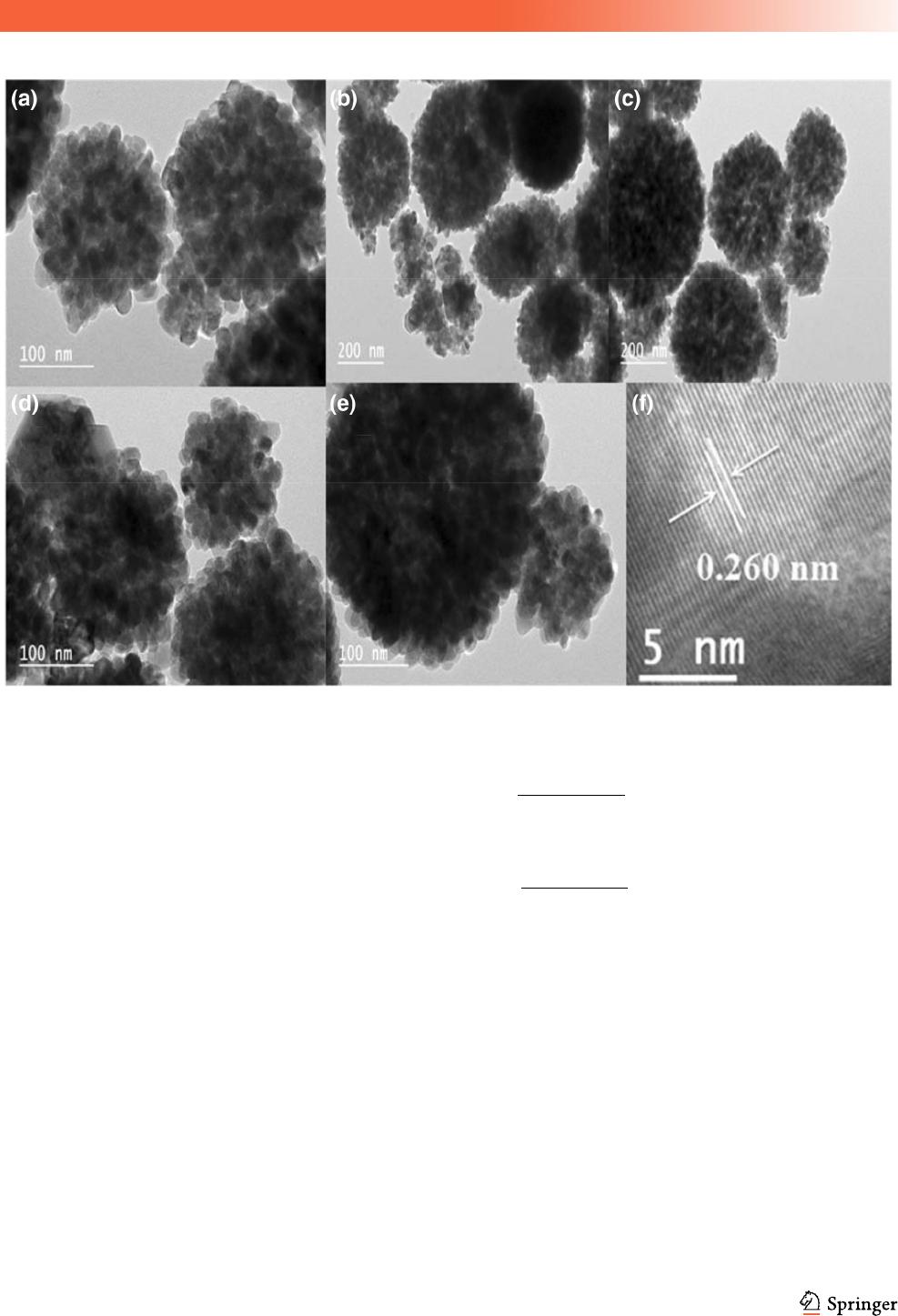

Figure 3a–f depict the TEM images obtained for

various Zn

1-x

Cu

x

O nanoparticles. TEM images

showed spherical-shaped nanoparticles with size

ranging between 9 and 20 nm (Fig. 3a–e). Figure 3f

shows a high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) micrograph

of the Zn

1-x

Cu

x

O nanoparticles with x = 0.1%. The

analysis indicates the well-defined ZnO crystal

planes, thus approving the crystalline structure of the

formed nanoparticles. The interplanar spacing of the

ZnO (002) atomic plane is 0.26 nm, which is consis-

tent with the wurtzite structure [39].

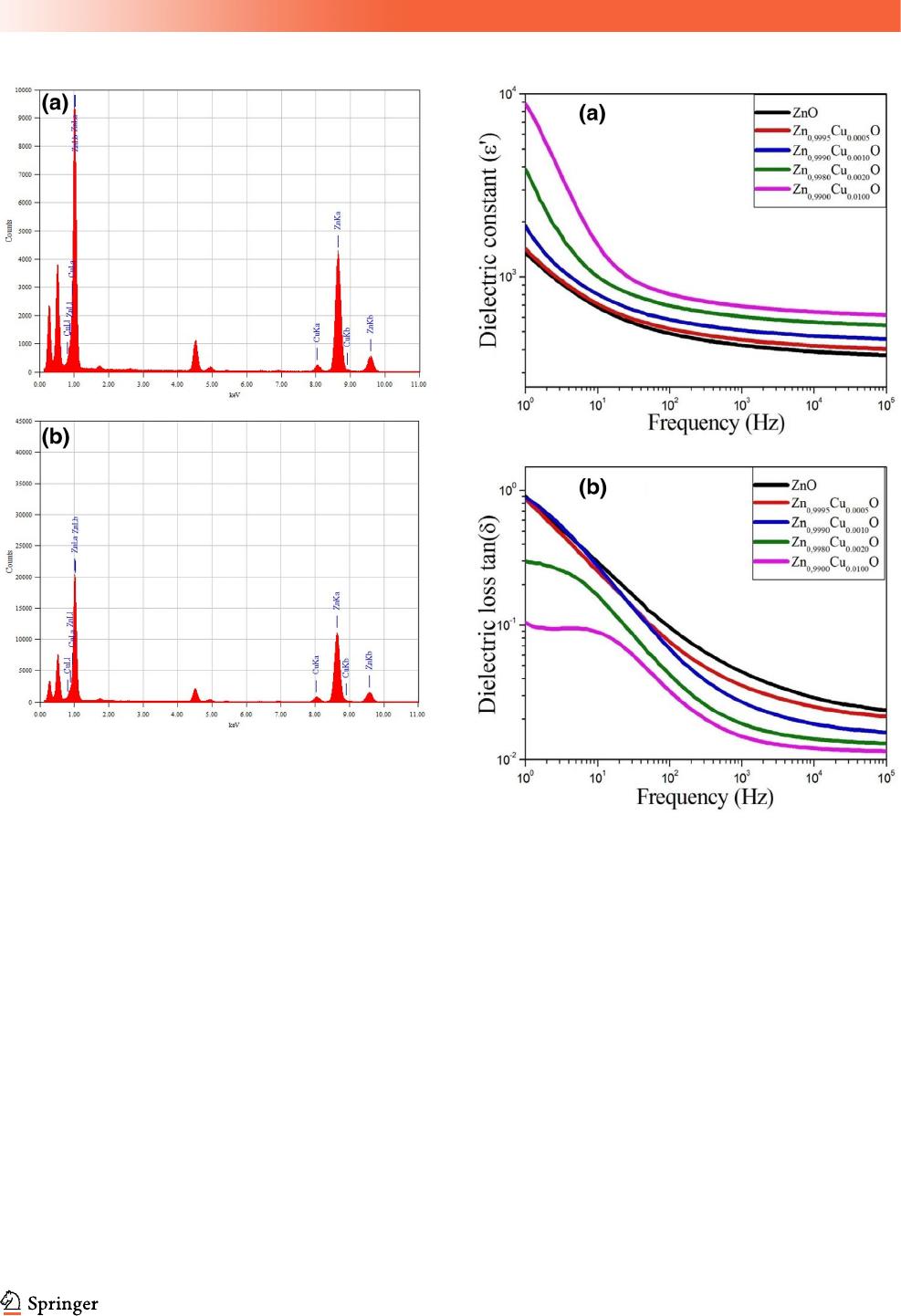

To further verify the successful preparation of

desired nanoparticles, EDAX analyses were carried

out as shown in Fig. 4. The analyses indicate that the

Zn

1-x

Cu

x

O nanoparticles are of high purity since

only Cu, Zn and O elements were detected. The

existence of Ti (at 4–5 eV) is due to titanium grid

utilized for the TEM/EDAX examination.

3.2 Dielectric and impedance studies

of Zn

12x

Cu

x

O nanoparticles

3.2.1 Dielectric properties

The study of the dielectric properties of materials is

an essential parameter for integrating these materials

into microelectronic application devices. The dielec-

tric properties of theZn

1-x

Cu

x

O (x = 0.0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2

and 1%) nanoparticles were measured as a function

of frequency at room temperature. The variation of

dielectric constant (e

0

) for various samples is shown

in Fig. 5a. For all compositions, it is found that the

dielectric constant decreases rapidly in the low fre-

quency region, and then became more and less con-

stant at higher frequencies representing the dielectric

dispersion. The observed decrease in e

0

at the low

frequency region is a common and known feature

behavior for amorphous, polycrystalline and oxides

materials [40, 41]. This dispersion can be attributed to

the interfacial polarization (film/electrode and/or in

grain boundary interfaces) in agreement with Koop’s

phenomenological theory [42]. Starting from 100 Hz,

the decrease of the dielectric constant with the fre-

quency becomes weak and shows good stability at

high frequency. It is clear that the dielectric constant

is depended on the Cu concentration throughout the

frequency range. It increases significantly with

increasing Cu content. For example, the obtained

Fig. 1 a X-ray diffraction patterns of Zn

1-x

Cu

x

O nanoparticles,

b variation of lattice parameters as a function of Cu content

J Mater Sci: Mater Electron

permittivities at 1 kHz are equal to 422, 452, 510, 606

and 693 for x = 0.0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2 and 1%, respectively.

It can be concluded that the increase in the Cu con-

tent within ZnO nanoparticles (even with low Cu

quantity) increases the permittivity and improves its

stability at high frequencies. The observed results are

very encouraging for microwave applications.

The frequency dependence of the dielectric loss

tangent (tand = e

00

/e

0

) for all samples at room tem-

peratures is shown in Fig. 6b. The curves of tand vs.

frequency for Zn

1-x

Cu

x

O (x = 0.0, 0.05, and 0.1%)

show the same behavior. In fact, tand decreases

rapidly with increasing frequency, showing a dis-

persion phenomenon at low frequencies. For

x = 0.2% and x = 1%, a relaxation peak was appeared

at low frequencies. The dielectric loss (tand) is also

influenced by the concentration of Cu dopant. At

1 kHz, tand values obtained are around 0.045, 0.035,

0.026, 0.018 and 0.0014 for x = 0.0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2 and

1%, respectively. It is important to note that the

increase in Cu content within ZnO nanoparticles

leads to increase the permittivity and decrease the

dielectric loss. This implies that Cu-doped

ZnO nanoparticles are good candidates for various

microelectronic applications such as sensors, memory

devices, actuators, MOS capacitors and semiconduc-

tor microwave devices.

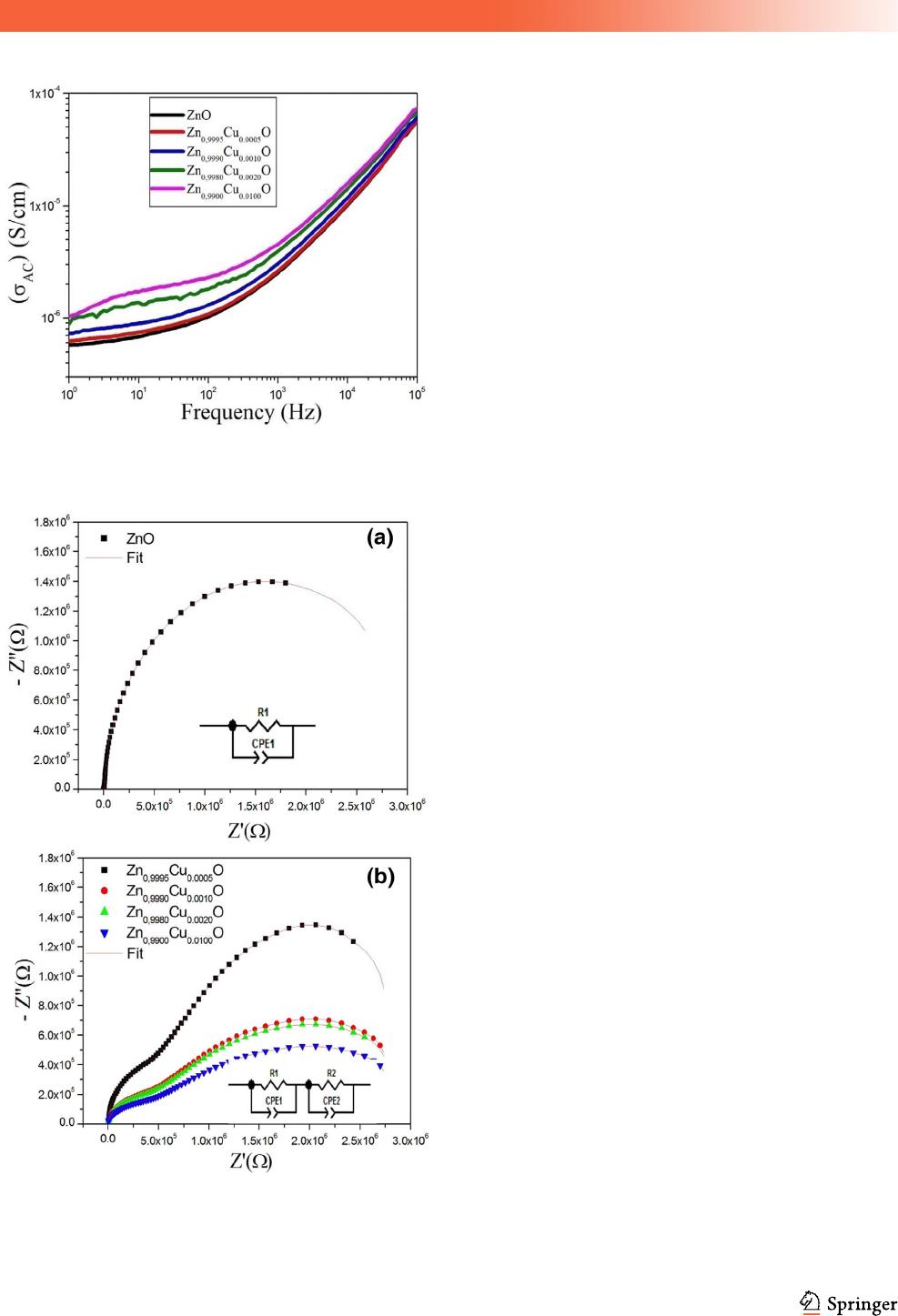

3.2.2 AC conductivity investigation

Using the data of e

0

and tan(d), the ac electrical con-

ductivity (r

ac

) of the Zn

1-x

Cu

x

O nanoparticles can be

calculated from the empirical formula: r

ac

= xe

0

e

0

tan(d), where x is the angular frequency and e

0

is the

vacuum permittivity [43]. Figure 6 shows the fre-

quency dependence of ac conductivity (r

ac

) at room

temperature for pure and Cu-doped ZnO nanoparti-

cles. One can observe two regions; the conductivity is

almost frequency independent in the low frequency

region, while it is strongly dependent on frequency at

the high frequency region (starting from 100 Hz).

Table 1 Molar Cu concentration, lattice parameters, cell volume, BET-specific surface area, crystallites size and bandgap for Zn

1-x

Cu

x

O

nanoparticles

Cu content in the synthesis mixture 0.00% 0.05% 0.10% 0.20% 1.00%

Cu content in Zn

1-x

Cu

x

O 0.00% 0.02% 0.05% 0.07% 0.37%

a(A

˚

) 3.2509 (3) 3.2502 (3) 3.2494 (2) 3.2485 (8) 3.2480 (2)

c(A

˚

) 5.2079 (4) 5.2071 (2) 5.2070 (4) 5.2068 (5) 5.2045 (2)

Cell volume (A

˚

3

) 48.5876 (2) 48.5562(1) 48.5248 (3) 48.4801 (1) 48.4577 (2)

BET surface area (m

2

/g) 21 ± 320± 220± 219± 318± 2

Crystallites size D

XRD

(± 1 nm)

18.9 17.5 15.3 12.7 9.8

Bandgap (eV) 3.16 3.08 2.94 2.88 2.57

Fig. 2 a UV–visible diffuse reflectance spectra, and b Tauc plots

for pure and Cu-doped ZnO nanoparticles

J Mater Sci: Mater Electron

Therefore, the ac conductivity can be described by the

Jonscher’s power law: r

ac

= r

dc

? A x

n

where r

dc

is

the dc bulk conductivity, A is a pre-exponential

constant, and n is the power law exponent [44]. One

can observe that the conductivity of the Zn

1-x

Cu

x

O

nanoparticles increases with the increase in Cu con-

tent. This increase is clearer in the low frequencies

region.

3.2.3 Complex impedance analysis

For polycrystalline structure, it is always better to

separate the effects of the dissociation between the

bulk and the interface. Accordingly, we investigated

the complex impedance spectra of Zn

1-x

Cu

x

O

nanoparticles. The complex impedance (Z

*

) can be

written in the following form: Z

*

= Z

0

- jZ

00

. The real

and imaginary parts (Z

0

and Z

00

) of the complex

impedance can be also expressed as a function of e

0

and e

00

as shown in the following expressions:

Z

0

¼

e

00

xC

0

e

02

þ e

002

ðÞ

and

Z

00

¼

e

0

xC

0

e

02

þ e

002

ðÞ

where e

0

and e

00

are the real and imaginary parts of the

complex permittivity (e

*

), x =2pf is the angular fre-

quency, C

0

= e

0

A/t is the geometrical capacitance, e

0

is the permittivity of free space, A is the area of

electrode surface and t is the thickness. Figure 7a

shows the Nyquist plot (Z

00

versus Z

0

) at room tem-

perature for Zn

1-x

Cu

x

O nanoparticles (x = 0.0%, 0.05,

0.1, 0.2 and 1%). The pure ZnO nanoparticles showed

only one semi-circle, while the Cu-doped ZnO

nanoparticles showed two semi-circles. The semi-

circle observed at the lower frequency region is

attributed to the contribution of grain boundary and

the interfacial effect specified by the interface

between the Cu and the ZnO nanoparticles

Fig. 3 TEM micrographs of Zn

1-x

Cu

x

O; a x = 0.00%, b x = 0.05%, c x = 0.1%, d x = 0.2% and e x = 1%, and f HRTEM micrograph

of ZnO nanoparticles

J Mater Sci: Mater Electron

(interfacial properties), while the semi-circle occurred

at the higher frequency region is associated to the

grain effect (bulk properties). By using Z-View 2

software, the experimental impedance measurements

were best fitted with the equivalent circuit based on

the brick-layer model as shown in Fig. 7a and b. For

pure ZnO nanoparticles, the equivalent circuit is

composed of a one-cell constituted by a parallel

combination of Rp and CPE. The equivalent circuit

obtained for the doped Zn

1-x

Cu

x

O nanoparticles is

formed by two cells connected in series each con-

sisting of a parallel combination of Rp and CPE

representing grain and grain boundaries effects,

respectively.

4 Conclusion

In this study, we have prepared Zn

1-x

Cu

x

O

nanoparticles (where x = 0.00, 0.05, 0.10, 0.20 and

1.00%) using a one-pot polyol process, without add-

ing any other reagent, template or complex metal

ligand. XRD analysis showed the successful forma-

tion of the Zn

1-x

Cu

x

O nanoparticles with hexagonal

wurtzite structure. TEM and EDAX analyses showed

high purity of Cu-doped ZnO nanoparticles with

spherical shape and a size ranging between 9 and

20 nm. HRTEM image showed well-defined ZnO

crystal planes. The investigation of electrical and

dielectric properties indicated that the increase in the

Fig. 4 EDAX spectra of Zn

1-x

Cu

x

O nanoparticles; a x = 0.05%

and b x = 0.1%

Fig. 5 Frequency dependence of dielectric constant (e

0

) and

tangent loss (tan d) forZn

1-x

Cu

x

O nanoparticles measured at room

temperature (25 °C)

J Mater Sci: Mater Electron

Cu content improves greatly the dielectric properties

of Zn

1-x

Cu

x

O nanoparticles. It is found that the

permittivity increased and the dielectric loss

decreased with Cu doping. The obtained results are

very encouraging to use the Zn

1-x

Cu

x

O nanoparticles

in semiconductor microwave devices.

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by the Deanship of Scientific

Research (DSR), King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah,

under grant. No. (D-625-130-1441). The authors,

therefore, gratefully acknowledge DSR technical and

financial supports.

References

1. L. Santos, C.M. Silveira, E. Elangovan, J.P. Neto, D. Nunes,

L. Pereira, R. Martins, J. Viegas, J.J. Moura, S. Todorovic,

M.G. Almeida, Synthesis of WO3 nanoparticles for biosens-

ing applications. Sens. Actuators B 223, 186–194 (2016)

2. X. Wang, H. Huang, B. Liang, Z. Liu, D. Chen, G. Shen, ZnS

nanostructures: synthesis, properties, and applications. Crit.

Rev. Solid State Mater. Sci. 38(1), 57–90 (2013)

3. Y. Al-Douri, Optical properties of GaN nanostructures for

optoelectronic applications. Procedia Eng. 53, 400–404

(2013)

4. P.K. Mishra, H. Mishra, A. Ekielski, S. Talegaonkar, B.

Vaidya, Zinc oxide nanoparticles: a promising nanomaterial

for biomedical applications. Drug Discov. Today 22,

1825–1834 (2017)

5. E. Manikandan, V. Murugan, G. Kavitha, P. Babu, M. Maaza,

Nanoflower rod wire-like structures of dual metal (Al and Cr)

doped ZnO thin films: structural, optical and electronic

properties. Mater. Lett. 131, 225–228 (2014)

6. R. Tayebee, A.H. Nasr, S. Rabiee, E. Adibi, Zinc oxide as a

useful and recyclable catalyst for the one-pot synthesis of

2,4,6-trisubstituted-1,3,5-trioxanes under solvent-free condi-

tions. Eng. Chem. Res. 52, 9538–9543 (2013)

7. A.H. Shah, M.B. Ahamed, E. Manikandan, R. Chandramo-

han, M. Iydroose, Magnetic, optical and structural studies on

Ag doped ZnO nanoparticles. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron.

24, 2302–2308 (2013)

8. M. Kaushik, R. Niranjan, R. Thangam, B. Madhan, V.

Pandiyarasan, C. Ramachandran, D.H. Oh, G.D. Venkata-

subbu, Investigations on the antimicrobial activity and wound

healing potential of ZnO nanoparticles. Appl. Surf. Sci. 479,

1169–1177 (2019)

Fig. 6 Variation of ac conductivity (r

ac

) with frequency for

Zn

1-x

Cu

x

O nanoparticles

Fig. 7 Typical Nyquist Plot for Zn

1-x

Cu

x

O nanoparticles at room

temperature and the corresponding equivalent circuit

J Mater Sci: Mater Electron

9. K. Lokesh, G. Kavitha, E. Manikandan, G.K. Mani, K.

Kaviyarasu, J.B. Rayappan, R. Ladchumananandasivam, J.S.

Aanand, M. Jayachandran, M. Maaza, Effective ammonia

detection using n-ZnO/p-NiO heterostructured nanofibers.

IEEE Sens. J. 16(8), 2477–2483 (2016)

10. S. Goel, B. Kumar, A review on piezo-/ferro-electric prop-

erties of morphologically diverse ZnO nanostructures. J. Al-

loys Compds. 816, 152491 (2020)

11. H. Agarwal, S.V. Kumar, S. Rajeshkumar, A review on green

synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles—an eco-friendly

approach. Resource Effic. Technol. 3(4), 406–413 (2017)

12. R. Raji, K.G. Gopchandran, ZnO nanostructures with tunable

visible luminescence: effects of kinetics of chemical reduction

and annealing. J. Sci. Adv. Mater. Dev. 2, 51–58 (2017)

13. B.D. Ngom, T. Mpahane, E. Manikandan, M. Maaz, ZnO

nano-discs by lyophilization process: size effects on their

intrinsic luminescence. J. Alloy Compd. 656, 758–763 (2016)

14. S.P. Chang, K.J. Chen, Zinc oxide nanoparticle photodetector.

J. Nanomater. 602398 (2012)

15. A. Muthukumar, D. Arivuoli, E. Manikandan, M. Jayachan-

dran, Enhanced violet photoemission of nanocrystalline flu-

orine doped zinc oxide (FZO) thin films. Opt. Mater. 47,

88–94 (2015)

16. S. Bhatia, N. Verma, R.K. Bedi, Ethanol gas sensor based

upon ZnO nanoparticles prepared by different techniques.

Results Phys. 7, 801–806 (2017)

17. G. Kavitha, K. Thanigai Arul, P. Babu, Enhanced acetone gas

sensing behavior of n-ZnO/p-NiO nanostructures. J. Mater.

Sci.: Mater. Electron. 2(8), 6666–6671 (2018)

18. L. Chen, Z. Yu-Ming, Z. Yi-Men, L. Hong-Liang, Interfacial

characteristics of Al/Al

2

O

3

/ZnO/n-GaAs MOS capacitor.

Chin. Phys. B 22(7), 076701 (2013)

19. M. Laurenti, N. Garinoa, S. Porro, M. Fontana, C. Gerbaldi,

Zinc oxide nanostructures by chemical vapour deposition as

anodes for Li-ion batteries. J. Alloy Compd. 640, 321–326

(2015)

20. K.K. Kim, D. Kim, S.K. Kim, S.M. Park, J.K. Song, For-

mation of ZnO nanoparticles by laser ablation in neat water.

Chem. Phys. Lett. 511(1–3), 116–120 (2011)

21. N.T. Rochman, A.P. Riski, Fabrication and characterization of

Zinc Oxide (ZnO) nanoparticle by sol-gel method. JPhCS.

853(1), 012041 (2017)

22. P. Veluswamy, S. Suhasini, F. Khan, A. Ghosh, M. Abhijit, Y.

Hayakawa, H. Ikeda, Incorporation of ZnO and their com-

posite nanostructured material into a cotton fabric platform

for wearable device applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 157,

1801–1808 (2016)

23. P. Veluswamy, S. Suhasini, J. Archana, M. Navaneethan, A.

Majumdar, Y. Hayakawa, H. Ikeda, Fabrication of

hierarchical ZnO nanostructures on cotton fabric for wearable

device applications. Appl. Surf. Sci. 418, 352–361 (2017)

24. O

¨

.A. Yıldı r ım, C. Durucan, Synthesis of zinc oxide

nanoparticles elaborated by micro-emulsion method. J. Alloy.

Compd. 506 , 944–949 (2010)

25. D.B. Bharti, A.V. Bharati, Synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles

using a hydrothermal method and a study its optical activity.

Luminescence 32, 317–320 (2017)

26. B.W. Chieng, Y.Y. Loo, Synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles by

modified polyol method. Mater. Lett. 73, 78–82 (2012)

27. F. Fie´vet, S. Ammar-Merah, R. Brayner, F. Chau, M. Giraud,

F. Mammeri, J. Peron, J.-Y. Piquemal, L. Sicard, G. Viau, The

polyol process: a unique method for easy access to metal

nanoparticles with tailored sizes, shapes and compositions.

Chem. Soc. Rev. 47(47), 5187–5233 (2018)

28. S. Sharma, K. Nanda, R.S. Kundu, R. Punia, N. Kishore,

Structural properties, conductivity, dielectric studies and

modulus formulation of Ni modified ZnO nanoparticles.

J. Atom. Mol. Condens. Nano Phys. 2, 15–31 (2015)

29. C. Thenmozhi, V. Manivannan, E. Kumar, S. Veera, R.

Murugan, Structural and frequency dependent dielectric

properties of ZnO nanoparticles and PANI/ ZnO nanocom-

posites by microwave—assisted solution method. Int. J. Adv.

Res. 4, 572–578 (2016)

30. I. Ahmad, M.E. Mazhar, M.N. Usmani, K. Khan, S. Ahmad,

J. Ahmad, Impact of silver dopant on electrical and dielectric

properties of ZnO nanoparticles. Mater. Res. Express 6,

035014 (2019)

31. C. Belkhaoui, R. Lefi, N. Mzabi, H. Smaoui, Synthesis,

optical and electrical properties of Mn doped ZnO nanopar-

ticles. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 29, 7020–7031 (2018)

32. R. Zamiri, B. Singh, M.S. Belsley, J.M. Ferreira, Structural

and dielectric properties of Al-doped ZnO nanostructures.

Ceram. Int. 40, 6031–6036 (2014)

33. A. Franco Jr., H.V.S. Pessoni, Enhanced dielectric constant of

Co-doped ZnO nanoparticulate powders. Phys. B 476, 12–18

(2015)

34. H.M. Rietveld, Line profiles of neutron powder-diffraction

peaks for structure refinement. J. Acta Cryst. 22, 151–152

(1967)

35. C.J. Rodriguez, A Program for Rietveld Refinement and

Pattern Matching Analysis,’’ Abstract of the Satellite Meeting

on Powder Diffraction of the XV Congress of the IUCr,

Collected Abstract of Powder Diffraction Meeting. Toulouse,

France, (1990) 127.

36. R.D. Shannon, Revised effective ionic radii and systematic

studies of interatomic distances in halides and chalcogenides.

Acta Cryst. A 32, 751–767 (1976)

J Mater Sci: Mater Electron

37. M. Fu, Y. Li, S. Wu, P. Lu, J. Liu, F. Dong, Sol-gel prepa-

ration and enhanced photocatalytic performance of Cu-doped

ZnO nanoparticles. Appl. Surf. Sci. 258, 1587–1591 (2011)

38. M. Moffitt, A. Eisenberg, Size control of nanoparticles in

semiconductor-polymer composites. 1. Control via multiplet

aggregation numbers in styrene-based random ionomers.

J. Chem. Mater. 7, 1178–1184 (1995)

39. C. Wu, L. Shen, H. Yu, Y.C. Zhang, Q. Huang, Solvothermal

synthesis of Cu-doped ZnO nanowires with visible light-dri-

ven photocatalytic activity. J. Mater Lett. 74, 236–238 (2012)

40. A. Selmi, M. Mascot, F. Jomni, J.-C. Carru, Investigation of

interfacial dead layers parameters in Au/Ba0.85Sr0.15TiO3/Pt

capacitor devices. J. Alloys Compds. 826, 154048 (2020)

41. K. Jeyasubramaniana, R.V. William, P. Thiruramanathan,

G.S. Hikku, M. Vimal Kumar, B. Ashima, P. Veluswamy, H.

Ikeda, Dielectric and magnetic properties of nanoporous

nickel doped zinc oxide for spintronic applications. J. Magn.

Magn. Mater. 485, 27–35 (2019)

42. Y. Slimani, A. Selmi, E. Hannachi, M.A. Almessiere, A.

Baykal, I. Ercan, Impact of ZnO addition on structural,

morphological, optical, dielectric and electrical performances

of BaTiO3 ceramics. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 30,

9520–9530 (2019)

43. A. Selmi, M. Mascot, F. Jomni, J.-C. Carru, High tunability in

lead-free Ba0.85Sr0.15TiO3thick films for microwave tun-

able applications. Ceram. Int. B 45, 22445–23856 (2019)

44. A. Selmi, O. Khaldi, M. Mascot, F. Jomni, J.-C. Carru,

Dielectric relaxations in Ba

0.85

Sr

0.15

TiO

3

thin films deposited

on Pt/Ti/SiO

2

/Si substrates by sol–gel method. J. Mater. Sci.:

Mater. Electron. 27, 11299–11307 (2016)

Publisher’s Note Springer Nature remains neutral with

regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and

institutional affiliations.

J Mater Sci: Mater Electron