Vol.:(0123456789)

1 3

Breast Cancer

https://doi.org/10.1007/s12282-020-01129-5

CASE REPORT

Kounis syndrome afterpatent blue dye injection forsentinel lymph

node biopsy

MaximosFrountzas

1

· PanagiotisKarathanasis

1

· GavriellaZoiVrakopoulou

1

· CharalamposTheodoropoulos

1

·

ConstantinosG.Zografos

2

· DimitriosSchizas

2

· GeorgeC.Zografos

1

· NikolaosV.Michalopoulos

1,3

Received: 11 May 2020 / Accepted: 22 June 2020

© The Japanese Breast Cancer Society 2020

Abstract

Background Kounis syndrome (KS) has been described as an acute coronary syndrome (ACS) associated with an anaphy-

lactic reaction. Several triggers have been identified and the diagnostic and treatment process can be challenging.

Case A 58-year-old, female patient diagnosed with breast cancer and no history of allergies had subcutaneous injection

of patent blue V dye for sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB). Intraoperatively, she developed anaphylactic shock and was

transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU). A few hours later, electrocardiographic alterations and elevation of blood troponin

were observed. Emergency coronary angiography revealed no occlusive lesions in coronary vessels. Further investigation in

the allergy department set the diagnosis of KS.

Conclusion There are just ten cases of perioperative KS in the literature so far and here we present the first one triggered by

patent blue V dye for sentinel node biopsy.

Keywords Kounis syndrome· Patent blue· Sentinel node biopsy

Introduction

Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) has been considered as

the gold standard method for axillary staging in early breast

cancer. Surgeons traditionally utilize intra-parenchymal

injection of blue dye, either alone or in combination with

a radiotracer [1]. Patent blue violet (V) has been the most

commonly used blue dye outside the USA, despite its minor

allergic reaction risk, which is below 1% [2]. Patent blue V

allergic reactions could vary from simple cutaneous mani-

festations to cardiac arrest [3].

Kounis Syndrome (KS) is an extremely rare anaphylactic

reaction to various allergens, which is associated with acute

coronary syndrome [4]. KS leads to hypovolemic shock of

cardiogenic etiology, that actually should be treated as an

anaphylactic one. Herein we present the first case in the

literature concerning KS after patent blue V injection for

SLNB in early-stage breast cancer.

Case report

A 58-year-old Caucasian woman with an invasive ductal car-

cinoma in the upper outer quadrant of the right breast was

scheduled for breast conserving operation and axillary sen-

tinel lymph node biopsy. Her past medical history included

only a mild dilatation of the thoracic aorta (4.2cm). No

allergies were reported. The preoperative echocardiogram

revealed no abnormalities with a left ventricular ejection

fraction of 55–60%. During the operation, 2ml of patent

blue V was administered subcutaneously in the periareolar

area of the right breast.

Approximately 15min after patent blue V dye injection,

the patient progressively developed tachycardia (110bpm)

followed by hypotension (blood pressure: 60/30mmHg).

* Maximos Frountzas

1

1st Department ofPropaedeutic Surgery, Medical School,

“Hippocratio” General Hospital, University ofAthens, 114

Vas. Sophias Av, 11527Athens, Greece

2

1st Department ofSurgery, Medical School, University

ofAthens, “Laiko” General Hospital, 17 Agiou Thoma St,

11527Athens, Greece

3

4th Dept. ofSurgery, Medical School, “Attikon” University

Hospital, University ofAthens, 1 Rimini St, 12462Chaidari,

Greece

Breast Cancer

1 3

Pulse oximetry decreased from 100 to 95%. The patient

developed a rash initially in the face, which gradually

expanded in the whole body, and a systemic allergic reac-

tion was diagnosed. The patient immediately received

bolus doses of corticosteroids and dimetindene. In addi-

tion, fluid resuscitation with 3L of crystalloids and doses

of norepinephrine were administered to maintain blood

pressure in normal values. High-sensitivity (HS) troponin-

I levels were normal (2.23mg/dl).

The patient was transferred to the intensive care unit

(ICU) for monitoring. 6h later, electrocardiogram abnor-

malities (depression of ST segment in leads II and III)

were observed (Fig.1). New blood samples for HS tro-

ponin-I were abnormal (2360mg/dl). She underwent a

new echocardiogram, which demonstrated a decrease of

ejection fraction (40%) and a hypokinetic left cardiac ven-

tricle. The patient was treated with dual antiplatelet ther-

apy (clopidogrel 300mg and acetylsalicylic acid 100mg)

and underwent emergent coronary angiography, which

revealed no occlusive lesions in the coronary arteries, but

confirmed the low ejection fraction (40%). The follow-

ing 24h her condition gradually improved and she was

extubated the next day, being haemodynamically stable

and without need of vasopressor support. After Intensive

Care Unit discharge, the levels of HS troponin-I gradually

decreased until they became normal, and she was finally

discharged from hospital on the sixth postoperative day.

A month later, the patient was reviewed at the Allergy

and Immunology Department, where allergy to patent blue

V was confirmed.

Discussion

Kounis syndrome (KS), or “allergic angina syndrome”,

is defined as the co-incidental occurrence of an acute

coronary syndrome (ACS) associated with mast cell and

platelet activation in the setting of an allergic or anaphy-

lactic insult [5]. Its annual incidence is 4 to 10 cases per

100,000 inhabitants and its mortality rate is 0.0001% [6,

7]. Although KS could be presented in any age group,

68% of patients affected are between 40 and 70years. Risk

factors of KS include history of allergy, hypertension,

smoking, diabetes and hyperlipidemia. The most common

triggers of KS are antibiotics (27.4%) followed by insect

bites (23.4%), even though more triggers are still under

investigation [8].

Three main types of KS have been described so far:

•

Type I (without coronary disease, 75%): patients with-

out previous history of coronary disease, who present

anaphylactic reaction that causes coronary vessels

spasm. Electrocardiographic changes cardiac enzymes

elevation could be present. Endothelial dysfunction

and/or microvascular angina have been proposed as

probable pathophysiological mechanisms of this type

of KS [9].

•

Type II (with coronary disease, 20%): patients with pre-

existing atheromatous disease, either symptomatic or

unknown, in which the hypersensitivity reaction causes

plaque erosion or rupture, leading to acute myocardial

infarction [10].

•

Type III (with stents, 5%): patients with previous cor-

onary artery disease and drug-eluting stents that get

thrombosed due to hypersensitivity vasculitis [11].

KS is characterized by the interaction between mast cells,

macrophages and T-lymphocytes, which activates an inflam-

mation cascade that is mediated by several molecules and

leads to coronary artery spasm and/or atheromatous plaque

erosion or rupture during an allergic reaction [12, 13]. Mast

cells are located in the areas of coronary plaque erosion or

rupture, whereas they act on the smooth muscle of the coro-

nary arteries [14]. The inflammation cascade is triggered

by antigen–antibody reaction on the surface of the mast and

basophil cells, or activation of the complement system (C3a,

C5a), which explains the rapid—less than 60min—manifes-

tation of KS after trigger exposure [15]. In addition, there is

a threshold beyond which the inflammation cascade is acti-

vated, that depends on the body site, where the antigen–anti-

body reaction occurs, the area of exposure, the mediators

release and the severity of the allergic reaction [16].

Therefore, it is understandable why KS is exacerbated

very quickly with high severity perioperatively, where the

Fig. 1 Electrocardiogram showing alterations (ST segment depres-

sion in leads II and III) developed during Intensive Care Unit stay

Breast Cancer

1 3

potential triggers are administrated in the blood circula-

tion, either during general anesthesia induction or during

an operation. Only ten cases of perioperative KS have been

reported in the literature so far (Table1). In six of them,

KS was presented during general anesthesia induction or

immediately after that, but before skin incision. The rest

four cases were reported intraoperatively after skin inci-

sion by surgeons. Several triggers have been reported to

cause perioperative KS such as rocuronium, cefazoline,

gelofusine, midazolam, bupivacaine, latex and succi-

nylated gelatin. In 80% of the patients that experienced a

perioperative KS, there was no history of allergy or previ-

ous coronary disease (Type I).

Perioperative KS has presented as hypovolemic shock—

hypotension and tachycardia—during anesthesia induction

or within 60min after it. However, only in four out of ten

reported cases electrocardiographic alterations and rash were

initially manifested. In four more cases ACS was identified

by electrocardiographic alterations without clinical signs of

anaphylactic reaction. Finally, in two cases allergic reac-

tion was the first manifestation with a rash, but no initially

clinical signs of a coronary syndrome. Simultaneous clinical

signs of ACS and allergic reaction impose a serious diagnos-

tic problem and one out of ten patients died due to periop-

erative KS. All cases were managed according to ACS and

anaphylactic reaction therapeutic protocols.

KS in the operating room may prove serious and usually

presents as a hypovolemic shock. The key for successful

management of such a shock in an intubated patient is recog-

nizing the cause. This may prove to be challenging, as only

40% of patients develop a combination of ACS and allergic

clinical signs. Similar to what happened in our case, 20% of

patients with perioperative KS initially manifest an anaphy-

lactic reaction without ACS. Therefore, they are generally

treated for anaphylactic shock, as the pathophysiologic basis

of coronary occlusion in KS is based on hypersensitivity

reactions, that are resolved by corticosteroids and antihis-

tamines [17]. The main problem, however, exists in 40% of

patients with perioperative KS, that present ACS without

an initial anaphylactic reaction. These patients are treated

according to an ACS therapeutic protocol that is usually

not effective, because it actually does not deal with the real

cause of coronary occlusion [18]. The key for such patients

is raised suspicion by anesthesiologists and surgeons, with

continuous assessment of their whole body for clinical signs

of allergic reaction.

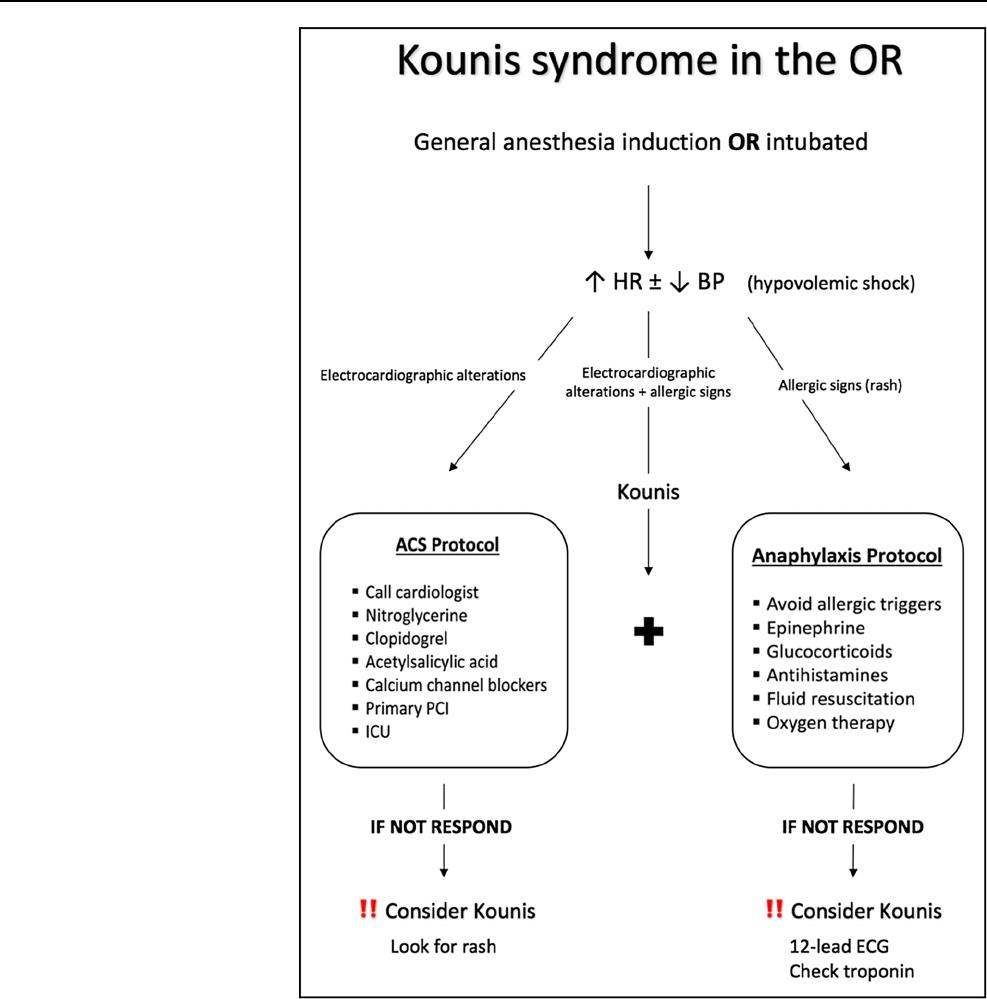

A possible algorithm for treating perioperative KS is shown

in Fig.2. When its anaphylactic component is present, all aller-

gic triggers should be removed, epinephrine, glucocorticoids

and antihistamines should be administered in combination to

high flow oxygen and fluid resuscitation [19]. When its coro-

nary syndrome component is present, a cardiology review and

administration of nitroglycerine, double antiplatelet medica-

tion (clopidogrel and acetylsalicylic acid) and calcium chan-

nel blockers (diltiazem, verapamil) is advised [20]. Primary

percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and ICU monitoring

are usually indicated Fig. (2).

In our case, patent blue V dye has triggered KS. Several

allergic reactions against patent blue V have been reported

in the literature, the incidence of which varies between 0.06

and 2.7%, with a mean value of 0.71%. Patent blue V allergic

reactions could vary from simple cutaneous manifestations to

cardiac arrest. Fortunately, the reported risk of severe allergic

reactions, that required vasopressors administration or surgery

interruption, remained extremely low and barely reached 0.1%

[21]. In addition, methylene blue has been proposed as a poten-

tial alternative to patent blue V, due to its comparable efficacy

in SLN identification, its lower cost and its decreased allergic

stimulation (below 0.5%). However, the possibility for cross

reactivity between these two dyes still exists [22]. Moreover,

super paramagnetic iron oxide (SPIO) nanoparticles and indo-

cyanine green fluorescence (ICG) have demonstrated adequate

efficiency in SLN mapping in combination to a radio-isotope,

but their safety has still to be proved [23, 24]. Finally, the uti-

lization of a radio-isotope alone without a blue dye is another

proposed option that showed comparable SLN identification

rates, but required advanced surgical experience [25]. Nev-

ertheless, patent blue V has never been reported as a trigger

for KS.

Conclusion

KS is a combination of ACS and anaphylactic reaction that

rarely happens in the operating room. Diagnosis demands

raised suspicion by anesthesiologists and surgeons, when they

are facing an intraoperative shock without a clear cause, which

does not respond to usual therapeutic protocols. Multiple trig-

gers have been reported up to date and our case identified pat-

ent blue V for sentinel lymph node biopsy as a new one.

Breast Cancer

1 3

Table1 Kounis syndrome in the operating room

Date; Study Surgery Cause Type LVEF ECG Treatment Outcome Allergies Onset ACS Onset

anaphy-

laxis

Before skin incision

2013; Sanchez Rotator cuff

arthroscopy

Rocuro-

nium ± Cefa-

zoline

I N/A ST elevation in front

and bottom of

heart

Nitroglycerine, clopidogrel,

acetylsalicylic acid

Methylprednisolone, dex-

chlorpheniramine, raniti-

dine, ephedrine

Primary PCI

Discharged No Yes Yes

2013; Shah Urologic Gelofusine II Normal ST elevations in 3

leads, pulseless

electrical activ-

ity and p-wave

asystole

Metaraminol, epinephrine,

atropine, norepinephrine

CTCA

Discharged Penicillin

Anti-tetanus

serum

Yes Yes

2015; Ates TURP Midazolam I Normal ST depression on

anterior deriva-

tions

Acetylsalicylic acid, LMWH,

atorvastatin, ranitidine

Antihistamines and corticos-

teroids

Primary PCI

Discharged No Yes No

2016; Lerner Lipoma (local

anesthesia)

Bupiv-

acaine ± lido-

caine

I 70% ST elevation in

inferior leads, ven-

tricular fibrillation

and cardiac arrest

Defibrillations, epinephrine,

amiodarone

Primary PCI

Discharged Insect stings

and oxytetra-

cycline

Yes Yes

2017; Sakamoto LAP ileocecal

excision

Rocuronium I N/A ST elevation Adrenaline, noradrenaline,

atropine, amiodarone

Steroids and antihistamines

Primary PCI

Discharged N/A Yes Yes

2018; Vasquez Foot Fracture Fentanyl ± bupiv-

acaine

I Diastolic

dysfunc-

tion

Signs of ischemia Ephedrine, dexamethasone,

salbutamol, epinephrine

Aspirin, clopidogrel, atorv-

astatin

Primary PCI

Cardio-respiratory

arrest

N/A No Yes

After skin incision

2012; Takenaka Varicose vein

stripping

Latex I Normal ST elevation Ephedrine, phenylephrine and

noradrenaline, adrenaline

Nitroglycerin, noradrenaline,

diltiazem

Discharged No Yes No

Breast Cancer

1 3

N/A non-available, LVEF left ventricular ejection fraction, ECG electrocardiogram, LAP laparoscopic, ACS acute coronary syndrome, TURP transurethral prostatectomy, TURB transurethral

resection of bladder tumor, CTCA computerized tomography coronary angiography, LMWH low molecular weight heparin, PCI percutaneous coronary intervention

Table1 (continued)

Date; Study Surgery Cause Type LVEF ECG Treatment Outcome Allergies Onset ACS Onset

anaphy-

laxis

2013; Marcoux Hernia repair Latex II 57% Third-degree

AV-block and ST-

elevations

Ephedrine, glycopyrrolate,

epinephrine, salbutamol,

norepinephrine

Clopidogrel and acetylsali-

cylic acid

Primary PCI

Coronary re-

stenosis after

4months

No Yes No

2017; Tornero Spinal surgery Succinylated

gelatin

I Lateral wall

motion

abnor-

malities

ST depression in the

left-sided leads

Ephedrine, epinephrine,

hydrocortisone, sugamma-

dex, dexamethasone

Heparin, amiodarone

Primary PCI

Discharged No No Yes

2019; Sato TURB and

LAP nephro-

ureterectomy

Cefazolin I N/A ST in lead II of the

ECG decreased

Nitroglycerin and nicorandil

Corticosteroids and chlorphe-

niramine

CTCA

Discharged No Yes No

2020; Our case Breast surgery Patent blue V I 40% ST depressions in

leads II and III

Dimetindene, corticosteroids,

norepinephrine

Clopidogrel, acetylsalicylic

acid

Primary PCI

Discharged No No Yes

Breast Cancer

1 3

Funding None to disclose for all authors.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest The authors report no conflict of interest.

Informal consent For this type of study formal consent is not required.

References

1. Bézu C, etal. Anaphylactic response to blue dye during sentinel

lymph node biopsy. Surg Oncol. 2011;20(1):e55–e59.

2. Barthelmes L., etal. on behalf of the NEW START and ALMA-

NACH study groups. Eur J Surg oncol. 2009.

3. Montgomery LL, etal. Isosulfan blue dye reactions during

sentinel lymph node mapping for breast cancer. Anesth Analg.

2002;95(2):385–8.

4. Kounis N, Zavras G. Histamine-induced coronary artery

spasm: the concept of allergic angina. Br J Clin Pract.

1991;45(2):121–8.

5. Kounis NG. Kounis syndrome: an update on epidemiology,

pathogenesis, diagnosis and therapeutic management. Clin

Chem Lab Med (CCLM). 2016;54(10):1545–59.

6. Kounis NG, etal. Kounis syndrome: a new twist on an old

disease. Fut Cardiol. 2011;7(6):805–24.

7. Helbling A, etal. Incidence of anaphylaxis with circulatory

symptoms: a study over a 3-year period comprising 940 000

Fig. 2 Therapeutic algorithm

for perioperative Kounis

syndrome. HR heart rate, BP

blood pressure, PCI percutane-

ous coronary intervention, ICU

intensive care unit

Breast Cancer

1 3

inhabitants of the Swiss Canton Bern. Clin Exp Allergy.

2004;34(2):285–90.

8. Abdelghany M, etal. Kounis syndrome: a review article on

epidemiology, diagnostic findings, management and compli-

cations of allergic acute coronary syndrome. Int J Cardiol.

2017;232:1–4.

9. Lopez PR, Peiris AN. Kounis syndrome. South Med J.

2010;103(11):1148–55.

10. Biteker M. A new classification of Kounis syndrome. Int J Car-

diol. 2010;145(3):553.

11. Akyel A, etal. Late drug eluting stent thrombosis due to acem-

etacine: type III Kounis syndrome: kounis syndrome due to

acemetacine. Int J Cardiol. 2012;155(3):461–2.

12. Kaartinen M, Penttilä A, Kovanen PT. Accumulation of acti-

vated mast cells in the shoulder region of human coronary ath-

eroma, the predilection site of atheromatous rupture. Circula-

tion. 1994;90(4):1669–788.

13. Gázquez V, etal. Kounis syndrome: report of 5 cases. J Investig

Allergol Clin Immunol. 2010;20(2):162–5.

14. Wickman M. When allergies complicate allergies. Allergy.

2005;60:14–8.

15. Kounis NG. Kounis syndrome (allergic angina and allergic

myocardial infarction): a natural paradigm? Int J Cardiol.

2006;110(1):7–14.

16. Mazarakis A, et al. Cefuroxime-induced coronary artery

spasm manifesting as Kounis syndrome. Acta Cardiol.

2005;60(3):341–5.

17. Simons FER, etal. World allergy organization anaphylaxis

guidelines: 2013 update of the evidence base. Int Arch Allergy

Immunol. 2013;162(3):193–204.

18. Roffi M, etal. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of

acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without

persistent ST-segment elevation: task force for the management

of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without per-

sistent ST-segment elevation of the european society of cardiol-

ogy (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2016;37(3):267–315.

19. Simons FER, et al. World allergy organization anaphy-

laxis guidelines: summary. J Allergy Clin Immunol.

2011;127(3):587–593.e22.

20. Kristensen SD, Aboyans V. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the man-

agement of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting

with ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:119–77.

21. Barthelmes L, etal. Adverse reactions to patent blue V dye–The

NEW START and ALMANAC experience. Eur J Surg Oncol

(EJSO). 2010;36(4):399–403.

22. Paulinelli RR, etal. A prospective randomized trial comparing

patent blue and methylene blue for the detection of the sentinel

lymph node in breast cancer patients. Revista da Associação

Médica Brasileira. 2017;63(2):118–23.

23. Guo W, etal. Evaluation of the benefit of using blue dye in

addition to indocyanine green fluorescence for sentinel lymph

node biopsy in patients with breast cancer. World J Surg Oncol.

2014;12(1):290.

24. Karakatsanis A, etal. The Nordic SentiMag trial: a comparison

of super paramagnetic iron oxide (SPIO) nanoparticles versus

Tc 99 and patent blue in the detection of sentinel node (SN) in

patients with breast cancer and a meta-analysis of earlier stud-

ies. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2016;157(2):281–94.

25. Peek MC, et al. Is blue dye still required during sentinel

lymph node biopsy for breast cancer? Ecancermedicalscience.

2016;10:674. https ://doi.org/10.3332/ecanc er.2016.674.

Publisher’s Note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to

jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.