PROTOZOOLOGY - ORIGINAL PAPER

Detection and characterization of the Isospora lunaris infection

from different finch hosts in southern Iran

Ehsan Rakhshandehroo

1

& Fatemeh Fakhrahmad

1

& Jalal Aliabadi

1

& Amir Mootabi Alavi

1

& Mohammad Asadpour

1

Received: 31 July 2020 /Accepted: 2 November 2020

#

Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature 2020

Abstract

This study was conducted to investigate the Isosporoid protozoan infections in finch types. Fecal samples were collected from

marketed domestic Java sparrows (Lonchura oryzivora), colored and white Zebra finch (Taeniopygia guttata), and European

goldfinch (Carduelis carduelis) in southern Iran. The coccidial oocysts were recovered and investigated according to the

morphological features and the ribosomal gene markers. Additionally, a challenge infection was conducted with 5 × 10

4

and

5×10

3

sporulated oocysts in four java sparrows to estimate the clinical manifestations. Based on the morphology, the oocysts of

Isospora lunaris were identified in all sampled bird types; however, the molecular method revealed the isolates had considerable

similarities with some of Isospora and systemic Isospora-like organisms named as Atoxoplasma. Phylogenetic data also con-

structed an Atoxoplasma/Isospora clade with high sequence identities. High dose of the challenge with the parasite led to severe

depression and sudden death, but it did not coincide with remarkable lesions and parasitic invasion in visceral organs. Contrary to

molecular results, this feature is consistent with the common Isospora infections in passerines and differs from those described

for Atoxoplasma species. Because of the prevalence, possibility of transmission, and clinical consequences, preventive measures

are necessary to avoid outbreaks of isosporoid infections among finch type birds.

Keywords Isospora

.

Finch

.

Ribosomal rRNA gene

.

Atoxoplasma

Introduction

Members of the g enus Isospora are the most common

coccidian parasites reported from passerine bird s (Dolnik

2006). Different species of the parasite have been introduced

with a wide distribution in the past (Berto et al. 2011;

Schoener et al. 2013). In recent years, some new species have

been described using morphological and molecular assays on

the sporulated oocysts. Owing to overlapping values for some

morphometric characteristics, molecular investigations were

involved for diagnosis. In passerine birds, an Isospora-like

coccidian parasite, named the Atoxoplasma, was proved to

develop an extra-intestinal systemic isosporosis with severe

diseases (Levine 1982). Despite differences in pathogenicity,

some molecular data have proposed integration of the

Atoxoplasma genus in the Isospora group (Schrenzel et al.

2005). According to available information, the ribosomal gene

region has received more considerations to classify isosporoid

species; however, the validity of the groups should be more

investigated in different passerine hosts.

In the finch host, a number of Isospora species have been

reported. The small tree finch (Camarhynchus parvulus)

(McQuistion and Wilson 1988), lesser seed-finch

(Oryzoborus angolensis)(TrachtaeSilvaetal.2006), saffron

finch (Sicalis flaveola) (Coelho et al. 2011), captive-bred red-

browed finch (Neochmia temporalis) (Yang et al. 2016), and

Java finch (Lonchura oryzivora) (Tokiwa et al. 2017)have

been reported to be infected with isosporoid protozoans. The

Java sparrow or Java finch (Lonchura oryzivora) is a species

of passerine birds belonging to the family Estrildidae. This

species is natively endemic in Indonesia; however, popula-

tions are spread in many regions aroun d the world. In

L. oryzivora, previous studies described two Isospora species,

i.e., I. paddae (Amoudi 1988) with a high mortality rate and

I. lunaris (Tokiwa et al. 2017) with the sign of diarrhea and

death in some cases. I. lunaris was also characterized to

Section Editor: Nawal Hijjawi

* Ehsan Rakhshandehroo

Rakhshandehroo@Shirazu.ac.ir

1

Department of Pathobiology, School of Veterinary Medicine, Shiraz

University, P.O. Box 71441-69155, Shiraz, Iran

Parasitology Research

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-020-06962-3

invade extra-intestinal merozoite-like organisms in mononu-

clear leukocytes. This behavior of the parasite is likely the

cause of unexpected illnesses in passerine birds.

In Iran, different types of finch and other passerines have

been traditionally reared and sold in markets. Regarding the

importance and pathogenicity of coccidial infections in this

type of birds, we examined the presence and clinical conse-

quence of isosporoid parasites in finches in southern Iran.

Materials and methods

Collection of oocysts

The sampling was carried out from at least 7 local bird markets

in Shiraz City (29.59° N; 52.58° E), South of Iran. At any

location, different types of passerine birds were separately

maintained in cages for sale. Fresh fecal samples were collect-

ed from the bottom of at least 5 individual cages of finches,

including domestic Java sparrows (Lonchura oryzivora)(n =

3; n shows the number of markets sampled), colored and white

Zebra finch (Taeniopygia guttata)(n =2),andEuropeangold-

finch (Carduelis carduelis)(n = 2). Feces were put into tubes

containing 2.5% potassium dichromate solution (K

2

Cr

2

O

7

),

and the presence of oocysts was determined by direct micro-

scopic examination. Samples positive for coccidian oocysts

were placed in Petri dishes containing a thin layer of 2.5%

(w/v)K

2

Cr

2

O

7

solution and kept in an incubator (27 °C, ≥

70% humidity) to facilitate oocyst sporulation. The sporula-

tion was monitored for approximately 7 days (mostly at the

first 2 days) until the highest percent sporulation was

achieved. The sporulated oocysts were then recovered by flo-

tation in salt saturated solution, washed with normal saline to

remove the saturated material, and subjected to morphological

measurements using a binocular microscope with an ocular

micrometer (Nikon, H.K.W.15X).

Genomic extraction

The sporulated oocysts were washed with normal saline for at

least 3 times. The oocyst wall was broken by vortexing in the

presence of glass beads with 2 mm in diameter for at least

5 min. The sporocyst or sporozoite material was then recov-

ered from the glass beads, pe lleted by centrifugation at

1500×g and subjected to DNA extraction using a commercial

kit (MBST, Iran).

PCR amplification

Ribosomal RNA genes were used to identify the species of the

oocysts. The 18S rRNA gene was amplified using the primers

EiF1 (5′-GCTTGTCTCAAAGATTAAGCC-3′)(Poweretal.

2009) and EIR3 (5′-ATGCATACTCAAAAGATTACC-3′)

(Yang et al. 2012). The PCR program included 94 °C for

3 min, followed by 40 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 58 °C for

30 s, and 72 °C for 2 min and a final extension of 72 °C for

5 min. Partial fragment of the 28S ribosomal RNA gene (28S

rRNA) was also amplified using primers 28SIoF (5′-GTTC

GTTTGGCYCCACTTT-3′ ) and 28SloR (5′ -AACG

CTTCGCYACGATCC-3′) (Tokiwa et al. 2017). PCR cycling

conditions were 1 cycle of 94 °C for 3 min, followed by

45 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 57 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for

2 min and a final extension of 72 °C for 4 min. The expected

amplicons were visualized by electrophoresis in 1.2% (w/v)

Tris-acetate/EDTA agarose gel under ultraviolet illumination.

The PCR products of expected sizes were sequenced from

each assay on an ABI 3730 DNA analyzer (Bioneer, Korea).

Phylogenetic analysis

To determine the phylogenic positions based on each locus,

the s equences were compared to available homol ogous

isosporoid species using the BLAST search in the GenBank.

Multiple-sequence alignment was performed using the Clustal

W program in the MEGA software version 10.1. Gaps and

ambiguous positions were edited manually. Data were also

applied to construct the phylogenetic trees using the maxi-

mum likelihood method (Kumar et al. 2018). The most appro-

priate model for the best fit to the data was estimated. The

Kimura 2-parameter with gamma-distributed substitution

rates was found to be the best choice. Bootstrap analyses were

conducted using 1000 replicates to estimate the reliability of

the inferred tree. The sequence identity rates were also esti-

mated using the BioEdit software (Hall 1999).

Clinical experiment and infection confirmation

To identify the clinical consequences of the infection, four

Java sparrows, all under 1 year of age, were also purchased

and subjected to an experimental infection. All the birds were

negative for gastro-intestinal parasites (coccidian or helminth

infections) and were separately kept for 10 days to adapt the

new environment. They were then orally inoculated with 5 ×

10

3

(n =2)and5×10

4

(n = 2) sporulated oocysts previously

obtained from Java sparrows. Along with monitoring the clin-

ical signs, fecal samples were also checked daily for oocyst

excretion at least 30 days after the inoculation (dpi). Venous

blood samples were also taken from the jugular vein at the end

of the first 7 dpi, and thin-blood smear was prepared stained

by the Giemsa. Since those two birds infected with a high

challenge dose died, they necropsied and the internal organs

were inspected. To detect and confirm the presence of any

developmental cycles of the parasite, the small intestine and

liver tissues were separately removed and fixed in 10%

neutral-buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at

Parasitol Res

a thickness of 4 to 6 μm, and stained with hematoxylin and

eosin (H&E).

This experiment was authorized and approved by the

Iranian animal ethics c ommittee i n Shiraz University

Research Council (IACUC, No: 4687/63).

Results

Morphologic data

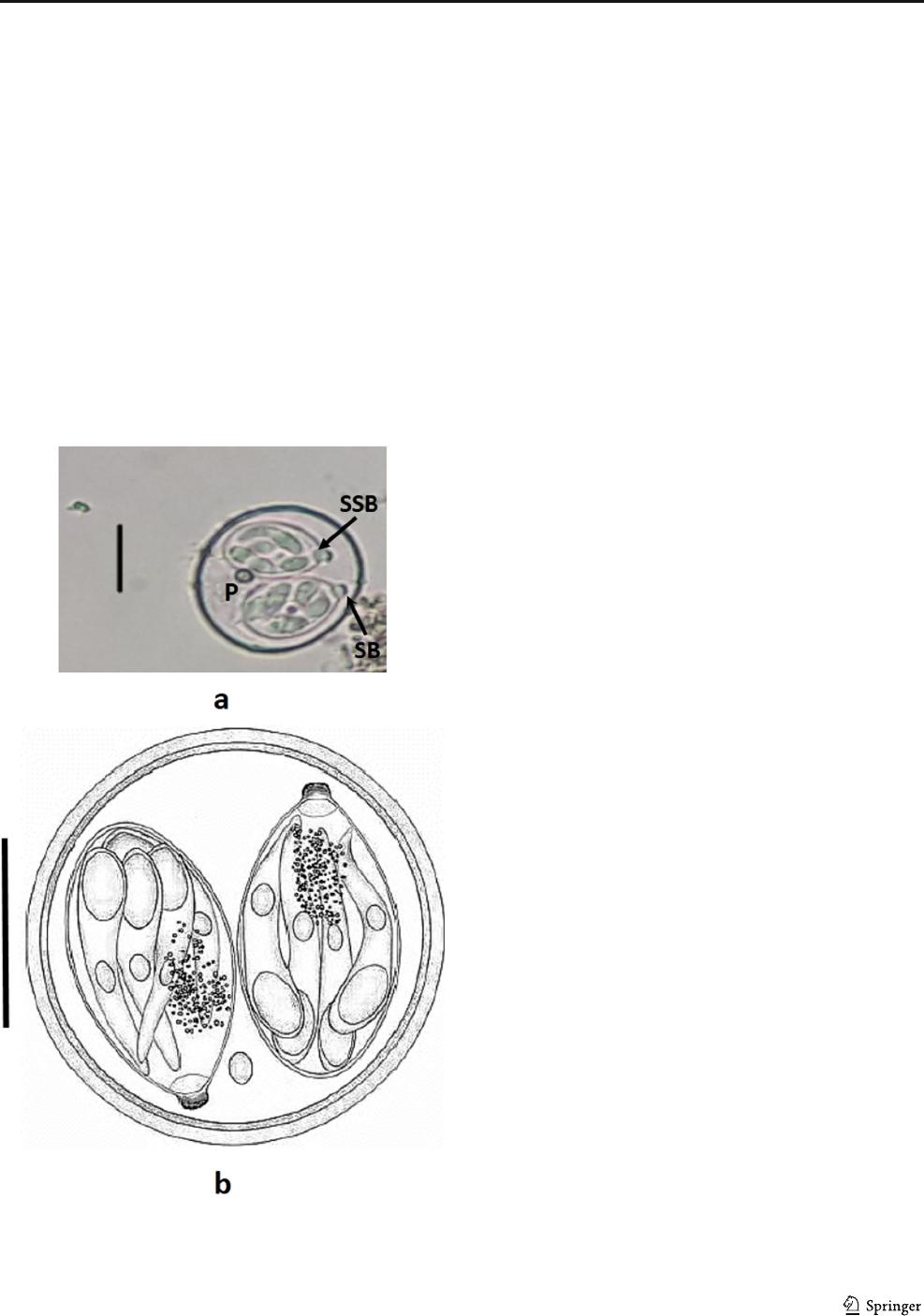

The overall morphology of the sporulated oocysts was similar

in the three types of finch. The oocysts ( n = 37), with the

characteristics of the Isospora species (Fig. 1), were spherical

to subspherical in shape, 22.5 × 20.6 (18–26 × 16–24) in size,

with a shape index (length/width) of 1.08; a smooth bilayered

wall consisting of a relatively green outer layer and a dark

green inner layer, lacked micropyle and residuum; however,

a single polar granule was present. The sporocyts were ovoid,

14.4 × 10.1 (10–17 × 7–13) in size, with a smooth colorless

wall, and a prominent knob-like stieda body and r ounded

substieda body at the anterior part. The sporocyst residuum

was composed of numerous granules of small size, which was

loosely clustered and scattered between the sporozoites. The

sporozoites lied parallel to the sporocyst longitudinal axis.

Table 1 presents a detailed morphological comparison on

the available descriptions of Isospora spp. in finch hosts.

According to available information, our isolates were most

similar to the I. lunaris described from Java sparrows in

Japan (Tokiwa et al. 2017) and were simply distinguished

from the others. However, compared to the Japanese report,

the present samples had a different oocyst wall color (green

instead of colorless), a relatively more prominent stieda body

as well as sporocyst residual bodies with more diffused and

smaller granules.

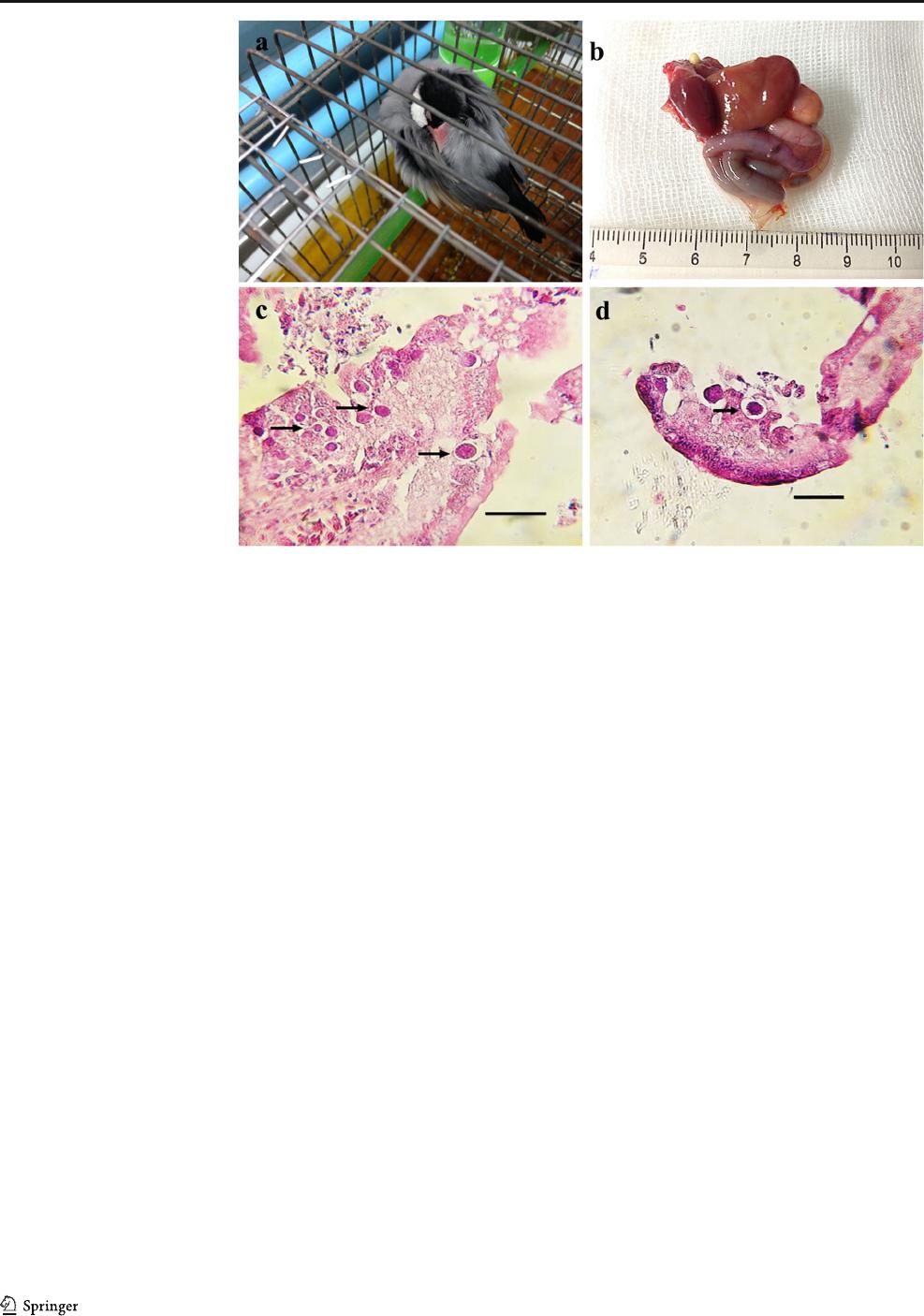

Clinical features

Birds infected with 5 × 10

4

oocysts presented signs of severe

depression, dyspnea, lethargy and anorexia from 6 and 7 dpi,

and sudden death, along with a large number of oocysts shed-

ding at 8 and 10 dpi (Fig. 2a). Dead sparrows were autopsied,

and the internal organs were removed. No gross lesions, en-

largement, or color changes were seen (Fig. 2b). Despite some

postmortem changes, the extranuclear developing gameto-

cytes were seen in the parasitophorous vacuoles in the small

intestines (Fig. 2c, d). On the contrary, no signs of parasite

invasion were seen in blood cells and the liver. The two java

finches with lower oral infection did not exhibit remarkable

clinical signs. High amounts of oocysts were first detected in

feces from 5 and 9 dpi and disappeared at approximately 26

and 40 dpi, respectively.

Molecular analysis

Fragments of approximately 1500 and 800 bps were achieved

for 18S and 28S rRNA genes, respectively. The sequences

obtained for different bird types for both gene regions had

near complete identities (ranged from 99 to 100%).

Representative sequences were deposited in the GenBank da-

tabase under the accession numbers MT237177 (18S rDNA)

and MT237182 (28S rDNA) and aligned with the data avail-

able from the closest coccidian species in passerines; however,

due to variations in length and the sites amplified, particularly

for the 18S locus, sequences were trimmed before

comparisons.

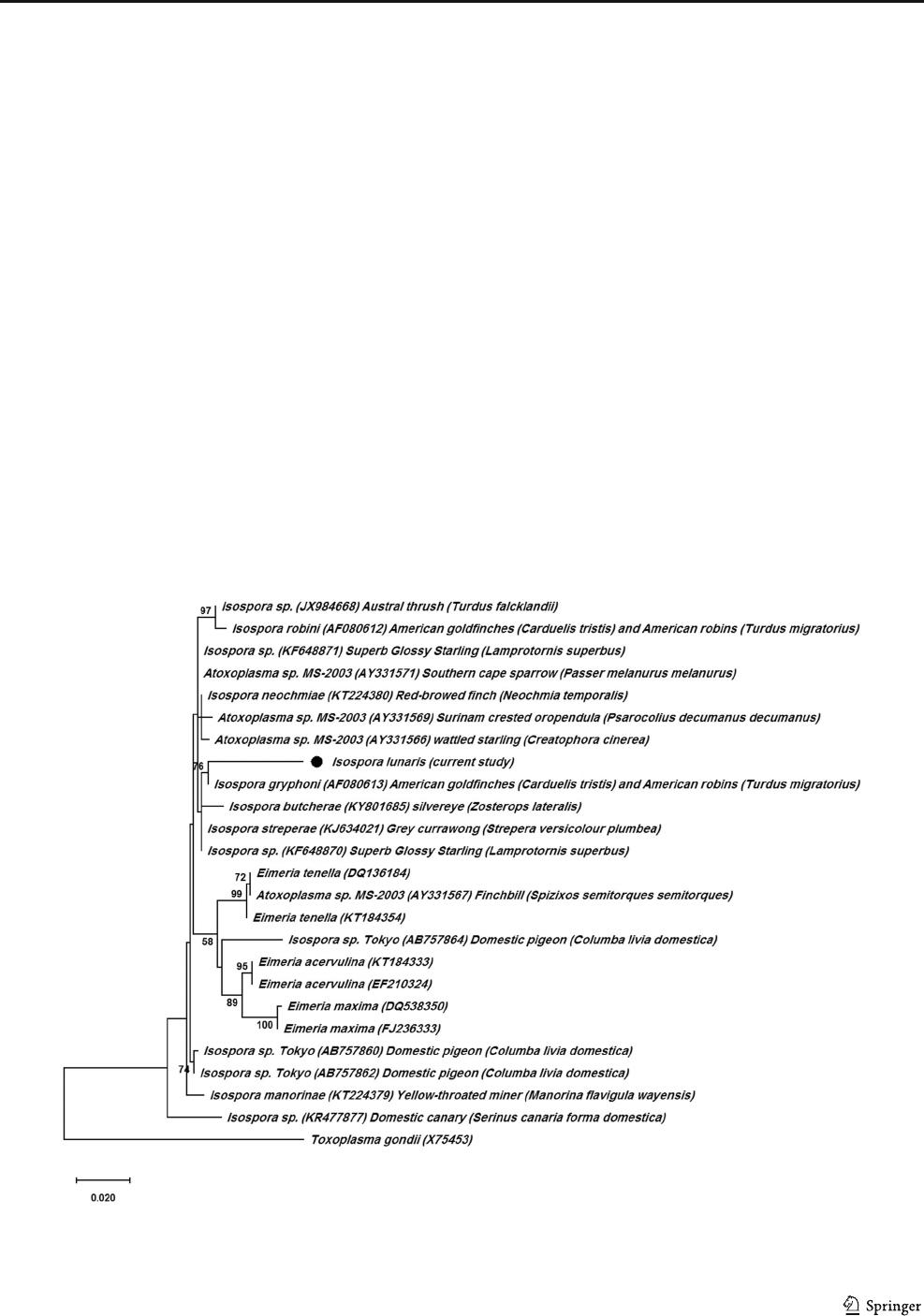

The phylogenetic tree derived from the 18S rRNA gene

region did not show species-specific clustering. Our isolates

were placed into the Atoxoplasma/Isospora clade (Fig. 3)with

relatively high homologies. Despite the Eimeria species, this

Fig. 1 Photograph (a) and line drawing of sporulated oocysts of Isospora

lunaris from Java sparrow host (b); P, polar granule; SB, stieda body;

SSB, substieda body. Scale bar ~ 10 μm

Parasitol Res

Table 1 Comparative morphologic characteristics of oocysts described from different finch hosts

Isospora species Host Oocyst

Shape Measurements

(μm)

Shape

index

Wall Polar

granule

Oocyst

residuum

I. lunaris

(Present study)

Java sparrow and common Myna Spherical to subspherical 22.5 × 20.6

(18–26 × 16–24)

1.08 Bilayered Present Absent

I. lunaris Java sparrow

(Lonchura oryzivora)

Spherical 22.1 × 20.7

(20–25 × 20–22.5)

1.07 Bilayered Present Absent

I. paddae Java sparrow

(Lonchura oryzivora)

Spherical 44 × 41.2

(41.5–45.5 × 40.3–41.5)

Not defined Bilayered A bsen t Absent

I. geospizae Ground finch

(Geospiza fuliginosa)

(Geospiza fortis)

Spherical to subspherical 15.5 × 14.5

(13–17 × 12–17)

1.05 One layered Present (large) Absent

I. daphnensis Ground finch

(Geospiza fuliginosa)

(Geospiza fortis)

Ellipsoidal 27.3 × 23.6

(22–30 × 20–27)

1.2 Bilayered Present Absent

I. exigua Small tree finch

(Camarhynchus parvulus)

Spherical to subspherical 20.4 × 20.1

(20–23 × 18–23)

1.0 One layered Absent Absent

I. rotunda Small tree finch

(Camarhynchus parvulus)

Spherical to subspherical 21.8 × 20.9

(20–24 × 19

–23)

1.0 One layered Present (large) Absent

I. fragmenta Small tree finch

(Camarhynchus parvulus)

Spherical to subspherical 25.3 × 24.2

(24–27 × 23–25)

1.0 One layered Present splinter-like Absent

I. temeraria Small tree finch

(Camarhynchus parvulus)

Spherical to subspherical 25.4 × 2 1.1

(2 1–30 × 17–23)

1.2 One layered Large round Absent

I. cetasiensis Saffron finch

(Sicalis flaveola)

Subspherical to ellipsoidal 23.1 × 21.6

(19–27 × 19–26)

1.1 Bilayered Absent Absent

I. sicalisi Saffron finch

(Sicalis flaveola)

Subspherical to ellipsoidal 27.5 × 25.2

(25–29 × 22–28)

1.1 Bilayered Absent Absent

I. indonesianensis chestnut Munia,

(Lonchura malacca)

Spherical 41.8 × 39.6

(39.3–43.6 × 37–40.8

Not defined Bilayered A bsen t Absent

I. neochmiae Red-browed finch

(Neochmia temporalis)

Spherical 18.3 × 18.2

(18.2–18.9 × 18.2–18.6)

1.5 Bilayered Present Absent

I. curio Lesser seed-finch

(Oryzoborus angolensis)

Spherical to subspherical 24.6 × 23.6

(22–26 × 22–25)

1.04 Bilayered Absent Absent

I. braziliensis Lesser seed-finch

(Oryzoborus angolensis)

Spherical to subspherical 17.8 × 16.9

(16–19 × 16–18)

1.06 One layered Absent Absent

I. paranaensis

lesser seed-finch

(Oryzoborus angolensis)

Elliptical 24.3 × 19.8

(22–26 × 18–22)

1.22 One layered Present Absent

I. vagoi Zebra finch

(Taeniopygia guttata)

Spherical to subspherical 24.6 × 21.5 Not defined Not defined Present Present

I. loaei Javan munia (finch)

(L. leucogastroides)

Spherical 20.6 × 18.5

(18.5–22 × 16.5–20)

1.11 Bilayered Absent Absent

Parasitol Res

Table 1 (continued)

Isospora species Sporocyst

Shape Measurements

(μm)

Stieda

body

Substieda body residuum Reference

I. lunaris

(Present study)

Ovoid 14.4 × 10.1

(10–17 × 7–13)

Prominent knob-like Present (rounded) Scattered Present study

I. lunaris Ovoid 14.1 × 9.8

(12.5–15 × 7.5–10)

Nipple like Present (rounded) Scattered Tokiwa et al. 2017

I. paddae Ovoid 24 × 16.2

(22.8–24.5 × 14.7–17)

Knob-like Absent Diffused Amoudi 1988

I. geospizae Ovoid 10 × 7.5

(10–12 × 6–9)

Small rounded Small Compact irregular-shaped McQuistion and Wilson 1989

I. daphnensis Ovoid 15.2 × 10.2

(15–16 × 9–11)

Nipple like Small Compact irregular-shaped McQuistion 1990

I. exigua Ovoid 14 × 9.5

(13–15 × 8–10)

small Small Compact irregular-shaped McQuistion and Wilson 1988

I. rotunda Ovoid 15 × 9.7

(13–16 × 9–10)

Knob-like Prominent round, consolidated McQuistion and Wilson 1988

I. fragmenta Piriform 15.4 × 11.5

(14–17 × 1 I-12)

Knob-like Prominent Compact irregular-shaped McQuistion and Wilson 1988

I. temeraria Piriform 15 × 10

(14–15 × 9–11)

Knob-like Prominent Round, consolidate McQuistion and Wilson 1988

I. cetasiensis Ovoid 15.1 × 10.9

(13–19 × 10

–13)

Knob-like Rounded Scattered granules Coelho et al. 2011

I. sicalisi Ellipsoid 17.2 × 11.7

(15–19 × 11–12)

Knob-like Trapezoid Scattered Coelho et al. 2011

I. indonesianensis Ovoid 27.1 × 16.8

(25.6–28.4 × 15.2–18.5)

Present Not defined Present Amoudi 1988

I. neochmiae Ovoid 13.3 × 8.6

(9.5–16.4 × 6.8–10.0)

Present Absent Scat ter ed, Different size Yang et al. 2016

I. curio Ovoid 13.2 × 10.9

(15–17 × 10–13)

Present Absent S catter ed Trachta e Silva et al. 2006

I. braziliensis Ellipsoid 13.2 × 10.8

(12–14 × 9–12)

Barely visible Absent Scattered Trachta e Silva et al. 2006

I. paranaensis Ovoid 15.7 × 10.1

(14–18 × 8–12)

Present Present Small, scattered Trachta e Silva et al. 2006

I. vagoi Ovoid 14.2 × 9.4 Present Not defined Present Blanc and Grulet 1985

I. loaei Ovoid 13.1 × 9.3

(12–14.5 × 8.5–10)

Present Absent Present Amoudi 1994

Parasitol Res

group was not supported by high bootstrap values. The closest

relationship (96.5%) was observed with I. grypho ni

(AF080613) separated from American goldfinches

(Carduelis tristis) and American robins (Turdus migratorius).

Using the records for other finch hosts, we re vealed 96%

identity with I. neochmiae (KT224380) from the red-browed

finch (Neochm ia temporalis ) in Australia. Additi onally,

Atoxoplasma spp. isolated from wattled starling

(Creatophora cinerea) (AY331566) (95.6%), Surinam crest-

ed oropendula (Psarocolius decumanus decumanus)

(AY331569) (95.8%), and Southern cape sparrow (Passer

melanurus melanurus) (AY331571) (96.1%) were more phy-

logenetically related to our isolates.

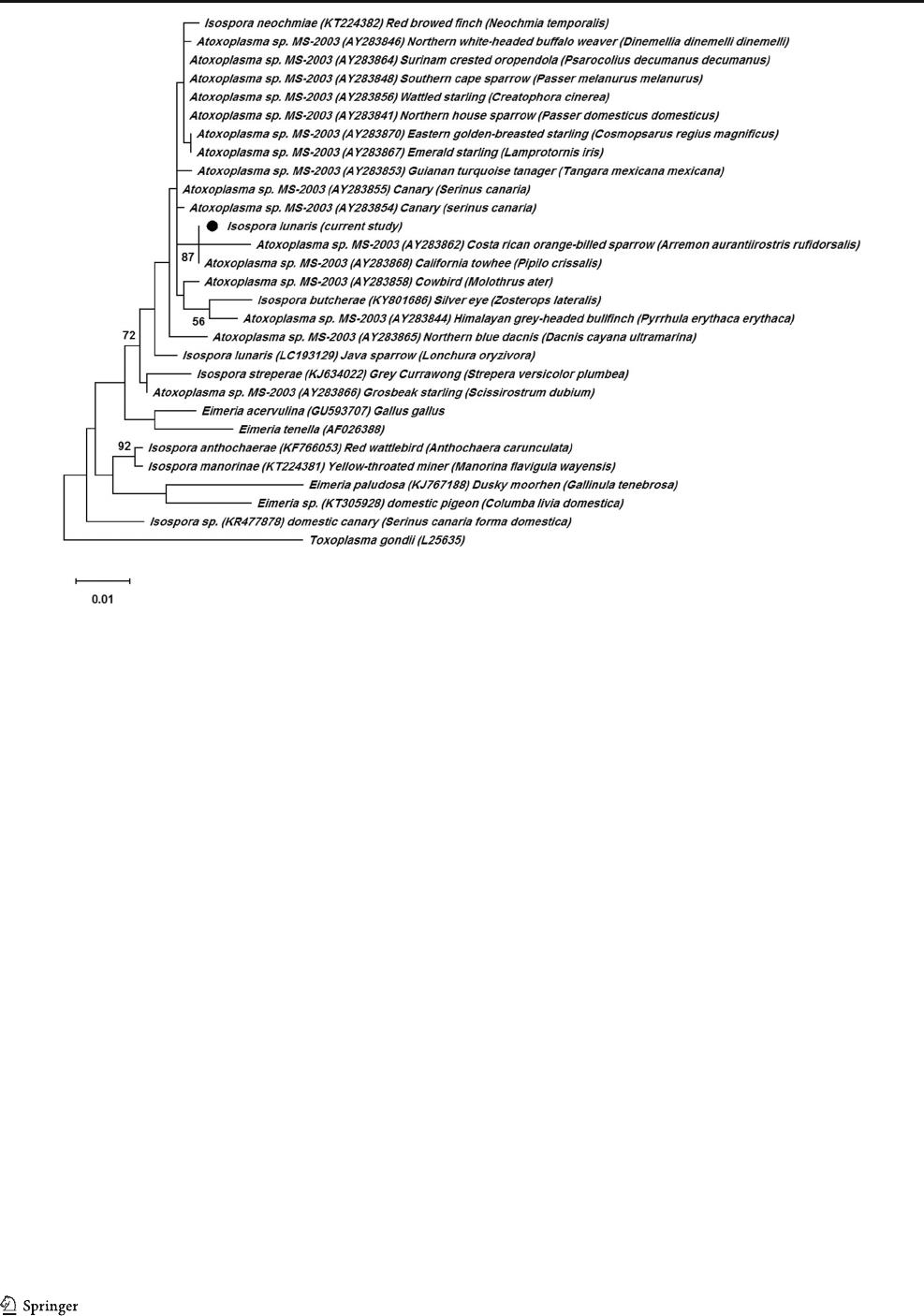

Based on the 28S rRNA gene, the present specimens

exhibited 98.6% identity with the only report for I. lunaris

(LC193129) from J apan, and 99% with I. neochmiae

(KT224382). Interestingly, in line with the phylogenetic

data (Fig. 4), many of the Atoxoplasma species exhibited

near complete similarities with our isolates, including

California towhee (Pipilo crissalis( (AY283856)

(99.5%), Wattled starling (Creatophora cinerea)

(AY283856) (99.3%), Canary (Serinus canaria)

(AY283854) (99.3%), Northern house sparrow (Passer

domesticus domesticus) (AY283841) (99.3%), Surinam

crested oropendola ( Psarocolius decumanus decumanus)

(AY283864) (9 9.3%), So uthern cape sparrow (Passer

melanurus melanurus) (AY283848) (99.3%), Eastern

golden-breasted starling (Cosmopsarus regius magnificus)

(AY283869) (99.1%), Canary (Serinus canaria)

(AY283855) (99.1%), and Northern white-headed buffalo

weaver (Dinemellia dinemelli dinemelli) (AY28384 6)

(99.1%).

Discussion

In passerine birds, isosporoid species have been tradition-

ally described by their morphological characters. Oocyst

dimensions are t he main feature, but the presence or ab-

sence and shape of oocyst inner structures are also helpful

when overlapping m easurements cause misidentification.

In the present study, the examined oocysts were mostly

close t o the I. lunaris descri be d i n a previo us work from

Java sparrows in Japan (Tokiwa et al. 2017). Differences

in morphological features were not significant enough to

assign them as a new species. Slight variations sometimes

occur due to the sporulation process and the position of

the oocysts that are examined under the microscope

(Coelho et al. 2011). As Table 1 shows, our isolates w ere

alsomatchedindimensionstoI. cet as i ens is reported from

the saffron finch (Sicalis flaveola) from Brazil (Coelho

et al. 2011). In comparison, I. cetasiensis had a larger

range for oocyst and sporocyst size and lacked the polar

granule.

In the past, arguments on t he isosporoid infections in

passerines indicated to a type of systemic Isospora with

extra-intestinal stages, named Atoxoplasma (Levine 1982;

Cushing et al. 2011). Atoxoplasma is considered the tissue

Fig. 2 The infection with high

dose challenge with I. lunaris in

Java sparrow. a Signs of severe

depression at about 6 dpi. b Gross

view of visceral organs. c, d

Developing gametocytes (arrows)

surrounded by a vacuole in the

small intestine. H&E staining.

Scale bar ~ 40 m

Parasitol Res

invasive (systemic) form of the coccidian Isospora (Long

1993). The asexual divisions occur in both intestinal and

lymphoid-m acrophage ce lls of passer ine birds (Lev ine

1982). Furthermore, the Atoxoplasma infection is

established as a chronic infection in canaries, while the

common Isospora species produces a self-limited disease

(Box 1981). In the present study, self-restriction in fecal

oocyst expulsion and lack of developing parasites in liver

and blood samples were not in agreement with the sys-

temic isosporosis . S ome recent studi es h ave r epresented

only the intestinal stages for I. neochmiae in the r ed-

browed finch (Neochmia temporalis) ( Yang et al. 2016)

and I. bioccai (Luna-Castrejón et al. 2018)andI. canaria

(Şaki and Özer 2012) in the canary (Serinus canaries)

host. On the contrary, investigations depicted merozoite-

like organisms i n mononuclear cells in blood (Tokiwa

et al. 2017) and infiltrated lymphocytes in duodenum

and liver tissues (Gosbell et al. 2020) of some finch types.

This variation is mainly due to the difference between the

invasive entities of the isosporoid species. However, the

lower amount of merozoites occurred in lymphocytes in a

short period is possibly a reason for their misdiagnoses.

According to molecular analysis, t he phylogenetic con-

structions were relat ively consistent wit h one another,

corroborating the almost complete genetic identities be-

tween the Isospora an d Atoxoplasma species. Owing to

rare mol ecular data o n those parasites, we were unable

to classify our isolates with one species. However, con-

sistent with our finding, monophyletic relevance between

the two species was demonstrated (Yang et al. 2016;

Tokiwa et al. 2017; Matsubara et al. 2017). Based on

the r ibosomal gene records, the isosporoid species in pas-

serine birds are a monophyletic group with a significant

diversity. Consequently, it was suggested that the

Isospora, whether isolated from the systemic lesions or

separated from fecal oocysts, would be referred to a ho-

mogeneous group of individuals in a single taxon

(Schrenzel et al. 2005). Therefore, the present molecular

indices are not capable of distinguishing between com-

mon and systemic isosporosis.

Many of newly described isosporoid species in passerines

have characterized based on few morphologic or morphomet-

ric variations. According to molecular phylogeny, those spe-

cies set also on a separate branch. In contrast, as shown in this

study, the phylogenetic relationships between the parasites are

not comparable at different gene regions. Variations in phy-

logenies proposed in recent studies (Yang et al. 2014; Yang

et al. 2016; Tokiwa et al. 2017; Liu et al. 2019)aswellashigh

Fig. 3 Maximum likelihood tree inferred from partial 18S rRNA gene sequences. Numbers at nodes show bootstrap support 1000 replicates (> 50%).

Scale bar points the number of nucleotide substitutions per site

Parasitol Res

molecular identities with the other Isospora reports indicate

the uncertainty of molecular results to specify the parasite or to

compare with morphologic classification.

In this study, the oocysts of the same species were identi-

fied in all bird types sampled from families Estrildidae and

Fringillidae. This implies the possibility of intra- and inter-

familial transmission among the examined birds. Previously,

the coccidial agents were characterized to be highly host and

species specific in passerine birds (Berto et al. 2011). Some

earlier studies failed to transmit the specific Isospora infection

between sparrows and canaries (Box 1981). Nevertheless, the

present study and a few recent observations have criticized the

old view on the concept of intra-familial specificity.

Identification of I. bioccai in a canary host, which was first

described in greenfinch species ( Chloris sinica) (Luna-

Castrejón et al. 2018), and suggestion of sparrows as the cause

of systemic isosporosis in green and gold finches (Gosbell

et al. 2020), are consistent with the transmission hypothesis.

If the inter-familial transmission is proved to occur between

passerine birds, the outbreaks of the isosporoid parasites are

expected in the future.

Regardless of the classification, the current infection in

different finch species and the possibility of severe clinical

manifestations demo nstrate the importance of preventive

measures in passerine birds, particularly in those that commu-

nicate with or are placed in the finch group.

Conclusions

The oocysts of I. lunaris were recognized in the fecal samples

of some finch species, which are popular passerines in the

world. The oocysts were morphologically similar to the de-

scriptions previously reported for this species from Java spar-

rows. In studying molecules, the present samples constructed

an Isospora/Atoxoplasma clade with considerable similarities

between the two genera. Owing to the prevalence in different

types of birds examined and the pathogenic entity of the par-

asite, preventive measures should be taken to decrease the

transmission risk in passerine birds.

Funding This study was thankfully supported by a grant from Shiraz

University (Grant No. 1/2019).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of

interest.

Fig. 4 Evol ut ionary relationship s of I. l unaris inferred by analysis of 28S rRNA gene sequences. Percentage support ( > 5 0%) from 1000

pseudoreplicates is indicated at the left of the support node

Parasitol Res

Ethical approval Experimental procedures were approved by the Iranian

animal ethics committee in Shiraz University Research Council (IACUC,

No: 4687/63).

References

Amoudi MA (1988) Two new species of Isospora from Indonesian birds.

J Protozool 35:116–118

Amoudi MA (1994) Four new species of the coccidian parasite Isospora

(Apicomplexa, Eimeriidae) from Malayan birds. Zool Stud 33:165–

169

Berto BP, Flausino W, McIntosh D, Teixeira-Filho WL, Lopes CW

(2011) Coccidia of new world passerine birds (Aves:

Passeriformes): a review of Eimeria Schneider, 1875 and Isospora

Schneider, 1881 (Apicomplexa: Eimeriidae). Syst Parasitol 80:159–

204

Blanc É, Grulet O (1985) Isospora vagoi n. sp. parasite de Poephila

guttata (Mandarin d'élevage). Bull Mus Natn Hist Nat Paris 4:

401–405

Box ED (1981) Isospora as an extraintestinal parasite of passerine birds. J

Protozool 28:241–246

Coelho CD, Berto BP, Neves DM, de Oliveira VM, Flausino W, Lopes

CWG (2011) Two new Isospora species from the saffron finch,

Sicalis flaveola in Brazil. Acta Parasitol 56:239–244

Cushing TL, Schat KA, States SL, Grodio JL, O’Connell PH, Buckles EL

(2011) Characterization of the host response in systemic isosporosis

(atoxoplasmosis) in a colony of captive A merican goldfinches

(Spinus tris tis) and house sparrows (Pass er do mesticus ). Vet

Pathol 48:985–992

Dolnik OV (2006) The relative stability of chronic Isospora sylvianthina

(Protozoa: Apicomplexa) infection in blackcaps (Sylvia atricapilla):

evaluation of a simplified method of estimating isosporan infection

intensity in passerine birds. Parasitol Res 100:155–160

Gosbell MC, Olao gun OM, Luk K, Noo rmohammadi AH (2020)

Investigation of systemic iso sporosis outbreaks in an aviary of

greenfinch (Carduelis chloris) and goldfinch (Carduelis carduelis)

and a possible link with local wild sparrows (Passer domesticus).

Aust Vet J 98:338–344

Hall TA (1999) BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment

editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucl Acids

Symp Ser 41:95–98

Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K (2018) MEGA X:

molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing plat-

forms.MolBiolEvol35:1547–1549

Levine ND (1982) The genus Atoxoplasma (Protozoa, Apicomplexa). J

Parasitol 68:719–723

Liu D, Brice B, Elliot A, Ryan U, Yang R (2019) Isospora coronoideae n.

sp.(Apicomplexa: Eimeriidae) from the Australian raven (Corvus

coronoides) (Passeriformes: Corvidae) (Linnaeus, 1758) in

Western Australia. Parasitol Res 118:2399–2408

Long PL (1993) Avian coccidiosis. In: Kreier JP (ed) Parasitic protozoa.

Academic Press Ltd., London, pp 1

–88

Luna-Castrejón LP, Ravines-Carrasco L, Salgado-Miranda C, Soriano-

Vargas E (2018) The canary Serinus canaria (Passeriformes:

Fringillidae) as a new host for Isospora bioccai in Mexico. Int J

Parasitol Parasites Wildl 7:445–449

Matsubara R, Fukuda Y, Murakoshi F, Nomura O, Suzuki T, Tada C,

Nakai Y (2017) Detection and molecular status of Isospora sp. from

the domestic pigeon (Columba livia domestica). Parasitol Int 66(5):

588–592

McQuistion TE (1990) Isospora daphnen sis n. sp. (Apicomplexa:

Eimeriidae) from the medium ground finch (Geospiza fortis) from

the Galapagos Islands. J Parasitol 76(1):30–32

Mcquistion TE, Wilson M (1988) Four new species of Isospora from the

small tree finch (Camarhynchus parvulus) from the Galapagos

Islands. J Protozool 35:98–99

Mcquistion TE, Wilson M (1989) Isospora geospizae, a new coccidian

parasite (Apicomplexa: Eimeriidae) from the small ground finch

(Geospiza fu liginosa) and the medium ground finch (Geospiza

fortis) from the Galapagos Islands. Syst Parasitol 14:141–144

Power ML, Richter C, Emery S, Hufschmid J, Gillings MR (2009)

Eimeria trichosuri: phylogenetic position of a marsupial coccidium,

based on 18S rDNA sequences. Exp Parasitol 122:165–168

Şaki CE, Özer E (2012) Isospora species (I. canaria, Isospora sp.) in

canaries (Serinus canarius, Linnaeus). Turk J Vet Anim Sci 36:197–

200

Schoener ER, Alley MR, Howe L, Castro I (2013) Coccidia species in

endemic and native New Zealand passerines. Parasitol Res 112:

2027–2036

Schrenzel MD, Maalouf GA, Gaffney PM, Tokarz D, Keener LL,

McClure D, Griffey S, McAloose D, Rideout BA (2005)

Molecular characterization of isosporoid coccidia (Isospora and

Atoxoplasma spp.) in passerine birds. J Parasitol 91:635–647

Tokiwa T, Kojima A, Sasaki S, Kubota R, Ike K (2017) Isospora lunaris

n. sp. (Apicomplexa: Eimeriidae) from the domestic Java sparrow in

Japan. Parasitol Int 66:100–105

Trachta e Silva EA, Literák I, Koudela B (2006) Three new species of

Isospora Schneider, 1881 (Apicomplexa: Eimeriidae) from the less-

er seed-finch, Oryzoborus angolensis (Passeriformes: Emberizidae)

from Brazil. Mem I Oswaldo Cruz 101(5):573–576

Yang R, Fenwick S, Potter A, Elliot A, Power M, Beveridge I, Ryan U

(2012) Molecular characterisation of Eimeria species in macropods.

Exp Parasitol 132:216–221

Yang R, Brice B, R yan U (2014) Isospora anthochaerae n. sp.

(Apicomplexa: Eimeriidae) from a red wattlebird (Anthochaera

carunculata) (Passeriformes: Meliphagidae) in Western Australia.

Exp Parasitol 140:1–7

Yang R, Brice B, Ryan U (2016) Morphological and molecular charac-

terization of Isospora neochmiae n. sp. in a captive-bred red-browed

finch (Neochmia temporalis) (Latham, 1802). Exp Parasitol 166:

181–188

Publisher’snoteSpringer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdic-

tional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Parasitol Res