Delineation of Potential Sites for Water Harvesting Structures

using Remote Sensing and GIS

M. Girish Kumar

.

A. K. Agarwal

.

Rameshwar Bali

Received: 12 February 2008 / Accepted: 20 September 2008

Keywords Rain water harvesting site suitability

.

Remote sensing

.

GIS

M.G. Kumar

1

.

A.K. Agarwal

2

.

R. Bali

1

()

1

Centre of Advance Study in Geology,

University of Lucknow,

Lucknow – 226007, India

2

Remote Sensing Application Centre,

U.P. Janakipuram,

Lucknow – 226021, India

e-mail: [email protected]

Abstract Availability of groundwater varies spatially

and temporally depending upon the terrain. The

scarcity of water affects the environmental and

developmental activities of an area. Construction of

small water harvesting structures across streams/

watersheds is gaining momentum in recent years. In

the present study, potential sites for construction of

rainwater harvesting structures in the Bakhar

watershed of Mirzapur District, Uttar Pradesh, India

have been identified by using remote sensing

and GIS techniques. Various thematic maps such

as Landuse/Landcover, geomorphology and

lineaments, etc. were prepared using remote sensing.

These layers along with geology and drainage were

integrated using GIS techniques to derive suitable

water harvesting sites. Each theme was assigned a

weightage depending on its influence on ground

water recharge (for example weightages 20,18,15,25,25

and 0 were assigned to geomorphology, landuse,

geology, lineament, drainage and road and villages

respectively). Each class or unit in the map was

assigned a knowledge based ranking of one to four

depending on its significance in storage and

transmittance of groundwater, and these values were

multiplied with layer weightage to form score. The

average score for excellent region is greater than 200,

for good 121 to 200, for moderate 81 to 121 and the

other polygon having value less than 80 (excluding

zero) were assigned to poor category. The final map

showing different categories of suitability sites for

water harvesting structures such as Check dams,

J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. (December 2008) 36:323–334

Photonirvachak

123

RESEARCH ARTICLE

324

J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. (December 2008) 36:323–334

Contour bunding, Recharge pits, Wells and Contour

trenching have been suggested.

Introduction

Water, one of the most essential resources in our

day-to-day life is depleting faster in rural as well as

urban areas mainly because of increase in

agricultural and domestic demands. In water

resources planning, ground water is attracting an

ever-increasing interest due to scarcity of good

quality sub-surface water and growing need of water

for domestic, agricultural, and industrial uses. In a

densely populated country like India, ground-water

resource is in high demand. Continuous failure of

monsoon, increasing demand and over exploitation

leads to depletion of ground-water level, which in

turn tends to increase both the investment and the

operational costs. This problem could be sorted out

to certain extent by artificially recharging the

potential aquifers. In hard rock terrains, availability

of groundwater is of limited extent. Occurrence of

groundwater in such rocks is essentially confined to

fractured and weathered horizons. Efficient

management and planning of groundwater in these

areas is of the utmost importance. Extensive hydro-

geological studies have been carried out by several

workers in delineating groundwater potential zones

in hard rock terrain (Agarwal et al., 1992; Rao et al.,

2001). For delineating the groundwater potential/

prospective zones, Geographical information system

(GIS) has been found to be an effective tool. In

recent years, use of satellite remote sensing data

along with GIS, topographical maps, collecteral

information and limited field checks, has made it

easier to establish the base line information on

groundwater prospective zones (Saraf and Jain,

1993; Krishnamurthy et al., 2000; Agarwal et al.,

2004). Most of the above studies were mainly carried

out to identify areas having groundwater potential,

but very little work has been done to identify zones

suitable for artificial recharge (Saraf and Choudhury,

1998; Agarwal et al., 2005). Like delineation of

groundwater potential/prospect zones, delineation of

potential sites for artificial recharge is also governed

by several factors such as geology, geomorphology,

lineaments, landuse/cover, roads map, village

location map, permeability, soil depth, drainage

intensity, soil texture, water holding capacity and

physiography. The overall methodology involves

extraction and generation of various thematic maps

either through satellite images or through existing

records and field survey maps. The next step deals

with classification of all these parameters into

‘suitable’ classes and assignment of ‘suitable’ ranks

to these classes, weights to the parameters, and

finally integration of all the ranked and weighed

parameters in a GIS environment. Subsequently, the

area is classified into poor, moderate, good and

excellent sites suitable for the rainwater harvesting.

Study area

The present studies have been carried out in

Bakhar watershed lying between Latitude 24

0

45' to

24

0

56' N and Longitude 82

0

29' to 82

0

56' E falling in

the Survey of India (SOI) Topographical sheet No.

63 L/9 and 63 L/13 (Fig. 1), with an area of around

560 km

2

. The average annual rainfall with in the

watershed is 747.52 mm and the maximum average

annual temperature is 32.1

0

C (Anonymous, 2003).

The topography of the study area, in general, is

gently undulating dissected plateau. The Quaternary

sediments are deposited over the sandstones. The

present drainage network of the Bakhar watershed

has been delineated using satellite data. In the

Sandstone terrain, the drainage pattern is dendritic

and in the Quaternary sediments region the

drainages are sub-dendritic to sub-parallel. It is

observed that in the Bakhar watershed, new

drainages have come up and some streams have

changed their course in the northern (Gopalpur) and

325

J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. (December 2008) 36:323–334

eastern (Rajgarh) side. The satellite data has also

revealed that some drainage lines have disappeared

and new tanks (surface water bodies) have come up

in the recent times. Field visits to these places

confirm the same. Roads and settlement layers have

been derived from Land Record Department, District

Mirzapur and were updated using the satellite

images.

photographs and digitally enhanced products of the

Indian Remote Sensing Satellite (IRS, LISS-III)

sensor. Arcview 8 software package was used for

creation of digital database, data integration and

analysis. All thematic maps were digitized (in

continuous mode in the vector format and the

digitized values were then edited). Different

categories of polygons in the thematic maps were

Fig. 1

Methodology

Basic technical guidelines provided by the

Integrated Mission for Sustainable Development

(IMSD) and Indian National Committee on

Hydrology (INCOH) have been adopted for selecting

sites for rainwater harvesting structures. The

thematic maps depicting the geomorphology,

landuse/landcover, road, drainage and lineaments

were prepared using 1:50,000 scale geocoded

labelled separately. The suitable weights were

assigned to each thematic feature after considering

their characteristics upon their influence over

recharge. Knowledge based weight assignment was

carried out for each features and they were

integrated and analysed by using the weighted

aggregation method (ESRI, 1988). The different units

in each theme were assigned ranking from 1 to 4 on

the basis of their significance with reference to their

site selection for installing rainwater-harvesting

326

J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. (December 2008) 36:323–334

structures. In this ranking, ‘0’ denotes the restricted

area (e.g. forest region) and no structure is proposed

for that area, 1 denotes poorly favourable zones, 2

denotes moderately favourable, 3 denotes highly

favourable and 4 denotes excellent zone for site

selection for rain water harvesting structures. The

final score of a theme is equal to the product of the

rank and weightage. From the composite layer, the

delineation of site suitability analysis was made by

grouping the polygons into different prospect zones

i.e. excellent, good, moderate, poor and not suitable.

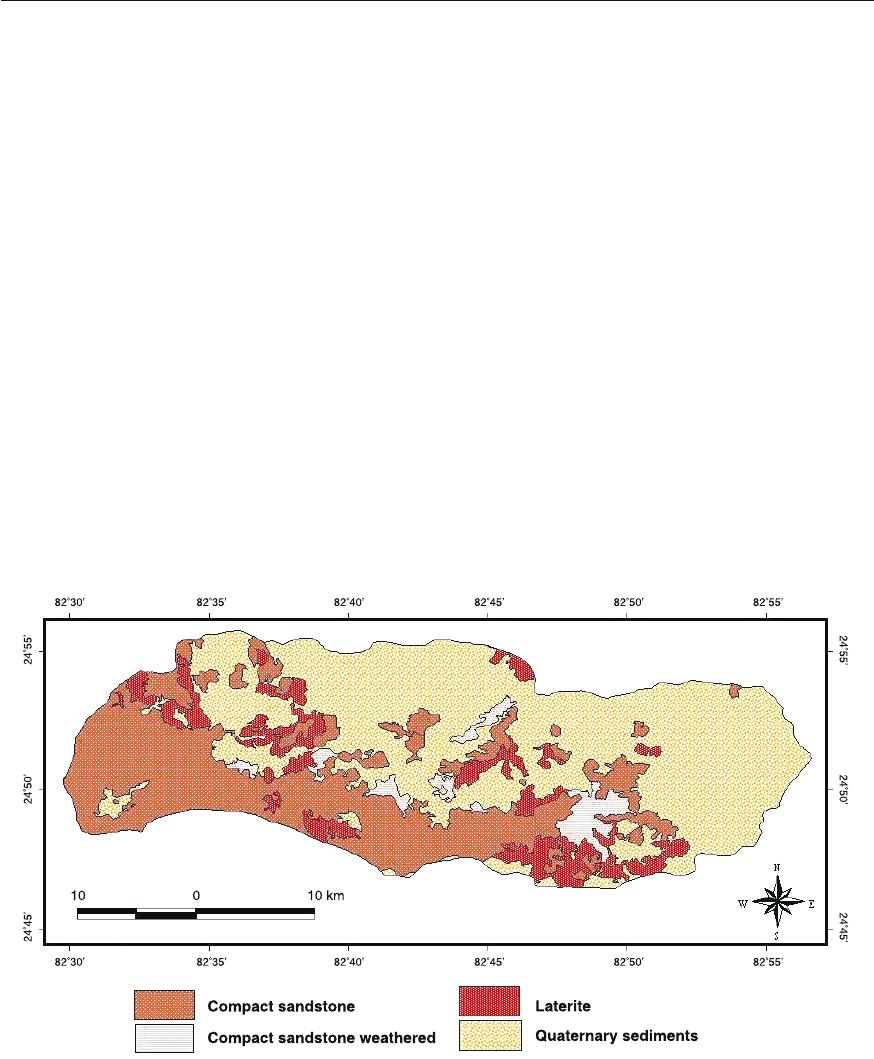

Geological set-up

It is a well-established fact that geological set-up

of an area plays a vital role in the distribution and

occurrence of groundwater (Krishnamurthy and

Srinivas, 1995). The geological set-up and

stratigraphy of the Vindhyan Super group in the Son

valley, Central India was earlier proposed by Auden

(1933) and later on revised by Prakash and Dalela

(1982). The Bakhar watershed is dominated by

compact sandstones of Kaimur series. At some

places, especially in the northern and eastern parts

of the watershed, it is overlain by Quaternary

alluvium (Fig. 2).

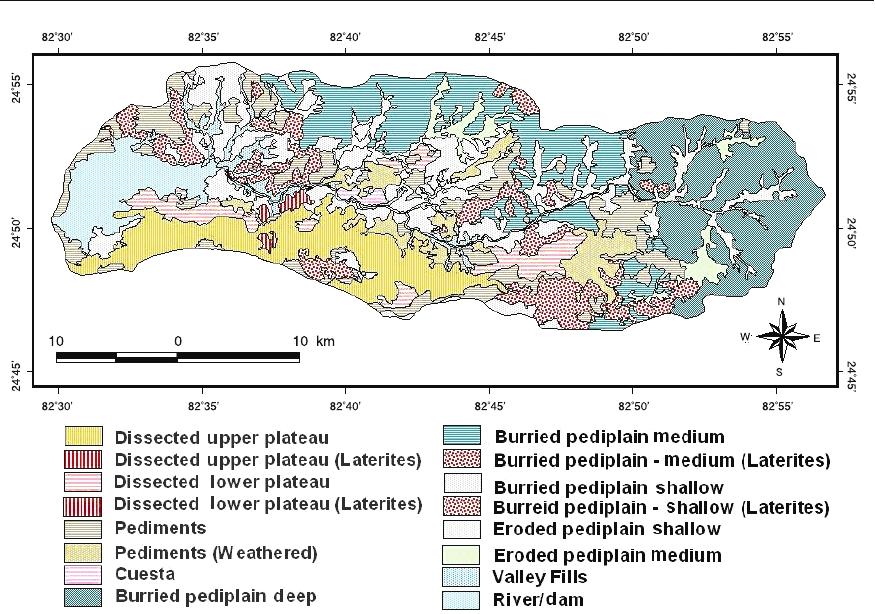

Geomorphological set-up

Geomorphology of an area is one of the most

important features in evaluating the groundwater

potential and prospect. The geomorphology as such

controls the subsurface movement of groundwater.

Considering the importance, different geomor-

phological features are mapped using the IRS

satellite imagery (Fig. 3). Various geomorphic

classes/units identified as per the guidelines laid

down by National Remote Sensing Centre,

Hyderabad (NRSC Technical guidelines, 1995). The

data has been duly validated during field visits. The

major landforms are as follows:

Fig. 2

327

J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. (December 2008) 36:323–334

Dissected plateaus

These units are highly fractured and weathered and

show the formation of laterites. They show light

reddish tone and cover the southern part of the

watershed.

Pediments

Generally these units have low permeability and

infiltration rate and are noticed around the dissected

plateau region and drainage divide area of the

watershed. These units show patches of light

brownish tone with irregular shape and size.

Buried pediplains

Buried pediplains are formed due to coalescence of

buried pediments having thick overburden of

weathered materials. These landforms are charac-

terized by high porosity, permeability and infiltration

rate and as such the groundwater prospects of the

buried pediplain are good. In the FCC these units

show dark blue to light blue tone and most of the

eastern and northern part of the watershed.

Valley fills

Valley fills are mostly structurally controlled and the

materials are mainly sheet wash from the plateau area

Fig. 3

328

J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. (December 2008) 36:323–334

and pediplains. Valley fills consist of both alluvial

and colluvial materials and are mostly identified

along the various streams of the watershed. These

are identified by characteristic bright spectral

signatures in the false colour composite of band 2,

3, 4. This geomorphic unit acts as good prospective

zone for groundwater development.

Eroded pediplain

This unit is seen along the streams of high and low

lying areas. These landforms give a bright red tone

in satellite data due to the presence of vegetation.

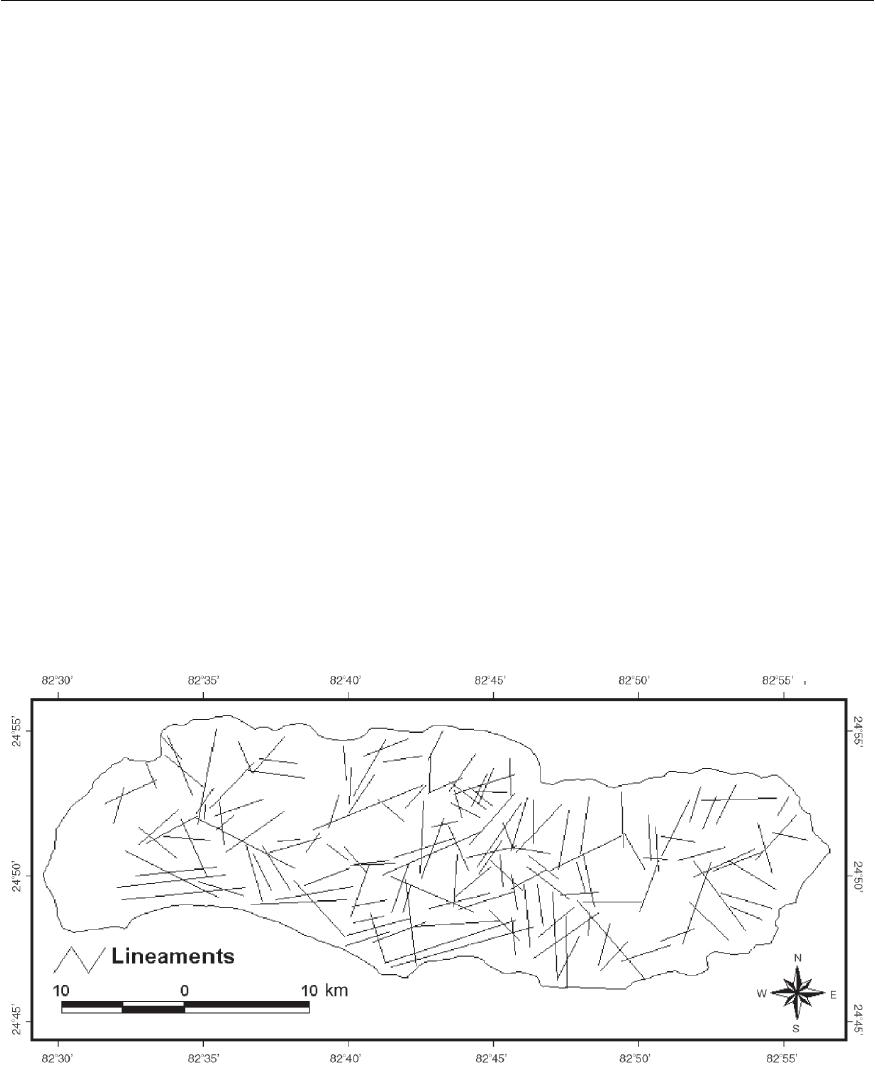

Lineament distribution

A lineament is defined as a large scale linear

structural feature. Such features may represent deep

seated faults, master fractures and joints sets,

drainage lines and boundary lines of different rock

formations. Lineaments provide the pathways for

groundwater movement and are hydrogeologically

very important (Sankar, 2002). Lineaments are

important in rocks where secondary permeability,

porosity and intergranular characteristics together

influence groundwater movements. The lineament

intersection areas are considered as good

groundwater potential zones. The combination of

fractures and topographically low grounds can also

serve as the best aquifer horizons (Rao, 1992).

Lineaments have been identified on images through

visual interpretation by comparing spatial variation

in tone, colour, texture, association, etc. (Fig. 4).

25 m area on either side of lineaments and

intersections of lineaments are considered to be

favourable for accumulation of groundwater.

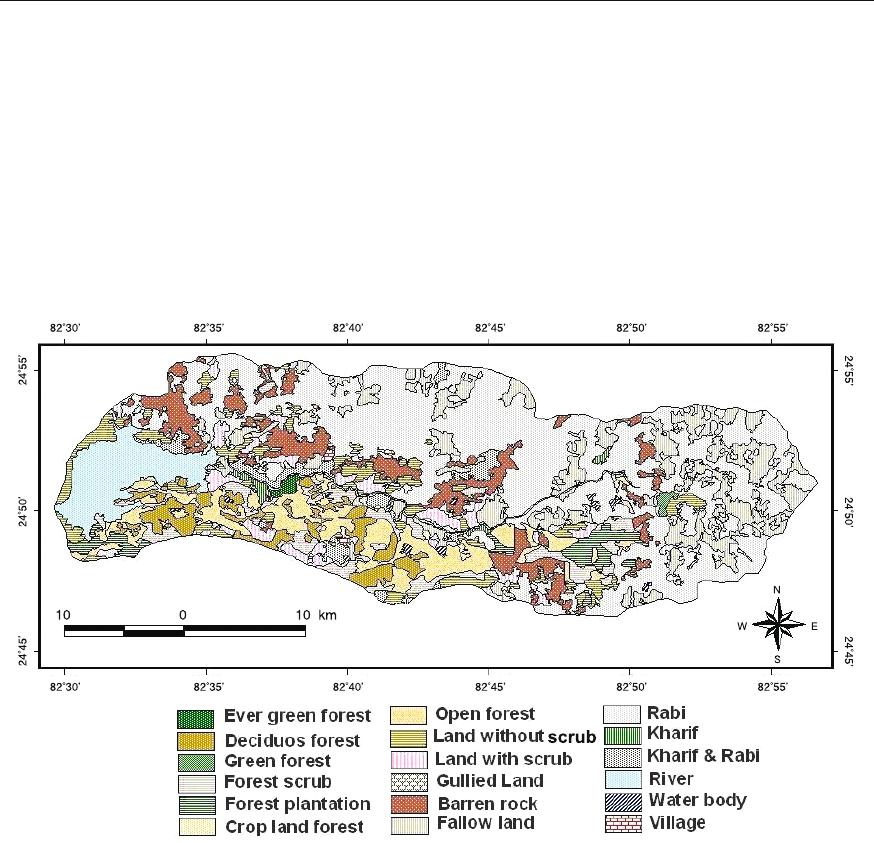

Land use / Land cover

The major landuse pattern include cropland, fallow

land, forest area, forest plantations, Barren rocky

area, land with scrubs and without scrubs. Cropland

includes land for growing the Rabi and Kharif crops

and have been identified by the light medium red

tone, fine/medium texture varying in size, often

rectangular in shape. These are excellent site for the

groundwater exploration. The forest and forest

Fig. 4

329

J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. (December 2008) 36:323–334

plantation gives light reddish brown tone with white

patches and fine to medium texture with irregular

shape and varying size. Although, these areas have

good ground water prospects, these have been

purposefully categorized as poor, keeping in mind

that these areas are generally restricted and are not

permitted for any ground water exploitation activity.

Lands without scrub have been rated lower than land

with scrub for recharge, since vegetation cover

promotes infiltration (Fig. 5).

structures depends on various factors, which can be

integrated by GIS techniques (Novaline et al., 1993).

To assess the groundwater prospect in an area, all

the different polygons in the thematic maps were

labelled separately. Knowledge based weightages are

assigned to each thematic features after considering

their importance with respect to groundwater. All the

thematic maps are integrated in GIS environment and

the polygons have been regrouped into different

classess.

Fig. 5

GIS Analysis

Check dams, contour bunding, recharge pits and

wells and contour trenching provide a good measure

of rainwater harvesting structures in the hard rock

terrains by arresting run-off and increasing the

surface area of infiltration. Suitability of these

Weight Assignment

Thematic layers viz, geomorphology, geology,

landuse, lineaments buffer zone, drainage, road and

village location map have been considered for

site suitability analysis. Based on the available

knowledge on the role of each of these parameters

330

J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. (December 2008) 36:323–334

in controlling the occurrence, storage and

distribution of groundwater, weightages of 20, 15, 18,

25, 25 and 0 were assigned for geomorphology,

geology, landuse, lineament, drainage and roads and

villages respectively. Again each of these layers has

further been classified into different classes. Each of

the classes, based on its ability to facilitate water

infiltration has been given ranks from 1 to 4. Finally,

scores have been calculated as the product of

the weightage and rank e.g. under the class geo-

morphology (wt. 20), valley fills have been assigned

the rank 4. The final score of 80 has been calculated

by the multiplication of the rank and weightage of

the class (Table 1).

The thematic layers were integrated with one

another through GIS using the weighted aggregation

method. The following order of sequence was

adopted to derive the final integrated map.

Table 1 Rank, weightage and scores for the various themes with respect to site suitability analysis

Geomorphic Unit Weightage - 20 Landuse Unit Weightage - 18

Class Rank Score Class Rank Score

Valley fills 4 80 Kharif 4 72

Eroded pediplains shallow 4 80 Rabi 3 57

Eroded pediplains Medium 3 60 Kharif + Rabi 4 72

Burried pediplain – Deep 4 80 Fallow land 3 57

Burried pediplain – Moderate 3 60 Land with scrub 2 36

Burried pediplain – Shallow 2 40 Land without scrub 2 36

Pediments 2 40 Barren rocky 1 18

Pediments (W) 3 60 Dense evergreen forest 0 0

Dissected upper plateau - Laterite 1 20 Deciduous forest 0 0

Dissected lower plateau - Laterite 1 20 Open forest 0 0

Dissected upper plateau 1 20 Scrub forest 0 0

Dissected lower plateau 1 20 Open forest 0 0

Geology Unit Weightage - 15 Crop land forest 0 0

Class Rank Score Guilled land 1 18

Compact sandstone 1 15 Water bodies 0 0

Compact sandstone (Weathered) 2 30 Settlements 0 0

Laterite 2 30 Reservoir/river 0 0

Alluvium 4 60 Settlements 0 0

Drainage Unit Weightage - 25

Class Rank Score

Lineaments Unit Weightage – 25 Drainage (50m buffer) 4 100

Class Rank Score Road & Village Unit Weightage - 0

Lineament (50 m buffer) 4 100 Class Rank Score

Road & Village (50m buffer) 0 0

331

J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. (December 2008) 36:323–334

Geology (R1) + Geomorphology (R2) = S1

S1 + Landuse/landcover (R3) = S2

S2 + Lineament of 50m buffer (R5) = S3

S3 + Drainage of 50 m buffer (R4) = S4

S4 x Road and village layer (R6) = S5

In the first step, geology (R1) and geomorphology

(R2) layers were integrated by choosing the union

option. The integrated layer (S1), comprises 68

polygons of the geology layer and 215 polygons of

the geomorphology layer and after union it resulted

in 674 polygons. Adding these two layers, derived

the weight of each polygon in the integrated layer

(S1). The polygons in S1 have a maximum value of

140 and minimum of 35. In the next step, the S1 layer

containing 674 polygons was intersected with the

land use layer (R3), which had 339 polygons. In this

step, the integrated layer S2 (9209 polygons) was

generated by adding lithology, geomorphology and

landuse layers. These polygons have a maximum

weight of 212 and minimum of 35. The S2 layer was

integrated with polygons of the lineament buffer zone

(R4). In this integrated layer (S3), (13458 polygons

were generated) having a maximum value of 312 and

minimum of 35.

Layer R5 involving polygons made around the

drainage (buffer zone) was integrated with layer S3

by the union option. In this layer (S4) there are 24236

polygons which have a maximum value 412 and

minimum of 35. The village and road layers (R6)

having zero weightage were integrated with S4, using

multiplication option. The polygons in the integrated

layer (S5) had retained the same values of S4 except

the null value of road and village. The polygons in

the integrated layer (S5) contain the composite detail

of all the thematic layers together numerically having

maximum weight of 412 and minimum weight of zero.

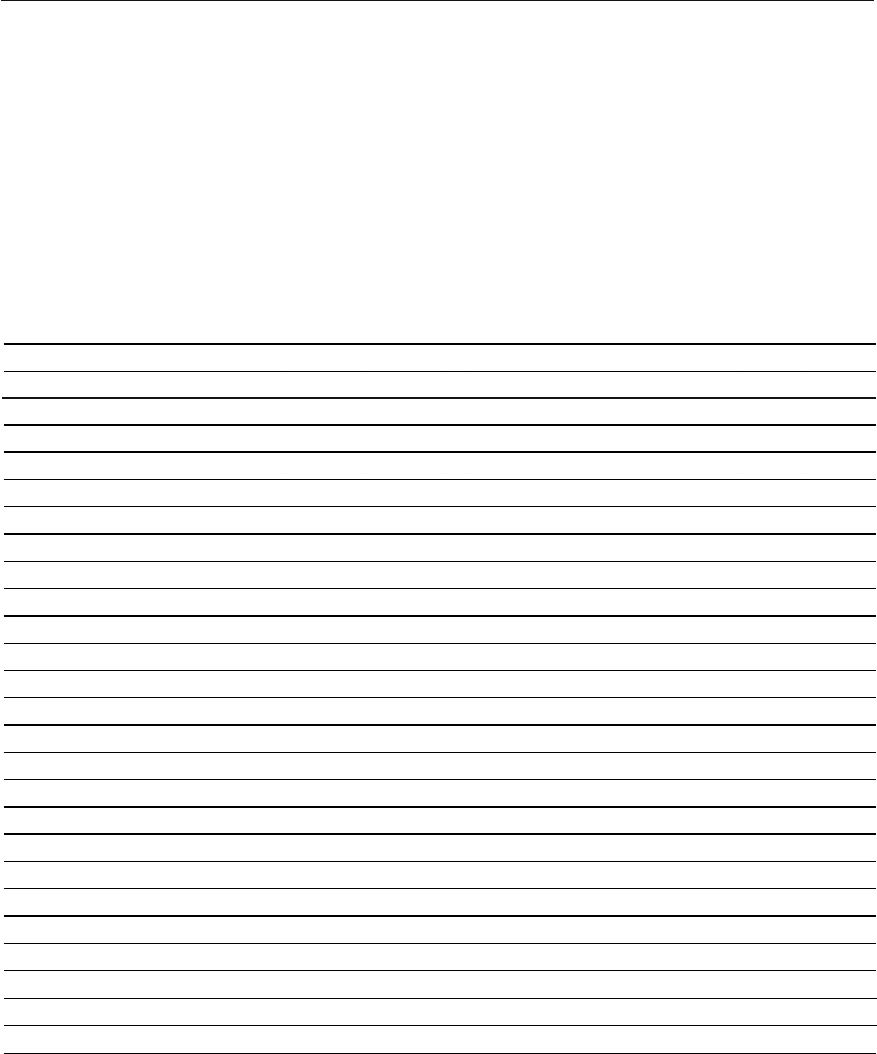

Results and discussion

Grouping of polygons of high ranks of all the

thematic layers has helped in delineating the sites

that are excellent for construction of water

harvesting structures. Those polygons, which

have weight greater than 200 in the final integrated

layer have been, classified as excellent sites for

rainwater harvesting. The polygons classified as

good category have the weights between 121 and

200 and as of Moderate category have the weights

between 81 and 120. All other polygons that have

weight less than 80 (excluding zero) were grouped

as a poor category. Polygons having zero weights

have been separated out (not suitable category) as

these have been classified as reserve forests, roads

and villages. Thematic map (Fig. 6) showing the sites

suitable for construction of rainwater harvesting

structures suggests that the drainage area and the

eastern part of the study area are most suitable for

construction of rainwater harvesting structures.

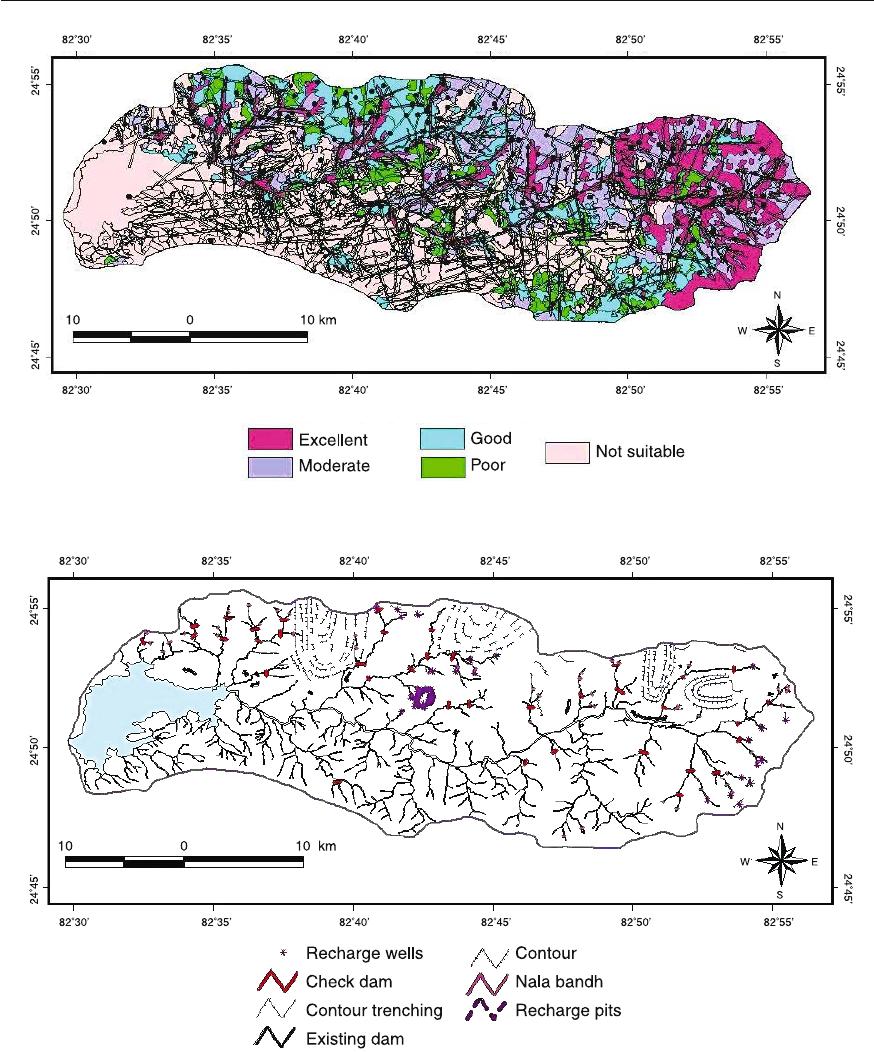

Proposed rain water harvesting structures for

Bakhar watershed

The site suitability analysis (Fig. 6) has helped in

locating the suitable sites for the water harvesting

structures. Based on the above classification as well

as depth to water table map and terrain conditions,

a map suggesting the type of structures to be built

at various locations has been prepared (Fig. 7). The

proposed structures are check dams, contour

bundings, contour trenchings, nala bandhs, recharge

pits and wells. The numbers of structures proposed

in the study area are given (Table 2). The key factors

for selecting a particular structure at a given site are

as follows:

Check dam

(i) The check dam is essentially on the drainage

coarse, that may be situated on either 1

st

or 2

nd

order

of drainage; (ii) The preference for this structure is

given where drainage is narrow and straight; (iii) The

structure of check dam should be made so as to

regulate the water during monsoon and non

332

J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. (December 2008) 36:323–334

Fig. 6

Fig. 7