Vol.:(0123456789)

SN Computer Science (2021) 2:4

https://doi.org/10.1007/s42979-020-00393-8

SN Computer Science

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Scientic Collaboration inaMultidisciplinary Organization Revealed

byNetwork Science

IvanBergier

1

· PatríciaMenezesSantos

2

· AndreiaHansenOster

3

Received: 16 October 2020 / Accepted: 5 November 2020

© Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd 2020

Abstract

Multidisciplinary scientific organizations have sought to face the challenges of digital transformation through new govern-

ance models that optimize network collaboration and innovation. We studied the collaboration network from the long-term

coauthoring system of a Brazilian multidisciplinary organization (Embrapa). The study shows that nodes degree distribution

of the network is scale free and degree correlation analysis suggests a disassortative regime from competition and minimal but

sufficient control that emerges as a hub-and-spoke pattern. The jobs of controller and researcher are twice as many occupied

by males, except for the jobs of analyst, who act like network gatekeeper. With the largest number of individuals in product

units, the southern region of the country is more likely to form clusters. Alternatively, hubs in thematic and ecoregional

units in the Midwest have greater gravitational attraction, positioning themselves in the inner core of the giant component.

The optimization of innovation by the organization should combine greater individual autonomy through improved human

capital, with a universal labeling of units as, for instance, centers of innovation.

Keywords Business intelligence· Innovation process· Hub-and-spoke· Organization control

Introduction

Studies of scientific collaboration have fertile grounds on the

principles of network science [1, 2]. Emerging from statisti-

cal physics and the science of complexity [1–4], network

science is a transversal discipline providing the theoretical

bases for studying and modeling real systems with empiri-

cal data [5]. Vertices (nodes) and links (edges) constitute a

network, in which nodes with many edges have high-degree

k. The distribution of values of k is important because the

structure or the anatomy of a network reflects its internal

dynamics of evolution and affects important functions like

the dissemination of information/disinformation and the

resistance to failure [1, 3, 6].

Barabási and Albert [7] have shown that heavy-tailed

degree distributions p (k) are emergent properties of sto-

chastic growth models. New nodes continuously attach

themselves to existing network nodes with probability

proportional to k of the target node [8]. Observed in many

empirical data and in a variety of systems, the phenomenon

was coined as preferential attachment [9].

The heavy-tailed degree distribution is described by a

power law function

p

(

k

)

∼ k

−𝛾

, with or without exponen-

tial cutoffs [10], where a giant component (many connected

nodes) exists for 2 ≤ γ < 3.47 [5, 11]. The fast decaying p (k)

with the increase in k indicates that a very small number

of high-degree nodes coexists with a very large amount of

low-degree nodes. The former are called hubs, which affect

both the topology and the evolution of the system. Moreo-

ver, the heavy-tailed distribution is scale free, i.e., the first

moment <k> has less relevance, since the second moment

diverges as the total number of nodes n and k increases.

Above all, in scale-free networks with hubs and random

clustering, the average path length <l> between nodes is

reduced and proportional to n [5], which agrees with the

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this

article (https ://doi.org/10.1007/s4297 9-020-00393 -8) contains

supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

* Ivan Bergier

ivan.ber[email protected]

1

Embrapa Pantanal, Brazilian Agricultural Research

Corporation, Corumbá, MS, Brazil

2

Embrapa Pecuária Sudeste, Brazilian Agricultural Research

Corporation, SãoCarlos, SP, Brazil

3

Embrapa Uva e Vinho, Brazilian Agricultural Research

Corporation, BentoGonçalves, RS, Brazil

SN Computer Science (2021) 2:4 4 Page 2 of 11

SN Computer Science

concept of highly connected communities of small world

networks [6].

Scientific collaboration is an undirected social network,

where the nodes are scientists and the edges denote co-

authorship. Coauthoring systems have been considered

reliable patterns of social network dynamics, from which

graph, clustering and centrality measures are useful to reveal

hidden facets of scientific development in many fields of

research [12, 13]. In turn, big data from metadata derived of

digital publication databases are useful sources of informa-

tion for business intelligence [14, 15]. In addition, network

science can be valuable in the search of topological arrange-

ments that optimize innovation internally and among small

and large multidisciplinary organizations [16, 17], where

preferential attachment is affected by hierarchy-energy

dynamics [18].

By rule, a coauthoring topology indicates the type of

association between nodes in a scientific network. For

example, the co-authorship clustering was found higher in

physics rather than mathematics and biology communities

[13]. Furthermore, the degree correlation

k

nn

(

k

)

∼ k

𝜇

, i.e.,

the tendency of nodes to connect to other nodes with simi-

lar (assortative, µ > 0) or dissimilar (disassortative, µ < 0)

degrees, has been found assortative in many scientific col-

laboration networks [2, 13]. On the other hand, it has been

shown that scale-free networks can be controlled by a finite

subset of the network, called the dominant set Γ (γ, µ, <k>)

for which Γ ≤ n/2 [19, 20].

This article explores the big data of preferential scientific

collaboration in Embrapa (Brazilian Agricultural Research

Corporation), a multidisciplinary government research

organization responsible for the Brazilian ‘green revolution’

in rural areas. In the last 47years, Embrapa played an impor-

tant role in changing the Brazilian status of food importer to

a global player in sustainable food markets [21, 22], placing

the country among the main global traders responsible for

food security and sustainability [23].

Embrapa infrastructure of research, development and

innovation (RD&I) ramifies into the inner Brazilian regions

as departments or decentralized research units whose des-

ignations have been associated to national products of large

importance (Product), edaphic–climatic conditions or biome

(Ecoregional) or other exceptional knowledge (Thematic)

[24–26]. In addition to administrative and assistance work,

the main occupations are Analysts engaged in lab, field or

administrative support, and Researchers committed to a

shared RD&I agenda.

The technological disruptions of information and commu-

nication, the escalation of startups and the torrent of social

(web) interactions have mutually challenged Embrapa. The

need to improve efficiency is highlighted by redesigning

communication, partnerships and funding sources. Among

the responses to these challenges, one can underline: (1) the

numeric reduction of RD&I projects in strategic portfolios

[27], (2) interfaces reorganization to improve open innova-

tion; and (3) the adoption of TRL—Technological Readiness

Levels [28] to strengthen collaboration with the private sec-

tors [29, 30].

In summary, the motivation of the present work is to

decipher the unknown preferred scientific collaboration

in the multidisciplinary Embrapa through network science

[5, 31, 32], assuming that the network topology reflects a

canonical pattern of the organization’s social dynamics [1,

6]. Embrapa, in its complexity of research areas, and conse-

quently the degree of researchers (different areas of knowl-

edge), could help explain different behaviors of co-author-

ship and collaboration [10, 13, 33]. For that goal, this paper

explores network science principles and provides informa-

tion about the big data compilation in Sect.2. Results are

depicted in Sect.3, subdivided into statistical (3.1 and 3.2)

and graph (3.3) analyses. Related works and conclusions are

presented in Sects.4 and 5, respectively.

Materials andMethods

There are five essential characteristics to be explored with

network science: (1) structural complexity, (2) connectiv-

ity and node diversity, (3) network evolution, (4) dynami-

cal complexity and (5) meta-complication [1]. The present

work focuses on items (1) and (2) associated with the current

topological state of the network.

Dataset

The co-authorship dataset was compiled from Embrapa’s

publication repository in the Agricultural Research Database

(BDPA) under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license. The data mining

consisted of organizing a list of nodes with the attributes:

name (<publication_name> or <proxy_name>), gender

(<female> or <male>), unit type (<product> , <ecore-

gional> or <thematic>), location (<south> , <mid-

west> , <northeast> , <southeast> and <north>), and job

position (<analyst> , <researcher> , <controller> or external

collaborator <extcollab>).

The alphabetic list of n nodes with attributes allowed

searching each of them through name attribute in BDPA.

Node queries were carried out from December 2019 to

March 2020. It were recorded for each node the values

of <publication_name> (surname and initials) of the ten

closest nodes (preferred or most frequent coauthors), includ-

ing the node itself. In this way, a maximum of 10 <publica-

tion_name> values were recorded, of which the searched

node is the first element of an array i with j closest coauthor

nodes represented by a

i,j

. Iteratively, an adjacency matrix

m

n,j

with 1 ≤ j ≤ 10 undirected coauthoring nodes was

SN Computer Science (2021) 2:4

Page 3 of 11 4

SN Computer Science

produced. In any case, whenever <publication_name> of the

a

i,1

node was unattainable, her/his surname and initials in the

alphabetic list were assumed as <proxy_name>.

Gephi 0.9.2 [34] and Microsoft Excel

®

supported the

numbering or codification of nodes and edges of the adja-

cency matrix m

n,j

. Initially, m

n,j

was imported into Gephi to

create and export a CSV data file with a list of paired edges

of attributes <publication_name> or <proxy_name> when

needed.

As the codes and attributes of nodes a

i,1

are known, it

was possible to compare them with all other edge nodes

in Excel to produce a new list of paired edges coded by

nodes. For that purpose, a conditional matrix was created

to code a

i,j

= a

i,1

if <publication_name> (or <proxy_name>)

attribute was the same. In addition, the procedure was use-

ful for identifying and reviewing <proxy_name> attributes

because some nodes do not adopt surnames like <publica-

tion_name> or because BDPA provided the attribute a

i,j

with

j > 1. Finally, the remaining coded nodes without any other

attribute information, associated with external collaborators

(non-employees), were assigned as <extcollab>.

Encoded nodes with attributes and edges in CSV data

files were opened in Gephi 0.9.2 and explored via network

science (see below). The links were imported by averag-

ing parallel edges. Preliminary drawing, sizing and coloring

according to partitions (node attributes, centralities and clus-

tering indexes) were useful to rectify the big data, ensuring

consistency and quality.

Network Graphs andMeasures (Theory

andCalculation)

Graph Layout

Gephi 0.9.2 [34] was used to draw networks, identify com-

munities with modularity class [35], and to calculate cluster-

ing coefficients [6] and other measures of centrality [31, 32,

36]. The default layout Yifan Hu [37] was chosen to expand

the initial randomly distributed nodes in the overview graph

window. Subsequently, ForceAtlas2 algorithm [38] was

adjusted to scale 3 with approximate repulsion and prevent-

ing overlapping of nodes. The measures of centrality of the

network were then computed and nodes were size-ranked by

betweenness centrality [36], ranging from 25 to 250 with an

exponential spline function to facilitate the visualization of

nodes and edges. Then, the attributes of nodes were explored

through color pallets.

Degree Correlation, Centrality andClustering Measures

The measures of centrality compute the importance of nodes

in a network. To study the co-authorship network, three

measures of centrality were evaluated:

•

Degree (k): it measures the number of edges or links con-

nected to a node. The more edges the greater the node

degree, and highly connected nodes are known as hubs

[31].

•

Betweenness: it is positively correlated with k, corre-

sponding to the frequency at which a node appears in the

shortest paths between all pairs of nodes in a network.

Higher values confer hub skills [31, 32].

•

Closeness: it is the mean of the shortest path length from

one node to all other nodes. A low value suggests that the

node is closely connected to every other node; therefore,

it is considered a gatekeeper (cluster connector) in a net-

work [31, 32].

The degree correlation captures the relationship between

each node degree k with the averaged degree k

nn

(k) of edged

nodes (immediate neighbors). The degree correlation func-

tion is

k

nn

(

k

)

∼ k

𝜇

where µ = 0 relates to a neutral regime,

µ < 0 to a disassortative regime (low-degree nodes connect

to large-degree nodes and vice versa) and µ > 0 to an assor-

tative regime (nodes tend to connect to other nodes with

an equivalent degree) [5]. The degree correlation was cal-

culated for the co-authorship network by implementing a

conditional matrix in an Excel datasheet to address k values

for coded and paired edges. Then, k

nn

(k) function could be

obtained by calculating the average values of k for all undi-

rected (in and out) nodes.

In addition, clustering coefficient and modularity class

have been also evaluated:

•

Clustering: it is a measure of the degree to which nodes

in a graph tend to group together [6].

•

Modularity class: it is a clustering algorithm that detect

communities of nodes [35].

The distributions of network measures were studied with

nonparametric (median-oriented) tests and boxplots grouped

by attributes with the aid of Past 4.02 software (https ://

www.nhm.uio.no/engli sh/resea rch/infra struc ture/past/).

The nonparametric statistical analyses are available in the

Appendices.

Results

Degree Distribution andCorrelation

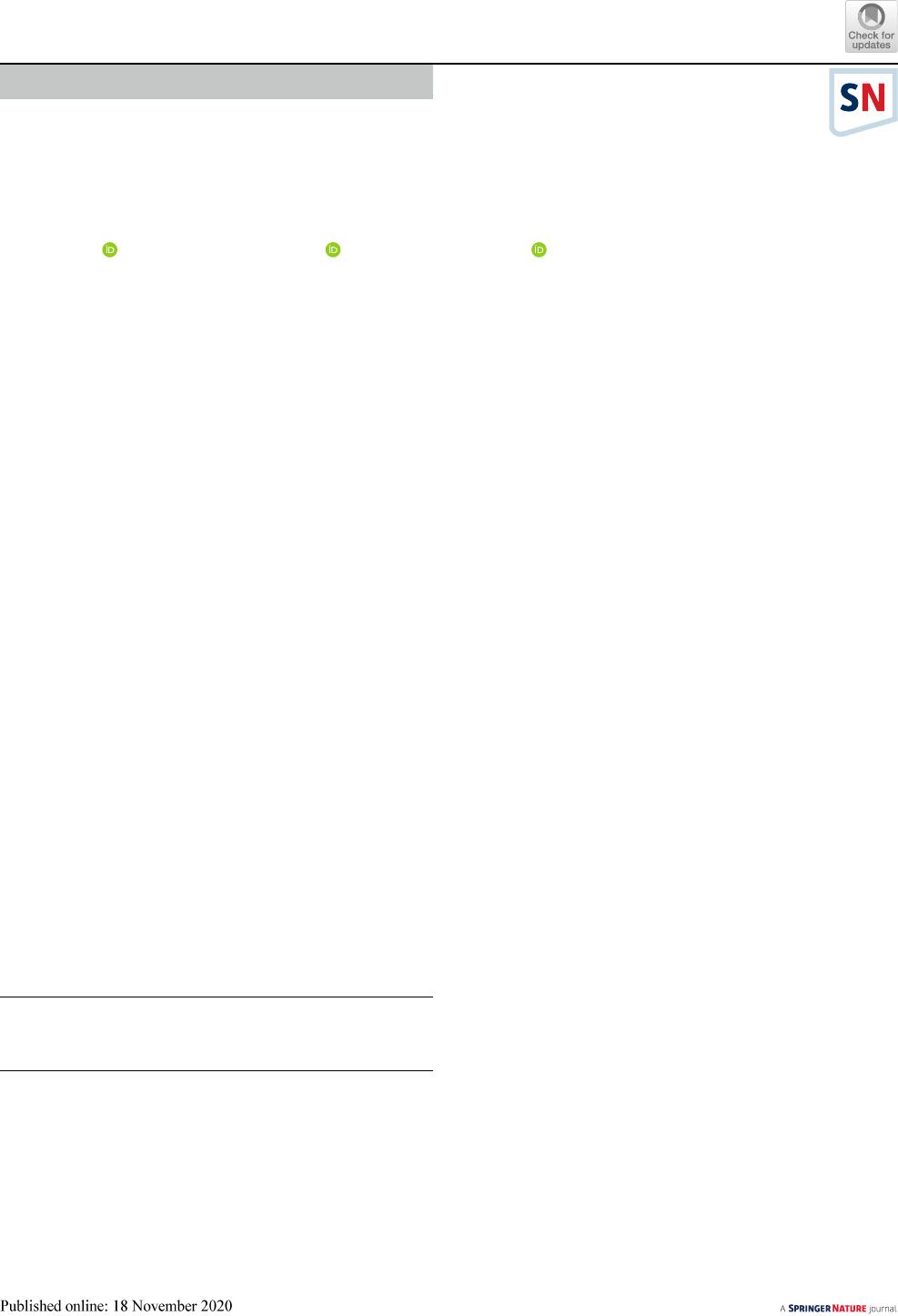

The entire network with 9207 undirected nodes and 15,696

edges showed a degree distribution ranging from 0 ≤ k ≤ 409,

with mean network degree <k> = 3.41, diameter 12, null

density and average path length <l> = 5.466. The normal-

ized log-binned probability distribution p (k) is shown in

Fig.1.

SN Computer Science (2021) 2:4 4 Page 4 of 11

SN Computer Science

Despite a few internal and many external collaborators

for whom k = 1 (6923 nodes), the frequency of nodes with

k < 9 is very small (318), indicating that most nodes has at

least nine preferential coauthors. Nodes with k ≥ 9 (1777) are

those with increasing co-authorship of scientific documents.

The distribution p (k) indicates a free scaling network with

large hubs resulting from preferential attachment [9].

For scientific collaboration, a p (k) distribution is usually

scale free and decays with an exponent γ > 3, which indicate

a random regime indistinguishable from a random network

[5]. For the Embrapa dataset, bootstrap interval estimation

reaches 1.6613 ≤ γ ≤ 2.273 (Fig.1), suggesting that the net-

work results from a nonrandom scale-free regime associated

with the interval 2 ≤ γ < 3.

In particular, the log-binned regression gives γ ~ 2, indi-

cating an anomalous scale-free regime that induces a hub-

and-spoke (centralized) configuration [5], where most nodes

are closer to each other (constant path length l) because

almost all of them connect to a common central hub. Since

the largest hub (k

max

) is given by

k

max

= k

min

× n

(

𝛾 −1

)

−1

, then

the number of hubs increases linearly with n in that anoma-

lous scale-free case [5]. In brief, Fig.1 illustrates that, over

the organization timespan (currently 47years), only a very

small fraction of nodes gained much more connections (very

large hubs) than other nodes in the scientific collaboration

network of Embrapa.

Another interesting property of networks is given by the

degree correlation function

k

nn

(

k

)

∼ k

𝜇

. The exponent µ

is associated with the modus operandi of interconnection

between nodes. If the nodes connect randomly, then µ = 0.

In cases where nodes with similar values of k connect, the

degree correlation is assortative and µ > 0. In contrast, when

hubs preferentially connect to low-degree nodes (tending to

a radial topology with a centered hub), then µ < 0 and the

degree correlation is disassortative.

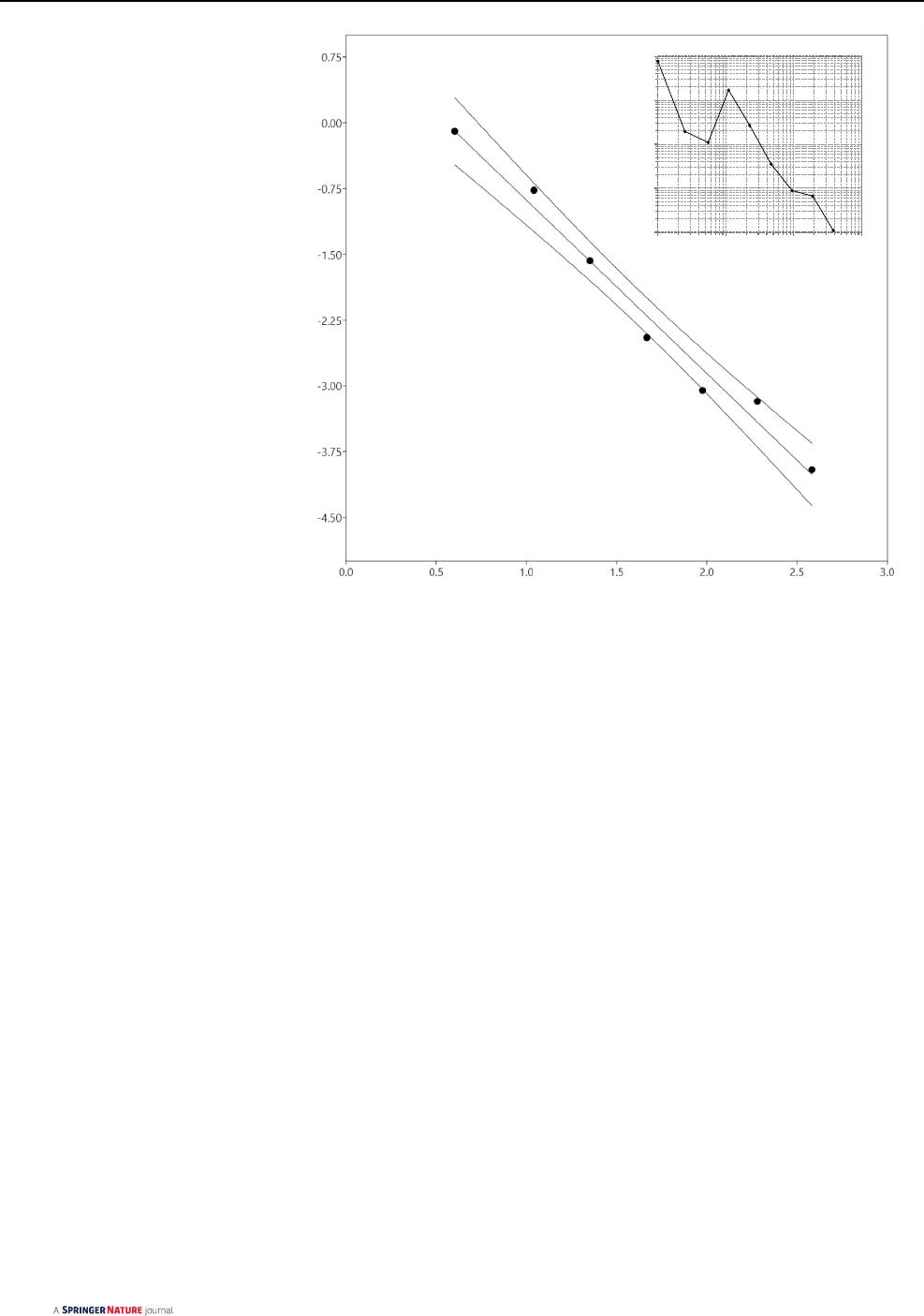

Figure2 presents the plot

k

nn

(

k

)

∼ k

𝜇

for the coauthor-

ing network. A disassortative regime is expected theoreti-

cally for the anomalous scale-free regime γ ~ 2. Accordingly,

statistical regressions and bootstrap of the empirical data

provide µ ≤ 0 (Fig.2).

As the network is a product of the evolving dynamics of

preferential attachment, then the hub-and-spoke radial pat-

tern of co-authorship emerges as a response of long lasting

internal organizational dynamics, in which some nodes have

better competitive fitness (characteristic individual features)

to gain more edges than others nodes [5].

Nonparametric Statistical Analyses

Measurements of network centralities (normalized

betweenness, closeness and degree), modularity and clus-

tering might be also useful to unveil internal dynamics

Fig. 1 Log-binned prob-

ability distribution

p

(

k

)

∼ k

−𝛾

with γ = 1.9768 ± 0.1215

(r

2

= 0.98146, p = 1.5993 × 10

–5

)

and 1.6613 ≤ γ ≤ 2.273 in

95% bootstrapped confidence

intervals with 1999 iterations.

The 189 nodes for which

k = 0 were dismissed, and the

frequencies of the log-bins

centered in k = 1, 2.5 and 5.5

were averaged as <k> = 4.

For k ≥ 10, regression reaches

γ = 1.9784 ± 0.18016 within

1.4315 ≤ γ ≤ 2.4937

log k

log p(k)

0.0001

0.001

0.01

0.1

1

110100 1000

p(k)

k

SN Computer Science (2021) 2:4

Page 5 of 11 4

SN Computer Science

configuring social network topology. TableS1 (Appendi-

ces) provides the descriptive statistics of network meas-

urements obtained for internal collaborators (n = 2231),

whose attributes data of gender, organization post (posi-

tion), and unit type and region are available (see Sect.2.1

in Methods). For selecting the best network measure-

ments for statistics, it was studied the linear strength of

redundancy or randomness between centralities, modular-

ity and clustering by means of Pearson correlations and

the corresponding statistical significances (TableS2 and

cross-plot Figure S1).

The correlation analysis evidenced strong redun-

dancy between degree k and betweenness (r = 0.8379,

p < 0.0001), and moderate redundancy between k and

closeness (r = 0.2269, p < 0.0001). Furthermore, modular-

ity correlations with network measurements were very low

(0.008 < r < 0.073) indicating randomness. Consequently,

for evaluating differences between grouped attributes, it

was considered only the variables of normalized between-

ness and closeness to assess hub and gatekeeper proper-

ties, respectively, and clustering. Descriptive statistics of

the selected network measurements for each attribute are

shown in Tables S3 to S6.

Table1 shows the p and F statistics obtained with non-

parametric Permutational Multivariate Analyses of Vari-

ance (PerMANOVA) in the Euclidian space to evaluate

differences between the selected attributes. The study was

made with 9999 permutations as a two-way PerMANOVA

for checking any mutual interactions between attributes.

Betweenness centrality has shown not useful to distin-

guish network differences between gender, position, and

unit type and region, suggesting that hubs are relatively

well distributed among groups in the network. On the other

hand, significant network differences were encountered for

closeness centrality (Table1). In particular, the two-way

PerMANOVA tests between gender (p = 0.0229) and posi-

tion (p = 0.0001), and gender (p = 0.0318) and unit type

(p = 0.0479) provided significant statistical interactions

(p = 0.0492 and p = 0.0278, respectively). Nonetheless,

1

10

100

11

01

00

k

nn

(k)

k

Fig. 2 Degree correlation function for the Embrapa coauthor-

ing network (straight line). The statistical regression gives

µ = − 0.09358 ± 0.040969, r

2

= 0.08253, p < 0.026041, and bootstrap

interval of −0.18902 ≤ µ ≤ −0.0032878 with 1999 iterations

Table 1 Two-way

PerMANOVA tests to evaluate

differences of network

properties between attributes:

gender (male, female); position

(controller, researcher, analyst),

unit type (product, thematic,

ecoregion), region (South,

Midwest, North, Southeast,

Northeast)

Significance levels are marked at α = 0.05* and 0.001**

Attribute Betweenness Closeness Clustering

F p F p F p

Gender 0.0586 0.8645 2.8318 0.0229* 0.7483 0.2538

Position 2.1094 0.2392 20.052 0.0001** 19.183 0.0001**

Interaction −406.83 0.4719 −396.37 0.0492* −491.10 0.8186

Region 0.9469 0.2504 0.4405 0.6325 5.2000 0.0001**

Unit type 0.1888 0.9198 2.0815 0.0500* 9.2453 0.0001**

Interaction −97.519 0.5324 −73.007 0.0574 −84.004 0.1536

Gender 0.0874 0.8618 3.9532 0.0357* 1.1785 0.2468

Region 1.3879 0.2039 0.5539 0.6446 6.6307 0.0001**

Interaction −28.973 0.4402 −41.952 0.1438 −57.461 0.1699

Gender 0.1109 0.8489 4.2068 0.0318* 1.2131 0.2397

Unit type 0.3511 0.8550 2.7850 0.0479* 12.135 0.0001**

Interaction 225.86 0.2689 −21.657 0.0278* −86.216 0.2165

Position 1.9267 0.2672 20.088 0.0001** 20.274 0.0001**

Unit type 0.1696 0.9044 1.8781 0.0455* 7.9113 0.0001**

Interaction −233.30 0.4200 −197.03 0.1699 −230.89 0.9716

SN Computer Science (2021) 2:4 4 Page 6 of 11

SN Computer Science

the interaction between gender (p = 0.0357) and region

(p = 0.6446) was not significant (p = 0.1438).

The results suggest that closeness centrality is independ-

ent of the region and somewhat driven by gender (lower

for females) and position (lower for analysts), but unclear

concerning unit type (nonparametric Mann–Whitney and

Kruskal–Wallis tests at Sect.2 of the Appendices). These

findings are corroborated by a contingence table analysis

(Fischer’s exact test) indicating high proportion of females

enrolled as analysts rather than controllers and researchers

(Sect.3 of the Appendices).

Concerning the clustering network variable, significant

differences were detected for position, region and unit type

however without significant interactions (Table1). Differ-

ences in the attribute position are mostly due to lower clus-

tering values for analysts, which reinforces their gatekeeper

role in the network. However, differences in clustering

seems more associated with region and unit type. A paired

Mann–Whitney U test indicated that clustering at the South

region is significantly higher than that measured for Midwest

and North regions. In addition, the same test evidenced that

clustering at product units is significantly higher than that

measured for thematic and ecoregional units (Sect.2 of the

Appendices).

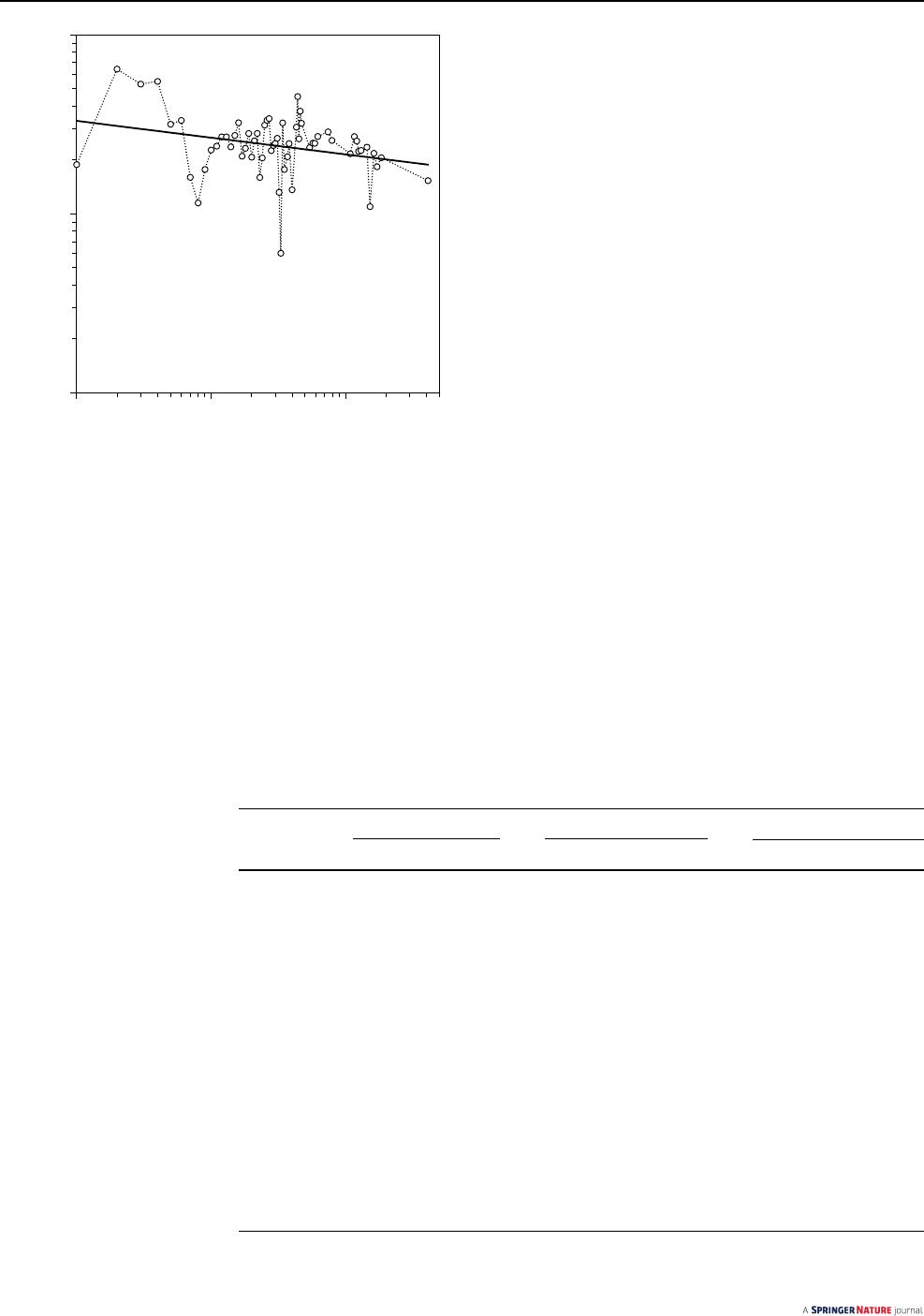

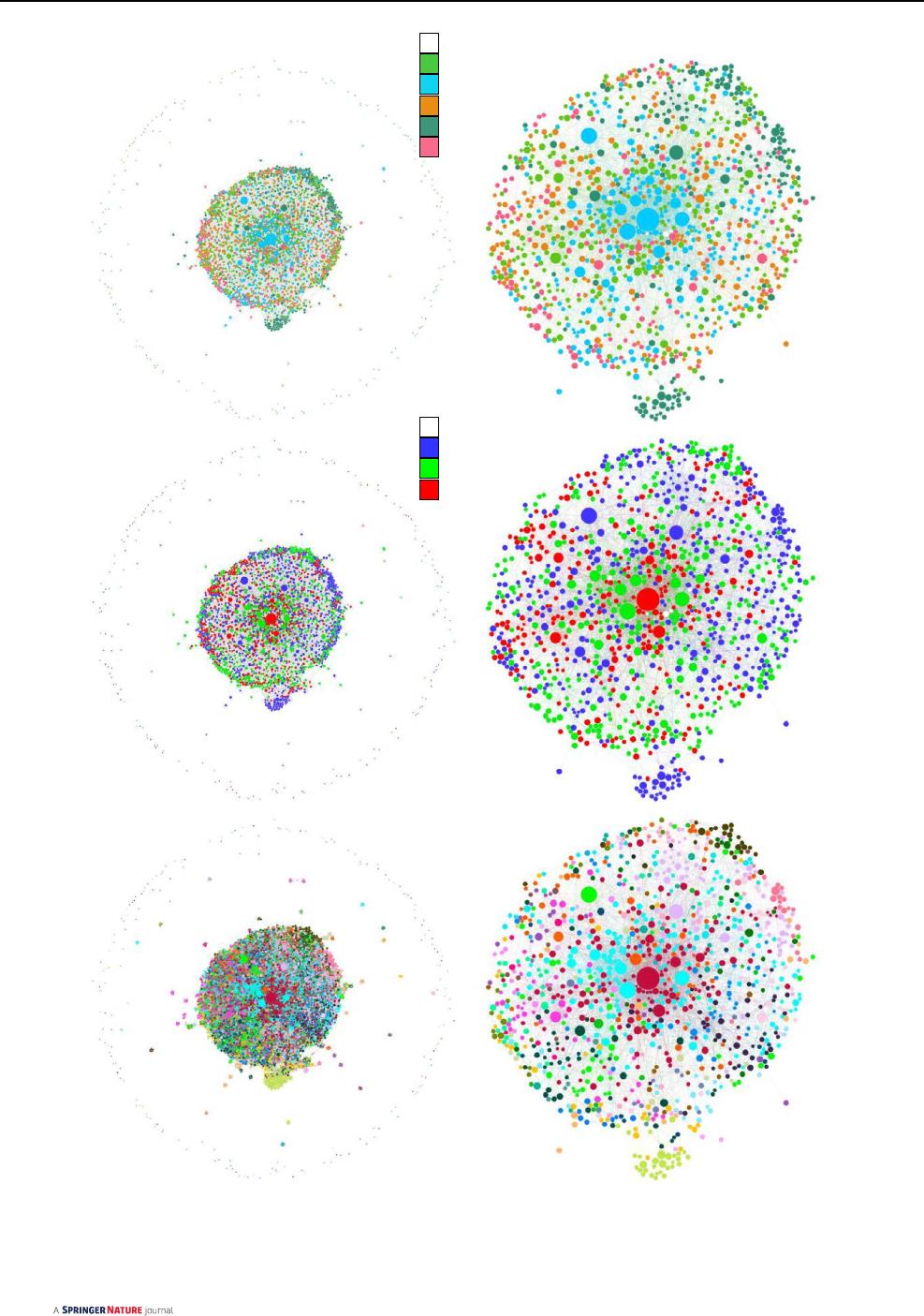

Graph Explorations

Network analysis has identified 206 connected components.

The giant component for which k ≥ 10 has 1107 nodes with

4943 edges. Graph analyses with partitions of attributes by

color are shown in Figs.3 and 4 for the whole network (on

the left) and for the giant component (right sided).

In agreement with the estimated values for γ and µ (see

Sect.3.1), the graphs reveal a radial hub-and-spoke pattern,

in which a constellation belt of low-order nodes surround a

core of internal collaborators permeated by external collabo-

rators (Fig.3a). In the void between the core and the belt,

small components reproduce the hub-and-spoke pattern.

The constellation belt consists of proportions of females

and males (Fig.3b) distributed over regions (Fig.4a), unit

types (Fig.4b), and enrolled as researcher, analyst or con-

troller (Fig.3c).

The core of the giant component gathers mostly research-

ers associated with ecoregional and thematic units (Fig.4b).

The graph suggests a prevalence of males as controllers,

confirmed by contingency tables (Sect.3 in the Appendices).

Statistical differences in clustering by region and unit

type (Table1) are graphically evident in Fig.4a, b. Southern

units gather more nodes in productunits that, as found, tend

to develop more collaboration in clusters. However, hubs

located in thematic and ecoregional units (Fig.4b), in par-

ticular at Midwest (Fig.4a), have greater gravitational force,

sitting in the inner core of the giant component. Modularity

class was somewhat useful for identifying singularities of

communities mutually modulated by region and unit type

effects (Fig.4c).

Discussions andRelated Works

Scale-free networks derive from at least three major ingre-

dients: growth, preferential attachment and fitness [5]. The

present work mostly explores the second factor, in which

high-degree nodes tend to increase links faster than other

low-degree nodes. However, while a network grows over

time, the distinct competitive fitness of nodes may also play

a vital role in configuring hub-and-spoke topologies [5], as

those shown in Figs.3 and 4, which was not addressed here

in details. Therefore, a limitation of this work is that it relies

in a snapshot of the current state of the organization, and an

evolutionary network approach would bring more insightful

information. In any case, deciphering the current topology

of the interdisciplinary Embrapa is the new contribution of

this paper.

Network science applied in the coauthoring system of

Embrapa revealed that the degree of network nodes follows

a power law distribution derived from a scale-free dynamics

with preferential attachment producing a giant component

[9, 39]. For the present case, however, p (k) distribution

does not require exponential cutoffs [10] and the exponent

rests nearly γ ~ 2, a special circumstance associated with the

development of hub-and-spoke patterns over several scales,

in agreement with a disassortative regime [5].

Alternatively, it has been shown that scientific collabora-

tion generally creates an assortative network [13, 33]. Dis-

assortative regimes have been acknowledged as an outcome

of technological and biological networks [13] that embed

some degree of controllability [20]. Therefore, Embrapa’s

scientific co-authorship network resembles networks with

controls and constrains, which agrees with the findings by

Zuo and Zhao [40] that more multidisciplinary institutions

are not necessarily more collaborative.

As the Embrapa coauthoring network evolves, the control

of individual and regional units, combined with competition

and centralized bureaucracy, can synergistically sustain the

observed hub-and-spoke network pattern. Such dynamics

emerges from scale-free networks because connectivity has

considerable effects not only on the behavior of the system,

but also on how the dynamics of the system can be directed

at will, where only a few nodes are needed to control the

entire network, especially when γ ≤ 2 [19].

It has been shown that the size of a minimum dominant

set of a network, Γ, depends on µ, γ, and <k>, but not on

modularity and clustering [19, 20]. Decreases in Γ when

µ ≤ 0 is due to the repulsion (competition) between hubs.

Additionally, Nacher and Akutsu [19] have shown that p (k

Γ

)

SN Computer Science (2021) 2:4

Page 7 of 11 4

SN Computer Science

Int. Collab.

Ext. Collab.

A

C

B

Researcher

Analyst

Ext. Collab.

Controller

Female

Male

Ext. Collab.

Fig. 3 Whole network and the giant component for k ≥ 10 partitioned by internal and external collaborators (a), gender (b) and position (c)

SN Computer Science (2021) 2:4 4 Page 8 of 11

SN Computer Science

A

C

B

Product

Ecoregional

Ext. Collab.

Themac

Southeast

Midwest

Ext. Collab.

South

Northeast

North

Fig. 4 Whole network and giant component for k ≥ 10 partitioned by region (a), unit type (b) and modularity class (c, without legend for 250

classes)

SN Computer Science (2021) 2:4

Page 9 of 11 4

SN Computer Science

does not preferentially aggregate hubs, but decays also as a

power law of k

Γ

, which agrees with 92% of nodes in Γ with

k

Γ

< 20. As a result, the hub-and-spoke pattern guarantees

minimal, but sufficient, network control of the information

flow, limiting the system in the transition between assorta-

tive and disassortative regimes towards the latter. Currently,

the solution γ ~ 2 and µ ≤ 0 found for Embrapa seems driven

by the system self-adaptation to minimize Γ that gathers

about 14% of internal collaborators, principally males (con-

tingence table in Sect.3 of the Appendices).

Scale-free networks lying on γ ~ 2 minimize Γ because

the trivial upper limit of Γ is described by n ~ k

max

, where

k

max

is the highest degree of a network [5]. However, Γ is

minimized for µ < 0 in which hubs are separated and can

independently rule many of low-degree nodes. Alternatively,

low-degree nodes also likely obtain advantages by connect-

ing at least to a single hub [39] for, e.g., paced promotions,

considering the functional stability in the Brazilian public

services.

On the other hand, network control seems useful to focus

on TRL [28] to strengthen collaboration and innovation

with the private sectors [29, 30]. The ability to control the

information flow, however, may bring also implications for

the institutional efforts to boost innovation in open science

based, e.g., on FAIR (findability, accessibility, interoper-

ability, and reuse of digital assets) principles [41]. Conse-

quently, current optimization problems seem associated with

minimal but sufficient organizational changes.

Definitely, more incentives may be necessary to exploit

the potential benefits of multidisciplinary diversity in stim-

ulating more intra-organizational research collaborations

that span disciplinary (and regional) boundaries [40]. For

instance, the current division of Embrapa’s units in three

major types (product, ecoregional and thematic) that favors

competition and isolation could benefit from only one or

two labels aligned to a TRL model—e.g., innovation and

business centers—focused on a few portfolios and mixed or

not with external RD&I associates [26].

An interesting example is the system adopted by the

USDA-ARS, which has physical bases (laboratories) at

universities, working in an integrated manner on specific

research topics [24]. In addition, the programmatic figure of

portfolios is very welcome because it replaces the current

strategy of decentralized units with national missions for

the coordination of large product chains, as well as making

it possible to act on transversal themes in various regions of

the country [27].

In general, organizations have formal and informal

structures. Collaboration is distributed laterally due to

more capacity, transparency and trust, rendered as human

capital [42]. On the other hand, human capital in hierarchi-

cal topologies is asymmetrical and routinely concentrates

between superiors and subordinates [18, 43]. Consequently,

for increasing the pace of innovation, a widespread increase

in human capital ought to be considered throughout the

entire network [42]. Furthermore, an increase in the role

of gatekeeper agents, which is now restricted for analyst

females, may ease the establishment of innovation by bridg-

ing organization’s units.

Lastly, a multidisciplinary organization demanding more

innovation capacity in infodemic societies [3, 4] needs to

seek for new formal and informal rules that optimize degree

and correlation degree distributions toward γ ≥ 2 and µ ≥ 0,

respectively. As communication (network edges) grows, it

seems reasonable to allocate efforts to strengthen the auton-

omy of the nodes [42] instead of increasing the controllabil-

ity of information [44, 45].

Conclusions

The topological study of the scientific collaboration net-

work of Embrapa indicates that nodes degree distribution

is scale free and forms a giant component, whereas nodes

degree correlation suggests a disassortative regime. A hub-

and-spoke topology likely emerges from competition and

minimal but sufficient network control, which may, however,

prevent a required increment in innovation capacity.

Jobs of controller and researcher are twice as many occu-

pied by males, except for the jobs of analysts, who act as

network gatekeepers, as indicated by the measure of close-

ness centrality. Product units show greater affinity to form

clusters than ecoregional or thematic units that, in turn, tend

to concentrate hubs at the inner core of the giant component.

With the largest number of individuals in product units, the

South region tends to develop more collaborative clusters.

Alternatively, hubs located in thematic and ecoregional units

in the Midwest region have greater gravitational force, posi-

tioning themselves at the inner core of the giant component.

Combining the improvement in human capital with the uni-

versalization in the labeling of units can motivate a multi-

disciplinary organization to share knowledge and hasten the

pace of innovation internally and with external associates.

A clear limitation of this work is that it considers only a

snapshot of the current state of scientific collaboration of the

studied organization, and an evolutionary network approach

would bring more insightful information regarding, e.g., the

reasons for reaching the actual topological shape. In any

case, the preliminary deciphering of the current network

topology by network science remains a new contribution,

as, to date, a network study of all of Embrapa’s scientific

collaboration has not been carried out.

Acknowledgements The authors thank to Embrapa for providing open

data that supported this work. The anonymous dataset explored in this

research can be available on request to the corresponding author.

SN Computer Science (2021) 2:4 4 Page 10 of 11

SN Computer Science

Author Contributions Conceptualization: IB; Methodology: IB; For-

mal analysis and investigation: IB; Writing—original draft preparation:

IB; Writing—review and editing: PMS, AHO.

Funding Nothing to declare.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest The authors are members of the studied organiza-

tion, whose motivation is to find new organizational models that im-

prove the capacity for scientific innovation based on ethical and trans-

parency principles to cope with a digital world with increasing spread

of misinformation and denial.

References

1. Strogatz SH. Exploring complex networks. Nature. 2001;410:268–

76. https ://doi.org/10.1038/35065 725.

2. Newman MEJ. Mixing patterns in networks. Phys Rev E.

2003;67:026126. https ://doi.org/10.1103/PhysR evE.67.02612 6.

3. Vosoughi S, Roy D, Aral S. The spread of true and false

news online. Science. 2018;359(6380):1146–51. https ://doi.

org/10.1126/scien ce.aap95 59.

4. Scheufele DA, Krause NM. Science audiences misinformation and

fake news. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2019;116(16):7662–9. https ://doi.

org/10.1073/pnas.18058 71115 .

5. Barabási A-L. Network science. 1st ed. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press; 2016.

6. Watts DJ, Strogatz SH. Collective dynamics of “small-world” net-

works. Nature. 1998;393:440–2. https ://doi.org/10.1038/30918 .

7. Barabási A-L, Albert R. Emergence of scaling in random net-

works. Science. 1999;286:509–12. https ://doi.org/10.1126/scien

ce.286.5439.509.

8. Barabási A-L, Albert R, Jeong H. Mean-field theory for scale-

free random networks. Phys A. 1999;272:173–97. https ://doi.

org/10.1016/S0378 -4371(99)00291 -5.

9. Albert R, Barabási A-L. Statistical mechanics of complex net-

works. Rev Mod Phys. 2002;74:47–97. https ://doi.org/10.1103/

RevMo dPhys .74.47.

10. Newman MEJ. The structure of scientific collaboration networks.

Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2001;98(2):404–9. https ://doi.org/10.1073/

pnas.98.2.404.

11. Aiello W, Chung F, Lu L. A random graph model for massive

graphs. In: STOC ’00 Proceedings of the thirty-second annual

ACM symposium on theory of computing. 2000;171–80. https ://

doi.org/10.1145/33530 5.33532 6

12. Grossman JW, Ion PDF. On a portion of the well-known collabo-

ration graph. Congr Numer. 1995;108:129–31. http://cites eerx.ist.

psu.edu/viewd oc/downl oad?doi=10.1.1.35.4242&rep=rep1&typ

e=pdf.

13. Newman MEJ. Co-authorship networks and patterns of scientific

collaboration. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2004;101(1):5200–5. https ://

doi.org/10.1073/pnas.03075 45100 .

14. Wang Z, Wang N. Knowledge sharing innovation and firm per-

formance. Expert Syst Appl. 2012;39(10):8899–908. https ://doi.

org/10.1016/j.eswa.2012.02.017.

15. Caseiro N, Coelho A. The influence of business intelligence capac-

ity network learning and innovativeness on startups performance.

J Innov Knowl. 2019;4(3):139–45. https ://doi.org/10.1016/j.

jik.2018.03.009.

16. Axtell RL. Zipf distribution of US firm sizes. Science.

2001;293:1818–20. https ://doi.org/10.1126/scien ce.10620 81.

17. Gaffeo E, Gallegati M, Palestrini A. On the size distribu-

tion of firms: additional evidence from the G7 countries.

Phys A. 2003;324(12):117–23. https ://doi.org/10.1016/S0378

-4371(02)01890 -3.

18. Fix B. Energy hierarchy and the origin of inequality. PLoS ONE.

2019;14(4):e0215692. https ://doi.org/10.1371/journ al.pone.02156

92.

19. Nacher JC, Akutsu T. Dominating scale-free networks with

variable scaling exponent: heterogeneous networks are not dif-

ficult to control. New J Phys. 2012;14:073005. https ://doi.

org/10.1088/1367-2630/14/7/07300 5.

20. Takemoto K, Akutsu T. Analysis of the effect of degree correlation

on the size of minimum dominating sets in complex networks.

PLoS ONE. 2016;11(6):e0157868. https ://doi.org/10.1371/journ

al.pone.01578 68.

21. Rodrigues GS, Campanhola C, Kitamura PC. An environmental

impact assessment system for agricultural RD. Environ Impact

Assess Rev. 2003;23:219–44. https ://doi.org/10.1016/S0195

-9255(02)00097 -5.

22. Embrapa. Brazilian Agriculture: one of the most efficient and sus-

tainable in tropical zones. 2017. http://ainfo .cnpti a.embra pa.br/

digit al/bitst ream/item/16481 5/1/38137 -folde r-suste ntabi lidad

e.pdf. Accessed 15 Oct 2020.

23. Salnikova E, Grunert KG. The role of consumption orientation

in consumer food preferences in emerging markets. J Bus Res.

2020;112:147–59. https ://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusr es.2020.03.006.

24. Freitas-Filho A, Paez MLDA, Goedert WJ. Strategic planning in

public R&D organizations for agribusiness: Brazil and the United

States of America. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 2002;69(8):833–

47. https ://doi.org/10.1016/S0040 -1625(01)00139 -1.

25. Figueiredo PN. New challenges for public research organisations

in agricultural innovation in developing economies: evidence

from Embrapa in Brazil’s soybean industry. Q Rev Econ Financ.

2016;62:21–32. https ://doi.org/10.1016/j.qref.2016.07.011.

26. Alves AA, Hoffmann A, Nepomuceno AL, Oster AH, Fonseca

CEF, Torres CRB etal. Task force to support structural and func-

tional improvement of Embrapa’s Decentralized Units. In: Internal

Executive Report. Embrapa Brasília-DF. 2018. p. 28.

27. Bittencourt DMC, Campos MM, Euclides-Filho K, Moretti C.

Análise de redes sociais como ferramenta para a gestão da pes-

quisa e desenvolvimento (PD) na Embrapa. In: Desafíos y opor-

tunidades de las Ciencias de la Información y la Documentación

en la era digital: actas del VII Encuentro Ibérico EDICIC 2015

(Madrid 16–17 November 2015). Universidad Complutense de

Madrid, Madrid. https ://eprin ts.ucm.es/34645 /1/293-Matia s_redes

-socia is.pdf.

28. Mankins J. Technology readiness assessments: a retrospec-

tive. Acta Astronaut. 2009;65(9–10):1216–23. https ://doi.

org/10.1016/j.actaa stro.2009.03.058.

29. Capdeville G, Alves AA, Brasil BSAF. Modelo de Inovação e

Negócios da Embrapa Agroenergia: Gestão Estratégica Integrada

de P&D e TT. Documentos 24 Embrapa Brasília-DF, 2017. p.

45. https ://www.embra pa.br/busca -de-publi cacoe s/-/publi cacao

/10853 22/model o-de-inova cao-e-negoc ios-da-embra pa-ag roe

nergi a-gesta o-estra tegic a-integ rada-de-pd-e-tt. Accessed 16 Oct

2020.

30. Embrapa. SEG—Embrapa Management System: manual on the

use of the TRL/MRL scale. 2018. https ://cloud .cnpgc .embra pa.br/

nap/files /2018/08/Escal aTRL-MRL-17Abr 2018.pdf. Accessed 16

Oct 2020.

31. Golbeck J. Analyzing the social web. 1st ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier;

2013.

32. Marsden PV. Measures of network centrality. Int Encycl Soc

Behav Sci. 2015;16:532–9. https ://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-

09708 6-8.43115 -6.